Anna Zatorska Piotrkowska

LESSONS FROM THE ‘OUTSIDE’

by Barbara Scrivens

Ten-year-old Anna Zatorska lay in her unfamiliar bed, in the tiny room a world away from her family farm in Poland, and listened to the muted chatter filtering through the thin walls.

Her housemistress1 mother, Waleria, used the room’s other bed. During Waleria’s busy evenings she left Anna alone to wonder what the girls in the four adjacent dormitories talked about.

It had been nearly five years since Anna had slept in the comfort of her own bed, with its down-filled pillow and bed coverings, her parents and three brothers nearby.

The Soviet leader’s apparent generosity stemmed from his decision to use the Poles… to help his Red Army fight Germany’s sudden drive towards Moscow.

In February 1940, Soviet Russian soldiers occupying eastern Poland ripped Anna and her family from their slumber. Under cover of darkness, the soldiers forced them—and about 200,000 other mostly rural Polish civilians—into animal transport trains destined for one of the thousands of NKVD2 forced-labour facilities in northern Russia and Siberia.

Wooden slats crudely attached to the sides of the prison wagons became the only places to rest as they made their way through the USSR. Once close to the taiga forests, the trains regularly disgorged groups. Stalin’s Polish prisoners fed his latest Five-Year plan: most cut timber for extending the railway lines.

The Zatorski family shared a log house near one of those forests with other captured Poles and hard-shelled blood-sucking insects, pluskwy, which lived in the roughly hewn walls and beds. For 20 months, sleeping went hand-in-hand with scratching painful and itching bites.

Just before their second winter in Siberia, Anna’s father, Albin, accepted Stalin’s ‘amnesty.’3 The Soviet leader’s apparent generosity stemmed from his decision to use the Poles he had incarcerated to help his Red Army fight Germany’s sudden drive towards Moscow.

The Zatorski family left the pluskwy to the NKVD’s next set of captives and joined the ragged but hopeful queues making their way thousands of kilometres towards the Polish army’s enlistment stations in the region of Tashkent, Uzbekistan.

The stranded Poles were expected to work, but received no wages, food, or even water.

Instead of allowing them through to Tashkent, however, Soviet authorities abandoned their group in a Kazakhstani kolkhoz. The stranded Poles were expected to work, but received no wages, food, or even water. The Zatorski family found an empty hut to sleep in, but their situation became so dire that Albin talked of returning to the NKVD facility.

During the next few months Anna lost one family member after the other.

She last saw her emaciated father and oldest brother, Józef, when they left that kolkhoz on a second attempt to find the Polish army. Władysław was later accepted into the Polish army’s cadet school but Anna cannot remember how she, her mother, and younger brother, Marian, managed to escape the USSR.

In Persia (now Iran) Waleria worked in a Teheran hospital until Marian died after falling out of an upper storey dormitory window. (See memories that remain.)

_______________

Anna appreciated exchanging the dust of the Middle East for the familiarity of a farming community. The New Zealand hills were steeper than those around her hometown, Waniów, and the camp population far larger, but she felt safe again. She had her own bed, a pillow, sheets and blankets.

She loved being with her mother—and knew how lucky she was to have her alive—but could never able break through the invisible wall of camaraderie that enveloped the other girls.

“I was not treated differently by the adults. The children made that distance.”

Anna and Waleria’s sleeping arrangement had been completely logical in Persia. After Marian’s death, they moved to Isfahan, where Waleria worked as a so-called “housemistress” at a Polish boys’ hostel. From 1942 to 1944, Polish children and their caregivers lived temporarily in mansions, monasteries, convents and other institutions scattered around Isfahan. They numbered up to 2,590 in 1943.4

On 1 November 1944, Anna stepped on New Zealand soil with 732 other Polish children and 105 Polish adults invited by the New Zealand government to stay until the war ended. Unlike in Isfahan, New Zealand authorities elected to base all the Poles in one place.

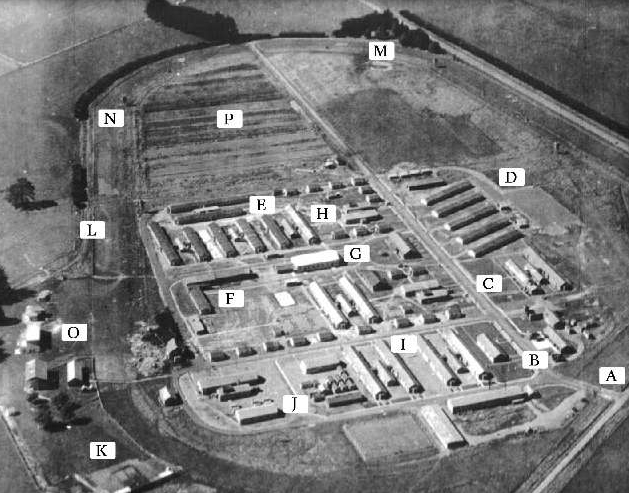

The only suitable accommodation appeared to be an enemy alien internment camp created in 1943 on the site of a racecourse south of Pahiatua. Its 180 prisoners were returned to Somes Island, Wellington, and the New Zealand army modified it for the Polish children by building classrooms, dining rooms and a huge communal hall.

Children with parents lived with them in separate staff quarters or, like Anna, within rooms in one of the eight dormitory blocks.

“We were not exactly part of the group. I was not treated differently by the adults. The children made that distance. I could never be close to them. I was in the dormitory, but I wasn’t, I was in a little room with my mother.

“The other girls would say, ‘Oh, but you’ve got your mother, that’s why you’re not doing this or that: You’ve got your mother…’

“Mind you, I know there was a bit of an advantage for one of the girls in my class. Her mother was a teacher. We had to share books. There were not enough books, but she always had a book. The rest of us would have to share, and sometimes you got a book, and sometimes you didn’t, and you still had to do whatever you had to do. I also said to her, ‘You’ve got a mother, that’s why you’ve got the book. I can’t get that book but you’ve got it.’

“There was always that dividing line, even now. When I came from Marton to Wellington in 1953, I knew so many girls, and I made lots of friends, but I was never as close to them as the kids from the ‘real’ Pahiatua camp, because I ‘had a mother.’

“I spoke to some of my friends about it—and I’ve got really good friends now—and they said, ‘Yes, that’s how it was.’”

Waleria Zatorska is standing second from the left in this photograph of Pahiatua caregivers and domestic staff. The others standing from left are: Leon Rudolf Rosenberg-Łaszkiewicz, Maria Węgrzyn, Stefania Nawalaniec, Ewa Benasiewicz, Elwira Kundycka, Paulina Jania and Julia Rolińska. In front, from left, are Zofia Sprusińska, Zofia Kołodyńska, Father Michał Wilniewczyc, Janina Kornobis, Weronia Woźniak, Helena Białostocka, Zdzisława Blaschke and Balbina Wojtowicz.5

Despite the detachment of her peers, Anna has happy memories of Pahiatua.

“The camp was well-provided, and we could go every so often—with special permission and not too big a group—to have a look at Pahiatua, the ‘big city.’

“Every Sunday we had lots of New Zealanders visiting us, bringing lollies and chocolates and cakes and biscuits. They were wonderful, wonderful people. Every Sunday there was somebody arriving—in the afternoon, because in the morning we had Mass.

“I remember once we had a Maori group doing the haka.

“The concert they gave us was lovely, with the grass skirts and everything, but when it came to haka, a lot of us wanted to leave the hall. They made their eyes wide and jumped and pulled out their tongues… We thought they were going to eat us. It was frightening, especially for the little ones sitting in the front.”

_______________

The camp layout. The girls’ dormitories were located at (E), the boys’ dormitories at (I). The classrooms were (D), and the large white building at (G) was the communal hall. (L) marks the site of the grotto.6

Ages in the separate boys’ and girls’ classrooms varied by up to three years, depending on the children’s levels of education when Soviet soldiers kidnapped their families in 1940 and 1941, and their circumstances in the various NKVD forced-labour facilities and kolkhozes.

“I liked most subjects but I struggled with maths up to Standard Three or Four. Then we got Pani Bucewicz and my marks shot up.

“The way she explained… We always had tests. She spread the desks out so we couldn’t copy from anybody else… she would walk up and down and she watched how you were working out the problems, and when the test finished, she would take the papers and ask, ‘Why didn’t you…? What didn’t you understand? Why did you do it like that?’ And she would explain.

“I thought that was so great. She was only little, but she was so good.”

Anna’s favourite teacher, Maria Bucewicz, seen here with, from left, Elżbieta Kruszyńska, Zofia Iwan and Cecylia Gawlik.7

“I liked geography and nature study. We did not learn much about New Zealand because we were going back to Poland. History was good, but the teacher was elderly and she would ask us when this war took place, or what happened on this or that date. We would write out a list of all the dates and pin it on somebody sitting in front of us—I think half the time she was sleeping—and read out, ‘This happened then… that happened then.’ Dates, dates, dates, and so you passed history.

“We really resented the English teacher. Some of the kids picked up the language and loved it, but a lot of us didn’t want to learn it. We found it quite hard and we just didn’t want it. She was a New Zealander, not knowing any Polish language at all, and she’s trying to teach us English?

“We were horrible to Miss Isaac, and I remember her picking up a chalk and throwing it at somebody because she got so upset.

“We had one Polish lady trying to teach us physical education and—I remember it like today—she took us out to the big paddock behind the school and she told us to strip off completely. Some of the girls were already developing and she made us jump, and do this and that… Some of the girls were crying.

“She only did it once. That was the end of it. Physical education no longer belonged to her.

“There was a piano that some of the kids wanted to play, and we had Mrs Kalińska to teach us embroidery. I loved the embroidery classes. We made lots of lovely things. I don’t know what became of it all. We couldn’t keep any of the stuff that we embroidered.

“She also used to teach drawing and painting. In my class we had two really good painters. If it was somebody’s birthday, we would make laurki [decorated cards]. They would paint a lovely picture and we would write some nice words.”

_______________

The camp lay in the Mangatainoka river valley near the road that later became State Highway 2. By the time the Polish children arrived, dairy and sheep farmers had cleared much of the original dense bush.

The Polish caregivers carried their own sorrows and were not necessarily trained to cope with similarly traumatised children.

In summer the looping river, so like Polish rivers meandering through villages the children left behind, provided dozens of swimming spots. Boys tied up ropes for swinging in the trees and some acquired bikes.

“Some boys were so horrible. I remember one… I was so scared of him, because if you walked anywhere and he was coming, he would shout at you, ‘Get out of the road, get out of the way you baba!’

“They were more or less the same age as me, maybe a little bit older, but some of them just yelled, ‘Ty babo! Get off my way!’ As if I were a really old woman. It was pure aggression, and it wasn’t because of my mother.”

Emotional and physical trauma shaped all the Poles in Pahiatua. Some had lost entire families. The Polish caregivers carried their own sorrows and were not necessarily trained to cope with similarly traumatised children. Today’s society recognises post-traumatic stress better, but then, only luck determined whether a conflicted child had emotional or family support.

At one of the Pahiatua reunions, one of the ‘boys’ told Anna that he received regular “hidings,” while another said, “Nobody laid a finger on me.”

Anna remembers one of the teachers taking a group for a walk through the remote farming district:

“He took us somewhere on the mountain. I can’t remember exactly where, but I know we were a long way away from Pahiatua. We sang harcerskie [scouting] songs. It was great for the older children, but some of the young ones were so tired, in the end they had to be carried on the older ones’ backs.

… camp authorities began to accelerate the children’s integration into the wider English-speaking society.

“I don’t know how many children went, but it was quite a big group and there were quite a few hills. We found some sort of lasek [grove], not quite a forest, but quite a few trees. We never went again.

“I think the teacher had something to do with the boys because some of them were quite a handful. The people who looked after those children, I think they deserved more than a medal.”

Anna, a girl guide, enjoyed that walk and other scouting activities organised at the camp that were similar to those in pre-war Polish schools.

“We used to go to the grotto and say prayers and sing. There would be somebody older, one of the college girls or Mrs Kozera, in charge, and we would sing different songs. We went quite often, especially in May and on Sundays, but sometimes we would just go there because we felt like it, and say a little prayer.”

By 1946, when it was clear there was no free Poland to return to, camp authorities began to accelerate the children’s integration into the wider English-speaking society. More teenagers left the camp for high schools all over New Zealand.

New Zealand Prime Minister Peter Fraser settled any possible post-war predicament by declaring that the orphaned children could wait until they were 21 to decide whether they wanted to return to communist-controlled Poland. Some adults and children found and joined family members in Poland. The Red Cross started to reunite Poles in New Zealand with family members abroad.

“Some men came from the [Polish] army and helped to after the boys. They were growing up quickly, and the army men made them march and do all sorts of things. They were very strict with the boys, and then they had to keep an eye on the girls too, because later on, when the men from the army came, quite a few got pregnant.”

_______________

Anna stayed behind when Waleria went to work for an Italian priest in Pungarehu, south of New Plymouth, and for a time did join the girls in the dormitory. She left the camp to finish her Standard Six at the Catholic school in Opunake, 20 kilometres south of Pungarehu. Although the only Polish girl there, Anna had absorbed enough English to slot in easily.

“I learnt that you can never be late for anything. The bell rings and you go, you just go!”

Opunake did not have a Catholic college, so the following year Waleria enrolled Anna into the Sacred Heart College in New Plymouth. Anna became its only Polish boarder, although there were Polish day students.

“They didn’t have many boarders because they were closing the convent. The building was very old. We were about 10 girls in one dormitory. The girls in the beds close to the windows closed them because they were cold, but I was somewhere in the middle, and suffocating.

“Six o’clock, you had to get up, go to Mass, and then breakfast. I learnt that you can never be late for anything. The bell rings and you go, you just go!

“After school we could have afternoon tea and a little scone or something. You had to go and get it. There was a little window: you slid it up and got your afternoon tea. One day I was a few minutes late. The nun saw me. I had my arm out and was just about to take my tea and scone and she shut the window in front of me. That was it.

“I was a very hard person to feed in Pahiatua because I didn’t like this, I didn’t like that, but at Sacred Heart I was always hungry. There was never enough food. There must have been, but the prefect, the head girl, gave out the portions. You could not help yourself, and the nuns didn’t put the food on your plate. It was that person serving you, so if she liked you, she might give you a little more, but if she didn’t… And she had really good friends.

Sometimes the whole period would go and you couldn’t get to a typewriter, and at the end, you had to leave and go to another class.

“Mum visited me once a week. The priest would bring her to New Plymouth. I never had to go to footie on Fridays: I was let out so I could go with my mother. She would buy me, say, a tin of biscuits to take back to school. We all had cupboards, but every time I went back to my cupboard, my cupboard was bare.

“We had extra English lessons but we were always ‘just the Polish group.’

“I took shorthand typing: you always had to fight to get to a typewriter. Sometimes the whole period would go and you couldn’t get to a typewriter, and at the end, you had to leave and go to another class.

“The same with the sewing: it took me a whole year to make a little apron. I had to sew it by hand because I couldn’t get to a sewing machine. That didn’t worry me, because I was quite good at embroidery, but that’s how long it took.

“One good thing was how they dealt with homework: you had tea [evening meal], then you had to go to a special study room to do your homework. There was always a nun sitting at the desk. If you needed any help, you could go over and ask her quietly.

“Quite often the next morning, I would go to my classroom and I’d have all the homework done and some girls would say, ‘Oh yeah, it’s all right for you, the nuns helped you out,’ but that was the routine and I thought that help was great.

“I was only there for a year. My mother met my stepfather [Polish war veteran Antoni Characzko] and married, and that was the end the convent for me. Mum couldn’t afford to pay, because it was expensive. In some ways I was glad.”

_______________

“In Marton everything was provided. Everybody had a typewriter. Everybody had a desk.”

Anna moved to Marton to live with her mother and Antoni, one of the carpenters employed to build the Lake Alice Psychiatric Hospital in nearby Rangitikei. Waleria sewed candlewick and chenille bedspreads in a local factory.

“They bought a little place in Marton. By that time my brother was coming from England. My stepsister, Helena, younger than me, still went to the convent as a primary student. I went to Marton college—such a big, big, big difference.

“In New Plymouth the girls would be chosen for, say, the basketball team, good runners, good throwers… and the ones who weren’t that sporty, well, we just had to sit there and watch. When I went to Marton—a public school, mixed boys and girls—you always had to do something during the a sports lesson. One girl had a heart problem. She had to throw rings on a stick. I joined girls playing hockey or rugby. I wasn’t in any team, but I had to do physical education, I just had to do it. There was no excuse unless I had a note.

“In Marton everything was provided. Everybody had a typewriter. Everybody had a desk. We were even taught cooking, very plain things like making jam or making scones, practical knowledge, things like Mothercraft: How do you look after a baby?

“There was a woman who came with a baby to show us how to bathe it, how to dress it, how to start getting the baby on the potty. We were just starting secondary school, but girls used to get married quite young in those days.

“I always remember the poor baby, just little, and she’s holding him over the little potty, and that’s how I taught my own kids. By nine months, they were out of nappies, even Alex, my grandson. I used to take him to playgroup and he never had to wear nappies.

“It was the same with the sewing. We were taught how to work out a pattern: if you wanted pleats or something else in the skirt, how to increase or decrease the amount of material. I really liked that, and I did quite a bit of sewing later on.”

By the time Anna left Marton District High School, she spoke English fluently.

“Now I find it harder. I mispronounce words. Now you can pick me out that I am from another country, whereas before, I don’t think many people did. I can even hear it myself that I don’t speak English as I used to. I was more fluent. Mind you, we always spoke Polish at home with Władek.”

_______________

“… you were so different. You talked about the chooks that you had to feed. You had to go and work in the garden…”

Around 1950 Anna’s brother Władysław needed part of a lung removed, which led to an extended stay at Wellington hospital. Zofia Piotrkowska, Władysław’s mother, lived nearby with her daughter, Maria. Zofia and Waleria knew each other from Pahiatua and met on the street one day. In typical Polish fashion, Zofia insisted that Waleria and Anna be her guests when they were in Wellington.

War veteran Władysław Piotrkowski, then 27, had recently arrived in New Zealand from England and lived nearby with his younger brother, Zbigniew.

“Władek always said that his mother told him, ‘Mrs Chareczko is coming with her daughter to see her son. You should meet her.’ He said, ‘How old is she?’ And when she told him, he said, ‘Mum, that’s a child, I want a woman and not a child.’ His mother said, ‘It doesn’t matter. You come and see her. You come for a meal and you meet her,’ but I remember meeting him before then.

“I started working in Marton as an assistant in a boutique. One day I went to Wellington with my mother. Being a small-town girl, going to the city was a big event. There was a big Polish dance at one of the Newtown halls and I first met him there.

“He had other friends. When he arrived in Wellington, there were lots of girls, and lots of Polish girls. He could choose almost any one, but he said, ‘I will not marry a New Zealander, and not an English woman, because I’ve seen my friends marry in England, and it wasn’t a marriage.’

“He met some Polish girls he liked, but they said, ‘You haven’t got anything. I want somebody who has got this and that, nice car and nice that…’ and Władek said, ‘Well, I haven’t got any of that,’ and let them go.

“Years later he told me, ‘When I met you, you were so different. You talked about the chooks [chickens] that you had to feed. You had to go and work in the garden.’

“That’s how it was in Marton. I had to do the shopping because mum and dad worked. Mum would say to me, ‘Get this and this and this ready for dinner and when I come home, I’ll finish it.’

“But I did like him the first time I saw him. I thought he was very handsome, beautifully dressed. He had very nice manners. That’s what I liked about him, and yet I never thought I’d marry him, because there were so many girls in Wellington.

“And then one day a friend invited him to Palmerston North to be a godfather. The mother had two sisters. After the christening, the father went to the races, but Władek decided to come to Marton to visit me. He had to go by bus or by train, because nobody had cars then.

“At that time with the Poles, anybody from anywhere could knock at your door and say, ‘Hello, I haven’t seen you for ages,’ or, ‘Hello, this is my friend, so-and-so.’ It was a very popular thing to do. You never had to ring up somebody to tell them you’re coming. Whatever food you had at that time, you put it out on the table and everybody had a good time.

“And then later on, when Władek’s brother married [Pamela Miscall], I was invited to be a bridesmaid, with Władek a groomsman. I didn’t know the bride at all before the wedding and I hardly knew Zbyszek. He had a big motorbike. He and Władek were so different.”

Anna and Władysław married on 3 January 1953, at St Francis Xavier church in Marton. Waleria’s former employer and Italian friend, Rev Eugene Carmine of Pungarehu, officiated.

“My mother really wanted that priest to marry us. He was such a good friend of the family, such a warm man. When I was at boarding school and home for the weekends, he used to take me with him to the Maori settlement where he helped out. He said that one day I would make a great nun.”

Władysław and Anna after their marriage ceremony. With them is the Rev Eugene Carmine and Anna’s brother Władysław, who was one of the groomsmen. Anna's stepsister, Helena Choraczko, one of the bridesmaids, is behind her. The flower girl is Danuta Wos.

At Władysław and Anna's reception, right, with Waleria and her second husband, Antoni Characzko and above, Zofia Piotrkowska on the same day.

Władysław Zatorski married Alicia Dombrowska, whom he met on holiday in Poland.

“They married again when they came back because in Poland it was only the civil wedding, and my mama said that they should have a proper wedding.”

_______________

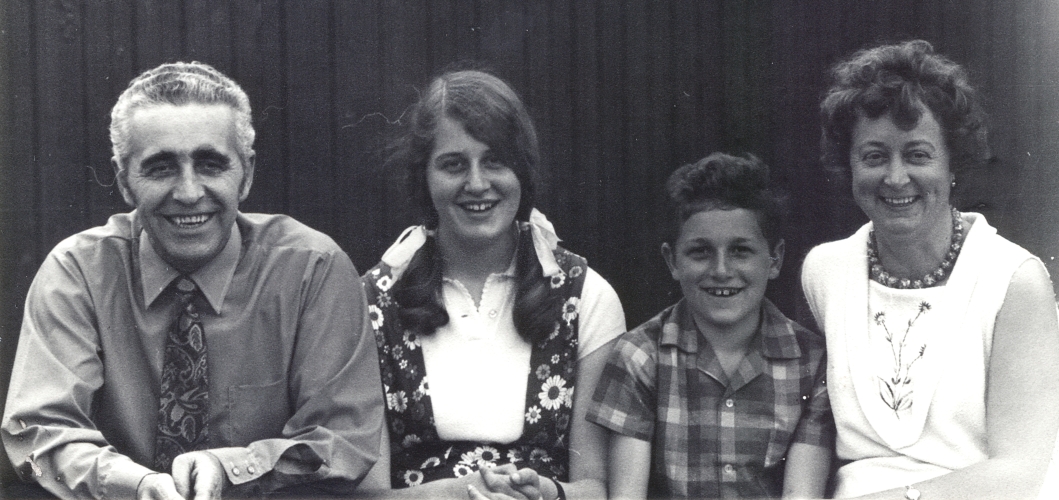

Władysław, Basia, Bogdan and Anna Piotrowski.8

The Piotrkowski’s first child, Basia, was born in 1958 when Anna and Władysław were still living in Daniell Street, Newtown. Bogdan arrived five years later, when they lived for a few months in Titahi Bay, Porirua.

“We always spoke Polish with the children. When Bogdan started kindergarten—he must have been about three and a half—the teacher said, ‘You shouldn’t be bringing him here because he cannot speak English.’ I had to help out, she said, because of that, but Bogdan made his own connections with the other kids. They play; they don’t have to know the language. He didn’t need me there.

“Later on a different teacher came to the kindergarten. She said, ‘He’s good, there is nothing to worry about.’ I didn’t have to stay with him.

“When he went to primary school, I asked the teacher how he was getting on. She said, ‘He’s the top of the class.’

“He had a friend living not very far from us, David, a lovely boy. My Bogdan would try to speak English, try to give a different twang. They were good as gold. They used to know how to talk to each other. That little David, when the other kids were walking home from school, he’d be waiting in the street and he would give them hidings, and yet he and Bogdan never had one fight, ever.

“He was a little bit older than Bogdan, and one day came to our place after school and started to complain. I said, ‘What happened, David?’ He said, ‘Ooh, I was belting them and they all came climbing on me.’ He never touched anybody after that. His mother and father were always fighting, and every time he’d come to our house, he would tell me a different story about what his father was doing. He wanted to have a father doing something wonderful.”

The Piotrkowski family at Anna's 60th birthday celebrations in 1994.

_______________

Anna is now a great-grandmother, something that has helped her cope after her husband’s death on 1 February 2015. Basia, a teacher, married Murray Powell, a school principal. Their son, Aleksander, now has two sons of his own, Ryder and Jakob. Bodgan died on 15 March 2013. His widow, Jane, née Mabson, and two sons, Jordan and Vincent, live close enough to their babcia for regular visits.

Anna with Basia in the Piotrkowski kitchen.

A certain café in Lower Hutt hosts a full table of Polish chatter most Sundays after Polish Mass in nearby Avalon. Congregation members like Anna gather casually and enjoy one another’s company for an hour or so. It is not the 800-strong Little Poland of Pahiatua, but it remains an appreciated link to old friends and their Polish heritage.

Anna’s invisible walls have long lost their power.

© Barbara Scrivens, 2017

Updated May 2019.

THE LAST PHOTOGRAPH BY BARBARA SCRIVENS. UNLESS OTHERWISE CITED, ALL OTHER PHOTOGRAPHS FROM THE PIOTRKOWSKI COLLECTION.

THANKS TO THE NORTH AUCKLAND RESEARCH CENTRE IN THE TAKAPUNA LIBRARY FOR THE LOAN OF AUDIO RECORDING EQUIPMENT.

ENDNOTES:

- 1 - I made the decision to stay with the old-fashioned term because that is the employment

description used for Waleria Zatorska and many others in the book Isfahan, City of Polish Children edited by Irena

Beaupré-Stankiewicz, Danuta Waszczuk-Kamieniecka and Jadwiga Lewicka-Howells, OBE, Association of Former Pupils of Schools,

Isfahan and Lebanon, 1989, ISBN 0 9512550 1 2.

Pani Anna described her mother as one of the wychowawczynie, for which the translation “carergiver” does not do justice. - 2 - The NKVD, or Narodny Kommisariat Vnutrennikh Del was the Soviet Union’s Secret Police, known officially as the People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs.

- 3 - In this and other stories, I use the apostrophes to show that the ‘amnesty’ was a farce. An amnesty is defined as an official pardon for those who have committed political offences, but the Poles living in eastern Poland in 1940 and 1941 did nothing to deserve their abduction to the USSR. If Hitler’s Operation Barbarossa had not threatened his former alliance partner, Stalin would not have turned to the West for help.

- 4 - Ibid, Isfahan, City of Polish Children, page 127.

- 5 - New Zealand Electronic Text Collection, through Victoria University of Wellington

Library, NEW ZEALAND'S FIRST REFUGEES: PAHIATUA'S POLISH CHILDREN ,

http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-PolFirs-t1-g1-g2-t52.html#n192, page IX. - 6 - Ibid, page IV.

- 7 - Ibid, page XVII.

- 8 - The Piotrkowskis could not remember who took this photograph. If anyone can identify her, please let us know.