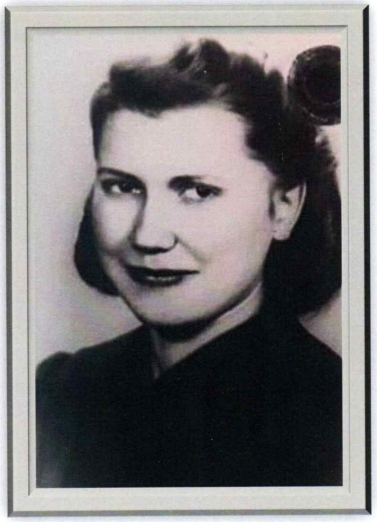

Jadwiga Zarnowska Zychewicz

Jadwiga Zychewicz, née Zarnowska, died in Masterton on May 12, 2019. This excerpt of her life was taken from the eulogy delivered at her funeral by Karl du Fresne, the husband of her daughter Jolanta.

Jadwiga Zarnowska was born in Warsaw on September 22, 1922. She was one of two children born to Józef Zarnowski, who worked on the Warsaw trams, and his wife Zofia. There was one sibling, a younger brother named Jerzy, who died aged seven from diphtheria. Another younger brother was stillborn.

Jadwiga grew up in Warsaw and had particularly fond memories of holidays on a small farm belonging to an uncle and aunt. The uncle died of gangrene from a wound suffered in the First World War—war is a recurring theme in this story—and the farm was subsequently run by the aunt and her daughters, one of whom Jadwiga remained close to throughout her life. That cousin, whose name was Lodzia, was the only member of Jadwiga’s extended family that we know of who survived the terrible upheavals of the 1939–45 war.

In notes that we encouraged Jadwiga to write several years ago, she recalled some of those holidays on the farm. I’m going to quote from those notes because they convey an impression of a happy time before war changed everything.

Bear in mind this is written in Jadwiga’s distinctive English. She had a very good understanding of English and spoke it quite well, but she had little experience of actually writing, so the tenses are sometimes wrong, she refers to herself using third-person pronouns, and definite articles are missing.

“It was good time sitting in the shadow of wild pear tree. The girls were happy together. They had talked, laughing. They could see the lark singing in the sky.

“Also under the tree were plenty of small fruits. During cows milking, Lodzia and Jadzia (‘Jadzia’ was Jadwiga’s childhood nickname) had waited patiently with pot for fresh milk. Always Lodzia’s mother Jozefa did the job.

“Later, the milk disappeared in the cellar. The milk was used to make butter, cheese or sour milk for morning breakfast with potatoes.”

She also wrote about foraging for wild mushrooms and berries. These were cherished memories which are made all the more poignant by the terrible events that were to come later.

Turning to Jadwiga’s father, we know from her notes that he was conscripted into the Russian military at a time when Poland was under Russian rule. He was away for seven years and obviously contracted some sort of chronic illness, because he was exempted from fighting when Poland and the Soviet Union subsequently went to war in 1919—a war that Poland won.

For the first few years of her life Jadwiga lived with her parents in a one-roomed apartment in Warsaw. When her younger brother arrived they moved to slightly more spacious accommodation, although there was still just one room and only cold water. They shared a downstairs toilet with other residents of the apartment block.

Jadwiga recalled a fresh fruit and vegetable market in the square outside—a “spectacular” square, she wrote, with new paving. She remembered playing with the neighbourhood children in the square, with the older children organising games and singing.

These were the best years of her childhood, she wrote. She also remembered her father painting the apartment in bold colours and going fishing on Saturdays. These simple things obviously stuck in her memory, perhaps because they stood in such contrast to the appalling events that were to happen later.

But she also wrote of the terrible shock when her younger brother suddenly died in 1934. She recalled going for walks with her mother on the banks of the Vistula River and thought these walks helped her mother recover from the loss.

Jadwiga commenced school at seven, first attending a private school run by nuns and later going to college for four years. She was 17 when the Germans invaded in 1939 and closed all the colleges and universities, thus denying her the opportunity to take up a scholarship she had won.

By now the family was living on Daleka Street, close to the centre of Warsaw. Jadwiga described a happy life there in the pre-war years, with lots of social interaction with aunties, uncles and cousins. It was a bigger, more comfortable apartment with its own toilet and a big cellar where they stored coal and barrels of sauerkraut.

Everything changed on September 1, 1939, when Jadwiga got some books from the library and took them to read on the grass by the airport not far from her home. She wrote: “It was something different this day.” She noticed that the airport was deserted and when she looked up, she saw what she thought was a solitary bird, very high in the sky. It turned out to be a German plane—the first of many. World War Two had begun with the Nazi invasion of Poland.

Under German occupation, Jadwiga at first tried to get on with life as normal. Colleges had been closed but she defied the Germans by continuing her studies in private homes, walking with her books concealed under her jacket.

The war brought hardship that we can barely begin to imagine. Parts of the city had been flattened by bombing and food was scarce. For three years the Zarnowski family survived mainly on soup, but the poor nutrition and freezing winters inevitably affected their health.

Jadwiga’s mother died in 1942, aged 49, and her father only a few months later, at 50. Jadwiga told of being alone with her much-loved father on the night he died in awful circumstances, coughing up blood, and of sitting with his body all night in pitch darkness because a night-time curfew and blackout prevented her from going out to seek help.

Tuberculosis was rife and Jadwiga became infected in one lung. She was admitted to a sanatorium ran by nuns outside Warsaw which, remarkably, continued to function. Just as remarkably, she remembered that as a period of relative happiness.

She also remembered going with another patient to church in Warsaw on Easter Sunday. Their route took them past the wall of the Jewish Ghetto and they could hear shooting on the other side. This would have been in the last days of the Ghetto, shortly before the Nazis destroyed it after first deporting 250,000 Jews to the Treblinka extermination camp.

While in the sanatorium, Jadwiga befriended a fellow patient named Krystyna Zychewicz. She too had lost both her parents. Krystyna had two sisters and two brothers, one of whom was named Antoni. Jadwiga would end up marrying him.

It was Antoni who came to Jadwiga’s rescue when she found herself stranded on a farm 150 kilometres from Warsaw, where she had been employed looking after a child whose mother was sick—a wretched time in Jadwiga’s life when she was lonely and badly treated. Her travel documents were out of order, preventing her from returning to Warsaw, and she was afraid to apply for new papers for fear of punishment by the Germans. Antoni obtained a forged identity card for her.

Antoni at that time was a member of the Polish underground, also known as the Home Army. His job was to monitor British radio broadcasts on a clandestine radio and to print news sheets for distribution to other members of the resistance movement. Both the radio and the small printing press he used were strictly forbidden and he would have been jailed or executed had they been discovered.

Jadwiga recalled a narrow escape when she and Antoni were sitting in the apartment on Daleka St with some of his clandestine newsletters on the table in front of them. The door burst open and a German soldier strode in, demanding to see Antoni’s identity documents. Fortunately his attention was focused on Antoni and Jadwiga was able to shuffle the illegal documents out of sight.

Jadwiga married Antoni in Warsaw on Boxing Day 1943. Despite the privations of the time she recalled a joyous wedding with a large choir and, astonishingly, good food.

Two months later, Antoni’s brother Kazimierz was arrested and taken to Sachsenhausen concentration camp near Berlin, where he died. The Germans had discovered telltale parts of a radio that Kazimierz had secretly been using. Someone had apparently informed on him.

Jadwiga kept a letter that Kazimierz had sent Antoni from Sachsenhausen—a letter written in German because he wasn’t allowed to correspond in Polish. We still have it, along with his ID card. He was one of 22,000 people murdered in Sachsenhausen.

In August 1944, the Home Army launched an all-out offensive against the German occupiers in what became known as the Warsaw Uprising. The Germans responded with savage reprisals, systematically destroying the city and ordering the evacuation of the civilian population.

Jolanta Zychewicz du Fresne, at a memorial to the Home Army on the corner of Daleka and Tarczyńska Streets in Warsaw. A translation of the plaque says that it was the site of one of the three mass murders carried out between August 3 and 5, 1944 on defenseless civilians by an SS company occupying the former school building at 8 Tarczyńska Street. The crimes were acts of terror and revenge for the insurgent activities carried out in the area. The inhabitants were murdered in the cellars with shots to the back of the head; their bodies burnt. More than 200 other people were murdered at nearby Grójecka Street.

When the order came to leave their apartment, Jadwiga and Antoni were given no time to pack their belongings. Her most treasured possession, her cherished photo album, wouldn’t fit into her bag, so she settled for an envelope containing her wedding photos.

In the street outside, their neighbour’s 15-year-old daughter was shot in the neck for taking too long to obey orders and bled to death in front of them. Drunk Ukrainian soldiers, who were carrying out the evacuations on behalf of the Germans, were demanding the evacuees’ watches and jewellery.

In the stifling heat of summer, Jadwiga and Antoni joined thousands of other evacuees—including the old, the young and the sick—on a long march to a large hangar-type building on the outskirts of Warsaw where they remained for two nights without food. They saw a procession of people being ushered through a large side door and suspected—correctly, as it turned out—that they were bound for Auschwitz.

Then a German officer called out, asking if anyone wanted to go to Germany to work. A Mr Wroblenski, who had been a neighbour and a workmate of Jadwiga’s father, stepped forward and put his name down. Trusting Mr Wroblenski’s judgment, Jadwiga asked him if she could travel on his family papers under the pretence that she was his daughter and Antoni his son-in-law. Mr Wroblenski obliged and by doing so, probably saved their lives. They exited through a different door and were put on a train for Germany. It was a slow three-day journey in a cattle truck without food or water, but it was preferable to a death camp.

They were placed in a labour camp and Antoni was put to work seven days a week in a Mauser factory, producing weapons for the Wehrmacht. Because of her TB, Jadwiga was allowed to work in the camp as a cleaner rather than undertake more arduous factory work. She recalled the camp commander as a humane man—evidence that not all the Germans were monsters.

When the camp was liberated by French soldiers in 1945, Jadwiga and Antoni were moved to another camp, then to a hospital and later again to a camp especially for Poles.

At this stage they had to make a crucial decision: whether or not to return to Poland. By now Poland was under Soviet control and they were hearing stories about friends who had returned to their homeland and disappeared or been arrested. They decided not to go.

Instead, Jadwiga and Antoni ended up living in a converted bomb shelter near Stuttgart. It was during this period that their first child, Wanda, was born in 1948, followed by Jolanta in 1951.

Things looked up when they were able to move into a new apartment built by the Americans under the Marshall aid plan. The four other Zychewicz children—Maryla, Andrzej (Andrew), Stanisław (Stan) and Halina—were all born in that apartment at 151 Zuckerbergstrasse. Antoni worked for the American army as a communications technician at Bremerhaven, far away in the north of Germany, and would return home every few weeks on weekend leave.

It can’t have been an easy life for Jadwiga, raising six children solo in a one-bedroomed, fourth-storey flat with no lift. I asked Jolanta what she remembered about her mother during this period and the first thing she said was that Jadwiga always had a pot of soup on the stove. Soup and fresh bread and cheese from Mr Bossac’s shop on the ground floor were the staples of the family diet. Mr Bossac would allow them to put everything on credit and Antoni would pay the bill the next time he came home.

But it was never their intention to remain in Germany, and for years they sought to emigrate: first to the United States, then to Canada. Neither country would take them because X-rays showed that both Jadwiga and Antoni had lesions on their lungs from TB, and neither the Americans nor the Canadians wanted people who might suffer prolonged ill health.

Eventually Australia agreed to take them and the necessary arrangements were made. Then another quirk of fate intervened. The family had had Polish neighbours in Stuttgart, the Arlukiewicz family, who had emigrated to Wellington. The Arlukiewiczes wrote them a letter saying “forget Australia—come to New Zealand.” And so it was that the Zychewicz family arrived in Auckland on the ship flavia in August, 1965.

At first they settled in Palmerston North, where the local Methodist community had found a house for the family and a job for Antoni. They arrived in Palmerston North on the overnight train to be greeted by an official reception party and a newspaper reporter and photographer who put them on the front page of the manawatu evening standard. The headline described them as refugees—technically not correct, although they were officially stateless and would remain so until they became New Zealand citizens in 1969.

The family was ever grateful to their Palmerston North hosts, but provincial Palmy was something of a culture shock. They were bombarded with free food and on one occasion were given a leg of mutton, a type of meat Jadwiga had never encountered before. Not knowing what else to do, she boiled it. The kids fled the house holding their noses. Jolanta reckons it put Wanda off sheepmeat for life.

Things didn’t quite work out in Palmy. Antoni’s job wasn’t suited to his skills and within months they relocated to Wellington, where he got a job as a technician in the Civil Aviation Department and the family moved into a migrant hostel in Lyall Bay – a grand old mansion that later became the residence of the papal ambassador and is now owned by Sir Peter Jackson. For the first time in her life Jadwiga got a paid job, working in the Wellington Hospital laundry.

Later again they moved into a state house in Champion Street, Porirua East. Andrew and Stan became foundation pupils of Porirua’s Viard College and Jadwiga realised she could earn more money working in the bindery at the Government Printing Office near Wellington Railway Station. She stayed there for nearly 20 years and in the process, lost much of her hearing.

I first met Jadwiga in 1969 and remember her coming home from work exhausted and falling asleep on the sofa. At weekends she would cook delicious meals; I especially remember her schnitzel and goulash. For a long time, communication between us consisted largely of her asking me whether I wanted something to eat.

Throughout the Champion Street years Jadwiga and Antoni scrimped and saved with the aim of buying their own home. This they achieved in 1973, when they moved into a newly built house in the new Porirua suburb of Ascot Park. It’s hard to imagine how they must have felt about acquiring their own modern home in a peaceful and prosperous country that was as far removed from the horror of wartime Poland as it was possible to get.

Antoni’s poor health eventually caught up with him. He suffered chronic emphysema and heart trouble and died after suffering a severe stroke in 1980. In his last years he worked as a messenger at the evening post, a job he seemed to love and where he was regarded with affection by the staff. Tata, as we knew him, was a people person, in contrast to Jadwiga, who was shy and reserved.

Jadwiga eventually moved in 1987 to Raumati, on the Kapiti Coast, mainly to be close to the three of her children—Wanda, Jolanta and Maryla—who had ended up living there. In the latter part of her life her priority was looking after Andrew, who suffered mental illness and was in and out of state care.

Sadly, Andrew died in 2013—the first of the siblings who pre-deceased their mother. We lost Wanda in 2014 and Halina two years after that.

No one can say how hard this was on Jadwiga, because she didn’t show her emotions. I often wondered whether the war years taught her that she couldn’t afford the luxury of dwelling on sadness and grief; she just had to push through it.

In her last years Jadwiga lived in Sevenoaks retirement village at Paraparaumu, but when her health deteriorated Jolanta arranged for her to move into Glenwood in Masterton, where she was only a short walk from our home. It was there that she died, quickly but peacefully. That she lived to 96 speaks of her extraordinary spirit and resilience.

I don’t know what else I can say about Jadwiga, because in some ways she was an enigmatic person. She could give the impression of being shy and timid, but she was strong-willed to the point of stubbornness and always knew what she wanted.

She was also smart and perceptive, whether it was in financial affairs or her grasp of politics and world affairs. One of the sad things about her last months was that her eyesight and hearing had faded to the point where she could no longer read the paper or watch television. Her favourite channel, incidentally, was Maori TV, which she always pronounced as Ma-ori.

She was a remarkable woman and I find it difficult to comprehend the breadth of the lifetime’s experience embodied in her diminutive frame, or the strength of the spirit that sustained her. If I had to choose a single word to encapsulate her life, it would be that she was a survivor.

© Karl du Fresne, 2019