Sixty-three Days

The 1944 plan to liberate Warsaw from five years under German oppression was desperate but doable; its reasons were patriotic but backed by military intelligence. Warsaw’s underground Home Army (Armia Krajowa, the AK) anticipated having to keep the occupying Germans at bay for a few days before Poland’s allies arrived in support…

The Home Army could call on about 45,000 soldiers in the Warsaw district, but only 10 percent had weapons. The Germans had about 25,000 well-trained soldiers, supported by artillery, panzer divisions, and the Luftwaffe.

The Warsaw insurgents named the start of their uprising “W-hour,” the W standing for wolność, or freedom, as well as its city. The “few” days extended to 63. The Allies did not arrive. Their ‘help’ turned out to be far too little and too late. The Soviet ‘allies,’ parked their army on the other side of the Vistula and watched as Warsaw burned.

By the time the last shots were fired on 2 October 1944, 18,000 insurgents and 150,000 civilians were dead (on 5 August alone, in the suburb of Wola, the Nazis gunned down about 40,000 residents), 25,000 insurgents had been injured, and the Germans expelled about 500,000 residents from a city in ruins.

The AK accepted the help of boys and girls older than 12. They became invaluable. They delivered letters and orders, acted as guides and look-outs, carried supplies, helped to construct barricades, distributed resistance newspapers, and fought alongside their elders.1

This is the story of one of those children, the daughter and sister of AK fighters, who was among the many who helped medics. She worked at the makeshift hospital established in the basement of the apartment block where she lived, in Warsaw’s New Town, two blocks north of the Old Town, the Stare Miasto.

Her cousin, a member of the Auckland Polish Association, contributed her story, which I have translated as best I could. At the request of her family in Poland, we have kept her identity anonymous.

—Barbara Scrivens

The Warsaw Uprising memorial on plac Krasinskich, taken from the Długa Street side.

I TURNED TWELVE

On June 27 [1944], I turned twelve. I lived with my parents, my brother who was nine years older, and my grandfather, in Warsaw at ul. Franciszkańska 10. From our balcony, about 150 meters on the right you could see Bonifraterska Street, and behind its ghetto wall, the ruins of burnt houses.

This photograph of the burnt-out Jewish ghetto and the wall along Bonifraterska Street, towards Krasiński Square, was taken by Jozef Jerzy Karpiński in 1944. Its angle and the kink in the road suggests he took the image from a window a on Sapieżyńska, and that the kink was where Bonifraterska crosses Franciszkańska.2

My father was an honest and righteous man. I loved and worshiped him. He was gentle and considerate. These qualities did not deprive him of a sense of humour. He also had a wonderful gift for storytelling. When he started telling stories, I could listen with bated breath for hours. I most liked listening to his memories of the Bolshevik war in 1920. My father was 22 years old when he served in the 5th Ulan Regiment. He often volunteered for reconnaissance missions, and took part in numerous skirmishes. He also talked about the charm of the Ulans’ lives, their friendships with their horses, their equestrian gymnastics, and many other interesting things and events. He was a great patriot, ready without hesitation to give his life in defense of his homeland. Almost from creation of the Home Army, he fought in its ranks.

In July [1944], the Home Army was preparing very intensively for an armed uprising. A decision had been made that it would start at 5 o’clock [in the afternoon], just after the curfew began. When the time came, my father and my brother, after serious and cordial good-byes on July 31, left the house at 1.10am. According to their orders, they had to assemble with their unit before the end of curfew.

On 1 August, before the start of the uprising, my mother decided to settle an important matter—to collect money that had been loaned to friends. She had meant to do it two weeks earlier. Now, she considered the matter urgent. At 1.30pm, she left home to catch the tram to Kazimierza Wielkiego Square, where these friends lived. She got there without a problem, but it was impossible to return home. Home Army units waiting in their groups observed the Germans’ preparing to execute hostages and resolved to save them: the insurgent action was started much earlier than planned.

In the afternoon, an old truck pulled up in front of the gate of our house. A woman got out, accompanied by young people wearing white and red armbands. They offloaded huge parcels and began to bring them to the basement annexed to our apartment block. I learnt that the woman was a theatre nurse. She brought surgical tools and dressings. In the basement, she started organising a field hospital. The next transport was to include a surgeon with the rest of the materials. It turned out that much earlier, someone had set out iron beds and mattresses in the basement.

Some of the scouts in the early stages of the uprising, these on Złota Street, with Zgoda Street in the background. Their heroism during the 63 days has been immortalised in the Little Insurgent Monument (Pomnik Małego Powstańca) that stands on Podwale, still guarding the remains of the 16th-century walls of the Stare Miasto.3

_______________

My mother’s absence made me feel free and the mistress of my fate. I knew that now nobody could order me around, or prohibit me from doing anything. Without a moment’s hesitation, I approached the newly arrived nurse, and suggested that she should engage me, and my friend Danka, who was two years older than me, as nurses. The offer was accepted, and we received our white and red [AK] armbands.

The first days of the uprising in our district were relatively peaceful. Somewhere from afar came the sounds of shots. German planes flew past, high above us. There were no injuries [for us to attend]. The nurse taught us how to bandage. We helped her to organise the instruments [that had arrived in the packages] and spread out the blankets on the beds. When people I met saw my armband, I was bursting with pride.

The quiet ended unexpectedly quickly. German planes began to swoop low and dive-bombed the city. Every now and then, the calm was torn apart by the screech of pitcher bombs, so-called cows, or wardrobes, because of the specific sound they made while they were fired, and the damage they did.4

On the street, the Germans exploded a car-bomb. Many of the injured began to be brought into the basement. I looked at the back of a wounded man. There was no skin, no skin, only numerous hollows filled with “jelly” from blood mixed with the earth. My twelve-year-old eyes could not take in the sight. My first reaction was to flee back home.

After a few moments, I came to my senses and cursed myself for such cowardly thoughts. I told myself: “Such a shame! What kind of a medical assistant are you?” I ran back to the basement. I worked as hard as I possibly could. I handed bandages to the nurse, supported the injured while they were having their injuries dressed, carried water, and threw out bloody dressings.

The expected surgeon never reached us. Two veterinarians living in our building were drafted in until the end of the night. Our nurse and direct superior gave Danka and me the job of fetching food for the wounded from the AK command on Freta Avenue.

By the way, I found out that our nurse is from the AK. We got a large military thermos with two handles on the sides and carried it together. Inside was pasta, or kasza [groats] with sauce and preserved meat, and sometimes a slushy soup: barley or pea soup. On top of the thermos lay sliced bread covered with a cloth, in later days, biscuits. After delivering the meals, we helped feed the wounded.

There was a certain regularity in the Germans’ shelling and bombardment of the city. Up to ten o’clock in the morning, it was calm. Afterwards, hell started. We heard the screech of the German lust for our blood, and bombs fell from the sky.

Residents used the morning hours of peace. They left their bunkers and went up to their apartments to prepare hot meals from the supplies that everyone had gathered during the war. My mother was also this far-sighted. Our apartment had flour, cereal, pasta, sugar, a few eggs, onions, and pork lard. I used to cook something hot for myself and my grandfather—some noodles or kasza with bacon, or potato pancakes. Grandfather almost always stayed in the shelter. He was asthmatic and continually felt unwell.

One day, when I was busy with the sick, the Germans started firing earlier than usual—at nine o’clock. People still in their apartments, after hearing the cracks of bullets, automatically ran to the stairwell, and that’s where the shell struck. They all died. Among them was a young married couple. Their two-year-old son survived only because he was in the bunker. From then on, I could not get home, because there were no stairs. Part of our kitchen was also demolished. I was left with one set of clothes, a navy-blue pleated skirt, a white blouse, and a navy-blue jacket. From that day on, I brought additional servings of food for myself and my grandfather from the AK command. After they captured some German warehouses, the insurgents handed out sugar cubes. Both my jacket pockets were stuffed with sugar-cubes.

For a long time, the nights were clear. Darkness was lit by the glow of the burning houses. Our backyards turned into a sizeable cemetery. Alongside the cellars of houses adjoining one another on our side of the street, openings were made in the walls, which made it easier to remove the wounded and killed from various city streets, and helped protect us from sniper bullets.

The situation was getting increasingly harder. The Germans bombed the waterworks. There was no water. I received the order to bring water from as far as Powiśle, almost from the Wisła itself. On my first trip to collect water, I saw a dead woman lying on the street. She was wearing a dress identical to the one my mother wore when she left the house. I experienced shock. Despite my conviction that my mother was alive, I could not forget the sight of that lifeless woman.

Townhouses on Zakrzewski Street, Warsaw. This photograph was taken by AK liaison officer Ewa Faryaszewska, and is part of an exhibition at the Muzeum Warszawy, Centrum Interpretacji Zabytku Stare Miasto (Museum of Warsaw, Old Town Monument Interpretation Center). The reason its caption states that it was taken “before 28 August 1944” is because that was the date of her death.

In the end, the worst of all days came. On the last day of August, we saw German soldiers with unlocked rifles running into the shelter. There were only three Germans, but they were accompanied by many Ukrainians. I felt a painful contraction of my heart and I was overwhelmed with despair, that all we had done was in vain. So much suffering and so much death went to waste.

The Germans threw us out of the basements and drove us through the streets of the city. At dusk, we stopped in front of the church in Wola.5 The Germans separated the men from us, that is, the women, children and the elderly, and locked us in the church. We heard the children’s cries and the laments of women who were convinced that their men would be taken to work in Germany, and that the Germans would bomb the church with us inside.

Within the tumult of the Warsaw Uprising, the actions of the Germans varied. It is not clear

why some of the staff and inmates at the many makeshift hospitals were spared, yet others not.

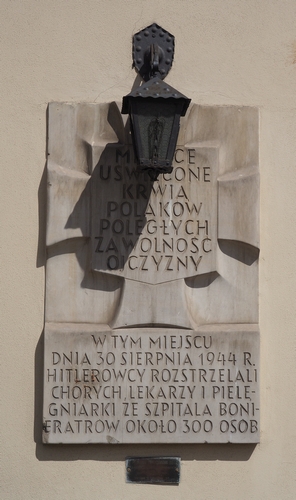

This plaque, outside the Zakon Szpitalny Św. Jana Bożego Bonifratrzy (Hospital Order of St. John of God) on Bonifraterska

Street, remembers 300 doctors, nurses and the injured shot by German soldiers shot on 30 August 1944.

Defeated Varsovians marched out of their ruined city along Grójecka Street.6

I spent the night lying huddled on a stone platform in front of an image of one of the saints. In the morning the large church gate opened, and a man accompanied by a German soldier brought a bucket of water and a few mugs. Thirsty women began to wrestle for the water. The German shouted something, and the man calmed the crowd, assuring them that in a moment, he would bring more water. Indeed he did, until everyone’s thirst has been satisfied. Then we were told to go on.

We reached the camp in Pruszków.7 In front of one of the many barracks, they distributed swede soup to us, in tin plates. It had been made in a large cauldron. Once we finished the meal, a uniformed German with an interpreter sorted us. Girls older than 14 and women without small children were ordered to enter the barrack. The rest, including me and my grandfather, were loaded into trucks and taken to a village behind Piotrków Trybunalski. Waiting for us was a village administrator who deployed us among the local farmers.

Along with my grandfather, I connected with good and wealthy people. The house was spacious and clean. Everywhere there was an exemplary order. The owners were very warm and welcomed us as if we were expected guests. We slept in clean and starched bedding. They did not skimp on our food. We had fresh milk, butter and cream, cheese, fragrant country bread. The dinners were delicious and plentiful—with meat.

After two weeks, people from the next transport from Warsaw took our places, and we were again loaded onto trucks and driven even farther to a village of wooden dwellings in the Końskie county. The nearest railway station was 30 kilometres away.

This time we came to young and very poor people. Their hut was cramped. In the kitchen, instead of a proper floor, it was earth. The whole hut was black from dirt. We slept on straw mattresses under dirty horse-blankets. Our hosts cooked the same soup every day—sour rye soup, which we ate three times a day. To go with it, we had a slice of bread and unsweetened black coffee to drink.

Early in the morning, the hosts went out to work in the field for long hours. Before leaving, the hostess spread a rug in the middle of the kitchen and sat an eight-month-old baby on it, for me to look after. For the baby, she left kasza cooked in milk that she put in an old vodka bottle, and a dummy. The fire under the hob was lit. She must have added some of the chopped wood, piled at the kitchen door, and looked after the fire as it cooked the soup in the large iron pot. I swept the kitchen floor with a wooden broom, and sprinkled the beaten ground with water from the well in front of the house. My grandfather coughed a lot. He still suffered from shortness of breath, and preferred to sit outside, in front of the threshold.

Very quickly, I was covered with enormous lice. There were thousands. Not only in my hair, but also throughout my clothes. I tried to fight them. I poured water into a pot, put it on the hot stove, took off my blouse and threw it in the boiling water. Then I wore the same blouse. The next day I put on my blouse and jacket, and cooked my under-blouse. Every two or three days I also cooked my only panties and dried them in front of the hot stove before our hosts returned. Unfortunately, I could not boil the skirt and jacket.

When the front began approaching our village, the German authorities issued an order for one person from each dwelling to report every day with a shovel, to dig anti-tank pits. The young couple sent me to this job. I got a slice of black bread and a bottle of black coffee, a shovel in my hand, and left the hut.

I was completely unused to physical work. The dug holes were deep. When I tried to shovel out the soil, a large part of it fell on my head. In the evening, all my muscles ached, and I had chills. I lasted only for two days. The next day after work, I did not return to the hut, but just sat on a piece of felled tree in the square in front of the church and began to cry. A priest saw me. He came up to me and asked, “Why, child, do you cry?” When I told him, he took my hand and led be back to the hut. He talked to the hosts in private. From then on, they did not send again me to dig trenches, but I returned to my previous activities.

_______________

My mother took her debt, but our friends died in the bombing. From the insurgents, she learnt that the Germans had already won the Old Town. At the beginning of September, the Germans announced through loudspeakers that residents could leave Warsaw with a white flag, assuring them that nothing would happen to them. In the hope that I was still alive, my mother decided to leave the city on September 7th. While she was marching among other people leaving Warsaw, one of the German soldiers standing guard noticed that she was walking in just a dress and without any luggage, and threw her a small, rolled-up rug. Later, on increasingly colder days, and especially nights, she covered herself with it.

In a column like this, a single woman with nothing in her arms could so easily have slipped by without a guard noticing, or caring.8

The money she took with her was to be a real treasure. My mother, like everyone leaving Warsaw, in the first stage of the march, reached the camp in Pruszków. A man came up to her and started a conversation. She did not recognize him. He reminded her that he had been in love with her 20 years ago and had even proposed to her, but she had not accepted his proposal. When he later moved to a street neighbouring ours, he saw me and my brother, and knew we were her children.

He informed my mother that on the day before the Germans entered [our neighbourhood], he saw me whole and healthy. Mama paid a warder to take her during the night to another barrack, where the wounded and sick were staying. In the morning those who could not stand were transported to the nearest hospitals, and those able to move unassisted could leave in any direction. When Mama was released from the camp in Pruszków in this way, she was able to start her pilgrimage—searching for me.

She wandered from village to village. Most often, on foot, sometimes a few kilometers on a cart driving along the road. To everyone she met in the villages, she always asked the same question: “Is there a 12-year-old girl here, a brown-haired with pigtails?” After hearing negative answers, she continued her journey.

She spent the nights in rural households, usually for free, and sometimes for a few pennies. One day, she got to the house that I had previously stayed. She assured herself that I was definitely alive. That discovery gave her strength. After spending the night, her hostess gave her food for the road, and she carried on. Many more nights and days passed before she received an affirmative answer to her question and was pointed to the home where I was staying.

I had just finished wiping up after the baby, and had taken up the broomstick to sweep, when I heard a knock at the kitchen door. I did not manage to answer, because suddenly the door opened and there stood my mother. I threw myself at her neck. It was the happiest day.

Immediately after the hosts returned, my mother thanked them for taking me in, and we went to the neighbouring village. Grandfather would not have endured such a long walk, so he had to stay with the hosts for the time being. We managed to reach the latest hut my mother had been staying in, just before night. I had a hot bath in a huge bucket. I got some old clothes of the hostess’s to wear, and mine—lice-infested—were burnt. For two days my mother cleaned my head. On the third day after breakfast, we received some clothes and provisions for the road. We said our goodbyes and headed back towards Warsaw.

Snow was already lying on the fields. When we encountered an anti-tank unit, we lay on the snow and used our hands to move gently, so as not to sink deeply. Then we walked on. After several hours’ walking, we arrived at the narrow-gauge railway station. Many people were waiting for the train. When it arrived, my mother lifted me up and helped me clamber onto the crowded train roof. She handed me the bundle from our last hostess, and told me to wait for her at the next stop. She arrived very tired. We travelled 40 kilometers on that day.

After reaching a village before Milanówek, my mother rented a small room with a narrow bed in which we slept together. It was warm and clean there. We did not lack food.

When news got to us that Soviet troops were already in Warsaw, we started out on the road again. Once we reached the Wisła, we saw that the two pontoon bridges were exclusively for military use. With our hearts in our mouths, we crossed the frozen river on foot. We stayed with close friends in Praga. Then my mother experienced the greatest drama of her life. She learnt that her son was dead. An hour before the capitulation was signed, my brother was shot in the groin. He died in a hospital in Tworki [Pruszków], where Germans transported wounded insurgents. He rests in the hospital cemetery. On his tombstone, in addition to the first and last name, there are the words: “AK soldier” and the pseudonym “Igor.”

After the uprising, my father ended up in the POW camp in Altengrabow [in Germany, Stalag XI-A, also known as Stalag 341]. After the Allies released the camp, he made his way through the formations of various troops to return to his family as soon as possible. At first, the military authorities did not let Poles through. My father, however, knew the Russian language not badly. He acted like a Russian. Thanks to this, he was let go and he managed to return quickly to Poland. He found us in Praga with friends.

After the release of further Polish lands, when some trains began to run, grandfather returned. Gradually, the situation began to normalise a little. We were allocated one room with the use of a kitchen [elsewhere]. My father returned to work, and I returned to my interrupted schooling.

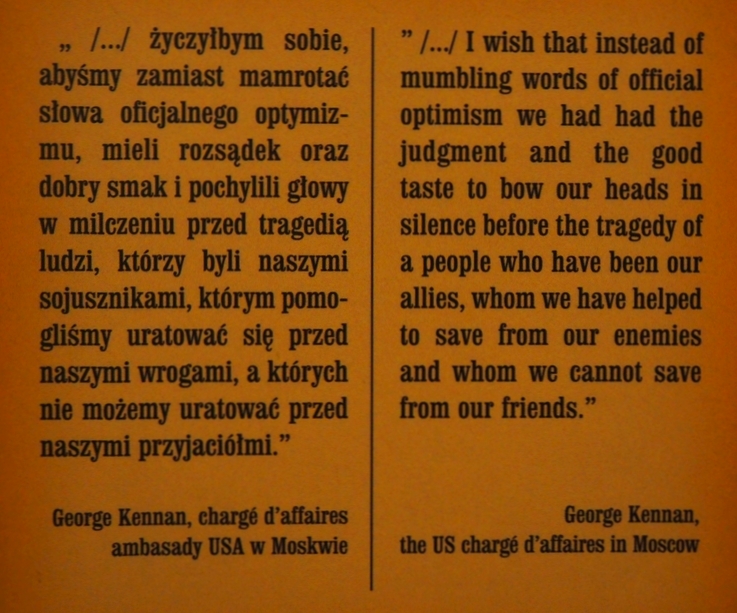

In an 8,000-word telegram dated 22 February 1946, George Kennan, Charge d'Affaires at the United States Embassy in Moscow to the Secretary of State, summarised the perfidy of Poland’s alleged WW2 allies. This quote is part of the exhibition at the Warsaw Uprising Museum in Warsaw.

© October 2021.

FOOTNOTE: The writer became a medical doctor, specialising in paediatrics. We will pass on the message of anyone wanting to contact the contributor.

ENDNOTES:

- 1 - These numbers and details come from exhibits at the Warsaw Uprising Museum in Grzybowska Street, in Wola, Warsaw.

- 2 - Thanks to Wiki Commons. The photograph was published by Antoni Przygoński in 1980, Powstanie

Warszawskie w sierpniu 1944r.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Warsaw_Uprising_-_Getto_at_Bonifraterska_Street_by_Karpinski_3.jpg - 3 - This photograph by Marian Grabski is part of the exhibition at the Warsaw Rising Museum.

- 4 - Each of these bombs included a cluster of four heavy-grade demolition rockets attached to two napalm

rockets. The buildings hit by them collapsed instantly and incinerated anyone inside or nearby. From the website, Warsaw

Insurgents Cemetery in Wola.

http://www.sppw1944.org/index.html?http://www.sppw1944.org/pamiec/cpw_eng.html - 5 - The Chronicles of Terror website names St Adalbert’s Church at 76 Wolska Street as the one

through which about 90,000 Varsovians passed on their way to the Pruszków Dulag 121 transit camp.

https://www.zapisyterroru.pl/dlibra/context?id=context1 - 6 - This photograph is part of the exhibition at the Warsaw Uprising Museum. The photographer is unknown.

- 7 - The Germans created the Pruszków “transit” camp during the uprising. About 650,000 Varsovians

passed through. German officers decided which prisoners were fit to work as labourers in Germany. They sent about 55,000 to

concentration camps, including people of different social classes and ages, and about 150,000 to Germany as forced

labour.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pruszk%C3%B3w - 8 - Ibid, Warsaw Uprising Museum.