Nasza Chatyna

Autor nieznany

Cicho, ciepło i tak miło

w tej naszej chatynie.

Śnieg o małe szybki bije,

świszczy wiatr w kominie.

Słychać jako w polu szumi

wicher w skarg użaleń.

Nam zacisznie w izbie naszej

i nie smutno wcale.

Mama szyje, rychło już

będzie dla mnie sukienka.

Babcia przędzie,

Nitka Iniana, cienka.

Jasio jeszcze nie śpi,

Tatuś czyta mu elementarza,

a Jaś mały, ośmiolatek

ABC powtarza.

I Basieńka jeszcze nie śpi.

Zwolna ją kołyszę.

Płatki śniegu biją w szyby,

wicher mąci ciszę.

Niech tam sobie śnieżek pada,

niech wiatr szumi w dworze.

Gdzież nam lepiej jako w Polskim domu?

Gdzie być lepiej może?

Henryka Aulich Blackler

Henia Aulich Blackler started talking to the tape before I was ready. Her quiet voice made me throw out the rules about introducing the subject.

She spoke about witnessing the German bombers as they cut through Poland during their September 1939 invasion, and again as they re-invaded on 22 June 1941.

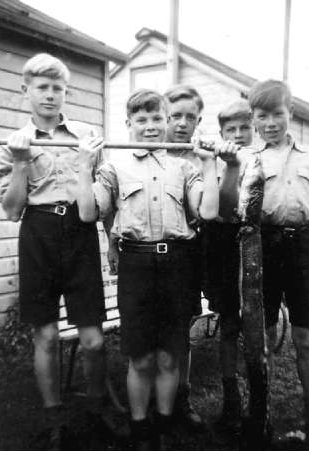

She peppered her English with Polish words, several of which I have retained. They grew fewer as her mind travelled from her home in central Poland to captivity in the USSR, freedom in Persia and, finally, refuge in Pahiatua, New Zealand, where she posed for this photograph in 1945.

Henia arrived in New Zealand on 1 November 1944 with three of her brothers, 699 other Polish children and their 105 caregivers. The New Zealand government converted a former prison for “enemy aliens” in Pahiatua, central Manawatu, into a temporary shelter for the Polish refugees, and extended its invitation after Poland’s apparent allies gifted the country to a post-war Soviet-controlled government.

It has been a pleasure meeting and spending time with Pani Henia at her home in Christchurch. I thank her for her grace and her patience.

—Basia Scrivens

SONGS OF RESILIENCE

by Barbara Scrivens

The September 1939 school day started the same as any other for eight-year-old Henryka (Henia) Aulich. Then the headmaster strode into her classroom and spoke to the 30 or so pupils.

“Children, take all your things from your desks and go home straight away. You are not to go to play with any of your friends, or visit anyone. Go straight home.”

Like the other pupils at the Kupiski school, the Aulich siblings obeyed but, at first, did not give too much thought to their instructions.

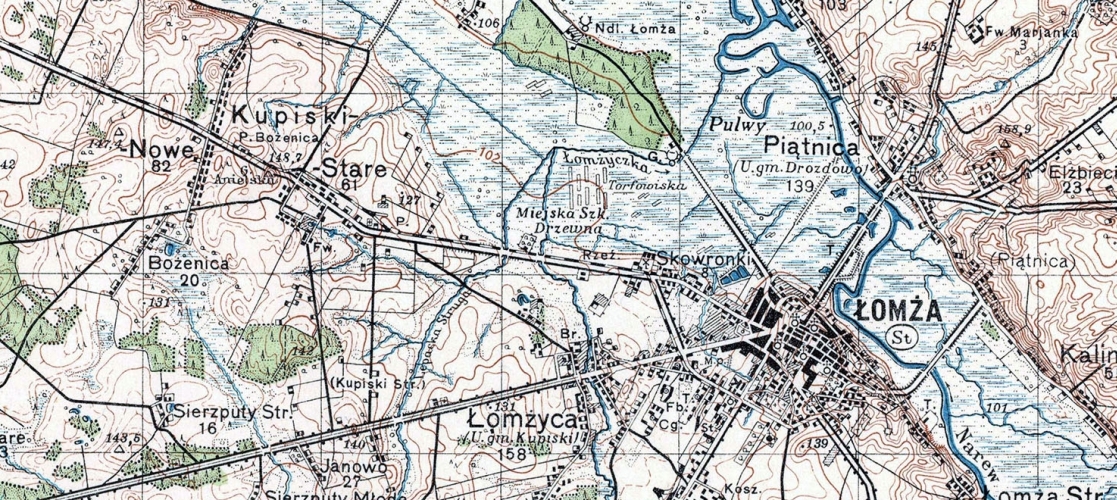

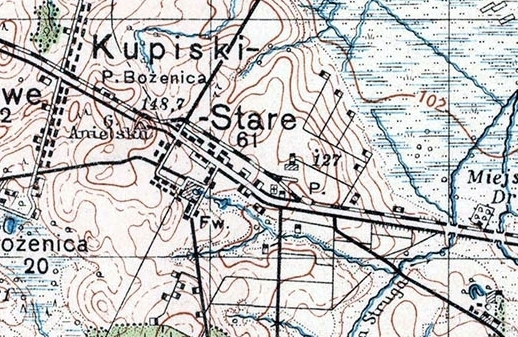

This 1931 map of Łomża and environs, including Kupiski, is part of a series drawn by the Wojskowy Instytut Geograficzny, Warszawa (Military Geographical Institute, Warsaw).1

Henia's school lay between Kupiski Stare and Kupiski Nowe, and was named after the nearby Góra Anielska (angel’s hill, seen in the top left-hand side), itself named thanks to a fable of bells that apparently once rang without human help at 12 noon and 12 midnight. The Aulich farmlet lay towards the road to Łomża, off the map on the right.2

Henia: “We were half way home when we heard a terrible, terrible noise. We didn’t know what it was because the szosa, the road that we were walking on, was covered by trees, Polish trees that grew on each side to stop the tar mixture melting when it was hot.

“We looked up, because that noise was getting closer and closer, and we saw this mass, a mass of this black, what looked like birds, because I’d never seen an aeroplane before.

“We were very frightened. We ran. And then the aeroplanes passed over us, over the trees, and we heard the bang, bang, bang. It was the Germans, the invasion, dropping bombs on Łomża. We lived on a hill so we could see—picture perfect—the fires, and Łomża going into smoke.

“For three days, day and night, they came with these samoloty [aeroplanes], flying over us, and bombing Łomża.

“Because we lived on the main road, it was not safe for us to be home. On the second day, we put all our things on our cow, Zelma her name was, and hid in the forest. Sometimes the planes went away and we thought they had finished, but next thing, we heard the roar again.

“When it was all quiet, we returned home. There were fires still burning in Łomża, but no samoloty. Then we saw the Germans coming along the road with their beautiful new tanks and horses and shiny kitchens, glistening in the sun. We were such country bumpkins, we had never seen anything like it before. The whole day, they came into Łomża.3

“They lodged themselves by the river [Narew]. I didn’t see them. Mum told us about it. When they wanted food, they grabbed anybody’s cows from the pastures and killed them, and fed the soldiers.

“There were quite a few days of quiet and Mum said, ‘I think it will be all right.’ And we took the cow to pasture by the wee stream. Not only us, there were other children as well—about 10 of us—and next thing, we heard planes again. Just two appeared in the sky, and they started to machine-gun us. We flung ourselves on the grass, to pretend we were dead.

“They must have seen us, or perhaps they recognised that we were children. Mum never let us go again with the cow. I can still remember those planes. I dreamt about them afterwards, dreadful nightmares.

“At night there was sometimes a knocking on the door: Polish soldiers asking for bread or food, men who were getting away after the army was rozproszone [dispersed], trying to get back to their homes, I suppose. We saw them retreating.

“After all was quiet, Father said he wanted to go to town to see what had happened. He restored furniture, anything that was broken or needed doing up. He restored the furniture in the cathedral, and made beautiful things. The churches here are nothing compared with what I remember in Poland. I think that after the bombing he was worried about the cathedral.

“He saw German soldiers throwing grenades in the Jewish shops. The Germans captured him and put him in a prison, like an obóz [camp], where they kept the Polish people. Neighbours who escaped came to tell Mum.

“It was dreadful. For perhaps one or two weeks—I didn’t register the time—the Germans stayed in Łomża, and there was no shelling, nothing going on.

“We sat on this little hill and looked at the German soldiers through the slats in the fence. Sometimes they threw lollies to us but Mum said not to pick them up because they could be poisonous. Then, all of a sudden, they left. And again, there was nothing.

“Next thing, we heard the noise again. Not the same noise as the samoloty, or the strzelanie [shooting] between the Polish and the German soldiers. It was the clattering of Russian tanks heading into Łomża. The Russians just moved in. They didn’t liberate Poland. They just moved into Poland.

“After that, it’s not so clear. I heard Mum speaking—not to me because I was the minor—to my older sisters.

“When the Russians came, the first things that disappeared were the holy pictures in school. We were not allowed to put any crucifixes or any Blessed Mother’s or Blessed Father’s pictures on the walls, or say prayers, or anything like that.

“Mum went into town, sometimes at two o’clock in the morning, to buy things we needed, like meat. She had to walk, because we didn’t have a car or anything like that. She always came home crying and with practically nothing, because the people from the town were immediately there and could stand in the queues and get the first bit of whatever they were selling. By the time Mum got there, there was not much left.

“Luckily we had vegetables because we had a big ogród [garden]. We fed ourselves from that. We never brought any potatoes or carrots or apples or pears because we had all these things, and chickens and a cow and a few pigs, and Mum always made our own bread.”

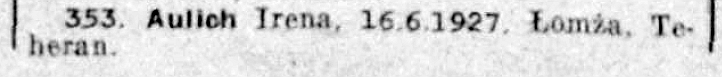

Henryk Aulich poses in one of Łomża’s strolling gardens circa 1937 with, from left, Antoni (born 23 October 1934), Piotr (born 29 June 1933), Józef (born 27 June 1932) and Irena (born 16 June 1927).

_______________

“My First Holy Communion at the cathedral, just before the war, was a beautiful day. For the first time in my life, we went to see my mother’s sister. She lived right next to the river, and it was the first time I saw so much water. There were boats and so many people walking on the promenade. I thought it was wonderful. Father took us to a shop, and that was the first time I had ice-cream.

“We couldn’t go to Mass every Sunday, because of the distance and what Mum had to do, looking after eight children.

“My father also made furniture in his warsztat [workshop] at home. When he worked at the cathedral, he left home when it was still dark, and came back when we were in bed. Sunday was the only day that we saw him, because in Poland in those days there was not a Saturday off, as it was here when we arrived. Sunday was the only day of rest. He was always engrossed in his trees. He loved the apple trees and the pears, the cherries and all sorts of other things we had in the garden, strawberries, raspberries and our gooseberries.

“My sister Marysia told me that that when he came in on Sundays, he would take us on his knees and sing to us. That’s where I got my love of singing. I would have loved to have taken singing and piano lessons but I never had the chance.”

_______________

Henia, named after her father, has documentation to show that her paternal grandfather, Franz, came from Strauszdórfel, in Śłąsk (Silesia) and that her grandmother was Agnieszka, née Liechler.

Their son, Henryk Aulich, born 1898, married Waleria Narewska in the Cathedral of St Michael the Archangel, Łomża on 13 September 1920. Waleria was born on 22 September 1903. Her father was Stanisław and her mother, Rosalia (née Bogus).

Henryk’s and Waleria’s first two children died. Next came Marysia, Elżbieta, Irena and Henia, born on 28 December 1930. Four boys followed: Józef, Piotr, Antoni and another Henryk.

Henryk and Waleria with Marysia and Elżbieta, circa 1927.

Waleria and her children lived uneasily during the Russians’ on-going occupation of Łomża, their worry sharpened by Henryk’s absence, and stories of families disappearing overnight. Their school eventually re-opened and the Aulich siblings again walked back and forth along the road with the overhanging trees, past Kupiski Stare’s houses, and a hall that Henia remembered for its concerts and a poem that she recited there, nasza chatyna, the same one she recited at a 70th reunion of Pahiatua children.

In June 1941, while Marysia Aulich was living with an aunt in Ostrołęka, the rest of her family became one of those that Soviet soldiers rounded up overnight.

Henia: “We heard the dog barking and next thing, an explosion. They killed the dog. They killed our dog, and started banging at the doors and windows. They had bayonets and told us to get up and get dressed and that we’re ‘going to beautiful Russia.’

“They wouldn’t let Mum take anything, no bread, or anything. Perhaps it was because there were so many children to dress and organise, because it was dark and we were all still in bed. They said, ‘You’ll have everything in Russia.’

“The train stood on the [Łomża] station for two or three days while they packed us in, bringing in, and shoving people into the carriages. One is full; they filled the next one. We just had to wait.

“I used to ask: ‘Why us? We were so many children and a single mother.’ They [Soviet soldiers] rounded up most of the people who worked at the urząd [council], and who they thought had any connection with Germans, or any other country, but our father was captured by the Germans—he didn’t work for them.

“We were the last transport from Poland.4 From the train we saw the bombs dropping and knew it was the Germans invading Poland again. It was semi-darkness but we could see the bombs and people dying not far from us.

“They said it was a miracle that the bombs didn’t hit the train directly because it was so long and huge, and only wooden carriages. An older person died from a heart attack, but only about two or three people died from the shrapnel, the debris that scattered all over us.

“But even before, those two or three days that we stood at the railway station, we were already dying from hunger, because the Russian soldiers wouldn’t let us take anything from home, or give us anything.”

Their neighbours’ children alerted others to the Aulichs’ absence from school. The neighbours went to the railway station, found the missing family, and returned with a loaf of bread. Waleria found some rope, which she put through one of the two tiny windows high up in the wagon. Outside, her neighbours concocted a way for her to haul up the bread.

The smuggled food did not keep Henia and her younger brothers from crying.

“We were hungry and frightened. Mum wrapped me up in a sort of shawl, and sneaked in a little prayer book. She opened it up at a picture of a guardian angel, and said, ‘Henia, don’t cry. Look at this angel, and she will look after you.’

“And from then on, I can’t remember crying, or begging Mum for something to eat, because I knew there was nothing—not then, and not in Russia.”

The strafing German warplanes occupying Henia’s nightmares were replaced by the new trauma.

A few weeks before Soviet soldiers forced her and her children from their home, Waleria Aulich organised this studio photograph. Piotr (Peter) told Henia that they dressed in their “Sunday best.” Clockwise from left: Henia, Elżbieta, Piotr, Józef, Irena and Antoni. Henryk is in the middle. Their sister Marysia had already left to live with an aunt and find work in Ostrołęka. Henia wore the same dress to Russia.

_______________

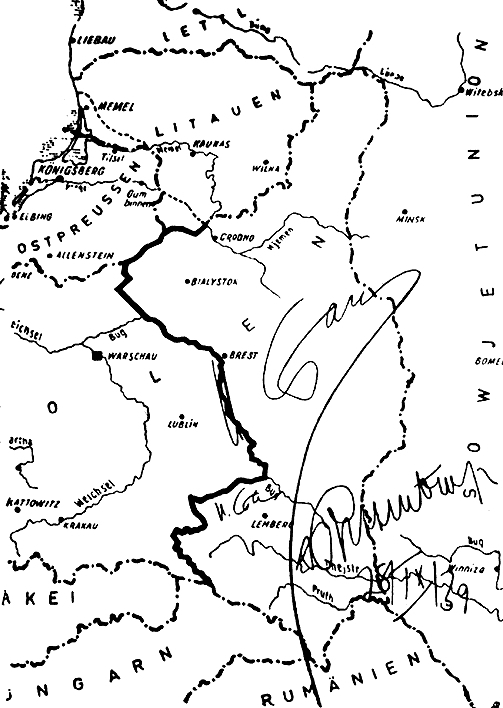

The map below shows Stalin and von Ribbentrop’s signatures, dated 28 September 1939, confirming the division of Poland, concocted in a non-aggression pact between Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia, and first signed on 23 August 1939 by the two countries’ foreign ministers, Joachim von Ribbentrop and Vyacheslav Molotov.

Łomża, 150 kilometres north-northeast of Warsaw and 80 kilometres west of Białystok, lay just within the Soviet side and was among the first Polish cities to suffer Germany’s re-invasion.

Stalin’s and Von Ribbentrop’s signatures on the German-Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Demarcation document, dated 28 September 1939. Łomża is 80 kilometres west of Białystok and 150 kilometres east of Allenstein (Olsztyn).5

Once the Soviets had occupied eastern Poland, that German-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact and Treaty of Friendship did not seem extend to their accepting any apparent German collusion on behalf of the Poles within their sphere.

From the time the Soviets invaded Poland on 17 September 1939, the NKVD,6 Stalin’s secret police, accumulated records of “anti-Soviet elements”7 among the Poles. Henryk Aulich’s capture by the Germans made his immediate family’s forced-removal to the USSR inevitable. Soviet rule had always been clear that a person’s family was as much to blame for any alleged misdemeanour or perceived transgression as that person, and that person’s innocence had no bearing on the decision.

Aleksander Gurjanow collated records of cattle trains that transported Poles to NKVD forced-labour facilities in the USSR.8 Three mass forced-removals of hundreds of thousands of Polish citizens occurred in February, April and June 1940. Soviet soldiers had strict instructions on how to approach the Poles in their homes and farms—generally at night—round them up at gunpoint, escort them to train stations, bundle them onto wagons previously used to carry cattle, and escort those trains to thousands of forced-labour facilities throughout the USSR.

Hitler’s invasion of Soviet-occupied Poland on 22 July 1941 stopped another spate of mass forced-removal of Poles by the NKVD, started barely a week earlier.

Twenty-two trains carried ‘only’ 25,039 Polish citizens to the USSR from 13 June 1941. Fifteen of the 22 trains left before 21 June 1941.

Six of the trains—carrying 7,511 people including 1,175 from Łomża—do not have recorded departure dates, but judging from Henia’s experience, they must have travelled ahead of the German army’s push towards Moscow. Two of the undated trains, carrying 76 and 311 people, reflect outliers to the NKVD’s usual meticulous removal of well-more than a thousand at a time. The last recorded train left Tułska on 5 July 1941.

Apart from the train that languished at the Łomża station with the Aulichs, and one that left Hajnówka, south of Białystok, on 19 June 1941, the balance left from places far closer to the then Polish-USSR border.

The Łomża train was scheduled to arrive in Aktiubinsk (Aktobe), Kazakhstan, 3,000 kilometres away.

_______________

“It was night-time when we arrived at this little place. The sky was pitch-dark, and there were millions of stars. It was as if you could lift up your hand and touch one. As tired as we were, we couldn’t believe our eyes.

“Someone… gave me a bucket to get some soup, but it was just water with one potato, floating.”

“The Russian soldiers put us on little carts driven by camels, took us to a place, and shoved us in. We slept like sardines, and in the morning, before it was even light, they took all the able bodies to the fields to harvest the wheat.

“They left me with my brothers. My other two sisters went with Mum to pick up every head of wheat they could possibly find, because that’s what we were there for. All their men were in the war and they had to have someone to harvest the produce, to feed the country.

“Someone told me to go to canteen, gave me a bucket to get some soup, but it was just water with one potato, floating.

“By then I was 11, going on 12. My youngest brother was only two years old. I didn’t know what I was doing. Most of the time, I was sick, my sister Elżbieta too. She had typhus.

“It was a wilderness; no trees, just the steppes. We lived in huts of home-made clay bricks with a bit of a roof.

“There were two extremes of weather. There was heat, immense heat. Mum used to have blisters all over her back, because of all the bending down, picking up the wheat heads from the ground.

“The local people had fires inside their huts in the winter, but in the heat, they had little fires outside for cooking. They burnt dung that was almost dry, mixed with earth, straw and old grass. The Russian women used to put the milk to sit outside, to make kwaśne mleko [sour milk or buttermilk].

“He was after my brother, and he had that sickle, that Russian sickle.”

“I heard screams and rushed outside and saw my brother Antoni running around. After him came this man, like a giant, with this sickle. I didn’t know what to do. I left my three other brothers behind—in the panic, you lose all reason and control, you just want to get away from what you see is imminent. I grabbed my brother, and we ran, and ran, and ran.

“My brother was so hungry, he had put his finger in some kwaśne mleko and started licking it. The man came out of his hut and Oh! He was after my brother, and he had that sickle, that Russian sickle. He was going to chop him to bits.

“He was a huge, big man. Antek was maybe seven. We screamed and cried and followed the grooves. You see, they took the workers to the fields in those camel-driven buggies—the same ones the soldiers put us on when we got there—with big wheels and wooden boards to sit on. They make grooves in the ground, and we followed the tracks as much as we could. Then we heard harvesting machinery, and we prayed and hoped that Mum would be there.

“The man stopped when we were quite far from him. Just stopped. He must have heard the harvesting machines—the authorities—and didn’t chase us after that. We were so distraught, Mum went to talk to the official and they allowed us to live there, on the side, where the harvesting was. Antek and I never went back to the other hut, but Mum went to get my brothers.

“They built us an igloo from straw and we slept in there. It was tight, but at least we were close to Mum. It had a sort of tap, for the animals, that we used.

“It was so cosy that when we arrived in New Zealand, my brother would quite often disappear at night. The farmer from a few doors along complained that there was a boy sleeping in the straw. My other brothers knew, and eventually someone told me, but what could I do?

“… he was just looking for shelter, the same as when they built us that straw igloo where we were safe.”

“Antek was having nightmares but nobody understood. They just thought he was a naughty, bad boy but he was just looking for shelter, the same as when they built us that straw igloo where we were safe. Still starving, but at least we were together as a family.”

In Kazakhstan: “The night the harvesting was over, they took us out. The seasons changed that quickly, in no time, it snowed.

“Mum went to quite a few people and, just like Joseph and Mary when they looked for a place for Jesus to be born and couldn’t find any, Mum struggled. She found us a shared place with a hole in the roof. One night there was so much snow that, when we woke up, our legs were covered and we had to dig ourselves out. We stayed there for quite a while.

“Mum heard of Polish people in the next town where there was a railway. My brother Peter [Piotr] said it was Dżurudźn. We got a lift from a man who was transporting wheat to the town on a sled. There was no road, and he didn’t secure the bags of wheat. He turned the corner, the sacks of wheat slid off into the river with our gear, and tipped off all the people. We had to walk the rest of the way to that town. We were so tired by the time we got there, because we walked for half a day.

“We found some medical help, and some Polish people. They organised a place in a building for the children so they wouldn’t be alone and I remember going a couple of times. Apparently, there were many transports going through that town, Polish men going to fight the Germans.”

_______________

Hitler’s initial swift assault into Russia led to Stalin’s starting to court the Allies, including—for a short time—Poland. On 30 July 1941, Polish Prime Minister Władysław Sikorski and Soviet Ambassador to the United Kingdom Ivan Maisky signed an agreement resuming diplomatic relations. The Soviet government agreed to the formation of a Polish army on its territory and granted “amnesty to all Polish citizens now detained either as prisoners or on other sufficient grounds.” (See military timeline for the full English version.)

“… Mum threw her arms around us all—five of us—and we got into that carriage.”

In theory, this meant that the Aulichs and others in their June 1941 transport should have spent a matter of weeks in forced-labour. However, as Henia said, the Soviets needed the Poles to help with the harvest. The family’s experience of extremes of seasons points not to weeks, but months, in Kazakhstan. Their haphazard release after the harvest suggests that the impoverished local community quickly eased out then-superfluous people.

Without her husband, or enlistment-aged sons, Waleria and her children were vulnerable. The ‘amnesty’ referred to Poles able to join the new Polish army. Józef, nine in 1941, was too young even for the army’s military cadet wing, set up for teenagers.

“Apparently, the Polish people gathered near us decided that, because Mum couldn’t feed us, and because we were always sick, we should go on the train with the other children in the orphanage.

“I had dysentery and yellow jaundice. I didn’t register what was going on. I know we went to the station, Mum threw her arms around us all—five of us—and we got into that carriage. It was full of men, ready to join the army, but not in uniform. We were allowed to sit quietly between the seats.

“Mum was left with Elżbieta and Heniek, the oldest and the youngest. It was easier for her then because she only had three mouths to feed instead of eight. With that amnestia [amnesty], they travelled from one place to another until they got back to Poland. Sometimes when they had money, they caught a train.

“When they arrived back in Kupiski, the house was gone. Not bombed or burnt, just taken. People took it to bits because it was a beautiful wooden house. Dad built it just before the war, and all the meble [furniture]. Everything was gone.

“I’m not angry about it. It was war, and there was bieda [poverty] in Poland. Some people in our village didn’t even have a wooden floor. They had clay floors with thatched rooves, not like the house we had.

“After the war, Mum found out that Father had been taken to a concentration camp.”

_______________

“We nearly got left behind in Russia because we were so tired when we stopped, we went to sleep.”

“How long we were in that train with the Polish men, I’ve got no idea. In the end, we stopped somewhere in the never-nevers, fields and nothing else. Somebody said to us, ‘Walk behind us,’ and we were just like a sznurek [string]—Irena, my brothers and I—walking for the whole afternoon, until they said, ‘You’re all right now. You are over the border.’

“We nearly got left behind in Russia because we were so tired when we stopped, we went to sleep. We sat right there on the ground and slept. There seemed to be so many people around us. A man woke us up and said, ‘Who are you?’ and we said we were Aulich. ‘You should have been on the ship already… You’re practically first on the list… Didn’t you hear your name?’

“That was another miracle, as far as I’m concerned, because on that trip, there were so many people, the first ones called went right to the bottom of the ship: they packed them everywhere. Because we were last, we were on the top, on the deck and the fresh air. People underneath didn’t have fresh air, and a lot got very sick, and I think a few of them died. We heard they threw them overboard.

“We were so relieved when we were on that ship, we slept again, and didn’t worry about anything. We crossed the Caspian Sea, the last time we were together as one family unit.”

_______________

More than 30,000 Polish soldiers and civilians arrived in Pahlevi (now Bandar-e Anzali, Iran) between 25 March and 5 April 1942.9 A second evacuation of Poles from the USSR remained in “considerable doubt” but between 10 August and 2 September 1942, another 69,247 Poles arrived in Pahlevi, on 26 crossings from Krasnodovsk. The last vessel included “Krasnovodsk Staff,” suggesting the Polish army could no longer help any other Poles still left in the USSR.10

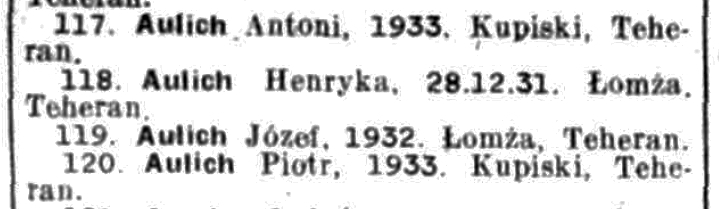

The Aulich siblings’ names appeared on page 1 of List 1 of “Osoby Wyewakuowane z ZSSR” (People Evacuated from the USSR).11 The list does not differentiate between those who arrived on the first or the second transports across the Caspian Sea. Henia’s and Antoni’s birth years were incorrectly recorded.

“We got to Pahlevi and spent the night in a make-shift shelter, the roof made out of canvas, and on sticks. There were blankets lying on the floor and we were so tired, we went to sleep. Very early in the morning, my uncle came, my mother’s brother. He was one of the soldiers helping with the children and had seen our name. He said, ‘You’ll be all right. In the morning, before you go to the baths, I’ll come to see you again.’

“He never came because that same night, he had orders to go to Egypt. I never saw him again. He died in the war.

“They put us through the showers, and shaved our heads and threw away our clothes because of lice. I had a dress, some sort of frock, with a bit of safety pin to keep it together, because it was torn from my waist down. You could see it on the floor, crawling with lice. They gave us a pair of shorts and a singlet. Whether you were a boy or girl, it was the same.

“I was so sick; I walked like an automatic creature. They had us like sheep going this way or that way, and we were looked after by doctors or nurses—or whatever they were—in uniforms. They asked us a few questions and separated me from my brothers and my sister because I was sick, and they took the sick ones to what they called the English camp. It was right on the sea and all tents. They made us go to the sea and sit in the water, on the edge, and they fed us raw eggs and other healthy food to help us get our strength back. The boys buried their eggs in the hot sand to get them a bit set. I don’t know how many weeks we were there, two or three, then we joined the rest.

“They put us in trucks and took us to Teheran—great big buildings and hundreds and hundreds of people. We slept on the floors, on blankets, and got interviewed by Polish ladies and gentlemen. Before, they looked at our health rather than family-oriented things. In Teheran, they asked how we got there and who was with us.

“I said I came with my sister and my brothers, and I asked, ‘Where are they?’ My brothers were in number one camp and my sister was in number five. They took me to my sister, and it was so wonderful to see her. Then, we were allowed to go with a teacher to meet my brothers. We didn’t stay in Teheran long. We were shifted to Isfahan, still separated: the boys were in boys’ houses and I was with Irena for a while.

“She was one of the girls who learnt how to make rugs—I have a tape of when they presented the Shah of Persia with the rug that they made. Because she was older, she was more free and allowed to go to the pictures and socialise. She met an Armenian Persian who ran the cinema, and she married him.

“She was on the list to come to New Zealand. She came to me and she said, ‘I’m not going with you because I’m going to have a baby, and I’m marrying Hetcho.’ I think something like Davidian was the surname. It is written that 733 children arrived, but not really, because my sister didn’t come.”

Prime Minister Peter Fraser invited the Polish children and their 105 caregivers to live out the rest of the war in New Zealand. It is not clear whether that invitation stated exact numbers but the government reorganised a former internment camp used from January 1943 to detain 185 mostly Japanese and German civilians, then classed as “enemy aliens.”12 Building materials came from military camps throughout New Zealand, and army personnel built extra dormitories, classrooms and dining rooms. The “enemy aliens” returned to Soames Island in Wellington. (For more on the Pahiatua camp and the introduction of the children to New Zealand, see blue skies, green grass and warmth.)

_______________

“New Zealand was wonderful—so much green and colourful little houses on the [Wellington] hills, and no worry. Everybody was waving to us, and it was like heaven, like going into a raj [paradise].

“It was wonderful, but not always wonderful. Some had it better in the camp than others. Some of the older girls were more outgoing. One is not the same as the other, in spirit and in odwagi [courage], bravado.

“I always loved dancing and singing. My sisters always sang and before the war, Father got a gramophone and a record, and we danced to it. My sisters taught me the steps, more or less, and when we started to have films in the hall in Pahiatua, when we came back to our dormitory, the girls said, ‘Come on, Henia, you can dance the same as those girls.’ Most of the films were innocent pictures with singing and dancing. I learnt a lot from them because who else was there to teach us? Who was there to kiss us goodnight, or any of those things?

“Many times I got myself into trouble because of my singing and dancing. We always had a teacher sleeping in the middle of the barrack, in a room to herself, and sometimes she’d be out after curfew, so the girls would whisper, ‘Come on Henia, sing us a song.’ I couldn’t resist. I loved singing, so I would burst out in song, or perform like some kind of Betty Grable… Next thing, the teacher would come in and say, ‘Cleaning the toilets for a whole week!’

“When I had my first period, I went to the teacher, and she gave me a packet of pads. She didn’t explain what it was all about, or anything. She just put me on the list that I had the job when my name came up, to take these pads to the drum to be burnt. I learnt what life was about from different girls, most of them older girls, and from my peers.

“Although we were all together in Pahiatua, we all had different upbringings and had different struggles in Russia. We had been traumatised by different things, and never recuperated. We did our own chores, and kept our feelings to ourselves.

“We did have the opportunity to be in films, and I loved that, and singing lifted us all because we could do it together. That was the best time in Pahiatua.”

The group that donned kilts and danced a Scottish jig for New Zealand Prime Minister Peter Fraser on 26 November 1945: From left, Zosia Iwan, Helena Rombel, Czesia Bełczącka, Ludka Bartniczak and Henia.

Once the war in Europe ended, and it became clear that the Poles had not gained a free country, the children’s guardians in New Zealand started integrating them into local society. The Catholic Church arranged for parishioners to host Polish children during holidays, and the government arranged English teachers. Then, Pahiatua did not have a local high school and children reaching that age had already started to attend boarding schools or had been fostered out, and enrolled in high schools throughout New Zealand.

_______________

“About 20 of us went to Sacred Heart College, Christchurch. They lined us up and the sister said, ‘These 10 are going to be staying here, and you 10 are going to St Mary’s, and be looked after by foster families.’

“I was taken to a Mrs Ormandy. She was a lovely lady and had a daughter, who worked in Wellington, and who stayed with her sometimes. But the fact was, outside camp everything was foreign to me. Mrs Ormandy had to teach me the roads and where to go. At first I walked to school; then I biked.

“At St Mary’s School, we learnt English practically, and they gave us a wee bit of leniency with the words, but Mrs Ormondy was from the Polish family of Kiesanowskis from Marshlands Road, and when I got home from school, she talked to me in Polish. She thought she was good, talking to me in Polish. As much as I loved it, of course, it was not doing me any good, because I didn’t learn English like the others who had to talk English at home.

“I was at St Mary’s perhaps a year, but I still graduated, and got my diploma with 75 percent in shorthand typing. I was quite happy with that. I was allotted to go to Villa Maria College [Riccarton, Christchurch]. After the infantile paralysis [polio] outbreak,13 we went back to camp for the holidays. When I returned to Christchurch, I got a letter from the camp officials to say that I’m to go to Teschemakers College in Oamaru.

“I didn’t want to go. I didn’t know anybody there, and for the first time in my life, I let my feelings known: I wasn’t happy. One of the girls from Villa Maria, Joan McLellan, befriended me and said, ‘Mum and Dad will probably take you. I’m only one child.’ So that was agreed.”

Henia at Villa Maria College in 1947. Green and Hahn Photography in Christchurch took the image.

Henia, sitting in front, in her element centre stage, taking part in one of the Villa Maria College concerts. Frank McGregor took this photograph. His studios were then in Armagh Street, Christchurch.

“When I was at school in Villa Maria, one of the sisters said, ‘I hear your brothers are going to Poland.’ I said, ‘I can’t think why. Nobody told me.’ The days passed and next thing I knew, Peter and Joseph [Józef] were in school in St Bede’s College [Christchurch] and staying with Mr and Mrs Newman in Jeffreys Road. I was allowed to go there to meet them.

“Antek never went to a New Zealand school. He was always in the camp. What happened later was apparently because of his silly running away from the camp, and going to sleep in people’s barns. He wasn’t happy. All he wanted to do was sing and be lovely to everybody, but nobody took much notice of him.

Antoni Aulich, far right, in 1947, with a group of friends and the eel they caught in the Mangatainoka stream that ran near the Pahiatua camp. The other boys are, from left, Bolesław Banasiak, Piotr Mazur, Stanisław Dygas and Władysław Nowak.14

“Peter and Joseph loved St Bede’s, and loved the people they were staying with. Peter apparently said to the brother that he admired him so much, he wanted to be a priest. They were delighted. But when we went back to camp for Christmas, it was the first time we girls were allowed to dance with the boys. We were actually allowed to go and talk to the boys of the camp, and dance with them. A lady from Pahiatua played the piano for us.

“Antek said, ‘They’re telling us in the camp that we have to build up Poland. We have to go.’”

“Peter thought, ‘This is nice,’ and decided he did not want to be a priest after all. When he went back to St Bede’s College and told them, he reckoned the situation changed.

“Back in the camp in the holidays there was some sort of disagreement between Peter and the son of a man who looked after the boys. I didn’t know anything about it then, but some people told me about it at a Pahiatua reunion years later: When Mum found us through the Red Cross, one of the teachers wrote her a letter to say, ‘You must take your children from New Zealand because if you don’t, you will never see them again.’

“And Mum had nothing. Nothing. She had to be resettled herself. When she got back to Poland, she and my sister and brother lived with our neighbours for a while, then Mum got the authorities to say that she had no house to live in. They found her a place on the other side of Poland, in Lubawka, close to the Czechoslovakian border.

“When I went to Poland in 1986, they showed this place to me. It was a piwnica [basement], dreadful.

“Joseph didn’t want to go back to Poland. He said, ‘No, we’ve had enough of this shifting from here to there. We are quite happy in New Zealand.’

“Antek said, ‘They’re telling us in the camp that we have to build up Poland. We have to go.’

“I was in the camp when they left. There were some sort of holidays and they let me stay a couple of days longer. The day my brothers left, I thought how ridiculous it was that all they had amongst the three of them was a tiny, bedraggled, little bag of clothes.”

_______________

In the book new zealand’s first refugees, pahiatua’s polish children,15 Peter Aulich wrote an account of the brothers’ return to Poland in November 1948.

“… They gave us rusted mess tins into which they poured, or rather ladled, thick macaroni tubes…”

“On one hand, there was the joy that we were back in our homeland. On the other hand, disillusionment at the poverty and lack of freedom—at whose restriction we were soon made aware, because Poland was now under Soviet communist occupation.

“We were forbidden to photograph anything or have contact with our kin, who were kept far away from our ship.”

Peter described their trip on the ms batory to Gdynia, where they received 500 złoty at the repatriation office. Their feelings of wealth evaporated as soon as they tried to buy something, and saw that the “cheapest and smallest box of chocolates” cost 730 złoty.

“While waiting in a queue at the station in Gdynia before the train departed, we were invited for a meal. I will not forget this meal to my dying days. They gave us rusted mess tins into which they poured, or rather ladled, thick macaroni tubes. When I tasted it, I immediately realised the meaning of the warning not to return to Poland given to us by our guardian, a religious monk and a teacher in Xavier College, [St Bede’s] Christchurch. But it was too late for sorrow or grief.”16

Henia: “On the boat through the Suez Canal, they ran into quite a few Polish people, and started hearing stories about Poland after the war, and the Iron Curtain. All of a sudden, they knew that they made a mistake, but it was too late.

“They returned to Poland in practically the same state as when they left for Russia [in 1941]. And Mum then had six people to feed, and all from coupons…

“My sister Elizabeth told me in ’86 that Mum was fading, and asked if I could visit. ‘Mum often talks about you,’ she said. There was nothing physically wrong with her—she just gave up living.

“We borrowed money from the bank and I went to Poland with my daughter, Christine. Mum died the year after. It was so strange, seeing her again, beautiful, and yet so heart-breaking, because when I remember mum, it is as she was.

“Mum said she cried for weeks after she sent us away. People convinced her it was the only way to save us.”

“She was everything to us. In Russia, of course, I didn’t see her very much, because she was working, or getting food for us. There was no time. Yet before the war, she would sit on the bed and talk to me, and give me a kiss goodnight. That was wonderful. I remember the fireplace we had—piec, we called it. We sisters would sit around the piec with her, and she would tell us stories like little red riding hood, and even sometimes about the first war. That’s how I found out that she was in a war before.”

Henia could never bring herself to ask her mother in a letter to re-live the time she put five of her children on a train in the USSR, or why her brothers returned to Poland so suddenly, but seeing her again physically brought up the raw subjects—ones that the Polish Aulich household had often discussed.

“Mum said she cried for weeks after she sent us away. People convinced her it was the only way to save us. Elizabeth said Mum was screaming.”

“Mum also told me what happened when she found us in New Zealand after the war, and I heard the stories from my brothers. I still can’t get over it:

“Whoever was in the office at Pahiatua at that time had no right reading my mother’s letter to us in the first place; no right to write to her to say, ‘Take your children away or you won’t see them again.’

Henia also met her sister Marysia, who had been visiting their aunt in Ostrołęka in June 1941. There, she married a Prussian “quite high up in the railway.” She told Henia how terrified she was when they were sent to Hamburg before the end of the war in Europe.

“He wasn’t often at home because of his job. She told me how, during relentless bombings day and night, she and her children—a daughter and two sons—walked in fear, up and down the railway tracks, one suitcase between them.17

“How they all survived is a miracle—and us too. It was only by the grace of God that we are here, because we were torpedoed a couple of times on the ship coming to New Zealand. The ship went zig-zagging to make it safer.

“Even then, we children were quite resilient. We put on a beautiful concert for the captain, singing songs for him and other soldiers and officials.”

_______________

Henia remained living with the McLellans in Lyttelton and completed her high school education with typing and bookkeeping courses at her third high school, Our Lady of Mercy Convent in Lyttelton. She and Joan McLellan remained friends into adulthood.

Henia on her way to the Post Office in Christchurch Square, shortly before she married.

“I got office work and later on learnt how to operate the Burroughs bookkeeping machine. When it went wonky on me, we had to call a technician. This young man came to fix it, and three days afterwards, I saw him at a Latimer Hall dance.

“He came over and asked me to dance. We were talking, and he asked me where I was living—1 Orbell Street. I was back in Christchurch then, because the McLellans had gone to South Africa for a while. And he said, ‘That’s a coincidence, I’m boarding with Mrs Clarke at 99 Orbell Street.’

“So he barred me on his bike to my place [rode while Henia sat on the handlebars] and that’s how the romance started.

“The trouble was, he was the poorest man I could have picked up. I thought he was a dark, handsome prince, but he was poorer than I was, because at that time I was still looked after, more or less, by the authorities.

“If I had had the money, I would have got my brothers and my mum here. Of course, I was in a far better country than Poland was at that time, but they thought I had money, because this is supposed to be a country of milk and honey. It wasn’t like that for everybody.

“George’s mother was Scottish and Mr Blackler was Kiwi. They had four daughters and George, the only boy, right in the middle. The four girls slept in the one bedroom, and the mother and father slept in a sort of kitchenette-dining-front room. George didn’t have a room. Before he found that board when he started work, he was sleeping in a bath in the bathroom.

“We worked and worked, George and I, doing all sorts of jobs to pay for the engagement party, to pay for our wedding, to pay for our honeymoon. When we come back from honeymoon we had nothing.”

Henia, after her wedding ceremony on 7 April 1956, leaving the Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament (known locally as the basilica) in Barbadoes Street, Christchurch.

Henia with her “second mother,” Mrs Ettie McLellan, before the ceremony.

Henia and George Blackler after their wedding in 1956. RA Ayton Photography, then in High Street, Christchurch, took this image and the two above.

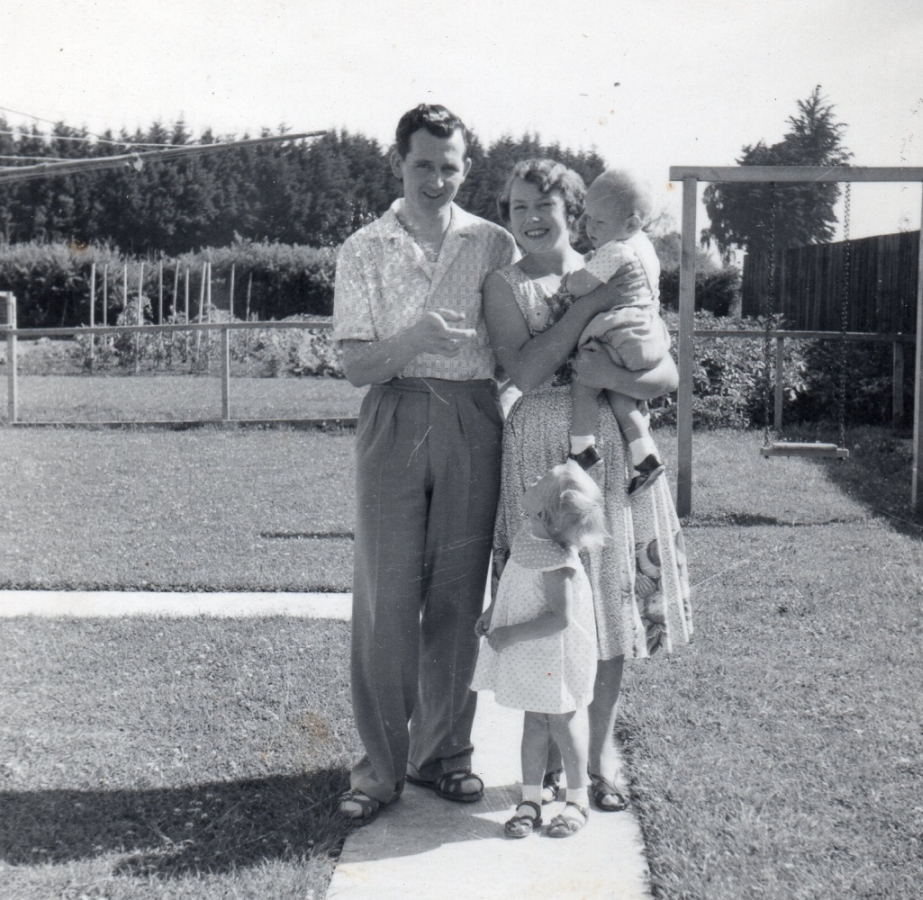

Henia and George Blackler married in 1956. When Antoni married a few years later, Henia sent her wedding dress to Poland for his bride, Halina, to wear.

Antoni Aulich with his bride, Halina, wearing Henia’s wedding dress.

“Afterwards they cut it up and made blouses for my sister Elizabeth, Alina, and my other brother’s wives. I was happy that they could make so much use out of it.”

The newly-wed Blacklers bought a house in Christchurch through a government scheme, but had to repay the loan when Burroughs gave George a promotion in Timaru. Henia was then pregnant with their third child, Paul.

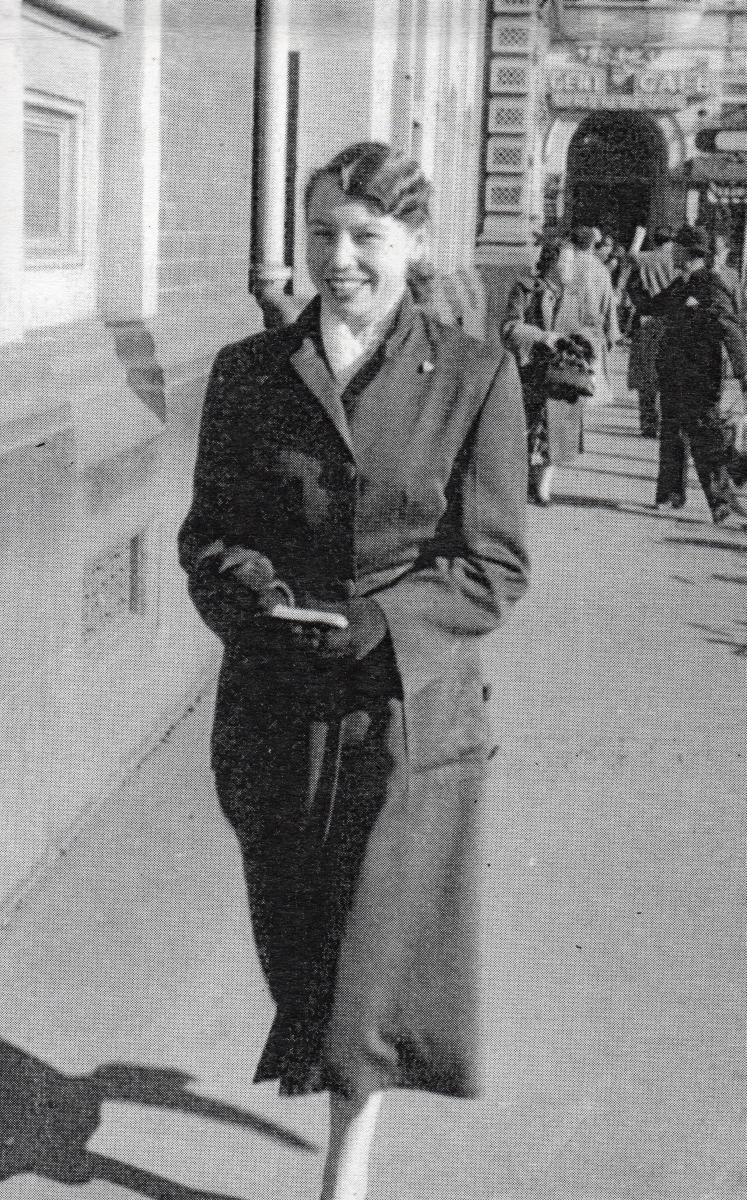

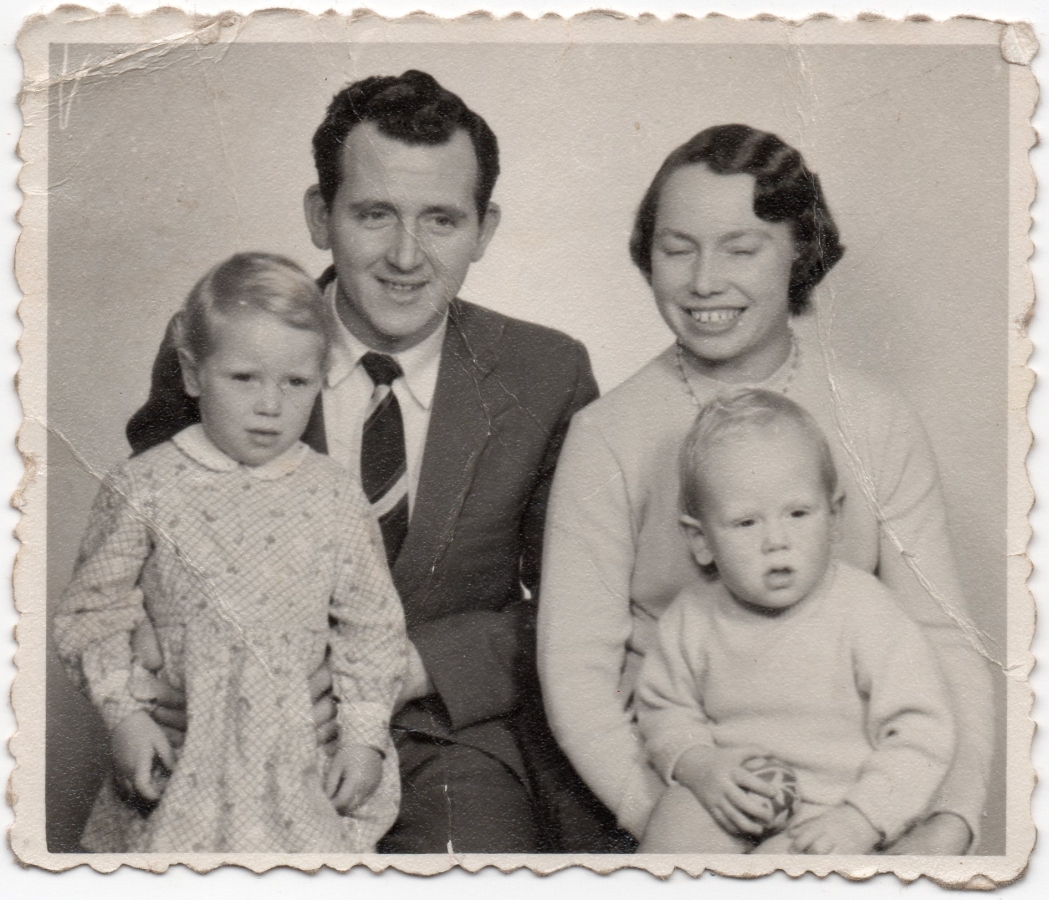

George and Henia with Christine and Gary at their first house in Redcliffs, Christchurch.

A studio photograph of the young Blackler family with Christine and Gary.

A second mortgage became the only way the young family could buy a house in Timaru, where after work, George took on painting and wallpapering, which he had learnt from his father.

“George was much better than him. He was a very exact person, a perfectionist. There weren’t many weekends when he was at home with us, and then he joined the Round Table, so we saw even less of him.”

Computers put an end to adding machines and George’s time at Burroughs. After his redundancy in 1977, the family returned to Christchurch.

Henia at home in Timaru.

With the children older, Henia had more time to spend with her Polish friends, celebrating their songs and dances at regular “dos,” including an international day that embraced 14 different cultures. Then there was no official Polish association in Christchurch.

“There was always someone in charge, though, and we met from time to time, just to be together and talk in Polish. We became more formal when the Polish people arrived in the 1980s, started to join meetings, and got themselves organised with gazettes and news and technology. Just as well for us all, because slowly they had to take it over—we were all fading like the old soldiers.”

Henia also joined an English-speaking group that entertained at rest homes.

“Our show was singing and skits, and they always wanted me to sing a song—most of the time, lili marlene. We were in a Kaiapoi club, and I sang the song in Polish, then English. Unbeknown to me, Mr Maciaszek was in the audience—he was a solicitor who was a great help to the Poles—and he stood up and clapped, ‘Bravo! Bravo!’ He couldn’t believe that somebody sang that song in Polish.”18

The later Polish immigrants to Christchurch brought with them something that had been missing in Henia’s life: traditional Polish recipes, especially those for wigilia (Christmas Eve dinner).

“When I married, I didn’t know how to cook at all, much less any Polish dishes. I stayed with four different people in Christchurch and Lyttelton, but not one of them taught me how to cook. When I boarded with Mr and Mrs Joyce in Orbell Street, wonderful, oldish people, even she never suggested that I perhaps should learn how to cook. The meal was always there for me.

“I loved going to Polish functions, as they always had some Polish baking, but I never learnt the recipes. I had no money to experiment, and was always busy with the household, my job, the garden, the church, the singing, and nursing George during the last 15 years of his life.”

The edmonds cookery book guided Henia through the early years of her marriage. While she was still living in Lyttelton, she took cookery and sewing lessons at the technical college in Moorhouse Avenue.

“I went after work. The poor woman teaching those classes; they were so big. Whoever spoke to her learnt more, but I was that shy, I kept quiet.

“I was grateful for the girls at work, Wendy, Pat and Colleen. There was Neil, second in charge, and the old man, the accountant Mr Glenn, in charge of us all. Neil took me to my first-ever ball, and Wendy took me home a few times to visit, and meet her mum and dad. She said, ‘I’ll make a batch of scones for our afternoon tea,’ and showed me how to do it. I was about 22 or 23.

“When we married was the first time I cooked a meal—sausages and gravy, and my gravy was practically white! Slowly but surely I invited people for dinner, like Mr and Mrs McLellan.

“Girls in Pahiatua called me ‘Zając’ [hare] because I had my protruding mouth. When I started working, Mr Glenn said, ‘You’ve now got some money coming to you, you should go to the dentist, and ask him to get you a brace.’

“But there was no way I could have afforded that. From my second payday, I put down a layby for a Singer sewing machine, and I made frocks for myself for going to the Latimer Hall dances. I used to go to Millers, a huge double-storey place, all materials. At lunchtimes, I would go there and try to find the prettiest patterns so that I could make a frock to go to the dance.

Henia and George at one of the social functions in Christchurch. Henia cannot recall the year, or the specific occasion, because this was her “favourite frock,” one also worn by her daughter, Christine, and granddaughter Brittany.

Throughout her life, Henia drew comfort through singing and performing, especially after George died in 2001. After her mother died, a woman from the congregation arrived at her home with flowers and scones, said, ‘You can sing,’ and introduced her to a then-fledgling choir.

“Our friendship grew, and I started to meet more people, joined other groups, and took part in quite a few Christmas pantomimes for our church and other people. I would give my arms and legs now to have somebody beside me to talk to, and decide things for me, especially with the earthquakes.

“George was good. Times were difficult but never bad. When we lived in Timaru, we had some lovely days at the Maungati river with the children, swimming and picnicking. We still reminisce about those lovely times, and the concerts and the singing and all the beautiful friends.”

One of Henia’s sorrows: her throat slowly “closing up” on her.

“I probably sang too much in my life and talked too much!”

© Barbara Scrivens, 2019

THANKS TO THE NORTH AUCKLAND RESEARCH CENTRE IN THE TAKAPUNA LIBRARY FOR THE LOAN OF AUDIO RECORDING EQUIPMENT.

ALL PHOTOGRAPHS, UNLESS OTHERWISE STATED, FROM THE AULICH-BLACKLER FAMILY COLLECTION.

ENDNOTES:

- 1 - Map from the website Archiwum Map wojskowego Instytutu Geograficznego 1919-1939,

http://maps.mapywig.org/m/WIG_maps/series/100K_300dpi/P36_S34_LOMZA_1931_300dpi_bcuj298318-287607.jpg - 2 - Ibid.

- 3 - The Battle of Łomża lasted from noon on 7 September until 10 September 1939.

- 4 - Hitler turned his troops on his former ally Stalin on 22 June 1941, with the start of Operation Barbarossa. To get to Russia proper, the Germans had to first re-occupy Soviet-occupied eastern Poland.

- 5 - In 1946, an unknown photographer recorded this map, of the German-Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation

and Demarcation document, for von Ribbentrop’s and Göring’s defence team at their Nuremburg trials.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/German%E2%80%93Soviet_Frontier_Treaty#/media/File:Mapa_2_paktu_Ribbentrop-Mo%C5%82otow.gif - 6 - Narodny Komissariat Vnutrennikh Del (People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs).

- 7 - Soviet General Serov, in a “Strictly Secret” Order No. 001223, dated 11 October, 1939, he made it clear that the “deportation of anti-Soviet elements from the Baltic Republics is a task of great political importance.” Such “anti-Soviet elements,” according to subsequent NKVD Order No. 0054, included much of the Polish population. (For more see missing humanity.)

- 8 - The list I refer to is titled List of Deportee Transports via Rail 1940-1941 by Arrival Station, Karta, 12, 1994.

- 9 - Lieut-Colonel A Ross, in charge of the British Base Evacuation Staff, report dated 3 June 1942.

- 10 - There seems to be no specific author of this list, and appears to be a continuation of the first.

- 11 - Dodatek do Nr 14 “Polski Walczacej.”

- 12 - For more, see Mason, W. Wynne, Prisoners of War, Historical Publications Branch, 1954, Wellington,

Part of: The Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939–1945,

http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-WH2Pris-_N89443.html - 13 - The general outbreak of infantile paralysis in New Zealand in 1948 closed schools all over New Zealand.

- 14 - Image from the New Zealand Electronic Text Collection,

http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-PolFirs.html - 15 - Polish Children’s Reunion Committee, 2004, Wellington, ISBN: 0-476-00739-9.

- 16 - Ibid, page 75.

- 17 - Between 24 July and 3 August 1943, during Operation Gomorrah, British and American bombers razed much

of Hamburg and killed 34,000–43,000 people.

https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-43546839 - 18 - PressReader - The Press: 2012-05-19 - Warshapedhumanelawyer,

https://www.pressreader.com/new-zealand/the-press/20120519/282359741748173