Eleonora Wojtyga Szukiel

Prof. dr hab. Eleonora Szukiel is one of life’s sunny people.

Her core of positivity guided her through World War Two as a child in southern Poland, a successful career in the

male-dominated forestry industry and helped her remain true to her values when it would have been so much easier to follow a

Communist line in post-war Moscow-controlled Poland.

The pani professor embraced what life threw at her, and adapted, but when she realised that she and her husband, Bronisław,

faced their final years in Warsaw without their daughter and granddaughters, she looked to New Zealand as more than an

occasional holiday destination.

Immigrating to the other side of the world at retirement age may have fazed lesser mortals but Pani Ela has taken the

transition in her stride. Her home in Warrington, Otago, immediately reflects her Polish heritage and love of the soil.

Tomatoes and lemon trees lined the windowed conservatory in her home when I first visited her in November 2016 and this year

in that spot she has several dozen figs swelling on a juvenile tree.

Pani Ela has exchanged Warsaw’s city streets and forests for walks along unsealed Warrington paths and on the beach at

Blueskin Bay, just 200 metres from her home.

Dziekuje Pani Eli and Panu Bronkowi za gościnność i cierpliwość. My very best wishes to them both.

Basia Scrivens

A TIME FOR WORK,

A TIME FOR REST

by Barbara Scrivens

Człowiek jest wielki nie przez to,

co ma, nie przez to, kim jest,

lecz przez to, czym dzieli się z innymi…

—Jan

Pawel II

A person is great not because of

who he is or what he has,

but because of what he shares with others…

—John

Paul II

Professor Dr. Eleonora Szukiel had what some would call the perfect life.

Besides a loving husband and daughter, she had a fulfilling job as chief of her department in a scientific institute, a comfortable apartment in the city and a home in the country that she and her husband used at weekends.

The Szukiels lived on Warsaw’s Ulica Szczęśliwicka (Happiness Street), about 15 minutes from the Varsovians’ favourite Szczęśliwicki Park,2 and an easy walk to and from work at the Forestry Research Institute (Instytut Badawczy Leśnictwa, or IBL). It took just 30 minutes to drive to their weekend retreat.

Yet that job, salary and prestige meant little in 1980s Communist-controlled Poland as far as Eleonora’s ability to buy even basic goods. Living in its capital city did not prevent her from facing shops with empty shelves.

Like most non-Communist Poles (Eleonora estimated about 80 percent), Eleonora and her husband, Bronisław, chief of his own department in the IBL, had to present coupons before making any purchases; nothing could be bought without that printed piece of soft grey card, not even half-litre bottles of vodka.

“It was very stressful. There was nothing to eat. Nothing in the shops, only jam and vinegar. I don’t know for how many years but everyone got a special ticket for meat, if there was some, one kilo of flour and maybe one kilo or a half of rice.

“Everyone had to stand in line at least three hours for such limited food. Usually it was my husband.

“I remember once our 18-year-old daughter stood in a long line for clothes. Nearly everything was finished, so she bought some tiny baby shoes and two pairs of baby [sleepsuits], ‘śpioszki!’ They were beautiful but I was annoyed about her idea of shopping.

“Another time, my seven-year-old nephew had to queue from 6am for milk and by the time he was at the front, they ran short. He screamed dramatically: ‘What will my baby sister eat?’”

One of the food coupons that Polish employers handed out to staff in the 1980s. This is

probably one of the last coupons that Eleonora received because it is dated 1989-8 and Poland held its first free elections

in 1989.

Here, “mięso” is meat without the bone that Eleonora describes as poor-quality and usually stewing steak.

“Woł. Ciel. z kością” is meat on the bone. “Woł.” is “wołowe” or beef and

“Ciel.” is “cielęcina” or veal.

“Reserwa” refers to any reserve stock: If what a person queued for was not available, it allowed that person to

receive something else.

Years earlier, Eleonora and her brother Ludwik annoyed their father when they returned home during breaks from their studies, Ludwik at the Polytechnic Sląska’s Construction Engineering faculty and Eleonora at the Medical University of Warsaw.

“My father, Tomasz, was a ‘peasant’ but he was always interested in the political situation, not only in Poland; in Europe, all over the world. Sometimes father tried to ask us political questions, and then he said, ‘You know nothing!’ He was angry with us but we were very young.

“My father, besides arduous work on our farm—five-hectares—was actively engaged in social work for his local community. He was chairman for the local administration of the community council. He was not a member of the Communist party but was a member of The Peasant Party. He did lots of work for local infrastructure such as building roads in Łęki Górne.”

Eleonora and Ludwik appreciated the chickens, vegetables, potatoes, rye bread, butter and milk available at the family farm in southern Poland but not as much as they would have done at the height of food rationing and price increases in the 1970s and 1980s.

All the Wojtyga children were born at the farm in Łęki Górne, near Pilzno, between Tarnów and Dębica, Eleonora, the second, in 1936. She finished her schooling in Pilzno.

“During my studies at the lyceum in Pilzno, for summer holidays in July and August, we students had to work at the PGR (Państwowe Gospodarstwo Rolne, or State Agricultural Farm) with no pay. We were young and happy!”

Taken on 11 August 1953, Ela’s class at the State Agricultural Farm, the Brygada Rolna 522, III Pluton Henryków (Working Scouts). Ela is partially hidden at the back, left.

“As a best student, I was offered a scholarship to study in Moscow. I chose the Engineering Sanitation faculty. I was very excited and happy to go. However, there were endless application forms and very hard exams, which required a lot of extra work.

“I passed all my exams. All was settled. Then my mother said, ‘No,’ and refused to sign the last required form, a condition [to study]. She was afraid for her 18-year-old daughter…”

_______________

Łęki Górne is still a tiny settlement, the “upper” of two villages that make up Łęki. Łęki Górne has 385 houses and about 1,460 inhabitants. Łęki Dolne, the “lower” has 815 houses and about 3,150 inhabitants.

After the German and Russian invasions of Poland in 1939, which Hitler and Stalin conspired to occur within days of each other, this part of southern Poland came under German occupation. It caught men like Tomasz Wojtyga and others in the previously quiet countryside unable to do much for their country except protect their villages and families the best they could against German patrols.

“You hear about that, people in probably in every village, tried to warn against the coming German soldiers. Some neighbours put notices on their doors: ‘In this house there is typhus.’

“The Germans hate anything that is diseased, so they don’t come to this or that house.

“The picture I still have in my imagination is very deep and sad. In 1944 when the German army came back from Russia, about five soldiers came to our house, the house where I was born. I had at this time three siblings, Ludwik one year older, Kazimierz, two years younger and my sister, Maria, four years younger, so all small children. (Roman was born in 1951.)

“It was terrible. They asked my mother, ‘Where is your husband?’ ‘My husband,’ my mother said, ‘is absent. He is not home.’ And then they said, ‘If we find him in your house we kill him at once.”

“And my father was hidden upstairs. Upstairs was not for living, just for hay. It was terrible for my mother and for us because we could hear.

“One soldier went up the ladder with this gun, like a Kalashnikov, maybe longer, with a bayonet. And you know he is checking all the hay around the walls…

“This fat man sat on a chair and he says to us children to look at him. It was very frightening.”

_______________

Before World War Two, Bronek’s family lived in the Zacisze region near university city of Wilno. His parents, a brother and sister survived the war but German soldiers killed his 18-year-old sister Eleonora in 1944. At that time the Russians had returned to Poland and there were regular skirmishes along the front. During one of these Eleonora, a year younger than Bronek, and her friend Janina ran “recklessly” from the Szukiels house towards Janina’s parents’ house about two kilometres away. Both were shot dead.

As part of their deal with Stalin, Churchill and Roosevelt endorsed Soviet annexation of that area of Poland in 1945. It is now in Lithuania.

Bronek, born on Christmas Day in 1925, studied forestry at a technical academy in Russian Leningrad (now St Petersburg). After his studies, in 1956, a cousin in the Polish navy helped him move to Poland. He started working at the IBL in Warsaw and became head of its mechanical engineering department.

During Eleonora’s first year at the Medical University of Warsaw she lived in her uncle’s apartment. The uncle was a four-bar colonel and an acquaintance of Bronek’s cousin.

“His cousin wanted to marry me. I don’t know why, but I didn’t want to. He was handsome, a beautiful man with blue eyes. He was too handsome and maybe not so clever.

“He said to me, ‘If you don’t want to be with soldiers at this moment, I have a cousin who has come from Leningrad. I will introduce you.’

“So it was romantic history. We married in 1958.

“We lived for three years in a basement at the institute. It was one room with an iron-barred window. The director took the room from our neighbour and gave it to us, ‘the young couple,’ when we married. We shared a small kitchenette with two other families. There was no sink, or water in the kitchenette and we had to walk a long way for the bathroom we shared with the coal workers.

“When Bronek went on business trips, I tried to not use this kitchenette because I was afraid of our neighbour’s drunken husband. When I was pregnant, I spent many hours in the hall of the institute sitting close to the door-keeper. The IBL had a man sitting in the hall in front of the main entrance all day and night.”

Eleonora with Małgorzata, born in 1961, outside the Forest Research Institute. Their apartment window was the one on the bottom row, far right.

_______________

Eleonora joined the forestry institute as a chemist immediately after she finished her pharmacy degree at the medical academy in 1959.

She set about what would become her scientific life’s work, creating ecological and technical methods of protecting Polish forests from large browsing herbivores such as roe and red deer. She calculated optimum structures, densities and living conditions for their roaming populations. She devised tree covers and repellents that foresters successfully implemented from as early as 1960. Some of them are still used today.

In 1980 Eleonora became a member of Solidarność (Solidarity ), the trade union movement born at the then Lenin shipyard in Gdańsk on 14 August that year. By 1981 the government had instituted martial law and arrested the union’s leadership, scattering them in prisons across Poland.

Solidarność maintained a campaign of non-violent social action that included factory strikes and rallies, pressuring Poland’s Communist government to concede to political reform talks in 1989. Free elections were finally allowed in November 1989 and the first leader of Solidarność, Lech Wałęsa, became Poland’s first non-Communist president.

During Poland’s turbulent 1980s the IBL had a strong Solidarność union and Eleonora was proud to wear her membership badge.

“I remember very well because I was one of the first members of the Solidarity union. However, it is a state scientific institute and in every office in every institute there was a man—usually it was a man—an agent of the Communist party who was engaged to look for members of the union.

“My director and vice-director were members of the Communist party. They hated me for being a Solidarity member. For this reason I never received any award from the institute. I used to work very, very hard and some people who did nothing received special awards and money. I was young and it didn’t matter but it was not very pleasant.”

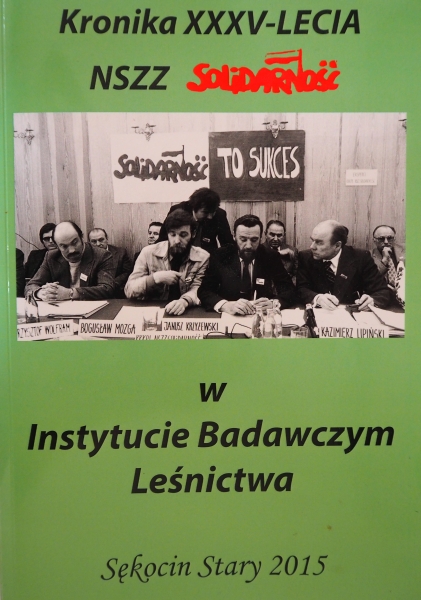

The Kronika magazine at the IBL celebrated the Solidarność trade

union's 35 year jubilee.

Kronika 35-LECIA:

NSZZ (Niezależny Samorzaflony Związek Zawodowy – Independent Self-Governing Trade Union) Solidarność.

Her appointment as head of her department surprised Eleonora. Perhaps the institute acknowledged that as well as her other duties Eleonora wrote prolifically on her scientific subject. By the time she left in 2001, she had more than 260 publications in her name, as well as several patents and textbooks, and had elaborated on her methods and findings in more than 100 other papers.

“The directors did not want me to be chief but some of my older colleagues died and a few of the younger ones emigrated. The directors did not want someone from Solidarity and I was also a woman. The forestry institute was a man’s place.

“As a chief of department I was often ‘agitated’ by the Podstawowa Organizacja Partyjna, or POP [small cells of the Polish United Workers’ Party that held power in the Communist-controlled Polish People’s Republic], that existed in every state institution.3 In IBL the two directors’ secretaries and two or three women in the personnel department were POP activists. Usually they were wives of high-ranking POP members and every week they went to the Communist party office to report on the IBL workers.

“There were about 20 departments and 80 percent of the chiefs of those departments became members of POP to protect their positions. I did not care to do that.

“When one my younger colleagues, an activist for POP, came to my office to recruit me, I answered, ‘For what? Tell me one value of this party and try to convince me that it worth to be a member of POP.’ He left my room without a word!”

Institutional politics did not sway Eleonora from immersing herself in her research subject. She was a dedicated scientist and a teacher, ensuring that those she taught knew how to put her scientific work into practice—and create their own—and she believed in sharing her findings with other similar Polish institutions.

_______________

Eleonora and Małgosia returning home from a święty Mikołaj (Saint Nicholas) kindergarten party.

Małgosia after receiving her First Holy Communion at the Saint Jakub (Swietego Jakuba)

church on Narutowicza Square (Plac) where the Szukiels attended Mass in Warsaw’s Ochota district. The square takes the name

of Gabriel Narutowicz, who was elected first President of Poland and assassinated seven days after taking office on

9 December 1922.

Below, Małgosia with her parents at the Łęki Górne farm in 1976.

At their weekend cottage in the Władysławów forest about 30 kilometres from the city, Eleonora could unwind between busy weeks and appreciate the reasons behind her research. Bronek, who retired in 1983, enjoyed the peace too.

The Szukiels’ forest cottage. Professionals built the shell in 1968 and Bronek completed the inside cladding and made beds, tables, cupboards, armchairs and benches. He also made some of the furniture in Małgosia’s Warsaw apartment.

“The cottage had four rooms, a fireplace and a beautiful garden. I had lots of chances to walk in the forest, a quiet, beautiful place, with Małgosia’s dog, a red setter.”

Małgosia had turned their lives around in 1990 when she married and moved to New Zealand.

_______________

One Sunday in 1999 soon after Easter, as they walked home after Mass through the Park Szczęśliwicki, Eleonora said to Bronek:

“What are we doing here, alone? Let’s go to New Zealand, to our daughter.”

Also missing in their lives were their two granddaughters, Maja and new-born Ola, living in Otago.

In a way, Eleonora and Bronek were responsible for Małgosia’s decision. After graduating with a psychology degree from the University of Warsaw, and practising in the city, Małgosia joined two friends for a year in England, to work and learn English.

“We gave her the money to start, and she worked. After the year the other two girls had enough money to buy a flat in Poland, but our daughter spent all her free time as a tourist because she already had the apartment, which we had bought her two years before. She met Jason, they fell in love, they married in Poland. His parents and a friend came from New Zealand and everybody was very happy.

“After the wedding they went to New Zealand. She promised that they would come back to Poland after a few years but it never happened. After we visited them in New Zealand in 1999, we could see they would never come back to us.

“I decided to finish my work. I could have worked up to today because now scientists, especially as a professor, can work up to 80, or even longer. In two years I tried to finish all my research, write my final book, sell Małgosia’s apartment and the beautiful cottage. We sent the money and asked her to look for a house for us.

“The two granddaughters were a great motivation for us. I thought, ‘I am exhausted.’ My more than 40 years of work at the institute, it was interesting work but it was stressful. I had my scientific work; I was supervising a few assistants for their doctors’ degrees; I had to find money for research for all the staff in my department; I was making trips to every regional forestry district to introduce my practise methods.”

Bronisław and Eleonora at Szczęśliwicka park in 2000, their last Polish winter.

Once Eleonora and Bronek made the decision to immigrate to New Zealand, she summarised her research in her final book for the institute.

Polish president Aleksander Kwaśniewski signed the Legitymacja that accompanied Eleonora’s Krzyż Oficerski Orderu Odrodzenia Polski (Officer’s Cross of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Poland) on 23 November 2000.

The Krzyż Oficerski Orderu Odrodzenia Polski was established in 1921 “for outstanding service to the state and society, and in particular for outstanding achievements in public affairs undertaken for the benefit of the country, for the particular merits of strengthening the sovereignty and defence of the country, for the development of the national economy, for outstanding scholarly, literary and artistic works, for outstanding contributions to the development of cooperation between the Republic of Poland and other countries and nations.”

One of the last things Eleonora did before leaving the institute was arrange a symposium to ensure that her ideas reached the widest possible audience and that her work would continue.

That symposium in June 2001 reflected the spirit of co-operation between forestry, biology and ecology research institutes in Poland and its 17 regional forestry districts. The 16 papers outlined the history of their specific area’s research and their results.

Advice Eleonora left her colleagues: “The team’s pursuit of large research programmes is worthwhile, as it avoids the simultaneous pursuit of similar themes by two authors at two or more centres. The execution of numerous small projects has lesser cognitive value, as it absorbs more resources and funding than one well-lit and implemented in a co-ordinated programme.”

Farewell letters from colleagues throughout Poland repeat their appreciation of Eleonora’s personal commitment and devotion to her research regarding the problem of hunting in Polish forests and protecting trees against wild herbivores such as deer.

In contrast to the days when the Communist party directors and chiefs frowned on her efforts, Eleonora is still remembered in the IBL’s milestone celebrations and invited to symposiums. She received an invitation to return to the institute to celebrate its 85th anniversary in 2015 but did not go as she had visited Poland the year before.

The legalities for gaining residency in New Zealand took the Szukiels two years. There was no Polish embassy and all the paperwork had to go through Sydney.

“I remember one medical doctor said, ‘You are both very old and you are going to New Zealand so you will be a problem for New Zealand to pay for.’ She was very unpleasant but we tried to stay silent because it depended on her, whether she agreed to sign the papers. You are small and under the table.” That old fear of authority remained in the back of Eleanora’s mind.

“What she said was not true. We have been living in New Zealand on Polish pensions. Bronek receives only symbolic support from Work & Income depending on the rate of exchange.”

Jason’s family lived in Warrington and that is where he and Małgosia found a house for Eleonora and Bronek, who sent additional money to help the young couple build a house of their own nearby. The excited grandparents arrived in Dunedin on 6 November 2001.

“Everything was prepared for us, even in the kitchen and bathroom, everything was there, groceries… cupboards full… Małgosia has lots of very good friends and they all helped. The garden was very nice, the lawn mowed and they even installed a new vegetable garden. In front of the roses there was a sign ‘Welcome Ela and Bronek.’”

_______________

Bronek and Eleonora in their Warrington garden in 2007. Eleonora made this “hill garden” on the heap of organic rubbish she gathered after planting fruit trees and shrubs.

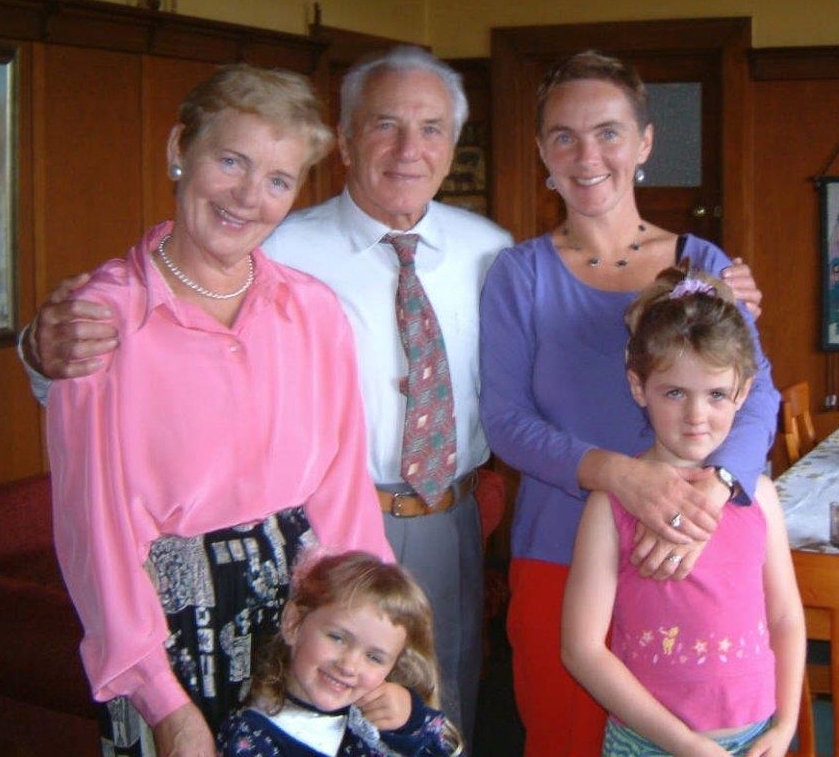

The Szukiels with Małgosia and in front Maja, right, and Ola.

Eleonora and Małgosia with Ola (left) and Maja at the Szukiel’s home in 2007.

The Dunedin coastal railway line is the Szukiels’ northern neighbour. A nightly goods train barely bothers them and Eleonora waves to the driver and tourists when the Seasider runs past once or twice a week, and the driver toots.

In 2006 Małgosia and Jason bought a property in nearby Karitane to keep horses and breed sheep. Eleonora and Bronek fostered these three lambs, rejected by their mothers after they each gave birth to triplets during a freezing spring.

“They were almost dead from the cold and Małgosia asked us to bring them to life. We put them in front of the fire or the heater and slowly they became warmer. For three months Bronek and I were kept busy feeding them. Belinda was Ola’s favourite and they recognised each other.”

These days the Szukiels still keep four Scottish Gotland sheep in their neighbouring paddock, just to keep down the grass.

Ola with two of the saved sheep and some of the hens that followed.

The hens proved slightly tougher to corral. Eight-year-old hen, Emeritus, was the last. She frustrated Bronek by insisting on laying her eggs in the forest, a habit she picked up from one of the original six hens, a bantam who decided she preferred to sleep in the trees rather than the three-roomed henhouse, and taught the others to do the same.

“In winter the bantam used to sit on the back of a resting sheep, warm her feet and clean the sheep wool, and later the brown hens did the same. When we had two bantam cocks, they ‘fell in love’ with the brown hens and watched them going to sleep in the trees.

“When Emeritus was alone she wanted to be my friend and looked for me or Bronek in the garden. She sat near the couch when I used to rest after lunch and when I woke from my nap, she started to ‘talk’ to me.

“Sometimes when I went into the garden she quickly went into the kitchen to search for something attractive for eat on the floor.”

Emeritus investigates visitors in the front garden—Małgosia and the Szukiels’ friends Heinke and Peter Mathenson, who moved to Dunedin from neighbouring Waitati two years ago.

“It is lovely scenery here. For example, when Bronek is scything by hand, the hens used to follow him, looking for worms. It is like the farm in Poland from 50 years ago when people ploughed and the birds followed the plough.”

_______________

After moving to New Zealand, Eleonora surprised herself by cutting herself off from Poland and anything resembling her former occupation.

“I thought, ‘there is a time for work, a time for rest.’ I decided to look after my grandchildren. Ola spent a lot of time in our house. From the time she was a baby to 11 years’ old she loved sleeping with her babcia under the quilt. She still remembers the Polish children’s songs I sang to her.”

The second day of their first Christmas Eleonora took a walk along Warrington beach. Unbeknown to her a “rather large group of Polonia” were doing the same thing at the same time. A sudden thunderstorm precipitated a meeting. Eleonora saw the group sheltering under a large tree, approached, introduced herself, and invited them, Polish fashion, to her house.

“It was lovely to meet them and they still visit.”

Among the group was Cecylia Klobukowska, president of the Polish Heritage of Otago and Southland Trust, who already knew Małgosia. Cecylia encouraged Eleonora to visit Poland in 2010 and 2014. In 2013 Eleonora joined Cecylia and Cecylia’s late husband, Wojtek, in Samoa.

The Wojtyga siblings in 2010 at the family house in Łęki Górne: from left, Roman (Reniu, born in 1951), Maria (Marysia, born in 1940), Ludwik (Lutek, born in 1935), Eleonora (Ela, born in 1936) and Kazimierz (Kazik, born in 1938).

Those holidays spent with her brothers and sister were special. Eleonora spent time with each of her siblings at their homes. She reacquainted herself with Łęki Górne, where Maria and her husband still live for the summer half of the year (they spend the winter half at their apartment in Tarnów). Ludwik took Eleonora to the tourist destination Zakopane. She is glad she went—she returned home to Warrington with a “special impression” to remember but now is satisfied with her own piece of Polishness north of Dunedin.

Eleonora cherishes this photograph of herself taken at her parents’ farm in Łęki Górne in 1957.

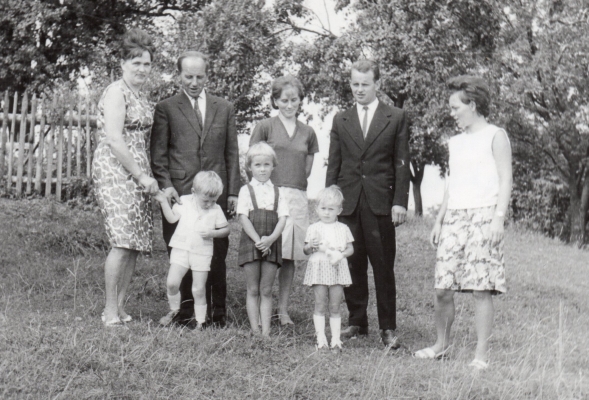

At the Wojtyga farm in 1967, Eleonora (far right) with (from left) her mother, Maria, father, sister-in-law Maria and brother Kazik. In front Małgosia stands between her cousins Renia on the right and Jurek.

Last year Eleonora celebrated her 80th birthday.

“It was a great party. Even dancing!”

Their Polish friends in New Zealand helped Eleonora and Bronek celebrate their 50th wedding anniversary in 2008. Here, Małgosia and Piotr Pater look on.

“We are happy. When we decided to move to New Zealand, Bronek was excited because he loves his daughter very much. He was so happy and said, ‘I want to live one year at least, only one year in New Zealand, close to our daughter.

“Bronek has always loved fishing and after we immigrated he liked to fish off the beach in Warrington or Doctor’s Point, and sometimes out to sea from Port Chalmers with fishing friends.”

Proud babcia Ela and dziadek Bronek with Ola, left, and Maja, about to celebrate wigilia in 2012.

These days Eleonora often dreams of the cottage she used to escape the cars and pollution of Warsaw.

“For 25 years or more it was my place to relax. I am surprised that I can still see so clearly back to Poland and the scenery of my garden around the cottage and the neighbours.

“Now, when Bronek complains about getting older and not having energy, I say, ‘Bronek, you said only one year, now we have been here over 16 years.’”

POSTSCRIPT:

Eleonora and Bronek celebrated their 60th wedding anniversary on 6 April 2018.

Polish Ambassador to New Zealand Zbigniew Gniatkowsksi helped them mark the occasion at their home by presenting special medals to them from the Polish government.

Bronek and Eleonora Szukiels married on 6 April 1958 in the Polish springtime. In New Zealand they celebrate their wedding anniversaries as their Warrington orchard is at its most bountiful. Left, the Polish Ambassador to New Zealand Zbigniew Gniatkowski and his wife, the Polish Consul to New Zealand Agnieszka Kacperska, joined the Szukiels for their 60th wedding anniversary celebration.

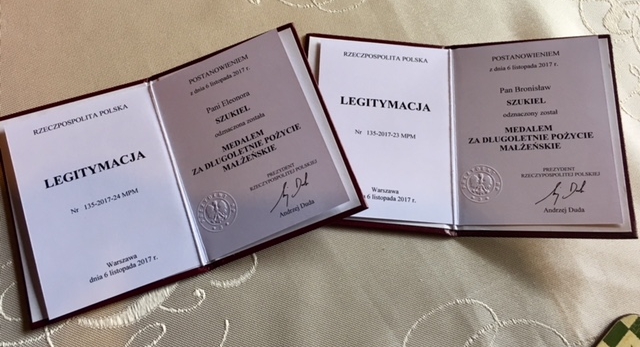

Ambassador Gniatkowski presents Bronek Szukiel with the Polish medal “For a Long-term Life of a Marriage,” 4 officially called the Medal for Long-Term Marital Deliverance (Medal Za Długoletnie Pożycie Małżeńskie). The unique Polish tradition to celebrate marriages longer than 50 years started in 1960 and is now marked in ceremonies involving more than 50,000 couples a year.

Małgosia and Ola joined Bronek and Eleonora at their medal celebration. Below, Eleonora's medal and the two legitimacje signed by Polish President Andrzej Duda.

© Barbara Scrivens, 2017

Updated March 2018

THANKS TO:

THE POLISH EMBASSY IN NEW ZEALAND FOR TRAVEL AND ACCOMMODATION EXPENSES IN DUNEDIN.

THE NORTH AUCKLAND RESEARCH CENTRE IN THE TAKAPUNA LIBRARY FOR THE LOAN OF AUDIO RECORDING EQUIPMENT.

ALL PHOTOGRAPHS BEFORE THE POSTSCRIPT COME FROM THE SZUKIEL COLLECTION.

THE FIRST POSTSCRIPT PHOTOGRAPH FROM THE POLISH AMBASSADOR ZBIGNIEW GNIATKOWSKI. THE REST BY CECYLIA KLOBUKOWSKA.

ENDNOTES:

- 1 - Jan Podmaski, Dyrektor Regionalnej Lasów Państwowych w Pile (Regional Director, state forest in Pila close to Poznań), used this reference in his letter of thanks to Professor Eleonora Szukiel on 20 June 2001.

- 2 - Szczęśliwicki Park (Happiness Park) was one of several built in Warsaw on top of rubble collected from the destruction of Warsaw. This one, on the immediate outskirts of the city, was transformed in the 1960s into a verdant park with a ski-slope on the highest hill in Warsaw.

- 3 - POPs existed in workplaces, colleges and cultural institutions in Communist-controlled Poland from 1949 to 1989.

- 4 - The inscription on the medal.