Janina Bąbka Iwanica

Poles meeting for the first time in New Zealand tend to want to know by what means one

arrived. One of the inevitable first questions, whether one is attached to “Pahiatua,” is understandable when one

considers how warmly New Zealanders received the 838 Polish refugees in November 1944.

Janina Bąbka Iwanica is one of the many Polish New Zealanders who arrived here by different means.

Pani Janina comes from western Poland, occupied by Germans after Hitler invaded on 1 September 1939. In June 1941 those

occupiers transported her and her parents to Germany, where she experienced the end of the war in Europe. She arrived in New

Zealand, not as an invited refugee like the Pahiatua group, but as a displaced person under the auspices of the International

Refugee Organisation (IRO).

I met Pani Janina in February 2013. She was one of the first people I interviewed for this website. I remain grateful for her

calm and gentle patience.

My appreciation and best wishes to Pani Janina.

—Basia Scrivens

January 2015

THE DETERMINED CHORISTER

by Barbara Scrivens

Janina Bąbka Iwanica discovered the joy of singing in a choir at a Displaced Person’s camp in post-war Germany. Mingling her voice with others still gives her pleasure and comfort.

Being part of a choir became one of the constants in Janina’s teenaged life as she moved with her parents from one DP camp to another. Friendships and immediate surroundings were often fleeting but she could trust the songs she learnt not to change.

Change had no part in Janina’s early life in Łysaków on the Pilica river’s upper reaches. Cousins and friends occupied no more than 14 farmhouses in the tiny settlement, then in south-west Poland, and had few secrets.

An only child, Janina started school in 1938. Every morning she walked about two kilometres north along the sandy river to neighbouring Kuźnica Wąsowska for general schooling. Every afternoon she had a further five-kilometre walk, through the woods in the opposite direction, for religious instruction in Przyłęk, a larger village with a church. The closest town, Koniecpol, lay about halfway between Częstochowa and Kielce.

After several generations, those who stayed on the farms had less and less land from which to make a living.

Janina, named after her paternal grandfather, was born in the family farmhouse in 1931, as was her father, Filip, in 1897. Her paternal grandmother was Joanna, neé Kucharska.

Janina’s mother, Józefa, and maternal grandparents Franciszek and Franciszka Sczlacheta came from Kuczków, a village beyond the woods.

The small sizes of the individual farms in Łysaków evolved naturally, the result of a Polish tradition to divide family land equally between children. After several generations, those who stayed on the farms had less and less land from which to make a living. If a child wanted to earn an income elsewhere, the usual agreement was that he or she would sell off his or her land to the siblings left behind. Janina’s father was one of six children and when Jan Bąbka died, each of his children received two acres (morgi). Janina remembers an uncle moved away to Kalisz, near Silesia, where he made a life for himself as a shopkeeper.

_______________

The Pilica ran low in the hot summers. Farther north, it became a substantial tributary of the Wisła (Vistula) but in Łysaków it was more of a meandering stream, a magnet for children. Janina remembers looking through the clear water and seeing fish moving along the sandy bottom. In summer, the villagers dug out peat turf from the swampy land towards Przyłęk, dried it, and stored it for fuel. Moss and sludge covered the water that seeped into the remaining holes.

“It became a thick carpet and we used to jump on it. We could have drowned, but we didn’t think of that.”

The frivolity of flowers had no place in the Bąbka garden. Janina’s father grew wheat and corn in the fields and vegetables closer to the house.

One of Janina's jobs was taking the three family cows to their pasture nearby.

“All the other children in the village had to do the same thing but I was the youngest and I was pushed into doing all the running around, making sure the cows didn’t eat what they shouldn’t.”

Or go where they shouldn’t. A cow would sometimes venture into the swamp and become so stuck that it took half the village to free it.

“Cranberries grew in those swamps on vines creeping along the ground. The fruit was big but sour. Sometimes we ate them but we didn’t like them very much. The paddocks were filled with flowers in the summer.

“We used to cross the river and go blueberry picking. Usually we ate them but sometimes we had enough to sell at the market. There were huge blackberries that grew on the hill on the side of the swamp where we used to look after the cows—lovely, sweet and juicy blackberries. We called them ‘dziady.’

“One day, we had been blueberry picking and I wanted to wash off the sand from my feet. Before I knew it, the river began to carry me away. I remember hearing, ‘She’s drowning!’ and someone grabbed me and pulled me out.”

The frivolity of flowers had no place in the Bąbka garden. Janina’s father grew wheat and corn in the fields and vegetables closer to the house.

“He grew tomatoes, cucumbers and onions but his carrots never did very well. I used to pull them out, eat the big ones and put the little ones back thinking they would grow bigger. My father couldn’t understand what was wrong with his carrots. Years later, I confessed and he just laughed.”

“The priest came and gave him the last rites and my grandmother hugged me. She’d never hugged me before.”

Janina and her parents lived on one side of the farmhouse. One room served as a bedroom, kitchen, dining and living room. They had a well for water, an outhouse, storage buildings for corn and hay and a stable for their cow.

Joanna Bąbka lived on the other side of the house with a daughter, another son and a daughter-in-law. The garden’s plums, pears and apple trees belonged to her, as did two cows in a separate stable.

Janina remembers her mother baking bread, and loving the smell. Her mother made a fire in a container that heated the oven bricks. Once the bricks were hot, she shovelled out the ash and put in the bread dough to bake.

A highlight in the freezing winter was the traditional wigilia (Christmas Eve dinner), celebrated by the Bąbka family with a white tablecloth and a cushion on which hay was laid to represent the stable in Bethlehem, and on top of that, an opłatek, a special Christmas wafer symbolising peace and unity. Poles have been sharing opłatki before wigila for centuries. The father usually makes the first break of the opłatek and starts sharing it. The rest of those around the table take turns to break off a piece of one another’s opłatek, wish one another well and forgive any slights that may have occurred during the previous year.

Janina’s favourite Christmas treat was the rice pudding her mother made to accompany the compote for dessert, a tradition she carried on for her own children. In Łysaków Józefa Bąbka went to Midnight Mass and back to church again with the whole family on Christmas Day.

The Bąbka’s simple but settled life changed for the first time when her father became seriously ill.

“The priest came and gave him the last rites and my grandmother hugged me. She’d never hugged me before. It was the first time. My father nearly died, but the next morning his brother took him to Koniecpol to a doctor who told him not to use any salt or fats but to eat soft-boiled eggs, milk without fat, and gave him some pills. My mother couldn’t manage the farm on her own and I couldn’t go to school.”

With the family only just eking out a living from their strip of land, and her father’s medical expenses, helping her mother run the farm took priority over replacing well-worn school shoes and schooling.

Filip Bąbka recovered and by the time World War 2 arrived, Janina was again walking to classes.

_______________

“They wrote everything down… they decided how much they wanted, so many eggs, so much grain… It was more than we ever got from our farm.”

“I remember the war. People were running from the towns to the country. We had no shops but the Germans emptied those in the towns and people seemed to think they could buy food from the farms. The village was crowded with people but there was no sanitation for them and the flies were everywhere.

“The town people thought they were safer in the villages but I remember the German planes flying over the forest and shooting into it with machine guns because they expected people were hiding there.”

Under German occupation, the productive farms in Poland faced increasing pressure to hand over their crops and animals. Janina remembers German officials and soldiers arriving at their farm and taking an inventory.

“They wrote everything down, how many chickens you have, how many pigs you have, how many cows you have, what vegetables… things like that. Then they decided how much they wanted, so many eggs, so much grain… It was more than we ever got from our farm. They also documented all the people. They knew who lived where. When we had no more to give, we had notification we had to go to Germany.”

The German order to vacate their farm came in June 1941, the month when Hitler extended his immediate European military efforts and invaded first, his former ally Stalin’s occupied territory in eastern Poland, then Russia itself. Hitler’s war effort had used up most able-bodied Germans and Germany’s farms needed labour. Polish farmers and their families became useful.

There may have been goodbyes but Janina does not remember any. Packing, too, was simple—there was not much to take.

Janina believes her family was the only one taken from their particular village because the German tally of residents did not generate many candidates.

The village elder made sure everyone knew when the Germans were due to arrive. Young people had time to hide and the German officials faced mainly older inhabitants. Most of the young men in the area had already joined the Polish underground resistance units, the Armja Krajowa (Home Army or AK).

Janina suspects another reason for her family’s deportation to Germany could have been her father’s subscription to the weekly newsletter of the zielony sztandar (Green Banner), a joint publication of three left-wing political parties, the Polish Peasant Party (PSL Piast) the Polish Peasant’s Liberation Party (PSL) and the Peasant Party (SCh).

There may have been goodbyes but Janina does not remember any. Packing, too, was simple—there was not much to take. All their belongings, mostly clothes, took little space.

“I know my father gave our table and chairs to the neighbour to use until we got back.”

That neighbour took Filip, Józefa and Janina in his wagon to the railway station in Włoszczowa, where they caught a train to Częstochowa.

_______________

And so started Janina’s decade of forced nomadic life.

Janina remembers spending one of the first nights away from home in a school hall among many other Poles sitting and sleeping on the ground.

“A man gave my father a bread coupon… but the shopkeeper looked at him and called the police because he wasn’t allowed to have bread coupons.”

“The next thing I remember is being on the train to Germany.”

At their destination, Ahlen, nearly 1,000 kilometres west of Łysaków, German farmers waited to receive their allocation of new labourers. The Bąbka family went with one called Kleinknopf.

“I remember walking through the streets of Ahlen. People were watching us from the windows and were throwing things for us. A man gave my father a bread coupon so he could buy some bread. My father asked the farmer if he could go to the shop. The farmer let him but the shopkeeper looked at him and called the police because he wasn’t allowed to have bread coupons. The farmer explained to the policeman where my father had got it and they let him go—without the bread or the coupon.

“I was 10 years old. I had to work with my parents. First, I was a kitchen maid, cleaning windows, cleaning floors, cleaning shoes, helping in the garden and when I got sick, I wasn’t given food. The farmer’s wife said ‘Keine arbeit, kein essen’ (no work, no food). It wasn’t that bad, we were fed all right and my parents shared their portions with me.

“It was funny later but I had a boil right in my buttock and I couldn’t work because I couldn’t walk. It was so painful and still, the farmer’s wife had to see it to make sure I was really sick.

“The farmers were all right. They were Catholic. One Sunday a month there was a Mass for Polish people in a church in Herzveld. They made sure we went to church. Not with them—it was a special Mass for the Poles even though the priest was German and Mass was in German.

“I didn’t have First Holy Communion in Poland because we had to leave. I had done my religious studies and my mother went to our parish priest in Przyłęk and asked if I could have my First Holy Communion in Poland because I was going away. He said, ‘No.’

“My mother couldn’t understand why he wouldn’t help me but there was nothing she could do because soon we were gone. When we were sitting in church again in Germany just before communion she looked at my father and he looked at her… Should they let me go?… and they nodded to me and I went and that was my First Holy Communion.

“After a while we were relocated. The farmer wanted more than one working person and my mother was always sickly. She had emphysema and I was just a child. We went to a neighbour, Kristofer Kampf.

Janina and her parents outside German farmer Kristofer Kampf’s farmhouse.

“We were there for a while but it was the same story. I was a child. I had to work a bit in the kitchen a bit in the field, you know how children are: I had to chop kindling for the fire and the farmer could see me through the window. I was sitting and playing around, and chopping a little bit and playing around, chopping some more, playing some more…”

At Kampf’s farm, Filip found out that Germans arrested his brother in Kalisz and transported him to Auschwitz, the concentration camp the Nazis created in the Polish town of Oświęcim. An ethnic German neighbour had reported him for receiving the zielony sztandar. The brother’s shop became the informant’s reward. The brother’s wife and daughter became the informant’s employees. The wife and daughter, unable to confirm that Nazis moved him to Bergen Belsen in Germany, never saw him again and accepted he died there.

“My father was so upset that his brother had been taken, he wanted to go and help him. The farmer Kampf calmed him down and said if he went, he would end up the same way. Later, my uncle’s wife wanted to get his body, but someone told her there would only be ashes and those would not be his.”

The Bąbka family moved to the Wűster farm, but the pattern remained: Their joint labour did not meet the farmer’s needs.

“Afterwards we went to the Haya Boenstein farm, a huge ranch near the town of Beckum in Westfalen. I had to work in the kitchen. My parents received provisions and had to cook for themselves. It was different because at the other farms, the farmer’s wife cooked and they fed us. At Haya Boenstein, there were many more workers. The farmer and his wife ate alone. The German foreman and his wife, the housekeeper and two German servant girls ate together. The farm workers, including two Poles and a Russian, ate in a separate dining room. The ones who were married had their own rooms and cooked for themselves.

Janina knew of no bomb shelters in the area so suspects that the bell-ringing warned rather than instructed.

“I ate on my own in the kitchen. I lived on my own in the big house in a little room in the attic and my parents were living on the farm. I was allowed to see them for an hour in the evenings but if I was late back from visiting, I wasn’t allowed to see them the next day. I had to go to the sitting room and say good night to the housekeeper when I came in.

“One day it was so dark, I was disorientated and I couldn’t find my way back. There was an alarm for when the English planes came at night. One of the girls, Bernadina, was ringing the bell to let us know the bombers were coming and we had to take shelter.

“I was yelling, ‘Bernadina, Bernadina’ but she couldn’t hear me and I couldn’t see her, so I was late coming in. The next day, I wasn’t allowed to go and see my parents.”

Janina knew of no bomb shelters in the area so suspects that the bell-ringing warned rather than instructed. Soon after that incident, it became clear that the war in Europe had ended.

“There were two main roads alongside the farm. For a week, day and night, military trucks and tanks streamed past. The Americans came first—we knew from the flags and everybody called them ‘Yanks’ and ‘Okays.’ The British came later.

“My father found out there was a camp for foreigners and decided we should go there. The farmer didn’t like it but he couldn’t do anything about it. He had to let us go.”

_______________

The family’s status changed from forced labourers to displaced persons. Their four farm placements in four years turned into more frequent moves from one DP camp to another in Germany.

The Bad Waldliesbon DP camp became their first stop, then Paderborn, then Haltern. Filip stayed behind in hospital in Schusterkrug, near Kiel in northern northern Germany, while Janina and Józefa moved to Rendsburg.

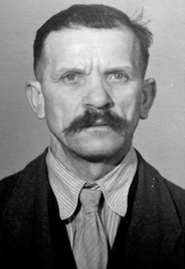

Janina treasures these identity photographs of Filip and Józefa taken by DP camp

officials.

Left, Haltern in 1947.

“We were moved from place to place. We had no say. Sometimes we spent only months in a camp. We were just Poles. They kept the nationalities together. Usually, we stayed in big rooms shared by two or three families. There were some very quick friendships and goodbyes although I did make some long-lasting friends I carried on writing to, like my son’s godmother who lived in New Jersey in America.”

“The first time I tasted chocolate was when we got a Red Cross parcel after the war. It came from the UNRRA [United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration]. It was unexpected and delicious!”

Attending school and activities such as Girl Guides eased the tedium of camp life for Janina.

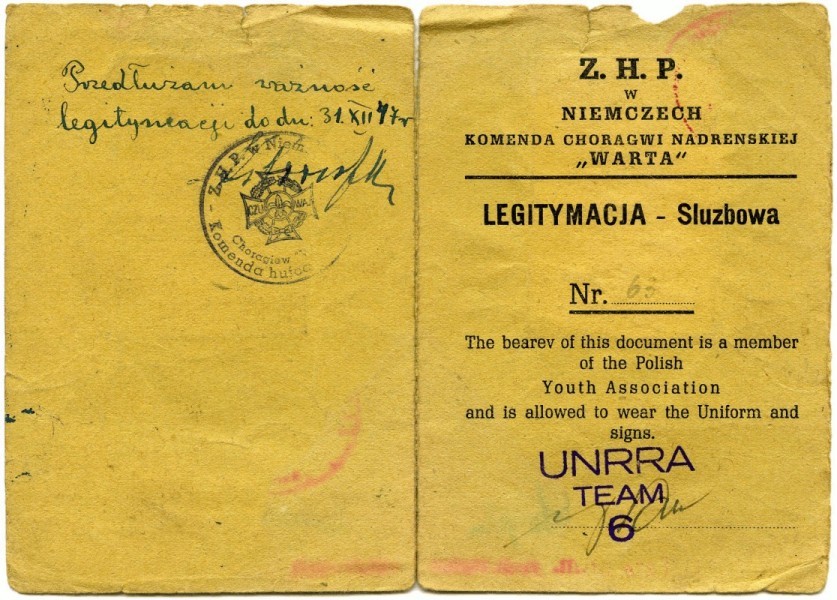

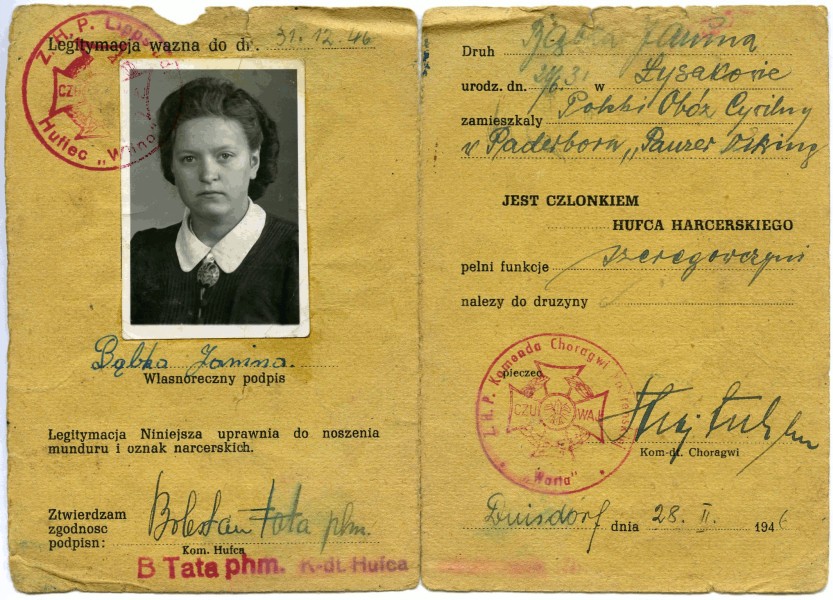

The front and inner pages of Janina’s official membership of the Polish Scouting Association operating in the DP camps. The date stamp shows 28 February 1946.

Janina continued her membership in Haltern and went to a scouting jamboree in Cologne in 1947.

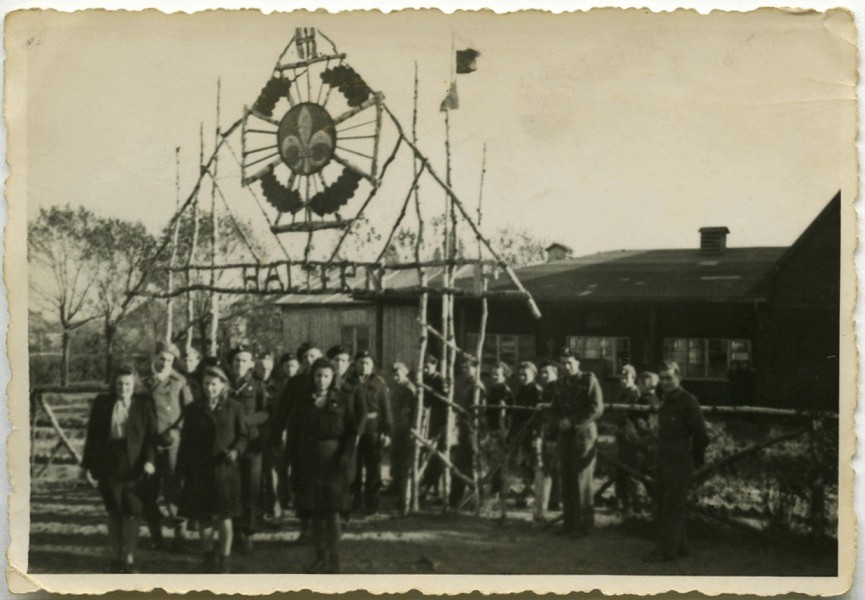

“It was lovely, meeting the Polish groups from the other camps.” That jamboree coincided with the Sixth World Scout Jamboree, held in Moisson, France.

Janina is in the middle at the back, with others in the Haltern scout group.

The Haltern scout group's entrance banner at the Cologne jamboree.

The Haltern camp also had a theatrical group and Janina remembers travelling to other camps, performing plays for occasions such as Easter.

The Paddeborn and Haltern camps supplemented Janina’s year of Polish schooling. She finished six years’ studies in three and by the time she finished a nursing course in Hamborn, her parents had moved to Schusterkrug.

Janina estimates that Haltern housed more than 10,000 displaced persons. UNRRA authorities relocated Haltern’s German residents after the war to make way for the new temporary inhabitants, mostly Poles, three to four families sharing each house.

“I loved to learn Polish and nature study. I struggled with maths and remembering dates in history. In my sixth form the headmaster took me aside every day and gave me extra lessons. He made sure I passed all my subjects.

“I spoke German better than Polish because I got books in German, like the translation of in desert and wilderness by Henryk Sienkiewicz. When I came here [New Zealand], it was easy for me to learn English because I knew German and so many words are similar or the same—bread, Brot; butter, Butter.”

The church choir became another of Janina’s pleasures. She first joined one run by the parish priest in Rendsburg and here is fourth from the lefth.

A New Years’ Eve dance in Schusterkrug provided the setting where Janina met her first husband, Kazimierz (Kazik) Iwanica, visiting friends at the camp. He had spent the latter part of the war working in a brick factory in Germany.

It pleased Janina that her father got on well with Kazik because shortly afterwards, Filip Bąbka died from complications after surgery for an inflamed duodenum. The Schusterkrug hospital told Janina that Filip’s sudden death had been preventable but he received incorrect treatment at the DP camp’s medical unit, which had no qualified doctors. Despite Janina’s imploring the attendants to send her father to a “real” hospital, they acted too late.

Two days after the DP camp agreed to move her father, Janina and Kazik went to the hospital to visit him. Instead of being able to see Filip as they expected, they received the words “Leider, nicht mehr.” (“Sorry, no more.”)

“I asked what happened and they said he died after the operation. The doctor said if he was taken to the hospital two weeks earlier he would have had a long life ahead of him but…

“When I went back my mum saw my face and said, ‘Oh my God, what happened?’ She said it was my fault but I don’t think she believed that.”

At 17 Janina saw her father buried in the Rendsburg cemetery.

By then Janina and Kazik had fallen in love and New Zealand had accepted Kazik as an immigrant. Janina and her mother decided they would follow him and moved to an immigration transit camp in Fallingbostel.

Janina remembers a Mr Pearce, who she believed was the New Zealand consul for Germany.

“He promised us that we would be accepted by New Zealand and eight months later, I got an invitation to come. I wish I had kept that letter.”

One of Janina’s regrets is not being able to thank him for what he did for her.

“I didn’t have the English and I didn’t know how.”

_______________

Janina could not leave with Kazik. She and Józefa still had to appear on an immigration list. Józefa Bąbka, again ill with emphysema and Tadeusz, Janina and Kazik’s baby son, who authorities deemed too young to travel, complicated matters. Before he left, Kazik transferred to the CMWS (Civil Mixed Watchman’s Services) in Hamburg to be closer to his family. With 379 other Poles he boarded the ss hellenic prince in Tirpitz on 8 August 1950 and, via Bremerhaven, arrived in Wellington on 18 October.

Meanwhile, the IRO approached other countries to take in Janina, her mother and Tadeusz.

The IRO photograph used to attract sponsors from Australia and America.

Janina recalls two vivid dreams that kept her positive: The first occurred the night before one of Kazik’s weekend visits.

“In my dream, we were together at a crossroads and he was saying, ‘You go this way and I’ll go that way and we’ll meet over there.’ It did work out exactly like that, although there were times before it happened when I was wondering whether we’d ever be together in New Zealand.

“The second dream was of a man at the top of a hill. He grabbed my arm and threw me to the other side. I know that man was Mr Pearce. I am so grateful to him.”

After Kazik left, Janina, Józefa and baby Tadeusz spent another year moving three more times—from Fallingbostel back to Pinneburg, then to Lubeck for more screening, and finally to Bremerhaven to wait for the ms scaubryn. That ship took them as far as Melbourne where they stayed at the Bonegilla Migrant Reception and Training Centre, north-east of the city. They travelled by train to Sydney and arrived by flying boat in Evans Bay, Wellington, on Labour Weekend Saturday. Janina, her mother and Tadeusz appear on a list of refugees accepted under the IRO resettlement scheme, as part of a series of nominated drafts between January 1951 and April 1952. Kazik sponsored them.

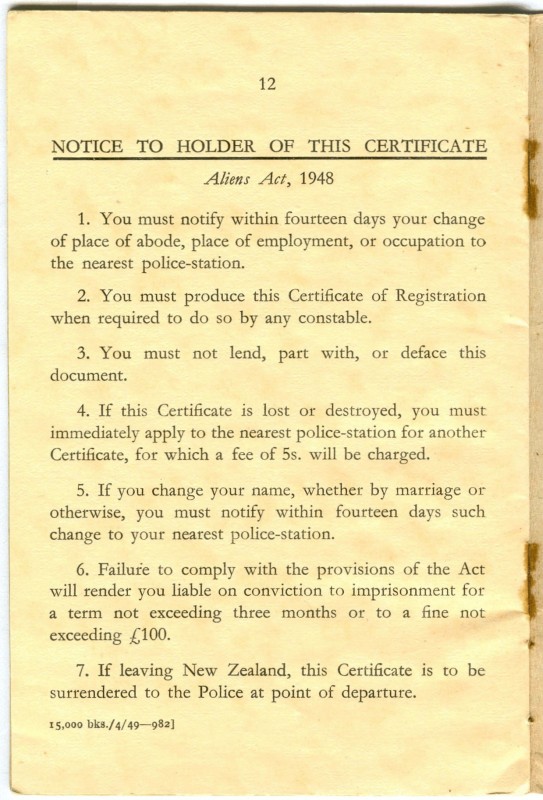

On arrival, they went straight to the flat he had found. Two weeks later, Wellington’s District Police Aliens Officer issued them with the khaki-coloured Certificate of Registration booklets, known as alien passports, which non-New Zealanders had to carry under the Aliens Act of 1948. The first stamp in Janina and Józefa’s was dated 21 November 1951.

An interpreter explained the Alien Act rules on the inside back page:

- 1. You must notify within fourteen days your change of place of abode, place of employment, or occupation to the nearest police station.

- 2. You must produce this Certificate of registration when required to do so by any constable.

- 3. You must not lend, part with, or deface this document.

- 4. If this Certificate is lost or destroyed, you must immediately apply to the nearest police-station for another certificate, for which a fee of 5s. will be charged.

- 5. If you change your name, whether by marriage of otherwise, you must notify within fourteen days such change to your nearest police-station.

- 6. Failure to comply with the provisions of the Act will render you liable on conviction to imprisonment for a term not exceeding three months or to a fine not exceeding £100.

- 7. If leaving New Zealand, this Certificate is to be surrendered to the Police at point of departure.

The act interpreted an alien as “a person who is not a British subject, a British protected person, an Irish citizen or a Western Samoan.” It required all aliens older than 16 to register with the police on arrival in New Zealand.

The Citizenship Act repealed the Aliens Act in 1977 and ended the official use of the term ‘to naturalise.’

The Alien Act’s authoritarian rules did not bother Janina, relieved to be able to stay in New Zealand with her husband, child and mother.

“We were so used to being pushed around and having to carry identity cards that it didn’t bother us.”

Janina never told her mother of the card’s prescriptive details and Józefa lived in happy incomprehension with the family until she died in June 1962.

“We came here and it was so good for us. We had a double bed to sleep in, a room to ourselves, and a kitchen. There was no sharing with other families. After the refugee camps it was heaven.”

The family lived in Salisbury Garden Court in Wadestown, Wellington. Tadeusz acquired two brothers, Edward and Ryszard and a sister, Zofia. As their family grew they looked for a larger house. Rental housing in 1950s Wellington was scarce and the Iwanicas paid £100 “key money” to secure their tenure in the same complex.

“We had to borrow some of it. We didn’t know that we could have put a deposit on a house for that kind of money.”

Janina, Kazik and Tadeusz received New Zealand citizenship in December 1959.

A 1967 photograph of the Iwanica family. In the back from left to right are Tadeusz, Kazik and Edward. In the front are Zofia, Ryszard and Janina.

_______________

Janina returned to Łysaków in 1975. The village she knew was almost derelict. (It no longer features on modern maps although there is another Łysaków near Mielec.)

Familiar buildings stood among overgrown weeds. Janina recognised the huge hazelnut bush of her childhood and hugged it. The crystal water of the Pilica had disappeared, the river so polluted that she could not see the bottom. Dirty grey sediment replaced the sand she remembered. An uncle and his wife still lived in the old Bąbka farmhouse, the only relatives left.

Her father’s youngest sister moved to Silesia and another aunt who survived the war moved to Lubin, also in Silesia. Janina still corresponds with a cousin, also born in Łysaków. They met in Legnica, where he now lives. Janina’s paternal grandmother survived the war in Łysaków and lived to 90.

_______________

Janina again took solace in singing after Kazik died in 1991.

She joined the Choir Polonez, started by Wellington’s Polish Association and run by Malena Lawenowska, a Gdańsk Music Academy graduate. The choir gave 150 concerts in its 10-year existence, including at the opening of Wellington’s Te Papa Museum in 1998. Janina loved her experience at the 1994 Pole Art festival in Adelaide, and performing with members in Melbourne. The choir presented its farewell concert at its birthplace—the Dom Polski in Newtown, in May 1999.

Janina still sings with the Polish church choir in Avalon, Lower Hutt.

The Wellington Choir Polonez at the Adelaide Pole Art festival in 1994.

It still bothers her that she has been unable to find the elusive Mr Pearce, despite combing through as many of her immigration records as she can find. She regrets losing the letter inviting her to New Zealand in 1951.

“With all the screenings and interviews we went through, I did think that there would be something [official] but there is nothing relating to us with the IRO.”

Janina wonders whether Mr Pearce knew how grateful she was for the gift he bestowed on her in Germany so many years ago.

She continues to believe that one day she will find him, or someone from his family. She still wants to say the “thank you” she was unable to as a young woman.

© Barbara Scrivens, 2014.

Updated September 2017

APART FROM THE FIRST ONE, ALL PHOTOGRAPHS AND DOCUMENTS IN THIS STORY ARE FROM THE IWANICA COLLECTION.