Wisia Sobierajska Watkins

SEEING STALIN

by Barbara Scrivens

In the End, we will remember not the words of our enemies, but the silence of our friends.

—Dr Martin Luther King Junior.1

Wisia Sobierajska Watkins and other Poles in Teheran watched with dread as Stalin, Roosevelt and Churchill posed for official photographs after their conference in December 1943.

The Polish witnesses did not know then that behind the camaraderie on show, the leaders hid the planned secret betrayal of their country—but they knew enough about Stalin to be extremely fearful.

With heart pounding and only 20 metres away, Wisia at first could not believe the scene, and could barely bring herself to watch the “Big Three” on chairs among a group of uniformed delegates at the top of wide steps leading from the pillared portico of the Russian embassy. Although close enough to hear snippets of their conversation, she could not understand it—she had yet to learn English.

The photographs and newsreels taken that day at the Teheran Conference were meant to symbolise Allied unity during World War 2.2 In reality, they hid the duplicity of the three leaders, who had already met separately several times that year, and who had secretly decided the future of Poland, a country whose airmen had already played a pivotal role in the Battle of Britain, whose troops and airmen they had already used on the front lines—and whose troops they would continue to use in pivotal battles in France and Italy.

In public, they called Poland and ally. In private, they excluded Poland’s leaders from negotiations regarding its own post-war future.

Stalin had good reason to smile—he had the grip on Poland he wanted.

Wisia felt “horrible” seeing Stalin in the flesh—the man responsible for the deaths of so many hundreds of thousands of Poles, including her parents and two sisters. Stalin’s appearance and ease in the company of Roosevelt and Churchill shocked and frightened not only Wisia, but also other Poles in the crowd.

‘So many of us died and here he is still alive… here. We ran away from him, we have come so far and here he is following us.’

“We thought, ‘So many of us died and here he is still alive… here. We ran away from him, we have come so far and here he is following us.’ The [Polish] women with us started praying and said we should pray too that he would get zalania krwi [a stroke].

“We were scared because we thought he followed us. It was terrible, terrible seeing him. I could feel his evil even from where I was.”

In the previous three years Wisia had coped with incarceration in a Siberian forced-labour facility run by the NKVD (the Soviet Secret Police, forerunner to the KGB) and later starvation when Soviet soldiers abandoned her family and other Poles in a remote desert region of Uzbekistan—without food, water or a means to make a living. (See in and out of nowhere.)

Under Stalin's regime Wisia had witnessed, and survived, appalling deprivation. Her presence in Teheran as a Polish refugee attested to her inherent resilience. She was one of around 115,000—less than eight percent—of Poles incarcerated in the USSR between 1939 and 1941 who had managed to escape Russia with the Polish army in 1942.3

Her extreme visceral reaction that December day surprised Wisia—then 16 years old—as she had heard rumours that the “Big Three” were in Teheran, but did not believe them.

“We thought it was impossible for them to travel such distances. We didn’t know of aeroplanes travelling so fast then but a few of us got inquisitive and so we went to the place they were supposed to meet.”

Few of the Poles imprisoned by the Soviets for nearly two years had access to newspapers or the radio. The Soviets prevented the Poles from packing books, documents or any kind of writing material when they dragged families from their homes in eastern Poland in 1940 and 1941. Any news of the war—or the world—predominantly filtered to the forced-labour facilities through Soviet channels. Technical and aeronautical advances had by-passed most of the Polish refugees living in the tented Red Cross camp on the outskirts of Teheran.

If Stalin, Roosevelt or Churchill saw the smattering of European faces in the crowd, they did not let on. Wisia remembered the local Arabs cheering as the military delegation gathered on the portico.

Regardless of Big Three rumours, the sight of the Shah of Iran, Mohammed Reza Shah Pahlavi, leaving his palace in a more resplendent uniform than usual, drew Wisia and a friend to the city. They had created a game for themselves months before when, on their way back from their first trip into Teheran city, they noticed a “crystal castle.”

“It was so beautiful, sparkling in the sun. We had to stop and look at it and as we watched, a cloud came over and left, and as it left, a limousine came out. We hadn’t seen a car like that before. There was the driver with the hat and behind him a young man dressed with lots of gold.

“He was so handsome—even though he had quite a big nose—and we started waving to him and he waved back. So we used to come out from the camp hoping to see him, and quite often we did. And then we heard he was the Shah of Iran and he had invited us to stay in his country and that lovely castle was his.”

The Shah with his prime minister Ali Soheili and Winston Churchill on 30 November 1943.4

On the morning of the Teheran conference photographs the young Shah had no waves for the teenagers. Wisia remembers him “grim and stiff” as his limousine passed them.

Even though Wisia and her friend did not know the exact location of the meeting, they easily spotted the crowds milling around and the photographers on the upper steps of the embassy.

“No one was allowed too close.”

Stalin, Roosevelt and Churchill had already taken their seats when the teenagers arrived after their short walk following the Shah’s limousine.

Although the world expected the first official meeting between the heads of the three Allied powers, the venue was only publicly revealed after they arrived in Teheran on 28 November 1943. Roosevelt and Churchill made the trip together from Cairo, where they had finished a meeting with Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek and produced the Cairo Declaration for post-war Asia.

movietone news described Stalin as “Soviet’s great leader leaving his country for the first time in over 30 years.”5

If the Poles watching the photographs being taken were mortified at seeing the man behind the immediate past genocide of their people, they would have been more so if they had known of the ceremony that took place on the fourth day of the conference. Churchill presented Stalin with the Stalingrad sword. gaumont british news described the bestowal:6

… for the glorious past…, the gift from our king on behalf of all the peoples of the British Empire for all the heroic defenders of the great steel city in southern Russia… acknowledgement of the most gallant and most desperate stand in all this war, the victory that snatched defeat, the victory which turned the tide of fortune against the German invaders.

The australian war memorial, in its description of the ceremony, notes something not mentioned in either British news clip: The scene was edited because Stalin let the sword fall from the scabbard.7

The engraving on the sword, commissioned by King George VI and handmade by swordsmiths from the Wilkinson Sword Company, stated:

TO THE STEEL HEARTED CITIZENS OF STALINGRAD • THE GIFT OF KING GEORGE VI • IN TOKEN OF THE HOMAGE OF THE BRITISH PEOPLE.

The words reflected British attitudes towards Stalin and the USSR and British politicians glorifying the Russian victory over the Germans in Stalingrad.

During a parliamentary session in November 1943 British MP Walter Elliot:8

I do not know anything which has touched the imagination of the ordinary citizens of this country more than the gift given by the King of the Sword of Honour to the citizens of that city. In my own City of Glasgow alone 58,000 people lined up merely to go through a hall and see this gift of steel which was being made to the steel-hearted citizens of the steel city.

Elliot spoke after Anthony Eden, British Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, gave feedback on the on the “Foreign Secretaries’ Conference concluded in Moscow a few days ago.” Eden described “with absolute assurance” the 15 days they spent in the Russian capital as having “brought new warmth and new confidence into all our dealings with our Soviet and American friends.”

British newsreels describing the Teheran Conference a month later continued the positive message. As the final close-ups rolled past, the gaumont british news presenter voiced-over:9

These pictures stand for the hope that we all feel that doubt and suspicion on which tragedy and bloodshed feed, should be removed once and for all. The man in the street does not expect to know what is said in the secret consultations of his leaders. He can only judge by present appearances and results to come.

Wisia judged those appearances for herself:

“They looked worried but Churchill was puffed up, a bit cross but gave a little laugh. Stalin looked stubborn and stiff and Roosevelt just gave a little smile. Before they had to be still for the photographs, they spoke to one another but they weren’t smiling before the photograph was taken.”

Stalin brokered the same deal he had with Hitler in August 1939, giving the eastern half of Poland to the USSR.

Only when the war ended did Wisia and other Poles realise the three men posing in the chairs conspired to create a new eastern Polish border. In Teheran Stalin brokered the same deal he had with Hitler in August 1939, giving the eastern half of Poland to the USSR—the part of Poland that was Wisia's birthplace. She had been right to feel that chill at her unexpected encounter with the man she had every reason to fear and hate.

She may have feared Roosevelt and Churchill more, too, if she had known of their duplicity towards her country and the thousands of Polish officers who had been murdered on Stalin’s orders and buried in the Katyń wood near Smolensk.

That atrocity had only just started to smoulder publically but Polish military authorities had been worried for some time about the fate of thousands of Polish officers when they failed to enlist in the Polish army in 1941 and 1942.

Stalin insisted more than once that the Polish officers captured by the NKVD in 1939 had been released—but when Germany invaded Russia in 1941, its soldiers found one of the mass graves. For whatever strategic reasons, Hitler kept the discovery secret until Berlin Radio made the first public announcement on 13 April 1943—after Germany's defeat at Stalingrad—blaming the Soviets, who denied the claims. When Polish authorities asked the International Red Cross to investigate, Stalin broke off diplomatic relations.

Britain and the US backed Stalin’s version. Three weeks after the Berlin Radio announcement of the discovery, Eden said in the House:

…unfortunate difficulties which have arisen… between the Soviet and Polish Governments. There is no need for me to enter into the immediate origins of the dispute; I would only draw attention, as indeed the Soviet and Polish Governments have already done in their published statements, to the cynicism which permits the Nazi murderers of hundreds of thousands of innocent Poles and Russians to make use of a story of mass murder, in an attempt to disturb the unity of the Allies.

Eden’s linking of “innocent Poles and Russians” and “a story of mass murder” correlated unconnected events.

The mass graves at Katyń did not contain Russian corpses. Some of the thousands of Russians who died at Stalingrad may have been “innocent” but they had been armed, killed in battle by opposing German soldiers. They had a chance to fight back. The Polish soldiers and some civilians (there was at least one priest) found in Katyń and three other mass gravesites near NKVD prisons were unarmed, bound, and systematically shot in the back of their heads by Soviet NKVD agents.

The German announcement may have been retribution for the loss at Stalingrad and “an attempt to disturb the unity of the Allies” but it became another example of Stalin’s wish to “cut off the head” of Poland.

In a November 1943 parliamentary session in London, Eden alluded to “German propaganda” that was “extremely active” during the Moscow conference he had exuded about. In a barely veiled reference to the Katyń murders of what would eventually amount to more than 20,000 men, Eden said:

I hope… they will read the warning issued at the end of the Conference in the names of the Prime Minister [Churchill], the President [Roosevelt] and Marshal Stalin that those German officers and men and members of the Nazi Party who have had any connection with atrocities and executions in countries overrun by German forces will be taken back to the countries in which their crimes were committed to be charged and punished according to the laws of those countries.

Six months later British politicians continued to absolve Stalin of his crime, failing to accept that the finding and exposure of the mass graves occurred only because eastern Russia had been “overrun” by those German forces.

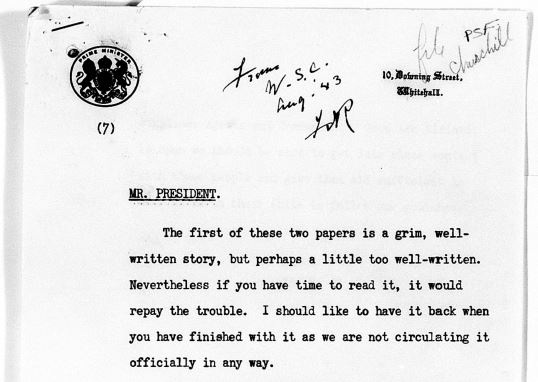

Both Churchill and Roosevelt knew of Stalin’s war crimes, as did Eden. Below is the first paragraph of the front page of a letter Churchill wrote to Roosevelt on 13 August 1943:

Owen St Clair O’Malley wrote that first “grim, well-written story.” As British ambassador to the Polish Government-in-exile in London during World War 2, he sent it to British Foreign Secretary Eden. In eight tightly typed pages, and dated just a month after the “glorious” battle for Stalingrad, it outlined the almost irrefutable Soviet guilt behind the mass graves

The report that followed was declassified in 1972.

In May 1943, Eden told MPs:

One thing at least is certain: The Germans need indulge in no hope that their manoeuvres will weaken the combined offensive of the Allies.

By December that year—in Teheran—he was proven correct. The Allies had a lot more to gain from having Stalin on their side than Poland. Outlining the “war situation” to the House a month after he wrote to Roosevelt, Churchill spoke of the “rapidly expanding weight of the United States Air Forces,” that the Allied Air Forces were “fed by an ever-broadening and improving supply of new aircraft” and that “the Russian Air Force is already at many points superior in strength.”

Poland, without such military might, seemed to have had lost its usefulness to the Allied cause. When Polish Prime Minister General Sikorski died in a suspicious air crash in July 1943, Poland also lost one of her few diplomatic weapons.

Wisia and her Polish companions did not bother to stay for the end of the photographic session that day in Teheran. After 10 minutes, she and her friend became “quite disgusted, fed up and cross” and left the politicians and the media to their tableaux. They walked back to their refugee camp on the outskirts of Teheran “dispirited and sad.”

At that time those two teenage girls probably had a better idea of where Poland stood with America, Britain and Russia than the majority of their still-hopeful countrymen.

© Barbara Scrivens, 2015

Updated September 2017

THANKS TO THE NORTH AUCKLAND RESEARCH CENTRE IN THE TAKAPUNA LIBRARY FOR THE LOAN OF AUDIO RECORDING EQUIPMENT.

ENDNOTES:

- 1 - The full quote:

Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that. In the End, we will remember not the words of our enemies, but the silence of our friends. Life's most and urgent question is, ‘What are you doing for others?’

Above from the Nobel site for Peace Laureates:

http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/peace/laureates/. - 2 - Photograph from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tehran_Conference.

- 3 - Conservative numbers taken from Anders, Lt-General W, CB, An Army in Exile, page 116. Originally published in 1949. Reprinted by The Battery Press, Nashville, ISBN: 0-89839-043-5.

- 4 - Still, taken from film reel: http://www.itnsource.com/shotlist/BHC_RTV/1943/12/09/BGU409100014/.

- 5 - http://www.movietone.com.

- 6 - Ibid. http://www.itnsource.com/shotlist/BHC_RTV/1943/12/09/BGU409100014/.

- 7 - http://www.awm.gov.au/collection/F01665/. The still was taken from the Gaumont News film clip.

- 8 - This and all the following quotations from the House of Commons come from debates between April and December 1943, published on: http://www.theyworkforyou.com/debates/?y=1943.

- 9 - Ibid. http://www.itnsource.com/shotlist/BHC_RTV/1943/12/09/BGU409100014/.