KATYŃ -THE UNSPEAKABLE CRIME

by Barbara Scrivens

The murders of at least 21,857 Polish prisoners-of-war were clinical, brutal and carried out day after day in remote Russian locations in April and May 1940. In the Katyń forest, trees muffled the shots of the specialised executioners, Soviet NKVD officers. Their victims were mostly officers too.

Evidence gathered three years later from the eight mass graves in Katyń holding 4,243 Poles pointed to unerring marksmen. For decades, Soviet authorities hid other mass graves, such as those in Miednoje (Mednoye), Charków (Kharkov) and Piatichatki.

Mass graves in Miednoje held the remains of Poles imprisoned in Ostaszków and murdered in Twer (Tver). Mass graves in Charków and Piatichatki held the remains of Poles imprisoned in Starobielsk. In Katyń the gravesites were the murder sites of prisoners from Kozielsk. The Soviet NKVD dealt slightly differently with their prisoners in Ostaszków and Starobielsk. They led the Poles one at a time into cells, padded to muffle sound and with drains to divert blood, in groups generally of 250 and at night, to allow the removal of their corpses under darkness.

Each Polish victim’s skull showed the same bullet trajectory, from the base of the neck through to the forehead.

In Katyń, their remains drew the scenario that two Soviets held each of the Polish victims, to allow the third a clear shot. Shell casings found in the mass graves, and the arrangement of layer after layer of tight rows of corpses, indicated that their assassins positioned each captive’s head forward for the fatal shot as they hovered on the edge of a grave filling up with men in Polish uniforms.1

Not all the Polish victims stood quietly. Many had their hands tied with string, had their teeth knocked out, or revealed stab marks from a four-sided Russian bayonet. Some had their heads covered by coats, filled with sawdust and tied around their necks. Sand filled other open mouths.2

This photograph showing a Polish officer's hands tied with cord was one of the exhibits at a 1952 Congressional hearing into the 1940 Katyń murders.

Germans had occupied Smolensk since 19 July 1941. Polish forced-labourers first disturbed the graves in 1942. Sent to work near the Katyń forest by the German Todt organisation, the Poles inevitably chatted to Russian civilians living nearby, who eventually shared tales of the NKVD activity the previous spring. The Poles asked to see proof, confirmed the enormity, and left two birch crosses over the graves they unearthed.3

In April 1943, the same Russians led Germans to the gravesites, and Katyń, 16 kilometres west of Smolensk, began to give up its secrets.

The Germans grasped the propaganda opportunity. Their former Soviet ally had clearly committed this heinous crime, and on 13 April 1943, the Berlin Broadcasting Station announced that in “a place called Kosgory4 …a great pit was found, 28 metres long and 16 metres wide, filled with 12 layers of bodies of Polish officers, numbering about 3,000.”

The Allies greeted the news with “a vexed silence” throughout the next day.5

Forty-eight hours after the German broadcast, Stalin responded by blaming the Germans for the massacre, and concocted a story about Polish officers he had previously purported to know nothing about, having fallen into German hands during the summer of 1941.6 The same day, the BBC supported the Soviet lie, which by its continued repetition became embedded in British WW2 history.7

Unfortunately for the Polish nation, the discovery came at an awkward time. British and American commanders and diplomats well-knew of the 15,000 Polish officers missing in the USSR since April and May 1940, and had followed Polish attempts to find them. Polish commanders and diplomats, including Polish Prime Minister General Władysław Sikorski, had kept them informed of their meetings with their Soviet counterparts, including Soviet leader Joseph Stalin. But their British and American counterparts had ensured that until then “not a single detail had been published in the Allied press” apparently fearing the issue might cause “a split in the camp of the United Nations.”8

If Germany had not crossed into Russian-occupied Poland on 22 June 1941 and raced towards Moscow, those Polish graves, and others in western USSR, may have remained hidden. But Hitler did turn on Stalin, and the Germans did occupy western Russia, and Stalin, at a time of temporary military weakness, decided that he could use the Poles in his prisons and forced-labour facilities to help him defeat the German invaders.

As German troops approached Moscow’s outskirts on 30 July 1941, in London, General Sikorski and Soviet Ambassador to the United Kingdom Ivan Maisky signed a release agreement for the Poles in the USSR, which allowed them to form an army on Russian soil.

The Polish search for the missing officers started in September 1941. They had failed to arrive at any of the new Polish army’s enlistment stations in southern Russia. Stalin assured General Sikorski on 3 December 1941 that all the Poles in the USSR had been “set free” and shrugged that the officers were “probably in Manchuria.” That meeting included Stalin’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, Vyacheslav Molotov. Accompanying General Sikorski were Polish Ambassador to the Soviet Union in Moscow Stanisław Kot and Commander–in-Chief of the Polish Forces in the USSR Lieutenant-General Władysław Anders.9

In July 1942, the Kremlin, continuing to deny knowledge of the missing Polish officers, offered the Poles three scenarios: they had returned to Poland; they had escaped abroad; they had become casualties on the way to the recruiting stations during the Russian winter.10

The discovery at Katyń gave the Poles a definitive answer, but by April 1943, the dynamics of the WW2 conflicts had changed. By then, the Soviet Union had defeated the Germans in Stalingrad, was pushing them back out of Russia, and was of far more value to the Allied cause than Poland, an occupied country whose armies operated outside its borders and that had to buy all its military ordnance from others.

General Sikorski’s government approached the International Red Cross in Switzerland to investigate the Katyń find, as did the Germans, but the IRC refused to do so without Soviet approval, which it did not receive. The IRC published its decision not to become involved in the matter on 23 April 1943, two days after the Soviet newspaper Pravda published an article accusing the Polish government of collaborating with Hitler.11

Exhibit 98 of the 1952 Congressional hearing into the 1940 Katyń murders, showing the sparse wood surrounding one of the mass graves, then still an exhumation site.

By May 1943, the Soviets openly declared that they intended to hold on to the part of Poland they had invaded as Hitler’s partners, and had formed a Union of Polish Patriots to administer it.

By then, Stalin held a significant number of Polish men in the Red Army, and a Soviet-controlled Polish army under the Polish deserter Zygmunt Berling. Conscription into the Soviet sympathiser’s cynically named 1st Tadeusz Kościuszko Infantry Division started in September 1942, immediately after the second mass evacuation from the USSR—via the Caspian Sea— of nearly 70,000 Polish military and civilian evacuees. It caught those who had not managed to escape the USSR with the genuine Polish army.12

In April 1943, Churchill was more preoccupied with the battle in Tunisia than the discovery at Katyń, more intent on appeasing Stalin than respecting General Sikorski. Despite British pressure to withdraw his IRC request, Sikorski refused.

General Sikorski’s request for an international inquiry gave Stalin the excuse to break off the tenuous diplomatic relations resumed with Poland in July 1941. Churchill and United States president Franklin Roosevelt made their joint stance backing Stalin clear: Poland’s losses were historical and therefore irrelevant, while the threat from Germany was imminent and needed stopping at any cost.

On 24 May 1943, British ambassador to the Polish government-in-exile Sir Owen O’Malley sent a confidential despatch to British Foreign Secretary Sir Anthony Eden. The report dealt with O’Malley’s investigations into the disappearance of the Polish officers in the USSR, the find at Katyń, and the “almost certainty of Russian guilt.”13

On the covering minutes, a D Allen wrote “while recognising the present necessity to avoid public accusations of our Russian allies… we should at least redress the balance in our own minds and in all our future dealings with the Soviet Government refuse to forget the Soviet crime of Katyn.”

An FK Roberts wrote, “It is obviously a very awkward matter when we are fighting a moral cause and when we intend to deal adequately with war criminals, that our Allies should be open to accusations of this kind and to others relating to the deportation of hundreds of thousands of Poles and to their subsequent treatment in Soviet Russia. However, as Mr O’Malley says himself, there is no point in assisting German propaganda on these issues and there is no reason why we cannot maintain our own moral standards and values whilst at the same time endeavouring in every way possible to improve our relations with the Russians…”

Another covering note from a W Strang suggested that only King George VI and the War Cabinet receive O’Malley’s report. “It is a powerful piece of work and deserves to be read.”

On 4 July 1943, General Sikorski died in a suspicious aeroplane crash as he departed Gibraltar. He had been on his way back to London after a tour of Polish forces and speaking engagements in the Middle East. Churchill told the Polish nation in a broadcast on 14 July 1943: “Soldiers must die…”14

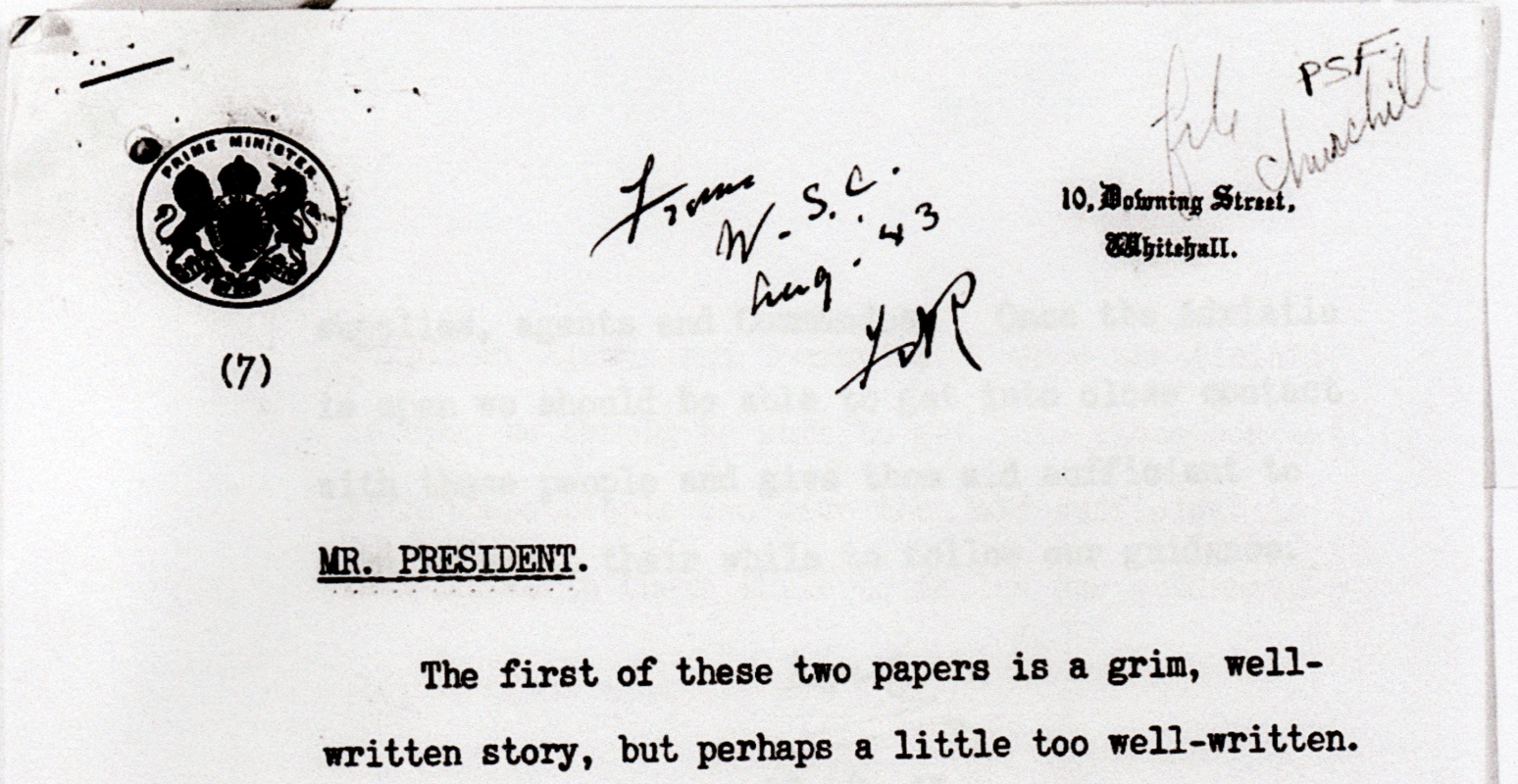

Churchill’s August 1943 covering note to Roosevelt explaining Sir Owen O’Malley’s enclosed report on Katyń.

A month later, Churchill sent O’Malley’s report to President Roosevelt. Churchill’s covering letter opened with the remark, “The first of these two papers is a grim, well-written story, but perhaps a little too well-written. Nevertheless if you have time to read it, it would repay the trouble. I should like to have it back when you have finished with it as we are not circulating it officially in any way.”

In 1944, Roosevelt asked George Earle, then his special emissary to the Balkans, to investigate, but refused to accept Earle’s finding that the blame for the Katyń massacre lay with the Soviet Union. On 24 March 1945, Roosevelt expressly forbade Earle from publishing anti-Russian material, and banished him to American Samoa.15

Even after Stalin died in 1953, successive communist leaders in Moscow and their successive puppet governments in Poland strove to delete from history the mass murders, in Katyń and elsewhere, of thousands of Polish military and civilian elite.

Katyń became a prohibited word in communist-controlled post-war Poland, officially forbidden, whispered only between the closest and most trusted of friends and family. Its utterance within earshot of a communist sympathiser, or in public, could lead the speaker to police interrogation and jail.

Stalin’s plan to physically remove Poland’s intellectual elite did not take into account the memories they left behind. Families, friends and acquaintances knew their loved ones had left to protect Poland in time of war, or had witnessed their arrests. Many families had received cards from them, written in prisoner-of-war camps in western Russia: Kozielsk, Starobielsk and Ostaszków.

The murdered men’s families never forgot. They may have thought their questions would be answered on the 50th anniversary of the crime when Mikhail Gorbachev, the eighth and last leader of the Soviet Union, conceded Moscow’s guilt and handed Polish President Wojciech Jaruzelski documents on Katyń that were “recently found in the security archives—in a place almost no-one thought to search until now.”16 Those documents included information of two other prisoner-of-war camps at Starobielsk and Ostaszków, but not the whereabouts of thousands of other Polish men arrested in 1939 and 1940.

Russian records showed that in September 1939, the invading Soviet army captured 227,454 Poles, including 10 generals, 52 colonels, 72 lieutenant-colonels and 5,131 officers of lower rank. Most were in the army reserves, but they included 200 pilots. In private life, they were priests, university professors, physicians, lawyers, engineers, teachers, writers and journalists. This number did not include the police force, the military police, or members of the Frontier Defence Corps. Many were never heard of again.

Gorbachev’s spirit of glasnost did not include his releasing the death warrant that Stalin signed on 5 March 1940.17

Its instructions were specific. The USSR NKVD was ordered to “give special consideration to 14,700 people” in Soviet prisoner-of-war-camps, and another 11,000 “arrested and remaining in prison” in western Ukraine and Byelorussia, “imposing on them the sentence of capital punishment—execution by shooting.”

The order stated that more than 97 percent of the “people” concerned were Polish, and described 14,736 in the prisoner-of-war camps as former Polish government officials, landowners, policemen, intelligence agents, military policemen, settlers and jailers. It classified the other 11,000 as members of various counter-revolutionary spy and sabotage organisations, former landowners, factory owners, former Polish army officers, government officials and defectors. The “cases [were] to be handled without the convicts being summoned and without revealing the charges; with no statements concerning the conclusion of the investigation and the bills of indictment given to them.”

Stalin had to say no more. His NKVD executioners stepped up to make his wish a reality.

_______________

Jan Turkiewicz grew up in Kraków, under the Katyń cloud. Born in Jagielnica in 1938, in then-eastern Poland, the family moved north to the larger town of Czortków where his father, Józef, managed a cigarette factory.

“The NKVD arrested my father on his name’s day, 19 March 1940. He was 30. We had guests at home to celebrate and he was in [his officer’s] uniform. They arrested him, and he was gone. We never saw him again. Mother looked everywhere but there were no messages from him, none. She found a friend of his, who had been in a prison camp with him, but he left that camp and no one came back.”

Józef Turkiewicz, with his wife, Danuta, centre, his mother, Helena, and his sister, Ludmiła during a visit in 1936 to Józef’s parents’ home in Janów Lubelski, south of Lublin.

“My father was highly educated and in those days in Poland, men with higher education became officers in the army. When the NKVD arrived at our house, they knew everything about him. My father knew exactly what was happening. He knew he would not be back. He took off his wedding ring, gave it to mum, and said, ‘I give you your freedom back.’

“I don’t remember my father, but my brother was always talking about him. His name was Józef Mieczysław. Mum called him Miecio.”

After her husband’s arrest, Jan’s mother, Danuta, fled to her parents’ home in Lwów with Jan and her older son, Andrzej. Two years later, the death of her father, the renowned professor Józef Switkowski, forced her to move to Kraków. Without his protection, she felt vulnerable to the increased threat of Ukrainian paramilitary organisations bent on their own brutal ethnic cleansing of Poles in Wołyń and eastern Galicia. Danuta knew she would get support from her father’s friends at Kraków’s Jagellonian University, and soon felt at home in the university city. She had a degree in music and another from the in Paris, and after the war made a living importing horses for transport and farming, and painting.

“In Poland, after the war, lots of kids lost their parents, a mother or a father or a grandfather… especially when I was young, everyone was asking, ‘Who is your father?’ ‘Who is your mother?’ Every kid wants to know—it is a basic instinct—a person wants to know where he comes from, and I didn’t know who was my father.

“My mother never stopped looking for him, and she never remarried. She wrote to Russia and the States, all over the world, and nobody could tell her what happened to him. In Poland at the time, [under] the communist system, nobody talked about Katyń. We knew about it, other people knew about it, but talked only in secret, never in the open. People were very wary. You could not trust anyone. There was nothing about Katyń in the media, on TV, no books, nothing. You could not talk about Katyń, in the same way you could not talk about celebrating 3 May, the Polish constitution. Police in Poland at this time were never ‘the beat on the street,’ they were always behind doors, and sometimes people never come back [from ‘visiting’ a police station].”

Jan Turkiewicz now lives in Whangaparaoa, north of Auckland. He met his wife, Urszula when both worked as engineers at Fabryka Maszyn Papierniczych (FAMPA), a paper machine factory that operated 24 hours a day in Cieplice. Jan’s additional position as customs export officer inspired him to plan their escape from Poland under the pretence of going on a holiday to Venice. At that time, the police held everyone’s passports, and their ability to leave was so tenuous that they told only three people of their true plans to seek asylum in New Zealand.

Knowing that at the border, police would search them, their car and all their belongings, Jan squeezed important documents into the car’s radio, which he made sure still worked. Within earshot of the border police, he and Urszula spoke only of their fictitious holiday plans. They left Poland on 4 September 1981, with their daughter, Roma, then five. Three months later, the communist-controlled Polish government introduced martial law in an attempt to crush the growing Solidarity trade union.

As a new refugee in Austria, Jan could barely believe his eyes when he saw the word KATYŃ printed in block letters on a book cover in a newspaper kiosk.

“I looked for my father 41 years, and I found him in this refugee camp, in the book. It was a German book, but at the end was a list in the Polish language… names from the camps in Ostaszków, Starobielsk, and Kozielsk. I don’t speak German, but I found this book and it had this list in the Polish language, and I found my father, his name, documents, everything.”

Digital records have less information. Józef Mieczysław Turkiewicz is listed in the Karta Indeks Represjonowanych as being arrested by the NKVD in 1940 but there all trace of him seems to end.18

Jan regrets allowing someone to borrow his book in Auckland, because he has not seen it since. His father’s entry, however, remains indelible in his mind.

With other Poles in Auckland, Jan fought for a permanent Katyń memorial in New Zealand’s largest city, and campaigned for a commemorative plaque. The Bishop of Auckland unveiled it at the Auckland Catholic Cathedral on 16 April 1990, three days after Gorbachev, in Moscow, handed Jaruzelski the lists of those executed at Ostaszków and Starobielsk. (St Mary of the Angels church in Wellington accepted a similar plaque in November 1977.)

Bishop of Auckland Denis Browne blessed and revealed the plaque in the Auckland Catholic Cathedral on 16 April 1990.19

_______________

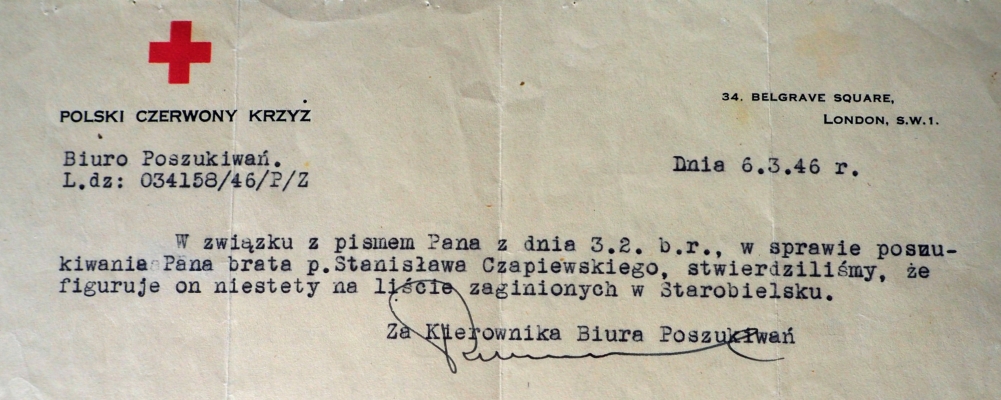

Teresa Miotk, now living in Auckland, has two sets of documents, which give two official versions of what happened to her uncle, Stanisław Czapiewski, after her mother last saw him on 7 September 1939.

The Polish Red Cross in England confirmed his name on a list of Polish officers missing in Starobielsk. The Red Cross in Russia said he had not been in the USSR at all.

Stanisław Czapiewski worked as an editor at the Kurier Poznański when he was mobilised and sent to follow the Polish army as it created an eastern front against the Germans. In the wake of the Russian invasion on 17 September 1937, that front did not materialise. This photograph was taken in 1937.

Teresa does not know by what means her mother, Zofia, received the documents—her mother refused to talk to her about anything to do with WW2—and all Teresa has is the information written on them.

In 1946, the Polish Red Cross based in London confirmed to Zofia’s brother, living with her parents in Baltimore, USA, that Stanisław was on the list of the “missing in Starobielsk.” Knowing of the strict censorship in post-war Poland, her family in the USA may not have wanted to take the risk of writing to tell Zofia: interception of such a message would make her and the rest of the family a target of the UB (Urząd Bezpieczeństwa), the secret police that operated under Poland’s communist-controlled government.

The Polish Red Cross based in London sent Eugeniusz Czapiewski, living in the USA, confirmation that his brother Stanisław’s name appeared among those missing from the NKVD’s Starobielsk facility.

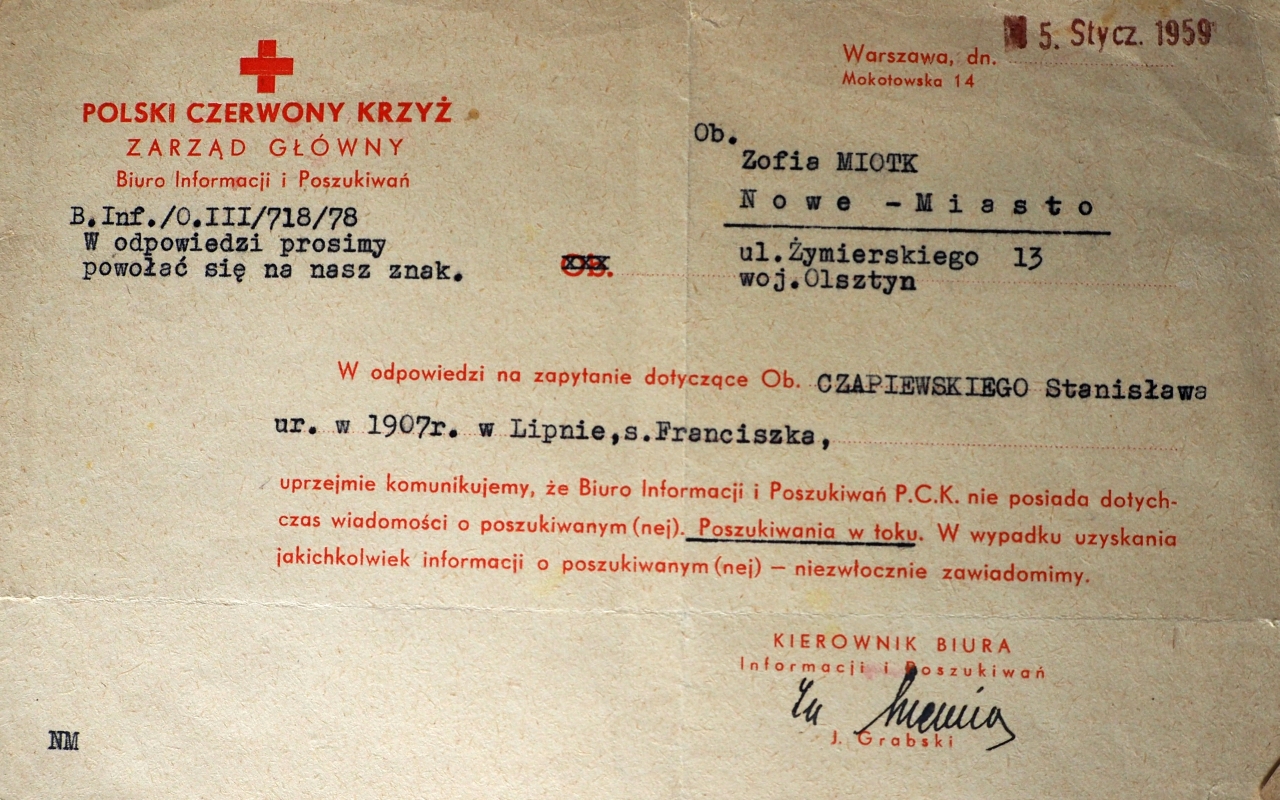

Thirteen years after Stanisław had been listed as missing in Starobielsk, Zofia received a form letter from the Polish Red Cross’s head office in Warsaw, saying it had no news about the searched-for person. They would inform her “immediately” they had any information.

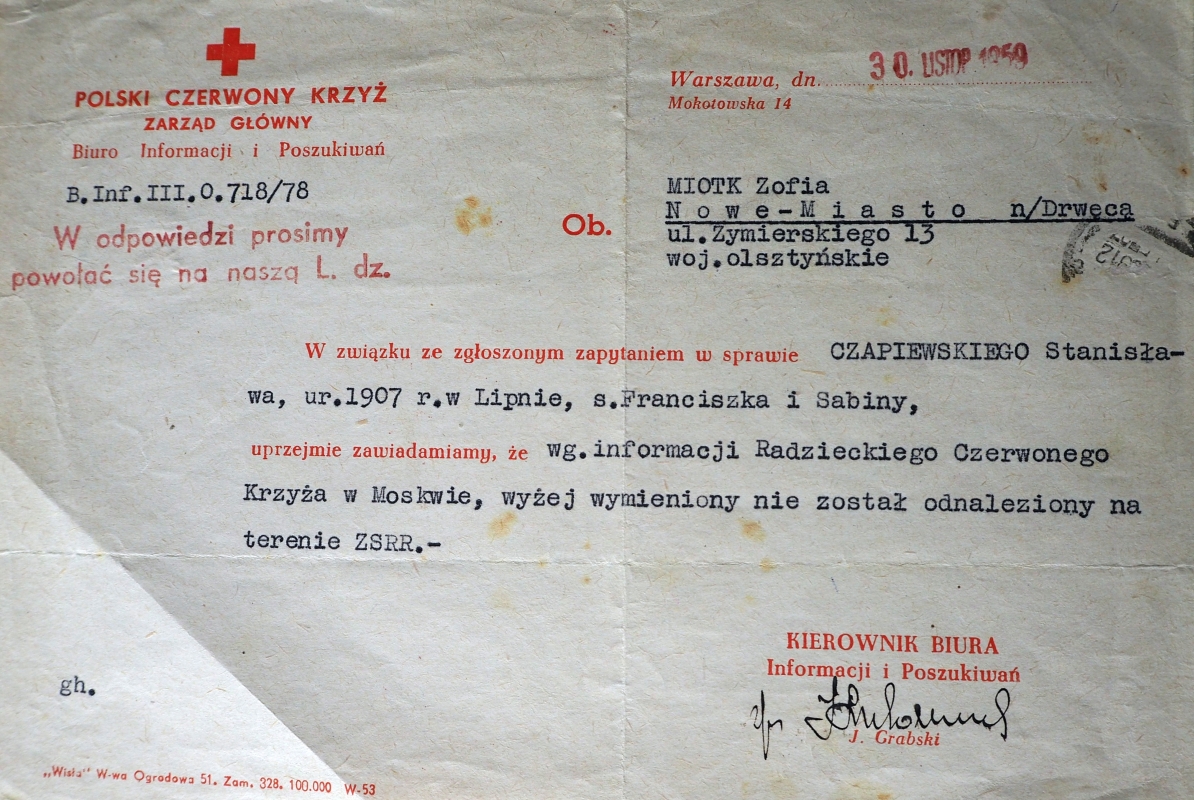

Nearly a year later, in November 1959, the same office forwarded Zofia a notice from the Red Cross in Moscow saying that her brother was “not found in the USSR.”

Teresa believes that her grandparents received the information from London because they lived in the United States. Franciszek and Sabina Czapiewski, with their youngest son, Eugeniusz, immigrated there from Lipno just months before Germany invaded Poland in 1939. (“My grandfather didn’t plan on the Second World War.”) They left behind their only daughter, Zofia, and three other sons. Zofia had recently married Jan Miotk, and moved to Warsaw. Stanisław, Zofia’s older brother, had made a reputation for himself as a political journalist in Poznań, and worked for the news and political journal Kurier Poznański. Tadeusz, younger than her, ran his own business in Lipno. Kazimierz had recently finished high school and moved in with his sister and new brother-in-law.

“My mum met my uncle at the Warsaw railway station on 7 September 1939. He was mobilised and they were sending him east as an army correspondent. Because Germany came in from the west, the north and the south, the Polish government decided that they would concentrate soldiers along an eastern line, to stop the Germans invading from the east as well. They did not know that Russia was going to invade from the east.

“It was the last time she saw him. He saw how much Warsaw was bombed. She told me that he took out a very expensive fountain pen, a gift, and wrote something down. My mum promised my uncle that he would be her first child’s godfather. That’s why my brother never had a baptism. She kept waiting for my uncle to be the godfather; she kept the hope that he was living, that they would find him.”

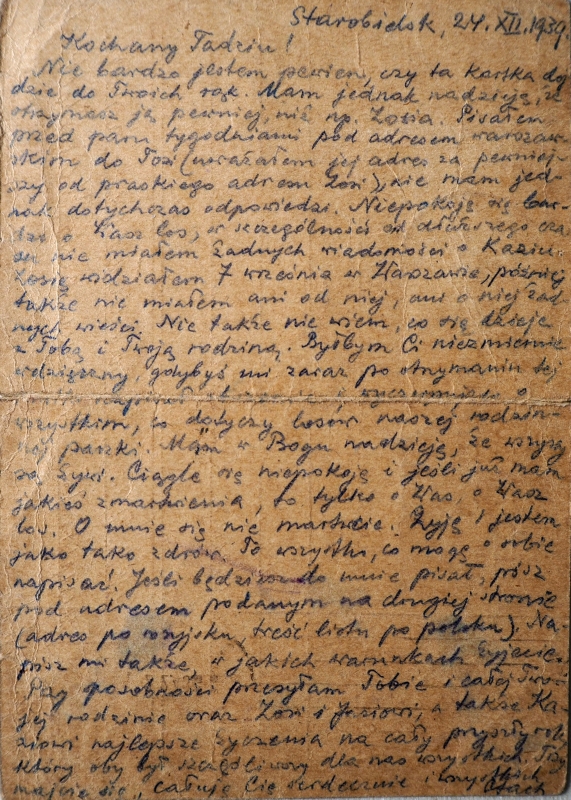

On Christmas Eve, 1939, Stanisław wrote to Tadeusz from the Starobielsk NKVD prison camp. Tadeusz still lived in Lipno, then under German occupation, and the card arrived via Berlin. Stanisław said he was not certain that Tadeusz would receive the card, but that he had a better chance at receiving it than Zofia, from whom he had not heard since he last saw her. He asked for news about the family, and said that he was afraid for them. They should not worry about him. He was alive, almost healthy, and explained that if they wanted to write, they should address the letter in Russian and use Polish for the content.

The German occupiers of Warsaw allowed Zofia one letter a month through the Red Cross, of around 50 words, including the addresses. Teresa has two of the cryptic cables from her grandfather, written to her mother in English through the American Red Cross. One, sent in September 1943, arrived in Warsaw the following May, and another, sent in December 1943, arrived in July 1944. The first was happy about Teresa’s birth and both ask for news of Stanisław.

Teresa, born in 1943, remembers nothing of the war. She knows that a German soldier ordered her mother, with her as a baby and her toddler brother, out of their Praga apartment during the 1944 Warsaw Uprising. Her policeman father and her uncle Kazimierz, both in the Polish Underground (the AK, Armija Krajowa), were not at home.

“She had to leave everything in the apartment. We had no documents, no photographs, nothing. This passport [of her grandfather] and photo [of Stanisław] and papers I have now are from when my mum visited my uncle in America.”

After the Germans removed Zofia and her children from their Warsaw apartment, they lived among various family members until they could reunite with Jan, who had been arrested. Years later, Teresa’s aunt in Kaszuby let on that Jan Miotk’s legs were so swollen when he returned from prison, she believed he was only let out because his captors did not think he would survive.

“After he came back from prison my mum was afraid for us. I finished high school in the ’60s. During all my schooldays, I had no information about what happened in east Poland during the war, what happened with the people taken to Siberia. After the war, my parents tried to falsify everything about their former life. Information was a danger. I knew that my uncle was a journalist, that he was a famous person, but my mum and my father told me he was lost during the Second War, probably in the ‘east.’ They never told me the truth.

“I tried to talk with my parents about it, but they didn’t want to. My mum was probably afraid to give me information, because if I have that information, and I say something to other people in school, it was danger for me, and it was danger for my family.

“Even when he was very old and I tried to ask my father about the war, or asked him to write down a memory, he said no. He never wanted to talk. He never told me what he did in the Polish Underground, and neither did my uncle.

“In ’59 I was in Russia, in a scout camp, and we found out information from the West, secret information, I don’t remember exactly how, but we knew it was dangerous to say anything.

“I remember mum cried talking about it. Many times, she tried to ask [Polish authorities] about her brother. She even she wrote to the Red Cross in Geneva, and even in ’59 they said, ‘We are looking till now.’”

The puzzle of what happened to Stanisław’s fountain pen may lie in the USSR’s State Jewellery Trust, which in 1940 sent buyers to the NKVD prison camps. Wrist watches apparently commanded a “good price,” pocket watches less, but they paid 20 roubles for any type of fountain pen.

“Many officers, although hard pressed, refused for sentimental reasons to part with personal objects. Frequently the officers would pool their roubles, make purchases [from a travelling camp store] and divide the goods among their roommates, whether they had contributed to the pool or not.”20

In April 1940, the NKVD did not bother stripping the Polish corpses of valuables or personal papers. One Russian, Alexander Jegorov, permanently employed at the Katyń exhumation site in 1943, stole “anything of value.” The Germans caught him with gold coins and rings, and shot him.21

_______________

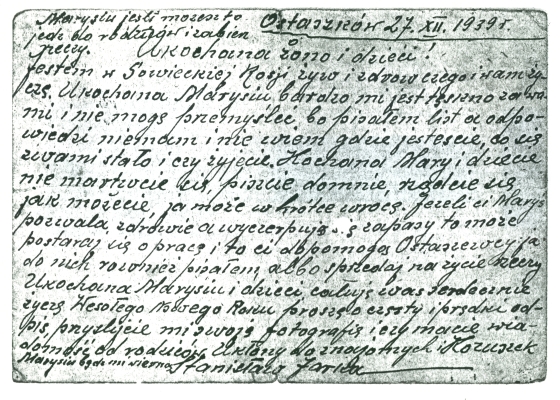

Jan Jarka and his older sister, Jadzia Jarka Cooper, arrived in New Zealand in November 1944, aged 14 and 17, knowing exactly where their father had been on 27 December 1939—the NKVD prison in Ostaszków.

Jan spent his life hunting for official recognition of their father’s fate. Two years after his death in 2008, his widow, Stella, received a commemorative booklet marking the 70th anniversary of the Katyń murders, which listed the 55 officers from the Ostrołęka area. Stanisław Jarka’s entry: Zamordowany przez NKWD strzałem w tył głowy w Twer, w 1940r. (Murdered by the NKVD, shot in the back of the head in Tver in 1940.)22

For more than 51 years, Stanisław Jarka’s remains lay in one of several mass graves hidden in a birch forest in Miednoje, a village outside Twer (formerly Kalinin) where the KGB later built holiday homes for its officers, and where the NKVD murdered nearly 7,000 inmates from the Ostaszków prison. There, the NKVD held mostly policemen, military police, and soldiers from the Polish Frontier Defence Corps, and also lawyers, public prosecutors and landowners.23

In August 1991, Vladimir Tokaryev, a retired NKVD officer who still lived in Miednoje told Colonel Aleksander Tretetsky of the Soviet Prosecutor’s Office exactly where to dig for the Polish remains. Tokaryev insisted that he had been “obliged to help them by putting my men at their disposal” but that he had not been in the “execution room.”24

Tokaryev explained the German shell casings found in the mass graves: The NKVD marksmen had brought with them “a whole suitcase full of German revolvers, the Walther 2 type. Our Soviet TT weapons were not thought to be reliable enough. They were liable to overheat with heavy use.”25

In Miednoje, the NKVD led the Poles brought from Ostaszków along a corridor “one by one” into a rest room for prison staff. Each man had to give his name and place of birth, before being led to a soundproofed adjoining room, where he was shot in the back of the head.

The 300 Poles shot the first night “was too many, because it was light by the time they had finished and they had a rule that everything must be done in darkness.” The NKVD reduced the number to 250 a night, and finished their assignment during April 1940. Tokaryev described the chief executioner, Vasily Blokhin, dressing for the job in a “brown leather hat, brown leather apron, long brown leather gloves reaching above the elbow” and ensuring that everyone in the execution team had a supply of vodka after each night’s shift.26

Stanisław Jarka, born in 1902, moved from Pokrzywnica to Białystok when he joined the city’s police force.

Stanisław Jarka had worked as a senior detective for the state police in Białystok. After the German invasion of Poland’s western borders, the Białystok mayor left with instructions to Stanisław and a “handful” of others to keep “superficial care” of the city, and to burn any tactically significant documents.

His daughter, Jadwiga Jarka Cooper, now lives in Orewa, north of Auckland. Her last sight of her father is seared in her memory. He arrived home unexpectedly during the day, riding a police motorcycle and wearing an army major’s uniform.

“I remember father running along the garden path calling our names. We came out, and he grabbed us, dropped down, and hugged the two of us, and stepmother. He said, ‘Take care, I shall write to you as soon as I can,’ and then, ‘Goodbye.’ He didn’t even turn off the motorcycle.”

He stayed long enough to explain to Jadwiga, Jan, and his wife Maria that if the Germans captured him, he was to keep his career in the police force a secret, and pretend that before the war he had been a shoemaker, or any kind of labourer. Unaware of Stalin’s plan to invade Poland, Stanisław and other state employees from Białystok drove east.

“Wherever they stopped, they met Russians. One day they were ‘invited’ to leave their knapsacks and go into a canteen to eat. Their knapsacks were confiscated and they were taken to Kozielsk.”

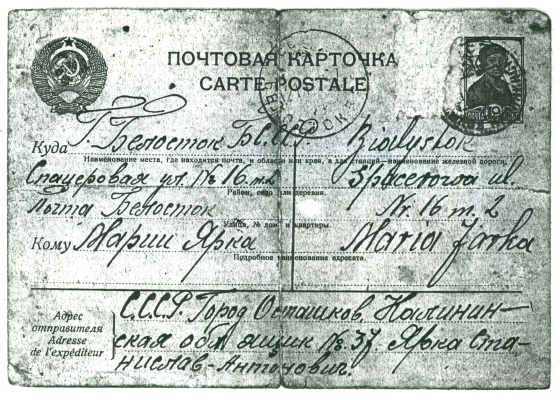

Stanisław wrote postcards to his family from the NKVD prison in Kozielsk, then Ostaszków, but even after the censored postcards confirming his incarceration in the USSR started arriving, Soviet soldiers routinely searched his Białystok home for him.

Jadwiga: “They always came in the middle of the night, surrounded the house, and kept asking us, ‘Where is your husband? Where is your father?’ They must have known they already had him.”

Stanisław wrote his last postcard to them on 27 December 1939:

Stanisław tells Maria that he is in Soviet Russia, alive and well, and wished her the same. He longs for them all and cannot comprehend why he has not had an answer to the letter he wrote. He does not know where they are, what has happened to them, or if they are still alive. He begs Maria to write to him, manage the best she can and, if her health allows and provisions are getting depleted, to possibly get a job or sell their things to pay for day-to-day living.

He addresses Maria as his beloved, sends her affectionate kisses, wishes them all a happy New Year, asks for photographs and for news of his parents and other acquaintances. According to the code he worked out with Maria before he left, his mention of Kożuszek (his sheepskin coat), indicated that his situation was dire.

Soviet soldiers removed Stanisław’s family from their Białystok home in April 1940, the same month that the NKVD executed him, and thousands of others covered by the death warrant that Stalin signed on 5 March 1940.

Jadwiga: “They came at night—again surrounded the house so nobody escapes—thumped on the door. This time they came in brutally, and demanded, ‘Get dressed, get the children… Hurry, hurry, hurry.’ It was all very military. Everything was in a hurry, because it was a secret. They did not want others [in the street] to know what was happening to us.”27

The Soviet soldiers bundled Stanisław’s family onto a truck bound for the city railway station, then onto a cattle train, to a kolkhoz in northern Kazakhstan. Jadwiga and Jan survived, escaped the USSR in 1942 with the help of a Polish army formed in Russia, and arrived in New Zealand with 731 other Polish children and their 105 caregivers.

Jan Jarka spent his life in service to the Auckland Polish community in particular, and lived by the motto Vanquish Evil by Doing Good (Zło Dobrem Zwycieżaj). In 1989, then Prime Minister David Lange convinced Polish-speaking Jan to take up a Justice of the Peace role to help new Polish immigrants and other ethnic minorities deal with English-speaking New Zealand authorities. In June 1993, Jan received a Queen’s Service Medal for his work.

_______________

The NKVD executed Second Lieutenant (reserves) Józef Rubisch in Katyń on 14 April 1940.28 He was born in Rzeszów, fought in WWI and the 1919–1920 Polish-Soviet war, and graduated from the State Dental Institution in Warsaw in 1924. According to the Karta Indeks Represjonowanych, he was among those exhumed in the Katyń forest by the German army in April–June 1943.29

Wisia Schweiters, his niece, born in 1931, was among the members of the Auckland Polish Association who fought for a memorial plaque to honour his death, and the deaths of other Polish men murdered in the same way.

In September 1939, a friend of Wisia’s father, Zygmunt, urged him to leave Nisko, where the family then lived, because the occupying Germans had found out that, before their invasion on 1 September 1939, Zygmunt had reported seeing German spies at a Polish ammunitions factory. The family moved to relatives in Lwów, then already occupied by the Russians.

In a 2016 interview,30 Wisia recalled her parents receiving a letter from her grandmother to say that Zygmunt’s older brother, Józef, had been arrested by the NKVD, and was being kept near Katyń. Another letter from her grandmother asked Zygmunt to return home because she was ill.

At that time in Lwów, the Russians encouraged Poles who wanted to return to Germany to make themselves known. Zygmunt did, not expecting to be confronted instead with the question of whether he was willing to take Russian citizenship. He refused, and as soon as the Russian officers told him they would “be in touch in the next few days,” Zygmunt knew he needed to hide. When Soviet soldiers came looking for him, he ran to the attic, but made himself known when he heard the soldiers say they would in any case take away his wife, Anna, Wisia, and his son, Ignacy.

“My mum was flurried. Auntie packed. The officer told her to take warm clothes. We were taken to a train station, to a train surrounded by Russian soldiers. We got put into a boxcar, so full that you couldn’t move.”31

In April, June and July 1940, using 19 cattle trains, Soviets removed more than 25,000 Poles from Lwów to mostly southern Russia and Kazakhstan. Ignacy did not survive. After the July 1941 Polish-Soviet agreement to release the Poles in the USSR so that they could form an army on Russian soil, Zygmunt enlisted. He escaped the USSR with that army in 1942, and so did Wisia and her mother, who spent the next two years as refugees in Isfahan, in then-Persia (now Iran). They arrived in New Zealand in November 1944 with 836 other Poles who escaped the USSR the same way.32 Zygmunt Rubisch joined them in June 1947, arriving in New Zealand on the SS Rangitiki with several other husbands of staff at Pahiatua.

Wisia still remembers visiting the Katyń forest with Maria Grabkowski and the Reverend Monsignor Zdzisław Peszkowski, who escaped execution in Katyń in 1940. He was among 432 Polish officers whom the NKVD diverted to a single legitimate prisoner-of-war camp in Griazovec.33 Monsignor Peszkowski spent the rest of his life dedicated to the memory of his friends and fellow Poles murdered in Katyń, and became chaplain of the Katyń and Murdered Families of the East. He gave Wisia the pine cone and soil from Katyń that rests in the centre of the plaque.

Wisia: “It was quite horrific to be near it all, in the forest, the trees… painful. I remember the house by the garden where the officers were before they were taken out and shot. But there has never been hatred in our hearts. There has been pain and prayer, but not hatred.”

Polish officers visiting Auckland in April 2018, Colonel Paweł Chabielski, Commander of the Kielce Garrison, and Lieutenant Colonel Marcin Matczak paid their respects to the Polish officers killed in Katyń during an annual commemoration by Auckland Poles.34

_______________

Jerzy (Jarosław) Popławski, a captain in the Polish reserves when Germany invaded Poland on 1 September 1939, helped people escape from German-occupied Warsaw, to Russian-occupied eastern Poland. The German blitzkrieg had left street after street in the central city bombed and burning.

The Polish garrison in Warsaw surrendered on 26 September, and when German troops entered the city the next day, more than 20,000 civilians had died. Those remaining who could, fled towards eastern Poland, where many Warsovians had family.

Jerzy’s son, Zbigniew: “It was thought at the time that that was the better of the two evils.” Zbigniew, now living in Timaru with his wife, Valerie, was born in Warsaw 10 months before the German invasion. Zbigniew’s mother was Kazimiera (Kazia), the youngest of three daughters, whose family name was also Popławski. Her father, Jan, one of two sons and seven daughters, ran the family estate in Janopol, near Międzyrzecz, about 100 kilometres east of Białystok. The district’s civic centre, Wołkowysk, was a rail hub for lines running north-south and east.

“The Russians apprehended us while we were sneaking from Warsaw to Janopol and imprisoned my father. We never saw him again.

“Our name was on the Russian deportation list for three reasons—my father’s position as a banker and an officer in the reserves, and my mother’s family’s long history of anti-Russian resistance. Her grandparents and their family had previously been deported to Siberia, and her father had fought against the Russians in WWI.”

Jerzy (Jarosław) Popławski remains on the list of the missing men arrested by the Soviet NKVD in eastern Poland in 1939.

Kazimiera and infant Zbigniew managed to get to the Janopol estate, where they remained until April 1940, when the NKVD started rounding up the families of the men they had arrested. Soviet soldiers, barging into their farmhouse and ordering them to pack and leave, gave Zbigniew’s grandmother, Zofia, a heart attack, and she died. Kazimiera was away from home that night, helping her older sister, Janka.

“My mother and I became permanently separated and from then on, I was looked after by my aunt Jadwiga, including later in Persia and in New Zealand. She had two sons, Wojtek about two years older than me, and Franciszek, younger. We were deported to Kazakhstan in the second wave in April 1940.35 There were 14 of us, seven from the estate and seven from the immediate neighbourhood.”

A schedule of the NKVD rail transports shows that on 16 April 1940, a cattle train left Wołkowysk with 1,443 Polish captives, guarded by the 11th brigade of the Red Army’s 236th regiment, and bound for Tajncza, Siwierokazach.36 Unlike the mass expulsions of Polish civilians in February 1940, which included entire families and many able-bodied men able to work in NKVD forced-labour facilities in northern Russia and Siberia, the later transports seemed to have no purpose other than to remove from eastern Poland the families of the thousands of Poles previously arrested and captured by the Soviets.

The train carrying the Popławskis deposited them in northern Kazakhstan, and left them to fend for themselves. The only means of survival was through finding work in the already subsistent kolkhozes.

Zbigniew: “Fourteen of us lived in a mud hut. The adults and older children were expected to work in the crop fields.”

Zbigniew’s younger cousin, Franciszek, died there of dysentery. His grandfather, Jan, survived that disease, but died of pulmonary TB in then-Persia once the family had escaped the USSR with the Polish army in 1942.

Even after the Polish-Soviet agreement of 30 July 1941 that allowed them to leave, the conditions for the Polish civilians remained miserable. In a report regarding the surprising lack of Polish officers enlisting in the Polish army, British War Office liaison officer for the Polish army, Lieutenant Colonel Leslie R Hulls wrote on 18 June 1942, “Families, chiefly without men are expulsed to distant localities without the right of leaving their place of residence. They stay there bewildered… without any financial means, without assistance and without food.”

Zbigniew: “After many weeks of travel, we managed to leave the USSR. We reached Krasnovodsk and crossed the Caspian Sea into Persia in a dilapidated, rusty old tanker with standing room only. It was packed shoulder to shoulder. I think it was the last such transport before Stalin changed his mind and ‘shut the gate’ [in September 1942] so we were very lucky.”

Kazimiera Popławska remained in Poland, later remarried, and died in 1964.

“I was a penniless student and unable to find the money to travel to Poland to see her until it was too late. I was in the process of arranging travel, thanks to my future father-in-law, when we were notified that she had died and was already buried.”

Zbigniew grew up understanding that his father had been imprisoned in one of the NKVD-run mines in far-north Siberia37 but years later, relatives in Garwolin contacted him to tell him he had been killed in the Katyń massacre.

Zbigniew’s aunt, Jadwiga Michalik, who died in 1998, guided him towards a medical career. He qualified as a doctor in 1966, and then trained to become an orthopaedic surgeon. Although retired from full-time practise, Zbigniew still works one week a month in Australia, assessing people with permanent impairment, and providing them with medico-legal reports.

Stalin may have thought he could remove Poland’s intellectual elite, but he could not stop the generations that remained.

© Barbara Scrivens, April 2020.

THANKS TO POLISH AMBASSADOR TO NEW ZEALAND, ZBIGNIEW GNIATKOWSKI, FOR INITIATING THIS STORY.

THANKS TO THE NORTH AUCKLAND RESEARCH CENTRE IN THE TAKAPUNA LIBRARY FOR THE LOAN OF AUDIO RECORDING EQUIPMENT.

THE PERSONAL PHOTOGRAPHS AND DOCUMENTS ARE FROM THE PERSONAL COLLECTIONS OF THE TURKIEWICZ, MIOTK, JARKA AND POPŁAWSKI FAMILIES.

If you would like to comment on this, or any other story, please email editor@polishhistorynewzealand.org.

ENDNOTES:

- 1 - Mackiewicz, Joseph, The Katyń Wood Murders, pages 154 & 160, Hollis & Carter, London, 1951.

- 2 - Ibid, page 161.

- 3 - Ibid, page 91.

- 4 - Kosgory, or Goat Hills, is the specific section of the Katyń forest that held the mass graves.

- 5 - Ibid Mackiewicz, page 91.

- 6 - Ibid, page 92.

- 7 - The Second Great War; A Standard History, Volume 7, pages 2,735 & 2,935. Sir John Hammerton edited the nine-volume set, and Major-General Sir Charles Gwynn acted as military editor. The Waverley Book Company Ltd, in association with The Amalgamated Press Ltd, London. The volumes have no publication year.

- 8 - Ibid, Mackiewicz, pages 89 & 87.

- 9 - Anders, Władysław, Lieutenant-General, An Army in Exile, page 85, reprinted by The Battery Press, Inc, Nashville, 2004.

- 10 - Ibid Mackiewicz, page 86.

- 11 - Ibid, pages 100 & 101.

- 12 - Ibid, Anders, pages 195 & 196.

- 13 - The British government declassified the report in December 1972.

- 14 - Irving, David, Accident; The Death of General Sikorski, page 10. William Kimber & Co. Limited, London, 1967.

- 15 - The Philadelphia Library of American History,

http://www2.hsp.org/collections/manuscripts/e/Earle3260.html#ref2 - 16 - Quote taken from a transcript of the conversation between Gorbachev and Jaruzelski in Moscow on 13 April 1990, translated by Anna Melyakova and kept at the Archive of the Gorbachev Foundation, The National Security Archive at the George Washington University, Washington DC.

- 17 - See the order and the translation in the Jan Jarka story, Vanquish Evil by Doing Good,

https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/jan-jarka/ - 18 - Karta Indeks Represjonowanych,

https://indeksrepresjonowanych.pl/int/wyszukiwanie/94,Wyszukiwanie.html - 19 - Photograph from the Turkiewicz collection.

- 20 - Zawodny, JK, Death in the Forest, The Story of the Katyń Forest Massacre, pages 102 & 103, Macmillan London Ltd, 1962.

- 21 - Ibid, Mackewicz, page 191.

- 22 - Ibid. Vanquish Evil By Doing Good.

- 23 - Ibid Mackewicz, page 22.

- 24 - Remnick, David, Lenin’s Tomb, The Last Days of the Soviet Empire, page 6, Random House Inc, New York, 1993.

- 25 - Ibid, page 5.

- 26 - Ibid, pages 5 & 6.

- 27 - A Shoebox of Ribbons,

https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/a-shoebox-of-ribbons/ - 28 - http://www.labiryntarium.pl/images/stories/x/Ksiega_Cmentarna_Katyn.pdf

- 29 - Ibid, Karta Indeks Represjonowanych.

- 30 - The Gazeta Polonia published the interview with Agnieszka and Przemek Dawidowski in April & May

2016.

http://www.gazetapolonia.nz/en/content/interview-mrs-malwina-zofia-schwieters-part-two - 31 - Ibid.

- 32 - For stories on the Pahiatua Poles, see the War Immigrants page of the website Polish History New

Zealand,

https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/war-immigrants/ - 33 - Rev. Msgr. Zdizislaw Peszkowski, Memoirs of a Prisoner Of War in Kozielsk, pages 64–75, English version published by the Polish Katyń Foundation, Warsaw, Hector Printing and Publishing House, Długołęta,1993.

- 34 - Photograph by Bogusław Nowak.

- 36 - The Soviets forcibly removed more than 900,000 Polish civilians from eastern Poland in four mass train transports, in February, April, and June–July 1940, and in June 1941. Zbigniew used the word “deported,” a term that was generally linked to the Poles’ mass removal from their homes by the Soviets, but one that implies that they were foreigners in their own country, and that they had done something to deserve the treatment. They were not foreigners, and they did not deserve to be forced from their homes.

- 37 - Gurjanow, Aleksander, List of Deportee Transports via Rail 1940–1941, Karta, Warsaw, 1994.

- 38 - Ibid, Anders. For more on the prisons from where few Polish men returned, see the chapter Kolyma Means Death.