Adam Piotrzkiewicz

Adam Piotrzkiewicz was standing at the edge of a crowd at St Bernadette’s Polish parish hall in Mt Wellington, Auckland, when I first met him in November 2013.

We were at the same celebration of the signing of diplomatic relations between Poland and Samoa. He seemed approachable. I was drawn to someone who looked as if they had lived a full life. We talked, and he agreed to allow me to interview him for this website—after I managed to convince him that having no children was no reason he should not share his history.

During the first of several conversations at his home in Auckland in 2014, it became clear that his story was unlike any other I had heard during my previous research into what happened to Poles in eastern Poland after the German invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939, and the subsequent Russian invasion of eastern Poland 16 days later.

The Soviet NKVD’s mass forced-removals of entire Polish communities to northern Russia and Siberia in 1940 and 1941 did not directly affect the Piotrzkiewicz family living in Lwów, yet they suffered in other ways during their city’s Nazi and Soviet occupations. The NKVD arrested Pan Adam’s mother and sent her to far eastern USSR when he was 13. Barely a year later, Germans invading a second time killed his father. An aunt and uncle in a nearby town took in his only brother, leaving the older Adam moving from relative to relative.

Pan Adam looked back on his life with such humour, honesty and self-deprecation, that I looked forward to our meetings and reviews, and to learning more about this quiet man. I listened back to the recordings, humbled by the patient way he answered even the silliest of my questions. Despite the many dark memories, the transcriptions are studded with “chuckles” and “laughs” as he recalled the ironies.

Adam Piotrzkiewicz died at his home at the Little Sisters of the Poor in Auckland on 24 December 2019, on the day that completed 47 years of his living in New Zealand. He may have had no children, but, judging by the number of people at his funeral, it was clear that he left many friends of all ages.

My appreciation and thanks to Pan Adam. I am glad I got to know him—just a bit.

(Specific historical dates are available in the military timeline section of this page.)

—Basia Scrivens

SURVIVING ON THE EDGE OF A CITY AT WAR

by Barbara Scrivens

Adam Piotrzkiewicz never found out why Russians arrested his mother, Maria, in August 1940. She received a five-year prison sentence to be served more than 9,500 kilometres away from their home in Lwów, Poland.

Adam, then 13, suspects his mother must have “said something” to annoy the Soviet authorities whose troops occupied Lwów after their invasion of Poland on 17 September 1939. The largest city in south-eastern Poland had protected itself “relatively well” from the German invasion that had started on the western, northern and southern borders of Poland on 1 September 1939. Even though many of the regular Polish troops usually based in the city were fighting the Germans in other parts of Poland, the Lwowiacy did not give the Russians the easy access they were expecting.

Lwów was then about 170 kilometres west of the Polish-USSR border. Until the Russian troops reached the city, they drove almost unhindered through the countryside between the border and Lwów. The main road east from Lwów ran through Złoczów to Tarnopol in Poland, and linked Poland directly to Kiev and Odessa in the Soviet Union.

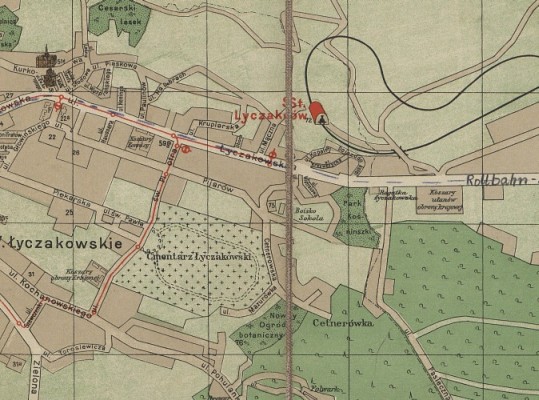

Trenches at least five metres wide and “very deep” stopped the Russian tanks around 22 September 1939. Adam recalled how Polish troops opened fire on the Russian tanks, cavalry and infantry as they approached along Łyczakowska Street. He lived close to that main road, about 250 metres from the city’s official eastern boundary, and fewer than 500 metres from the barracks used by the Czternasty Pułk Ułanów (Fourteenth Lancers Regiment) on the same road.

The unexpected Polish defence in Lwów seemed to fluster the Russian commanders, under orders to arrive for a planned meeting of Soviet and German troops and their commanders on a new artificial border dividing eastern and western Poland, which the Soviets and Germans created a week before the German invasion.

“The Russians were about two or three days late, because they couldn’t get through Lwów.”

In the end, it was Lwów’s mayor who gave up the fight.

“The Russians went under a white flag to the Government House in Lwów and the president of the city [the mayor] signed the surrender. He let the city go. The Russians went back to their positions but the Poles were still shooting at them because they didn’t know about the surrender. The [city] president put the white flag on the top of the government building, but you couldn’t see it.

“Some of the troops dropped their guns and went home and the Russians came in but first the ditches had to be filled.”

Some of the Lwowiacy, forced to help the new invaders, buried their arms and ammunition in the ditches rather than have them confiscated, but Adam remembers seeing local students collecting what they could.

…whole families began to disappear, to Siberia he heard, and all the time arrests like that of his mother on trumped-up charges were a matter of course.

A year after that, the city’s Polish population had become used to the “continual arrests” of their countrymen. Adam had seen the Polish populace visibly diminishing. Able-bodied men like his father, left to join the Polish army immediately before and after the German invasion. After the Russians arrived, whole families began to disappear—to Siberia, he heard—and arrests like that of his mother on trumped-up charges became a matter of course.

Adam remembers a particular day when his teacher, taking roll-call in class, repeatedly called out the name of an absent boy. Another boy stood up and said, “Oh, they were taken to Russia last night.” The teacher hushed him, saying, “Sit down and don’t comment.”

The children “knew quite well” what was happening in their city, and ignored their teacher when he urged them not to sing a Polish version of a Russian socialist revolutionary anthem, the Międzynarodówka (Internationale). The changed chorus matched the situation in Lwów: Bój to będzie ostatni krwawy skończy się trud, gdy Moskal ostatnio opuści miasto Lwów. (Take heed this will be the last bloody end to the trouble when the Russians leave Lwów or, as Adam explains, “We said we would be buried, that the fighting would only finish when the last Russian left Lwów.”) Little did he know then how the retreating Russian soldiers would affect him personally.

“The teacher, all the teachers, nearly dropped dead when they heard us sing!”

The adults had reason to be wary. The Russians seemed to be systematically exchanging Lwów’s Polish population with imported Russian families who occupied emptied houses.

“They brought in teachers. They brought in special police, families of Russian soldiers and officers and straight away they said, ‘It’s our land now.’”

One of the few certainties was that their disappearance would be early in the morning, one o’clock favoured by the oppressors.

“Everybody was packed, suitcases ready” because the remaining Poles never knew whether they might be forced to ‘visit Siberia.’ Sometimes the Russians rounding up the families told them to take all they could, including food, yet other families were not allowed to take much at all. One of the few certainties was that their disappearance would be early in the morning, one o’clock favoured by the oppressors.

“People sleep, but they don’t sleep that hard that they don’t hear neighbours being taken away…”

Unlike the distances between farmhouses in rural areas, Lwów was a bustling city of more than 300,000, and with many multi-storeyed apartment blocks. Shared walls—some thinner than others—allowed neighbours to hear the Russian soldiers’ shouts to occupants on the other side to “get ready, quick, quick, quick.” Adam remembers how those rounded up sometimes waited for several days in wagons at the main railway station before disappearing towards the Russian border.

“Sometimes someone walked past and heard them but what could they do? People tried to live carefully.”

_______________

Even before the Russians invaded, Lwów’s shops were empty.

“The day after the war started, there was nothing in the shops… in Poland?… where there was plenty of food? Shelves that were full—the next day, nothing. I couldn’t believe it. There was a black market straight away. The president miasta [mayor] ordered the bakeries to bake bread.”

Adam could not fathom the city shopkeepers’ reasoning for trying to profit from the war. They could have been shot for black-market trading.

“Once the Russians took over, there was nothing in the shops for six months.”

Queues started forming outside shops that sold bread. Adam remembers a time soon after the war started when his mother sent him and his brother, Wacław, then 10, to join the queue. Bombs started falling and Adam went home but Wacław refused to leave.

“My mother asked where my brother was and when I told her he was still sitting in the doorway of the shop, waiting, she ran to fetch him.”

That time, the bombing interfered with the bread delivery but while the Poles were still in charge in Lwów, bakers generally obeyed the mayor’s bake order.

“Once the Russians took over, there was nothing in the shops for six months. The bread, yes it came, but you did not know which shop it would be in—maybe only one shop in the whole city.”

The baker received orders to make deliveries to specific shops, seemingly chosen at random by the Russian authorities. Lwowiacy learnt that a bread shop’s existence did not guarantee delivery. When people in queues saw the baker with his delivery horse and covered bread cart by-passing the shop they were waiting to enter, they would often run after him but “the city is big…”

“Quite a few people got a few months’ jail for saying there was no bread that day, which of course, there wasn’t. He or she was arrested and in court the judge would ask the NKVD [People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs, the Soviet secret police] policeman if there was bread and the policeman would say there was indeed a shop that had bread.”

Adam remembers people exchanging furniture for bags of potatoes. No one blamed the farmers—even if they had roubles, there was nothing in the shops for them to buy.

About five or six weeks into their occupation, the Russians changed the monetary system. Adam remembers people being paid in złoty for a week’s work on a Saturday just hours before roubles replaced the currency. Polish savings became almost worthless as the new Russian ‘banks’ refused to exchange what they considered to be large amounts of złoty.

For the first six months of the Russian occupation, the Piotrzkiewicz family relied on food brought in by neighbouring farmers, who arrived by horse and cart to trade. They did not want money and Adam remembers people exchanging furniture for bags of potatoes. No one blamed the farmers—even if they had roubles, there was nothing in the shops for them to buy. After six months the Russians brought in food and clothing from Russia and the queues became a way of life.

“People used to stay in the queues. Something was supposed to come in from Russia, so they stood in the queue day and night.”

A signed slip from school entitled Adam to a pair of shoes, which soon fell apart. His father received a pair of Russian shoes because he had an approved job. They lasted four weeks and he sewed them together with wire.

Shoddy workmanship became known as “the norm.” Russian employees under the Stalinist system did not have the incentive to produce anything but a certain amount of daily output, the quality of which seemed irrelevant.

_______________

It did not surprise Adam that his forthright mother got into trouble for speaking her mind. With his father at ‘work’ she spent long hours in those queues—enough time for an infiltrator to overhear an unrestrained comment.

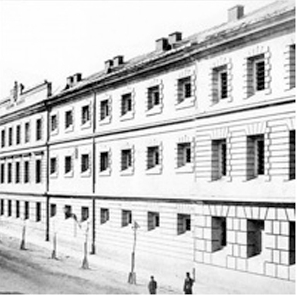

The courthouse was near the family home in Ulica Kopalna (Quarry Street). Adam, his father, Zygmunt, and Wacław witnessed Maria Piotrzkiewicz receiving her sentence. She waited for her fate at the Brygidki Prison, pictured here,1 in the centre of the city. The prison started life as a Bridgettine convent and changed functions during the Austrian partitioning of Poland in the late 1700s. From then on, its reputation became one linked with death and massacre of prisoners.

“My father was just looking,” said Adam of the day they watched his mother in court.

Maria Piotrzkiewicz was born in 1904 in Bóbrka, about 25 kilometres south-east of Lwów. She told her husband and sons in letters from Siberia that she had travelled for three months: Goods trains with covered wagons took her from prison to prison. Sometimes she stayed in a prison for a few days, sometimes weeks, until she reached her destination near Khabarovsk, close to China’s eastern border with Russia, and only 400 kilometres from the Sea of Japan and 750 kilometres north-east of Vladivostok.

“It was as far away as you could get in Russia.”

Adam assumed she had died after her letters stopped. He had no reason to blame the postal service:

“The Russian post was the best in the world. She wrote a letter. When we sent a letter back, she would turn it around and send one back again. Even if it didn’t have an envelope, even if it was written on a piece of paper, brown paper even, if you wrote an address with a return address and no stamp, it went, even if there were just a few words on it. When it came to Lwów, we paid for it. It was good that way.

“They knew they couldn’t cut as much as the NKVD wanted so they just moved wood from one stack to another… and got fed.”

“She wrote that she was starving and asked us to send her dried bread and smalec (spreadable fat). They didn’t feed people there. If you didn’t do the work—the norm—you didn’t get meals, just the soup, and she was cutting trees in short pieces and putting them in a stack…

“The men were smart. They knew they couldn’t cut as much as the NKVD wanted so they just moved wood from one stack to another farther away and so they did ‘the norm’ and got fed. They probably cut a third or half, but the rest, they carried from one stack to the next. It was done like that everywhere in Russia. Production is sky high, but there is nothing there.”

_______________

Adam remembered that his father “wasn’t very good” at looking after the three of them after his mother left, but that his paternal aunt and uncle helped, and they had enough to eat. His paternal grandparents had died in the 1918 flu epidemic, leaving five children, of whom Zygmunt was “third or fourth.” Adam has little memory of his maternal grandparents in Bóbrka, as there was seldom a good enough reason to make the long journey on foot. Leaving Lwów during the occupation was not an option, as it required NKVD permission and papers, and, after what happened to Maria, the rest of the family preferred not to draw attention to themselves.

Zygmunt Piotrzkiewicz was born in 1903, in Mikołajów, about 36 kilometres south of Lwów towards Stryj. He served in the Polish artillery in 1922 and had been a member of the Home Army. He enlisted again in 1939 but saw only a short stint in active service. He returned home about six weeks later, having escaped as a prisoner of war. Adam did not know what regiment he joined.

“Not that I don’t remember. He didn’t know himself where he was going. You go to the depot, you put your name down, they call you and give you a ticket to go to the depot by rail and get a uniform. The farmers used to bring their carts and horses into the town for the army to use, hundreds of horses and hundreds of carts. The farmers used to kiss their horses and went to get mobilised themselves.”

On the day Zygmunt left for the army, he arranged with Maria and Adam to meet him at the main railway station, as he wanted to say goodbye to friends and took a longer route. The station, to the west of the city, was already “quite a walk” for his wife and son.

It took… the sight of a full tramcar, bombed, for Maria to concede the danger and take Adam with her to the bomb shelter…

About halfway there Maria and Adam approached what Maria believed was a Polish anti-aircraft artillery practice zone: “Quite a lot of shooting,” and a policeman shouting at them to get into the nearby bomb shelters. Maria refused to countenance German bombers, telling the police officer “it couldn’t be” because her husband was still in the city.

Even when they saw glass lying on the road from surrounding buildings, Maria blamed “nasty” students.

It took turning the corner and seeing enemy planes peppering the railway station ahead—and the sight of a full tramcar, bombed—for Maria to concede the danger and take Adam with her to the bomb shelter. They stayed until another bomb hit the building next door. She got up saying, “Let’s go home, it’s not safe here.” She probably had a point. Lwów’s bomb-shelters were flimsy compared to the bunkers Adam saw later in Norway and Italy.

Unlike his wife, Zygmunt did turn back when the bombs started falling. As a member of the Home Army, he had participated in civil defence practices held before the war and knew these bombs were not the tear-gas canisters exploded during drills to train citizens and university students.

Maria and Adam met Zygmunt on the way home and, after the bombing stopped, the three turned around and went back to see him off at the unscathed railway station.

Six weeks later, his father walked into Adam’s bedroom again, still dressed in his Polish army uniform. Adam could not understand how he had crossed the border dressed like that, but his father told him the guards did not seem interested in him.

The only thing that made sense to Adam was that the Russians mistook his father for a Ukrainian. In the 1931 Polish census 58 percent of Lwów’s population declared Polish as their “mother tongue,” 34 percent as Ukrainian and eight percent Yiddish.

For several years, rural villages near the city, like other areas along the eastern Polish border with the Ukraine, had problems with militant Ukrainians intent on killing Poles. Not all Ukrainians felt the same but occasionally a group gathered with murderous intent, like the one Adam remembered being led to a neighbouring Polish village by a Ukrainian priest holding a cross. A phone call to the police station summoning the nearest army unit in Lwów defused that particular incident.

Pre-war Poles were used to protecting themselves from certain Ukrainian factions, difficult to identify if members spoke Polish, which is what Adam suspects had a role to play in the capture of his father’s unit on the road from Warsaw.

… even a genuine Pole in uniform was not above suspicion… as Germans parachuted spies dressed in Polish uniforms into Poland…

Zygmunt’s army unit had apparently received orders to take arms and horses and retreat to Lwów. As their transport travelled under cover of the woods, Ukrainians “jumped” them, took the horses and carts with rifles, machine guns and bayonets and told the Polish soldiers to “walk.” Without any way to protect themselves, the Polish soldiers were helpless when confronted by German soldiers.

“There were so many prisoners; they didn’t lead them on the roads. They used to lead them through the fields. They never fed anybody so the prisoners used to eat anything they could find growing on the way. There were a lot of wounded people, some on carts, some just walking and only one German soldier on a bicycle guarding them. He rode up and down the line of prisoners.

“After a day or two he rode away and never came back, so the prisoners just walked away… There were plenty of forests in Poland. My father walked all the way back to Lwów. It took him about three weeks. That’s what my father told us.”

In those early days of the war even a genuine Pole in uniform was not above suspicion from his fellow soldiers, as Germans parachuted spies dressed in Polish uniforms into Poland, and Polish orders were for them to be shot. If another Polish army unit had come across Zygmunt walking alone, soldiers would have checked his uniform for parachute marks and documentation. Adam’s father arrived home with a helmet, a gas mask and some books from an abandoned library.

Zygmunt knew the helmet and the gas mask would be useful in a new role with the Armia Krajowa (AK), the Polish underground.

“After being occupied for more than 120 years, the Poles thought very strongly about Poland. Not that Poland was an especially good living but we were again Poles in our own country. So as soon as the guns stopped firing, the Poles started getting together to build the Polish underground. My father went out and came back with a gun.”

His father knew Adam loved reading. Before the war, he enjoyed school and was inspired to learn so that he could read the books he was introduced to by the older brother of a friend of Wacław’s, who visited their home and read aloud stories such as w pustyni i w puszczy (In Desert and Wilderness) and ogniem i mieczem (With Fire and Sword) by Henryk Sienkiewicz.

The boys’ school entrance was on Łyczakowska Street about 50 metres from Adam’s home. The girls’ school, on the same property, had a separate entrance. Adam remembers the school’s name as Ziemorowicza, apparently after the writer and poet Bartłów Ziemorowicz (1620–1680) who had lived in Lwów.

Once the Russians occupied the city, girls and boys joined classes, and education became serious. School days lasted from 8am to 5pm and hours of homework expected. There were extra mathematics lessons and Adam remembered a teacher brought in from Moscow to teach them Russian and Ukrainian taking the “longest time” to realise her pupils were not doing their Russian homework.

Adam’s house did not need a number because it was the only one on the road. The quarry relating to the name of the street had closed before Adam was born. City officials favoured building a new suburban railway station over expanding the quarry and the remaining sandy banks became a playground for the children of the area.

“It was nice… just run and slide down.”

A map showing Kopalna Street directly south of the new railway icon. The city's eastern boundary line is seen running from the north of the railway station, through Łyczakowska Street, and leaving the Czternasty Pułk Ułanów barracks just outside. The Cmentarz Łyczakowski (cemetery) is to the south and the city centre with the Brygidki prison is off the map, to the west.2

Whatever Zygmunt did for the Polish underground, during the day he played the part of an ordinary citizen. Even though there was so little value in the Russian rouble—and little to purchase other than through the black market—not working meant arrest, so Zygmunt spent his days doing “the norm” at the local brickworks.

The Russian occupation of Lwów continued until late June 1941. On 22 June, German troops crossed the same demarcation line cutting Poland in half that the Russians had been hurrying towards in 1939. The Russians still in Lwów started retreating towards Moscow.

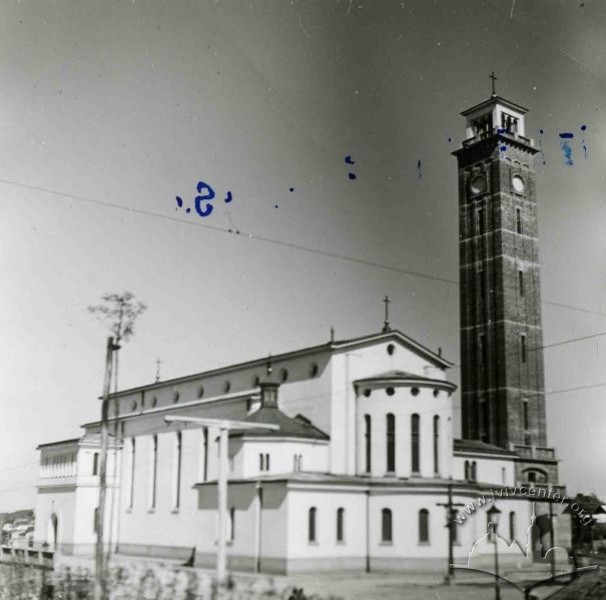

Adam later found out that two Germans wearing Russian uniforms infiltrated the Russian retreat lines. Armed with a substantial amount of weaponry, including anti-tank guns, they took over the tower next to the Church of Our Lady of Ostra Brama on Łyczakowska Street.

The church was new, a result of the expanding Catholic community in Lwów and had taken five years to build.

“The previous church, St Anthony’s, closer to the city, was old and dark and I didn’t like it. It got too small. I loved the new church. It had a huge tower to the side, with a proper four-sided gate, like the Ostra Brama in Wilno. It was on a hill and they built the tower so high and with thick walls and narrow windows so that it could be a fortress and lookout against the Russians.

“When the priest saw the Germans, he left. The German soldiers stayed in the tower for two days. For some reason, they started shooting.”

The Church of Our Lady of Ostra Brama on Łyczakowska Street, Lwów, is now known as the Protection of Our Lady Church, and the Ukrainian spelling of Łyczakowska is Lychakivska.3

“We lived very near the main road going east. My father heard the shooting and opened the door to see what it was all about. That was when he was shot. He was curious.”

Soon after the Germans killed Zygmunt, they shelled and destroyed the single house in Ulica Kopalna.

After Zygmunt’s funeral service, friends carried his coffin to the Łyczakówski cemetery. The mourners expected a prepared grave but found nowhere to intern him. They had forgotten they needed a death certificate before burial. The woman at the cemetery office told them that if they produced one the next day, they could bury him in what the woman described as a “big hole” due to be dug for the prisoners the Russians had killed. The next day a mass grave appeared next to the Austrian War Cemetery. Adam did not know who did the digging.

“They were bringing them the whole day from the three prisons, all naked, not well covered and you could see hands and legs sticking out.”

“The old lady said we should just put him in on the side of the hole and he would be ‘first’ and that’s what we did. We put him on the edge and covered him a bit, but not much, because it was a big, deep hole.”

Adam’s experience of putting his father into what was obviously to become a mass grave heightened his awareness of his father’s future burial companions. He then noticed the continual transport of corpses by horse and a flat-bed cart.

“They were bringing them the whole day from the three prisons, all naked, not well covered. You could see hands and legs sticking out. The idea was that the dead don’t talk, and if they weren’t dressed, you wouldn’t know who they were. The opinion was that they were Ukrainians, because the Russians didn’t want the Ukrainians fighting alongside the Germans.”

What made that particular time stick in Adam’s memory was not the callousness of the actions, nor the disrespect for the dead, nor the lack of feeling towards those civilians who had to transport or witness the transportation of the corpses. It was the fact that NKVD officers returned to the city after leaving in such a hurry a few days before.

“We were surprised when the NKVD came back because they liked to keep with their troops, to make sure the soldiers don’t run away.”

Knowing this NKVD policy, Adam believed there must have been a specific order to execute other prisoners and remove the evidence before retreating. Such a direct order explains why the NKVD completed the process in such a hurry.

The Cytadela… was established only as a means to subjugate the population.

A favoured place for executions was Lwów’s Cytadela (citadel) on a hill south of Kopernika Street in the centre of the city, seven city blocks from the Brygidki prison on Kazimierzowska Street. The Łąckiego prison on the intersection of Leona Sapiehy and Kopernika Streets was even closer to the citadel—only a city block away. The Polish army built a third prison, in the northern suburb of Zamarstynów, in the 1930s. The NKVD used it for political prisoners.

Lwowiacy well-knew the Cytadela, before the war a popular landmark within gardens. The Austrian army built it in the mid-1800s during the Austro-Hungarian occupation of Polish Galicia. According to Stanisław Kobielski, writing for the Institute of Lwów in Warsaw, it was established only as a means to subjugate the population.4

In 1941 the Cytadela lived up to its historical reputation:

“When the Austrians came, they put guns there to shoot over Lwów if necessary. Russians [in 1941] used to shoot Poles there every night, about 20 at a time. They’d walk them from the prison, mostly teachers and professors, guarding them tightly… It was a very hard time, it was difficult…”

He recalled that the NKVD left the prisons open after they retreated from Lwów for the second time. Those who ventured inside walked into a “sea of blood up to their ankles” and found remaining corpses with “stomachs opened and guts hanging out.”

As Germany advanced on Russia, Maria Piotrzkiewicz’s letters home stopped and shortly afterwards Adam and Wacław parted. His brother lived with his father’s eldest brother in Mikołajów and Adam stayed with an uncle in Lwów’s Pasieki suburb for six months, then with his aunt, and finally with a cousin.

Lwów settled into life under a different occupier. Schooling stopped and Adam helped his aunt by selling placki (potato pancakes) at the local market. When he sold one batch, she would make another. He was 17 when he found a way out—through an Austrian construction firm recruiting for labour in Norway. He remembers the company’s name as “Stein” (stone).

“Quite a few teachers signed on because they said that when the Russians returned, things would get worse and they would be taken to Russia.”

_______________

Adam went with about 35 others to the port city of Szczecin (then in eastern Germany) and by ship to Oslo. There the Poles, along with Austrians and Yugoslavians, built bunkers for the Norwegian Royal Family—or so they heard. There were two impressive bunkers, one in Oslo and one about 20 kilometres away in a mountain next to the Royal summer residence.

“They put water there, power, heating… It was painted inside, it was about four or five hundred metres deep.” Adam was disappointed not to stay in Norway, a welcome respite after the previous few years in Poland.

Once, a guard in German uniform asked him if he was a Pole. “I said yes, I’m from Lwów. He said he was from Poznań. He said he didn’t speak German but they weren’t allowed to talk in Polish, even among themselves.”

The young soldier told Adam of two Polish divisions in the German army in Norway. German military authorities seemed to know the Poles would not fight for them so they replaced two authentic German divisions in Norway with Poles and sent the Germans to the front.

… they were conceivably digging bunkers on the other side of the front where their fellow countrymen were fighting.

Adam’s information regarding the state of the war at that time had a German slant. He remembers hearing Hitler “shouting” over the radio.

“Before Christmas, they took half of us to Austria and the other half back to Poland. We didn’t do much in Austria. We used to clean the rubble from the bombings and then Stein got the job of building bunkers in Italy.”

Some of the Austrian workers had a map of Europe, so the Poles knew the whereabouts of the Italian front and their destination.

“It was Bologna. There were some sort of mountains there, not very big mountains, but mountains all the same. We had to cut the roads and make bunkers for the soldiers. There was usually an army engineer who would show us where to dig, so we were digging. Because we were near the front, we had uniforms. They called us ‘working battalions.’ We got paid, not on the hand—in a bank in Berlin—but we also got paid what the army got, one mark a day. You could always buy something.”

Others in his group found out that the Polish army was in Italy and that they were conceivably digging bunkers on the other side of the front where their fellow countrymen were fighting.

One day, Adam’s working group of about 30 was told to retreat but did so deliberately slower than the German soldiers. They dropped so far behind, they were overtaken by an American army unit. The Americans asked in English who they were. The Poles replied, “My Polacy, my Polacy.” (“We’re Polish, we’re Polish.”) The Americans understood enough to call a Polish lieutenant, who verified their nationality and arranged their transport to Allied lines.

_______________

Being among fellow Poles felt “unbelievable.” They were questioned in a tented camp. Most of the group went to infantry divisions because “all armies were short of infantry.” The Czwarty Pułk Artilerii Lekki (Fourth Light Artillery Regiment) accepted Adam and one other. More Polish soldiers in German uniforms arrived at the camp and the new recruits started training within the II Polish Army Corps.

Adam, right, poses with a friend, a few years older and with the surname Zapłata, soon after joining the Polish army.

Although the soldiers from the German units had had military training, Adam and his former digging companions had no knowledge of weapons. One thing the new Polish soldiers did not have to learn was marching.

“We marched all the time in school. In other countries they played football, in Polish schools, they marched!”

Adam remembers being so physically weak at the time, he could not lift the tail of an artillery gun.

“Two of us were working on it and couldn’t hook it. The driver came out and did it in one go.”

Here, Adam is third from the right in the back row. Names written on the back are: Heszek, Kolonowski, Stwiertnia, Zajztata, Piesik, Nawrocki, Smański and Męrzny.

Adam is the only one in the photograph from the German army’s ‘working battalions.’ He is unsure from which German units the others came.

“We didn’t talk about it. We didn’t ask.”

The battle for Bologna on 21 April 1945 was Adam’s first and the II Polish Army Corps’s last major battle in Italy. He remembers the two new brigades of Polish infantry that attacked Bologna being heavily supplemented by soldiers who had been forced into the German army, and who had escaped.

Lieutenant-General Władysław Anders, Commander of the II Polish Army Corps in Italy, had predicted this influx of Poles previously conscripted by the Germans. On 30 January 1944, prior to the Polish troops’ arrival in Italy, General Anders met with Supreme Allied Commander in the Mediterranean General Henry Maitland Wilson.

In his book an army in exile, General Anders explained the military situation at the time:

… the II American Army Corps took advantage of the success achieved by the French… got to within several hundred yards of Monte Cassino monastery, and part of its forces entered the town of Cassino from the north. The exhausted French and American units were then withdrawn and replaced by the New Zealand Army Corps.

Italy had become a challenge and General Maitland Wilson asked General Anders how the II Polish Army Corps could be reinforced in the event of similar heavy casualties.

I answered him, as I did all my colleagues, that reinforcements would join us from the front line. We had no country behind us to get our reserves from, but we knew that at the first news of Poles fighting on the Continent, all Poles, and, above all, those who had been conscripted by force to join the German army, would try to join us…

General Anders’ reassurance led to the II Polish Army Corps becoming a component of the British Eighth Army.5

… the Italians “decorated” the Poles for taking Bologna with minimal civilian casualties.

Adam remembered heavy military losses in the Bologna battle. With each brigade made up of three regiments, he estimated the new recruits numbered about 6,000. He remembered how the Italians “decorated” the Poles for taking Bologna with minimal civilian casualties, how he had looked forward to the push towards Germany, and how disappointed he was when the II Polish Army Corps was “put to rest” in Italy. Adam believed the Allies bowed to Stalin, who had not wanted the Poles involved in the liberation of Europe.

“The British and the Americans left Italy before the war finished because they were attacking [the Germans in] Europe from France. The Poles [in Italy] became much busier. The divisions of the New Zealand army that fought side by side with the Poles got an order to go to Trieste to remove the Yugoslav communists who had taken over that city. The New Zealanders were going very fast and they put the Polish army closer to Trieste at the time, but we weren’t needed. The New Zealanders had done it quite well.

“When the war was over, the Poles had to take care of everything in Italy, watching the trains, the transport, the army stores, the pipes of petrol and diesel going through Italy. Watching the PoWs was nearly a full-time job. There were even Ukrainian prisoners in German uniforms who had two divisions (one was SS Galicia), fighting the Russians in Tarnopol and Złoczów. All sorts of Ukrainian soldiers came to Italy, because they thought the Russians would kill them if went home. I don’t think they were fighting in Italy but still, they were prisoners.”

The remaining soldiers often posed for photographs.

Above, taken in Ravenna or Rimini, Adam is in the back row, third from left. “These are all Polish soldiers originally in the German army and they’re on the Polish side here.” Left, Adam in winter uniform in Ravenna. He remembered the city's 6th-century basilica.

_______________

The II Polish Army Corps transferred to the UK at the end of 1946. Whole regiments at a time loaded on troop ships, his ending up in Cirencester, an old Roman town in the Cotswolds. They received instructions to guard a former PoW camp that had held Germans.

Cirencester residents objected to a Polish armed guard at the camp gates. When British soldiers guarded the German prisoners, they did so within the camp boundary and were apparently not seen with rifles. The Poles followed their own military custom of guarding the outside perimeter, which affronted the town’s residents.

‘Why don’t you go back home?’ they said. ‘We fought for you,’ they said, ‘Why are you here?’

“They called the police and the army police, and asked why were there soldiers with rifles standing at the gates when even during the war, the British soldiers didn’t guard anything with a rifle.”

The spell in Cirencester did not last long.

“For one thing, they didn’t like us there. You see, it was ’46 and the war for them finished in ’45, so what were we doing still in uniform? In England? ‘Why don’t you go back home?’ they said. ‘We fought for you,’ they said, ‘Why are you here?’”

The visceral reactions of the locals led to the Polish soldiers being moved elsewhere. The same locals may not have understood that the Poles had fought for their own free homeland, and would have far-preferred to have been there.

The majority of the soldiers in the II Polish Army Corps had lost their homes in former eastern Poland, absorbed by the USSR in 1945. Between 1939 and 1941, Soviet soldiers had, at gunpoint, removed many of these men and their families from their homes, and interned them in Stalin’s forced-labour facilities. At the Teheran Conference in November-December 1943, Churchill and Roosevelt secretly assured Salin that the West would back his intention to keep the same portion of Poland that his troops had occupied under his 1939 pre-war deal with Hitler. Churchill and Roosevelt repeated their promise at the Yalta Conference of 4–11 February 1945 and their successors ratified it in Potsdam in August 1945.

The UK may not have been the Poles’ first choice of a post-war home but it was preferable to the probability of being again interred somewhere in the USSR, if they returned to post-war Poland (see Adam’s explanation below). Polish soldiers, and later their families too, occupied many of the recently vacated army barracks in England. These Polish Resettlement Camps developed strong communities separately nick-named “Little Poland” all over the UK.

After Cirencester, the Polish soldiers in Adam’s unit ‘guarded’ the old barrel-shaped Air Force barracks in Southend, ostensibly against squatters.

“We guarded day and night, walking. Well, you couldn’t guard much, because it’s miles, and one night I said to the officer, ‘Look, I don’t want to go at night to watch them, to watch the empty barracks. There’s lots of water tanks… I will fall down there and drown.’ So the officer said, ‘That’s all right but be quiet and don’t sleep in case the English come and check.’ So we were… we were watching.”

Potential squatters did not worry the men as much as their hunger. Their rations were “small, much smaller than in Italy,” sometimes a slice of bread a day, and their Polish warrant officer seemed too embarrassed to ask for more food. Adam and a few others managed to communicate their predicament with their English driver, who stole a couple of loaves of bread for them. Eventually one of the Polish soldiers approached the English authorities and told them they were starving. The lack of food had been an oversight and they were soon treated with pierogi (filled pasta), gołąbki (stuffed cabbage rolls) and kotlety (meat cutlets).

Adam spent a year in a barrack hospital near Dorchester, pictured here third from left, after being treated for complications from a burst eardrum when with the Fourth Light Artillery Regiment. It led to the loss of hearing in that ear.

In hospital he had “time to think” but did not contemplate trying to find out whether his mother or brother were still alive. He feared endangering their lives.

“When the Russians were in Poland in ’39, they used to arrest anybody who had relatives abroad. If you had a relative abroad, it was assumed you were ‘spying.’ The soldiers knew that, so nobody wrote to Poland enquiring about families or anything in case [the addressees] were taken to Russia. It was not only me, it was everyone.”

During the Russian occupation of Lwów, Adam’s uncle in America used to write to Zygmunt, occasionally sending “a few dollars,” and he had seen his father, while grateful for the contact and gift, afraid for his family.

“It was peculiar. They didn’t take everybody. Some of the soldiers, they just sent home when they returned from the army after the war, but some, they sent to Russia and they didn’t come back for five, six years.

“I came out of hospital in ’48 and one of the soldiers, still in uniform same as me, got an answer through the Red Cross about his family. They had been moved from the east of Poland to the west, to Szczecin, so I wrote to the Red Cross in Warsaw, sent some money in an envelope and asked about my brother and uncle. I didn’t ask for my mother.

“I got a letter back saying that my uncle was living in Szczecin and they gave me his address. I wrote to him and he said, ‘Your mother is here,’ and gave me her address. My mother had been looking for me for two years, and for my brother too.”

“My mother didn’t like it one bit that I didn’t look for her… I knew she was in Russia, dead maybe… If she were alive, where was she?”

Maria, still unafraid of the Soviet authorities in Poland, had written to newspapers and the Red Cross in London, Italy and Germany. It surprised Adam that she found no one who seemed to know his whereabouts from official army lists.

In contrast, Adam’s letters annoyed his Szczecin uncle because it led to the police “asking questions.”

“My mother didn’t like it one bit that I didn’t look for her… I knew she was in Russia, dead maybe… If she were alive, where was she? She took it hard that I was alive and not looking for her. I didn’t know I could ask the Red Cross for people coming out of Russia. My uncle didn’t know where my brother was.”

When they eventually met, Wacław—here aged about 18—was vague about what he had done since the brothers parted, and seemed to have spent the war years drifting from town to town. He had apparently returned to Lwów for a while, then moved to Śląsk, “getting lifts in cars and trucks.” Russians arrested him but he escaped.

After a family friend saw Wacław in Śląsk and told him that his mother was alive and in Szczecin, he found her and settled in the same city. He married, and named his children Leah and Zygmunt.

_______________

The prison near Khabarovsk released Maria as part of a July 1941 ‘amnesty’ agreement between Poland and the USSR. The German advance on Moscow at the time led Stalin to believe that the Polish people incarcerated in his forced-labour facilities and gulags would be useful as soldiers in Russia, and ‘allowed’ them to leave those facilities.

Being allowed to leave and being able to leave were two different things. Who knows what options Maria Piotrzkiewicz faced, so far away from anything and anyone she knew? Adam asked her why she did not join the Polish army. “We were a few women,” Maria said, and the others had urged her, “Don’t leave us, don’t leave us.”

To travel the thousands of kilometres to a Polish army may have been impossible to contemplate, and Maria had no certainty—even if she believed a Polish army was indeed forming—of its whereabouts. At some stage she moved to, and found a job in, an “industrial town,” possibly Khabarovsk. Unbeknown to either of her sons, she returned to communist-controlled Poland in 1946.

After their first contact, Maria and Adam corresponded for nine years before she received permission to travel outside Poland. Adam had by then settled in Scotland.

His mother could scarcely believe the availability of produce or the freedom people had in Scotland to make their own consumer choices.

“She didn’t talk, she just looked at everything in the shops… two, three butchers… you can pick your meat, whatever you like. She stood and she cried. When she was cooking something, she went to the shop and with something like 40 pence, asked for this and that, pointing to what she wanted, and the people gave it to her.”

The shopkeepers later told Adam what his mother had ‘bought’ and he settled the bills.

Adam visited Maria for the first time in Poland in 1959, reunited with Wacław, and met his sister-in-law. Adam was nervous visiting an unfamiliar Poland but went with a friend who had been before.

Twenty years after that first trip people were still queuing “half the night for meat.”

“It was strange. I went on a train and had to get off in Poznań. I was staring out of the window and my friend said, ‘You had better go, or you won’t get out.’ I nearly didn’t. All of a sudden all these people were pushing into the train. I wasn’t used to that. I had to get my suitcase through the window. Poland had changed.” Adam last visited Poland in 1979. Twenty years after that first trip people were still queuing “half the night for meat.”

Adam’s mother died in Szczecin on 15 February 1989 and his brother in 2005.

_______________

In 1948 Adam’s position as a former Polish soldier entitled him, under the Polish Resettlement Act, 1947, to some form of tertiary education. He decided to enrol in an agricultural course in Glasgow—his year in the hospital prevented him from taking advantage of a more academic route. On graduating from the agricultural course, a Pole offered him a job running a 200-acre farm. Adam turned it down after his first practical experience.

“We learned a lot, but we didn’t learn being a farmer. The practical was hard, especially digging potatoes, bending all day. I didn’t take to it.” Adam never did lose the influence of his city upbringing.

Above, Adam (middle back row) with some of his fellow students, taken on a trip to the Scottish east coast.

After six years in England, he returned to Scotland and found employment in Glasgow that “suited him much better” working for the High Street railway station specialising in transporting goods. He felt lucky following an agricultural college friend, Władysław Buczkowski, into a job, as Scotland was no longer the industrial power it had been during the war years when it produced tanks, locomotives, cars and trucks. With goods still primarily transported by rail, the High Street station retained its bustle.

Adam was content with second place to Władek who, through speed and bonuses, earned more than anybody else at the station. Life was good. Both young men married, Adam to Irish Christine and Władysław to Scottish May and it was a blow when after 10 years, Władek decided to migrate to Australia.

“… he had a British passport, but he was a Pole, and they didn’t want Poles… so he sat at one end in Immigration.”

“I missed him because he was a good friend. I didn’t need much help but he was there if I needed it.”

The Australian heat and flies did not suit May, and they were about to return to Scotland when they decided to visit New Zealand.

“Well, there was little bit of a problem because he had a British passport, but he was a Pole, and they didn’t want Poles [in New Zealand], so he sat at one end in Immigration. May was outside, waiting for him with the children. After two hours, they told him, ‘If you find a job, you can stay.’ He got a job next day.”

Władek and May returned to Scotland for a holiday and enthused to Adam and Christine about New Zealand’s weather, warm enough to grow oranges, and its plentiful job market. Władek also promised Adam initial accommodation. Adam weighed up the thought of leaving a secure pension and made the leap, arriving in Auckland with Christine on Christmas Day 1972. It had taken two years to collect the necessary papers because, although New Zealand’s immigration policy towards Poles seemed to have softened, Adam still had the impression “they did not want Poles.” The feeling came about when he needed to pass a medical examination, which his doctor described as akin to rigorous army exercises, while his Irish wife of the same age was not required to produce any kind of medical certificate.

Arriving during the peak holiday season did not put off Adam looking for a job and he landed “the best job I ever had” at the new zealand herald in Auckland's Queen Street. He worked as a general hand for nearly five years and appreciated the strong printing union, which “did quite a few good things” for employees. In those days, recruitment agents stood on the street offering jobs, apparently paid $5 for each worker they placed.

It did not take long for Adam to buy his first property. He took advantage of the New Zealand government’s housing scheme, which gifted first-time buyers with $16,000. His house in Henderson cost $22,500 in 1974 and his only regret is not buying another one in St Mary’s Bay because within a few months $12,000 houses sold for between $20,000 and $40,000.

Adam and Christine with their friend Marysia Jaśkiewicz at one of the Polish holiday functions.

Adam and Christine’s introduction to the local Polish community was a New Year’s dance, a week after they arrived, arranged by the local Poles, then numbering about 120. At that time, the Dom Polski (Polish House, a gathering place) was a residential building and they hired a hall.

Adam later volunteered to work at the Dom Polski, and helped ease the transition for some of the new immigrants who arrived regularly from Poland, and later from Africa.

Although he stopped working at the Polish church when it moved to Mount Wellington, he was always greeted warmly when he attended Polish Mass or any Polish functions.

The Polish government acknowledged Adam’s contribution to his country on 7 December 2017 when he and fellow veteran, Stanisław Szczepański received Polish Pro Patria medals. The award was established in 2011 and given for “Outstanding contributions in perpetuating the memory of the people and deeds in the struggle for Polish independence during World War II.”

At the ceremony for the presentation of Polish Pro Patria medals to Adam Piotrzkiewicz and Stanisław Szczepański, Polish Ambassador to New Zealand, Zbigniew Gniatkowski, is left and the Polish Honorary Consul in Auckland, Bogusław Nowak, right.

Adam’s health finally forced him to move into the frail-care section of his rest home, but until then, anyone who walked into his book-filled lounge, with the television on a world affairs channel, witnessed his retention of interest in people and politics.

Adam outside his apartment at the Little Sisters of the Poor in Auckland in 2014.

WW2 cost Adam his parents, his home, his schooling, his city, his country, and his hearing, but he clung to his intellect, wit, and thirst for knowledge.

Rest in peace, my friend.

© Barbara Scrivens, 2015

Updated January 2020.

APART FROM THE BRIGIDKI PRISON, THE OSTRA BRAMA CHURCH, AND THE LAST TWO, ALL PHOTOGRAPHS COME FROM THE PIOTRKIEWICZ COLLECTION. MARIAN SOSNA TOOK THE ONE AT THE PRO PATRIA CEREMONY AND BARBARA SCRIVENS THE LAST ONE.

THANKS TO THE NORTH AUCKLAND RESEARCH CENTRE IN THE TAKAPUNA LIBRARY FOR THE LOAN OF AUDIO RECORDING EQUIPMENT.

ENDNOTES:

- 1 - http://wikimapia.org/4912560/City-prison

- 2 - Map is a section of one from Mapywig. Home page for the English version is:

http://english.mapywig.org/viewpage.php?page_id=11 - 3 - Although this particular photograph is not the same as the one in the web page below, it has the watermark

of the same Centre for Urban History of East Central Europe:

http://www.lvivcenter.org/en/uid/picture/?pictureid=1761 - 4 - http://www.lwow.com.pl/rocznik/cytadela.html

- 5 - This quote and the one above: Anders, Lt-General W, CB, An Army in Exile, originally published in 1949. Reprinted by The Battery Press, Nashville, ISBN: 0-89839-043-5, 152–153.