Bronisław Bojanowski

The Bojanowski family refused to give up or give in. Their strategising in 1940 and 1941 was a

life-and-death chess game facing expert Russian opponents who did not play by the rules.

This story emerged from several interviews with Bronisław Bojanowski in April and May 2014 at his home in Highland Park,

Auckland. Jadzia, his daughter, joined us.

The family became part of the forced exile and enslavement of some 1,700,000 Polish citizens after the Soviets—as

Hitler’s partners—invaded eastern Poland in September 1939. The majority of those Poles disappeared. Some died during

the brutal transports in crammed cattle cars. Starvation and disease took the lives of the elderly and most vulnerable.

Soldiers were mass-murdered; civilians more randomly. Pan Bronisław was among the eight percent of Polish soldiers and

civilians who managed to escape the USSR in 1942.

Pan Bronisław retained a keen memory regarding incidents that shaped his early life. He was the epitome of Polish

resourcefulness and fighting spirit and an inspiration. He lied about his age so he would be eligible to join the Polish army

and stopped fighting only when he stepped on a mine and lost a leg.

Pan Bronisław died peacefully on 22 October 2016 and now lies in Wellington beside the love of his life, his wife,

Daniela.

—Basia Scrivens

FAITH, SELF-BELIEF, COURAGE

by Barbara Scrivens

“Devastating” is how Bronisław Bojanowski described the that night Ukrainian neighbours working for the Soviets ripped his family from their beds on 10 February 1940.

Their family farm was one of 17 in the Chodkiewicze osada (settlement) in the Poczajów municipality and Krzemieniec district of Poland’s Wołyń province. Similar settlements scattered through rural eastern Poland after World War I. The closest city, Tarnopol, was about 50 kilometres south but there was no direct road link.

Local Ukrainians—under orders from the Soviet NKVD (Soviet secret police and precursor to the KGB)—forced Bronisław, his parents, and younger brother and sister onto their own horse-drawn sleds. In the confusion his older brother, Janek, escaped over the fields. The rest of that night and the next day Soviet soldiers drove the balance of the family to a large railway station a few kilometres inside the Polish border with Russia.

Bronisław, then 12, could not name the station but recalled overhearing his parents plotting ways for his mother to take advantage of the commotion and crowds. As their captors tended the exhausted horses, Anna Bojanowska melted away with Bronisław’s 10-year-old sister, Stefania.

This was not the place for self-doubt nor lingering farewells. Piotr Bojanowski, farmer and military veteran, boarded the waiting cattle wagon with Bronisław and Władysław, the family dog, three piglets, seven chickens and the luggage they had been allowed to gather the night before.

“They packed us like animals. We were really tight, a lot of people… about 30 in one wagon. The train was carrying animals before us.”

Bronisław did not remember any seating but recalled the bucket of porridge the Soviet guards put into the wagon every second day.

_______________

He did not know then that the rounded up Poles had become dispensable pawns in Stalin’s apparent revenge on men like his father, who had fought against the Bolsheviks in the Polish-Soviet War two decades earlier. Stalin identified them through the Polish post-war government decision to reward nearly 11,000 of those former soldiers with land in eastern Poland.

A German-Soviet non-aggression agreement allowed Stalin to avenge his flawed performance in the Polish-Soviet War.

The area was still being fought over long after the rest of Europe signed the Treaty of Versailles in 1918. The treaty had officially re-established Poland as a republic—after 146 years of occupation by the Prussian, Russian and Austro-Hungarian Empires1—but was slow to ratify Polish borders.

An uprising in the west clarified the Polish-German border but the “messy” war in the east, with numerous skirmishes from Warsaw to Kiev, ended only after a battle that became known as the “Miracle on the Vistula” and Polish victory in August 1920. The Treaty of Riga, formalising Poland’s eastern boundaries and signed on 18 March 1921, allowed the new Polish government to concentrate on rebuilding its second republic.

A German-Soviet non-aggression agreement enabled Stalin to avenge his flawed performance in the Polish-Soviet War.2 The agreement secretly assigned to Stalin roughly the same area of Poland that had been fought over 20 years earlier. German and Soviet foreign ministers Ribbentrop and Molotov signed that pact nine days before Germany attacked Poland on 1 September 1939. Stalin’s troops invaded 16 days later.

_______________

On that still-dark February morning in 1940 Soviet soldiers and their Ukrainian deputies forced approximately 220,000 Polish citizens—mainly former soldiers and their families—out of their homes. It was the first of four mass roundups banishing Poles to NKVD-run forced-labour facilities all over the USSR.

These “facilities” varied and were called different names. Single men and women arrested by the NKVD in Poland tended to be sent to prisons or gulags. Family groups were incarcerated at the closest point to the need for their forced-labour. Some of the facilities had been gulags, some had been hastily and roughly erected, and some occupied abandoned buildings.

The Soviet kidnapping of the Poles followed a carefully prepared plan, so audacious that local people were taken unawares.

These forced-labour facilities are often called “labour camps,” which belies the inhumane treatment of the inmates and suggests that the Poles deserved such treatment. A more appropriate term is probably the Polish “łagier” (pronounced “wahghyer”). The stroke through the first letter may be subtle but distinguishes the description of the Soviet forced-labour facility from the Polish “lagier” (pronounced “lahghyer”), a term reserved for the contemporary German lager or “concentration camp” with its own connotations of gas chambers and sudden death.

Polish families in the NKVD facilities generally escaped sudden death in groups, but died slowly through working and living in appalling conditions.

The Soviet kidnapping of the Poles followed a carefully prepared plan, so audacious that it took local people unawares. (See missing humanity.) Although the Russian army had invaded Poland months before, and Bronisław had heard his parents discussing what might happen to them, the family “didn’t really believe the rumour that Russia was going to take our property.”

_______________

Helping former soldiers into land from 1921 was not a completely altruistic move for the new Polish government. Marshal Józef Piłsudski, Poland’s Chief of State and the former revolutionary largely responsible for the country’s re-emergence, was aware that eastern Poland remained vulnerable to further invasion by the Bolsheviks. The former soldiers living in the previously disputed areas could be relied on to resist sporadic but on-going Bolshevik raids. (Piłsudski died in 1935.)

The land grants gave many of the young men a future they would otherwise not have enjoyed.

The land grants gave many of the young men a future they would otherwise not have enjoyed. They moved from all over Poland to settle in groups on often barren tracts between 28 and 32 hectares. Government assistance ranged from a moratorium on taxes to loans for building houses.

Piotr Bojanowski—like many other former soldiers—uprooted himself from his immediate family, in his case his parents' home in Wręczyca Mała near Częstochowa and the then-border with Germany.

Many of the new single landowners eventually chose local women with whom to share their lives. Established villages held regular gatherings, dances and celebrations of patron saints, and Piotr Bojanowski met his future wife, Anna Kozun, in nearby Panacówka.

Bronisław remembered one of their farm’s boundaries running a kilometre along the main road and their property as “flat and boggy.” It was a “tough life, working all the time outside” in extreme temperatures. Flies plagued them in the summer heat and he swatted them away from his ailing but “lovely” babcia (grandmother) who lived with them.

In this studio photograph, taken circa 1935, Janek stands next to babcia Kozun and Bronisław stands in front of Piotr. Stefania is next to Anna and Władysław is seated at the front.

Piotr’s experience helping his parents on their Wręczyca Mała farm made him well-able to break in his raw land and provide for his own family.

He grew wheat, barley and rye grains and planted vegetables in gardens closer to the house. The annual harvest of a half-hectare of potatoes was stored in a room and covered with dirt and straw to stop them from freezing during winter. Another half-hectare under flowering beans attracted bees. Water came from a well 20 metres deep, the full bucket's weight unwieldy at the end of the chain.

“Big jobs” always needed doing around the farm.

Piotr employed six or seven local Ukrainians during the harvest and sold his threshed grains through a Ukrainian friend in Łopuszno, about nine kilometres north. He and Anna spent days at a time there organising the sales and having other grain milled into flour.

Travelling along the roads was always convivial. No one hurried. Maps of the area show many informal routes and the few roads as “dirt tracks.” Bronisław remembers people working or walking along the roadsides exchanging greetings, “Good morning, good morning,” and “Szczęść Boże, Szczęść Boże” (God Bless).

Like most of the population, Bronisław was bilingual. Ukrainian children from the nearby village shared the school the osadnicy (military settlers) built and he made several Ukrainian friends.

After nearly 20 years on the Chodkiewicze farm, Piotr built a new house and stables. As was the way in Poland, in winter they moved their pigs to quarters attached to the main house to provide extra heat. The horses and cows remained in their stables. At the Bojanowski farm, an eight-metre-squared barn stored hay for animal feed.

_______________

That apparent friendship with the local Ukrainians is part of why Bronisław was so completely surprised at what happened to his family: They knew the people who woke them up so violently at two in the morning.

Perhaps Anna’s antics distracted the Ukrainians—suddenly the enemy—from recognising her plan for 17-year-old Janek to escape.

“They were smashing the door coming in, a lot of them, like policemen… it was over 16 or 18 degrees of frost (-16°C to -18°C), so cold it was squeaking. The snow was over a metre… and they had you walking on top of the snow.” Bronisław shook his head as he spoke of the noise they made as they trudged away from their home through the deep frost-crusted snow drifts and sat stunned in their sleds.

In a way, the Bojanowski family may have been fortunate that their aggressors were not Soviet soldiers—the local Ukrainians turned ‘policemen’ for the NKVD were possibly easier to manipulate than strangers. When the six or seven men barged into their home his mother started “screaming, crying, running, as if she didn’t know what to do.”

Perhaps she knew very well. After all, her family were locals too. With neighbours half to a full kilometre away, Piotr and Anna had to think quickly. Perhaps Anna’s antics distracted the Ukrainians—suddenly the enemy—from recognising her plan for 17-year-old Janek to escape. Bronisław remembers him “managing to run away” towards Wolica, about three kilometres from the farm.

“We worked so hard. It would be dark and my father was still working in the fields… and [after the Poles were gone] they put in Russian or Ukrainian people in our places. You work so hard and you lose everything…”

The seconded Ukrainians told the family that they were being moved to a different osada. Did they believe a story told to them by their new Soviet employers?

“We did not know we were going to Siberia. For us that was like from here to the next world.”

When Anna asked the Ukrainians what she could pack they said the family could take anything they wanted as long as it fitted onto their sleds. They left behind two milking cows, a heifer, two horses and a foal.

“… she grabbed my sister and walked away. She walked for two weeks, 70 kilometres, to her brother’s house in Tarnopol.”

“We took warm things, like the pierzyna (eiderdown) for covering and mum was planning… When we got to the station, everybody was so exhausted, the horses really had it, they could hardly walk. They were packing us onto the trains… Mum was crying.”

In the crowded station, Anna and Piotr worked out that she and Stefania would be ‘safe’ with her brothers in Tarnopol because they were not osadnicy. She must have given Janek the same instruction to head towards his uncle’s house because the three met on the road to Tarnopol.

“All the time [at the railway station] she was talking to my dad, how she was going to do it. I don’t know how she managed but she grabbed my sister and walked away. She walked for two weeks, 70 kilometres, to her brother’s house in Tarnopol.”

Anna had remained close to her brothers and the family knew the road well. Years later his mother told Bronisław what happened:

Anna disguised Janek as a girl. From afar, head covered with a scarf, her oldest son fooled the Russian soldiers—Anna looked like a local peasant with two daughters.

The danger for Janek remained, as any close inspection would show he was no girl. This worried Anna when she heard that the Russian army was looking for recruits and interviewing all young men. She outwitted them by covering Janek’s skin with petroleum jelly, making him look gravely ill. She got away with her ruse.

“Mama was very clever. One day, she went back to our house to get her horse, Meya. She went to the stable, got her horse out and by the time they woke up and started chasing her, she was on her way. They chased her for about 15 kilometres and couldn’t catch her—and she was without a saddle. She was great.”

_______________

A listing from the karta index of the repressed shows Piotr, Bronisław and Władysław Bojanowski were “Deportowani w obwodzie mołotowskim (permskim)” or, deported to the Mołotowska labour facility in the Perm region.3

Bronisław did not know how long the cattle train journey took. It is probable that they left from Łanowce. The KARTA Centre in Warsaw documented trains leaving from there stopping at Mołotowska. Łanowce was the closest large railway station to Chodkiewicze and became a departure station in April 1940 during the second wave of forced removals of Polish families.

“We were thinking we were going to be shot… Everybody was terrified… It was just that you didn’t know what was going to happen…”

“We’d stop and sometimes there was such a frost, 20 or 24 degrees (-20°C to -24°C), they couldn’t open the door. They were hammering to open it, to bring in the porridge. That’s all we had till we got to Siberia. People were lying on the floor and they were trying not to upset the children and the children used to lie down… We had one blanket, and another, but there was no mattress and you got bruises when you’re lying there… It was shocking.

“We had no idea what was going to happen to us. We were thinking we were going to be shot… Everybody was terrified… It was just that you didn’t know what was going to happen… They packed us like animals…”

Bronisław was certain all 17 of the Chodkiewicze families were taken—but separated—as he recognised only a few neighbours in his wagon. The tiny, narrow window high in the wagon-car made the interior dark and the occupants burnt coal in a stove in the middle.

“Otherwise, people would have frozen, it was so cold.”

The darkness and the speed of the train between the stops increased their fears.

“It was going quite fast, wobbling hard when it hit the connections on the railway lines, and we stopped quite often—something to do with changing the water for the engines.”

Their dog was warmth and comfort to the brothers—until he jumped down during one of the first stops and the soldiers did not allow him back…

One person in their wagon died, but Bronisław did not remember what happened afterwards. Adults protected the younger children as best they could but Bronisław was old enough to understand the enormity of what was happening, the feeling of shock and terror of the unknown as much as fearing their immediate danger.

Their dog was warmth and comfort to the brothers—until he jumped down during one of the first stops and the soldiers did not allow him back:

“He wanted to go outside to have a pee. He didn’t go on the floor and all he wanted to do is go outside and have a pee. They wouldn’t let him back in. He was such a lovely, lovely dog… beautiful dog… and we lost him.”

Human bodily evacuations were through a hole cut out of the wagon floor but his dog’s toilet training did not extend that far. The piglets disappeared but the family managed to protect the boxed chickens.

_______________

At the Polish railway station Bronisław could not see the beginning nor the end of the train. Its extreme length became clear only when it moved away after they were ordered off.

Again, horse-drawn sleds took the Poles to their destination deep in the taiga forest.

“After that, we find out that we are in Siberia.”

Technically Mołotowska—in the extreme south west of the Ural Mountains—is not in Siberia, classified geographically as all that area of the USSR east of the Urals. The few hundred kilometres made no difference to Bronisław—or to the hundreds of thousands of incarcerated Poles. The word “Siberia” for them meant any place of banishment into the more-than 22,000,000 square kilometres of the USSR.

“They were eating you while you slept and when you smashed them, they smelt horrible…”

Lengths of tree trunks lying on top of one another formed the walls of the wooden huts that Piotr and his sons lived in for more than 18 months. Wind blew freely through the numerous gaps in the roughly milled logs. A wood-burning stove, large enough to bake bread, stood in the middle of the room they shared with at least one other family.

“It was so cold, there was a whole family, six children crying, freezing. They used to sit mostly on top of the stove.”

The resulting warmth had a miserable downside—it brought out the pluskwy (hard black bugs) that lived in the logs piled next to the stove, and in the log walls and wooden beds.

“They were eating you while you slept, and when you smashed them, they smelt horrible. It was terrible. I don’t know how we survived…”

Food rations were usually distributed daily at the rate of 500 grammes of bread for a working person and 250 grammes for a child or non-working adult. NKVD guards took Piotr from the hut at 5am and returned him after dark. Although Bronisław was capable of joining him, looking after the chickens provided more valuable nutrition for the family than the extra bread.

“I managed because I had a brother helping and we were lucky because we had a few chickens that were still laying. I made a cage with the box that came with us and let them outside, making a place to keep them.” Bronisław had to keep the chicken run free of the prickles that lay all over the ground. After one weeding session, one lodged itself in his finger and created a boil. He went to the Soviet ‘medical’ officer, mistakenly thinking she would help him. He learnt his lesson when the woman roughly cut the nerve of his finger, he believed on purpose.

One fellow prisoner brought out extreme pity and a lesson for Bronisław in humanitarian behaviour:

“She kneeled at the door, the open door, and she cried, ‘Help me, help me, I’m dying… I can’t feed my child…’”

“I will never forget. She had a baby… She kneeled at the door, the open door, and she cried, ‘Help me, help me, I’m dying… I can’t feed my child. I have no milk in my breasts,’ and what do you do? We had chooks that were laying eggs…”

That memory remained raw for Bronisław. The mother had no husband or other family with her and when Bronisław confessed to his father that he had given her one of their precious eggs, Piotr agreed with his son’s decision. While their chickens laid eggs, they continued to share.

The Poles in Mołotowska had neither newspapers nor radios—nothing to tell them about the continuing war in Europe, or life outside their immediate surroundings.

The first too-brief summer arrived. The frozen river melted and started moving. Within two or three weeks the wood that the Polish captives had cut, and piled on the ice, surged downstream. A full Siberian winter followed, and a second summer. As another winter approached, they faced the reality that they would eventually die through cold, accident or hunger.

_______________

Piotr heard through a friend, who in Poland had been an inspector of teachers, that a Polish army was forming in southern Russia and they were allowed to leave Mołotowska and join. Piotr, at 44, was ready to enlist again.

Hitler broke the August 1939 German-Soviet non-aggression pact in June 1941 when he ordered his army to head towards Moscow.

The fact they suddenly had permission to leave became more important than knowing the reason why, but the inmates eventually found out that the war’s instigators had severed their allegiance. Hitler broke the August 1939 German-Soviet non-aggression pact in June 1941 when he ordered his army to head towards Moscow. This led to Stalin looking for—and finding—other allies. Poland was already a western ally and Stalin well-knew of the hundreds of thousands of conscription-aged Poles he had incarcerated in his NKVD facilities and who he could use to defend Moscow.

On 30 July 1941 Polish Prime Minister Władysław Sikorski and Soviet Ambassador to the United Kingdom, Ivan Maisky, signed an agreement in which Stalin gave ‘amnesty’ to the very Poles he had previously called “anti-Soviet elements.” (See military timeline.)

As Poles still living in eastern Poland exchanged Soviet for German occupation, the hundreds of thousands of those captured earlier by Soviets—and who had not yet died—could officially leave the USSR.

The Polish-Soviet Military Agreement, signed on 14 August 1941, carried stipulations that:

- A Polish army will be organised as soon as possible on the territory of the USSR and the army will become a part of the Armed Forces of the Sovereign Polish Republic…

- It will be destined to take part in the common struggle of the armies of the USSR and other Allied Powers against the German Reich.

- At the end of the war the army will return to Poland…

- Polish units will be used at the [German-Russian] front when they have reached full preparedness for battle…

- Soldiers of the Polish army on the territory of the USSR will be subject to Polish military laws and regulations…

- Armament, equipment, uniform, kit, motor vehicles etc will be supplied as far as possible, (a) by the government of the USSR, from their own stocks, (b) by the government of the Polish Republic from supplies obtained under the Lease-Lend Bill…4

_______________

Mołotowska's Polish inmates left the way they came—on sleds and in snow—but this time without horses. Their own questionable strength to pull the sleds disappeared with the melted snow and Bronisław remembered walking much of the way south-southeast to the Polish army enlistment stations in Uzbekistan.

They found a piece of wood… and left him… with his personal details and the message that his father and brother had left him behind.

For him, the journey had two distinct divisions—the first leaving his brother; the second losing his father.

Piotr and his sons discussed their options as they walked. Władysław had become so weak, they agreed they needed to get him into an orphanage. They found out that at nearly 12 years old, he fell outside an apparent cut-off age of eight. They found a piece of wood, some white writing material and left him where they knew he would be found, holding the wood with his personal details and the message that his father and brother had left him behind.

“There was no other way. He was crying but what could we do? They had to take him… and he was lucky.”

Bronisław and his father continued their journey to enlist.

Stalin may have wanted to use the Poles for the German-Russian front mentioned in the Polish-Soviet Military Agreement, but Polish authorities saw it as a chance to rescue their people. The difficulty of the Polish evacuation from the USSR under the auspices of the Polish army in 1942 is reflected in the number of Poles who managed to leave compared with the number incarcerated between 1939 and 1941. In his book an army in exile, General Władysław Anders uses the conservative figure of 1.5 million Poles removed to the USSR. He estimated “something under” 115,000 escaped—fewer than eight percent.

The Poles who received news of the new army’s formation were desperate to find it. Anders describes his first visit to a Polish army camp at Totskoie, where the 6th Infantry Division formed. He took his first parade of 17,000 soldiers:

… I shall not forget the sight as long as I live, nor the mingled pity and pride with which I reviewed them. Most of them had no boots or shirts, and all were in rags, often the tattered relics of old Polish uniforms. There was not a man who was not an emaciated skeleton and most of them were covered with ulcers, resulting from semi-starvation, but to the great astonishment of the Russians, including General Zhukov, who accompanied me, they were all well shaved and showed a fine soldierly bearing…

… I took the salute of a march past of soldiers without boots. They had insisted upon it. They wanted to show the Bolsheviks that even in their bare feet, and ill and wounded as many of them were, they could bear themselves like soldiers on their first march towards Poland.5

When Anders told Stalin the Polish army would not be battle-ready by 1 October 19416 it became apparent that the Soviet leader had less interest in having Polish troops fight the Germans in Europe and the Middle East than having them join the Red Army’s on-going battle for Moscow.

_______________

Bronisław described the Poles’ attempts to reach their army as bogged down with “unfathomable hindrances.” Soviet trains, even when they did stop to pick up Polish passengers, were no guarantee of reaching a destination. He and his father eventually managed to board one of the trains but not long after:

“My father went to get some water and the train just moved away—no warning at all—and left him behind.

“It was waiting [at a junction] for maybe three hours. My father went to get some water and the train just moved away—no warning at all—and left him behind. I was crying and praying and thinking ‘that is the end of me.’

“They did it deliberately, you know, creating shambles.”

Bronisław approached a clergyman he thought might help him.

“I was kissing his hands, holding him, crying. I said, ‘I want to go with my father.’ He said, ‘You’re not allowed to…’ but somehow, I was crying and he said, ‘All right, maybe we can get you somewhere, some orphanage somewhere in Kazakhstan.’”

It is unclear what this clergyman did after speaking with the distraught teenager but Bronisław's health deteriorated as rapidly as his sprits. All he remembered about getting out of the USSR is leaving the train on a stretcher and being taken to the “bottom of a boat.”

Cargo ships transported Poles from Krasnovodsk on the eastern shores of the Caspian Sea in then Turkmen SSR (now Turkmenistan). The Polish army arranged two sets of evacuations of soldiers and civilians in April and August 1942. Shortly afterwards Stalin closed the borders. Ships laden with human cargo made their way south to Pahlevi (now Bandar Anzali) in then Persia (now Iran).

“I couldn’t eat anything, I was losing weight, I was a skeleton. I had such bad malaria that I was shaking for hours, and then the sweat… you feel numb, like you are going to die. It took a long time to come right.”

Piotr had gone into hospital with dysentery and died… “shortly after having joined the army…”

Bronisław woke up in hospital in Persia.

“I was groggy, sitting in a chair. I looked up and there was this boy running up and down. It was my brother… a miracle because we left him in Russia. He had spots, a rash on his body—chicken-pox—and was not allowed to see me because he was supposed to be in a darkened room.”

When the brothers reunited years later in New Zealand Władysław confirmed that Bronisław had not been hallucinating.

Bronisław never saw his father again. He did not hold much hope for the man whom he had last seen standing among about 20 other men as the train pulled away.

“He didn’t have any money, he was eating scraps…”

Bronisław asked one of the Red Cross representatives in Persia to help him find his father. She confirmed Bronisław’s fears—Piotr had gone into hospital with dysentery and died. Bronisław did not know then that his father did manage to enlist, his name on one of two lists of Polish soldiers who died “shortly after having joined the army of General Anders in the Soviet Union” and who “perished at the various evacuation bases in Iran, 1942.”

Piotr died on 1 October 1942, nine days before his 45th birthday, at Khanaqin in Iraq and was buried in the British War Cemetery at Rafineria. The cause of death was not documented but “disease due to exhaustion” was common, according to Henry Sokołowski, editor of the website the soviet invasion of poland during world war two.7 This date makes it probable that father and son were both part of the Polish army's August 1942 evacuations.

_______________

As soon as he was well enough Bronisław joined one of the military cadet schools set up by the Polish army for teenagers not yet old enough to enlist. Known as junaki, some had parents or older siblings in the Polish forces, some had mothers and younger siblings in African, Mexican, Argentinian, Indian and New Zealand refugee camps.

Bronisław still had the end game in mind—to enlist into the Polish army as soon as possible.

These military cadet camps had a three-fold purpose: They were a place of safety and schooling. They were a training ground for the future reinforcing of the Polish army. Perhaps most importantly—they made sure that a generation of teenaged boys living without their fathers had adequate role-models. Most of the junaki were male but about 800 teenaged girls made up the SMO, the Szkoła Młodszych Ochotniczek (School of Young Volunteers).

Bronisław still had the end game in mind—to enlist into the Polish army as soon as possible. He decided early on to increase his age by a year. That way he would be able to join at 17 rather than the official 18. Several others did the same. With no one to know any better, Bronisław stuck to his story. This made academic classes more difficult, but he enjoyed the military aspect of the schooling system.

Six weeks before his official 18th birthday, Bronisław joined the II Polish Army Corps and four weeks later, on 2 March 1944, he left for three months’ further training at the Corps’ troop base in Italy—this time with genuine weapons, including the Thompson sub-machine gun and hand grenades.

Bronisław transferred to the 5th Carpathian Rifle Battalion. He saw action almost immediately in the battle for Ancona and later the Gothic Line, the northern Apennines and on the river Senio.

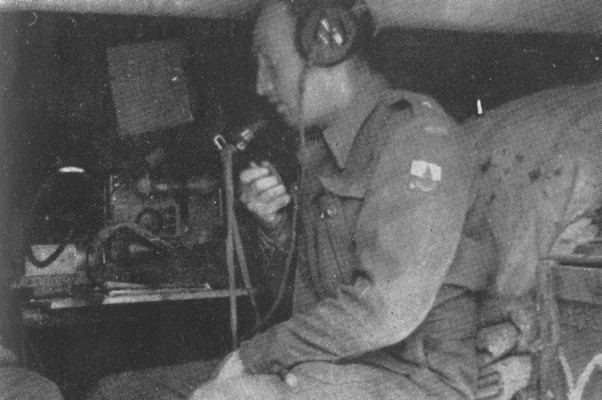

“I was lucky because my officer took me on as a radio operator. What he told me, I told the battalion.”

As a radio operator, Bronisław had to manage a fine line between keeping his communication line open and his radio battery from becoming flat. As much as the situation was precarious—the Germans could see the Poles if they moved during the day—Bronisław was in his element. He absorbed all that his officer taught him—hand signals and techniques learnt by the Polish soldiers in their previous battles for Monte Cassino and Piedemont.

A Polish radio operator sending messages under the ‘luxury’ of better cover later in the Italian campaign. He is near Castel San Pietro, between Bologna and Imola.8

In the interests of self-preservation, both sides tended to move after dusk and selected sleeping quarters judiciously. Soldiers knew that sheltering in abandoned houses invited the possibility of being trapped. They each had two blankets. If Bronisław and his companions could not find stables, they used hedges as camouflage and shelter, and branches for mattresses and coverings. They shared blankets and body heat. Although the hedges were open to the elements, Bronisław preferred sleeping under them to some of the “dirty stables” harbouring cockroaches enjoying the manure.

“Usually, they will tell us when we’re going to be attacked, so we can prepare, so we don’t really sleep but stay ready with the automatic rifle.”

All followed the “ready and quiet” mantra, especially when they needed provisions. The supply jeeps, stationed about two kilometres from the front line, crept along temporary tracks cut out of the hills under cover of dusk. They distributed bread and slices of bacon. Soldiers refilled their drinking canteens with water from wells. Sometimes, when food deliveries didn’t arrive, hungry soldiers found meals in farmhouses where women and usually young children still lived. Bronisław saw no Italian men. He remembers how Italian gestures for “sorry we don’t have anything” turned into a feast when money appeared.

“We were moving all the time, two or three kilometres, always moving towards the enemy.”

Even at night, any discharging of ammunition had to be judicious, “otherwise they’d know where the battalion is and would wipe us out.”

“You had to be very careful how much ammunition you had with you, you don’t want to be using it all too quickly and have nothing to defend yourself with. We sent our patrol out, they sent theirs, and sometimes we’d meet each other. We were moving all the time, two or three kilometres, always moving towards the enemy. It was hard.

“I was many times on patrol to find the enemy. We had to find out where the enemy was and all the time they’re moving and you had to be quickly orientated, otherwise they would see you and wiped you out. We were moving gradually, gradually until, until the end…”

Twice Bronisław’s patrol came across German patrols and took prisoners. He remembers the time he was in charge and ordered four ‘Germans’ to “hände auf” apparently understood as “get your hands up, weapons down, and fingers away from the triggers.” They all seemed to give themselves up but when one ran away, it became apparent that the remaining three were Polish.

“At first they didn’t know we were Polish, but when we started speaking they were so glad. They were children, boys about 16—younger even than I was—and they were scared because they knew that in the German army, they shoot prisoners.”

When the Germans invaded western Poland in 1939 they conscripted many Polish men into their own army—including teenagers not considered old enough to join the Polish army. The Germans used various coercion tactics, sometimes telling the young Polish men that if they did not join the German army their families would be killed. Other Poles joined on the German promise of their families receiving better rations.

Traversing the hilly terrain of the Apennine mountains held some challenges more uncomfortable than others—like when Bronisław’s patrol was forced to cross a stream.

“You’re looking at it. You can’t jump. You get water in your army boots, you can’t walk and you can’t dry yourself. It was horrible, my golly, but I volunteered so many times, I don’t know why, I just felt sort of risky, I thought, ‘We’re going to win. We’re going to win.’”

With wider rivers such as the Senio, above, Polish soldiers improvised with whatever materials they could find. Did they stay any drier?9

Although he chuckled at his watery discomfort, Bronisław became quiet as he remembered another incident: Some in his patrol entered an abandoned farmhouse while others swept the perimeter for German soldiers. Bronisław and a friend from the junaki stood in a barn filled with hay bales.

“We were talking. A chap hiding in the ceiling shot him while he was talking to me. We were just standing there. My friend fell. Another metre and I would have been gone too. That chap had a machine gun and shot my friend while he was talking to me.”

“That chap” turned out to be a Pole in German uniform. His officer stopped an incensed Bronisław from retaliating, pointing out the value of a captured prisoner they could interrogate. Bronisław’s dead friend was taken away by what he describes as special carrier jeeps, more armoured than the usual supply jeeps.

_______________

Bronisław’s British Ministry of Defence records show that he was wounded in action at Monte Gattone on 8 November 1944. He dismissed it as “shrapnel” but was hospitalised:

“I was thinking, ‘God, I’m not here to stay in hospital.’ They tried to save me but I didn’t want to be there. One day they put me on guard duty and I packed myself up and hitch-hiked back. I didn’t want to be in hospital. I wanted to be with my unit and my officer. He was lovely and he used to share. He had two children my age.”

Bronisław discharged himself and went to look for his unit, about 10 kilometres away. British and Polish army vehicles filled the road. One stopped.

“They saw I was in a soldier’s uniform and I put my hands up when they got close to me and they said, ‘All right we will pick you up.’”

Bronisław returned to his unit in the 5th Carpathian Rifle Battalion in time to join the II Polish Army Corps’ push north along the eastern side of the Apennine ridge. Back on patrol, he felt he could be of value. Part of the unit’s job was to look for landmines so they always walked carefully and about five metres apart.

“Then if one of us was lost, it was better than the whole group.”

During the battle for the river Senio in April 1945 the patrol found a footpath that “seemed so clear.”

This image, from the photographic publication 3 dywizja strzelców karpackich w italii (3 Carpathian Rifle Brigade in Italy) shows how innocent a path in wartime Italy could look.10

“I stepped on a mine, same as three others. My foot was half way off. I nearly lost the other leg as well. I had to wonder if I was still alive—I had three hand grenades on my belt and if any of them had exploded I would have been in pieces.”

Falling in and out of consciousness, Bronisław remembered the blue chalk cross the medics put on his forehead and those of others badly wounded and lying on stretchers in the corridor of the Field Dressing Station.

“There were quite a few casualties.”

Surgeons amputated Bronisław's right leg below the knee and removed as much shrapnel as possible. He spent three weeks at the Field Station and evacuated out of Italy through the Polish Military Hospital No. 3 in May 1945. He grew frustrated at being stretchered around by others.

“They said we were going to England. I felt numb, you know, depending on them. What was I supposed to do now?”

Bronisław went first to the Brechin Stracathro Hospital in Tayside, Scotland, and transferred in June 1946 to the Polish Military Hospital No. 11 in Ellesmere, Shropshire, where this photograph was taken. He is on the left.

Being an invalid did not sit well with Bronisław. While he “thanked God for being alive,” he hated relying on others for mobility, and the agony of his physical and mental pain.

The knowledge that his sacrifice was for nothing compounded his misery at being unable to walk unaided.

The VE (Victory in Europe) Day celebrations in London on 8 June 1946 did not include Polish fighters, the snub making it clear there was no free Poland to return to.

“We were really disappointed [about] the way Britain had done the negotiations and gave Poland away. We had a government, farms, kept the roadsides clean. We worked hard but we had a lovely life… I had a choice to go back to Poland [after the war] and I would have a good pension but where would I go? The Soviets took my home.”

Bronisław had no personal photographs of his time in Italy—“you don’t have cameras when you go to war.” His unit remained there for more than a year after he left, most of the soldiers ignoring the pressure to return to what had become communist-controlled Poland.

The photographic memories he did have were those taken in and around the Convalescent Invalids Depot that became part of the Polish Resettlement Corps in the UK (see explanation later).

Bronisław’s distinctive hair makes him easily recognisable in the back row of this group photograph taken at the camp attached to the hospital near Ellesmere.

The photographs here were all taken in the vicinity of the convalescent depot and hostel between June 1946 and late 1947 when Bronisław left for New Zealand aboard the ss mataroa.

Bronisław remembered that the friend in the photograph on the right went to Argentina.

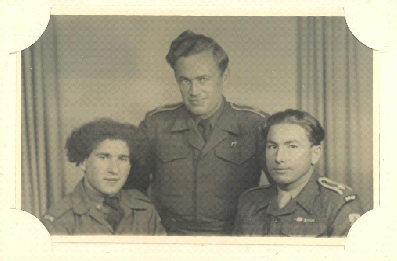

In this studio photograph Bronisław remembered the man in the middle as a pilot named Koswoski and that the man on the right also lost a leg.

Bronisław's comment regarding his relaxed upright stance: “You don’t want people to know you haven’t got a leg. That’s why you stand as if nothing is wrong.”

_______________

As well as receiving three British Service Medals, Bronisław ended his nine hectic months in action with the Polish Cross for Valour and an Honorary Distinction for Wounds and Bar. Here he is ready for Anzac Day commemorations in April 2015.

_______________

Anna, Janek and Stefania Bojanowski survived the war in Tarnopol and, after their city became part of the Soviet state, moved to Gdańsk.

Before Polish soldiers in Italy had fired a shot, Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin had already decided that Poland's post-war border would follow the one drawn in 1939 by Hitler and Stalin. Despite being partitioned by Austro-Hungary between 1772 and 1918, and never by the Russian Empire, Tarnopol was taken from the Poles.

The new Soviet-controlled Polish government relocated Poles in the eastern regions to western regions and those parts of Germany on the east of the Oder-Neisse rivers relinquished by the Germans as part of their surrender. Because that land had previously been annexed from Poland by Germany, Poland called the new western area “Recovered Territory.”

Formalities regarding Polish land transfers were signed at the Potsdam Conference in 1945. Stalin remained the Soviet representative, but new US president Harry Truman replaced Roosevelt, who had died months earlier, and new British Prime Minister Clement Atlee replaced Churchill, emphatically defeated in Britain's July 1945 general election. At the same conference, Truman and Atlee endorsed the Moscow-imposed Provisional Government of National Unity as the new regime in Poland.

Władysław, meanwhile, had arrived in Wellington on 1 November 1944 with 837 other Polish refugees, mostly children. The various Polish orphanages set up as Poles departed the USSR accepted many other ‘older’ children: There were 29 teenagers Władysław’s age (14) as well as thirteen 15-year-olds, seven 16-year-olds and three 17-year-olds. After the war in Europe ended the Red Cross helped Polish refugees find their parents and siblings.

The Polish Resettlement Corps (PRC) in the UK accommodated Polish soldiers who refused to return to Poland. The two-year stop-gap provided education and jobs, and allowed the Poles to learn English. Bronisław did not need that time. On final discharge from the PRC on 26 November 1947, he joined his brother in New Zealand.

Bronisław and Władysław were determined to sponsor their mother’s migration to their new country. Anna Bojanowska—actress, horsewoman and heroine—arrived in New Zealand in 1958, eventually remarried, and lived in Christchurch. She moved to Wellington after her second husband, Stanisław Lipinski, died in 1972 and the brothers took it in turns to accommodate her until she died in 1986.

The brothers planned a trip to Poland to see Janek and Stefania. Before they went they made sure they were naturalised New Zealanders—to guarantee that they would be able to return to New Zealand.

“We were still scared that if we went to Poland, they would take us to Siberia again.”

Bronisław married Daniela Lemów in 1949, pictured here at a Polish dance in Wellington.

Bronisław sealed his New Zealand citizenship in December 1959. Władysław, his wife, Czesława (née Jakowska, another Pahiatua child), and Daniela received theirs in February 1966. The four returned to Poland for the first time in 1970.

Meeting Janek and Stefania again was “great, it was like a miracle.”

By then Bronisław had trained as a tailor, his first job as a machinist at Vance Vivian’s in Wellington, where he made sleeves for blazers. He remembered with fondness a Scottish woman who helped him in the early days. He moved to car upholstery and retired from Todd’s Motors after 35 years. Apart from slightly limiting his choice of career, his false leg did not dampen Bronisław’s zest for life.

Bronisław arrived in New Zealand on crutches and moved into the hospital section at the same Pahiatua children's camp where his brother had lived. Daniela Lemów, another of the 1944 refugees, still lived there and worked as a nurse.

“She said she would take me around in the wheel chair. She was the one, so caring. There were lots of nice girls there but she was the one, really caring for me and I thought, ‘Thanks be to God.’ I fell in love.”

Bronisław and Daniela, born in Busk in February 1929, were married for 45 years, had two children, Jadzia and Zbysiek, and lived in Lower Hutt. Daniela died in December 1994 and Zbysiek in 1998.

“I found my angel in New Zealand. I still miss her.”

© Barbara Scrivens, 2015

Updated September 2017

APART FROM THREE MENTIONED IN THE ENDNOTES, ALL PHOTOGRAPHS ARE FROM THE BOJANOWSKI COLLECTION.

THANKS TO THE NORTH AUCKLAND RESEARCH CENTRE IN THE TAKAPUNA LIBRARY FOR THE LOAN OF AUDIO RECORDING EQUIPMENT.

ENDNOTES:

- 1 - The Russian, Prussian and Austro-Hungarian Empires partitioned Poland in three stages from 1772 to 1795.

- 2 - For further reading about the Polish-Soviet War, we suggest:

D’Abernon, Viscount, The Eighteenth Decisive Battle of the World, Warsaw 1920, Hodder & Stoughton, London, and

Davies, Norman, White Eagle Red Star: The Polish-Soviet War 1919-1920 and the Miracle on the Vistula, first published in 1972 by Macdonald & Co. (reprinted in 1983 by Orbis Books and in 2003 by Pimlico). - 3 - Searches can be done through:

http://www.indeks.karta.org.pl/en/wyniki.jsp. - 4 - Anders, Władysław 1949, An Army in Exile, The material is used with permission of General Anders’

daughter Anna Maria. The book was reprinted as part of The Battery Press Allied Forces Series, Nashville,

ISBN: 0-89839-043-5, page 53. - 5 - Ibid, page 64.

- 6 - Ibid, page 54.

- 7 - Site available through:

http://Felsztyn.tripod.com.

(The original publication used for the lists was: Wykaz Poległych i Zmarłych Żołnierzy Polskich Sił Zbrojnych na Obczyźnie w Latach 1939-1946, published by the Instytut Historyczny Im. Gen. Sikorskiego, Londyn, 1952.) - 8 - Album Fotograficzny 3 D.S.K. W Italii, cz 11, Sierpien 1945, Od Senio do Bolonii, 31-III-1945–21-IV-1945, second book, part 2, photograph no. 177, page 110.

- 9 - Ibid, Crossing the Senio, page 92.

- 10 - Ibid, part 1, Nad Adriatkiem, Carp. Engrs cleaning the ground, photograph no. 94, page 58.