Commander Wojciech Francki

“WORTHY OF NOTE”

by Barbara Scrivens

On an overcast February in 1956, 52-year-old Wojciech Francki drove his Jeep to Auckland’s only civilian airport at Whenuapai. His passenger was 59-year-old Michał Pąk, who had not seen his wife, Zofia, or their son, Michał junior, for 16 years.

Michał junior came to know the man behind the steering wheel as Commander Francki,1 but he had no inkling of his heroic war record. Michał heard later that his father’s friend had worked on Polish ships in WW2, but not much more.

Wojciech Francki did not boast about his naval career, nor his actions on the night of 4–5 May 1942, actions that led to his third Krzyż Walecznych (the Polish Cross of Valour), a DSM (Distinguished Service Medal) from King George VI, and the destroyer ORP Błyskawica receiving the Gold Cross of the Order of Virtuti Militari, Poland’s highest military decoration for “heroism and courage in the face of enemy at war.”

The ORP Błyskawica and its crew is still remembered with gratitude by the people of Cowes and East Cowes on the Isle of Wight, and on this 80th anniversary, the towns have planned several commemorative events.2

This photograph of Commander Wojciech Francki, aged 38, on the ORP Błyskawica, was enhanced by The Polish Navy in Colour.

The Friends of the ORP Bylskawica Society has documented the testimonies of residents who recalled the night they assumed that approaching enemy airplanes were heading to the mainland—until they heard the air raid sirens, felt the bombs, and realised that they were the targets.

On 4 May 1942, the ORP Błyskawica happened to be docked at the J Samuel White shipyard at East Cowes, undergoing renovations at the place she was built six years earlier. Renovations included repairs after a surprise reconnaissance mission by three pairs of clearly marked Luftwaffe planes flew over the towns the week before. Two pairs dropped bombs on the Saunders Roe aircraft factory and the shipyards on either side of the Medina river. The middle pair flew along the river, then doubled back and dropped bombs on each side of the ship.3

The attack lasted less than a minute and was over before the towns’ air raid alarms activated. The ORP Błyskawica retaliated with its 40mm Bofors guns and 13.2mm Hotchkiss machine guns, but the bombs destroyed its mast and its torpedo control, “seriously damaged” its RDF (Range and Detection Finding) capabilities, and left the ship battered.

Various reports of this attack and the far more serious one in early May say or hint that Commander Francki disobeyed a British Admiralty directive to remove arms and ammunition from ships undergoing repairs. Apparently, the British navy was running low on both, and the Admiralty felt supplies were best used on vessels in active service. President of the Friends of the ORP Błyskawica Society, Geoff Banks, has another reason for the Admiralty not wanting ships with munitions in residential ports:

“The concern was that an enemy attack could result in a major explosion on the ship with a loss of the vessel and numerous civilian casualties.”

It is not clear what Commander Francki thought of a strategy that would leave one of the fastest warships—it recently escorted the RMS Queen Mary across the Atlantic—vulnerable in a dockyard on an island so close to Portsmouth and Southampton. The commander recognised the six Luftwaffe planes as a precursor for a more serious mission, knew the ORP Błyskawica, the shipyard, and the aerodrome had been targeted, and approached the Admiralty for permission to re-arm. When it refused, apparently despite his report, he ordered his munitions from Portsmouth, which obliged.

In his report to the London command of the Polish Navy “North” about the May battle, Commander Francki praised his officers and crew for their courageous efforts, and nominated four for “special distinction.” He told his London headquarters that after the battle, he was approached by the director of the shipyard, the town’s Chief of Police and individual people, who all echoed the conviction, “If it were not for you, we would have died here.”4

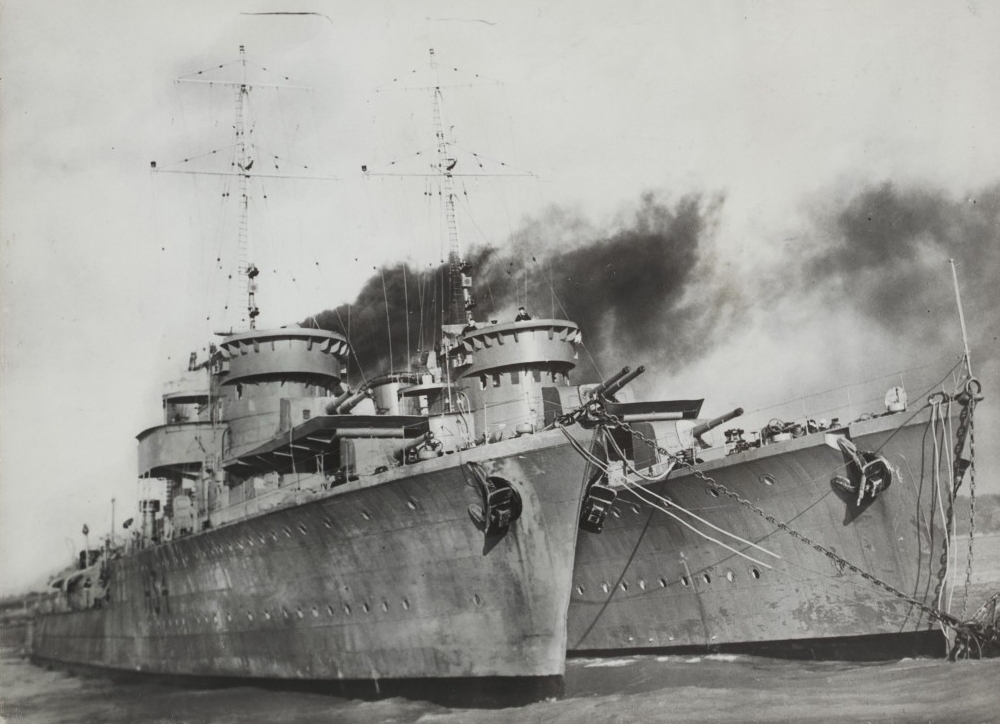

The ORP Grom (Thunderbolt) and ORP Błyskawica (Lightning) were built by the Samuel White shipyards in Cowes. ORP Grom gave her name to the Grom-class destroyers. She was launched in 1936 and sunk, by a German bomber during the Norwegian Campaign, on 4 May 1940.

_______________

Perhaps the Nazi strategists knew of the British Admiralty’s directive regarding the removal of munitions from ships undergoing repairs. Perhaps they overestimated the damage their reconnaissance planes did to the ORP Błyskawica six days earlier. Perhaps they simply underestimated the ship’s crew and dismissed the hurried retaliation of the Bofors and Hotchkiss guns.

On 4 May 1942, the first of an estimated 160 Luftwaffe bombers appeared from the south a few minutes after the towns’ air raid sirens woke its residents at 10.55pm. The bombers dropped flares, then incendiary bombs along both sides of the Medina.

In his report,5 Commander Francki recalled how, by 11.15pm, his ship was “surrounded by fires, which excellently illuminated the entire shipyard.” He sent three of his men to ignite smoke buoys at the “leeward quay” to mask the light from the flares and the fires, and give some cover to the towns and dockyard. He sent his “Leading Signalman” to the towns’ ARP (Air Raid Precautions) headquarters to offer help and his ship as a First Aid post for the lightly injured. He sent 20 men to help fight the fires in the dockyards, 30 men to help fight the fires at the Saunders Roe aviation factory, and another three groups of men to help fight the fires on the other side of the river. By 3.25am, he had sent the ship’s doctor and a medical unit to help at ARP headquarters.

The smokescreen hindered the Luftwaffe. The crew remaining on the ORP Błyskawica used the towns’ searchlights and the whistling of their engines to pinpoint and “constantly fire” at the enemy planes as they nose-dived before releasing their bombs. The ship’s 40mm Bofors anti-aircraft guns became so hot that crewmen bucketed water from the river to throw over them. Although the ship could not use its main guns—the earlier Luftwaffe raid had immobilised the rangefinder—the Bofors were supported by the machine guns, which fired 10,500 rounds. Free French naval units, also fired from their vessels farther up the Medina.

The barrage of gunfire from the ship forced the enemy planes to a higher altitude and reduced their accuracy. Commander Francki’s report noted that “the results seemed good” because they often heard the planes “turn violently” and saw some leave black smoke as they retreated, which proved some rounds reached their targets.

The first raid lasted 80 minutes. A second one started at 4.15am and lasted another 65 minutes. Throughout the night, the ship’s crew kept up the smokescreen and helped the townsfolk. Cowes and East Cowes, destined to be razed, still sustained heavy bombing along the river areas, but the death toll was reduced to 70.6

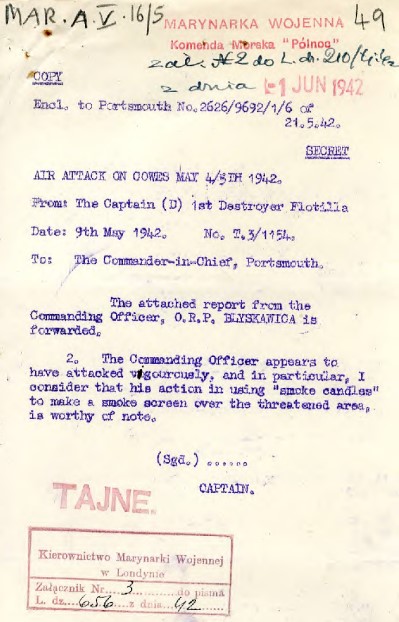

The Commander-in-Chief, Portsmouth forwarded Commander Francki’s report on the attack in Cowes and East Cowes on 4–5 May 1942 to the Secretary for the Admiralty and included this endorsement:

2. The Commanding Officer appears to have attacked vigorously, and in particular, I consider his action in using “smoke candles” to make a smoke screen over the threatened area, is worthy of note.7

Commander Francki, his crew, and his ship have become immortalised in Cowes. In 1982, 1992 and 2002, it erected memorial plaques to mark the anniversaries of the events of May 1942. In 2004, the commander’s daughter, Janina Doroszkowska, unveiled a plaque in memory of her father, who “of his own volition, ordered his ship to remain armed to defend Cowes in anticipation of an enemy attack.” It is at the entrance of of a public amenity area that was named Francki Place. In 2007, a sister plaque specifically commemorated the 70 victims.8

After the war, several of the seamen off the ORP Błyskawica settled in Cowes.

Wreath-laying at Francki Place, Cowes, on the 75th anniversary of the May 1942 blitz.9

_______________

While the ORP Błyskawica crew battled the Luftwaffe, Michał Pąk senior and his three older sons were in the USSR, ‘free’ but stranded. They were among the approximately 900,000 Polish civilians from eastern Poland who had been captured by Stalin’s NKVD,10 his Secret Police, and taken by cattle-trains to forced-labour facilities in northern Russia and Siberia, and kolkhozes in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan.

After Hitler’s troops moved across Soviet-occupied Poland and into Russia in June 1941, Stalin opened negotiations with Poland and ‘amnestied’11 the Poles so that they could form an army on Russian soil, ostensibly to help the Red Army repel the Germans who were then close to Moscow. The Poles, suddenly free to leave the forced-labour facilities, still had to travel thousands of kilometres south or west to get to this new Polish army in southern Russia.

General Władysław Anders, freed from his prison cell at the NKVD’s Lubyanka headquarters in Moscow, took control of the formation of the new Polish army. Conditions in southern Russia were so cold by the time the first Poles enlisted there, that he negotiated to move the enlistment stations south to Uzbekistan.

Although the Soviet call was for Polish men, they refused to leave their families behind. The knowledge that another winter was eminent made them strive to get away as quicky as possible, but outside the forced-labour facilities, the situation became even more dire. Some men regretted putting their wives and children in positions where there was no food, water, or paid work. Thousands died on the journey and those adults who survived were more a tangle of emaciated and ragged bodies than men or women fit for battle.

Michał Pąk realised he could not look after his sons, and put them into an orphanage near Tashkent, but when he saw them again, they were starving, sleeping on the ground in a freezing tent, and Jan close to death. He had by then found out enough information to enrol Henryk and Tadek into the Polish army’s cadet school, left seven-year-old Jan in the care of a friend, and enlisted, aged 45. He described himself as “a skeleton… of no use for other, harder tasks” and eventually joined the 5th Kresowa Infantry Division’s Field Hygiene organisation.12

_______________

The day before the ORP Błyskawica’s first brush with the Luftwaffe in Cowes, General Anders—appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Second Polish Corps—was in London with Polish President-in-Exile, General Władysław Sikorski, and other commanding officers to discuss Polish army formations in Scotland, the USSR, and the Middle East.

General Anders had been responsible for the escape of 43,808 Polish soldiers and their families from the USSR a few weeks earlier. He estimated through reports that around 1.5-million Poles in total had been removed from Poland into the USSR between 1939 and 1941, and this mere fraction of Poles that had reached the army enlistment stations worried him.13

The Poles crowded onto cargo vessels and fishing boats and crossed the Caspian Sea from Turkmenbashi (then Krasnovodsk) in Turkmenistan to Bandar Anzali (then Pahlevi) in Iran. General Anders was still negotiating the removal of more Polish soldiers and civilians from the USSR:

“There was no time for long explanations and arguments by telegram: either I could save the civilian population or leave it to its fate. Evacuation might mean that some would die in Persia, but if they stayed in Russia, they would soon all be dead.”14

The Pąks were among the 69,247 Poles who crossed the Caspian Sea—separately—in the 22 days before 1 September 1942. Few others managed to cross the border, and by January 1943, those Poles still alive in the USSR were declared Soviet citizens.

One of the tightly packed cargo ships that brought Polish soldiers and civilians across the Caspian Sea from the USSR to Iran in 1942.15

By September 1942, the Polish army formed in the USSR gathered at Quizil Ribat in Iraq. General Anders described his headquarters as:

“… several primitive little huts… surrounded by a sea of tents pitched on the sand of the desert… Our soldiers never grumbled about the [malaria] epidemics, the heat or the desert; they only grumbled about the slowness of the arrival of arms and equipment and the consequent delay in their training.”16

The first divisions of the Second Polish Corps arrived in Italy in December 1943, two weeks after the Teheran Conference in which Britain and the USA agreed to allow the Soviet Union to annex eastern Poland along the same lines as they had done with Hitler in September 1939.

By January 1944, the entire Second Polish Corps had moved to Egypt, then to Italy for what was to be the Poles’ pivotal role in the taking of Monte Cassino in May 1944 and the retreat of the Germans.

_______________

Whereas the residents of Cowes and East Cowes recognised and acknowledged the Polish crewmen from the ORP Błyskawica, the residents of mainland Great Britain who did not did witness Poles in battle, did not seem to share their appreciation. Mainland Britons could not have missed the publicity about the No. 303 Kościuszko Polish fighter squadron that shot down 60 German aircraft in the 1940 Battle of Britain—a tally that grew to 203 by the time the war ended.

Apparently for that, the organisers of the 1946 VE (Victory in Europe) celebrations in London invited 25 Polish airmen to participate in the parade. They declined once they realised that the organisers had snubbed the Polish army—soldiers responsible for victories in several pivotal battles in Italy, France, Belgium, the Netherlands and Germany—and also snubbed the Polish navy that played its own part alongside the British navy in defending the north Atlantic and Baltic seas from prowling German U-boats, and Britain itself. Instead, the VE organisers invited Soviet-controlled Poland to send a contingent. It also refused.

_______________

Wojciech Francki, his wife, Irena née Siedlecka, and their children Richard (17), Maciej (12), and Janina (8), arrived in Wellington in December 1948. They were among six Poles of the Akaroa’s 195 mostly English passengers. The others were pilot Kazimierz Borowski, and his wife, Mildred. Wojciech was listed as a naval officer. The New Zealand government had given them their permanent residency permits the previous May.

Michał Pąk did not have it quite as easy getting accepted by New Zealand. Perhaps it was his lower status as a soldier, but the New Zealand authorities at first denied his application to allow him, Henryk, and Tadek to join Jan, who had arrived with 732 other children and their 105 caregivers in November 1944, and who had been settled in Pahiatua. Michał and his sons were then granted a visa for a year, and they arrived in Auckland from Liverpool a month after the Franckis. By November, the New Zealand government had granted permanent residency to all three, and to Zofia, who was still in Poland.

It is not clear when the career veteran Wojciech Francki and the volunteer veteran Michał Pąk met, but before WW2, they both lived in the same area in northeastern Poland: Wojciech had made his home in Wilno. Michał farmed about 200 kilometres farther east, and when Germany invaded Poland in 1939, he and others from his village went to Wilno to enlist. There is no doubt that both men would have considered themselves lucky to have survived the war, and to have had their wives and children survive too.

Not that all had gone their way:

Much as the Wojciech Francki longed to return to his homeland, he knew that under the post-war Moscow-controlled regime, his fate would have followed the same trajectory as that of those with whom he graduated from naval college: He told Teresa Dobrzyńska-Mordes in a 1989 interview at his Sydney home that most of his naval college classmates who returned to Poland after the war had been executed.17 He spoke of his love for his country, his early career, the ships he commanded, his time after WW2, his 60th wedding anniversary, and his children. Not once did he mention the battles at Cowes, or his slew of war medals.

The Franckis had apparently wanted to go to Australia, but that country then accepted only Polish airmen and soldiers who had fought in Tobruk, and so-called displaced persons (DPs) from Germany and England.

Although the New Zealand government seemed to present a positive third choice of post WW2 home for the Franckis, and Wojciech had apparently been offered a good job, once they arrived, he was informed that he was not allowed to pursue his naval career, or work on ships. His only options to earn a living were narrowed to labouring. In New Zealand, he worked for a year in a quarry, then as a gardener at an Auckland convent school, and privately. Irena worked as a seamstress and the children all received tertiary education.

_______________

Like Michał Pąk, Wojciech Francki had fought in the 1919–1920 Polish-Soviet War. On 18 March 1921, Poland, Soviet Russia, and Soviet Ukraine signed the Treaty of Riga and ratified the Polish-Soviet boundary. Earlier, the Treaty of Versailles granted Poland a new independent state after WW1 ended 146 years of partial and then total partitioning by its neighbours Prussia, Russia, and Austria. The signatories of that treaty, however, declined to define the new state’s borders, which left the Polish-Bolshevik/Soviet tensions unresolved.

After the Polish-Soviet war, Michał Pąk became one of the thousands of “military settlers” who turned pieces of raw land in the east of the geographically resurrected Poland into productive farms. Wojciech Francki, his junior by six years, finished his studies in 1927 and pursued his love of the sea.

Wojciech had left Poland two months before WW2 began, to command the cadet training ship ORP Wilja. The ship made a scheduled stop in Greece, had gone through the Strait of Gibraltar, and was docked in Casablanca on 1 September 1939, when the ship’s doctor, who had been listening to the radio, told him, “Well, it has begun.”

Commander Francki opened his sealed orders. They instructed him to report to the nearest British authority, which happened to be a newly arrived British cruiser. Its captain told the Pole that he and his crew should “be patient” while they waited to be transported to England as spare crew for other Polish battleships leaving Poland.

“We waited almost six weeks for this transport,” the commander said in the 1989 interview. He may have used this down time to arrange his family’s escape to Scotland, because Irena and their children—Janina as a new-born—left Wilno in January 1940.

While Michał Pąk and his sons remained in northern Russia, and his wife evaded the Soviets occupying Poland, the British Admiralty appointed Commander Francki to the ORP Burza (Storm), which took part in the May 1940 evacuation of nearly 200,000 soldiers of the British Expeditionary Force and more than 100,000 French and Belgian soldiers from the beaches of Dunkirk.

Mrs Cecylia Raczyńska, wife of the Polish ambassador to Britain, Count Edward Raczyński, launched the ORP Błyskawica on 1 October 1936. Wojciech Francki joined its list of commanders in 1942, one of those who served several times, the last in 1946.

A few weeks after Irena Francki and her children left Soviet-occupied Poland, Zofia Pąk and her toddler son were left behind. In the early hours of 10 February 1940, Soviet soldiers banged on the farmhouse door, pushed their way inside, and took Michał and his three sons, then aged 13 to seven, to the NKVD forced-labour facility at Diabrino, northern Russia. Zofia, and Michał junior happened not to be home that night. For the next 16 years, Zofia and Michał junior were nomads in their own country. After the war, family took in Michał so that he could go to school, but Zofia felt it was not safe to stay with him, and moved regularly.

Michał senior and his sons barely made it out of the USSR. Wojciech knew well how lucky he had been to see his family during vacations from ships:

“I saved my family. I did not suffer in the war myself, and yet thousands of people found themselves in much worse situations than I did. I could complain about this or that, but I was never hungry, and I did not walk without shoes. I raised my children, and I remained a Pole.”

Michał Pąk junior’s wife, Zenona, arrived in New Zealand with her parents and brother in 1950. She remembered Wojciech Francki well:

“Commander Francki helped a lot of the Polish people settle in, helped them with documents, advised them. He was a person who everyone looked up to. He would help you with all legal matters, and steer you to where you need to go to get help. For years he was a gardener, and yet he was such an educated man. He never looked down on you. He was amazing to so many of us.”19

_______________

One cannot imagine what it must have been like for a naval commander with such a distinguished record to be land-bound for 18 years.

It is not clear why Wojciech and Irena Francki remained in New Zealand for so long, especially as their children left six and seven years before them: Their son Maciej qualified as a civil engineer, then left for Sydney on the SS Orsova in May 1960. Richard, his wife, Zofia (née Surynt) and their two infant children left on the TSMV Wanganelia in April 1961, also bound for Sydney. Once Janina qualified as a teacher, she left for England in December 1961, and married Andrzej Doroszkowski a few years later.

“Mr & Mrs Francki” sailed on the TSMV Oriental Queen from Auckland on 9 January 1967, bound for Sydney, to live with one of their sons and his family.

The Australians allowed Wojciech to be a sailor.

“I went to the merchant navy for a job. I was approaching 63, and according to Australian regulations, I could only work for a year, but they helped me get a job on foreign ships. Until I was 76, I sailed on Swedish, Norwegian, and American ships. Then the insurance companies forbade me to work.”

In the 1970s, when he worked on a Swedish trade ship that docked in Rotterdam, he took leave, went to the Polish embassy in The Hague, and requested permission to visit Poland. Despite his Polish citizenship, he was refused, told that it “would be different” if he had an Australian passport.

He remained a reluctant exile and never took on another citizenship, which always complicated coming home to Irena as he had to apply for permission to return to his country of residence.

He did eventually get his wish to return to his Poland. After he died in Sydney in 1996, his ashes were brought to the family gravesite at the Powązki Cemetery in Warsaw. He joined his parents and his siblings, and Irena’s ashes joined his in 1999.

Richard and Maciej Francki remained in Australia and died there.

Michał Pąk senior died in 1981. Before his wife and son arrived in 1956, he had bought four acres in Glen Eden and set it up with ducks, chickens, bees, and a cow, Gizela. Zofia started making cottage cheese and cream, and settled into her husband’s life in Auckland. She died in 1987, and is buried close to her husband at the Waikumete cemetery. Henryk died in 2012, Tadek in 2018 and Jan in 2014. Michał junior still lives in Auckland.

_______________

On the 70th anniversary of the May 1942 blitz, Commander Francki’s daughter Janina Doroszkowska laid flowers at the memorial headstone in East Cowes- Kingston cemetery which represents many of the 70 victims.20

This year’s Cowes commemoration of the 4–5 May 1942 Blitz, and the ORP Błyskawica’s role will be without the presence of Janina née Francki Doroszkowska, who died in 2020.

In a 2018 interview with Belgian historian Maître Pangloss, Janina recalled how the family felt after the Polish naval detachment to Britain was formally abolished on 24 September 1946:

“We were all devastated that we had seemingly won the war but lost our country. It was a black time indeed. The worst day of all was the day father had to hand over ‘his’ beloved ORP Błyskawica to the Royal Navy who he knew would then hand her on to the Communist government in Poland. The grief of my parents, the poignancy and the completely funereal atmosphere of that day will stay with me as the worst day of my life.”

A year after her father’s death, Janina became a founding member of the Friends of the ORP Błyskawica Society. Her daughter, concert pianist Eva Maria Doroszkowska, will carry on the family tradition of attending the commemorations and again give a piano recital in honour of her grandfather, his crew, and one of Poland’s most famous warships.

The ORP Błyskawica returned to Poland in 1947, and is now a museum ship in Gdynia.

© Barbara Scrivens, 2022.

ENDNOTES:

- 1 - Although Woiciech Francki obviously held lower positions during his naval career, for the sake of clarity, I have used this last one throughout.

- 2 - Events listed on the Friends of the ORP Błyskawica Society’s News page:

https://www.blyskawica-cowes.org.uk/news/ - 3 - From the Polish Institute & Sikorski Museum’s naval archives, page 33, in English:

https://pism.org.uk/img/archiwum/dokumenty/MAR/MAR_A_R5_16/MAR_A_R5_16_05.pdf - 4 - Ibid PISM, page 32. The full report in Polish is on pages 31–32.

- 5 - The English version is available from the Friends of the ORP Błyskawica Society:

https://www.blyskawica-cowes.org.uk/cowes_attack/ - 6 - For a more detailed report on the Cowes Blitz, see the Friends of the ORP Błyskawica Society

website page:

https://www.blyskawica-cowes.org.uk/

Another version is available at:

https://www.h2g2.com/entry/A87759229 - 7 - Ibid PISM, page 52.

- 8 - All the plaques can be seen on The Isle of Wight’s Memorials and Monuments page:

http://www.isle-of-wight-memorials.org.uk/others/cowesblitz1942.htm - 9 - Photograph from Friends of ORP Błyskawica Sociey:

https://www.blyskawica-cowes.org.uk/anniversary_75/ - 10 - Narodny Kommisariat Vnutrennikh Del, or the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs.

- 11 - The word ‘amnestied’ is in single quotation marks because it is a farcical way to describe people who had done nothing to deserve their imprisonment in the USSR, and therefore had no need for any kind of so-called ‘amnesty.’

- 12 - For more on the Pąk story, see:

https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/michal-pak-zenona-cyckoma-pak/ - 13 - Anders, Lt-General W, CB, An Army in Exile, Chapter 12, Those We Left Behind, pages 116–121, originally published in 1949. Reprinted by The Battery Press, Nashville, ISBN: 0-89839-043-5.

- 14 - Ibid, page 102.

- 15 - This photograph from the Kresy Family Polish WWII History Group’s page Evacuation to Persia:

https://www.kresyfamily.com/7-evacuation-1.html. - 16 - Anders, ibid, page 131.

- 17 - Thanks to Auckland historian Jacek Drecki for sharing a copy of the interview. The newspaper cutting is

incomplete, faded in places, and in Polish. The headline says Z wizyta u ostatniego dowódcy ORP „Błyskawica” komandora

Wojciecha Franckiego: Wszystko przeszło, przeminęło z wiatrem… (A visit to the last commander of the ORP

Błyskawica, Commander Wojciech Francki: Everything passed, passed by like the wind.)

It is not clear in what publication the interview appeared, and attempts to find out more about the author have so far proved fruitless. - 18 - Ibid 1989 interview.

- 19 - Ibid the Pąk story on the page above (citation no. 12)

- 20 - Photograph from https://www.blyskawica-cowes.org.uk/anniversary_70/

- 21 - The full story on:

https://wartimelondon.wordpress.com/2018/12/12/new-cavendish-street-and-the-free-polish-navy/