Janina Marchewa Sarniak

This story is the result of a videoed interview in 1993 that Lonia Sarniak made with her

mother, Janina Marchewa Sarniak, and several conversations between them on 3 July 2005 when for the first time Janina spoke

openly to her daughter about how she survived Soviet tyranny in World War Two.

In 1993 Janina told Lonia how Ukrainain nationalists forced her family off their farm in eastern Poland, how Soviet soldiers

rounded up her family at gunpoint on 10 February 1940 and sent them to a forced-labour facility close to the Arctic Circle in

northern Russia, how they had been granted ‘amnesty’1 and allowed to leave, how her mother died on a

river barge returning from a remote central Asian kolkhoz and how she came to New Zealand as an orphan in 1944.

Lonia’s own research into her family has been supplemented by the work of her partner, Stephen Bryson, who added history and

context. He found recollections from people who, before they too were taken to northern Russia by Soviet soldiers, lived in

the same village as Janina's family.

In a phone call to Lonia on 26 December 2011, Janina's cousin Czesiek recalled how during her trip to Canada in 1976, she had

impressed her uncle, aunt and cousins with her accurate recall of dates, places and events during her time in the Soviet

Union, Persia and beyond. In 1994, a year after her husband, Anton, died, Janina developed normal pressure hydrocephalus and

lost her short-term memory and much of this detail.

The comprehensive Marchewa-Sarniak tome has far more information than we could present on this page. We have abridged

sections that did not pertain directly to Pani Janina.

This photograph of Janina and Lonia appeared in an article in the whanganui chronicle on

16 July 2005. We have given Pani Janina the serif font. Everyone else shares the sans serif.

—Basia Scrivens

SURVIVING AGAINST THE ODDS

Janina Marchewa Sarniak speaks to Lonia Sarniak.

My father Walenty Marchewa was originally from Paplin, a village in the Skierniewice district, near Warsaw in eastern Europe.

At this time Poland did not exist as a sovereign state, its traditional territory partitioned between Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Russia. The Warsaw area was under Russian suzerainty, governed as a “semi-independent” province of the Russian Empire. Paplin is about 10 kilometres from the town of Skierniewice, birthplace of Chopin.

He was in the 14 Pulk Ułanów Jazłowieckich (14 Jazłowiec Lancers Regiment) that became well-known in Poland for its many battles in the 1919-1920 Polish-Soviet War.

Walenty, standing, with a fellow lancer circa 1920, and below.

In 1915, aged 20, he had initially been conscripted into the 24th Infantry Regiment of the Russian Imperial Army at Mariupol2 in south-eastern Ukraine.

After his release from the Russian army3 he joined the newly forming Polish infantry units in Novorossiysk and was assigned to the 4th Polish Rifles Division of General Lucian Zeligowski.

On arrival in Poland the 1st Lancers Division was renamed 14th Jazłowiec Lancers Regiment and Walenty was placed in the 3rd Squadron. He fought against the Ukrainians and Bolsheviks in the 1919-1920 Polish Soviet War in the advance and retreat of Kiev and demobilised in 1921.

My father had an invalid’s pension. He had been badly wounded but I do not know during which war. As a reward for war service the government had given him land in osada Jazłowiecka.

Poland was officially recognised as a sovereign state during the 1918 Treaty of Versailles. Establishing its boundaries proved challenging. The dispute over the eastern borders led to the Polish-Soviet War. Soon after cessation of hostilities (18 October 1920) the Polish government set aside some of the reclaimed land for gifting to army veterans who had displayed valour in battle.

Poland's new Chief of State, Marshal Józef Piłsudski, personally decorated the 14th Jazłowiec Lancers’ regimental colours with the Virtuti Militari Silver Cross and the words: “For the blood, pain and suffering, for not doubting when everyone else doubted in victory and by bravely seeking victory encouraging others to do so.” 4

Later, at the handing over of this land to his former soldiers, Marshal Piłsudski said: “This land, exhausted by the sowing of bloody wars, awaits the planting of peace; awaits those who exchange the sword for the ploughshare and I should count it as an honour if in the future you would achieve as many victories for peace as you have gained in battle.” 5

The settlements of small land owners were called “osady” (singular osada). Jazłowiecka, or Jazłowce, named after Walenty’s old regiment and populated by its demobilised officers and ranks (Walenty was lancer 1st class), was located in Wołyń in eastern Poland, 17 kilometres northeast of its provincial capital, Równe, near the river Horyn and 50 kilometres west of the Polish-Soviet border.

Jazłowce, was one of the larger settlements, about 100 military settlers and their families. It was mainly farms, had a baker’s shop, blacksmith, big church, our school.

Osada Jazłowiecka had a close relationship with its neighbouring settlements, Krechowiecka, Hallerowo, Bajonówka and Zalesie and facilities were often shared across the settlement boundaries. The shop, school or church might have been located within the confines of another settlement, so to the young Janina there would have been little distinction.

My mother Lonia [Leontyna] Marchewa [née Sobolewska] was from the ‘city.’

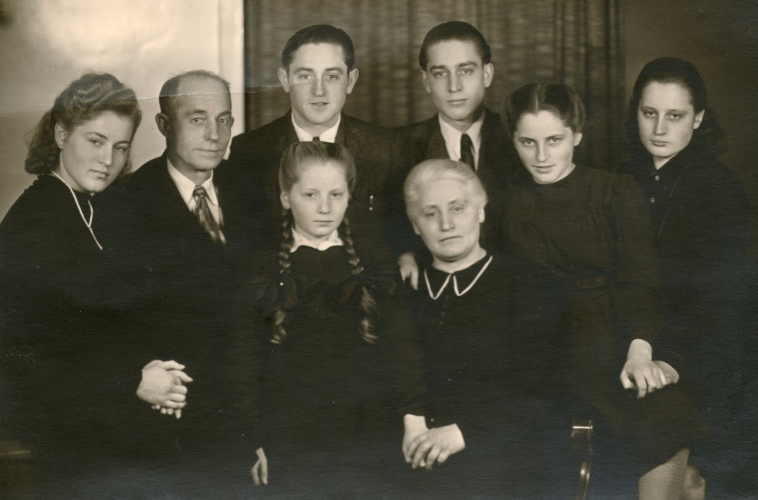

This is the oldest photograph in Janina's collection. Janina believes the woman on the front left is her mother, Leontyna, with her older sister beside her and ptobably a cousin and aunt, circa 1914. They lived in nearby Tuczyn, on the banks of the river Horyn, at the time a major town in the district.

Together my parents farmed the land and built a house. We were all born in the house, my older sister Romka [Romana], me and my two younger brothers Bogdan and Miecio [Mieczyslaw]. My family called me Niusia.

Janina and Romka dressed in summer clothes, the leafy plants, the doll and the wheeled horse suggest that this photograph may have been taken at the time of Janina's second birthday.

The farm would have been on the outskirts of the settlement since Janina remembers osada Hallerowo was on the opposite side of the road. Under the Tsarist regime the entire area had been an artillery range, therefore most of the land to be settled was undeveloped and required much work to bring it into production. In addition to her following comment Janina also recalled her father planted cherry and walnut trees.

The farm was 24 acres and my father grew sugarbeet and tobacco. We also had chooks, pigs, two nice horses, a cow.

The only record discovered to date describes the size of the farm block as exactly 11⅓ hectares. There was a stand of forest where the settlers owned their own blocks of trees. Janina recalled her father’s forest block as being quite close to the river and, although the size of the block is unknown, they were typically about two hectares. The sugarbeet and tobacco industries were both government initiatives. The grower received a concession on his sugarbeet production while tobacco plants could only be grown under licence.

The Marchewa farm, 122 Horyngrod, osada Jazłowce, on the old Tuczyn-Równe road. The haystack obscures the house.

We lived in a brick house. We previously had a wooden house but it had been burnt down by the Ukrainians several times. Each time was when my father was away. I can still remember our neighbours dragging Mum and us screaming kids out of the burning house. After that, my father built a brick house.

Janina’s home province of Wołyń lay within an older part of eastern Europe historically known as Volhynia. Soviet Russia's military defeat at the Polish-Soviet War led to its losing a large part of western Volhynia to the newly emergent Second Polish Republic. The Treaty of Riga, signed on 18 March 1921, officially ended the state of war between Soviet Russia (Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic, Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic) and Poland.6

Since the ethnic mix in Wołyń (Volhynia) was dominantly Ukrainian (64 percent in the 1931 census) the loss of this land from a similarly newly emergent Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (established on 21 December 1918) was not well received by the majority of the local population. Smaller numbers of Poles (16 percent), Jews (10 percent), Germans (2 percent) and Czechs (1 percent) made up the remainder of the population but “essentially the countryside was Ukrainian, the towns were Jewish and the political control Polish.” 7 While the ethnic mix in Wołyń varied according to the political influence of the time, and in the years following the Polish-Soviet War the population in Wołyń became more Polish, there remained a large Ukrainian majority, 90 percent of whom lived in the countryside and were “overwhelmingly poor, illiterate peasants.” 8 This led to much unrest among the Ukrainian peasantry and Polish settlers were exposed to the brunt of many historic grievances.

The torching of settler houses and farm buildings was not unusual. In a political sense Wołyń existed as a buffer between the core of Polish land to the west and the core of Ukrainian land to the east.9

Our house was single storey and had two large bedrooms, large kitchen, and a large combined dining and living room. Romka, Bogdan and I slept in one bedroom and my parents and Miecio shared the other bedroom. I was a tomboy, enjoying what my brothers were doing, climbing trees, active things. I liked riding our horses. We had wooden saddles.

There were two churches10 and on Sundays we kids walked down the road to the church in Hallerowo. Later in the day our parents would take the horse and cart to the other church.

The Marchewa family. Walenty in full military uniform suggests a special occasion. The translated inscription: “As a sign of good memories we are sending you a photograph with our own horses when we returned from church, 22 December, Jazlowce, family Marchewa.” The date may have referred to the day of writing because this is no winter image.

Judging by the clothes and sizes of children, these three photographs seem to have been taken on the farm on the same day. This particular photograph of Janina with her sister may have held painful memories for Janina as Lonia found it hidden behind another in her album.

Leontyna and Walenty Marchewa among the cherry trees on their farm with their sons Bogdan, right, and Miecio.

Although the date is clearly visible on the back of all three photographs, they all have the year either torn or scratched off. The family believes that because they came from Walenty's sister, who lived in post-war Warsaw, they might have passed through the communist censor. The family consensus is that they were taken in late summer, 1935.

School was a few miles away. We would walk there but in winter my father and the other fathers took turns to take us by horse and cart.

This was the senior school located in osada Hallerowo, apparently situated midway between Krechowce and Horyngrod on the Kozlin-Horyngrod road. In the period leading up to the outbreak of war the little group of settlements surrounding Jazłowce, had become a wonderful success story. There was bountiful farm production, a thriving community and a lifestyle for most children verging on the idyllic.

There is not much I remember about those early days but something I do remember are the travelling gypsies. They would call in to the house and ask for food. Mum would always be handing out food and things, so much so that Dad would get annoyed:

“It is all right to give them food but surely not necessary to give them all your food!”

One gypsy woman would tell your fortune in return and I do remember her telling Mum that she would be crossing a long bridge and not to look back as she would not be going back. I remember this because when we were taken into Russia we did cross a long bridge.

On the bench above is Leontyna's brother from Tuczyn, Feliks, his wife, Apolonia, and their daughters Zosia, Genia and Renia, visiting the Marchewa farm during one of their last summers in Poland. Feliks carved the toy horse in the earlier photograph. Bogdan is on the horse on the left and his cousin Janek on the other. Leontyna, peeks behind her brother.

Bogdan standing on a log, probably felled from Walenty's forest stand. Walenty holds the reins. The other three men and the youth at the back are unidentified.

The first I knew of the Russian invasion was when Russian soldiers arrived in our area. Earlier in the day a plane had swooped down low over our school. This really terrified some of the children.

Germany invaded Poland at 4:45 am, 1 September 1939. Days earlier, on 23 August 1939, the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany concluded a non-aggression treaty, attached to which was a “secret additional protocol” to divide Poland between the two parties in the event of any “territorial and political rearrangement” in that part of eastern Europe. This became known as the Fourth Partition of Poland. It gave the entire eastern Poland—and a little bit more—to the Soviet Union and the remainder of Poland to Nazi Germany, and cleared the way for the Nazi invasion of Poland.

As 25 Polish divisions fought the invading German armies in the west, on 17 September 1939 the Red Army invaded from the east. The Soviets quickly overwhelmed the 25 battalions of the Polish Border Defence Corps and advanced into a largely undefended eastern Poland.11

Three weeks later we were forced off our land by a group of Ukrainians. A Ukrainian man who worked for my father had secretly warned us about what was going to happen. This was all at great risk to himself but it gave my parents time to prepare ourselves by moving possessions and food etc. to Uncle Feliks’ house in Tuczyn. My father also buried his gun and army documents on our land. He was an army reservist. Then we went to stay with Uncle Feliks and Aunty Apolonia and their family, Janek, Zosia, Genia and Renia. My mother’s other brother, Uncle Antoni, his wife Aunty Jadwiga, and their family, Czesiek, Staszek, Aniela, Jasia, Romka and Władzia lived right across the road.

Romka accompanying Walenty and a laden farm wagon to Równe. The young man with them may well be the one Janina spoke of as having warned the family.

Although Janina and her family were soon to be taken by the Soviets, immense tragedy befell many of the remaining population of Tuczyn after Germany had driven Russia out of eastern Poland in 1941. The younger members of the Polish community, like Janina’s cousin Czesiek, were taken as slave labour to work in Germany but only a few from the 3,000-strong Jewish community survived. The dreaded Einsatzgruppen killed the rest, either individually or en masse.12

The Russians said to us that we have to go. If we don’t some people are after us, not only us, but the whole settlement.

The Ukrainians formed committees and issued orders for particular Polish settlers to leave their land. This was the situation in Jazłowce, and the surrounding settlements of Krechowiecka, Hallerowo and Bajonówka where it appears that the better farms were being selectively acquired.13

Dioniza Gradzik: “Yet (for example, the settlers would provide work, and loan grain, flour and potatoes in the hard times) throughout that first night when the Soviets overran our district, horrific deeds occurred. The majority of the settlers were murdered as was the school’s head teacher, Stanislaw Kajtowski. Only those who hid in the fields were saved. That night father was killed in the garden at the back of the house.” 14

After allowing a short period for the Ukrainians to exert their new-found domination over the ethnic Poles the Soviets moved to plunder the whole of eastern Poland. They began to systematically extinguish all traces of the Polish state and the former rights of the Polish citizen. The term often used was the introduction of a new order through the “sovietising” of their new conquest. Ukrainian families crammed into Polish houses (often as enforced lodgers) and the education system was turned on its head.

“That autumn, the children did not go off to school because everything was topsy-turvy, teachers were dismissed, headmistresses substituted, the syllabuses changed and the Russian language made obligatory.” 15

In late October 1939 “elections” to the local councils were organised, and a few days later meetings of the Supreme National Assemblies of Byelorussia and the Ukraine passed resolutions annexing the Polish territories. By resolution of the Supreme Council of the Soviet Union on 1–2 November 1939, all Polish citizens living in these annexed territories became citizens of the Soviet Union.16

The Marchewa and Sobolewski families, probably taken early in the winter of 1939–1941 after the Marchewas were forced out of their home. In the front row, Bogdan is far left and Miecio third left; in the middle row, Janina is third left; in the back row Romana is second left, Leontyna third left and Walenty is far right. Czesław, back row left, is the only identified cousin.

One day Uncle and Mother went to town to buy salt. Uncle had killed a pig. That was lucky for us as we had something to take to Russia. There were lots of horses and sledges. Uncle remarked to Mum, “Look at those horses, the Russians must be getting ready to run away from Poland!”

The family appears to have had little inkling of their fate. For those living closer to the railway tracks, the evidence was more foreboding as vast numbers of cattle wagons assembled. The Soviet authorities were steadily implementing their plan and used the “autumn census,” taken soon after the invasion, to compose lists of names of all those soon destined for arrest and deportation into the USSR.17

Then just a few days later (10 February 1940) the Russian soldiers came to arrest us. It was about 2:00 a.m. Soldiers with guns on their shoulders came into the house. My father was shoved against the wall and held at gunpoint. My uncle was told to wake the rest of our family. My mother was given about half an hour to pack some food and warm clothes. We were told that there was no need to take much as there would be plenty where we were going. Us kids were all crying and clinging to Mum. My uncle and his family were not deported as he was not a military settler.18

We were loaded in sledges and taken to a station many miles away. We were (then) loaded into a goods train. The Russians said we were being taken away for our own protection.

Janina further recalled that the family was taken by horse-drawn sleigh to Kostopol station, 25 kilometres northwest of Tuczyn. There they were loaded into cattle wagons with about 40 persons per wagon with the smaller pieces of luggage. The larger pieces of luggage went into a goods wagon. It was snowing “lazily with huge flakes.” The family would have been unaware that they were a small part of a mass deportation taking place across the entire eastern Poland.

I don’t remember how old we all were.

Walenty 44, Leontyna 45 or 46, Romka 14, Janina 13, Bogdan 10, Miecio 8 or 9.

I remember very little about the route to our final destination other than the station at Zdolbunów in Poland and passing through Shepetivka just over the border in Russia. We travelled on the train for a few weeks, maybe four to five weeks, I’m not sure. I don’t recall anyone in our wagon dying. They may have, but I don’t remember. I do know that people did die in our train, as well as in other trains.

Others aboard Janina’s particular train have provided details on their shared journey into exile (Jadwiga Pleciak, Jan and Bogdan Kulik, L Cabut, Danuta Maczka, and Jadwiga Zielinska): Firstly the loaded wagons at Kostopol are sent down the line, coupling up with other loaded wagons at Lubomirka. On the third day these wagons were moved on to Równe, about 40 kilometres away, where they were coupled to “a very long train” and with little delay moved on to Zdolbunów, a large station 10 kilometres south of Równe. Here the narrower Polish railway tracks meet the wider Soviet gauge. People and possessions were transferred into the Soviet “tyeplushki” standing on the opposite side of the track.19

The “tyeplushki,” or heated goods wagon/stove carriage, is a goods wagon modified for the transportation of people, having an iron stove, bunks or rows of timber slats for sleeping and storage, a hole in floor for a toilet and with a capacity of about 70 persons per wagon. Six days after their arrest Janina and her family crossed the Polish-Soviet border and arrived at Shepetivka station in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, 60 kilometres southeast of Zdolbunów. Their train had 23 wooden cattle wagons, each with a double door sealed shut and two narrow barred windows high on opposite walls. It contained 1,110 exiles, guarded by soldiers from the Red Army's 147th Battalion of the 11th Brigade and an officer-in-charge named Bielczenko.20

Moving both north and east, through Korosten and Ovruc, they passed beyond the Ukraine and into the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, now known as the Russian Federation. Next came Gomel, Bryansk, and Orel, crossing the river Don some 300 kilometres south of Moscow, and a turn north. They passed ever deeper into the Russian interior; Tolstoy-Lev, Aleksandrowka, Ryazan, and Orekhovo, snow covered fields, forests, villages, towns and cities.

There was extreme cold, very little food and limited water, the hygiene conditions were terrible and people were dying, in particular the old and the very young. Then it was Vladimir, Gorky, Kirov, and a final turn north. Two days later, in the early morning of the 18th day of captivity, on 27 February 1940, they reached Kotlas in Archangelsk Oblast, North Russia.21

Large numbers of Polish POW and political prisoners had been arriving in Kotlas since the first days of the Soviet occupation of eastern Poland. They met a different fate: They were destined for some of the worst atrocities of the Gulag and worked in the extreme polar conditions of the north, building the infamous Pechora railway.22

We were taken to a posiołek deep in the forest near Kotlas. There we were accommodated in barracks. We had a room about the size of a sitting room and there were ten of us living in it. There was no heating.

Jadwiga Pleciak: At Kotlas, “we were lodged in a school hall for the night (26/27th)… outside there was a very keen frost (-40°C) and next day (27th) we were shipped (south) by (horse-drawn) sledges along the frozen (Northern) Dvina some 25 kilometres to a small place called Privodino where we hauled up for the night. The following day (28th)… we travelled on, but this time on a narrow gauge railway through the forest to posiołek Kotovalsk.” 23

Janina must have made this same journey and the posiołek that Jadwiga described is almost certainly Statzia Mlodikh (Stacja Molodykh or “Youngster’s Station”). This was a small camp located on the forest railway about 30 kilometres past Privodino and about four kilometres away from posiołek Kotovalsk, itself deeper in the forest and the destination for some 200 deportees from the train.

The next morning my father had to go to work. My mother was already too ill to go. She had a heart condition and was given a certificate exempting her from work. My father was put to work in the forest clearing trees.

Other survivors recall how several days were given to settling in before work began. Then, “in the dreadful cold and heavy snow which continued unabated it was grinding work and without suitable nourishment a person quickly became exhausted.” 24

Danuta Maczka described how after a few weeks her family was moved from posiołek Kotovalsk to posiołek Statzia Mlodikh and “are placed in a smaller hut. This room is for three families… As we now have a family bunk bed we no longer sleep on the floor. Between the huts are wooden planks we use as gangways… It is surrounded by forest. The narrow gauge railway comes here so I do not feel so cut off from the world… Next day (Easter Monday) they have noticed that I am now 15 and am told I will have to go to work, starting next day. We girls are told to clear snow from the rail tracks. I work all day, my hands and back ache. I am paid three roubles, my first earned money… 10 April, two months after deportation. Now I work in the forest, removing branches from felled trees which men then stack in big piles that are soon covered in snow. The logs are then taken to the depot and loaded on wagons. The branches we burn on the spot. As it is now spring, forest work ends. We go for a walk with a group of people and discover violets which remind us of the sacred dell called Karlowszczyzna on osada Krechowiecka…” 25

We stayed there for quite a while, several months, and when the snow started to melt… —a lot of people were already dying and they just buried them under the snow and that’s it— …and when the snow started to melt, that was springtime, nearly all the bodies started to come out because they were only covered with snow. They quickly shifted us to another place…

Lonia: Did you see all this?

No I didn’t, no I didn’t, but that’s a fact. No, I personally didn’t. I didn’t even see a dead body then because nobody had died in my family then. I’d never even seen a dead body in my life. But then they shifted us to a camp with a big factory, something that looks like Kawerau (a New Zealand pulp and paper mill). My father worked there.

Danuta Maczka: “15 April (last entry for posiołek Statzia Mlodikh). We and a few other families are moved to a new place. We travel on the railway.” 26

This new camp is posiołek Monastyriok (approximately 92 families and 600 internees). It is back along the forest railway near the rail terminus and appears to have been located about three kilometres north of the town of Privodino. It is situated on the banks of the Northern Dvina and has a big timber milling operation and a small wood burning power station nearby The waterway is a side channel and back-arm of the Northern Dvina and also known as the Privodino. Posiołek Monastyriok and all the other camps linked by this forest railway are in the very south of Archangelsk Oblast and just a few kilometres north of the territorial boundary with the more southern Vologda Oblast.

We stayed at this camp until after the amnesty. There was a large sawmill and most people were put to work in it or in the forest. The work began at first light and people didn’t finish until dark.

Conditions in the camp have been described as “appalling, but at that time we had no idea just how much worse they would become.” Also, at first “we were not hungry, because we exchanged some of our bedding and clothing for potatoes and other food.” 27

Compared to their earlier camps, in Monastyriok the families enjoyed better living conditions, each family having their own space divided off by wooden partitions, sufficient bunk beds and an iron stove for heating that could also be used for cooking. There was also a communal kitchen. The following autumn they collected berries and mushrooms from the forest, “which were plentiful that year.” The “local people said they could not remember such a glut for many years.” The Poles dried the mushrooms and made cordials and jams with the berries.28 No guards stopped the inmates from moving around Monastyriok on their allotted tasks but they required passes for going farther afield.

Danuta Maczka: “The enormous gate at the camp entrance frightens me. It is surrounded by a tall wooden stockade with guard towers at its corners and looks like a prison. However I soon discover that the towers contain no guards and the gate is only shut, but not locked at night… The name of the posiołek comes from the Orthodox church, possibly a former monastery, which still stands and amazingly still has a dome and a cross but it no longer serves as a House of God, but as a storeroom, canteen and shop.” 29

The church and various other buildings were located outside the camp stockade and Janina recalls that the cross had fallen on the ground.

_______________

Lonia recalls a story from Janina:

Apparently posiołek Monastyriok was very close to a big river. This was a particularly sad recollection for my mother.

There was forest across the river where wild blackberries grew. There was also a boat service available and her mother would give Mum a coin for the passage and send her off to gather the berries.

Although food was very scarce in the camps, Mum says that sweets were readily available (and also cakes, although these were expensive). Mum would never use the boat service, instead together with two of her girlfriends, they would make their way across in their own little craft, two or three planks tied together and propelled by paddles. (Satellite imagery today shows the narrow point for a river crossing to be about 125m.)

The prize was keeping the coin and buying the sweets, and Mum never told her mother about their little secret.

One day, unbeknown to Mum, her two friends set off across the river without her. Their raft capsized and the two girls were drowned. From then on, Mum always used the boat service. Unfortunately, after so many years she can't now recall her young friends’ names.

_______________

We had little choppers. We used to go after school and chop small pieces of wood for burning in the factory. They paid us for it.

We were told that we were to stay there until we died. Also, if you do not work you do not eat. Everyone over 15 years old had to work. Children under 15 had to go to school. My mother was too sick to work.

The basic rule of camp life was “Kto nye rabotal, nye kushal” or “Who didn’t work, didn’t eat.” In addition, there were usually two levels of payment. The first payment was “a mere pittance” but if a work quota was completed, often requiring a herculean effort “as befitted a Stakhanovite” and far beyond the physical capability of almost all, then “a larger ration of bread (400–600 grammes) was provided, plus additional coupons, redeemable in the canteen.” But, as many survivors recount, the shop or canteen often had no food and “we were thrown back onto our own strength and physical endurance. Half-starved children and the old were the first casualties of emaciation and illnesses, such as night-blindness, scurvy, typhoid and dysentery.” 30

My father became ill so he was taken to the hospital. Now there was no one in the family who was able to work so we had no food.

Janina’s younger brother Bogdan recalled that when their father was in hospital they had to sell their “Polish stuff” to buy bread.

Mum stopped sending us to school as we were too hungry. After a few days the camp commandant came to see Mum to find out why we weren’t in school. As a result we were issued a bread ration even though none of us could work.

Commandant Organ was in charge of the camp and it is commonly agreed that they were lucky to have him as he is considered to have treated them fairly. This was not the case in many other camps where conditions could be brutal.

Mum used to visit Dad practically every day in hospital. When he was discharged from hospital he was given a lighter job. He had to rise at 3:00 a.m. to prepare the horses for the other workers to take to the forest. In the evening it was his job to settle the horses for the night. Every morning my father would also wake me at 3:00 a.m. to go and queue for the bread. Previously my sister used to go but she would often come back in tears, without bread, after being pushed out of the queue.

Up until this period I had always been very shy and a polite child but now I started to toughen up. I was determined that no one was going to push me out of the queue and I was going to bring bread back to my family. Mum said that she relied on me to get the bread. If anyone pushed me I pushed back as hard as I could. I didn’t care who they were, I was going to get our share of bread.

Although we had spent over 18 months in the posiołeks, we had managed to survive as a family. In the early days things weren’t that bad as we had brought some food from Poland and also received occasional food parcels from our relatives back home. After the first few months the food ran out and that was when things got really hard. But even then it wasn’t as bad as it became during the time in the south.

The winter in north Russia was very long with the temperature for six months of the year, mid-October to mid-April, never rising above freezing point. Then for three months, June through August, it was summer with temperatures reaching above 20°C. “But it was hard to choose which was preferable, the dry winter or the swampy, mosquito-infested summer.” The summer could be very hot with daylight extending almost the entire 24 hours, therefore plants and vegetables grew rapidly. “By the 20th August we are eating new potatoes from our garden.” 31

The amnesty was announced in August (1941) and we left in October. Dad later told me, after Mum had died, that the worst decision he ever made was leaving the camp at that time. He felt that had we stayed and somehow survived the winter then eventually we might have made our way back to Poland. But everyone was terrified of the approaching winter and was desperate to leave and head south.

Nazi Germany had turned on her ally the Soviet Union and launched full-scale war, Operation Barbarossa, on 22 June 1941. At first the war went very badly for the Soviet Union with the Red Army collapsing before the advancing Axis Forces (Równe and Jazłowce captured within the first week). The risk to the USSR's very survival soon dictated that Stalin seek urgent rapprochement with the Allies. This led to the emergence of the ‘amnesty’ or protocol for the release of the Polish citizens held captive in the Soviet Union. The intricacies of the political process included the formation of a Polish army on Soviet soil.

The first discharge documents were issued on 5 September 1941. Records show that Janina and her family received this early discharge date but Janina recalled that they delayed their departure for a month.

We were heading south so my father could join the army. I don’t remember much about how we got there as it was a long time ago. What I do remember is the train sometimes stopping in the middle of nowhere for days at a time.

The train journey apparently covered 7,000 kilometres in 18 days. Janina’s dominant memory of the journey is that the family eventually reached Kirghizia in Soviet Central Asia, and they also made two trips along the river Amu Darya.

Bogdan: “Then the time came when we were released and we went on an incredibly difficult journey. We travelled in wagons. We reached the Amu Darya where we were unloaded from stinking wagons and were loaded into large boats. We travelled (in the wagons) for 18 days but we only had bread for 12 days. How were we supposed to manage?”

L Cabut was another survivor who left posiołek Monastryriok at the same time as Janina and her family, and from all indications almost certainly shared the same train journey south. He described their route as having passed through Vologda, Kirov, Sverdlovsk, Czelyabinsk, Bernaut (or Barnaul), and south into Kazakhstan, Alma-Ata (west into Uzbekistan), Tashkent (next turning east into Kirghizia and a 400-kilometre detour to near the railhead at the top of the Ferghana Valley), Andijan and backtracking down the Ferghana Valley and on into Uzbekistan, Samarkand, and finally crossing west into Turkmenistan, to Farab on the river Amu Darya across the river from Chardzhou (now known as Turkmenabat).

“Here, loaded onto metal barges, squeezed below deck in ghastly conditions, we were eaten by lice.” 32

They travelled more than twice the distance of their earlier consignment into exile. This exodus, involving perhaps upwards of 300,000 Poles fleeing the USSR after their release from Soviet captivity, has become known for the enormity of the hardship suffered by those who survived, and the huge loss of life that occurred en route.

The Russian soldiers loaded us onto a cattle boat on the Amu Darya river.

The Amu Darya is a major river of Central Asia, taking its waters from glaciers high in the Pamir mountains and the Hindu Kush and flowing north-westerly for 2,400 kilometres through Oxiana (the central border region of Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan), then on through northern Turkmenistan, passing Farab, skirting southern Uzbekistan and finally on through Karakalpakstan, discharging into the inland Aral Sea.

The river was navigable for more than 1,400 kilometres and from Farab to the Aral Sea the waterway varied between 500 and 1,500 metres in width. The cattle boats, steel barges, were towed by steamboat. Janina and her family, with L Cabut and his family, were towed down-river towards Nukus, the capital city of Karakalpakstan, deeper into the confines of a vast desert.

The boat had ice down the sides and it was very cold. We were only given soup and bread, that’s all.

Survivors recall that the soup was thin watery gruel with a piece of bread. Possibly unbeknown to Janina’s family was the apparent “spontaneous advice” being offered by “anybody and everybody,”—“Don’t let them take you on the barges on the Amu Darya because others have ended up worse off that way.“ 33

After travelling on the boat for a week we were unloaded and sent to a kolkhoz.

Three other survivors have been able to provide fuller description of this particular stage of the journey south:

L Cabut: “The barges were towed by tugs towards Nukus. After a while we made our first stop, where some families were left behind, mine being one of them. We were simply left in the darkness on the river bank, surrounded by the empty steppes. Some hours later a local Uzbek arrived with arbas (very high, two wheel carts) drawn by camels. We loaded our few possessions onto these peculiar vehicles and set off for our destination. Our accommodation proved to be mud huts with openings acting as doors and windows. We all worked planting cotton and were paid in dzhugara (either flour or grain) and katyk (sour milk). That was December 1941.“ 34

Dioniza Gradzik: “In (Farab) we were told to leave the train but this wasn’t the end of our journey. For three days we sailed on goods barges along the Amu Darya. In the collective farm (near Turtkul, on the left bank of the river) to which we came we worked in the fields picking cotton. The dry husks tore at our bare hands and the scratches turned septic but our main concern was still hunger. We were forever dreaming about eating and in this place it was difficult even to acquire drinking water. In the numerous little lakes the water was clear but salty. Mother was chronically sick and we’d never seen a doctor since we left the north. We stayed there for less than three weeks, when we were told to pack our bundles and go back. This time with the flow of the river against us our journey took five days…” 35

Danuta Laskowska's family was off-loaded at Nukus and sent another 90 kilometres by arba into the depths of Karakalpakstan, where in a kolkhotz: “We worked alongside the local population picking the mature cotton. The people lived in cabins without chimneys, but with a mere hole in the roof for the smoke… I had never before witnessed such primitive living conditions.” The work lasted for just two weeks before they were returned up-river and back into Uzbekistan.36

The people were very kind to us but they were poor themselves. They couldn’t give us anything. But they grew cotton. My father was already very sick, my mother couldn’t work and my little brother was too young to work. So my sister, my brother, and myself, worked in the cotton fields. In the evenings we went to the Kirghizians’ houses as they were our bosses. All we worked for was a piece of bread. We had no pay or anything, just a piece of bread. We were quite happy over there because the people were so nice.

These people were unlikely to have been actual Kirghizian since Kirghizia is a long way east of the cotton fields of Karakalpakstan. The political boundaries and regions of the Soviet Union could be obscure, certainly nothing obvious from the inside of a moving train. Quite possibly the train had stood for a time at the rail head in Kirghizia, with the high peaks of the Tien Shan clearly announcing their arrival in Kirghizia. Therefore their rail journey ending a few days later might have suggested that they were still in Kirghizia.

Janina also remembered another region, somewhere along the banks of the lower Amu Darya within the traditional home of differing Turkic people, the nomadic Karakalpak. It is a marginally productive land surrounded by immense tracts of desert. To the north and east is the vast arid waste of the Kyzyl Kum, a red sand desert, and to the west and south is the similarly vast expanse of the Karakum or Kara Kum, a black sand desert, among the poorest of the economic sub-regions of Soviet Central Asia.

I remember seeing a dog which I approached and wanted to pat. But it bared its teeth so I got frightened and ran away. It chased after me and I fell over and cut my leg. I didn’t tell Mum but later the leg got badly infected so I had to tell her what had happened. She said that it wasn’t a dog but a jackal.

This is the golden jackal and unless rabid it is not generally a threat to humans. On the edge of the Karakum desert it feeds on desert rats, lizards, snakes, fish and muskrats.

One day we were in the field when the Russians came and told us to go home. “You are no longer required to work here!” When we went home my father told us we can’t stay here. The Russian officials were also there and told us, you are no longer required: “You have to move from here because you came here by mistake.”

So we were loaded onto another boat and sent back along the river. Mum was very ill in a room that was being used as a hospital. I was sleeping next to her when my father came and woke me: “You have to go down below and join your sister and brothers.” I awoke very early in the morning and ran to see Mum. I knew as soon as I saw her that she was dead. I ran crying back to my sister and told her that Mum was dead. We sat there crying and Dad came in. He told us Mum wasn’t dead but I told him I knew she was as I’d seen her. Dad then admitted that Mum had died but told us not to tell our little brothers.

Dad and another man were able to row to the shore and bury Mum on the land. Normally, as the people died they were thrown into the river but somehow my father managed to bury Mum on land. He hired a fishing boat that came alongside and he buried her somewhere on the river bank. I don’t know where. Mum died on the 1st December 1941. I am certain about the date because that is something you don’t forget, the date of your mother’s dying.

Leontyna was 47 years old.

Dioniza Gradzik on the conditions prevailing on these barges: “Crawling with lice, people slept side by side on the deck. It was 26th November 1941 and it was very cold and raining. There was very little air under the tarpaulin we’d thrown over us. Those sick with dysentery and in a hurry to use the toilet often didn’t make it and anyway there was a permanent queue in front of each of them. We drank water from the river over the banks of which toilets were suspended. We received no food. All through the night one was assailed by the moaning of the sick and the crying of children. This was the most ghastly part of our journey.” 37

Almost 70 years later, in October 2011, Janina commented that when one went on a large ship or boat nowadays “you might think about a lot of things” but then “all you could think about was hunger.”

The trip back along the Amu Darya lasted about a week. Then Dad and us four kids carried on trying to get to the army.

The Marchewa family were deposited back on the riverbank near Farab, but their situation continued to deteriorate.

Telesfor Sobierajski: From Karakalpakstan… “by the same transport (arbas) we returned to the same river and in the same barges sailed back to the same place (Farab) from which not long before we’d sailed in the opposite direction. Right there on the banks of that vast river we went through a period little better than a term in hell. The nights were bitterly cold, we had no means of lighting a fire and also we suffered from terrible hunger. Whatever we’d once had we’d already used and in this place it was impossible to buy or exchange anything from or with anybody. Very often the only food was grass and if it contained a worm so much the better. This appalling situation came to a head when we were again sent out to many different collective farms… where we lived in kibitki, sheds made out of clay and intended for livestock… There was neither work nor food but worst of all was the feeling that none would ever find us here. Such were our conditions for Christmas 1941…” 38

_______________

Somewhere along the way we were rounded up by the Russian soldiers and sent to another kolkhoz to work.

This kolkhoz was almost certainly near Kenimekh, located deep within the arid wastes of the Kyzyl Kum. Janina has little recollection of exactly how her family arrived there.

Tadeusz Walczak, who went there directly from Tashkent, probably in January 1942: “We were sent to Kenimekh, a kolkhoz not far from Katta-Kurgan… food was as hard to come by there as it had been during our journey south, or in the north. We were quartered in a mud hut without any furniture, and we had to sleep on the ground. There were other Polish families in that and in other kolkhozes nearby. We were driven out to work in the cotton fields. There was hardly any pay to be had, and the rations were no better than starvation level.” 39

L Cabut and his family had separated from Janina and her family during the trip along the Amu Darya: “Towards the end of that month (December) we were returned to Farab. There we met a few thousand deportees all similar to us. Typhoid and dysentery raged there. It was cold, there was a lack of food and we had no warm clothing, having already exchanged that for food on our way. After a few days, all those of us camping out in the open were taken to collective farms a long distance from Farab. Our family ended up on a (collective) farm in Kenimekh and then we discovered that the Polish army was not far from there in Kermine.” 40

Kenimekh (Kanimech) today is a small town in central Uzbekistan, about 200 kilometres north of Farab, 100 kilometres west of Katta-Kurgan and some 30 kilometres west of Kermine (now known as Navoi).

The people were very poor. There was nothing to eat, nothing to do, no work available. The only work to do was irrigation, digging holes for water. But they said we were children and couldn’t do that work. We were so hungry. I remember my sister making flat cakes out of some flour that we managed to get.

The flour was probably from sorghum, a drought and heat-tolerant grass especially important in arid regions where its grain is one of the staples for poor and rural people.

There was no water to drink, just holes in the ground with dirty water. We had to boil the water before drinking it. I remember Bogdan and myself boiling the water but we did not have enough wood. There was only sufficient boiled water for our father, Romka, and Miecio, so we agreed to lie to Dad to say all the water was boiled. Otherwise he would not have drunk his share.

Dad became very ill again. He had frost-bitten feet and was too ill to work, so he was sent to the hospital. We kids weren’t wanted on the kolkhoz as we were too young to work, so no good to anyone. We were sent off to the hospital with our father. My youngest brother Miecio was also becoming very ill. At the hospital Romka, Miecio and I shared a bed and Bogdan and my father shared another. While we were at the hospital I caught typhus. This is also what my youngest brother had. There was an epidemic of typhus, so many people around us were catching it and dying like flies. Then Dad recovered enough to be discharged and he and Bogdan went back to the kolkhoz.

The cart from the kolkhoz was coming to collect Romka. Miecio said to Romka, if you go home I will die tomorrow. The cart didn’t come and the next day Miecio died. Later that day the cart came and Romka was taken back to the kolkhoz.

Miecio died in Kenimekh, I remember that was the place where he died. I remember him lying there, bones poking out everywhere, just a little skeleton covered with skin. I was lying beside him, not realizing that he had slipped into a coma. I tried to wake him to tell him that they were bringing us some food. As I was shaking him a nurse yelled at me to leave him alone: “Can’t you see he’s dying?” I didn’t know Miecio was dying and this is my guiltiest memory. If I hadn’t tried to wake him he may have died sooner. By shaking him I interrupted his dying process and he took a few hours longer to die. And he suffered so much. To this day I still feel guilty for prolonging his death.

The rapidly weakening population of escaping Poles succumbed to a diversity of diseases: malaria, jaundice, scurvy, dysentery, epidemic typhus and typhoid.

Miecio died on the 10th February 1942. I remember the date as it was exactly two years to the day since we were deported.

Miecio, the youngest of the family, was just 10 or 11 years old when he died.

After he died, they wrapped him in a sheet and took him away and buried him somewhere in a communal grave. I don’t know where. So many people were dying that they were mainly being buried together in unmarked graves.

Bronislaw Wawrzkowicz: “almost 1,500 people were buried in a communal grave just outside (Kenimekh).” His story mirrors Janina’s. In 2001, a Polish construction company based in Tashkent went to Kenimekh and transformed the surviving Polish military cemetery from a state of great disrepair into a beautiful setting of peaceful eloquence. This included the exhumation and reburial of remains and the construction of a marble memorial with the names of the dead, 337 ranks and officers.41

Bogdan came to visit me in hospital and said Dad was thinking of joining the army. I am not sure when that was.

I said, “What about us?” And Dad said he would be making arrangements with the orphanage. Romka and Bogdan went into the orphanage and Dad left to join the army. I never saw him again. I wasn’t able to trace him after the war but I knew he was dead. If he was alive I’m sure he would have found Bogdan and me eventually.

Janina did eventually discover what had happened to her father. Among her papers is a copy of his death certificate. It shows that Walenty died less than two months after Janina last saw him, on 10 April 1942, at the Polish army hospital in Wrewskoye (Vrevskii, now known as Almazar, 50 kilometres southwest of Tashkent). He was buried the next day in grave number 41 of 50 at the Polish cemetery. The cause of death was given as bronchitis. He was 46.

When I started to feel better I discharged myself from the hospital. They didn’t want to let me go as they said I was still too ill but they couldn’t force me to stay. I wanted to be with Romka and Bogdan. I left the hospital but was too weak to walk so was crawling on all fours.

I had no idea where I was going. I had stopped in front of a little bridge when I saw two soldiers ahead. I recognised the Polish white eagle on their caps but I spoke to them in Russian as I was too frightened to speak in Polish. I told them I was a Polish girl and they spoke to me in Polish. They asked me where I was going and I told them, I don’t know. They asked about my family and I told them that I didn’t know where they were. They carried me back to a big building where other people were staying. They said there was an orphanage where I could go. I was taken there in a lorry. It was many, many miles away but when we got there everyone had left. I stayed in the building and the soldiers delivered a meal each day.

By then units of 7th Infantry Division were stationed in Kenimekh, including the 7th Reconnoitering Detachment and the 24th Infantry Regiment.

The orphanage was where Romka and Bogdan had been sent but all the children had already been moved. I think they may already have been taken to Persia but I’m not sure. The orphanage already had my details as my father had earlier made arrangements for me to go there when I was able to be discharged from hospital.

The first of two military evacuations to Persia took place in late March/early April 1942. The children in orphanages were part of these evacuations. The best estimate is that Janina was housed in this orphanage from early April until August 1942, when the second military evacuation took place.

At first, there was only myself and an older girl. She had known my sister and offered to look out for me. Then more children started to arrive. I remember the first ones who arrived were two little boys about five or six years old. Their mother had died so their father brought them to the orphanage and went to join the army. By the time we were ready to move to Persia there were about 200 children.

General Anders came to visit the orphanage. He promised, “You children, you will come with us and one day we will all meet up back in Poland.” But we never did go back.

This is the orphanage that Maria Tarasiewicz described in detail. Her family arrived in Kermine, August 1942, and her mother was persuaded to place Maria and her brother Alek, “at the Polish orphanage about 25 kilometres from Kermine,” where they would be under the protection of the Polish Army:

“The orphanage building was a large clay abode in a rural area, surrounded by Uzbek-owned market gardens, where they grew melons, cucumbers and loganberries. These were very tempting to starved Polish children. The boys and girls slept on straw-covered floors in separate, long dormitories, each provided with an adjoining room for staff. An outside well provided us with drinking water. We washed ourselves by the well and our clothes in a nearby stream. Toilets were simple dugout hollows in the earth outdoors, screened off with calico. Flies were abundant everywhere as the temperature was still high in the late summer. We soon contracted dysentery from the other children, who relieved themselves everywhere in the open, usually unable to reach the primitive toilets in time…

“Every day dying babies and starving Polish orphans were handed over to the staff of the orphanage by desperate parents and army personnel. Many children were emaciated, walking skeletons suffering from chronic dysentery. The worst cases were admitted to an army hospital, others remained in the orphanage. We became accustomed to living with death all around us, because someone died every day. We received army rations to sustain our weak bodies, but we were unable to absorb the nourishment provided. Luckily, with Uncle's assistance, Mother obtained the position of the Matron of the Polish orphanage hospital. Her nursing qualifications once again helped her, this time to be reunited with us before our imminent departure from the Soviet Union. Hygiene was difficult to maintain in our primitive conditions. The constantly arriving new orphans were infested with head and body lice. To control these insect infestations clothes were regularly disinfected and our heads were shaved. This gave us an appearance of inmates of a concentration camp, especially as most of us had been reduced to mere skeletons.” 42

All the moves happened late at night to hide us from the Soviets. I am not sure when we made the move to Persia.

Throughout this time the Soviet authorities made it difficult for the Polish authorities, including claiming that all orphans should be placed in the care of the Soviet State. The Poles in turn were attaching the orphanages to the army thereby providing the children with some degree of protection. There was fresh urgency to escape the Soviet Union as there were strong indications of an impending closure of the Soviet-Persian border.

We were taken by army trucks to the big city Tashkent. We were then taken by train to Ashkhabad in Turkmenistan.

Tashkent was 400 kilometres to the east and where the train carrying Janina and family had passed through some 10 months earlier. Ashkhabad was another 1,200 kilometres back to the west.

Maria Tarasiewicz: “Finally our train departed from Tashkent bound for Ashkhabad, where Polish army vehicles were to meet our train on arrival. Our train journey to that destination took over a week. Mother was the only trained nurse caring for over 300 people, most of them children. Her staff assisted with great devotion, tending the sick and the dying orphans of mixed ages and varying degrees of emaciation. Some children, like my brother, were too weak to walk without assistance, while others could not even muster the strength to sit.

“On the way our train stopped at many famous towns such as Bukhara, the centre of fertile lowland and Samarkand an ancient city situated at the foothills of high mountains. Samarkand was an historical city with beautiful shrines, the city through which ancient Greeks, Mongols, Persians and Russians passed as conquerors. Now it was the freedom-seeking Poles’ turn to pass unobtrusively through it, catching only a few glimpses of this historical splendour, from the speeding train.” 43

The Poles travelled back along the Trans-Caspian railway, leaving Uzbekistan behind, again crossing the dreaded Amu Darya river, and on into Turkmenistan, past Merv and finally reaching the border city of Ashkhabad, where they waited six weeks for official permission to leave the Soviet Union.

Janina has little recollection of this particular time, only that she was in hospital for “several months” and that a Polish priest visited her and told her that Romka had died. Sometimes she thinks he said, “the previous day.” She cannot remember where this hospital was, just that it was in “Russia” and was being run by “the Polish.”

The Polish graves register for Persia (now Iran) does not have a record of Romka, so she almost certainly died somewhere within the Soviet Union, either in Uzbekistan or in Turkmenistan.

On arrival in Ashkhabad, the critically ill children were admitted to the temporary Polish army hospital. Romka may have been admitted to the same hospital as Janina five months earlier. Romka probably died between April and August 1942, most probably in Turkmenistan. She was 16 or 17.

In fact they weren’t going to take me to Persia at all as I was not expected to survive the journey. However, a staff member whose daughter was my close friend took personal responsibility for me and refused to let me be left behind.

Maria Tarasiewicz: “We all lived for the day of our departure from the Soviet Union. It finally came in mid-October. We were elated on hearing the news. At last, after the British Consul's intervention, the Russians agreed to allow us to leave for Persia. To our original group of orphans from Kermine others were added at Ashkhabad with their staff personnel, so our numbers were substantially increased. As soon as the permission to leave was granted we organised our departure, replenished with medical supplies and army food rations donated by the Polish army authorities. Luckily, my brother Alek was discharged from hospital just in time, but many children and adults remained in hospital. Some of them were later able to join us in Meshed, while others died or remained ill in the Soviet Union.” 44

The total number of civilians in this departing convoy was approximately 640 children and 18 guardians.

When we left Ashkhabad we went over the mountains into Persia. I remember the road being very scary, but not much else about the journey.

Halina Fladrzyńska: “The journey to Persia was dreadful (two days, 250 kilometres). The roads were high in the mountains and were dangerously narrow, rocky and very winding. (The Koppeh Dagh, also known as the Turkmen-Khorasan Mountain Range.) We were hoping there would be no oncoming traffic during our trip as there was no room for vehicles to pass one another. The danger of the wheels slipping on the gravel, and the vehicle crashing hundreds of metres down to the bottom of the mountains, was very possible. I noticed the scenery both below and high above us was beautiful, however our minds were directed towards the city (Meshed) we were heading for, hoping we would get there safely.” 45

After two and a half years in the Soviet Union I was finally free.

Telesfor Sobierajski: “How and when I don’t remember, but for us it was a wondrous miracle that we were to quit this damned land to which for centuries our compatriots had been sent as slaves and where their millions of sacrifices lay in millions of graves…” 46

It is now estimated that barely 115,000 Poles were able to leave the Soviet Union before the border closed. Most crossed the Caspian Sea, 400 kilometres from Krasnovodsk in Turkmenistan to Pahlevi in Persia. This voyage was made in cargo ships, people tightly packed together, minimal food or water and sick and emaciated people openly suffering with dysentery.

About 1,900 civilians and 700 army personnel took the same overland route as Janina. The remainder of the surviving deported Poles of 1939-1941 remained trapped within the Soviet Union, and made unwilling citizens.

Bronislawa Bielińska: “We did not realise what immense good fortune had befallen us. Only much later, after many years, did we fully appreciate that we really were the chosen ones…” 47

I was like a skeleton and was very ill but eventually I recovered. I was 14 years old and weighed just 25 kilograms.

Evidence surfaced 65 years later to prove that Janina was actually then 16 years old. This discrepancy was probably a consequence of her father providing false birth dates to the orphanage in Kermine, making her three years younger than she actually was, almost certainly done to ensure that both Janina and older sister Romka satisfied the age limit for the orphanage.

Later there was some attempt to correct her age. Authorities in Persia made an adjustment for one year, to 1927. In 2007 the real age discrepancy was revealed when Janina was conferred her Polish citizenship and the accompanying documentation gave her true birth date, June 1925.

Soon after arriving in Meshed I was taken to an American hospital where I stayed for many months.

In early December 1942 some 250 of the travelling orphanage continued their journey, leaving Janina behind as unfit for further travel. In their “long convoy of canvas-covered army trucks” they departed Meshed, went south to Zahedan and, leaving Persia behind, turned west into Northwest India. The convoy travelled on through Nok Kundi, eventually reaching the Northwest Indian railhead. A six-day rail journey to Karachi followed and finally a few days by ship across the Gulf of Kutch to their final destination, Jamnagar in the Gujarat state of India.

That Christmas in hospital we were visited by Father Christmas. He gave me a present, an autograph book. I still have this book and will treasure it for the rest of my life. In fact other than a photo or two this book is the only memento I have from Meshed. The inscriptions are from friends I made in hospital and later at the orphanage in Meshed, and later again in Teheran and Isfahan. Also some inscriptions are from the staff who took such wonderful care of us.

These days it is difficult for me to remember many of the people who inscribed my book as it was so long ago, but some I do remember. For example, Lillian who used to teach me English. I think she was Syrian. She worked in the hospital but I can’t remember whether she was a nurse. There was a nurse named Katherine Mourada, possibly also Syrian. And Bernice Cochran, I think she was a doctor. Then there was Sister Celine from the Meshed orphanage. She was our teacher of religion. There are a couple of inscriptions with drawings from a friend who was a very good artist, Lodzia Leszka. Also from Meshed orphanage were Teresa Wiszowata and Zofia Pleciak who later came to New Zealand with me. In fact, Zofia’s family was from osada Hallerowo which was next to our osada, and our families had been in the same labour camp.

After seven months in hospital, Janina was released to the Polish orphanage in Meshed.

From Meshed I was sent to Teheran. While I was there I met a lady who knew my family from Poland. She had also been in the labour camp with us. She told me my brother Bogdan was alive and in the Polish Youth Army (junaki) with her son Edward. They were in Egypt. She offered to enclose a letter to Bogdan from me in her next mail to her son. This was how I found my brother.

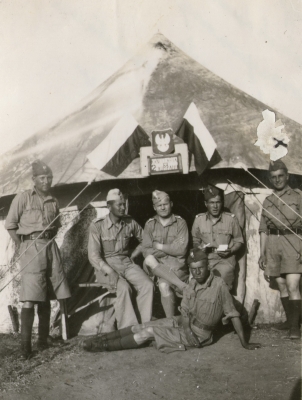

Bogdan Marchewa in the uniform of the Polish Youth Army, known as the junaki, in October 1945 and probably in Egypt.

After a few weeks in Teheran I was sent to a children’s home in Isfahan. Isfahan was a wonderful place. The orphanages were called homes and our home was set in the most beautiful garden surrounded by a high wall. I think it was one of the Shah’s palaces. Life in Isfahan was very happy and everyone was so kind. I stayed there for until we left for New Zealand in September 1944.

Janina recalled the figs and pomegranates being “so lovely, really juicy and sweet.”

I have wonderful memories of Persia and the kindness of the Persian people but after a little over two years on Persian soil it was time for us to move on.

Despite being well-settled in Persia the threat from the Soviet Union continued, especially when the Soviets occupied northern Persia.

“There was constant fear of the possibility that the remnants who escaped Russia would be returned there. This dreaded thought was always on their minds, sapping the people's confidence. They were afraid to even talk in public about their past experiences.” 48

Their concern heightened as the Polish army went to war. “The army’s departure was keenly felt by all Polish refugees. The army was closest to their hearts and was their devoted guardian, particularly of the children, under whose protective umbrella they felt safe.” There was now pressing need to leave Persia and “seek another shelter for the civilians, somewhere else in the free world.” 49

From Isfahan we were taken to Ahvaz and then to Basra where we were put on a British merchant ship and sailed for Bombay.

They departed 27 September 1944. They departed from the port of Khorramshahr to the east of Basra on 4 October 1944.

They started their journey with a two-day, 545-kilometre convoy of buses and army trucks northwards to Arak (Sultanabad) and boarded a night train for a tortuous ride west through the Zagros Mountains to Ahvaz. In Ahvaz, surrounded by desert and one of the hottest places on earth, they spent six days in a transit camp in 40°C plus temperatures before finally taking their leave of Persia.

The children often attribute Basra (in British Iraq) as having been their port of departure but they left Persia from the ancient river port, Khorramshahr. They boarded the sontay, a dirty French steamer captured by the British, that moved “slowly and carefully” through the Shatt al-Arab and out into the Persian Gulf.

After about a week we reached Bombay. There we were transferred to the American troopship general randall and we sailed for New Zealand.

The children arrived in Bombay on 10 October 1944 and after four days transferred to the general randall, launched on 30 January the same year with a 5,142-troop capacity. They departed the following day for Melbourne in convoy with a sistership and four destroyers. Wearing life jackets was compulsory. The ship zigzagged and changed direction “every eight minutes” under constant threat of attack from Japanese submarines. They awoke one night to a terrific jolt, possibly thanks to a glancing blow from a torpedo.50

“The soldiers said the children’s prayers had saved us.”

Janina recalled the Mass afterwards in which they were given details of the incident. From Melbourne and without escort, the general randall sailed on across the Tasman Sea to Wellington.

Late in the afternoon of 31st October 1944 we entered Wellington Harbour, 733 Polish children and about 100 adult supervisors.

Our first night in New Zealand was spent on the ship and the following day we were taken to the Wellington Railway Station. That was amazing. We were greeted by a huge crowd of children waving Polish and New Zealand flags. We travelled by train to Pahiatua and along the way we saw so many people, mainly children, waving flags.

Some of these New Zealand children recalled this as being the longest train that they had ever seen. The weekly news on 8 November 1944 reported the event within the contingencies of wartime censorship and associated propaganda, accrediting the plight of the Polish children to German rather than Soviet hands and reducing their universally traumatic experience in the Soviet Union to a term of “temporary asylum:”

“After being driven from their homes by the German invasion to temporary asylum in Russia and Persia, a party of 838 Poles have arrived in New Zealand to form a small colony at Pahiatua…”

This falsity of reporting had a profound effect on many of the Polish children as they struggled to adapt to a new life in New Zealand, denied any understanding or general acceptance by the New Zealand public of the fate they had suffered at the hands of the Soviet Union.

We had another huge welcome in Palmerston North and we arrived in Pahiatua shortly after. Our second night in New Zealand was spent in our new home, the Polish Children’s Camp in Pahiatua.

_______________

I was on that list going to New Zealand. I never even knew what New Zealand looked like or whatever. We were told first—you’ll be laughing at that—but we were told first that New Zealand is a beautiful country but there is still a lot of wildness in it, and the black eat the white. Yeah, we were told that.

Lonia: It must have been quite scary.

It was, we were crying. We didn’t want to go but they said, “No no, you’ll be okay. Lots of supervisors will go with you, you’ll be okay.” But that was really scary coming at first…

Coming to New Zealand was the greatest experience of my life. I’d never seen anything like it. New Zealand looked like a fairyland from the boat when we were first approaching the land. It was in the afternoon, a sunny afternoon. New Zealanders later on told us that when we came to New Zealand we brought the sunshine with us. The day was so beautiful, the sky so blue, and the New Zealand houses on the hills looked so wonderful. I’d never seen anything like it.

In the camp I acquired another autograph book. I think this was also a Christmas present. The inscriptions in the book are from my friends in the camp. We had all shared a similar fate so were very close, like one big family.

In Pahiaua some of the older girls wrote to the young men in the junaki, the thousands of teenagers looked after and schooled by the Polish army in the Middle East. Bronek, far right, who wrote to Janina, inscribed this photograph: “In such housing we live often. This photo shows the holiday of 3 May 1942. Bronek 10 September 1945.” This correspondence “fizzled” but Janina kept up a penpal relationship with his sister. She forgot their surname.

Janina in Girl Guide uniform in Pahiatua, circa 1945. She inscribed: “For my dear brother I am sending this photograph, sister Nusia.” Bogdan returned the photograph to Janina when they reunited 40 years later.

I spent three years in the camp during which time I finished my schooling. Then in 1948 my close friend Regina Mackiewicz and I went to work in Wakefield, Nelson, in the South Island. We worked in a sewing factory where I was taught to make men’s trousers. Regina and I boarded with the owner’s brother and his family. After 18 months we moved to Wellington.

A few years later I met my future husband, Antos (Antoni) Sarniak. He was from Częstochowa in Poland and before the war he had been working as an apprentice saddler for his brother.

In 1939 when Germany invaded Poland the army needed saddlers so Antos volunteered his services, standing in replacement for his older married brother. He was in the 27th Infantry Regiment. He had only just turned 17 and was captured during the first days of the war (on 9 September 1939). He spent the remainder of the war in a German POW camp (Stalag 6A, Hemmer, in Germany). After being liberated he joined the Occupation Forces in the British sector in Hamburg.

Antos Sarniak in Polish army uniform after liberation.

Here with “mates and cat” Antos Sarniak, on the far left, became a chef for the Occupation Forces in post-war Hamburg. He had two passages available to him and decided on the one to New Zealand because it was “as far from Europe as possible.”

Antos Sarniak was among 377 Poles, including 142 single men, who arrived as Displaced Persons via Bremerhaven in Germany with the hellenic prince in Wellington on 18 October 1950.

Janina and Antos Sarniak at a friend's wedding near the time of their own.

Antos and I married on 29 October 1955 and we settled in Wellington.

To the very lucky bridegroom

And the very lovely bride

The very best of wishes

As you start out, side by side

(Saved wedding card 1955)

Our two daughters Lonia (Leontyna) and Dorotka (Dorothy) were born in Wellington. They learnt Polish as their first language. In 1963 I developed tuberculosis and spent six months in Ewart Hospital in Wellington. The children were placed in the Home of Compassion orphanage in Island Bay. We were advised to leave our damp house as living there was too risky for my health. So we left Wellington and moved to Levin for the next 22 years.

I came to Levin today with happiness.

(Diary entry by Lonia, 12 Dec 1964, aged 7)

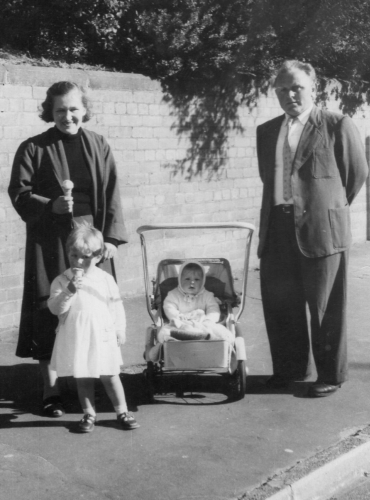

The Sarniak family in Wellington circa 1960. Dorotka is in the pram and Lonia has the ice-cream.

Janina and Antos outside their Levin home.

Janina and Antos at a function circa 1978 with their younger daughter, Dorotka.

My husband and I then moved to Papakura for nearly two years. Then we moved to Wanganui, our final destination. In March 1993 Antos was diagnosed with cancer. He passed away four months later on 3rd July 1993.

I still live in my own home in Wanganui and hope to spend the rest of my days here. My older daughter Lonia and partner Stephen live near me in Wanganui, and my younger daughter Dorotka and husband Bruce live in the South Island.

Lonia: Looking back, can you recall how some of these experiences made you feel?

When my mother died my world fell apart. I was very close to Mum and loved her with all my heart. I loved my father too very much, but I had a very special bond with my mother. Even though we were so desperately hungry and in rags our family still had each other so we had hope. Now Mum was gone everything changed.

When I went into the orphanage in Kermine I felt like my life had ended. I was so desperately unhappy. I cried whenever anyone spoke to me, especially if they sounded even a bit rough. The people were very kind but I felt so alone. I didn’t know where my brother and sister were, or even if they were alive.

Even in New Zealand part of me felt so miserable and unhappy and I cried a lot. On the one hand I was excited about coming here and loved the Pahiatua camp. It was my home. I had wonderful friends and we were like a family. Everyone was so kind and I was very happy there. But another part of me found it very lonely being completely alone. A lot of the children did have brothers or sisters in the camp but some of us had no family at all with us and that was really hard. And of course there were some children who were the only survivors from their families.

I knew that families were being reunited so I wrote to the authorities to see if my brother could come to New Zealand. At the time he was with the Polish Youth Army in Egypt and wanted to join me in New Zealand. I never received a reply so thought he wasn’t allowed to come. This completely devastated me as I couldn’t understand why he couldn’t come here. Many years later after I got married, my husband made some enquiries about why Bogdan wasn’t granted a visa and was told there was no reason why he shouldn’t have got one. They had no record of my application. Who knows what happened? Maybe my letter got lost in the post. They were now willing to grant him a visa but by now he was settled in England so he wasn’t keen to emigrate.

Bogdan Marchewa in the UK.

I finally saw my brother again in 1985 when he came to visit me in New Zealand. That was so wonderful but I know I will never see him again. He is in his mid-seventies, but is now blind and unable to walk without a walking frame. And I also have health problems so neither of us will ever be able to visit each other again. But I’ll never forget how wonderful it was to see my brother again after 43 years.51

Lonia: “Bogdan was a lovely, gentle man. He never married. He just wanted to live a simple life. He had what sounded like a Welsh accent and he wanted to go down to the pub each day, just for a beer and the company. His Polishness was largely gone, probably because he had been taken into an English family soon after the war and would have stopped speaking Polish and ceased to have exposure to the Polish culture. He didn’t talk about the past. I could see the tears swelling up when anything was said. I think Mum and Bogdan shared just a few brief exchanges about the war. That was all. I had so much I wanted to ask him but it was just not possible.”

Lonia with her mother commemorating the 60th anniversary of the 733 Polish children and their 105 adult caregivers arriving in New Zealand on 31 October 1994. This photograph appeared in the dominion post on 24 October 2004.

There was nothing for me to go back to so I have never returned to Poland.