THE LANGUAGE OF CHILDREN

– ALLAN HUGHES, JAN JARKA, AND THE BOND THAT REMAINED

by Barbara Scrivens

Making lasting connections with a stranger from the other side of the world was the last thing on 12-year-old Allan Hughes’ mind as he watched two trains filled with Polish refugees pull into Palmerston North on 1 November 1944.

The crowd at Palmerston North as the trains slowed through the city.1

It took nearly 60 years and the marriage of their children for Allan and Jan Jarka, one of the boys on the trains, to re-connect in Auckland.

In the final years of World War 2, the boys’ experiences could not have been more dissimilar. Allan had led what he called “a sheltered life” in New Zealand. Jan, aged 14, carried memories of being forcibly taken from his home in eastern Poland by the Soviet secret police (NKVD), the deprivation of an NKVD kolkhoz in the USSR, and the loss of his parents.

Like Jan, many of the more than 700 Polish children on the two trains were orphans. Some had family members in the Polish army, air force and navy in Europe and the Middle East.

To the New Zealanders they looked different and they spoke differently. For the Poles, the warm reception they received from Palmerston North’s residents stood out as very different from any they had experienced since Hitler invaded Poland from the west on 1 September 1939 and Stalin from the east on 17 September.

Five years later Polish boys with their recently shaved heads and and over-sized army-styled clothing, and quiet Polish girls with neatly tied-up hair—or if shaved, hidden under a beret—looked out of the sash windows as the carriages slowed on approaching the Palmerston North Railway Station. (The railway station in the central city was moved in 1964, but the tracks remain in what is now a park.) The trains had left the Wellington dock a few hours earlier. By the time they arrived in Palmerston North engine water and coal needed replenishing before they could continue through the Manawatu Gorge and on to their destination, the Pahiatua Railway Station.

Photographer John Pascoe, who travelled with the Polish contingent, took this image, and the one above, from the train. Allan's mother, Flora Hughes, is in the right foreground with the decorated hat and behind the woman with the plain hat, glasses and stole.2

__________

Allan and his group of school friends and neighbours waited to meet the war-ravaged children they had been hearing about:

“We knew these people couldn’t speak English and we couldn’t speak Polish so how do you communicate? It was a bit awkward in the beginning but that broke down after a very short space of time. These kids couldn’t believe the sheer volume of stuff being given to them—chocolates and lollies and books and toys and writing gear and comics—people just brought what they could and as things began to run out, they went back to their homes to get more.”

A manawatu evening standard story the next day said:

Long before the first train was due to arrive the crowd was so dense on the station that there was little more than standing room and welcoming crowds also flanked the railway line through the Square. On the platform the Girl Guides, holding red and white streamers, formed the Polish flag, above which was the word “Witajcie” (Welcome), while colour parties of Guides and Boy Scouts stood at the back holding the Guide International Flag and the Polish and New Zealand flags.

A tumultuous shouting from the New Zealand children greeted the first train as it drew into the station, and the Guides surged forward to present the visitors with apples, sweets and floral posies.3

Judging by the way the Polish children are facing out of the carriages, and the Girl Guide uniform, this photograph is likely to have been taken during the Palmerston North stop. The two boys were identified as Józef Sokalski and Rudolf Szymczycha.4

Local adults included officials from organisations such as the Red Cross, the Polish Army League, and various schools and organisations in the area.

The Polish children and their caregivers were in New Zealand at the invitation of the New Zealand government. They had been in limbo in Persia for up to two years as their country remained in the grip of war, her soldiers, air and sea personnel still fighting the Germans.

A year earlier Prime Minister Peter Fraser saw the plight of a similar group of Polish refugees who stopped overnight in Wellington harbour on their way to Mexico. He decided that New Zealand could—and should—extend the same kind of hospitality. The Polish government-in-exile in London and the New Zealand delegate to the Polish Ministry of Social Welfare, Countess Maria Wodzicka, immediately started making arrangements for New Zealand to host its own Polish refugees.

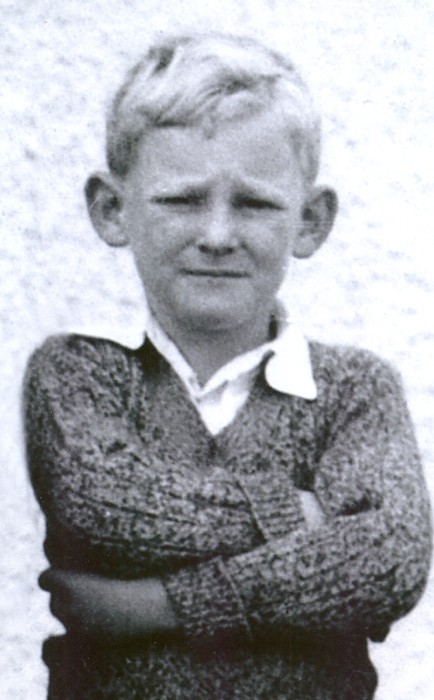

In 1944 Allan, pictured here in 1941 as a pupil at West End School, remembers how the initial hesitation from the Polish children evaporated as they realised the arms full of chocolates, sweets, books, and toys were gifts for them.

“The call had gone out that there was a trainload of Polish children coming though Palmerston North to go to Pahiatua and that it would be stopping for a while. We could have a day off school to meet the train and pick up whatever we could spare to give to them. It was wartime and things like chocolate and lollies were in short supply because sugar was rationed.

“They were supposed to stop for 20 minutes. They stopped for nearly two hours. The trains started to go several times but the local people beseeched the drivers find some reason to stay, to hold the train up a bit longer because an auntie had gone home to get some toys for the children or an uncle had got on his bike and gone to the fish and chip shop to bring back something.”

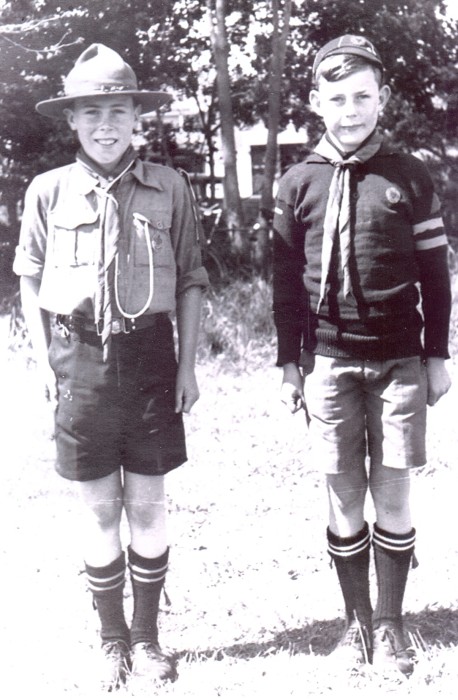

The Polish and New Zealand children differed in their spoken words—but found other ways to communicate. Arnie Rule, pictured here on the left with his brother Eddie, wore the same scout uniform as he walked along the train collecting autographs, one of them from Jadwiga Jarka, Jan’s older sister.

“I climbed aboard with my autograph book and a pen and with a sign language asked them to write in it. They knew exactly what I wanted them to do.

“Language—you find a way around it. That’s what kids do.”5

Arnie still remembers the sense of joy and fun in the air that day.

_______________

Allan: “The train visit was an event for the town. The Polish refugees were like celebrities.”

“We hadn’t seen people from another country for quite a few years because there was no travel for private people outside the country’s borders, and you even needed a permit to travel inside New Zealand. My brother in Whanganui had to go to the government to get a civilian travel permit to ride on a train.

“You couldn’t change your job without going through the government. Before you could leave one job and go to another, you had to go to the Land Power Office and get official permission, and they would tell you where to work next. Even if you had a job to go to they could say, no, you had to go into the freezing works [because] we need food, or you had to go to some Watties processing cannery in Hawke’s Bay.”

Allan believes the deluge of gifts stemmed in part from a sense of patriotism the local people felt towards the children of one of New Zealand’s allies. Families with men who were fighting, or who were prisoners of war, like Allan’s older brother, Lloyd, had another reason—Polish civilians had a reputation for helping escaped prisoners.

Perhaps the sudden close contact led to understanding and sympathy?

“The first thing that we thought of when we saw the children was how strange they all looked because they had shaven heads and in New Zealand nobody had shaven heads, so even if any of them had got off the train they would have been very easily recognisable.”

Allan did not know then that the head-shaving helped control lice and diseases that the refugees had come into contact with in the USSR. Their normal hygiene in Poland suffered in the primitive cattle wagons the Soviets used as human transport, and in the rough-hewn timber huts in the forced-labour facilities. Staying clean and disease-free became almost impossible in kolkhozes in Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan where Poles—finally allowed to leave their NKVD captors to join the Polish army—were abandoned in 1941 and 1942 with no food or water and only the most rudimentary shelter.

In June 1941 Germany invaded first Soviet-occupied Poland, then Russia. As his new enemy gathered strength, Stalin decided to use the able-bodied Poles already in the USSR to augment his Red army. He agreed to a Polish army being formed on Russian soil and granted ‘amnesty’ to Poles in his territory.

During the latter part of 1941 and in 1942 all the Polish refugees on the trains in Palmerston North had made journeys to the Polish army’s enlistment camps first set up in southern Russia then in Uzbekistan. Those who heard of the ‘amnesty’ were ‘free’ to join the army but they had to travel sometimes thousands of kilometres to get there.

Enlistment into the Polish army in 1941 and 1942 carried few rules. The able signed up, and were usually accepted.

As more Poles made their way towards the enlistment camps in southern Russia, Polish officials gathered orphaned and abandoned children. Bronisław Bojanowski recalled how he and his father made the decision to leave his younger brother, Władysław, outside an orphanage in Uzbekistan with a piece of wood on which they had written his name and explaining that he was alone. Bronisław and his father, on their way to enlist, had tried to get Władisław into the orphanage officially but were told he was too old. He was 15 that day in Palmerston North. (See Bronisław's story, faith, self-belief, courage.)

Enlistment into the Polish army in 1941 and 1942 followed few rules. The able signed up, and were usually accepted. As long as there was one member of a family in the army, the rest came under its auspices. The Poles had been granted ‘amnesty’ but as long as they remained in the USSR they remained at the mercy of Soviet authorities. Hundreds of thousands did not make it out.

Between 23 March and 5 April 1942 more than 43,000 Polish troops and civilians were processed through Pahlevi, and between 10 August and 2 September the same year 69,000 more landed there. Finding enough civilian clothing became challenging—hence the over-sized military outfits for the boys.

In Pahlevi the Poles went through disinfection, their ragged clothing discarded and exchanged. Joe Jagiełło, aged eight when he arrived in New Zealand, remembers looking with interest at the lice and larva crawling over his old clothes on the floor as he went through the decontamination process. (See Joe's story, from siberia to safety.) Another of the younger Pahiatua orphans, Franciszek Szeptner, later told Jan’s son, Michael, that he wore army shirts and shorts with the sleeves and trouser or shorts legs rolled up several times.

As Polish army personnel moved towards military training camps and action in Europe and the Middle East, Polish civilians moved inland from Pahlevi to other camps in Teheran (Tehran) where mothers with children stayed until they were allocated to family refugee camps in places such as eastern and southern Africa, India, Argentina and Mexico. Isfahan (Esfahan), about 450 kilometres south of Teheran, accommodated a growing number of Polish orphanages.

[T]hey were already imprisoned in the USSR by the time Hitler pushed the occupying Russians out of their part of Poland in June 1941.

Mothers accompanied some of the children but not all the adult caregivers were parents. There was a priest, three nuns, a doctor, a dentist and eight other personnel who had worked with the children under the Isfahan health service. Other caregivers who had held positions in Isfahan included at least 30 teachers, 25 domestic and administration staff and 20 “House Mistresses” or “House Masters.”6

Judging from newspaper articles on 1 and 2 November 1944 New Zealanders seemed unaware that Poland had two enemies—Russia and Germany.

Under a sub-heading HORRORS OF NAZI RULE, the manawatu evening standard said some of the refugees were from “peasant stock” and others from “cities like Warsaw.”7

The sub-heading had little to do with the Polish refugees in New Zealand. They came from eastern Poland and, yes, might be considered “peasants”—if that meaning included comfortably well-off owners of small farms. But they were already imprisoned in the USSR by the time Hitler pushed the occupying Russians out of their part of Poland in June 1941. Those particular Polish refugees in New Zealand experienced Soviet—not Nazi—horror.

One can understand the newspapers’ misrepresentation of reality: Churchill and Roosevelt by then considered Stalin a useful ally and few outside war cabinet rooms knew of the secret accords agreed to between Britain, America and Russia that sealed Poland’s fate after the war.

Allan: “We had a certain amount of news about the war but we also knew everything was censored and the government only allowed the printing of news that was favourable to the Allies. We never got all the details.”

__________

The manawatu evening standard, like other New Zealand newspapers, was apparently fed the incorrect information regarding the Poles’ capture, incarceration in the USSR, and their escape. In its 1 November 1944 issue, the newspaper was accurate in describing the group as:8

… a party of 838 Polish children and adults who have at last found a haven after enduring unimaginable hardships.

It was wrong in saying that after the outbreak of the war:

… They had to flee from their homes and for their lives. They moved to Siberia and other parts of Russia.

The Polish refugees in New Zealand did not flee from their homes. They were forcibly removed and transported out of their country against their will.

The newspaper was again correct in saying:

Parents died of starvation or disease and many children died, too. It was the survival of the fittest in the grimmest sense of the words.

It was less accurate in the description:

During their homeless and almost ceaseless wanderings, parents and children became separated beyond hope of reunion.

Far from “ceaseless wanderings,” the Poles knew their intended destination—the Polish army’s enlistment camps. They also knew Soviet trains were the best form of transport, but Soviet soldiers then filled most of those trains. Separations of Polish relatives occurred from the deliberate habit of Russian trains departing without warning from stations after Poles disembarked to look for food and water, or from family members going into hospital, or into orphanages. Family members joining the Polish army created the bulk of later separations.

__________

The Polish children left Palmerston North smiling, still hanging out of the windows, and waving goodbye to people no longer strangers. Allan went back to his house on Main Street, next to the railway line, and Jan Jarka continued to the Pahiatua camp with Jadwiga. Little did either boy know that they would become family one day when Jan’s son, Michael, married Allan’s daughter, June.

Did Allan and Jan meet that day in 1944? Allan believes it would have been impossible not to have exchanged something—a smile or a gift—with a boy almost the same age, because he and the other local children walked up and down the carriages several times.

Their children introduced Allan and Jan formally in 2003 when they arranged a meeting of future parents-in-law.

“I can’t remember exactly what we said but there is always an interrogation of a prospective son-in-law and I wanted to know what the families may have in common. Of course I questioned June about Michael’s surname and when I heard his father was one of the Pahiatua ‘children’ I told the family ‘I’ve met this man before but he doesn’t know it.’”

Michael and June married in 2004 when Jan was 74 and Allan 72. Jan died in 2008.

Allan still has an ear for a Polish surname or accent.

“I’ve always found that if I run into any of those Polish people and say I’m from Palmerston North, and was at the railway station that day, their smiles are immediate.”

__________

Photographs of the children’s arrival show the ease with which they interacted with New Zealand army personnel helping with their transport and at the camp. From the Pahiatua railway station, right,9 the refugees climbed on to army trucks, below,10 and driven the last two kilometres to their new home.

Pahiatua's new refugee camp had previously been used to intern about 180 “enemy aliens.” They included resident Germans, Italians and Japanese who returned to their original quarters on Wellington's Soames Island after authorities identified Pahiatua as best place to temporarily house more than 800 people. Before the New Zealand government took it over in 1942 the camp grounds were home to the local racecourse.11

Material for extra dormitories and classrooms was salvaged from buildings in military camps around New Zealand that had previously housed American Marines and RNZ Air Force personnel.

Contractors started the work 10 weeks before the Poles’ arrival. “Hutments” accommodated teachers, the priest, medical staff and other administrators. The classrooms caught “the maximum amount of sun” and the cheerful hospital had 24 beds. Jan and Jadwiga Jarka were placed into separate girls’ and boys’ dormitories that housed 90 children and six adults each.

Some of the youngest boys in one of the dormitories. The children's few possessions barely filled one drawer.12

In preparation for their guests, the Prime Minister had called a meeting to form a Polish Children’s Hospitality Committee and, together with Pahiatua mayor SW Judd and camp commandant Major Foxley, organised local committees. The Sunday before the Poles arrived, more than 100 local women, travelling on the same army trucks, made the beds and brightened the dormitories with flowers, curtains, and toys.

The New Zealand hosts seemed to have thought of everything—except the Polish interpretation of the watchtowers, barbed-wire fencing and gates constructed for the camp’s prior occupants.

It did not occur to the always-free New Zealanders that to the recently incarcerated Poles the sight of similar towers and barbed-wire immediately brought back a shocking reminder of Soviet cruelty. Had they travelled half-way across the world to be jailed again?

The misunderstanding was soon rectified.

The hospitality and generosity of the people of Palmerston North and its surrounding districts continued at the Pahiatua camp. New Zealand Army personnel and several WAACs (Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps) remained on the camp staff to augment the Polish adults.

The manawatu evening standard described the Poles’ first evening meal on New Zealand soil as:13

… hot roast beef with mashed potatoes and silver beet and creamed rice as the second course.

This photograph is described as: “Small boys eating a meal at Polish children's refugee camp, Pahiatua.”14

_______________

In 1941 the Department of Statistics estimated 1,740 people lived in the borough of Pahiatua and a further 3,250 in the surrounding administrative county. New Zealand then had 72 boroughs and counties in the North Island and Pahiatua represented the 53rd largest (or 19th smallest) borough.15

The provincial town coped gracefully with its injection of 838 extra people in 1944. Even though the camp has returned to pasture and all that remains is a stark memorial, Pahiatua still commemorates the children it nurtured during the last years of the war—and afterwards.

As I drove through the town in April 2015 I noticed a Polish flag outside a café and stopped. Could the owner be Polish? No, but her cafe had taken part in the 70th anniversary of the children’s arrival. She seemed not to notice the fluttering white and red.

It had become part of the main road’s landscape.

© Barbara Scrivens, 2015

Updated March 2019

FOOTNOTE: Allan Hughes died in January 2019.

June Hughes Jarka: “He is remembered as a bridge between two cultures.”

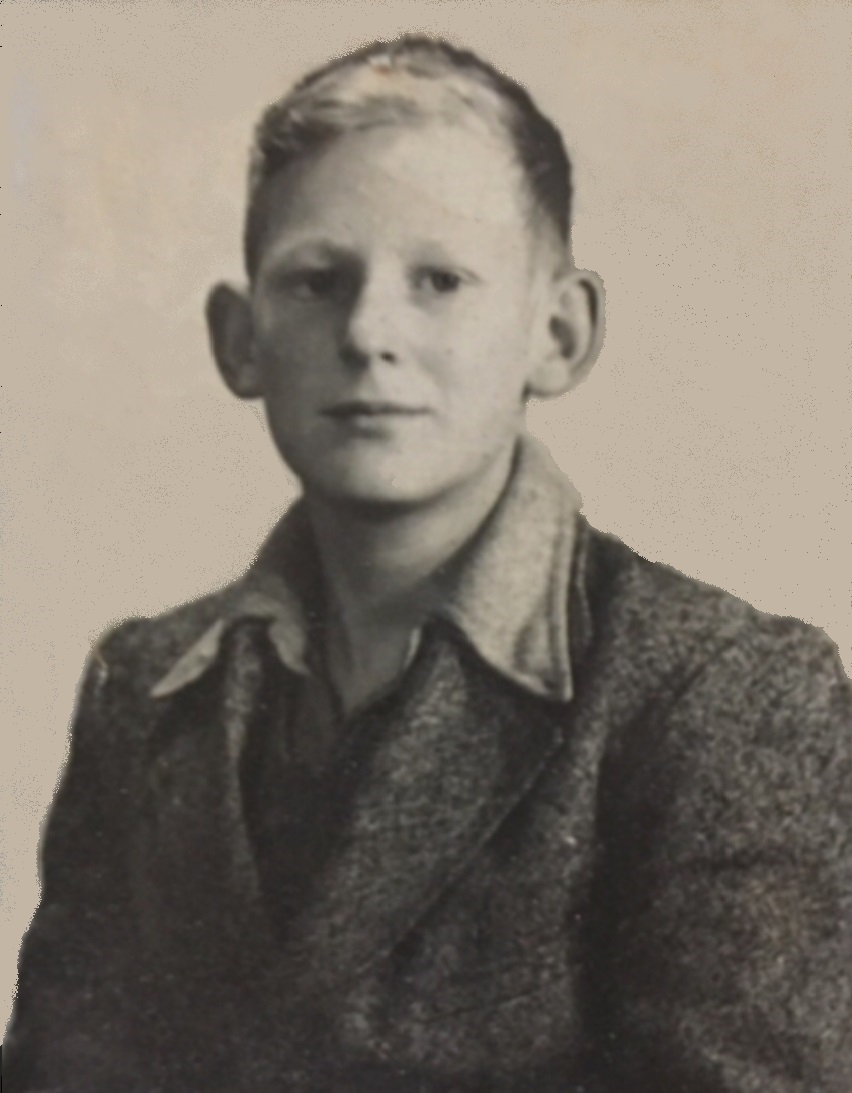

Below are photographs of Jan (left) and Allan as teenagers, Jan in Pahiatua before he moved to Auckland in 1949.

UNLESS OTHERWISE STATED, ALL PHOTOGRAPHS FROM THE JARKA-HUGHES AND RULE FAMILY COLLECTIONS.

ENDNOTES:

- 1 - Pascoe, John Dobree, 1908-1972: Photographic albums, prints and negatives.

Crowd greeting Polish refugees on their train journey to Pahiatua from Wellington. Alexander Turnbull Library,

Wellington, New Zealand, Ref: 1/2-003644-F.

http://natlib.govt.nz/records/32058568. - 2 - Pascoe, John Dobree, 1908-1972: Photographic albums, prints and negatives. Crowd standing next

to railway track in The Square, Palmerston North, to greet Polish refugees enroute to Pahiatua. Ref: 1/2-003645-F.

http://natlib.govt.nz/records/32195254. - 3 - Manawatu Evening Standard, 2 November 1944, WARM WELCOME, POLISH CHILDREN GREETED, copy available on microfiche through the Palmerston North City Library.

- 4 - Pascoe, John Dobree, 1908-1972: Photographic albums, prints and negatives. Polish refugee

children being greeted by New Zealand children, location unidentified. Ref: 1/2-003649-F. Alexander Turnbull Library,

Wellington, New Zealand.

http://natlib.govt.nz/records/32195263. - 5 - Thanks to Arnie Rule for donating the photographs of him and his brother and of Allan Hughes.

Arnie donated his autograph book to the Polish Heritage Trust Museum in Howick, Auckland. We were not allowed to photograph the book and have been told that the museum has not digitised its collection. - 6 - Isfahan: City of Polish Children, was published by the Association of Former Pupils of Polish Schools, Isfahan and Lebanon in 1989. Third edition in English, ISBN: 0 95512550 1 2.

- 7 - Manawatu Evening Standard, 1 November 1944, page 4, POLISH CHILDREN, ASYLUM IN DOMINION, FROM WAR-TORN EUROPE, available on microfiche through the Palmerston North City Library.

- 8 - Ibid. All four of the following extracts come from the same article.

- 9 - Pascoe, John Dobree, 1908-1972, Photographic albums, prints and negatives. Polish refugee

children arriving at Pahiatua Railway Station. Ref: 1/2-003646-F. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New

Zealand.

http://natlib.govt.nz/records/32195274. - 10 - Pascoe, John Dobree, 1908-1972, Photographic albums, prints and negatives. Polish refugee children

enroute to camps at Pahiatua. Ref: 1/2-003654-F. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

http://natlib.govt.nz/records/32195277. - 11 - Information on the former prisoners at Pahiatua from:

http://www.oocities.org/somesprisonersnz/chronologyww2.html. - 12 - Pascoe, John Dobree, 1908-1972, Photographic albums, prints and negatives. Boys' dormitory at Polish

children's refugee camp, Pahiatua. Ref: 1/2-003663-F. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

http://natlib.govt.nz/records/32195340. - 13 - Manawatu Evening Standard, 2 November 1944, WARM WELCOME, JOY ON REACHING CAMP, available on microfiche through the Palmerston North City Library.

- 14 - Pascoe, John Dobree, 1908-1972, Photographic albums, prints and negatives. Small boys eating a meal

at Polish children's refugee camp, Pahiatua, Ref: 1/2-003665-F. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New

Zealand.

http://natlib.govt.nz/records/32195524. - 15 - From Statistics New Zealand's digital yearbook collection:

https://www3.stats.govt.nz/New_Zealand_Official_Yearbooks/1945/NZOYB_1945.html.