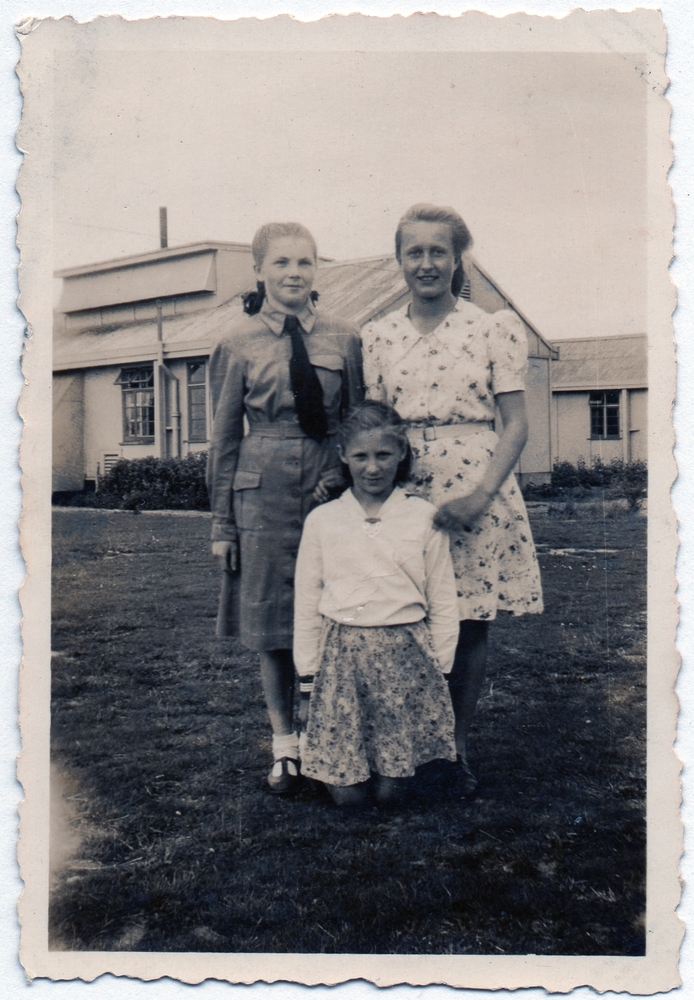

Zofia Iwan Derrick &

Irena Iwan Pąk

Irena née Iwan Pąk, left and Zofia née Iwan Derrick.

I first met Irena Pąk, her late husband, Jan, and her daughter, Wanda, in 2012 when they accepted invitations to a Polish lunch at my home. Pani Irena made my day when she said she liked my zupa szczawiowa, and I warmed to her even more for telling me that one can never have too much szczaw (sorrel) in that soup.

I appreciated seeing Pani Irena at Polish functions. She has the charming warmth of sincere people who put others before themselves, and always took time to chat. She was reluctant to talk about her childhood, so I appreciated the effort it took for her to sit with her sister, Zofia Derrick, and relive the toughest days of her life.

It was a pleasure to meet Pani Irena’s older sister, Zofia Derrick, and her husband, Ken, at their home in Auckland, where we made our first audio recording. Wanda, and Pani Zofia’s daughter Maria joined us.

Today, not one of us can say that we are unaware of refugees, of camps without food, water, or shelter, but filled with disease, fear, and pain. Images are there for us to see.

But in 1941 and 1942 the “western world” knew little of the conditions faced by hundreds of thousands of wrongfully incarcerated Poles in Soviet forced-labour facilities in the USSR, and suddenly released. They travelled thousands of kilometres, often on foot, to leave that inhospitable land. Too many of their stories are lost, forgotten with time.

I am so glad that these two wonderful women chose to talk about their experiences, and I thank them for their time and generosity.

—Barbara Scrivens

FORESTS, GOLD, SAND, AND AN ISLAND IN THE SOUTH SEAS

by Barbara Scrivens

Summers in arid, land-locked Uzbekistan are long, hot, and dry enough to extinguish the life in any natural vegetation. In 1942, thousands of ragged Polish refugees had spent months getting there in the hope of finding a new Polish army.

Uzbekistan became the chaotic corridor out of the USSR for the Poles, released from Soviet forced-labour facilities after Nazi Germany invaded Russia in June 1941.

The Poles mixed with impoverished Uzbekistanis, who could barely look after themselves, never mind cope with an influx of strangers competing for food.

In theory, the Poles should have been able to find one of at least 30 Polish military bases scattered along the Kazakhstan-Uzbekistan border, and leave the USSR.1

In reality, Stalin had planned to use the Poles to fight within his Red Army to defend Soviet Russia. When army-able Polish men left the forced-labour facilities with their families rather than on their own, Stalin refused to feed the Polish civilians. When Polish army commanders challenged his proposal to send under-prepared Poles to save Moscow, Stalin stalled Poles from reaching enlistment stations.2 As the Polish army pushed to get its citizens out of the USSR, Soviet trains disgorged Poles in some of the most inhospitable places in central Asia.3

The Poles were in the USSR thanks to Stalin. After his Red Army invaded Poland on 17 September 1939, until Hitler crossed into Soviet-occupied Poland on 21 June 1941, the NKVD—Stalin’s Secret Police—had engineered the capture of around 1.7-million Polish civilians and military personnel.

Those they did not murder,4 they deposited in prisons and forced-labour facilities scattered throughout the USSR. Poles older than 15 became part of Stalin’s third Five-Year plan to build infrastructure such as rail under a strict Bread for Labour regime. Poles who did not work were expendable, and it is estimated that nearly 700,000 had died by 1942.5

The future of Poles incarcerated in Stalin’s forced-labour facilities and prisons became more hopeful once Hitler made significant inroads into his former ally’s territory. Stalin saw the benefit of swapping to the Allied side, did so, and sent his ambassador to the United Kingdom to talk with Polish Prime Minister General Władysław Sikorski. The two signed an agreement on 30 July 1941, and the news began to trickle through to the hundreds of thousands of Poles in the USSR that they were free to join a new Polish army being formed in Russia.

London, 30 July 1941: British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, holding a cigar to his mouth, overseeing the signing of the Polish-Soviet agreement, which allowed Poles to leave Soviet forced-labour facilities in the USSR. From left, seated are Polish Prime Minister, General Władysław Sikorski, British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden, Churchill, and on the far right, Soviet ambassador to the United Kingdom, Ivan Maisky.6

By late 1941, the Poles were only too happy to leave their dire living and working conditions before another winter further increased their growing mortality rate. They soon learnt, however, that they walked into environments as bad or far worse. At least the NKVD provided a minimum of food in exchange for work. Once the Poles left to travel the thousands of kilometres south and south-west, they had to fend for themselves until they reached Polish enlistment station or civilian camp.

The Polish army then had few restrictions, because enlistment of one member of a family ensured the army had valid reason to help the rest of the family’s passage out of the USSR. The situation for those who did not reach the Polish enlistment stations became considerably worse.

Until they reached Polish authorities, the Poles were nomads in unfamiliar landscapes with little food, water, shelter, sanitation, or paid jobs.

_______________

The Iwan family joined the confusion in Uzbekistan that summer: WWI veteran Władysław Iwan (42) arrived with his wife, Leokadia née Szlendak (36), and their children, Zofia (13), Czesław (12), Kazimierz (9), Irena (7), and Zdzisław (4).

Among the milling crowds, Władysław managed to hang out some washing, and told Kazimierz and Irena to look after it.

Irena: “We went and had a drink of water and when we came back, the washing was all gone. My father gave me a hiding—I don’t remember Kazio getting it—and I was crying and crying. We hardly had any clothes and our clothes had been stolen.

“We children, we didn’t know what was happening, what was happening next. We were just going along.”

“I thought it was in Uzbekistan because we were living in a little mud hut. It was very, very, hot there, sandy under your feet. I remember the żółwie, the little turtles, or tortoises. Somebody was cooking them, and we were watching. The locals didn’t like us cooking them, but there wasn’t much to eat, and we were already weak from being starved in Siberia.”

That hiding is Irena’s only memory of her father, who disappeared soon after the theft of their clothes. The fact that she remembers her father hanging out some family washing suggests that her mother was ill. The absence of older siblings Zofia and Czesław suggests that they were ill too.

It is not clear what Polish army enlistment stations still operated in the summer of 1942. The Polish army had already carried out a first set of evacuations from the USSR several months earlier. Nearly 44,000 Poles, three-quarters of them military personnel, crossed the Caspian Sea to Pahlevi in then Persia, now Iran, mostly by cargo ships.7

Władysław may have settled his family in the hut while he hunted for the Polish army, but if he became ill and died without giving his name at a hospital, he would have been listed among the many “nieznany,” the unknown.

Zofia: “We children, we didn’t know what was happening, what was happening next. We were just going along. I remember we were waiting for something. I think it was in Uzbekistan. We looked for food wherever we could. It was self-survival. We had to beg, because what else do you do?

The people there and us, we couldn’t really understand each other—we communicated through some Russian we learnt in Siberia—but you put your hands out, and they knew what that meant, and they would have known about us. You see a hut, you go and see if you can get some food. In one hut, a man frightened me, and straight away, I ran out. Now, I don’t know whether he was bad, or trying to be kind.”

Irena: “I remember picking cotton, but I don’t remember anyone else from my family with me. I remember being on my own in the field. I can see it in my fingers—the soft white cotton, and the brownish husks that you had to pick off—but I can’t remember where my parents were then. We probably had to pick some quantity. We didn’t get paid, but we probably got some watery soup. I remember watery soup.”

Irena’s memories of the cotton harvest, usually in late summer, indicates that the authorities in charge of the collective farms in Uzbekistan purposely interrupted the Poles’ journey out of the USSR at that time, to use their labour for the harvest. Stalin’s alleged ‘amnesty’8 agreed to with General Sikorski, was then a year old.

Zofia remembers nothing of cotton picking, another indication that she had been ill.

_______________

The Iwan family was living a charmed life before the dual invasions of Poland in September 1939. Władysław Iwan had taken up a position as a forester in the Nurzec forestry district, about 75 kilometres from Osipy Kolonia (near Wysokie Mazowieckie), where his and Leokadia’s first four children were born.

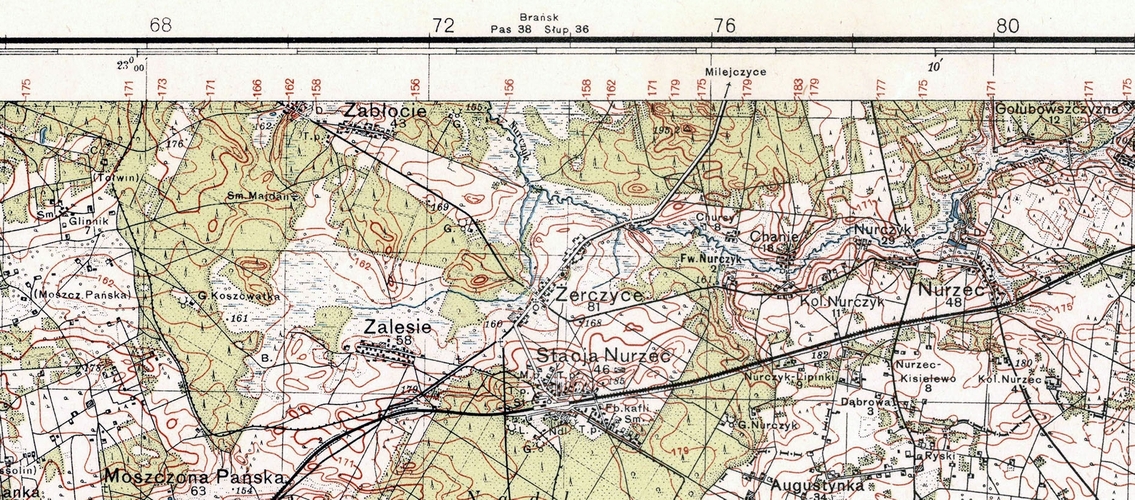

A slice of a map from the Polish Military Geographical Institute (Wojskowy Instytut Geograficzny), established in Warsaw 1919, which created detailed topographical charts of Poland after independence in 1918. It shows the general area of Nurzec and Stacja Nurzec.9

A close-up of Gajówka in 1937, which the Wojskowy Instytut Geograficzny, Warszawa, marked with just a capital G, sitting in a mixed forest of coniferous and deciduous trees between Zabłocie and Żerczyce. Zofia remembered a young oak plantation, which could have been the question-mark-shaped block sheltering the main building from the boggy ground adjacent to the Nurczyk river, which ran towards Żerczyce, about a kilometre and a half to the south-east.

Zofia: “The house was called Gajówka. My father was in charge of the upkeep of the area, and the house was given to him and his family to live in. It came with the job. It was surrounded by the forest. We could hear the trains from the house.

“We loved it there. It was nice place, a big place, stables, toilets away from the house. We had a cow and a horse, and I used to ride a bicycle around. We had plenty of provisions because mum used to make preserves of all sorts. They had a piwnica [cellar] separate from the house. They kept sauerkraut in big bins, ogórki [pickled gherkins], pickled food, bacon, smoked pork, beetroot, potatoes—all our supplies for winter.

“There were always mushrooms to pick, and all sorts of berries, little bushes of them, nice to eat, and I remember nuts too.

“The deer used to come onto the field, one corner. We loved them, but the pigs came too, rooting among the trees, looking for potatoes I think, so we used to chase them out as much as we could.

“I believe there was somebody living at the corner of the field where we had our cultivation, but I don’t remember ever going by myself over there, and there used to be a little village on the other side, but we couldn’t see the houses. We used to walk the other way, through a young oak forest, to go to school.

“Once, we lit a fire on the edge of the forest because we wanted to bake some potatoes in the ground, but the cow came around and Czesio got pushed a bit, into the charcoal. I carried him up and put him on the veranda and…”

Irena to Zofia: “That was me! The calf, or cow, pushed me into the fire and I got burnt, and I remember you put me on the veranda, on a bench.

“The parents weren’t home. They put me under a curtain, tried to hide me because they were scared. I remember that, and riding on the sleigh to the doctor, and crying when he was taking the bandages off. He offered me a lolly or something, and I didn’t want it because I was so sore. Years later I was telling Zofia, ‘I’m all sort of brownish here.’ And she said, ‘You were burnt.’”

“We had to run from the house and get into the forest, because the planes could attack houses…”

The sisters’ memories differ slightly as they experienced different aspects of their lives. Zofia—oldest child and aged 11 at the most—was possibly more worried about their parents’ reaction to the wounds than to the identity of the injured sibling.

Irena well-remembers their neighbour’s dog not recognising her and biting her on a leg and buttocks when they were playing dress-up and she was wearing her mother’s long frock.

Władysław and Leokadia Iwan may have tried to shelter their children from worry about the German invasion of Poland 10 days before Zofia’s 11th birthday, but they could not stop them from seeing the German planes that started flying over their farm.

Irena recalled their wujek Janek arriving to help their father build an underground shelter.

Zofia: “We had to run from the house and get into the forest, because the planes could attack houses. We used to watch the planes—there were quite a few. I watched one. I didn’t know what it would do. It tilted a bit, then this longish thing came out from underneath. It wasn’t opening, so I knew it wasn’t a parachute. Then I heard a bang, and I knew it was a bomb. I’m not sure whether it was over Nurzec, or the railway, but they wanted to destroy the railways, so the Poles wouldn’t be able to transfer their soldiers from one place to the other. They would also drop bombs if they saw trucks.”

_______________

After Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union divided Poland between them, Gajówka came under Soviet occupation, but the family living in and looking after the forest seemed to be left alone—until the following summer.

Zofia: “Dad wasn’t home. People came to the house and said that we were being taken to Siberia. It was during the day, and it was warm. I don’t remember them as soldiers. They told us, take a few things, go as quick as you can, you haven’t got much time. Mum was frightened. They gathered the children together, and Mum was packing.

“Dad was nearby in the forest. Someone must have told him what was happening. He went back home to give himself up, to be with his family. We took some bundles, only what we could carry. I don’t remember how we got to the train station. Maybe it was by cart, because we had a horse.

“There was nobody else in the family… taken to Siberia. Was it because my father was in the army, and then given a sort of government job?”

“We were on that train for about a month, getting closer and closer to Siberia. We changed trains at the border, and I remember a junction with different levels. We were on the higher level, and we could see people walking below.

“At the end, they took us on sledges to the area where my father worked, down there in a gold mine. In the wintertime, he went to work and came back with his clothes frozen. There was a sort of hot water cupboard down the steps, and we used to try and get him to loosen his clothes so he could take them off and warm up in there.

“First we were put two or three families into a dwelling, then the men built some little houses.”

Irena: “Cabins.”

Zofia: “There was a shop, and you could buy something from it, if you had a coupon, if you worked. Mum, just to get some food, used to go out through the forest to find the village, and take some clothing or something with her, to exchange for food.”

The Iwan family seemed to be as isolated in Siberia as they were in Gajówka. Zofia does not remember what the children did to occupy themselves, nor any kind of schooling, but no specific traumas either.

Irena: “I’d love to remember more. I’d love to remember how I was, or see myself in Siberia, know what sort of a child I was, what was happening to me, but that bit is all gone.

“There was nobody else in the family, as far as I know, taken to Siberia. Was it because my father was in the army, and then given a sort of government job?”

The family’s extraction from Gajówka seemed to veer from the norm.

First: It was unlike the NKVD to round up families in daylight. The reason Stalin gave for the mass deportations of Poles after his invasion of Poland, stemmed from their new classification as “anti-Soviet elements.” In “Strictly Secret” order No. 001223, 10 pages of instructions included that the “operation shall be carried out… at night-time” so as not to alert neighbours.10 Polish families simply disappeared. Night-time also meant that a targeted father was likely to be at home in bed.

But—the NKVD had carried out the first mass expulsion of Polish families in February 1940, so by the summer of 1940, during the third wave of mass expulsions, the NKVD had lost the element of surprise.

Second: Władysław was not a military settler who had taken up land in eastern Poland after the Poles won the 1919–1920 Polish-Soviet War. Stalin had not had the most exemplary of campaigns in that war and, 20 years later, still held a particular grudge against those settlers.

Władysław had served in the battle for Poland’s eastern borders immediately after WWI, but had not taken up the offer of land in eastern Poland afterwards, so could not have been considered one the Polish military settlers, whose families the NKVD rounded up in February 1940.

Władysław Iwan was born in Huta, Wola Czołnowska, north of Lublin, in February 1900. His parents were Filip Iwan and Franciszka née Rybak Iwan.

Third: Besides not being a landowner, he was not attached to an overt military unit, nor part of a constabulary, nor judiciary. But—he was a forester living what might have been considered by the Soviet regime, a comfortable life.

A post-WWI Poland, newly independent after 123 years partitioned between Prussia, Russia, and Austro-Hungary,11 built up a forestry industry that within 10 years covered more than 3.3-million hectares. By 1939, the forestry sector had modernised, had educated its employees, and had become a significant part of the Poland’s domestic economy.12

An estimated 11,000 foresters fought in WW2, and 724 were murdered at Katyń. During the war, foresters were known for hiding partisan troops among their trees, putting themselves and their entire families at risk of execution by the German and Russian occupiers.13

Even if the NKVD had not targeted the Iwan family for Władysław’s job as a forrester, it may have found Władysław’s WWI and Polish-Soviet War records in Warsaw, or his 1936 application for the Polish Independence Medal.

He was just 16 when he joined Józef Piłsudski’s Polish Military Organisation (Polska Organizacja Wojskowa, or POW) in April 1916.14 The POW gathered intelligence and sabotaged enemies for Piłsudski’s Polish Legions, and by 1918 had more than 30,000 members.15 Władysław used the pseudonym Sęk (wood knot).

The commemorative badge that was awarded to veterans of Józef Piłsudski’s Polish Military Organisation (Polska Organizacja Wojskowa, or POW), whose initials are in the centre. It is not clear whether Władysław received is cross, but he was allocated number 21,660.

Władysław’s last duties with the POW in December 1918 included helping to disarm units of the German army in Tykocin, Rzędziany, and Osowiec, west and northwest of Białystok, and in Białystok itself. He then joined the new republic’s new Polish army, which posted him to its 33rd Infantry Regiment at Osowiec-Twierdza, with whom he fought the Bolsheviks for the Polish-USSR border.16 He was discharged from the army in 1923, and returned to the Osipy Kolonia northwest of Wysokie Mazowieckie, where he settled down among family.

Władysław was the second of five siblings, a year younger than Jan (the wujek Janek who helped with the underground shelter), and older than Piotr (Irena’s godfather), Theofil and Marysia. When their father, Filip, died in 1926, his death certificate recorded Jan and Władysław as farmers.

According to their marriage certificate, Władysław and Leokadia had married in the Catholic church in Wysokie Mazowieckie exactly two weeks before Filip’s death. Leokadia’s parents, Józef Szlendak and Rozalia née Zabieglińska Szlendak, were also farmers in Osipy Kolonia.

Zofia recalls a large family in Osipy Kolonia. Four different Iwans and three different Szlendaks as godparents to Władysław’s and Leokadia’s first four children supports their close family ties. Władysław’s move away from those bonds indicates that he considered the new job in Gajówka as a worthwhile career move in the burgeoning industry.

Family story has Władysław re-joining the POW in 1936, so perhaps in the summer of 1940, Sęk had been betrayed by someone local who did not appreciate the newcomer in the district—Zdzisław had been born in Nurzec in January 1938.

To transport around 900,000 civilian Poles in 1940 and 1941, the NKVD used former cattle trains, modified with slats against the walls for people to sleep, a pot-belly stove, and a hole in the floor.

In June 1940, there happened to be one such NKVD mass deportation train travelling through Nurzec from Siemiatycze to the USSR.

Without records it is impossible to know exactly where the Soviets deposited the Iwans, but sending a family to a gold ‘mine’ is not far-fetched:

The USSR mined gold at an incredible loss in the 1930s, apparently because the Soviet government believed the “capitalist world economy” could not function without it. More than half the Soviet’s 1930s production came from quickly exhausted placer deposits, which could be worked by hand by citizens encouraged to mine them, so it is feasible that Soviet officials appreciated the free Polish labour.17

_______________

The Iwan’s sketchy last few months in the USSR marked the end of their family unit. Zofia recalls leaving the gold mining facility on a type of kayak down a river, then walking, and catching trains.

Zofia: “A lot of Polish people were on a train. I remember people waving at me, and I was waving to them, and we were walking, walking out of there, and waving.

“Mum worried—and dad—and they looked after us. They were with us all the time in Siberia and, somehow, we managed there, and then for quite a bit when we got out, but it was flat and dry… We were living in another little sort of hut, made out of dirt and stones.

“Mum wasn’t well. She had pleurisy. They put little glass bottles on her back to draw out the fluid in her lungs. She recovered a bit. There was a Polish man there, so desperate to get to Poland, ‘Poland, Poland, Poland,’ he kept saying. That was towards the end [of their time in the USSR] and then we crossed that sea, and mum was still alive.”

Irena: “It was on a cargo ship. I was feeling the heat, and I think we just slept on mattresses. There were no beds.”

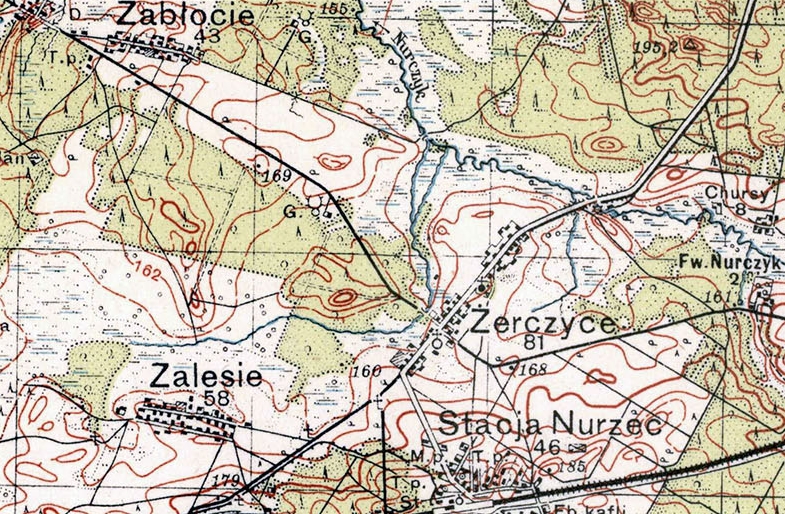

The Red Cross recorded the names of civilian Poles who boarded the various shipping vessels that left Krasnovodsk in March–April and August–September 1942. There were only 157 names beginning with an I on the main list, and none in the supplementary sections. Zofia, Czesław, Irena and Zdzisław were the only Iwans. But people did slip past the record takers—like those who arrived at the last minute, or others who worried they may not be allowed aboard if they showed symptoms of illness.

The Iwan siblings’ entries in the Red Cross list, Osoby Wyewakuowane z USSR 1942 (People Evacuated from the USSR in 1942), shows they were destined for civilian camps in Africa.

The sisters knew that they had had to leave Kazimierz behind, but cannot remember where or exactly why. He had apparently been too ill to accompany them out of the USSR. He may have died, and Władysław and Leokadia did not inform his siblings. Władysław may have stayed behind to look after him. Zofia likes to think he may have become separated from the family, and found his way to England under a different surname.

Zofia recalls her brothers being on “other transports,” so Leokadia may have done what many parents who could not feed their children did—trust some of them to a Polish orphanage. Families then separated through sheer desperation.

Leokadia née Szlendak Iwan was born in Kośmin in February 1904. Her father was Józef Szlendak and her mother was Rozalia née Zabieglińska.

It is unclear when or where Leokadia Iwan died. Irena does not remember her mother at all, and does not accept that she made it out of the USSR, but Zofia witnessed her mother’s death, and believes it was in Pahlevi, after she delivered her children out of the USSR:

“After my mother got sick, and she was lying there, and I got sick, and I was lying beside her, she just quietly died. I think we were waiting to be attended. They attended to me finally. The Americans were there, so they must have been helping the Poles. We were somehow feeling safe by that time, because we were out from [the gold mining facility] and we were among Polish people and other friendly faces.”

Zofia had several bouts of illness. She remembers watching films with other Polish children: “I don’t know where it was, but I was shivering and shivering and stayed in the theatre. They must have taken me out.

“Once, when I was ill, some soldiers came to me and asked me if I would talk to the Russian soldiers. I kicked up such a fuss. They didn’t realise how frightened I was of Russian soldiers. Finally, they said, ‘It’s all right,’ and left me alone.”

Once the Poles arrived in Pahlevi—around 115,000—military authorities processed them through sanitation stations, and on to hospitals and various military and civilian camps in Persia.

Irena: “I had my First Holy Communion in Pahlevi. I was in a tent, lying down one evening when they called me to confession. What kind of a confession could a child my age have? After what we had been through? What could we have done? I remember standing in the sand, shuffling the sand with my feet, and getting my First Holy Communion.”

The Shah of Iran organised about 25 large houses in Isfahan to serve as Polish orphanages. The first 250 children were settled there in April 1942, immediately after the first sea crossings from the USSR. By February 1943, the city held 2,590 Polish children and caregivers. When 836 children and staff left for New Zealand in September 1944, 1,152 remained. The last Poles left the Isfahanian hospitality in April 1945.18

Zofia, then 14, tried without luck to find her father and Kazimierz through the Red Cross, which was uniting splintered Polish families. Because of the differences in ages and sexes, the Iwan siblings did not live together, and only luck kept them in the same country: The Red Cross list evacuation recorded all four siblings as destined for Africa. Zofia later found out that a woman who happened to know her and Irena, saw Czesław about to board a bus with children headed for South Africa, and stopped him.

The Polish authorities divided the children by ages and sex, which parted the four Iwan siblings who had played together in the Gajówka forest.

Irena, who arrived in Pahlevi a month before her eighth birthday, sorely missed her brothers and sister. She did not see her brothers in Isfahan, and remembers her sister mainly through Zofia’s gift of a painted shell brooch, bought from a city shop.

The brooch that Zofia gave her sister in Pahlevi. The memento is Irena’s oldest possession, now in the care of her daughter, Wanda.

Isfahan suited Zofia, who had more freedom. She was happy there, came to know the city well, and expected to remain. She remembers a woman who played the violin, and that she and her daughter returned to Poland.

“I loved to walk by myself through the streets. I loved watching the tradesmen doing their work, inside the shops, making the jewellery, and the rugs.

“We were given a house, upstairs and downstairs. We were upstairs and the back of the house had a lot of trees. With all that heat, they made places where you could go for a walk. It was no forest, but you could take a stroll, and we used to go out there and look at the view.”

Irena: “We met the Shah. Everybody says that he was very kind to us, and I believe he was kind to accept all these children, to look after them.”

_______________

Finding out that they were to go to a place called New Zealand came as a surprise for the sisters, and other children. They found the island in the south Pacific, almost on the opposite side of the world from where they were born.

Zofia: “New Zealand? First, we were going to this dot in the South Seas, then we found out we were going to Pahiatua. Where’s Pahiatua? We went through Palmerston North and people were waving to us.”

Even though the authorities at the Pahiatua Polish Children’s Camp knew that Zofia, Czesław, Irena, and Zdzisław were related, they lived in different dormitories. Families with parents lived in their own homes in the middle of the camp, or together in dormitories, but the several families of siblings without parents fitted in with the general demographics.

Irena: “There was no family connection. You are just another child. You might not see your brothers or your sister for quite a while, especially the brothers because they were on the other side of the camp. When my sister got married, that was my family. That was when we started to be a family again.

“When Zdzisio came to Auckland to live and I was eventually earning some money—not much because you had to pay board—once every few months I would meet him to go the pictures, to try to build family. And then Zofia went to Rotorua, Zdzisio went to Wellington, Czesio went to Taupo, and I was in Auckland, but we started keeping in touch with each other, building a sort of a family.”

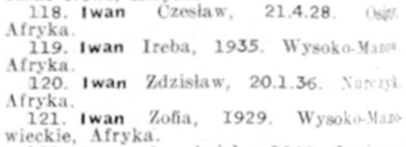

This photograph of Zofia, Irena and Czesław Iwan, was taken shortly after they arrived at the Pahiatua Children’s Camp. The sisters do not remember why their younger brother, Zdzisław, was not with them.

Zdzisław Iwan was not yet seven when he arrived in New Zealand in November 1944. The Pahiatua Children’s Camp is in the background.

The New Zealand government under Prime Minister Peter Fraser established the Pahiatua camp as a temporary refuge for 733 Polish children to see out the war with their 105 caregivers, but their status changed after Poland’s so-called allies negotiated the country into Stalin’s communist control.

By the end of 1945, New Zealand’s responsibility for the children became more serious. Peter Fraser invited the Poles to remain in New Zealand and arranged that the orphaned children be allowed until they were 18 to make their own decisions about whether to return to Poland. In the meantime, the children’s curriculum began to include English.

Irena: “I can’t remember the first couple of years in Pahiatua, but we progressed. I remember more from Standard 5 and Standard 6. We had Polish classes and one class of English, which we started learning with nursery rhymes.”

Sixteen when she arrived in New Zealand, Zofia struggled more than Irena with the new language:

“I used to go with my friend Halina Rącza to Masterton, to a couple who took in children from Pahiatua to give them a little holiday. I couldn’t speak English, but Mrs Cockroft had this budgie, and this bird learnt Polish, and so did Mrs Cockroft. Fast! I thought, how come I wasn’t that good at English? Mr and Mrs Cockroft stayed friends all my life and came on holiday to us when we were living in Rotorua. They were a lovely couple. She belonged to the Red Cross.”

Zofia joined the Girl Guides in Pahiatua. She does not remember the name of the girl standing next to her, but Irena is kneeling in front of them.

Zofia, in the hat, with some of the older girls at the Pahiatua Childrens’ Camp in 1946.

Zofia left Pahiatua permanently to attend the Sacre Coeur Girls’ School (now Baradene College of the Sacred Heart) in Remuera, Auckland, as a day scholar. She boarded with the Purver family in Newmarket. Czesław followed a year later but lived with the Daley family in Ponsonby.

In 1949, when the Pahiatua camp closed its children’s section, Zdzisław moved to an orphanage in Hawera with the youngest boys, and Irena finally got the chance to live with Zofia.

Irena: “That was the first time we were together. We slept in the double bed. I had just turned 14.

“We called Mr and Mrs Purver, Pan and Pani. In the summer of 1949, Zdzisio came to visit us for Christmas. This is the only photograph we have of us together as children. I gave a copy to Pani, and her granddaughter Teresa found it after she died and gave it back to me.”

The Iwan siblings celebrated Christmas 1949 together, for the first time. Zdzisław had been allowed to visit his brother and sisters in Auckland. Zofia, at the back with Czesław, was by then enrolled in a business course.

The Daleys took in Leszek Wierzbicki as well as Czesław, and when Zdzisław left Hawera with Leszek’s brother Jurek, the Daleys also took in both younger brothers.

Zofia: “The boys must have been all right, because Mrs Daley’s son married a Polish girl [Anna Mielczarek].”

Irena was protective of her sister: “Ken [Derrick] came courting. He wanted to see Zofia. I said she’s not home, and slammed the door. Zofia came home and asked Ken why he was waiting in the street.”

Ken: “Irena wouldn’t let me in.”

Irena: “How would I know? She wasn’t home and I wasn’t going to let him in.”

After school and a business college course, Zofia worked at the Catholic Social Services, which looked after the settlement of the 200 Polish orphans who arrived in the Auckland diocese.

Zofia: “Not that I was great in English, or a fast [typist] like some people with 80 words a minute, but I got the job, and I was happy there. Ken was with the Youth Movement, and somehow or other he was interested in me. I was very shy, but Ken started coming around more often.

“But there was this Polish soldier in Tasmania. He was writing to me at the same time. He was ready to come over, and he sent me £100.”

Irena: “He even offered to look after me, and said that I would live with them in Tasmania as well.”

Zofia: “Ken wasn’t having any of that. He just went and bought a ring. Doctor [Rev Dr] Delargey, who became bishop later, married us at St Michaels’s church in Remuera. And we’ve been married for 71 years. I think we must be the oldest couple in the Takapuna parish.”

Zofia and Ken Derrick, at their home in Milford in 2021.

Although Irena married a Pahiatua ‘boy,’ she may not have met him at all had it not been for a mix up with his name and a friend’s.

Irena: “In camp, we heard that a serviceman was coming from England. My friend Zyta Bąk thought it was her father, but it was Mr Pąk, and I heard about his son Jan Pąk. He was already in Auckland, but he came to the camp for a holiday, because they were allowed to come once a year or something, and I met him then. When I came to Auckland, he was in Auckland, and we met again at Polish Mass and socials. I was about 17 when I went out with him to a show at the Western Springs showground on the 31st of January. I still remember the date. We went out for a little while, caught up again years later, and got married.

“I had other boyfriends in-between and was nearly engaged to a New Zealander, a school-teacher, but I broke it off because he was protestant and his parents wanted me to change my religion.

“I met them in Hastings at his sister’s wedding. The parents had a talk with me, told me they would like me to change my religion, because ‘it would be better.’ When I came home, I wrote him a letter and said we were not getting engaged. I was probably around 20 then.”

Zofia: “They wouldn’t have a show, thinking any of us [Iwans] would change religion. I always thank God for looking after us, that we stayed together, except we lost Kazio. Because of my religion, I could make decisions that I had to make. I looked at the person [who wanted to marry me], what sort of character he was, because that was going to be my life. I didn’t have parents to call, to run away to their house if things went wrong.

“All that we went through, it taught me that you really have to protect yourself, think about your life.”

Irena: “You had to make your own decisions because you had to do that after leaving camp. Practically, it was very hard. You don’t want to rely on anyone else because your whole life you’ve been making your own decisions. In Pahiatua we had rules: when to wake, when to eat, when to go to school, but not somebody else telling you what to do. That’s a different thing. You had to have rules, and you tried to keep them, and you were hard-working, because you had to be, but you couldn’t rely on anyone else.”

Jan Pąk and Irena Iwan, at a function before they married on 1 November 1958 at St John’s church in Parnell. Irena chose their wedding date specifically, as it represented her new life in New Zealand 14 years previously.

Irena and Jan, who died in 2014, were married for 55 years and had five children, Michał, Kazimierz, Wanda, Jan, and Marian, and nine grandchildren. The name of Irena’s first great-grandson, William Charles, tickles her because her brother Zdzisław changed his name to William and Czesław was always called Charlie. Zdzisław died in 2004, and Czesław in 2017.

Wanda’s birth changed Irena’s mind about having daughters:

“I wanted six boys, because I wasn’t very happy with females when I was 14, 15, 16, and had friends who always boasted about what they had. I was an orphan, and at Christmastime, or birthday times, they would skite about what they got. I thought, if I get married, I don’t want daughters, because this is what they’ll be like, but when Wandzia arrived, she was so different, such a lovely change. I wanted more girls, and I got another two boys!”

Jan and Irena Pąk and their children, taken at Christmas 1971. From left to right, the children are Michał, Jan, Marian, Wanda, and Kazimierz.

Zofia and Ken have 10 children, seven of their own, two they adopted and one who adopted them: Michael, Maria, Margaret, Mark, Paul, Patricia, Peter, Christopher, Julian, and Karen.

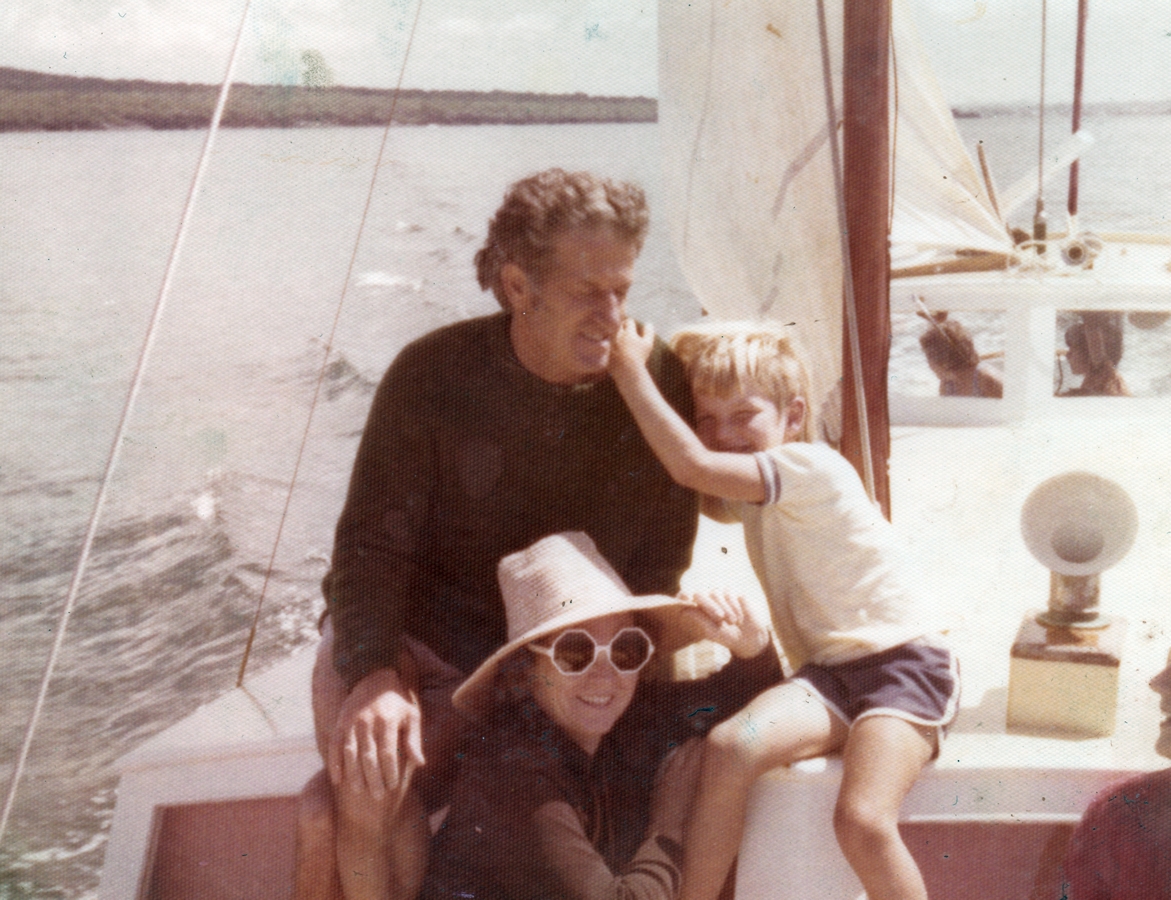

Zofia and Ken share warm memories of holidays with their children aboard their various sailing boats, here with their youngest, Julian.

The sisters banter and tease each other, and chuckle through their few disagreements. When I ask Irena for a word which sums up her life, she does not hesitate: Resilience.

Their deep hurt at the loss of their parents and brother in such tragic circumstances affected them deeply, but they both found ways to cope. And with that coping came strength that would challenge anyone.

© Barbara Scrivens, September 2021.

THANKS TO THE TAKAPUNA BRANCH OF AUCKLAND LIBRARIES FOR THE LOAN OF AUDIO RECORDING EQUIPMENT.

APART FROM THE RECENT PHOTOGRAPHS OF THE SISTERS, AND ZOFIA AND KEN DERRICK, ALL THE PERSONAL PHOTOGRAPHS COME FROM THE FROM THE DERRICK-PĄK FAMILY COLLECTIONS.

ENDNOTES:

- 1 - For a map of Polish military bases in Soviet South Asia, see Isfahan, City of Polish Children, page 14. Edited by Irena Beaupré, Danuta Waszczuk-Kamienicka, and Jadwiga Lewicka-Howells, Association of Former Pupils of Polish Schools, Isfahan and Lebanon, printed by Caldra House Ltd, Hove, Sussex.

- 2 - For more on the general difficulties the Polish army faced, see General Władysław Anders’ An Army in Exile, chapters X and XI, reprinted in 2004 by The Battery Press, Nashville, Tennessee.

- 3 - For more on the conditions in places the Poles were sent to, see In and Out of Nowhere,

https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/in-and-out-of-nowhere/ - 4 - See Katyń, The Unspeakable Crime,

https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/katyn-the-unspeakable-crime/ - 5 - Ibid, Anders, page 116.

- 6 - This photograph from the Anders collection, through the Polish History Museum in Warsaw.

- 7 - Pahlevi numbers.

- 8 - In 1941, Stalin made the grand gesture of declaring amnesty for the Poles he had incarcerated. I put the single punctuation marks around the word ‘amnesty’ to show its incongruity with the Poles’ situation: An amnesty is an official pardon for people who had committed offences, and the Poles in the USSR had done nothing to deserve their incarceration.

- 9 - From the Archiwum Map Wojskowego Instytutu Geograficznego 1919-1939, through Mapywig. This map of

Siemiatycze, PAS 39, SŁUP 36,

http://maps.mapywig.org/m/WIG_maps/series/100K_300dpi/P39_S36_SIEMIATYCZE_1937_300dpi_bcuj298395-288477.jpg - 10 - Tadeusz Piotrowski, editor of The Polish Deportees of World War II: Recollections of Removal to the Soviet Union and Dispersed Throughout the World, re-printed in full Serov’s Instructions Regarding the Procedure for carrying out the Deportations of anti-Soviet Elements from Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia. Mcfarland & Company, Inc, 204-209.

- 11 - I have taken the number of years after the third and final partitioning in 1795. The first was in 1772.

- 12 - https://www.lasy.gov.pl/en/our-work/sf-national-forest-holding/history

- 13 - Ibid.

- 14 - From his application to the Office of the Committee of the Independence Cross and Medal in Warsaw, dated May 1938.

- 15 - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polish_Military_Organisation

- 16 - Ibid, Władysław Iwan’s Independence Cross application.

- 17 - Soviet Gold Production, Reserves & Exports through 1954, pages 46–47. The report does not mention

Polish labour in 1940-1941.

https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/DOC_0000496246.pdf - 18 - Ibid, Beaupré, Waszczuk-Kamienicka, and Lewicka-Howells, page 127.