Witold Jan (Victor) Pleciak

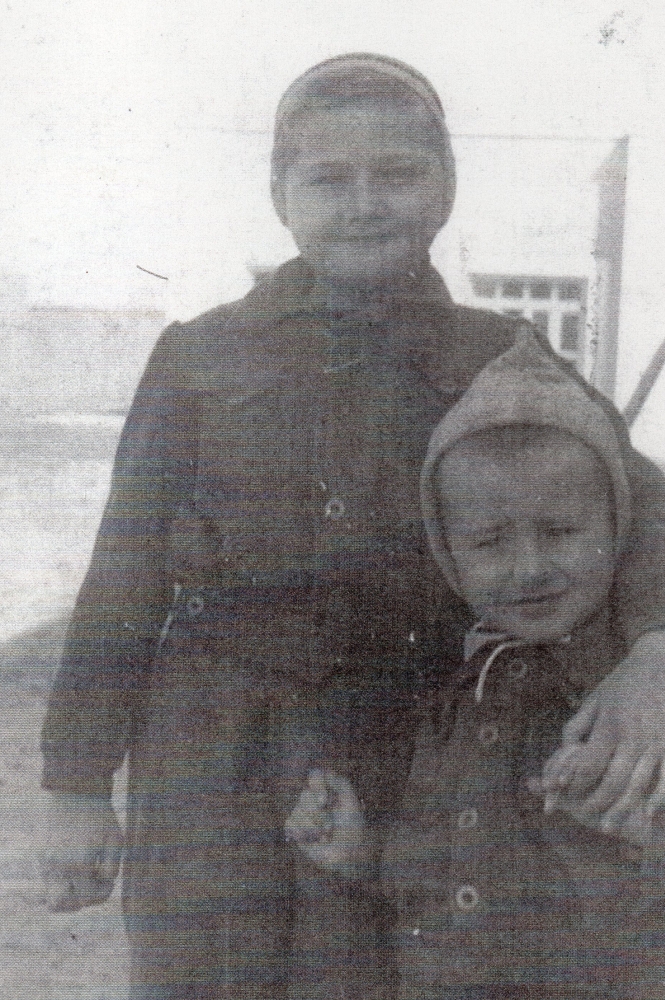

The heart of this story revolves around this faded and out of focus photograph.

Zofia Pleciak holds a protective hand around her brother’s as she looks towards the camera, but her other hand is tense. One can only wonder what effort that smile took as she cradled “Wituś,” six years her junior.

The two were somewhere in the USSR in 1942. The building in the background may have been the one used by the Polish orphanage that took them in after their parents died in Uzbekistan. Ten-year-old Zofia was old enough to remember that their elder brother and two sisters had left with the Polish army, but four-year-old Victor was not.

I first met Victor and his family at the Dom Polski in Auckland in March 2018 when he received his Siberian Cross (Krzyż Zesłańców Sybiru), an acknowledgement from the Polish government of the hardship he suffered under the Soviet regime in the USSR during 1940–1943.

Victor’s wife of more than 50 years, Elaine, absorbed many of his stories and was a perfect prompt during our subsequent interviews. Although Victor was barely two when the Soviets forcibly deported his family to Siberia, his sisters Zofia and Jadwiga helped flesh out the personal family memories.

Other background aspects for this story include those from the websites of Poles who have taken the trouble to document families in pre-war Poland. Links to those sites and others appear in the endnotes.

I thank Victor and Elaine for their gracious hospitality and time, and the entire village of Hallerowo, Wołyń, for being part of the process.

—Barbara Scrivens

AWAKENING MEMORIES

by Barbara Scrivens

Victor Pleciak could never sharpen the image of a man standing in a field with a haymaking fork.

“The fork was very large, two or three-pronged. There is something even now when I think about it, and in quiet moments. I don’t know if it is true or not but it must have been my dad.”

Victor is candid about not remembering his infant years in Poland and has his sister Zofia to thank for awakening his single vague recollection of their father. Victor became aware of the image as she spoke to him years later about the family farm in Hallerowo, in the then Wołyń province of eastern Poland.

In every photograph Victor has of his father, Wojciech, he is dressed in military uniform. It is not clear whether this one was taken at the farm in Hallerowo, during the Polish-Soviet War, or while he was serving as a reservist defending eastern Poland from Bolshevik raids.

Victor’s time as a child captive of the Soviet NKVD during World War 2 would have remained a blur without Zofia and their eldest sister, Jadwiga, who wrote several depositions and memoirs about their Polish home, how they were forced to leave it, and what happened afterwards.1

When Soviet troops invaded eastern Poland on 17 September 1939, 53 Polish families lived in Hallerowo or close to its boundaries.2 By the time German troops headed the other way in June 1941, few of those families remained.

In 1939, the occupying Soviets appointed Ukrainian committees to manage the Polish population. That the Ukrainians embraced the Soviets so quickly surprised their Polish neighbours, who underestimated their previously hidden resentment.

One could put the blame on the 1918 Treaty of Versailles. It had declared a revived Polish republic—after 146 years of Russian, Prussian and Austro-Hungarian partitioning and rule—but left the boundary between this new Polish nation and the Ukrainian SSR dangling (and did not ratify Poland’s western boundary with Germany either). Tensions between the Poles and the Bolsheviks led to the 1919–1920 Polish-Soviet War, which the Poles won.3

Ukrainians caught on the Polish side of the new border, ratified by the Treaty of Riga in March 1922, had already been living among Poles in what had previously been part of Russian-partitioned Poland. They seemed to integrate well with the new Polish military settlers who moved east after the war, like Victor’s parents, Wojciech and Maria (née Fidelis) Pleciak.

Cartographers at the Wojskowy Instytut Geograficzny, Warszawa (Military Geographical Institute in Warsaw) first drew Hallerowo in 1924.4 Situated west of Szubków on the meandering Horyń river, it was among scores of osady (military settlements), set up by the new Polish government to improve land previously abandoned and impoverished through decades under Russian partitioning and then trampled and littered with the detritus of war.

The osady solved two issues for the new Polish government: how to reward and occupy the thousands of young men who had volunteered to fight for their new Poland and how to contain the still marauding Bolsheviks. Men who had fought in the Polish-Soviet War had the opportunity to take on government loans to buy land in eastern Poland. Those same men, militarily trained, were on hand to protect that land and the new border.

Wojciech Pleciak was born in Łódź and Maria Fidelis in Kalisz. It is not clear exactly when they moved to Hallerowo but Jadwiga, their first child, arrived on 3 November 1923, before they had built a house on the property. She described their shelter as a “cabin.”

Maria Fidelis Pleciak, right, when she was about 18. Family believes the other young woman may have been Wojciech's sister.

Wojciech Pleciak. His cap badge and lack of other insignia suggests he had recently volunteered to fight for his revived homeland. His conduct during the subsequent 1919–1920 Polish-Soviet War later earned him the Krzyż Walecznych (the Polish Cross of Valour).

This map, showing Hallerowo and neighbouring osady, and Tuczyn, is part of the collection originally drawn for the Wojskowy Instytut Geograficzny, Warszawa (Military Geographical Institute in Warsaw). It forms part of the archives digitised by Mapywig.5

Neighbour helped neighbour in Hallerowo. Fellow settlers worked alongside Wojciech as he built that first shelter, where Jerzy joined the family in 1925. Barbara, Zofia and Victor (christened Witold Jan) were born in the new house in 1928, 1932 and 1937.6

On his 14 hectares, Wojciech grew sugarbeet and tobacco under government contract, and also wheat, rye, oats, barley, buckwheat, millet, rape for oil, and potatoes. He kept horses and Maria tended the garden and vegetables. Chickens laid their eggs, cows gave their milk and one of the pigs was always destined for the Christmas or Easter table.

Like in so many osady, the settlers built a school and later their own church.

Jadwiga loved the communal summer picnics at a “strip of meadows” the settlers bought along the Horyń river.

“Usually for Pentecost we would go there with the whole family with bread, meats, and cold drinks. We would spend the whole day outdoors. Those were the most beautiful days of my life and I still dream about them.”

_______________

All changed when Hitler invaded Poland from the west on 1 September 1939 and Stalin sent his troops in from the east 16 days later.

Jadwiga: “In October [1939] the Ukrainians announced that we had to leave our homes and land. They allowed the settler families to bring only what they could fit in a cart. We were allowed to take one cow and a horse with a cart, and kitchen equipment, clothes, bedding and food.”

“My father rented a few little rooms in Tuczyn… There were five of us children… also Father’s sister, Zofia, who escaped from Warsaw to our settlement in the first days of the war with her daughter Halina and son Adaś.

“We were very crowded in the two little rooms with a little kitchenette. We didn’t lose our spirit, though, and we hoped everything would be over soon.

“In January [1940] a Soviet representative in Tuczyn announced to us that Aunt Zosia, Halina and Adaś would be taken away to a safe place…

“10 February 1940. Early in the morning, a Soviet soldier banged his rifle on the door with the typical order: ‘Sobirajsia z wieszczami!’” (In Polish, “Zabierajcie się z rzeczami” or “Get ready to go with your things.”)

Jadwiga recalled large snowflakes falling as a waiting sleigh took her family to the Równe railway station and the Soviet soldiers loaded them onto cattle wagons “70 people per car, whole families were sitting on bunk beds by the walls.”

Six days later the train rolled into Szeptówka, the first large railway hub on the USSR side of the border. The prisoners received coal for the stove, and water.

Jadwiga: “We started moving again, passing fields and forests covered with snow, cities, towns and villages, all covered with snow. It was very cold… We stopped from time to time at bigger stations, where we could get kipiatok [boiled water] or some soup and coal for the stove. We went on and on.

“Sometimes in the middle of nowhere we would be allowed to leave the cars to go to the bathroom next to the train and stretch our legs. Our bathroom in the train was a hole in the floor, covered by some cloth—very awkward and embarrassing.”

Jadwiga remembered passing Orzeł, Moscow, Oriechowo, Wladimir, Gorki and Kirow before reaching “the goal of our forced journey,” Kotłas, where the Poles were herded into a classroom.

“That crowd of people! …Whoever found a place to lie down or sit was lucky. I remember half the night I had to stand because there was no room. Outside it was bitter frost.”

Their “forced journey” continued the following day with another sleigh ride, this time along the frozen Dwina river to Priewodino (Privodino) and another overnight stay. On 1 March 1940, a narrow-gauge train took them through the forest to Kotlowalsk7 where overcrowding grew to such a level that many slept on the floor.

Jadwiga: “Men and youth were taken to work cutting down the trees… It was a time of bitter frost and snow. The work was very hard and without proper nutrition, it was exhausting.”

After three weeks they were moved to what was supposed to be their final destination—the NKVD forced-labour facility of Monastyriok. There, families had their own spaces within the barracks, and shared the iron stove that stood in the middle of the room. Jadwiga worked with her father in the lumber mill, cutting wood into specified lengths and removing the bark. Elsewhere, 15-year-old Jerzy chopped wood for heating the school in neighbouring Priewodino. At first, the three youngest siblings remained with their mother in the barrack.

_______________

The website strony o wolyniu8 lists the Hallerowo residents’ names in order of where they lived, starting from the Szubków side, west-south-west towards Równe: Bronowicki, Każmierczak, Kwinta, Bekta, Grzelczak, Przecławski, Budzyń, Lelek, Cierniak, Pleciak, Cisałowicz, Lupicki, Śmigiera/Śmigera, Miodoński, Kąkol/Konkol, Kurcz, Sułomirski/Sulmiński, Pużański, Manguszewski, Rybakowski, Doleżan, Fiołek/Fijołek, Krajewski, Oleś, Wojewódzki, Kołacz, Mastaj, Makarewicz, Polewski, Straszyńkski, Taborek, Wiącek/Wiencek, Wolny, Chmiel, Dąbrowski, Słomka, Lupa, Łuczyński, Zawadzki, Pietrek, Stasiewicz, Kaczkowski, Szarczyński, Żygadło, Stepaniuk, Marchewa, Szczygłowski, Gwóźdź, Bogatek, Kuźmiński, Szauer, Mierzwa and Węgłowski.

According to their records, the NKVD sent 14 of the families—92 people—to Monastyriok. Besides the Pleciaks, they included the families of Budzyń, Cisałowicz, Oleś, Kołacz, Makarewicz, Słomka, Taborek, Zawadzki, Pietrek, Stasiewicz, Marchewa, Mierzwa and Węgłowski. The NKVD sent six families to Komarticha: Bronowicki, Doleżan, Polewski, Szczygłowski, Gwóźdź and Bogatek, and five to Jentoła: Śmigiera/Śmigera, Kurcz, Rybakowski, Wolny and Kaczkowski. All three destinations were near Kotłas, one of the Archiangielsk region’s largest railway hubs.

It is not clear what happened to the rest. Some were sent singly to other forced-labour facilities. By the time the NKVD had started to round up the families in February 1940, former soldiers such as Stefan Miodoński had already slipped away to join the Polish underground, the Narodowych Sił Zbrojnych (NSZ). As Major “Sokół” (Falcon) Miodoński, he commanded the Okręg XII Podlasie (XII Podlasie District) for the NSZ from the spring of 1943 to the beginning of 1944.9 The NKVD sent his wife and children to Kazakhstan. The UB (Urząd Bezpieczeństwa, or Security Police) arrested him in October 1945 and released him “exhausted and close to death” in April 1951. The Falcon died that June.10

Hallerowo parish priest Jan Kąkol signed Victor’s birth certificate, a document he finally received in 2011. (Until then he had lived with a birthdate allocated to him, 26 December 1937. His actual one was only a week out, 2 January 1938.)

Jan Kąkol was arrested in 1940 and imprisoned in Gross-Rosen and Dachau until 1946. The UB arrested him again in 1950 at the Boguszów parish in Lower Silesia and imprisoned him for another 10 months. He died in 1964, in Gołdapia.11

It is not clear what happened to Hallerowo’s mayor, Ignacy Szarczyński, or Stanisław Chmiel, its “alderman.”

_______________

In 1940 Monastyriok, as the seasons changed, so did the jobs allocated to the four oldest Pleciaks. Once the Dwina river thawed, Jadwiga and her mother carried river water to the bania (baths), “very hard work.” At another job “under a roof and by a belt,” Jadwiga recalled how the labourers had to “hurry a lot.” In autumn, the family foraged for berries and mushrooms.

“The locals said they didn’t remember the last time there were such good crops. We dried the mushrooms to use in winter, and we used the berries… to make juice and jam with a little sugar, which we saved whenever it was allocated. That kept us alive.

“I would go with my mother to the nearby villages with bundles of clothing to exchange for sugar, pork fat or potatoes. Then the winter came and everyone suffered poverty.

“Very few articles of food were being delivered to the cooperative and, when there was something, it was snatched very quickly. The last kopeks were spent to make some supplies for winter.”

In a deposition he wrote in 1942, my grandfather Stanisław Nieścior noted that at nearby Tiesowaja, where the Krajewski family from Hallerowo were sent, the inmates knew nothing about what was happening in Poland. The Soviet guards “repeated reminded” my grandfather to forget about Poland and that “we were here forever.”12

Those predictions changed when Hitler’s troops crossed the border dividing German- and Soviet-occupied Poland on 22 June 1941. As the German divisions of his former Axis partner drove towards Moscow, Stalin started negotiating with the Allies and realised he could slow the invaders with the expendable and available Polish men he had incarcerated in the USSR. He created an ‘amnesty’13 for the Poles.

News of the ‘amnesty’ for the Polish prisoners in Monastyriok arrived with an incorrect proviso that it was “not for everyone all at once.” Some of the Poles started to apply for transfer back to Kotłas, the first step in reaching the Polish army that they heard was gathering in southern Russia. They had no idea of the political machinations but ached to fight for a free Poland. They well-remembered a partitioned Poland and did not want it to disappear again into its pre-1918 status.

Even with the general news of an ‘amnesty,’ travelling within the USSR without relevant documents invited re-arrest by Soviet authorities. The NKVD commandants of the forced-labour facilities had the authority to issue travel documents. Some performed their duties quicker than others.

In Monastyriok, jobs dwindled for the remaining families, who sunk into increasing malnutrition and poverty. Wojciech became so ill, he was taken to hospital, “very weak… overworked… his body had lost its immunity.”

Wojciech may have realised that travel documents would not be forthcoming from the Monastyriok NKVD commander because he started to plan the family’s escape without them.

By December 1941, the Pleciak’s provisions in Monastyriok had run out. Again without jobs, Jadwiga and Jerzy made their own plans to escape with friends Janina Oleś from Hallerowo and Krysia Gałkowska.

They walked along the main road to Kotłas, and accepted a ride on a truck carrying Russian workers. A Polish corporal found the teenagers accommodation while they waited for an available train but they soon realised they did not have enough food for the long trip south. Jerzy and Janina returned to Monastyriok for “dried bread and onions” but only Jerzy returned: Janina had been “kept” at the facility.

Jadwiga, Jerzy and Krysia left Kotłas on the same kind of train as the one on which they arrived. As before, about 70 people crammed into each wagon, still configured in the same way as the wagons in which they had arrived nearly two years earlier—lined with wooden slats. The difference was that, apart from two other women travelling with their husbands, the other passengers were former or future soldiers. The women befriended Jadwiga and Krysia.

_______________

Jadwiga and Jerzy separated when Jerzy contracted typhoid and was hospitalised. He later recounted how a Soviet officer in then Stalinabad (now Dushanbe), Tajikistan, tried to talk him into joining the Polish troops that the Soviets were gathering and moving towards Poland. Jerzy slipped away and instead made his way to the genuine Polish army camp in Guzar, Uzbekistan. (For more details about the formation of the Polish army on Russian soil, see military timeline, 1941)

The rest of the Pleciaks were already in Guzar. Wojciech had joined the Polish army and worked in an office. Jerzy found his mother, Barbara, Zofia and Victor in the nearby civilian camp.

Elsewhere, Jadwiga had her share of illnesses and hospital stays but was evacuated out of the USSR by the Polish army on one of the first ships from Krasnovodsk (now Turkmenbashi), Turkmenistan, to Pahlevi (now Bandar-e Anzali) in Persia (now Iran).14 She joined the PSK (Pomocnicza Służba Kobiet, the Women’s Auxillary Service) and lived in the Teheran military camp.

Jadwiga (Dziunia) Pleciak Pawlowicz.

“I was still waiting and asking if anyone knew when my family would arrive… I saved my rations and had chocolates for my siblings and mother and cigarettes for my father…

“I received news that my father had died during an epidemic of dysentery and soon after, my mother died of typhoid in Guzar. My youngest siblings, Zosia, 10, and Wituś, 4, were taken to an orphanage, and Basia, 14, joined the Junaczki15 and came to Iran. Here she got sick with the pellagra and soon died in the hospital near Teheran.”

Barbara Pleciak’s headstone at the Polish cemetery in Tehran. According to the Polish Embassy there, she lies among 2806 Polish graves in Iran. All 650 of the military deaths were through “weakness and epidemic diseases.”16

The Polish cemetery in Tehran. This photograph was taken in 2007 by Robert Wielgórski.17

_______________

Wojciech Pleciak’s death in Guzar lit the fuse to Victor’s clear memories.

“I remember a man lying dead in a room. It must have been my father because my brother and sisters were at his feet. I was four and running around. I didn’t know what was going on.

“I can still remember that image. Everyone was kneeling at the bed. There were two women. I was on the floor playing about, being naughty. It must have been my sister, she gave me a clip on the ear and dragged me towards the group, so I had to sit still.”

Wojciech Pleciak was buried at the Guzar military cemetery.

It is unclear exactly where the Polish orphanage that took in Zofia and Victor was located in southern USSR but the inscription at the back of this photograph of the two of them is the reason Victor knows exactly when they left the USSR—8 March 1943—and through which town—Mashhad.

That place name written next to the date suggests the youngest Pleciaks travelled over the mountainous border between then-Turkmen SSR and then-Persia. The orphans would not have been aware that time for them to leave the USSR had been running out.

The Polish army had already evacuated nearly 70,000 Polish soldiers and civilians across the Caspian Sea in the same transports as Jadwiga, Jerzy and Barbara. Stalin stopped those sea crossings in September 1942. The Polish children in orphanages still behind the USSR border were in real danger of remaining in Soviet hands.

_______________

Perhaps it was age, perhaps it was a feeling of safety, but Victor’s first vivid memories came from his time in Persia. He and Zosia lived in different sections of the same compound. Victor remembers about 200 boys from his age to teenagers “packed in like sardines.”

Because of the strict separation between older and younger children, and the boys and the girls, Victor barely saw Zofia in Isfahan.

“I knew she was there—I was told that—but they separated us for some reason. The little ones, it wouldn’t have mattered, but we were always separated.

“I met the Shah. He gave a party for all of us young ones. There were sweets and lollies… The place was so opulent. Having gone through all that drama, trouble and dirt, to suddenly see something so clean and tidy and everything bright new, it was like heaven.

“We couldn’t believe our eyes. We didn’t know what to do at first. We were in a group and just looking around, ‘What is this place?’ It all goes through your mind… Then, it was just us kids running around and sitting on the floor, chomping on these goodies… chomping on the lollies and halva, I think, and chocolatey things I can’t describe. We loved it.

“Whatever they gave us, we shoved it in our mouths because it was sweet. It was so incredible to eat all these things after the hardship we went through.

“Yet the Persian people were so poor. They used to drill holes in the walls around the compound—the walls were mud and about six or seven feet high.18 We gave them some of our bread and they gave us firecrackers, shaped like golf balls. You didn’t light them. You threw them on the ground as hard as you could and they exploded with a huge bang. We loved it. We soon learnt that we should take a bit more bread than we needed at meals… not so much fruit because there wasn’t any fruit around.

“The holes weren’t nice, neat holes. They were rough, jagged like a fist through a wall, made with sticks and a hammer. The older kids knew the drill because there were quite a few holes around and they came in twos. One was to give the bread, the other hole to get the firecracker.

“One time I remember distinctly… We were handing out this bread to the Persians through the holes and I didn’t want to let go because I was quite hungry, so this Persian grabbed my arm. He tried to pull me through the hole.

“I was so frightened, I started to yell and cry and the kids at the back and one of the adults pulled me back. That Persian was annoyed. I had grabbed his firecracker but I wouldn’t give him the bread. I didn’t want to. I was hungry myself.”

Victor remembers Jerzy helping make the holes in the compound walls. Already 18 in 1943, Jerzy could have been visiting before he left for military training.

“At the time I didn’t know what ‘brother’ meant, or ‘sister,’ but he was there. He went to the Polish army and fought at Monte Cassino.” (For more information on the Polish effort during the final battles, see military timeline, 1944 and scroll to the dates in May.)

Victor’s closest relationships became those he made with the boys he lived with.

“They kept us together. We went to Persia together and we went to New Zealand together. I don’t remember much of the ship that took us to India, the sontay, but I do remember the general randall. That was wonderful.

“It was an American liberty ship bringing New Zealand men home. They treated us like we were angels.”

Angels?

“Like little gods, if you like. We could run around all over the ship…I really enjoyed that…but they were strict with mealtimes and going to bed.

“They had an American crew and American food like hamburgers. We slept in bunks, three on top of one another, and I was on the top bunk. Boys underneath would hit me when I climbed over them. I would reciprocate. I was half-way up the ladder one time, when the boy underneath pulled me down and I got annoyed, so I stomped on his head, or face. He didn’t like that and we were about to fight… I think one of the adults intervened and separated us. He was bigger than me so I wouldn’t have picked a fight.”

_______________

Pahiatua became home for Victor, the other Polish children and their caregivers. (See the introductory stories in pahiatua refuge) As part of the youngest group, he slotted easily into the strict camp routine, a must with 733 children of all ages.

A New Zealand soldier carries six-year-old Victor to one of the dining rooms on the day the children arrived in Pahiatua on 1 November 1944.19

Children at the Pahiatua Camp soon became used to photographers. Here Victor (third from right) and some of the other youngest boys focus on the photographer instead of New Zealand Camp Commandant Major P Foxley’s demonstration of a ‘disappearing’ sixpence. The photographer was probably John Pascoe.20 The boys from left are Bronisław Pietkiewicz, Edward Wała, Franciszek Szpetnar, Stanisław Banaś, Eugeniusz Sarnecki, Michał Guc, Bronisław Węgrzyn, Ryszard Gołębiewski, Kazimierz Dudek, Ryszard Tymicki, Witold (Victor) Pleciak, Bronisław Witaszek, and Jan Lepionka.

Miss Hay, the English teacher, made a huge impression on Victor.

“School was all in Polish in the beginning. It wasn’t until later we got New Zealand teachers.

“They had to teach us English. It wasn’t school as such, it was more trying to get us to assimilate into the New Zealand way of life but we had to learn the language.

“Miss Hay would show us a picture of a horse. She would say ‘horse’ and we’d all say ‘horse.’ Then she’d show us a picture of a house, and say ‘house’ and we repeated, ‘house.’ That’s how it started, trying to relate the name to the picture.”

You Are My Sunshine and Waltzing Matilda joined the boys’ repertoire of Polish songs when an Australian nun taught Victor’s class. She regaled the boys with tales of her homeland and became another special teacher.

“I could sing You Are My Sunshine right now.”

Victor is the boy looking away in the middle of this photograph, which has appeared often in stories about the Pahiatua children and is the front-cover image to the book new zealand’s first refugees: pahiatua’s polish children. The captions usually tell of the fun the children had on the see-saws that the New Zealand soldiers made for the children. Victor knew why the dark-haired girl next to him was so serious: they were squabbling after she had tried to push him off his perch. They chuckled about the incident when they met years later at one of the reunions.22

As well as English, in high school Victor discovered Latin, French and German. The language-heavy education worked well for him.

Elaine: “In all the time I’ve known him, he’s only ever made one spelling mistake. I used to say to the people I worked with, ‘My husband, English is his second language; I’ve only known him to make one spelling mistake. Now, that’s one spelling mistake in 54 years…’”

Victor: “In Pahiatua I became cognisant of my surroundings, names of other kids, what we were doing… the Sunday Masses in the great big hall in the camp. Everyone was there. Little kids in front—sitting on the floor usually because there weren’t enough seats—the other kids at the back and the adults standing around the walls. We boys had to behave and we did behave, because it was instilled in us that the church is sacrosanct and we had to respect that, which we did. It wasn’t until after Mass that we’d go outside and stump each other again…”

Elaine: “My father’s friend, Gordon Hogg, was the policeman for Pahiatua and often went to the camp… You had 800 new people arrive in the area23 and know they are Polish, something different, but not too much else about them, so he would keep an eye on them, saw to it that they were all right.

“He said those children were always so well behaved, the best he had ever seen.”

Victor: “We had to be. Discipline was hard.”

_______________

From the end of 1946, the British government agreed to resettle Polish soldiers and the teenagers in Polish cadet schools still stranded in northern Europe, Italy and the Middle East. Despite vehement urgings by British MPs for those in the Polish military to return to Poland, the majority refused to countenance returning to a homeland under Soviet control. They had survived Soviet forced-labour facilities and had no desire to repeat the experience. In any case, thanks to thanks to a deal brokered by Churchill and Roosevelt with Stalin at the 1943 Tehran Conference, they had lost their farms and homes in eastern Poland to Moscow. (For more, read seeing stalin.)

The Polish soldiers lived at first in resettlement camps throughout England and Scotland. The Red Cross helped families reunite and Polish fathers started to find their children in New Zealand.

“I recall it distinctly. We were in our dormitory, in bed in our pyjamas. Men came in, obviously fathers looking for their kids. Most of the boys did have men that I presumed were their fathers. I had nobody. One other boy didn’t have anyone and I thought, ‘Oh, gee, where’s my father? Where is he? Why doesn’t he come?’

“There were other reunions. Lights were out in the dormitory and suddenly they went on and all these men appeared. Most of the men picked who their sons were.”

Elaine: “They were probably told, ‘Your boy is the sixth bed along…’”

Victor sincerely believed he would eventually see his father again.

“Zofia did tell me, ‘You won’t see your father, he’s not coming,’ but I thought maybe he was held up, maybe his train didn’t come… She didn’t tell me he was dead. She just said, ‘You won’t see your father, he’s not coming.’ I accepted that. I thought, ‘Oh well, okay.’

“After a while I realised there was no one coming for me but I still thought they might. The boy in the next bed, his father gave him some lollies, so he shared them. I thought, ‘Oh well, that’s nice.’”

Elaine: “When we were in Wellington, another of the boys, Tony Rybinski, said Vic was lucky: At least he had a sister here. Tony was separated from his sister. She went to Africa.”

Victor very nearly did not have Zofia in New Zealand. If matters in Persia had taken the turn that they so easily may have done, Victor may not have come to New Zealand either.

A woman in Persia had wanted to adopt Zofia. Zofia told her she had a little brother. The woman said, “I’ll take him too.”

Elaine: “Zofia told Mrs Budzyń, a neighbour from Hallerowo and Victor’s godmother, who told Zofia, ‘That lady does not want your brother. She only wants you. Don’t be adopted. Stay with your brother. Stay together. Stay with the orphanage. They have to look after you.’”

Victor: “Zofia was a very, very pretty girl when she was young.”

Victor and Zofia with Victor’s godmother, Mrs Magdalena Budzyń from Hallerowo. The photograph was probably taken in Isfahan, where three of Mrs Budzyń’s children were listed as living in one of the Polish hostels, Irena (born 1929), Eugeniusz (born 1932) and Ryszard (born 1934). Their father, Ignacy, died in April 1942 in the USSR soon after he enlisted for the Polish army and is buried at the Stacja Kermine cemetery.24

_______________

Once the Pahiatua Children’s Camp closed, Victor and the rest of the youngest boys moved to Hawera orphanage and finished what is in New Zealand now called intermediate schooling. An aptitude for chemistry may have been the reason why his guardians moved him to St Patrick’s College in Silversream, Upper Hutt, as a boarder.

“I’m not sure why I was chosen. I think it was the academic. About six of us went.”

“I ended up studying pharmacy. I was pushed into it because chemistry was my big subject. I didn’t know what to do with myself, so I thought, ‘All right, I’ll be a chemist.’

“The exams were easy. The first four years you were part-time in pharmacy school and part-time working in the shop, but it never interested me. Not a bit. I hung in there for various reasons. I was getting a small wage in those days, as an apprentice pharmacist.”

Elaine: “He paid his board and then the tram fare and had no money left. He had to patch up his shoes with cardboard.”

Victor: “After two years, I’d had enough. I didn’t like being in a shop all day. I had to say to the pharmacist, ‘Sorry, but I can’t finish this.’”

He soon found a job at the pharmaceutical supplier Messrs Sharland and Co. working himself up from the warehouse to a management position before moving to another wholesale distributor in Wellington, HF Stevens.

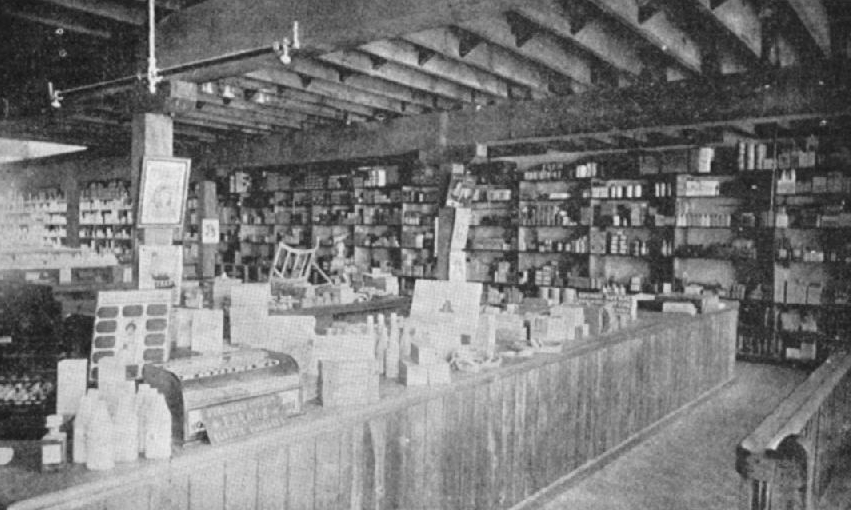

The patent medicine and sundries department at Messrs. Sharland and Co.25

_______________

Victor, third from left, with some of his fellow Pahiatua “river boys” dressed up for a Saturday night in Oriental Bay, Wellington.

At first Victor kept in touch with his Pahiatua friends.

“I was in a group of boys that were very close, all in a similar situation—no parents or not knowing where they were. We befriended one another. As we grew up, one or two boys would leave to go to work on a farm somewhere or go to university, and the group got smaller and smaller, so towards the end, I was on my own! A short time later, I’d gone into pharmacy.

“Zofia told me to join the Wellington Polish Association but I had no interest, although I did go to the dances.”

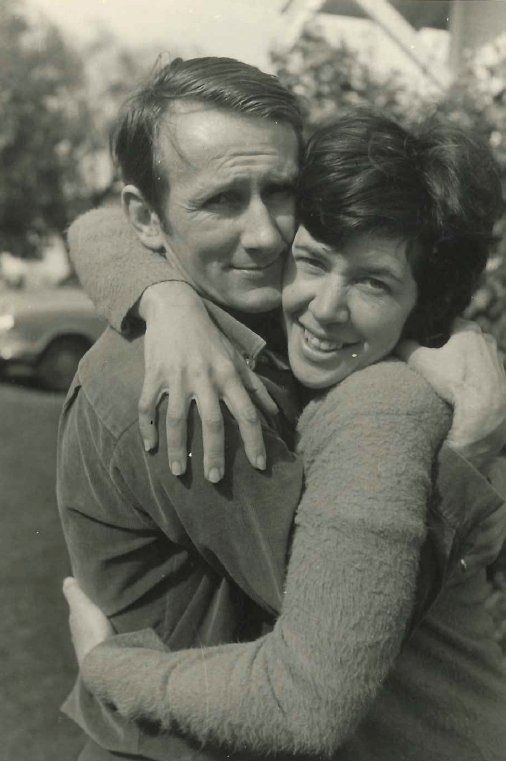

Victor and Elaine (née Tait) met at a Wellington jazz club. Elaine sat with a group of girls with whom she flatted and Victor was at the next table.

Elaine: “On my table, everyone else got up to dance and I was alone. I looked over and he was alone too, and I thought, ‘Oh dear, he’s going to think he has to ask me to dance.’”

Victor: “I straightened my hair, adjusted my jacket and walked over.”

Victor and Elaine Pleciak with their entourage at the Wellington Botanic Gardens on 31 October 1964. Edward Wała was best man and Elaine’s sisters, Daphne Mackie, left, and Nancy Greensmith were bridesmaids.

They were married in Kelburn two years later. Life continued comfortably until Victor’s employer relocated to Auckland. Their sons, Michael and Steven, were then aged eight and four.

“I had the choice to move to Auckland or look for another job, and I liked my job.”

Elaine, “cried for a week” at Victor’s decision. She reconciled herself by the fact that her parents and sister had moved from Silverstream to Auckland and later appreciated that she was available to help care for her parents when both developed leukaemia.

_______________

Zofia had married Henryk Wołk in 1952 and already lived in Auckland. Henryk died in Ellerslie on 17 October 2018.

His former business partner, Mietek Ptak, recalled that Zofia and Henryk’s friendship developed in the Pahiatua camp after they both took part in the Christmas jasełka (nativity) plays. Henryk played the violin during the performances. Henryk and Mietek met at the No. 1 hostel in Isfahan and left the Pahiatua camp together in January 1947 after they were enrolled in St Peter’s College in Auckland.

_______________

Victor: “Zofia told me we had a big sister and brother in England. I accepted it and left it at that. I thought, ‘Well, I’ve got other family,’ and I started thinking about my father, mother and what about the rest of them? Zofia didn’t tell me any of that, didn’t want to upset me, perhaps?”

Zofia flew to England in the late 1950s and met Jadwiga and Jerzy (by then called Jenny and George) and their families and Jenny twice visited her family in New Zealand. Victor visited Poland, the Ukraine and England in 2000, meeting his brother for the first time since Isfahan. George lived in Kidderminster and Jenny in Hereford.

“I stayed with my sister and part of her family because her older kids were grown up and had left home.

“George came over to meet me. I knew he was my brother, my own flesh and blood, but I had no close feeling towards him at all. I don’t know how to explain it. I didn’t know the guy, I didn’t remember him at all. We shook hands and we said, ‘Good day, how are you?’ Very basic stuff. There was no hugging or anything like that. We exchanged Christmas cards, just ‘Happy Christmas’ until he died.

“Jenny was more effusive, she was an absolutely lovely person, wonderful. She had eight children and brought them up without any parental help.

“Her husband, Zbigniew Pawłowicz, was a psychiatric nurse and took up photography to help with the family budget. I met them all when I was there. They were good kids. We had laughs.”

Jenny, who had waited in vain for news of her family in Teheran in 1942, never gave up her search for her surviving siblings. According to her wartime testimony, she first contacted Zosia by letter in 1943, before leaving with the Polish army for training in Iraq, then Palestine.

After more training in Egypt in 1944, Jenny joined a field canteen company that followed the Polish soldiers up the eastern Adriatic coast of Italy. She met George for the first time since Uzbekistan “somewhere between Forli and Bologna” a few weeks before the end of Italian hostilities.

Jenny moved to England in July 1946 and continued her high school studies for another year. She met and married then officer cadet Zbigniew in June 1947.

_______________

Victor cherished his own fatherhood.

Elaine: “He would deal with the baby in the middle of the night once we were feeding on a bottle; he’d be tucked in, everything tidy. Vic always took the boys to sports. Instead of playing golf or go out himself, like so many other dads did in those days, he drove the boys around everywhere for all their sports and rugby and tennis, cricket, fishing.”

Victor: “We had friends who had families, kids the same age as ours, who just didn’t look after them all that well. Their kids were doing their own thing. When ours were growing up, I tried to be there when I could.”

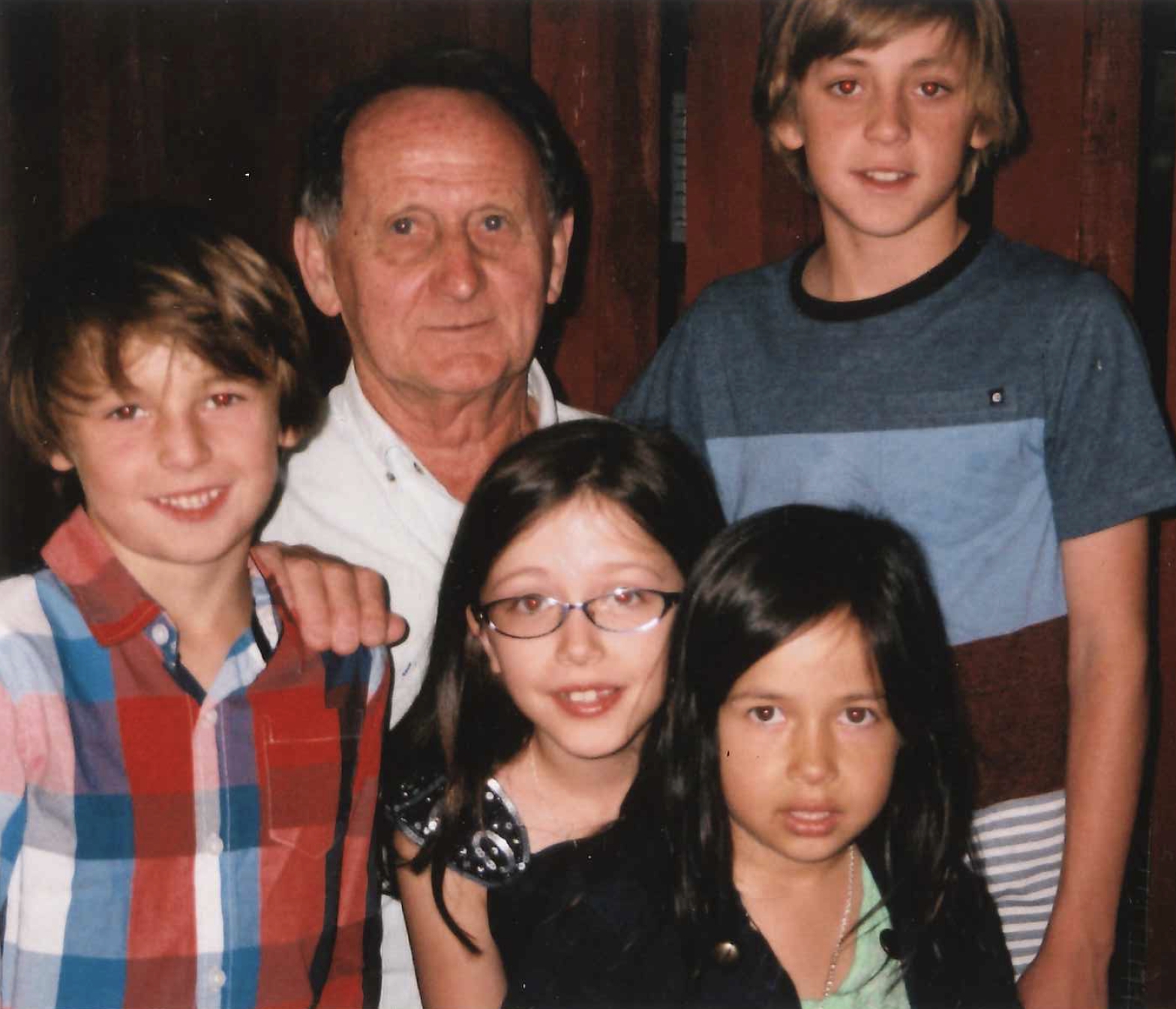

Victor and Elaine have four grandchildren, Thomas, Benjamin, Nina and Eva. Displayed in their home are several school projects they have made on Victor’s life and his Polish background. Nina, Michael’s 14-year-old daughter, made an audio recording of him as part of a project, for which she received a “beyond excellence.”

Victor with his grandchildren in 2014: Benjamin, left, Thomas, back, Nina, middle, and Eva.

It is clear that throughout his life Victor has bent with adverse circumstances, accepted what he could not change, and worked with what he could.

“Those early experiences definitely made me stronger. I think that being brought up as one of the ‘river boys’ in the [Pahiatua] hostel and then in the boarding schools, with all that strict, strict discipline, taught me to respect myself and the people around me.

“Respect. It’s everything.”

© Barbara Scrivens, 2018

UNLESS OTHERWISE ACKNOWLEDGED, ALL PHOTOGRAPHS EXCEPT THE COLOURED ONE IN THE INTRODUCTION COME FROM THE PLECIAK COLLECTION.

THANKS TO THE NORTH AUCKLAND RESEARCH CENTRE IN THE TAKAPUNA LIBRARY FOR THE LOAN OF AUDIO RECORDING EQUIPMENT.

ENDNOTES:

- 1 - We found Jadwiga’s deposition through the website Zapisy Terroru Repozytorium

Ośrodka Badań nad Totalitaryzmami, (Chronicles of Terror). Testimonies were collected by the Independent Historical

Office of the Command of the Polish Armed Forces in the Soviet Union/Documentation Office of the Polish Army in the East and

are held at the Hoover Institution archives.

https://www.zapisyterroru.pl/dlibra/publication/2568/edition/2549/

Jadwiga gave Victor a copy of her original and translated memoir. It appears in the book Z Kresów Wschodnich R.P. Wspomnienia z Osad Wojskowych 1921-1940 (The Eastern Borderlands of Poland, Memories of Military Settlements 1921–1940), published by OROK, Ognisko Rodzin Osadników Kresowych (Association of the Families of the Borderland Settlers), London, 1992 and 1998, ISBN 1 872286 33 X

http://www.kresyfamily.com/wow-063-hallerowo-pleciak.html - 2 - Information from the website Strony O Wołyniu,

http://wolyn.freehost.pl/miejsca-h/hallerowo-08.html - 3 - For more information, read The Eighteenth Decisive Battle of the World, by Viscount D'Abernon,

Hodder and Stoughton, Warsaw, 1920, and

White Eagle, Red Star, The Polish-Soviet War 1919-1920 and ‘The Miracle on the Vistula,’ by Norman Davies, my edition published by Random House UK Limited, London, ISBN 9780712606943. - 4 - Mapywig is a non-commercial project dedicated to the archiving of maps created by the Military Institute

of Geography 1919–1939. The map of Hallerowo and its environs can be found on:

http://maps.mapywig.org/m/WIG_maps/series/100K_300dpi/P46_S43_HOSZCZA_1930_300dpi.jpg - 5 - http://english.mapywig.org/news.php

- 6 - Ibid Jadwiga’s memoir.

- 7 - This location does not appear on the list of forced labour facilities that the Poles were sent to. It may have been an existing facility. Jadwiga’s spelling of place names is too accurate for her to have been far wrong.

- 8 - http://wolyn.freehost.pl/

- 9 - Information from the Strony O Wołyniu page and the Wikipedia page on the Okręg XII

Podlasie NSZ,

https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Okręg_Podlasie_NSZ - 10 - Ibid Strony O Wołyniu.

- 11 - Ibid Strony O Wołyniu.

- 12 - Translated from the copy of Stanisław Nieścior’s kwestionariusz that I received from the Hoover Institution at Stanford University in California.

- 13 - This website uses single quotation marks around the word “amnesty” to mark its irony. Stalin was not pardoning the Polish civilians he incarcerated for any wrong-doing on their part.

- 14 - In 1942, the Polish army evacuated 69,247 civilians and soldiers in two sets of transports across the Caspian Sea, from 25 March to 5 April and from 10 August to 2 September.

- 15 - “Junaczki” is a colloquialism for the military cadet school for teenage girls younger than 18, the SMO or Szkoła Młodszych Ochotniczek (School for Young Army Volunteers).

- 16 - If anyone can identify the photographer, please let us know.

https://tehran.mfa.gov.pl/en/bilateral_cooperation/polish_cemeteries/ - 17 - This photograph reproduced through the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike licence. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Polish_cemetery_Tehran_Barry_Kent.jpg

- 18 - According to other descriptions, the walls were much higher but Victor’s description matches perfectly their towering over a little boy.

- 19 - Image from New Zealand’s First Refugees: Pahiatua’s Polish Children, Polish Children’s Reunion

Committee, published in Wellington 2004 and available through the New Zealand Electronic Collection:

http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-PolFirs-t1-front1-tp1.html - 20 - Images of the Pahiatua children’s early years can be viewed through the National Library of New Zealand.

https://natlib.govt.nz/ - 21 - This image from Victor Pleciak but also available on the above site.

- 22 - Ibid, the New Zealand Electronic Collection.

- 23 - According to the Department of Statistics, 1,740 people lived in the borough of Pahiatua in 1941 and 3,250 in the surrounding administrative county.

- 24 - Information from Henry Sokolowski, Stowarzyszenie Polskich Kombatantow, Canada. A hand-written list of the

graves in Kermine and maps can be viewed at the Polish Institute and Sikorski Museum.

http://pism.co.uk/Docs/A_VII_13_t24.pdf - 25 - The Cyclopedia Company, Limited, 1897, Wellington, part of: The Cyclopedia of New Zealand, Creative Commons

Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 New Zealand Licence.

http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/Cyc01Cycl-fig-Cyc01Cycl0488b.html