Jadwiga Jarka Cooper

A SHOEBOX OF RIBBONS

by Barbara Scrivens

In the middle of a 1940 April night in eastern Poland 12-year-old Jadwiga Jarka put on her best dress, packed her ribbons, socks, shoes and Panama hat in a shoebox, and readied herself to visit her adored father.

Maria, her stepmother, had earlier answered the heavy knocking of Soviet soldiers who barged into their Białystok home and ordered a frightened and sleepy trio, which included Jadwiga’s brother, Jan, to dress quickly and leave.

In the early winter of 1936 Stanisław Jarka and Jadwiga stride home from a shopping trip to the city to buy Jadwiga the coat she is wearing.

Eight months after the Russian invasion of Poland on 17 September 1939, Jadwiga followed the instructions given by one of the Soviet soldiers who had woken them. Eager to dismiss her stepmother’s voiced fears that her father had been killed in a west Russian prisoner-of-war camp, she accepted at face value the Soviet soldier’s story that they would be “joining” her father.

Three days earlier, another NKVD soldier had murdered Stanisław Jarka by shooting him in the back of his neck at a Soviet prison in Twer.

Jadwiga last saw her father when he rushed into their Białystok home in September 1939, hugged her, Jan, and Maria, and rode away on his police motorcycle.

After the German invasion of Poland’s western borders on 1 September, the Białystok mayor had left senior detective Stanisław, and a handful of others, charged with keeping “superficial care” in the city, and instructions to burn any tactically significant documents. The family knew his rushed farewell meant the Germans had reached the city’s outskirts, and he was following orders to escape on the motorcycle and join the Polish army.

“I remember father running along the garden path calling our names. We came out, and he dropped down and grabbed the two of us, and hugged us, and stepmother. He said, ‘Take care. I shall write to you as soon as I can,’ and then, ‘Goodbye.’ He didn’t even turn off the motorcycle.”

Unusually, Stanisław wore a major’s army uniform. If he were captured, he was to keep his career in the police force a secret, and pretend that before the war he had been a shoemaker, or any kind of labourer. Unaware of Stalin’s plan to invade Poland, Stanisław and others from Białystok drove east.

“Wherever they stopped they met Russians. One day they were ‘invited’ to leave their knapsacks and go into a canteen to eat. Their knapsacks were confiscated and they were taken to Kozielsk.”

Stanisław started writing postcards to his family, first from Kozielsk (Kozelsk), about 1,000 kilometres farther north from Ostaszków (Ostashkov), both Soviet prisoner-of-war camps in western Russia. (See Jan Jarka’s story on this page.)

Even after the censored postcards confirming Stanisław’s incarceration started arriving, Soviet soldiers—who had occupied Białystok later that September—routinely searched their Spacerowa Street home for him.

“They always came in the middle of the night, surrounded the house, and kept asking us, ‘Where is your husband? Where is your father?’ They must have known they already had him.”

_______________

The soldiers’ tactics changed on 13 April, 1940:

“They came at night, again surrounded the house so nobody escapes, thumped on the door, soldiers with rifles and bayonets. This time they came in brutally, just came in and demanded, ‘Get dressed, get the children… Hurry, hurry, hurry.’ It was all very military. Everything was in a hurry. They came at night—that’s why I hate nights—so as not to panic the population nearby. They did not want others [in the street] to know what was happening to us.

“Stepmother just sat on a chair, my brother and I on each side, holding on to her dressing gown and crying, the three of us. She couldn’t do a thing—she just sat there and cried.

“And as much as they said, ‘Stop crying and get ready,’ she wouldn’t. After a while, she said to them, ‘Go to the other room. I’m not dressing in front of you.’ And then they went, and she told us to get dressed, so I got the ribbons, because I thought, ‘I’m going to see my father: I have to look my best.’

“I had plaits, and a drawer full of ribbons, different colours, patterns, flowers, plain, chequered, different. In Russia, they were a godsend. Stepmother would take my ribbons, and barter with them, for food. Russian ribbons were very poor quality, two fingers wide, and red.”

_______________

After Stanisław left, and the Soviet army occupied Białystok, Maria went to work in the city hospital. The new occupiers forced her to take two Soviet officers as lodgers. Maria slept in the kitchen and the children in the lounge. Stanisław had acquired land closer to the river and, at the war’s breakout, had completed the foundations of a new larger house.

A neighbour’s house in Spacerowa Street in the 1980s. By then the street had been shortened and the Jarka house had been demolished to make way for a high school. Now, apartment blocks dominate the area.

Maria told the children they were lucky to get extra rations from the hospital canteen, but Jadwiga does not remember receiving anything special.

She felt wary with the Russian officers in their house—and deeply distrusted the one with bright orange hair—but Maria may have felt protected by them. Her crying that April night may have resulted from realising that she had been living in false security, or from clinging to the hope that by showing such emotion, they might have helped her.

“Our Russian lodgers knew what was happening, but played innocent. They didn’t say a thing. They didn’t go to open the door, didn’t come out of their rooms until we were leaving.”

Maria remained in tears and, even after she had dressed, she did not respond to the intruding soldiers’ pressuring her to hurry and pack for the journey. In the end, the soldiers gathered a few things “lying about,” and made her take the bundle with her as they escorted the trio outside.

“The lodgers said they would take the jewellery—all our family jewellery—and send us the money. I’m still waiting. They said they would send us the beautiful pictures we had on our walls. We should have had the presence of mind to take a few things, but we didn’t.

“We took very little, not even food. We left everything at home. Father hid money in the cellar under the potatoes, and we didn’t even take that. We had just the clothes we out on, and I had my summer shoes, Panama hat and the ribbons, and then we were on the truck and at the main railway station.”

Białystok railway station in the early hours of 13 April 1940:

“People were lost, parted from their families, looking for lost people, and crying. It was the saddest experience. It is still vivid in my head. It was such bedlam, crying, calling names, children lost, grandparents wanted to go with their family and being told they were too old.

“There was a long stream of wagons, as far as we could see. Stepmother held onto us, telling us, ‘Don’t part, don’t get lost.’

“We were rushed—so many people into each wagon—and, as soon as the wagons were filled, the door was shut, and we were off…”

_______________

In her light clothes—despite the lingering winter—Jadzia clung to her shoebox and thought of her reunion with her father. She admired his work as a police detective and as an International Security Officer protecting the Polish government’s foreign guests, even though both jobs limited the time he spent with them.

“He seemed to have a knack for detective work: One day he visited a farmer who had reported a stolen animal, a sheep or a goat. Father searched everywhere. It was winter and in Poland we prepare great kegs of kapusta, cabbage that we make into sauerkraut with salt and special spices, and there was such a keg standing by the door in this farmer’s house.

“So father ‘finished’ and the man said, ‘Thank-you,’ and my father—he was always chewing something, like a toothpick or a piece of straw—started to roll up his sleeve. ‘What are you doing?’ the man said. Father said, ‘I am going, but first I’ll just have a look in here.’ ‘Oh, there is no need to look there, it is just sauerkraut…’ My father put his arm to the bottom and pulled out the whole animal!”

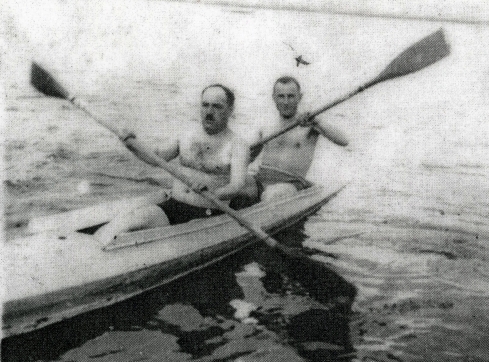

Stanisław, at the back in this photograph, would have stayed on the family farm in Pokrzywnica if a cousin had not suggested that he would be better suited to further study.

Stanisław Jarka married Rozalia Puka, moved to Białystok and joined the police force. Rozalia’s parents, Franciszka and Franciszek, lived in Czarnowo, a few kilometres south of Pokrzywnica, where both Jadwiga and Jan were born.

Rozalia made up for her husband’s regular absences by entertaining her children, often just Jadwiga, as Jan’s poor health led to his spending most of his time with their maternal grandparents in the cleaner country air.

Rozalia Puka Jarka

“Mama was lovely. She was always with us. She even played hopscotch in her high-heeled shoes. ‘Mama, please take your high-heeled shoes off.’ And all I could see was that when I grew up, I would have high-heeled shoes.

“Mama played, and we went visiting and picnicking in the forest, picking blackberries (czarne jagody) and cranberries (żurawiny) and mushrooms—not like the white ones here—special ones, borowiki (Boletus edulis) that you dry and preserve for winter, and many other types.

Jadwiga remembers fondly the picnics in the forest near their Białystok home. Here Rozalia and Stanisław Jarka are in the middle of the group in front of the standing girl. Jadwiga, with the straight white-blonde hair, is in front of her mother and Jan is on his father’s knee.

“In the summertime you did most of your living outside. We had a big table, seats. We played, and friends came.”

Białystok bustled in the 1930s. Bridges over the rivers connected boulevards, parks, and theatres, one built a few years before WW2 to commemorate Józef Piłsudski, who led the Poles to independence in 1918 and built up the Second Polish Republic, and who died in 1935.

“We went as a family to concerts, and to this day I remember the play about what was happening under the sea. It was enchanting.

“I had such a normal, happy life. Before we began school—at seven, not five like here—we frequently visited our grandparents, maternal and paternal, because there was not much distance between their two villages.”

_______________

Rozalia died during such a visit when she was only 26. Stanisław had spent a few days on the farm with the family during the summer, but had to return to work. He left knowing that Rozalia and a friend had planned to go to a dance that Saturday.

“My mother complained of headaches on Friday and on Saturday they got worse. She wasn’t getting any better so grandfather drove three kilometres to Goworowo fetch a doctor. The doctor spent the whole night with her and on Sunday when she couldn’t breathe, they took her outside into the garden—a very nice garden—and in the morning she passed away.”

Stanisław arrived back in Białystok to be greeted by his neighbour, a close friend and Jadwiga’s godmother, holding the telegram containing the news about Rozalia’s death. The last train back to Czarnowo had already left, so Stanisław had to wait until the next day to return. He walked along the main road towards the house where his dead wife lay, put down his briefcase, then veered into the fields. He had already taken his revolver out of his belt when villagers saw him, took away the weapon, and dragged him “like a drunken man” to the home of his parents-in-law. As was the custom in Poland, the entire village came to pay respect to the newly dead and he was greeted with a full, sombre house.

“He just knelt at the coffin. I was hanging onto babcia’s skirt and little Janusz was with dziadzio, holding his hand. All the village people came around, and said how sorry they were, and prayed. Then father said he had to go to town and get a new outfit for mama—she was too good to be buried in what she was wearing, her Sunday best.

“Babcia was distraught. She took it very, very badly. She had already lost one daughter, Zosia, and Rozalia was all she had.”

Zosia, older than Rozalia, had been playing with a friend who came from a noble family, at their house on the outskirts of Czarnowo, just as World War I started. The Russians deported them, with Zosia, to Siberia.

Jadzia on Franciszka Puka's lap, with Franciszek Puka, Rozalia and Stanisław.

“In Białystok, my father made several attempts to bring Zosia back to Poland. The final time, he and his contact went through half a dozen bureaus but—again—the last person did not sign the papers, so he couldn’t bring her home. It was the only time I ever heard my father swear. He said, ‘Cholera!’ and my babcia quickly reminded him I was in the room.”

“Babcia was corresponding with Zosia. Although Zosia was poor, she sent a little bag of rice or porridge. It was so very small that I was surprised it was so nicely packaged. During the war, she got away to Chicago with her second husband, Bolesław, and her youngest son, Leon, and left two other sons in Russia.

“So babcia only had Rozalia. People told us when we went to Poland in 1996 that mama was always happy and always helping, and that is what I remember about her. She would put the gramophone on, take me to the lounge, and teach me to dance. That’s where I got my love for dancing.”

Janek’s school, opposite Jadzia’s, had an ice-skating rink. One winter Jadzia tried to teach Stanisław a dance on the rink and told him of her plans to be a school teacher, with dancing as her preferred subject. Her father replied:

“That is all very well, Jadzia, but you have to be practical, because there will always be well-to-do people, no matter what the situation, and well-to-do people have money, and if you can become a dressmaker and make things—that will be your bread and butter and, perhaps, jam.”

This photograph, one of the last taken before Rozalia died, is one of Jadzia’s most treasured. It was Christmas and, as usual, her father had come in from work a fraction too late to have seen Father Christmas, who visited their home before the traditional wigilia on Christmas Eve.

Somehow, Stanisław Jarka never managed to meet Father Christmas, despite Jadwiga’s attempts. One Christmas, she grabbed his hand and lead him outside: “Daddy, Daddy, hurry, hurry, you may catch him,”

A rocking horse made the family’s last Christmas together unforgettable.

“We had a Christmas tree from floor to ceiling, decorated. My brother was the first going into the room. He saw the rocking horse. It looked real on the rockers, beautiful, black, and with a saddle. He got a fright and ran out.

“My brother loved horses. That past year [a horse] had a boil on its neck. My brother went to the stable where the horse was, and was going around his legs, wrapping his arms around each leg, and saying—he couldn’t pronounce ‘k’—‘Toń, moi toń.’ [‘Horse, my horse.’] We thought the horse would hurt him, but he stood still. My brother always loved horses, and that Christmas, he received one.

“We were enthralled with it. As a memento, our father arranged someone to take the family photograph. They covered the horse’s bieguny (rockers) with snow. Father gave Jan the reins instead of me, because he was a boy, and I was cross.”

The little boy against the fence to the left of Stanisław and Rozalia at the back of the photograph, was a German neighbour’s son. Stanisław’s ability to read people and situations made him suspect that German family of informing on him and others. He did not want to alert the German family, so remained friendly, but warned his children to “be careful” when playing with their children.

“We knew, with their lights at night, that they were signalling to the Germans.”

As soon as she saw German soldiers in their street in September 1939, Jadwiga suspected that they were looking for her father:

… once the Russians came in—as if you cut it with a knife—shops did not open the next day… because the Russians took everything to Russia.

“I was out, going to the dairy (shop) and I heard, ‘brrr, brrr, brrr’—motorcyclists. They stopped at the shops, opened their book and in German were confirming [from a map] this there and this there. I got such a fright, they seemed to know everything. They were looking for that German family, but the [house] numbers weren’t quite right because of a large open section that had not been built on.

“We were number 16 and they were 20-something and [later] there was a thump at the door and [the soldiers] came marching in—they were so organised, the Germans—and saluted us, said thank-you and asked after that number… Stepmother took them. That German family was supplying information, and my father knew.

“When the Germans occupied Białystok, everything was normal except we had a curfew. If you were found after 8 or 9 o’clock, you had to have a legitimate reason for being out. We didn’t have queues for bread or any daily products but once the Russians came in—as if you cut it with a knife—shops did not open the next day. There were queues waiting for nothing, because the Russians took everything to Russia. They deported us and brought their own people in.”

_______________

Stanisław’s marrying Maria only months after Rozalia’s death may have seemed callous, but Jadzia accepts her father made a pragmatic decision:

“When we returned to Białystok, his then-unmarried sister, Janina, came to look after us. He was so distraught after mama died, he couldn’t think straight… and then Maria contacted him… she and mama were friends from the same village.”

Maria must have known how bad the situation was for Stanisław in Ostaszków. He had worked out a code to let her know the real situation, should he be captured and be able to write to her:

“He had a fur car coat that he called Kożuszek [which he wore in the rocking-horse photograph]. ‘If I say I’m taking Kożuszek and lying down with him on the bed, it would mean the situation is very bad.’ And that was mostly what he said, ‘I’m putting Kożuszek on the bed and having a lie down.’”

_______________

In contrast to the mass removals of village settlements in February 1940, in April 1940, the Soviets targeted approximately 300,000 mainly women and children from cities—families of Poles arrested or captured during the first weeks of the Russian invasion. As in February, the Soviets used modified cattle trains to transport the kidnapped Poles to the USSR. Two months after Jadwiga’s transport, Soviets rounded up another 240,000 Polish civilians in the same way.

The following June became the last of that series of mass expulsions totalling more than 900,000 Polish civilians ejected from their homes at gunpoint and taken as forced-labour to the USSR. The Soviet operation stopped only because Hitler invaded previously Russian-held Poland and launched Operation Barbarossa on 22 June, 1941.

“I think the truth sank in when we saw those people coming and thumping on the wagons: ‘That’s our life now.’”

Maria should have been prepared to leave Białystok. While Poles did not talk openly about the February removals, the poczta pantoflowa (grapevine) ensured word came through and people who felt they may be Soviet targets were able to at least think about what they would do in a similar scenario, if not completely ready for it.

The Jarkas’ train transport provided some sustenance—wooden buckets of watery ‘soup,’, water and bread. The Soviet soldiers who packed Maria’s bundle at home did not include eating utensils, and the few who had them, shared. Jadwiga remembers one man had tools and cut a hole in the floor that they used as a toilet.

Armed Soviet soldiers guarded each side of each wagon from the outside. As their train drove through Russia, one stop shook her:

“We only stopped a little while but there were masses of people who surrounded the wagons we were in, and were begging. They were the poorest, in their old torn garments… on the point of starving: ‘Give me some bread. Give me something.’ It was such abject poverty, I did not know people could be dressed so poorly, or be so skinny. We didn’t have much, a few crumbs and a slice, and they were fighting over it.

“I think the truth sank in when we saw those people coming and thumping on the wagons: ‘That’s our life now.’ I thank God for our faith. We prayed like mad, we had to hope things would get better. Faith and patriotism—that was our sustenance.”

Jadwiga had picked up her father’s prayer-book as she left her home. She learnt verses from it for her First Holy Communion and in the USSR, it helped her to maintain a connection with her written language.

“It was his, and I wanted something I felt at home with. It was comfortable. He wrote his name in it, and verses about Communion. I recite them daily.”1

_______________

“There was a lovely lady in our wagon. Her family had the Bata shoe factory in Białystok. She really kept our spirits up. She would call to the soldier to open the door, praising him and calling ‘my darling’ and in Russian she would sing a ditty to him: If the soldier was kind, she would sing about ‘my soldier, who went sailing down the river’ and if he were to die, ‘Praise God, I will light a candle and pray for you.’ If the soldier was unkind, she changed the words to say she would not light a candle for him and would not pray for him.

“… She said to the soldier, ‘Take care, take care to bury my baby.’ The soldier took it and threw it out…”

“That helped us. I suppose some of the soldiers had a bit of pity for us, for the little children, babies… they felt something for us, and they would let us perhaps stay outside longer, or have the door open instead of shutting it straight away.”

Once the two large doors at the side of each wagon closed, the only light came through two small rectangular windows, high up and on opposite sides of the wagon. Most wagons had a one-ring stove. There was no conventional seating—the sides were lined with wooden shelving, wide enough to lie down on, but without enough space between them to sit on.

“It was so the Soviets could cram as many of us as possible inside.

“One woman’s baby died. It was very little. She dressed it in its best, and when the woman soldier took it away, she said, ‘Take care, take care to bury my baby.’ ‘Oh yes, yes.’ And the woman soldier took it away.

“There was a straight stretch [of track] and then a curve, so she saw the soldier in the wagon in front throw the baby out as we kept going around the curve. The poor mother went berserk. Did she scream! She was inconsolable. It took her a long time to stop crying.

“It was cruelty to the extreme. I often wondered how anyone could be so nasty to such a little baby, how much nastiness was in the Soviets to treat anyone in the unkind way they did. Then I thought, we are the enemy, and they are the enemy.”

The large proportion of women and children on that April transport may have left the soldiers feeling confident, but the Polish women could be devious.

“Two young boys, teenagers, escaped from our wagon and to this day I pray they had a better life.

“The soldiers with their bayonets were counting us all as we left the wagons to get the soup, water and bread, or nature calls in the open space. There was no toilet paper, nothing. You do your best. They go with the bayonets and they counted you so that the same number assigned to the wagon returned. We had little ones and we put two behind us again so they were counted twice.”

_______________

The train finally disgorged its load in a place Jadwia remembers as Gregorianka, somewhere in northern Kazakhstan.

“We were no more than beggars. We didn’t have anything.”

“It was May, the month of Our Lady, when we have special prayers. They packed us—about 60 families—into an old disused meeting house, the clay floor full of potholes, everywhere full of fleas. We started scratching ourselves, and I remember quite a big boy afflicted with something. They had to keep an eye on him because he could turn nasty… he didn’t speak, but kept groaning all day. There was no space to stretch your legs so we took turns sleeping.”

“The local kids came, called us names, because we were the enemy, threw lumps of soil at us, made themselves a nuisance to us.”

The older Poles worked on the collective farms. During a time haymaking, they lived in tepees among small, smouldering haystacks used to deter the giant mosquitoes. The smoke did not prevent Jadwiga from contracting malaria, which she carried until she reached New Zealand and was treated with quinine.

“They kept moving us to where they wanted the adults to work. They did the work, but they wouldn’t pay them, so what little food we had was consumed.

“The Kazaks would take their milk to a little dairy and they would get the same skim milk you get here and we asked them, ‘Could you give me something?’ Some of them could give but some of them said, ‘No, I have children. I have to feed them.’ We were no more than beggars. We didn’t have anything.”

Some of the Poles complained to “whomever was in charge” about the cramped meeting house. Jadwiga, Jan, and Maria joined a group directed to a stable with a room attached used to treat ill cattle.

“There was one varsity student, Janina… she tried to make us laugh. She was lovely.”

“We had to steal straw and branches and cover the missing roof in the stable—rain doesn’t care much where it goes. We finished covering the roof and had more room to sleep on the floor—clay—and then we got weeds and things from the river and spread it out to sleep on and cover ourselves… bull-rushes to make it softer.”

At one stage, the women were taken to build houses from straw, clay and animal dung and came back unable to rid their hands of the smell.

“They weren’t paid. We were in AUL-7 then, I think. We all lived in one big room in a house with two German families. I learnt German from their son, Hilary, and their cooking smell just about killed us, because they had fat and we had none.

“They made another ‘room’ as extra accommodation for other Poles, by excavating a long, deep trench. Only the windows were above the soil. Water seeped through; it was just raw soil. They packed it with Poles, from where, I don’t know.

“We were still too young to work. There was one varsity student, Janina. Her mother was a pharmacist in Białystok. She organised us and taught us Polish and maths, and when it was fine, we would go outside and write in the sand or the snow. They wanted us to know as much Polish as possible.

“Janina tried to make us laugh. She was lovely. Teaching us was a favour. She didn’t have to. She had another job. She taught us a concert that we could act out, about a little old lady, sitting and drawing and spinning wool… and eating and drinking too much. The last time I saw her was that little play. We moved, or she moved. They kept moving us.”

Jadwiga had by then stopped fantasising about a reunion with her father, “I was too busy worrying about hunger and fleas,” but her stepmother used her ribbons to barter for food. She exchanged the last ones for what turned out to be flour contaminated with bitter weed seeds.

“Getting something to eat was more important than the ribbons—the more we could get for them the happier I was—but that bitter flour, it was unkind.

“Each day you have a ration to make porridge. Just water and no sugar, no salt, just a paste. Sometimes we peeled potatoes and tried to make potato pancakes on the one-ring stove but they just fell apart and when you swallow, it burns you and you don’t know whether to swallow or spit it out. It was supposed to be cake. One day a horse died and people came to chop bits off.”

Jadwiga waited until another customer distracted the grumpy proprietor, and stole a watermelon.

Pavlodar, on the meandering Irtysh river, became the Jarkas last stop in Kazakhstan. The approaching winter and hungry howling wolves at night made the authorities force local villagers to open parts of their homes, however small, with the Polish labourers. The Jarkas shared a room containing a stove, and part of a corridor, with another mother, a grandmother and two other children.

The Irtysh flooded the railway and froze, and the Polish labourers had to lift the tracks. For their railway work, the labourers each received a daily 200 grammes of bread, and some cabbage ‘soup.’

“Even then, when they weighed out the bread, they tossed it down so quickly and sharply that it would push the scales right down. Then they would chop off a bit of the bread. Then they would throw it on the scale again and chop off a bit more, so we never got the full 200 grammes, and the bread was half-baked and heavy anyway. The soup had big green leaves in it, barely washed, and some potatoes floating around. It was 1941 and Janek was very sick. We were saying prayers for the dying over him.”

One day, when Maria had left with the others to pound the ice from above the railway tracks and lift the steel, an older person took Jadwiga with her to a market. She wanted to get something for her brother to eat besides their ration of potatoes and flour .

They took a train, stopped at a workers’ hut, then walked to the market. Jadwiga, holding a few “kopek,” wandered around the trade stalls looking for something nutritious, but seeing nothing she could afford.

She saw a trailer full of watermelons, but soon realised she did not have enough money for even the smallest. The woman in charge shooed her away when she opened her palm to expose her coins. Unable to get the thought of helping Janek out of her head, Jadwiga waited till another customer distracted the grumpy proprietor, and stole a watermelon. She put it on a table in the workers’ hut.

“Suddenly, I had to hurry to catch the train and I left that watermelon on the table. I cried and cried. I couldn’t get over what I had done. The devil prompted me to go and steal that watermelon so Janek would have something to eat, and I went and left it on the table.

“Then stepmother met a Polish soldier in one of those long army coats, like my father had. He was trying to find his family. In his pocket he had one little apple to give to his family.

“… There was no cleanliness, just wet and dry. You take your garment and you kill the lice in the seams.”

“Stepmother invited him in, and we shared whatever food we had. I don’t know what happened to him, but he gave this apple to my brother because he was so sick. Stepmother washed it, took the core out on the stalk and gave it to me. I ate it so slowly, even the stalk…”

The apple flesh helped Jan, still too weak to sit up in bed. Jadwiga then met an elderly Russian couple who, once they knew how ill her younger brother was, gave her milk, cream, butter and “other bits and pieces.”

“I called them babcia and dziadziuś [grandmother and grandfather]. From the first, I liked them, felt close to them, and we started talking. One day they opened up a kufer [trunk] and showed me all their hidden photographs of Our Lord. They were Orthodox and not allowed to have such things visible. Nothing religious was allowed.

“It was the same with us in Poland during the Soviet occupation. They turned our church into a cinema. Garrison soldiers, anybody, used to go there. It wasn’t a church anymore.”

The generosity of the elderly Russians who gave Jan back his strength contrasted with a “rascal” of a Russian neighbour, who found out that the grandmother living with them had a parcel containing tobacco delivered from Poland. He offered to bring them some timber for fuel in exchange for the tobacco. The grandmother agreed. The “rascal” took the tobacco without delivering the wood.

The betrayal came as a snowstorm battered the area for days, and covered the houses. In their corridor-shelter, the snow became too deep to dig away and, without fuel for the stove and water freezing in their bucket, the seven huddled together for warmth.

“You couldn’t see the houses. They looked like a mountain ridge. On one side [of the corridor] we would take a bit of snow to moisten our lips. On the other side, we would empty the potty. We had nothing. We could do nothing else, we were freezing.

“The owners [of the house] said that their family was coming, so we had to leave. We went to a stable. My brother and I had to sleep in a dog kennel. If you wanted to stretch, you had to open the door, but it was so cold, we shut the door.

“You were forever hungry. We slept in the same clothing as we worked. In summer at night-time, it was a ritual to go to the river. Stepmother would wash our clothes in the water, put them on the bushes. We hid, sat there, or played while we waited for them to dry. There was no cleanliness—just wet and dry. You take your garment, and you kill the lice in the seams.”

“I saw some foam on the edge of the river one time, and thought it was soap. Silly me, it wasn’t soap. There was no soap.”

_______________

By signing the Polish-Soviet Agreement in London on 30 July 1941, at the height of Hitler’s Operation Barbarossa, Polish Prime Minister General Władysław Sikorski gave the Poles incarcerated in the USSR a means to leave: Stalin had given permission for a Polish army to be formed on Russian soil. (For more details, see military timeline on this page.)

The poczta pantoflowa started filtering the news that there may be an escape for the Poles if they joined that new Polish army, whose enlistment stations quickly moved from southern Russia towards Tashkent, Uzbekistan.

In 1942, the Polish army organised the escape from the USSR of about 115,000 Polish civilians and soldiers—eight percent of the civilians on the four transport trains.

Stalin pushed Polish army commanders, headed by General Władysław Anders, to contribute Polish troops to the defence of Moscow, but the Polish commanders maintained their men were not yet trained, and refused to be drawn.

Those Poles eligible for the army also refused to leave without their families. Polish civilians disgorged from USSR forced-labour facilities and made their way to Polish army enlistment stations thousands of kilometres away by whatever means they could—on foot, dragging two-wheeled carts, on rafts down rivers and catching the occasional train, if it were available.

Most made their escape from the USSR through sea crossings south from Krasnovodsk to Pahlevi (now Bandar-e Anzali).

The Polish authorities knew Stalin could close his borders at any time and in 1942—from 24 March to 5 April and from 9 August to 1 September—they used cargo vessels already operating in the area to cram in all those Polish refugees who arrived at Krasnovodsk to get them out. Several orphanages took their charges over the mountains. It is not clear whether this was always the orphanages’ preferred route, or whether they deferred to it after the sea option closed.

In Persia, the Polish authorities sorted out the various groups of refugees: soldiers to training camps, most parents with children to civilian camps in Teheran and more than 2,500 Polish mostly orphans to Isfahan, where several large houses and institutions were donated for their temporary use. Isfahan became known as The City of Polish Children.

_______________

Whenever the news of the Polish army reached Maria Jarka in 1941, she still had a problem: Even if it had occurred to her to try to join the army, labouring on the frozen railway tracks had damaged her knee, and what would she do with her step-children?

With no money, no transport, and no food, the three would have remained in Kazakhstan had it not been for the American Red Cross setting up orphanages. Maria placed Jadwiga and Jan in the care of one in Pavlodar.

“She gave me an angora hat to put my plaits in. Just my fringe was showing. The boys’ hair had to be cut short for hygiene, but they were surprised because I came to the orphanage without nits. Whenever stepmother could get some kerosene, she would wash my hair, so it was clean. I never had nits.”

From small makeshift orphanages, Jadwiga and Jan moved to bigger and bigger ones as they travelled from Pavlodar to Ashkhabad (now Ashgabad) in Turkmen SSR (now Turkmenistan). They lost their ability to live together, because boys and girls were always housed separately, even in the same orphanage.

“I worried about Janek, but I couldn’t do anything about it.

“We stayed in a big building, about 300 of us, girls on one side, boys other side. The Russians arrested the manager and caregivers, and in the end there was one man from Ashkhabad, and one caregiver to look after us.2

“The man from Ashkhabad kept going to the office, to try and get us away. He kept begging the Russians to let us go “and there will be no more.” We were in groups, guides looked after the girls, scouts looked after the boys. We had the password for the gate. Finally, he came in the middle of the night and woke us up. Everybody was ready. The trucks came and took us. We were crying, praying, singing, because we were leaving Ashkhabad.

“It was a very winding dirt road, so the drivers had to have a little alcohol. Our driver took a wrong turning in the dust and had to reverse. As he was going backwards, I saw the precipice and screamed. The caregiver threw a blanket on me to stop me upsetting the younger children in the front of the bus.”

Those 300 or so Polish children and their caregivers were among the last to leave the USSR. In groups, they crossed Turkmen SSR’s precipitous southern border with Persia (now Iran) to reach first Meshed (now Mashhad), then Teheran. Shortly before the Stalin broke off diplomatic relations with Poland a second time—over Poland’s public contention that the Soviets had murdered the Polish officers in the Katyń region of western Russia— then Polish Ambassador to the USSR, Tadeusz Romer, apparently visited the Ashkhabad orphanage, and promised to get the children to Persia.

They were to be transferred into the care of a Mr Rudnicka at Teheran’s Camp 2. The last arrived in December 1943.3

An identity booklet issued to Jadwiga by the Polish delegation in Teheran shows that on 10 September 1943—a full year after Stalin closed the borders to Poles hoping to escape through Krasnovodsk (now Turkmenbashi) on the Caspian Sea—Jadwiga arrived at Starosta Obozu Uchodz Pol. No.2.4 By 12 September 1943, she was delivered to an orphanage in Isfahan.

Without this booklet, Jadwiga would not have known the route or the time it took for her and Jan to get from the Pavlodar orphanage in 1941 to their separate hostels in Isfahan in 1943.

Jadwiga’s identity book was more than just that. It instructed the children as to how they were expected to behave. It listed the pocket money issued to them. It listed what clothing the children received while at the Isfahan orphanage, and what they were issued in New Zealand.

Jadwiga translated the first points regarding behaviour, and pasted it in the front of the book:

“Remember, you are an ambassador of your country. Therefore your behaviour and speech should be excellent, do not tarnish your name—through this, opinion of Poles and Poland will be degraded.

“You are being helped. Help others, be courteous, strive high…”

Although in the end she could not prevent her hair from being cut, life in the Persian orphanages brought back to her some sense of limited order and routine. And even if she could not live with her brother, she knew he was in a similar house not too far away.

For the first time in years, the Polish children had more than one set of clothing. In Teheran, Jadwiga received two dresses, singlets, underwear and stockings, and a blouse, coat, cardigan, shoes, towel and a blanket. In Isfahan, she received a school uniform, and more clothes.

_______________

“We were in big orphanages—wealthy people’s homes. Instead of a fence, they had walls so high that in orphanage number nine, where I finally settled, they were to the level of the one-storey roof.”

These photographs were taken on 12 and 14 August 1944, shortly before Jadwiga, (Top: back, second from right. Right: back row, right) and her group left Persia for New Zealand. Part of a wall is visible in the background in the top photograph.

“Ours had a beautiful garden, and trees. We had three meals a day. It was like coming back to normal, even though we were limited by the high walls, and had to have police protection when we went shopping or to church once a month, because a lot of us were blonde, and they would snatch blondes.

“We had a little bit of freedom in Isfahan. The orphanage had a fruit garden, and an orchard. We used to hire bikes, and I learnt to ride. It was such a good feeling. I used to go with the older girls when they used to visit their brothers once a month. I’d go and see my young brother, and ride back through the orchard.”

According to isfahan city of polish children5 1,740 children from the Ashkabad orphanage went overland to Meshed, 675 of the youngest continuing to India and the remainder to camps in Teheran. The first Polish orphans arrived in Isfahan in April 1942 and by February 1943 the city housed 2,590 in 21 “establishments.”6 In September 1944, as more than 730 children and their 105 caregivers made their way to New Zealand, they left behind 1,152 other Polish children.7

Jadwiga and Jan learnt years later that the Russians would have “retained” their stepmother indefinitely had she not found an old Białystok utility bill in a pocket, and used it to prove her Polish connection.

_______________

Jadwiga remains grateful for New Zealand’s generosity in accepting her and her group of Polish orphans and caregivers.

“We came here with very minimal English, about a dozen words: ‘yes,’ ‘no,’ ‘thank you,’ ‘goodbye,’ ‘bread’ and that was about all. We couldn’t converse, which was hard. We went by train from Wellington to Pahiatua, and all the way, New Zealanders were waving to us. In Palmerston North, where they cool the engines and re-fuel, it was cordoned off and we saw all those people, and so many waving Polish flags.

“I thought, ‘Why are they so happy seeing me? Nobody was happy seeing us before. Why? They do not know me. I do not know them.’ The scouts, Kiwi boys, came to our wagon and gave me this pamiętnik [autograph book] and asked me to write something, my name. I wrote ‘Jarko’ because then I did not know how to spell it properly. Only after I started writing to my stepmother and she asked me, ‘Why are you using an “o” in your name?’ did I know how to spell my name correctly.

“From the train, we went into army trucks, and drove through Pahiatua township—just a little village, and perhaps half a dozen shops—and I see signs: ‘Pies’ Pies? [dog]. I said to the others, ‘Look there is a pies there.’ Perhaps the owner lives there and the dog is just there?

“And at the petrol station: ‘Europa.’ Europa? Where were we? What has this place got to do with Europe? All confusing in the beginning.

“The New Zealand people were so good to us. When they came to visit us in Pahiatua, they brought armfuls of things. We couldn’t wish for anything but—because our English was so limited—we couldn’t find the words to express our gratitude for their exceptional help.

“Whenever we have reunions we celebrate with a Mass and pray, forever thankful that New Zealand, with such a big heart, saved us. I still lack the words to express that gratefulness.”

Jadwiga, at her home in Orewa, wearing the Siberian Exiles Cross (Krzyż Zesłańców Sybiru).

Jadwiga received her Siberian Exiles Cross with Janek and others at a ceremony at the Dom Polski (Polish House) in Auckland on 27 March 2006. Established in 2003, the medal recognises Poles forcibly removed to Soviet forced-labour facilities between 1939 and 1956 and still alive in 2004. Polish President Lech Kaczyński signed the Legitymacja (the authorisation accompanying the medal).

Four years later, on 10 April 2010, President Kaczyński died with his wife and all 96 aboard the plane carrying them and many other Polish MPs, military personnel, and government officials, when it crashed on the approach to Smolensk airport in west Russia.

They were heading to the nearby Katyń memorial to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the 1940 massacre of 22,000 Polish officers—including Stanisław Jarka—by Stalin’s secret police, the NKVD.

© Barbara Scrivens, 2017.

Updated April 2021.

ALL BLACK AND WHITE AND SEPIA PHOTOGRAPHS COME FROM THE JARKA-COOPER COLLECTION. MICHAEL JARKA TOOK THE SPACEROWA HOUSE PHOTOGRAPH AND BARBARA SCRIVENS THE LAST ONE.

THANKS TO THE NORTH AUCKLAND RESEARCH CENTRE IN THE TAKAPUNA LIBRARY FOR THE LOAN OF AUDIO RECORDING EQUIPMENT.

ENDNOTES:

- 1 - On 9 April 2021, five years after I first interviewed Pani Jadzia, she did not pause when filmmaker Warren Elliot asked her to recite the verses for his camera.

- 2 - Krystyna Skwarko, wrote in The Invited , section 15, about a Mr Orlowski. Pani Jadzia’s

“man from Ashkhabad” and Mr Orlowski may have been the same person. All the adult caregivers had been arrested by

the Russians, and older children took their places, so no wonder Pani Jadzia felt their dearth.

The Invited was published in 1974 by Millwood Press, Wellington. - 3 - Ibid.

- 4 - Could this have been the full name of their destination camp?

- 5 - Editors, Irena Beaupré-Stankiewicz, Danuta Waszczuk-Kamieniecka and Jadwiga Lewicka-Howells, OBE, Association of Former Pupils of Schools, Isfahan and Lebanon. Isfahan, City of Polish Children, 1989, page 123, ISBN 0 9512550 1 2.

- 6 - Ibid, page 126.

- 7 - Ibid, page 127. Note, the book’s total of 836 differs from the actual 838 who arrived in New Zealand.