VISITING POLAND UNDER MARTIAL LAW

by Michael Jarka

I was in my teens before I realised people around us came from different places.

We only knew we were Polish because of the ‘funny’ surname and my dad spoke Polish. It never occurred to me he had a ‘different’ accent.

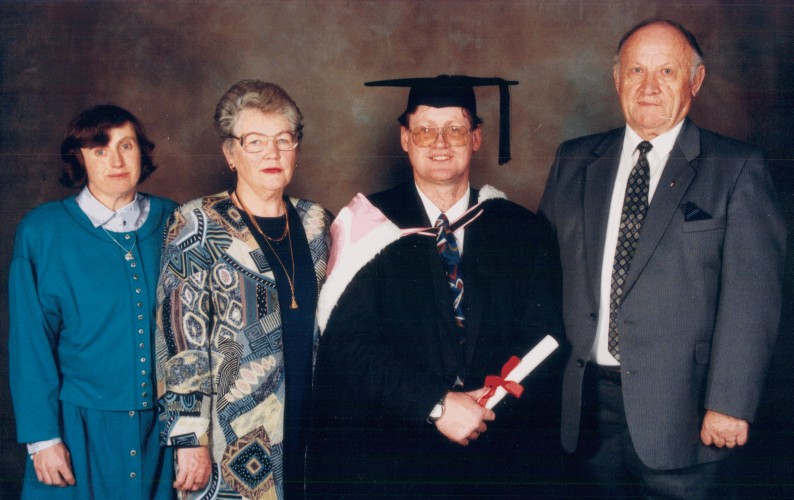

My mother, Stella, was a fourth-generation New Zealander. I never compared Dad’s accent to Mum’s. He just spoke differently, as did the parents of our Dutch neighbours. We kids all played together and spoke the same. I don’t remember my two younger sisters or I ever singled out or treated differently because we had a different surname. Although I was called Michael and my younger sister, Elizabeth, Rozalia, the first-born daughter [on the right above], was named after our Polish grandmother.

The first time I met other Polish people was when I went to high school and there were three other boys from Polish families in my Form 1 class—Pąk, Fajner and Mydłowski. It transpired that Dad knew the families.

When I was in my teens, I helped with the building of the Polish Club in Morningside, Auckland. I used to do Polish dancing there into my early twenties, which I enjoyed immensely. I also celebrated my 40th birthday and later my wedding reception there.

It was while I was on my OE [Overseas Experience] in the UK in 1984 that I became determined to visit Poland as a tourist.

I was curious to know more about my father’s Polish heritage and I wanted to see the country.

A typical 1980s street, this one in one of the older parts of Białystok.

I had grown up listening to stories about his Polish heritage and customs, but Dad didn’t talk much about his horrific experiences once the war started and the Soviets removed him from his home in Białystok and took him to Khazakstan.

I knew he had been through it because when I was in my twenties, we had a thriving Polish youth group in Auckland and people talked. We also did sports exchanges with the Wellington Polish group and I listened to their stories.

I heard about the deportation trains and my ears immediately pricked up because trains had become a special interest for me. At that stage, I did not know that the trains my dad spoke of were not the usual passenger transports. Only later in his life, Dad started talking about how when he was in school they’d hear shooting and realise it was possibly people being executed and I heard about some of the horror he had gone through.

Dad kept those aspects of his past from us deliberately because he didn’t want his children to be upset by his devastating experiences. Dad wanted my siblings and me to grow up with the innocence and joyful childhood he never had. One of his friends did talk openly about what happened because he wanted his kids to know. I overheard him:

“You kids don’t know how lucky know are…” and “The freedom we fought for…”

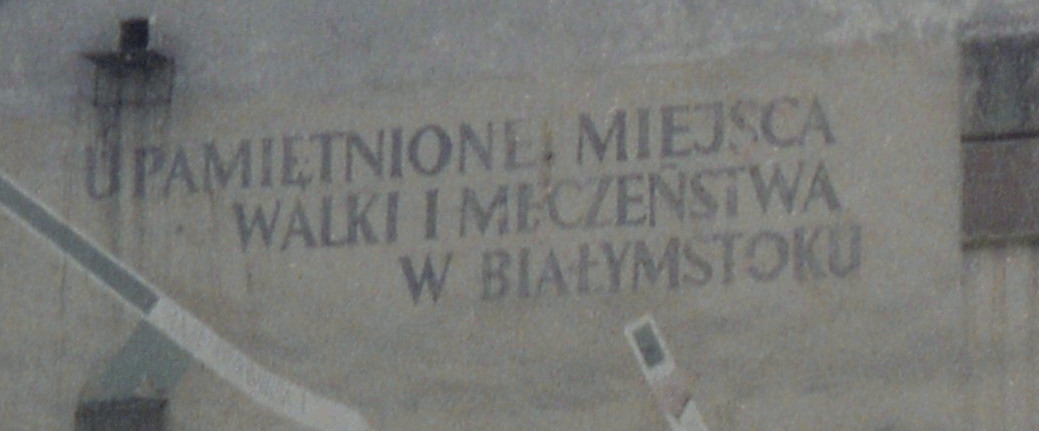

Michael found this freedom of expression on a side wall of an apartment block in Białystok. The statement “Upamiętnione. Miejsca walki i meczeństwa w Białymstoku” above the map and raised site-markers translates as “Commemorated. Sites of struggle and martyrdom in Białystok.”

Michael noticed this building in Warsaw's Old Town (Stare Miasto). The lion and dragon on the facade, and the celestial artwork and detailing under the window sills, keep a modest distance from the obvious neglect of the lower storey. It seems to have survived the bombing of World War Two—or did it? Bombing by Nazis destroyed the Old Town and Warsaw residents later rebuilt the area under the guidance of the Warsaw Reconstruction Office. UNESCO added the Old Town to its list of world heritage sites in 1980. This is known as John's house, rebuilt like others according to a painting by 18th century Italian artist Bernardo Bellotto rather than its actual state before the war.1

The same building in 2016. The sub-standard materials used to rebuild the bombed area in

post-war communist-controlled Poland are being replaced, and the buildings brightened.

A close-up of the gilded lion on the first-storey corner of John's house.

Dad was very determined that we should never be deprived nor suffer materially in the same way that he and other refugees did. He just shut it out, but there was always something in the throat when he talked about his family. He’d talk around what happened, not about what happened.

When I visited Poland in 1984, it was a Soviet socialist state under martial law. At that stage, none of us knew that we had living relatives in Poland. We had had no contact with anyone in Poland since my father and aunt Jadzia were deported to Kazakhstan in 1940 and back then, there were not the kinds of social freedoms associated with democracies that one now takes for granted.

I visited Poland five times between 1984 and 1986. I felt a deep sense of sadness for a beautiful country ruined by 40 years of socialism and people who were obviously being repressed. Poland was a depressing place at that time. It was heartbreaking to see how people were forced to live under a corrupt political system and my heart went out to them.

Bright colours today replace the 1980s buildings' dull and muted shades in Michael's photograph of the the Castle Square (Plac Zamkowy) in Warsaw's Old Town. The building immediately behind the column holding the statue of King Zygmunt (who moved Poland's capital from Kraków to Warsaw in 1596), for instance, is now a lime green, below. The remains of the ancient city walls serve as a solid reminder of the Old Town's World War Two bombing and survival.

Michael's photograph of people relaxing around the walls of the Old Town's Castle Square in the 1980s could well have been taken today, judging by the hunched shoulders concentrating on something that is definitely not a social media device. The giveaway is the dull paintwork on the buildings.

Nazi troops demolished Zygmunt's column during their annihilation of Warsaw in 1944, badly damaging the statue and leaving the buildings with few recognisable facades. The repaired statue returned to its site on a new column in 1949. The Old Town's complete reconstruction took two years longer. Michael's earlier photograph of John's house shows how quickly the post-war re-build deteriorated. Today scaffolding and builders' coverings form part of the Old Town's facade as upkeep continues. The photograph below shows the only side of the Market Square (Rynek Starego Miasta) not completely razed.2

Some of the restored houses in the Old Town's Market Square.

Warsaw legends tell of a mermaid who, while exploring the Vistula, rested on its Warsaw

banks. The city so impressed her that she decided to stay. At first she annoyed fishermen by tangling their nets and

releasing their catches. They decided to trap her but instead fell in love with her voice. A rich merchant did imprison her

but fishermen heard her cries for help and freed her. The mermaid rewarded them by declaring she would protect the city and

its residents.

This statue, in the middle of the Old Town's Market Square, is one of several mermaids in Warsaw.

_______________

On my trips, I stayed with a lovely family called the Woźniaks. They lived in the middle of Kraków, directly above the Kino Warszawa near the Wawel castle. (I never did watch a movie there.)

The Woźniak apartment above the Kino Warszawa, taken by Michael on one of his 1980s visits.

I met Mr Woźniak coming home by train from Holland. He had been on business there and his daughter, Marta, had joined him. They boardered the train in Rotterdam, struck up a conversation with me and found out my reason for visiting Poland.

Mr Woźniak, who travelled a lot throughout the Eastern Bloc, once brought home a VW Golf. However, his driving was rationed as he had to get petrol coupons. He told me that the difference between Poland and Hungary was that in Poland, there was enough money to buy goods and services, which were in short supply, and in Hungary, the situation was just the opposite! Driving would have been uncomfortable in any case. There was no maintenance on the roads in Poland. Potholes and subsidence were ignored and buses and trucks would pummel the road. But buses and trains were well-patronised because people didn’t have cars.

The Woźniaks asked me to bring tea with me to Poland because the Polish tea was ‘like cut grass’ and tasted awful.

Western goods could be bought from ‘hard currency’ shops but they were expensive and most Poles couldn’t afford to buy from them. I used to post the family the odd packet of tea from England as well as bring tea over when I stayed with them.

Michael, second from left, poses between Magdalena Woźniak and her brother, Tadeusz. Marian Woźniak is on the far right.

When I visited, the buildings looked neglected and appeared to me as though dogs had urinated against the walls and they weren’t cleaned. Many shops were tiny and badly lit. There would only be two lights working out of a total of, say, six that had been installed. The staff members were apologetic as they laboured under the effects of Soviet socialism, which included such phenomena as queues for items due to constant shortages. All the best goods in the country were shipped to the Soviet Union and the locals were given inferior quality goods.

Michael cannot remember the name of this Kraków street but recalls that it bordered the suburb “Cichy Kącik”

Many everyday items that we take for granted were rationed. For example, I learned from a man who I had met in an English hostel to take my own lavatory paper as the Polish kind was of very poor quality. You couldn’t buy staples such as meat, milk or sugar when you felt like it, or buy as much as you wanted. If you wanted meat, you needed a ration card, and these could be bought by Polish citizens. Sugar was rationed to stop illicit home brews of vodka.

Shopping in Poland was an experience. I was used to paying for something and walking out of the shop with it. Not in Poland in the 1980s. You had to take your goods to a counter, where a shop assistant would write out a chit. You then took that chit to the kasa (cashier) and paid for the goods. The chit would be stamped and only then could you go back to get your product. I found it frustrating.

Karol Wojtyła, the future Pope John Paul II, lived in Kraków as bishop, archbishop and cardinal. He worked and worshiped at the Basilica of St Francis of Assisi, on the left of this photograph.

I do recall asking the Woźniak family to take me to visit Auschwitz concentration camp to witness the devastation wrought there. They declined, saying they feared that for one so young (I was about 25), I would be scarred for life. In 1993, my sister Elizabeth did visit Auschwitz and found it a sobering experience.

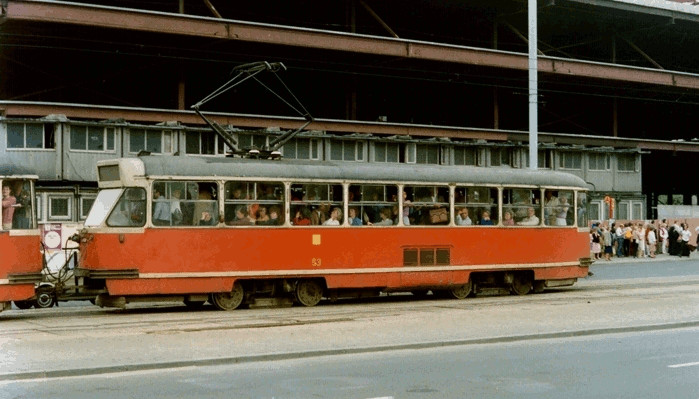

When I was in Poland, the trams were overcrowded and ancient. I know that there were trams in service that had been operating since 1945. In the city of Kraków itself, trams were the mainstay of public transportation services. Trams in Kraków were blue, those in Warsaw and Częstochowa red.

For Michael, a transport enthusiast, Poland presented a treasure trove of possibilities for photographs of trams and trains.

It was a shock for me to see policemen on every corner. They had the power to demand to see one’s passport, and regularly did so.

One day I happened to be out photographing trams and trains in Kraków when I was stopped by a military policeman. He asked me to accompany him back to the police station, which I did after he checked my passport for my identity. Once there, he spoke to me in excellent English and explained that no photographs in that area were permitted as there was a military base nearby, and that I had been taking photographs illegally.

I was unaware of any military installation in the background as I had been concentrating on photographing the trams, which I thought were rather exotic for someone who had grown up in a country without trams.

He asked for my camera, which I gave him. He then had the film removed, returned my camera to me and released me. He was very polite to me. I was annoyed, because it was a new roll of film and I had only taken two photographs, but I didn’t show it. Still, I understand that the man was only doing his duty. He had no choice.

At the time, I viewed the confiscation of my film as a violation of my privacy, but I was operating under my New Zealand mentality. It was only in retrospect that I realised the Poles were also operating under a foreign kind of thinking that had been imposed upon them and with which they had been brought up.

In Nowy Sacz I was fined 600 złoty by a railway policeman for merely pointing a camera. I had not taken a photo but since I had already paid for it, I took this one when he walked away!

Michael has no doubt that this image he took below of Białystok's railway junction fell under the same—or even stricter—rules, because of its proximity to the Soviet border.

When I look back on the history of the Polish people and the nation, I understand that over many centuries of occupation the Poles struggled daily to keep their culture, customs and language alive when everything else had been taken away from them. Therefore it was no surprise that they developed a suspicion of foreigners like me. When people don’t know any other way of life and when they are being constantly oppressed, they develop certain ways of thinking and mentalities which differ from our own. I didn’t blame the military policeman for what he did but I pitied him. Other people in authority such as priests were friendly and helpful to foreigners like me.

Back in the 1980s, Poland had a thriving black market. American dollars could buy you a good lifestyle on holiday. You had to be careful when dealing with the black marketers, though, because, if you didn’t count banknotes individually, you could end up being given a few złotych at the top of a wad of worthless paper. American currency was popular because Poles could use it to buy Western goods in hard currency shops.

There was another wonderful thing that Poland had which made me feel very proud of my Polish ancestry, and that was how in spite of a political structure dominated by atheists, Catholicism was very evident and the Polish people exhibited a strong faith in God, which helped see them through dark periods in their history when the Polish state ceased to exist.

I did a pilgrimage to Częstochowa to see the Black Madonna and I was awestruck by the beautiful statues along the Stations of the Cross and of course, the Black Madonna, the patron saint of Poland. Her portrait hangs in an awe-inspiring place, in a monastery on top of a hill in a forested area on the outskirts of Jasna Gora. I was so inspired by the beauty of the life-sized figurines on huge stones and marble plinths, I took photographs of all of them.

The actual Black Madonna portrait was positioned so far away, I couldn’t get close to her. That was disappointing but the whole experience was amazing and unforgettable. The faith of the Polish people that I witnessed was a beacon of hope in the midst of a sea of despair.

I was also impressed by the strong determination and even stubbornness of the people to keep their traditional Polish identity, values, customs and Polish culture, despite overwhelming odds against them, a trait which continues to this day and which has stood them in good stead.

In spite of not being allowed to exist politically as a nation for so many years, the Polish people have strongly resisted any attempts by other nations to change them. They have always shown such a fierce determination plus a faith in the own country. No matter what happened to the country itself, the Polish spirit never left the popular consciousness.

Ulica Spacerowa, the road in Białystok where Michael's paternal family lived before World War Two.

I visited Białystok on the east of Poland to see the street where my father lived and had grown up in as a child. Unfortunately, about two thirds had disappeared and the bend where the street was originally had been truncated, and led to a row of apartment buildings. Dad’s former home was no longer there. I concluded that the area had been bombed during the war and that Dad’s childhood home had been destroyed.

Two more images that Michael took in Białystok:

The top one shows one of the many post-war apartment buildings.

Michael stayed in the hotel below for three nights and remembers it as “not too bad.”

Visiting Poland was a good experience for me. I consider myself as just an ordinary person with a funny sounding surname and yet I’m proud of that heritage. When I returned to New Zealand, I was able to understand my father better.

I remain proud of him and his achievements. In 1986, my father was instrumental in helping to organise the Polish portion of the special open air Mass held for His Holiness Pope John Paul II at the Domain in Auckland. Dad had a lot to do with the Polish Club; he was the Treasurer and President for many years. He often had conversations with other Poles in Polish and I was able to pick up and understand some Polish even though my siblings and I don’t speak it.

Although Dad never spoke to us about his experiences in Khazakstan, and the immense suffering he witnessed, he did mention that during his stay there, ordinary Russians he met were kind to him and other Polish refugees. It was the authorities of the time who were to be feared.

Michael's grandfather Stanisław Jarka and aunt Jadzia in Białystok. Stanisław had just bought his daughter the coat she is wearing.

Another matter that was dear to my father’s heart was the massacre at Katyń Forest in Russia, which claimed the life of my grandfather, Stanisław Jarka, in 1940. Dad kept a copy of the last postcard his father sent his stepmother in December 1939. It greatly affected him. He and his sister grew up as orphans and were separated from their stepmother somewhere in Siberia. [See their stories in the Pahiatua section of war immigrants.]

It was with relief and sadness that my father and other Polish families greeted the news in the 1990s that the Russian authorities admitted responsibility for the Katyń massacres. This was done under the glasnost (głasnosti) policy.

I can also see how even ordinary Russians were victims of the siege mentality and madness of the Communist regime and that Mikhail Gorbechev had tried to undo some of that thinking with his glasnost policy.

I did not think much about my Polish heritage once I came back to New Zealand, but I’ve always been acutely aware of the terrible suffering that my father and others like him went through.

This studio photograph was taken in 1987, after Michael returned to New Zealand. It was the last Jarka family photograph taken before Rozalia, far left, died in December 1999. Rozalia witnessed Michael's graduation in September 1996 but by then Elizabeth had secured a job as a Hansard parliamentary reporter in Sydney.

I hold joint Polish and New Zealand citizenship, like my father and sister, and I am proud to be called a Pole.

My wife, June, and I are a testament to the apparent six degrees of separation in life. In Palmerston North, on 1 November 1944, June’s dad, Allan Hughes, was one of the school children who were given a half-day off school to gather up sweets, toys and other treats and meet the train carrying 733 Polish children and their 105 guardians from Wellington to their refugee camp in Pahiatua. Palmerston North was a coaling and watering station for the steam engines. The train was supposed to stay for half an hour but it stayed for more than two hours as the New Zealanders greeted the train, which stopped in their town, and the children walked up and down the aisles offering their gifts to the Poles.

Allan, 12 at the time, was struck by the sadness in the children’s eyes and happy when they started smiling, despite the language barrier. He doesn’t remember whether he actually spoke to my dad, but in time became my father-in-law. Later, one of the Polish girls on board that train boarded with one of June’s aunts and another of the refugees, Michał Gliński, later taught Allan art at night school. [See the language of children]

My dad spoke with affection about the warm welcome and good treatment that he and the other refugees experienced once they were in New Zealand, especially at Pahiatua.

© Michael Jarka, 2013

Updated September 2017

POSTSCRIPT: Jan Jarka died in 2008, Stella Jarka in May 2015 and Elizabeth Jarka in October 2015.

PHOTOGRAPHS: Most from the Michael Jarka collection.

Barbara Scrivens took the five modern photographs in Warsaw.

We have been unable to find the photographer of the image showing the 1944 Warsaw ruins.

ENDNOTES:

- 1 - The website http://99percentinvisible.org/episode/episode-72-new-old-town/ gives

more examples of the ‘improvements’ Bellotto made to the buildings he painted. In the website's story, Amy

Drozdowska and Dave McGuire spoke with Warsaw-born anthropologist Michał Murawski:

“Not long after the Old Town was rebuilt, people started to notice that it was a little bit off. People wandered around… feeling this uncanny disjuncture between the city that they remembered and the city in which they now found themselves.” - 2 - Although this image appears often in websites, it is unclear who the original photographer was. We continue our efforts to find him or her.