Joe Jagiełło

FROM SIBERIA TO SAFETY

by Barbara Scrivens

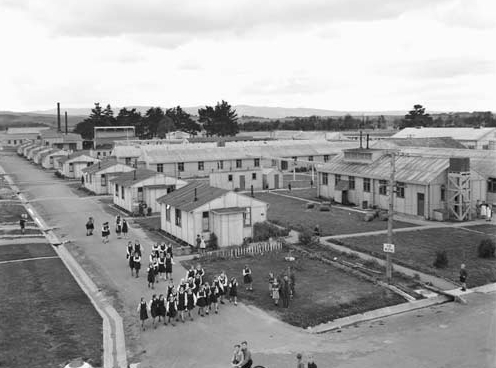

The last things Polish refugees expected in New Zealand in 1944 were the first things they saw as they approached the camp that their New Zealand hosts prepared for them in Pahiatua.

Watchtowers, barbed wire, gates and soldiers brought back raw memories of their recent incarceration in Soviet forced-labour facilities. The joy of the unexpectedly warm welcome along the route from Wellington to Pahiatua that day vanished.

New Zealand soldiers, helping the 733 Polish children and their 105 caregivers off the army trucks, soon realised something was wrong.

Then eight years old, orphan Józef (Joe) Jagiełło, remembered “a bit of a commotion.”

“The camp was built for Japanese prisoners of war. It still had barbed wire and watchtowers and we had to go through this gate, all guarded. There were soldiers everywhere. They didn’t have guns but it was like a prison.”

The Polish adults protested. Their anticipated respite from the rest of the Second World War evaporated. The boys, judging from the army fatigue caps they wore in this photograph, had already bonded with some of the New Zealand soldiers.1

“They quietened everybody down and explained that they hadn’t had time to pull the fences down because it was only a few weeks before that they shifted the Japanese out to the Featherston prisoner of war camp. They promised us they wouldn’t close the gate, that they would pull the whole fence down.”

From the casual way the evening post described the “high fences and sentry towers” in the camp the day before, it is clear the Poles’ horrified reaction was unexpected.

The story described the fences and towers as “reminders of the days when khaki-clad guards kept watch over German, Italian and Japanese prisoners” and of Public Works engineers being “justifiably proud” of the transformation of the camp, pictured below,2 into one able to accommodate four times as many people—and child-friendly.

The incongruity of the article’s title, nation's guests, polish children at home at pahiatua, and the nonchalant mention of the fear-provoking boundary, showed New Zealanders had little understanding of where the Polish refugees had been or what they had experienced.3

An article in the same newspaper months earlier quoted New Zealand Prime Minister Peter Fraser telling the House of Representatives that the children had “escaped to Russia and wandered about in all kind of weather without sufficient shelter or food and thousands of them died.”4

The children had not “escaped” to Russia. Soviet soldiers forcibly removed them and their families from their homes in eastern Poland in 1940 and 1941, locked them into dark and airless animal freight containers and transported them all over the USSR to NKVD-run forced-labour facilities. (The railway transports are described in further detail in missing humanity.)

On 10 February 1940, Soviet soldiers rounded up Joe, his parents, Franciszek and Maria, his grandmother, and 19 other families from Dobrzenica and transported them more than 6,500 kilometres to Gribanowa, near Alzamaj, west of Lake Baikal in southern Siberia.

Joe has two clear memories of that journey: They were not allowed off the train until they arrived at their destination weeks later; they received bread and water “if they were lucky” once a day.

Franciszek and Maria (née Sorzynka, pictured here) worked in the Gribanowa forest. Joe seldom saw them and it took a while for him to link his mother’s continued absence with the realisation that he would never see her again.

Months later Joe could not wake his grandmother—his sleeping companion. Adults told him she had “gone to heaven.”

After Hitler turned on Stalin and granted the Poles ‘amnesty,’ Joe and his father left Gribanowa. They parted in 1942 when Franciszek joined the Polish army in Uzbekistan. Joe moved into an orphanage.

Joe left the USSR—with other civilians under the auspices of the Polish army—by cargo ship across the Caspian Sea from Krasnovodsk to Pahlevi in then Persia.

On the left is a photograph of Joe with a woman he called “Aunty” who was his aunt Katarzyna’s sister-in-law. It was taken outside the Teheran hospital where Joe stayed for several months while recovering from an eye infection. “Aunty” used to write to Joe's father and read out Franciszek's replies. They lost contact when Joe moved to Ahvaz, a staging camp in the south of Persia from where the orphans left for their journey to New Zealand. He never saw her again.

_______________

Joe was among 67 children 10 years or younger who arrived in Wellington on 1 November 1944 without siblings or a parent.

Initial impressions aside, once they walked through the Pahiatua camp gates the Poles could not have doubted the sincerity of their hosts.

More than 100 local women had arrived the previous Sunday, made beds and provided “vases, flower bowls and blooms to brighten the camp when the children arrive.”5

Gestures such as those, and the kindness of the New Zealand soldiers and other helpers, eased the settling-in process.

“We were divided into age groups and there was an adult looking after every 30 or so children.

“We were told where to go and off we went into these dormitories and we each had a bed, we had sheets and pillows for the first time, everything all nicely done, with a nice little wee cupboard at the side for our things.” Joe smiles at the memory of having his own space, similar to this one.6

“The first thing we did was get something to eat so off we marched into the cookhouse and the army gave us food and after that we all got allocated time to go into the camp stores and be issued with clothing. They had clothing sewn for different aged children and we were allocated with clothing and all issued with a towel and got some pyjamas and a toothbrush, toothpaste and soap and we had to take it all back into our dormitory. It was first time we had a toothbrush. We didn’t know what we were supposed to do with it and we got the toothpaste, pinky stuff that was in a tin [Gibbs Dentifrice].”

“…All of a sudden we had food three times a day… The dining room was always ready.”

The camp was built on the site of the former Pahiatua Racecourse, in the undulating dairying countryside that Joe and his friends came to know well in the next five years.

Their explorations could only begin once the barbed-wire fences were removed, but those watchtowers became magnets for the young boys—soon climbing up to inspect their surroundings.

“In no time they got us regimented. Every time the siren goes, it doesn’t matter where you are, you’ve got to run up there and assemble, it’s your assembly point. And then they would tell you what to do. So this is what used to happen: Every time the siren blew, you had to queue up and go for breakfast, lunch or tea. All of a sudden we had food three times a day.

“We were allocated jobs to do because there were so many of us. We had to clean our toilets, the showers, we had to do the dishes and dry the dishes. We had to polish the floors, do the windows and cut the lawns.

“We went on a roster… there might have been, say, two boys washing the plates and two boys drying them and there would be two boys washing the cups and saucers and another two would be doing knives and forks and things and when it was washed and dried, the places were re-set again, ready for the next meal. The dining room was always ready. Next meal you were told to pick up a plate and queue up to get your food and come back, sit down and eat it. That’s how it was, always ‘clean up after yourself.’ We were rostered to do all these jobs all the time. They kept us quite busy.

“They separated the girls and the boys. There was a definite demarcation line in the camp and we weren’t allowed to go anywhere near the girls’ dormitories.

“… We used to catch little fresh-water crayfish and in no time found out how beautiful they are to eat. We used to ask the soldiers for matches…”

“In the middle of the camp was a huge hall that the whole lot of us could fit in and that’s where the priest said Mass.

“I talked to some of the farmers in the district when we had reunions and asked, ‘What did you think when we used to sing in church, when 800 people used to sing?’ They said, ‘First we didn’t know what was going on.’ Then they realised—because the Poles sing virtually right through [Mass] and you can imagine 800 people singing. We used to do a lot of singing in the evenings, especially in summertime. They used to light bonfires and we used to sing. Adults used to teach us songs they remembered from Poland. That hall was our entertainment area where we had films. They had a bit of a hospital too, a wing where if anybody got sick—as long as it wasn’t bad—they could keep you [in the camp].

“The first two years we were there our education—everything—was in Polish and they were teaching us songs and once we learned how to read and write we had little booklets so we could follow the words. We learned a lot about Poland, about our culture. The adults started telling us stories about when they were young and I think at that stage some of the literature was coming from England from the [Polish] government-in-exile.

“Something must have come from the Polish army in Egypt because I remember the first Polish book when I was learning to read was all about little monkeys and crocodiles and Egyptian things and we learned all the Polish army songs. We liked that sort of thing.

“Some of the adults read us books and taught us about Polish history and that was the first time that I learned about King Jagiełło and of course the boys used to take the Mickey out of me, ‘Here comes Król (King) Jagiełło.’ I was the only one with that name.

“We used to have only a half a day of lessons because we had a lot of chores to do. After breakfast we had to go and clean the toilets, clean the showers and they were huge shower blocks with concrete floors, we had to squeegee things and wash the walls down. Quite often we had to polish the wooden floors in the barracks and doing all sorts of odd jobs.”

Photographer John Pascoe, who recorded the refugees’ arrival, returned to the camp in 1945. His Polish subjects tended to remain anonymous models in his compositions.

Pascoe captioned this photograph “Boys playing a game at a Polish refugee camp in Pahiatua. Shows a group of boys seated outside.” 7

The children roamed farther afield. Joe does not remember the girls often venturing past the Mangatainoka river but the freedom suited the boys rediscovering their broken childhoods.

“Of course we used to look for anything we could find to eat. We used to find blackberries—they were everywhere—and gooseberries used to grow wild around Pahiatua out in the paddocks. We used to catch little fresh-water crayfish and in no time found out how beautiful they are to eat. We used to ask the soldiers for matches and we would take a tin and we would go and put some water in the tin and light a little fire and catch the fresh-water crayfish, about six inches long, and boil boil them… beautiful.”

_______________

At first, language barriers hindered interaction with the local community. Joe remembers concerts and being “quite fascinated” by Scottish bagpipes and their accompanying marching band.

The boys found trouble after a Maori group performed a haka that included the traditional widening of eyes and showing of tongues.

“Of course when they went we started copying them and we got punished for being rude.” Joe laughs.

Films in the main hall were in English and although the boys loved the cowboys and Indians, the younger ones often fell asleep before the end.

Joe played football and absorbed New Zealand's love of rugby.

Here he is seated on the right for a photograph he captioned, ”The victorious Pahiatua Camp seven-a-side rugby team.“8

_______________

As idyllic as life was in the Pahiatua camp, the reality of the war remained close. After military hostilities ended the Red Cross helped reunite relatives in the camp with their families in Europe. But no matter how hard he wished, Joe never received the news he longed to hear.

“I was hoping that maybe now I would find my dad or my dad would find me, that he had survived, but I hadn’t heard from him at all. I didn’t know what happened to him, just that he joined the army. I thought maybe I didn’t hear from him because it was war and now that it was over I might hear from him.

“At this stage two or three boys found out that their dads got killed. That was a very sad part of that time because the adults didn’t give any sympathy or any love to the boys. They were stand-offish to us. I heard afterwards that the girls, if one of their dads was killed, they were given sympathy and cuddles and all that. The boys got nothing. They just told us.

“I remember twice in my dormitory, [the caregiver] just came in and said [to the particular boy], ‘We received notification, your father got killed. He’s dead.’ And that was it. They left. The boys cried and we tried to sort of cuddle them. All the time I was hoping they [the adults] wouldn’t do that to me.”

Polish military and cadet corps personnel, who survived the war in Europe and the Middle East and who refused to return to a communist-controlled People’s Republic of Poland, moved to England from late 1946. They joined the newly established Polish Resettlement Corps, set up by the British government. The maximum two-year service in the PRC became a way to integrate Poles into English society and a chance for families to reconnect and reunite.

By the end of 1946 there was no denying that the children left in the Pahiatua camp were orphans.

New Zealand became a feasible place to start a new life for those in the PRC with Pahiatua relatives. Family homes in eastern Poland—after boundary changes in 1945—were by then part of Soviet Ukraine or Soviet Byelorussia (now Belarus).

The ss rangitiki carried the first Polish parents to Wellington in June 1947. Brothers and sisters arrived later. Some of the Pahiatua refugees found families in Poland and returned there, as later did the priest and three nuns.

By the end of 1946 there was no denying that the children left in the Pahiatua camp were orphans. The New Zealand government gave them the choice to stay in the country until they were old enough to make their own decisions about their lives.

This changed everything for the children. Suddenly they had to be integrated into New Zealand society—which meant learning English.

“They stopped teaching us in Polish. In 1947 they brought in New Zealand teachers. Everything was in English. It was a bit of a nightmare because we learnt phonetically… once we learnt the Polish alphabet, we could read and we could write and somebody could just talk to us and we could write it down because we knew the Polish alphabet. In English, that didn’t work. It was terrible.” Thinking back, Joe laughs.

Joe and friends at the camp. He remembers them as standing from left, Jerzy Juchnovic, Joe (then known as Józek), Jan Makuch, Antoni Sarniak, Jan Niedzwiecki, Kazik Krawczyk, Tadeusz Rozwadowski and Tadeusz Jankiewicz in front.

In the anglicised classroom, “somebody said something and you had to remember what you heard, then write it down… but we persevered with it and in no time we picked up enough so that we could get ourselves understood and we started drifting around [the district] and found out that we could actually earn a bit of pocket money.

“There was about four of us and we were on a golf course and some guy says if you can find a ball, you get thruppence for it… so off we went… we were used to rummaging, looking in the scrub and all that and even along the Mangatainoka river, we were already finding balls… and so off we go and find these balls and we took them to the club and we got thruppence a ball and all of a sudden we’re getting pocket money. And with pocket money, what do we do? We went to Pahiatua, into the shops.

“In those days Woolworths and Mackenzies were big shops. They used to sell all sorts of things and behind the counters usually they would employ nice girls who looked after certain areas. We found out that for a penny you could get broken biscuits. I think the girls used feel sorry for us and break them on purpose because you could buy loose biscuits in those days, you didn’t have to buy the whole packet. It wasn’t very hygienic but for a penny they would give us a lovely bag of broken biscuits.” (This scale and ‘bag of biscuits’ is part of a tableau at the Taranaki Pioneer Village in Stratford.9 )

_______________

“I saved up my money. My big ambition was to get a pocket-knife. Every boy wants to have a pocket knife.”

Joe had been dreaming of one since his first New Zealand Christmas.

“We were so excited. We were going to have a Christmas tree—we didn’t even knew what a Christmas tree was—and they set up a Christmas tree and we were all going to get a present because people in New Zealand donated presents. We were getting all excited… and I was hoping and I was praying I was going to get a pocket-knife.

“On Christmas Day, we were all given a parcel and I unwrapped mine—it was a green wooden duck, a little toy wooden duck! I didn’t know what to do with it and I was running around hoping that I could swap it with somebody else but nobody wanted it. That was the only present I ever got until I got married and my children started buying me presents. I knew I had to buy my own presents.

“We realised we could make some pocket money and started to get a bit cheeky. We went around asking the farmers whether we could give them a hand, do something on the farm, helping them. And that’s what happened. They used to let us do things for a bit of pocket money—even though we didn’t ask for it, but they knew—and we’d help them and they’d give us thruppence or sixpence… Oh, it was great.

“Now you boys, you keep on whistling… because if you stop whistling, I know you’re eating the plums.”

“We got friendly with a chicken farmer, an old Englishman. He had chickens and two pigs, two cows and a huge garden and an orchard and so we asked him whether we could come and help him. We really got on with him and we helped him for the next two years for pocket money. Three of us used to collect the eggs, all that sort of thing. He taught us how to catch eels. He had a creek running through his place and I remember he had a big boiler outside and we used to boil the eels for the chooks.

“At fruit-picking time he used to send us up this big plum tree and he said, ‘Now you boys, you keep on whistling… while you’re picking fruit, you keep on whistling, because if you stop whistling, I know you’re eating the plums.’ It was a big joke. He was a lovely man. I kept in touch with them for years and even to this day still keep in touch with his daughter.”

Their carefree days in the camp ended. Arrangements had to be made for high school as the town of Pahiatua did not have one. Joe remembers a campaign where the Catholic Church asked families living in high school areas to foster or adopt the Polish teenagers. The camp emptied. Joe was among the last 42 boys and about 60 of the youngest girls, who moved to a boarding school in Wellington.

_______________

The camp’s ability to house large numbers resulted in its being transformed into temporary accommodation for the displaced people arriving from Europe after the war. Joe remembers the new arrivals.

The boys, the last of the Polish refugees to leave the Pahiatua camp, had to wait while an orphanage was built in Hawera. They moved in with Mr and Mrs Tietze and two Polish cooks employed to look after them and attended Hawera High School. Mrs Tietze, one of the original caregivers, married a former sergeant in the Polish army with little empathy for his young charges, by then 12 and 13 years old. Joe believes he was about 12 years old in this photograph. His expression suggests his largely untroubled Pahiatua days had gone.

“Tietze had no thread of goodness in him at all. He was a vicious, sadistic man. He used to hit us just for laughing, just for being happy. He had this big rubber hose in his pocket and when he saw us just being kids, running around and laughing, he would give us a whack, ‘What are you laughing about? I’ll give you something to laugh about.’ Or, ‘You must be up to no good if you’re laughing.’

“He was always telling us, ‘You’ll rue the day. When you go to work, you’ll be working very hard for that crust of bread.’ He had a vindictive streak in him.

“One of my mates—who used to work with me on the chook farm—used to wet his bed at first when we were in Pahiatua camp. That sort of thing was looked over because other children used to wet the beds. When Tietze took over, he started hitting my mate. He used to whip him with this rubber thing… it was terrible. There were three of them—out of the 42 of us—who used to wet the bed and Tietze used to try to beat it out of them. I felt really sorry for my friend but I remember he stopped wetting the day he left the orphanage and went to work on the farm.”

The boys at the Hawera orphanage. Joe’s picture is inset because he had recently left.

Inasmuch as the boys hated living under Tietze’s whip and a regime of even more chores than at the Pahiatua camp, they were sorry to discover they had to leave high school—and therefore the orphanage—at 15.

The news surprised and disappointed Joe.

“I had a great English teacher. He took a lot of interest in us boys and got me interested in reading, and injected in me the importance of education—and I wanted to carry on my education. I was doing quite well but when I was 15 they said, ‘Get out.’

“We found out later that for a good donation to the church, the farmers could have us boys work on the farms. I didn’t want to leave high school. I’ve got my testimonial to say that the teachers wanted me to carry on. I did the two years there and in the second year I played for the First 15 in rugby because we got introduced to rugby in Pahiatua. I was very good at woodwork, engineering and electrical stuff, and quite good at maths because numbers are the same in Polish as in English—but I wasn’t any good at English writing. I was still learning English but I had to do French and Latin at the same time so it was a bit much.

“In any case, the Church wouldn’t allow me to carry on with my schooling. They said that was the policy. The boys could go and work when they were 15. When I told the headmaster I was leaving he wanted to know why. He wanted me to carry on.”

Joe, then unaware of the donation scheme between the farmers and the Catholic Church, reiterated the “policy” to his headmaster. He had no choice but to accept another change in his life.

He kept saying, ‘You can’t leave… I paid £25 for you. They promised me that you would stay and work for me.’

“When I first went to the farm I was earning £3 a week and keep and I thought that was good money. I was quite happy at first, saving money. I was doing all right, and in no time I bought a motorbike and I was mobile all of a sudden. I kept in touch with all the other boys because they were all… we felt like family. I could visit other boys working on the other farms and we used to visit the boys who were still in the orphanage.

“But I was there four years and the farmer never increased my pay. I asked him a few times because at that stage I was doing a man’s work and a married man working on a farm was getting £10 or £12 a week and a free house. This farmer wasn’t hard up because it was a town supply farm, so he could afford to pay me extra. Being on town supply you were milking all year round. There was no time off.”

One day, two brothers Joe knew from the Pahiatua camp visited him with a proposition—contract scrub cutting at six shillings and sixpence an hour. Joe “did some calculations,” realised he could earn more than £20 a week, and gave the farmer his notice.

“He kept saying, ‘You can’t leave.’ I kept saying I was. Then he said that ‘they’ promised him I would work for him and stay there. I said I knew nothing about that and that’s when he told me: ‘I paid £25 for you. They promised me that you would stay and work for me.’ The priest and a nun came to talk to me and said, ‘You can’t leave. Where are you going? You’ve got a home here.’ They started lecturing me but I had already made up my mind. I realised that I was being taken advantage of, and they couldn’t convince me. I went with the boys.

“There were four of us. In six months I earned more and saved more than in the four years that I worked milking cows.”

After the scrub cutting stint, Joe got on with making a life for himself. He created successful businesses, married, had children, and came to terms with being unable to discover what happened to his father.

An impromptu trip to the Auckland Museum with his second wife, Joy, changed everything.

At the time, Joe and Joy lived in Whangarei and were in Auckland for a wedding.

“We had a day to spare and went to a war exhibition at the museum. Joy was rummaging through the books, picked one up called friends of england and it opened in her hands on a page that said, ‘If you want to know anything about the Polish Free Army, write to this address.’

“I had given up years ago but we went home and I wrote a letter, telling all I knew about myself and my parents. Luckily I knew my father’s and my mother’s Christian names. It was only about 10 days later when we received notice that they had all my father’s personal possessions!

“We received the parcel through diplomatic channels. There was my dad’s army ID photo [left] and he had my mum’s little wee photo [pictured earlier] and some other army photos with his mates. He had a notebook where he kept his little mementos and all the songs they were learning, but he had a lot of addresses in Poland and I decided to write to all these addresses.

“One of them was to a cousin’s parents. His parents were dead but someone at the post office told him somebody was writing to them and he wrote to me.

“Within two months we booked to visit Poland. First we went to London to visit a mate from the orphanage and we visited my father’s grave at the Loreto Cemetery in Italy because then I knew where it was. And then we went to the Ochodnica Dolna where I was born. That’s how I found out about my family—my father’s and my mother’s.”

Joe had left the village as a six-month-old and hungry for any memories and information, but his relatives did not want to speak about the past.

The house in Ochodnica Dolna where Joe was born.

Joe and Joy dressed in the local national costumes of the Góraly (people of the mountains).

One of the items Joe found in Fransiszek Jagiełło’s military package was his father’s watch. Joe wound it. It ran perfectly—53 years after it had last stopped ticking.

These days Joe Jagiełło has found peace with his past.

© Barbara Scrivens, 2015

Updated September 2017

UNLESS OTHERWISE STATED, ALL THE PHOTOGRAPHS IN THIS STORY ARE FROM THE JAGIEŁŁO COLLECTION.

Joe has written a book detailing his life: Jagiełło, J, One Man’s Odyssey, 2005, First Edition Ltd. Copies are available through: joeandjoy@xtra.co.nz.

ENDNOTES:

- 1 - Image from: collections.tepapa.govt.nz.

- 2 - Image from: www.teara.govt.nz.

- 3 - Evening Post, 31 October 1944,page 6, NATION’S GUESTS, POLISH CHILDREN HOME AT

PAHIATUA, Papers Past through the National Library of New Zealand:

http://natlib.govt.nz/records/17811589. - 4 - Evening Post, 8 August 1944, page 3, POLISH CHILDREN, ACT OF KINDNESS, Papers

Past through the National Library of New Zealand:

http://natlib.govt.nz/records/17776699. - 5 - Ibid, NATION'S GUESTS, POLISH CHILDREN AT HOME IN PAHIATUA.

- 6 - Pascoe, John Dobree, 1908-1972, Photographic albums, prints and negatives. Bedtime at Polish

children's refugee camp, Pahiatua. Ref: 1/2-003658-F. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand:

http://natlib.govt.nz/records/32195333. - 7 - Pascoe, John Dobree, 1908-1972, Photographic albums, prints and negatives. Boys playing a game at a

Polish refugee camp, Pahiatua. Ref: 1/4-001379-F. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand:

http://natlib.govt.nz/records/32057044. - 8 - Jagiełło, Józef, One Man's Odyssey, photographs between pages 294 & 295, 2005, ISBN:1-877391-31-X.

- 9 - Image by Barbara Scrivens. The Pioneer Village is located at 3912 Mountain Road, Stratford:

www.pioneervillage.co.nz.