Ann Kathleen née Jobson Jacques

Most of the stories on this website are about people with Polish backgrounds. This is not one of them.

This story is about an English woman who immigrated to New Zealand with her husband in 1928, and who settled in Palmerston North. There were some descendants of early Polish settlers in Palmerston North at the time, but there would have been no obvious reason for her to mix with any of them. (New Zealand spellings of some of those buried at Palmerston North cemeteries are: Lucinsky, Max, Ofsofski, Palenski, Rosanowski, Shapleski, Stobba, Wicki, and Wisniewski.)

This is a woman I would not have investigated if it had not been for researcher and writer Warren Elliott, who invited me to work with him during his research on his wider documentary project surrounding the Polish Army League.

Warren had found a link between Polish and New Zealand soldiers in the early stages of WW2. The Poles had escaped Poland with their units in 1939 and had fought alongside New Zealanders in the north African campaign of 1940–1943, years when Poland was occupied jointly by Germany and Russia, or later by Germany alone.

The Polish soldiers outside their country’s borders knew that any communication between them and any family still in Poland would have placed the latter in extreme danger. Besides that, those soldiers had no idea whether their families were still alive and still lived in their 1939 homes, or whether they had moved, or been moved, elsewhere during the occupations. By 1943, the Polish forces had been boosted by former inmates of Stalin’s forced-labour facilities throughout the USSR. They joined a new Polish army organised in Russia after Stalin gave them an ‘amnesty’1 to fight the Germans then invading Russia. That Polish army helped around 115,000 Polish military personnel and their families (including the 1944 Pahiatua refugees) to escape the USSR.

Warren is also not Polish, but his interest in the 733 Polish children who arrived here in November 1944 led him to Ann Jacques who, with her husband, fostered three of those children: Joseph, Jan, and Henryka Holender.

Through the archives at Manawatū Heritage, Warren discovered there was more to Ann Jacques than a woman kind enough to foster three Polish orphans. In late 1941, she heard about the loneliness of the Polish soldiers in north Africa and the Middle East, and created the Polish Army League for them. It became the conduit through which Ann and a team of dedicated Palmerston North women sent those Polish soldiers the same kind of “comforts” that their New Zealand counterparts regularly received—and mobilised nearly 8,000 New Zealanders to do the same. More than that, the PAL created a correspondence channel between the Polish soldiers and New Zealand penfriends.

The archives at Manawatū Heritage in Palmerston North hold the Polish Army League minute books and correspondence. It is thanks to that digitisation project, the digitisation of the archives held by papers past, and Warren Elliott’s encouragement, that I have been able to piece together this snapshot of Ann Jacques’ life.

—Barbara Scrivens

THE LITTLE SPARROW WITH A SPINE OF STEEL

by Barbara Scrivens

Ann Jacques gardened in high heels. They may not have been her best pair of shoes, but she had standards—even in her garden—and she maintained them.

Ann’s personality and drive did not need the few inches added to her five-foot, bird-like frame. Known in her community as a “little sparrow,” she had a strong sense of compassion and empathy, and championed those who could not speak for themselves. She did not appreciate, or tolerate, those who did not live up to her expectations of work and duty—no matter their status—and did not flinch from controversy.

In a letter to the editor of the manawatu standard on 12 May 1941, she scolded the city’s then-mayor, and other “prominent citizens” for not supporting public council meetings and events such as Palmerston North’s farewell to the former Governor-General of New Zealand, Viscount and Lady Galway.2

Her suggestion of two alternative candidates for mayor in the upcoming elections brought an abrasive rebuke3 that fell flat when another reader continued the letter trail by informing the newspaper’s readers of what Mrs Jacques had been doing the previous week:4

Good Neighbours

Following in the wake of Mr. J. T. Heatley (chairman of the works committee of the Emergency Precautions Scheme) and his gang of men who were hosing out houses that had been invaded by flood waters in Pahiatua Street yesterday, about 50 women, headed by Mrs. W. A. Jacques, rendered yeoman service with polishing rags and oil. Scrubbing and washing all came in the day’s work and it was some little satisfaction to see rooms looking homelike once more and to sense the gratitude for this timely help.5

The Jacques name had appeared regularly in Manawatū newspapers from the time the fielding star, the manawatu standard, and the manawatu times all announced on 6 December 1928, that the new Massey Agricultural College had appointed Mr WA Jacques to its field husbandry department.6

Then, Palmerston North’s readers found out that “Mr Jacques” had recently married a “Miss Jobson” and that their five-week sea voyage from England to New Zealand via San Francisco was a honeymoon.

William seemed to be an up-and-coming young man, who had won scholarships and exhibitions during his early agricultural studies. His father had been headmaster of the Church of England school in Burscough, and William Arthur Jacques was baptised at the St John the Baptist church in that parish in 1899. WWI interrupted his studies, but in 1926, he graduated from Bangor University in Wales with an honours’ degree in botany. The next year, he moved to Leeds University to take charge of grassland experiments—the kinds of experiments that interested the then-only school of agriculture in New Zealand’s North Island.

The Jacques disembarked from the makura in Wellington on 17 December 1928, having also stopped in French Polynesia, the Cook Islands and Sydney. Before travelling to Palmerston North, they probably visited Ann’s uncle, a Mr W Jobson, who had been mentioned in the newspaper articles as living in Wellington.

Massey’s new lecturer’s love of sports was soon apparent in the number of times he was listed in newspapers as part of local soccer and college hockey teams.

Ann’s family story7 is that her father, David Jobson, gave up three years’ medical studies in 1886, when an inheritance allowed him to move with his tutor to London and socialise with gentry, writers, and actors. The actress Lily Langtree introduced David to Ann’s mother, Clare McArdle, who then worked as an under-study. The two married in Leeds in 1891, and Ann was the second of their three children, born on 30 December 1893.

According to the 1901 British census, Annie K Jobson was born in the suburb of Kirkstall, the same place as her younger brother, Michael, in 1896. Her sister, Frances, was born in London in 1892, which indicates that David and Claire Jobson started their married life in that city.

The same family story says that the children were all educated in England while their parents lived, travelled, and worked “all over the world.”

Ann and William did not have children of their own, and fostered the Holender siblings after 1945, when it became clear that there was no free Poland for them to return to.

Both loved animals. Ann apparently decided that William was a man she could marry when she was paired with him in a tennis match in Leeds: Before the game, William picked up an earthworm from the tennis court, and placed it out of danger.

There is no doubt that the Jacques became known in Palmerston North’s social circles through William’s work at Massey, and the college’s social events.

Within a year of the Jacques arriving in Palmerston North, Ann’s name was appearing in the newspaper alongside her husband’s—and in her own right. In 1929, she was part of the organising committee for a dance held at the Empire Hall in aid of the Palmerston North’s Garrison Band. Ann’s high heels that night accompanied a gown of “pink and delphinium blue georgette.”8

Just a week later, the reviewer of a play at Palmerston North’s Opera House mentioned “Mrs Jacques” near the end of a long list of remembered patrons. It was the last time Ann neared the end of any list.

Ann continued her support of Palmerston North’s Garrison Band. Three months later, she was one of the stallholders assisting at the band’s annual fund-raiser, while her husband helped plant shelter hedges at the college.9

By May 1930, local newspapers showed that William and Ann both took part in regular golf tournaments—their home at 447 Albert Street was just 280 metres from the entrance of the Manawatū Golf Club. William played tennis too, and started to be invited to speak at some of Palmerston North’s social clubs. In June 1932, a regional gathering of Women’s Institutes heard his talk on garden planning, and in January the next year, he addressed the local Rotary club on the topic of life in Yorkshire.10

Ann and William would both have attended the Manawatū and West Coast Agricultural and Pastoral Association’s Spring Show held at Palmerston North in November 1931, where Ann’s cross-stitch entry won her second prize in the “Art and Industrial” needlework section.11

By September 1932, both were members of the Massey College SPCA, taking on cruelty to animals and better regulations for bobby calves, and planning a stall for the charity at that year’s Royal Show.12 In March 1933, at the second annual Parade of Pets hosted by the Palmerston North SPCA, members arranged exhibits, controlled the parade, and collected donations. Ann’s spaniel came second in the “Dog with the Largest Ears” category.13

The then-fledgeling Palmerston North SPCA became a cause close to Ann’s heart, and one that she worked for her entire life.

The branch had a precarious beginning. “Public Support Lacking” said the manawatu times headline when reporting the SPCA’s third annual report on 21 May 1929.14 The society’s balance sheet made its lack of funds clear, and an AGM heard how this was hampering its work. The next year, after its executive reported again about the “falling off of membership, subscriptions and donations,” the women of the soon-to-be city held a “dainty afternoon tea” with games of bridge, and succeeded in encouraging residents to start supporting the cause.15

_______________

Had it not been for the outbreak of WW2 in Europe, Ann Jacques may have remained a socialite devoted to her husband, her animals, and her garden, someone who could be relied on in times of crisis.

Crisis came with WW2. Ann, and many women she had become acquainted with in Palmerston North, joined the so-called patriotic drives to collect, make, and pack items to send to New Zealand servicemen abroad. Four times a year, each one apparently received a parcel from “home” that included cake, biscuits, and sweets in separate tins, tinned fruit, coffee, milk, processed meats, cigarettes, soap, razorblades, foot-powder, fruit salts, handkerchiefs, writing paper, playing cards, and small books. The Red Cross concentrated on sending weekly food parcels to the 8,469 New Zealand prisoners-of-war.16

In May 1940, women of Palmerston North immediately answered Governor-General Lord Galway’s appeal to those who did not enlist, to support his wife’s Patriotic Guild, which aimed to extend help to foreign refugees who had been entering Britain in their hundreds of thousands, people who “had neither homes nor countries and had lost everything” in the war in Europe. Ann Jacques became honorary secretary of Palmerston North’s newly formed Lady Galway Patriotic Guild.17

Two months later, she was among around 50 women who walked out of a meeting held to create another Palmerston North branch of the same guild. “Trouble was brewing” said the manawatu times, as it described the annoyance of people who objected to the city’s mayoress replacing Mrs Major Dick as chair.18

It turned out that the three members of the original May executive, who had met the secretary of the Lady Galway Patriotic Guild in Wellington, had been misinformed regarding how those guilds were to be run. Rather than lose the impetus and goodwill they had already created, the original May executive formed a United Guild—chaired by Mrs Major Dick—and continued to work for the refugees who had arrived in Britain.19 Ann Jacques became the United Guild’s honorary secretary, and Lady Galway seemed to have no problem with two guilds working separately for the same cause.

Once the Germans began their air raids over London on 7 September 1940, the number of British refugees within Britain increased dramatically, and the women of Palmerston North, along with other women in New Zealand, ramped up their collections to send overseas.

The number of people and organisations thanked at the end of each monthly report of the United Guild, made it clear that the women were efficient in channelling donations. Guild members met at the PDC (Premier Drapery Company) department store’s tearooms, and were “touched” by the quality of the goods sent in since the Blitz. The seamstresses mended and repaired, and made new garments from donated bolts of fabric.

They added hussifs (a fabric case for carrying sewing implements) to their inventory after one of the WWSA (Women’s War Service Auxiliary) organisers, a Mrs Atmore, visited their workshop and suggested that British women who had lost their sewing workboxes during the bombings would be “feeling a need” for some mending materials.20

Ann Jacques was among those presented to Lady Galway when the latter visited the United Guild’s workrooms in December 1940. One can imagine Ann’s gardening influence in the PDC lounge, “beautifully decorated” with lupins, bronze foliage, and lilies, and the spray of red roses that she presented to Lady Galway, who drank coffee from the “exquisite pink and white china” that she had lent for the occasion.21

_______________

The women of the United Guild were soon running an effective production line. They solved the lack of wool for knitting quilts by inviting spinning experts from a neighbouring institute to demonstrate the intricacies of extracting knittable yarn from raw wool. Ann learnt how to make gloves and, the next month, demonstrated the technique to fellow members.

Through visits and talks, the women of the United Guild fostered contact with groups that donated regularly.

The war may have been raging in Europe, but there was no reason not to grab a chance to create some enjoyment for a good cause. On 30 August 1941, the PDC held a fund-raising ball in recognition of the Navy’s work in evacuating New Zealand forces from Greece and Crete. Mrs Bale and Mrs Jacques were the first to be presented with honours.22

Ann Jacques was also patron for a newly formed Rosemary Club for the wives and relatives of soldiers.23

Ann wrote poetry. Her Requiescat in Gloria appeared in the manawatu standard on 14 October 1941:24

Dear Youth, that lived so short a time

Yet bore the burden of this age most vile,

And Christ-like bought our souls from misery

Paying the Devil’s score in blood and agony.

Brave Youth, whose clear true eyes

Saw safety as a dismal heritage,

Daring the highest venture, scorning cost

Tossed the bright coin of life, and lost.

Immortal Youth, when all our tears are shed

And we are in our graves, long dead,

In legend and in song your fame shall ring,

And you shall live while men of heroes sing.

—AK Jacques.

A day later, she would have read in the same paper about Polish and New Zealand troops “mingling” near the Nile, and how a New Zealand soldier with Polish parentage had “formed an acquaintance” with one of the Polish soldiers, who then wrote a letter to the New Zealander’s sister in Dunedin.25

The New Zealand soldier was Francis William Dysaski, a sapper with the 18th (NZ) Army Troops Company, New Zealand Engineers B Force, who was born in Southland circa 1904. The manawatu standard said the sister in question was a Miss AA Dysaski of Dunedin, which makes Francis William the fourth child of John and Mary (née Latchford) Dysaski, and Miss AA Dysaski his younger sister, Alice Ann. Their father was the fourth child of John and Julianna Dysaski, who had arrived on the palmerston in 1872 under the name Dysars, and with two daughters. (A third daughter, Anna Martha, was born at the Dunedin immigration barracks a month after the ship docked on 6 December 1872.26 ) On 30 December 1874, John junior became the second of four Dysaski children born in New Zealand. John and Mary Dysaski settled in Orepuki, where the children went to school, and where their father died in 1909 aged 34.

The unnamed Polish soldier wrote to Alice Ann Dysaski27 in Polish, which she could not understand. Neither could anyone she knew in Dunedin, so she forwarded the letter to the Polish Consul-General in Wellington, Count Kazimierz Wodzicki, who translated it for her: The soldier said that he valued her brother’s friendship, and that he had told him so much about the charm of and beauty of Polish girls that he doubted whether her brother would return directly to New Zealand once the war ended.

Ann Jacques kept up with the news, and there is no doubt that she monitored the progress of the war in northern Africa and the Middle East as well as in continental Europe and Britain. Stories about Poland’s plight, and the efforts of Polish troops, had been appearing in New Zealand newspapers since the beginning of the war. By October 1941, Hitler was four months into his attack on the territory of his former ally Stalin, who had by then turned to the Allies, including Poland, to help him save Moscow.

At the next meeting of the United Guild—within two weeks of reading the story about the Polish-New Zealand connection—Ann Jacques told members that she had arranged for the count’s wife to speak to them the following month, and that she would bring with her a Polish film taken from a German ship on the Pacific.28

_______________

The Wodzickis married the same year as the Jacques. Kazimierz Wodzicki was a biology professor at the Warsaw University College of Agriculture when the Germans invaded Poland in September 1939. In January 1941, the Polish government-in-exile appointed him its consul-general to New Zealand. He arrived in Auckland with his wife and two children on 25 April 1941.

When the news of the appointment first broke in New Zealand, newspapers wrote of “Professor” Wodzicki. Soon after the family’s arrival, when newspapers all over the country carried an interview with the new consul-general, they amended the title to “Count.”

According to that interview, he escaped Warsaw as the Germans invaded, and got to his family in the southern Polish mountains. He was then arrested by the Russian secret police, but managed to escape and return home again. By Christmas 1939, he had left Russian-occupied eastern Poland through Hungary, Italy, and France. In February 1940, his wife bribed a German officer with tea and coffee in exchange for a permit for herself, their two children, and their nanny to go to Italy for a ‘cure’ for their apparently ill son. The family reunited in France, where Kazimierz had met exiled Polish President General Władysław Sikorski. Both families then escaped to England, where General Sikorski relocated his Polish government-in-exile.29

Kazimierz Wodzicki visited Massey College in May and June 1941 in his capacity as a former professor.30 The college had invited him to visit the campus before he had been offered the consul-general job and he told Massey staff that he intended to combine his official duties with research on stock-breeding.31

Within such a small campus, it would have been inevitable for the new Polish visitor to have met faculty member William Jacques. The current war and its progression—top of mind for so many—had to have come up in conversation. It is not clear whether the countess accompanied her husband to Palmerston North, or whether a social gathering that included wives had been arranged for his visit, but the Jacques’ close marital bond meant the two would in any case have chatted about the visit, and the new consul-general—made perhaps more interesting when he told people that he was a count.

According to the manawatu standard, the Jacques hosted the countess at their Albert Street home the night before the she spoke at the United Guild’s meeting 28 November 1941. The countess met other members of the United Guild’s executive at the Jacobs’ home in Roy Street the evening before and the next day, she she “painted a vivid word picture of conditions in Poland in the early days of the German invasion.”32

With Count Wodzicki showing an interest in the work of the agricultural college, it seems reasonable to assume that he would have joined his wife at the Jacques’, and that during the visit, he would have shared with them the plight of around 10,000 Polish soldiers in the Middle East: They had been among the 63,000 who made their way to France, where they fought until its fall to Germany. About half those Poles were either killed or captured. The survivors went to Britain, where about 10,000 joined the Royal Air Force, a third were posted to defend the British coast, and the balance sent to the Middle East with the New Zealand Second Echelon.

One could assume that the count’s information came from a Mr Tadeusz Zażuliński, who, in his capacity as Polish Minister in Cairo, wrote to the Polish Consul-General in Wellington, and told him of the utter loneliness of the Polish soldiers who fought alongside New Zealanders in north Africa and the Middle East. With no way of finding out whether their families in German-occupied Poland were still alive, mail days accentuated their isolation when “stacks of mail came to [the New Zealanders] but never a letter arrived for a Pole.”33

An undated summary of the work of the Polish Army League by a Miss GC Tennent said that Mrs Jacques had been “permitted” to read Mr Zażuliński’s letter. It is not clear who gave her the letter, or where:

Later the same day, Mrs Jacques visited the Navy League, and conceived the idea of forming a similar organisation to “adopt” the Polish soldiers. On her return to Palmerston North, she invited Mrs E Bale to chair a meeting of sympathisers, and on December 14th, 1941… the committee was formed and the work was undertaken expeditiously and willingly… This small group of women formed the nucleus of an organisation which now spreads to all parts of New Zealand and numbers over 8,000 members.34

Back in December 1941, the women would not have had a notion of the number of New Zealanders they would eventually reach. If Ann had visited almost any Navy League depot in New Zealand, she would have seen the scope of the work that volunteers did in sending parcels and letters to sailors overseas. At the Polish Army League’s first meeting, she minuted its clear objective: To send letters and parcels to Polish soldiers fighting in the Middle East. Mrs LE Bale was elected chair, Ann Jacques, organising secretary, and also present were Mesdames A Stewart, PE Flood, and H Goot, and Miss M Greenwell.35

Within a week, the manawatu standard wrote about Mrs WA Jacques, in her role as patroness of Palmerston North’s Rosemary Club, making one of her first appeals for the Polish Army League.36

By 16 January 1942, the Polish Army League had had its first packing day, which during the next four years averaged one a month. With so many of the women also members of Palmerston North’s United Guild, it was inevitable that they chose to work in the guild’s room at the PDC department store. Its central location on The Square meant that no one who walked past could have missed their first window display, which showed a typical parcel and explained why it was there and where it was going.

The PDC (Premier Drapery Company) department store in 1950. These premises were built between 1929 and 1930, and became part of the PDC Plaza in 1986. The building was demolished in 1990.

That first packing day, Mesdames Cook, Brookfield, Garner, Fraser, Whitehead, Goot, and Jacques made up 30 parcels that they crated and forwarded, with an explanatory letter, to Mr Zażuliński, stationed at the headquarters of the Polish forces in the Middle East. Postage cost them 30 shillings.

The women were by then well-versed in packing parcels containing suitable items for soldiers and refugees. They had found out from Mr Zażuliński that the soldiers most welcomed razor blades, tinned foods, chocolate, handkerchiefs, cards, and socks. Into each individual parcel of “home comforts,” the women of the PAL also added a letter, thanks to Mrs Goot, who was Polish and who helped the women write suitable messages in Polish, including the words “Niech Żyje Polska.“ (Long Live Poland.)

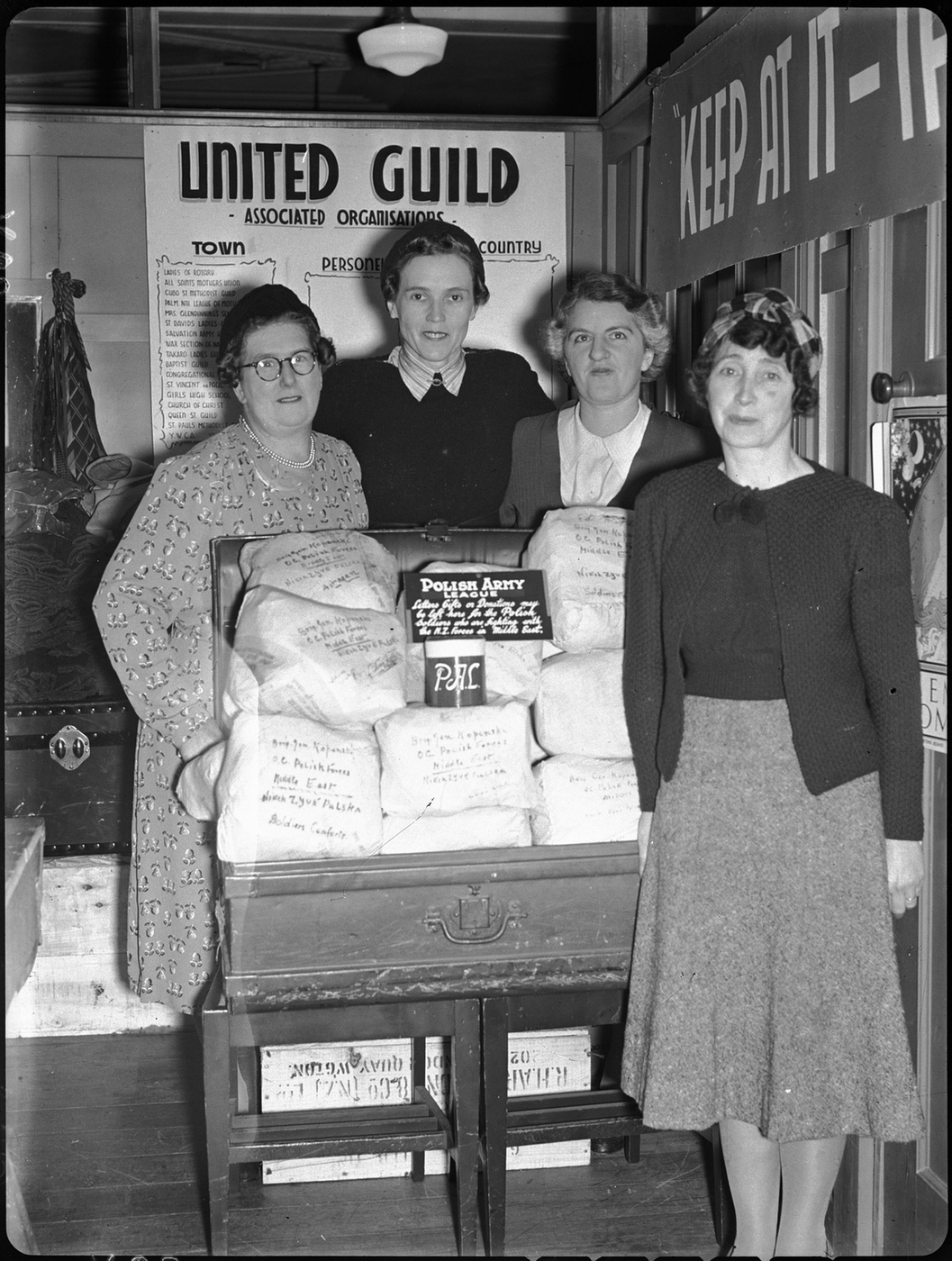

With some of the first parcels addressed to the Polish forces in the Middle East, packed by the women of the Polish Army League, from left: Mesdames Stewart, Bale (chair), Fraser (treasurer) and Jacques (organising secretary). The notice among the parcels says: “Polish Army League – Letters Gifts or Donations may be left here for the Polish Soldiers who are fighting with the N.Z. Forces in the Middle East.” During the next several years, the women of the PAL epitomised the slogan on the right: “KEEP AT IT.”37

The Polish Army League’s attempts at informing the New Zealand public about Poland’s plight did not always flow smoothly. “What’s wrong with the typesetter?” Ann scrawled at the top of the manawatu standard article about the first PAL shipment, which she cut out and pasted into the first minute book. Either the reporter, the typesetter, or the proof-reader had not believed the numbers, and had reduced them from the 63,000 Polish soldiers who had escaped to France, to 6,300. They compounded their mistake by saying that only 3,600 Poles arrived in Britain, and only 1,000 joined the RAF.38

The newspaper posted a correction and days later, also printed a letter to the editor from Consul-General Wodzicki reiterating the numbers of Poles then involved in the European conflict: By 1942, the 30,000 in Britain in 1940 had been increased by Polish soldiers, sailors, and airmen who had escaped occupied Poland through Portugal and Spain. Nearly 10,000 of the Poles who had fought with the Vichy French in Syria, had made their way through Palestine and Egypt to the Western Desert, where they had been mentioned in “almost every battle in despatches.” A third Polish division had formed in Canada, and the Consul-General expected the Polish army then still being formed in the USSR under General Anders, to reach 100,000.39

_______________

New Zealanders who read the newspapers did not seem to question how or why there were that many Polish men in the USSR. In October 1941, the evening post was one of several newspapers that ran with the headline READY FOR WAR; POLES IN RUSSIA; FULLY-ARMED DIVISION and two paragraphs that said Russia was “giving every assistance in bringing together and organising Polish soldiers scattered throughout Russia.”40

On 20 June 1941, those Polish soldiers and their families were indeed “scattered” in Soviet-run forced-labour facilities throughout northern Russia and Siberia, and kolkhozes in Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. In February, April, and June 1940, and in June 1941, they had been kidnapped from their homes in then-eastern Poland by the NKVD, aided by Ukrainian neighbours turned Soviet sympathisers. The Stalin regime had classified the Poles as “anti-Soviet elements” and removed at least 1.5 million Polish men, women, and children to the USSR, mostly in cattle-trucks.

But on 21 June 1941, during the so-called “fourth wave of deportations” of Poles into the USSR, Hitler’s troops crossed the German-Russian border that Hitler and his then-ally Stalin concocted in the middle of Poland in the weeks before they invaded Poland on 1 and 17 September 1939.

As the German army moved east across Russian-occupied Poland, and then into Russia proper, the ‘deportations’41 stopped, and many Poles already on the way reached only as far as Kazakhstan or Uzbekistan. Stalin, and his Soviet Union turned to the allies: Germany had become their joint enemy.

Hitler’s move meant that it was in Stalin’s interests to mobilise the Polish adults he had illegally imprisoned into an army that would fight to protect Moscow. Polish president-in-exile General Władysław Sikorski used the opportunity to sign a Polish-Soviet agreement on 30 July 1941 to release the Poles from the hundreds of forced labour facilities that were indeed “scattered” throughout the vast Soviet Union. That New Zealand newspapers were talking about an army of just 100,000, and the fact that that only around 115,000 soldiers and civilians escaped with the Polish army in 1942, shows how many perished, or remained behind after the USSR borders closed shortly afterwards.42

At the end of 1941, the Poles who were already fighting alongside the Allies in WW2 were those who had escaped Poland before its borders closed. After the ‘amnesty’ agreement of 30 July 1941, the Poles scattered throughout the USSR had to make their own way to the Polish army being formed in Tashkent, Uzbekistan—journeys of thousands of miles and much by foot. In his November 1941 speech, the consul-general spoke of the “one thousand strange, barefooted ragamuffins… all exiled from prisons or prisoner-of-war camps” who were then enlisting daily into that new Polish army. He hinted that the “Don’t Talk” campaign prevented him from revealing too much of what Poles still in German-occupied Poland were doing.43

_______________

Ann Jacques would have been any committee’s dream organising secretary. She knew how to spread the word. She made sure that on packing week, local newspapers carried advertisements announcing the packing and asking for donations.

More from Miss Tennent, as she looked back:

As a means of imbuing others with her enthusiasm, Mrs Jacques knitted innumerable pairs of peasant gloves from home-spun wool and gave them to any of her friends who agreed to send a parcel to a Polish soldier. No other appeal for funds of any sort has ever been made, and yet, impossible as it may appear, the committee sent fifty parcels per month to hospitals in the forward areas right up to the cessation of hostilities. It would be impossible to even estimate the numbers of parcels sent from League members to the soldiers of their “adoption.”

The Polish Army League was a well-run machine for good reason: committee members and supporters had known one another for years, through Massey or the many clubs and associations that proliferated Palmerston North. They used their connections to encourage clubs all over New Zealand to donate—and they did. By the PAL’s second packing day in February 1942, “numerous” organisations all over “the Dominion” had requested more information about the league’s operation and organisation.

For a secretary, Ann had atrocious handwriting—she had acute neuritis—but she kept meticulous notes with numbers confirmed elsewhere.

According to her minutes, clubs and institutions in Palmerston North that collected, made, and donated goods included: the [United] Guild Spinning Circle, the Happiness Club, Johnson’s Circle, the Kowhai Garden Circle, the Manawatu Country Club, students and staff of Massey College, the Methodist Guild of Cuba Street, the National Club, the students and staff of Palmerston North Girls’ High School, the management and staff of PDC, the Rosemary Club, St David’s Guild, St Vincent de Paul Society , the WDFU (Women's Division of the Farmers' Union), and the YWCA (Young Women’s Christian Association).

Local people who donated but were not on the PAL committee included Mrs Aubrey, Mr Hickin, Mrs Ciochetto, Miss Cooks, Miss Sillees, Mrs Rendall, Mr Billens, Mrs Hill, anad Miss Paihu Moore. A “young helper” Rosemary Johnson involved her friends.

The local Knitting Mills donated wool and Foole Bros donated socks. The New Zealand Farming Corp donated 17 bags of fleece and a Mr Johnson of Whangarei collected two bales of black wool and three bales of fleece from north of Auckland, which encouraged Ann to learn to spin and, with Mrs Whitehead and Mrs Johnson, to establish the Glove Co. They, and Mesdames Stewart, McKechnie, Wilde, and Fraser met every Saturday for two and a half years to make items for the parcels, but the company lapsed after Ann’s neuritis finally curtailed her fine motor abilities.

Outside Palmerston North, Adams Bruce Ltd donated cakes, and when they were later unable to do so, the women baked biscuits. Other donations came from the Eskdale Children’s Home, Happiness Clubs in Wellington, the Wanganui Catholic Ladies’ Knitting Circle, the Takapau Red Cross, and people like Mrs Hamar of Eastbourne, and a Miss Hussey of Wellington. A Mrs Fowler of Motueka sent a large parcel of woollies, underclothes, pullovers, socks, and handkerchiefs.

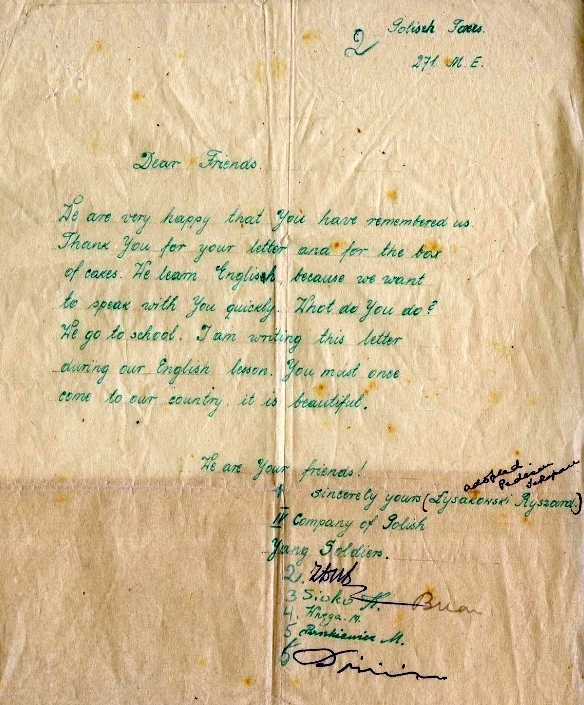

By November 1942, the Polish Army League in Palmerston North packaged and sent more than 600 parcels, and other members brought that number up to 1,000. Their gesture surprised the Polish soldiers in the Middle East, who replied to the “many” letters saying how much they were touched by the kindness of strangers. Soldiers who were students at Warsaw University before WW2 wrote in English, cadets wrote in their English classes, and groups wrote jointly.

This letter came from a group of “Young Soldiers“ in the Fourth Company. Their description of themselves, and the fact that their address is the Middle East, suggests that they were military cadets, or junaki. The Polish army that escaped the USSR with General Anders in 1942 realised that there were many teenaged boys and girls who, until they were old enough to enlist, would benefit from structured schooling with professional role-models.

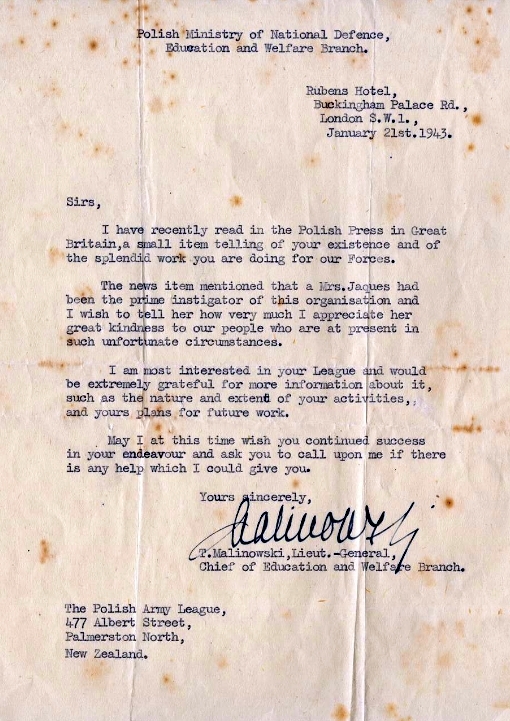

News of what the Polish Army League was doing in New Zealand reached Polish newspapers in England, and Lieutenant-General T Malinowski, Chief of Education and Welfare of the Polish Ministry of National Defence in 1943, who was part of Polish Prime Minister General Sikorski’s government-in-exile, then based in London.

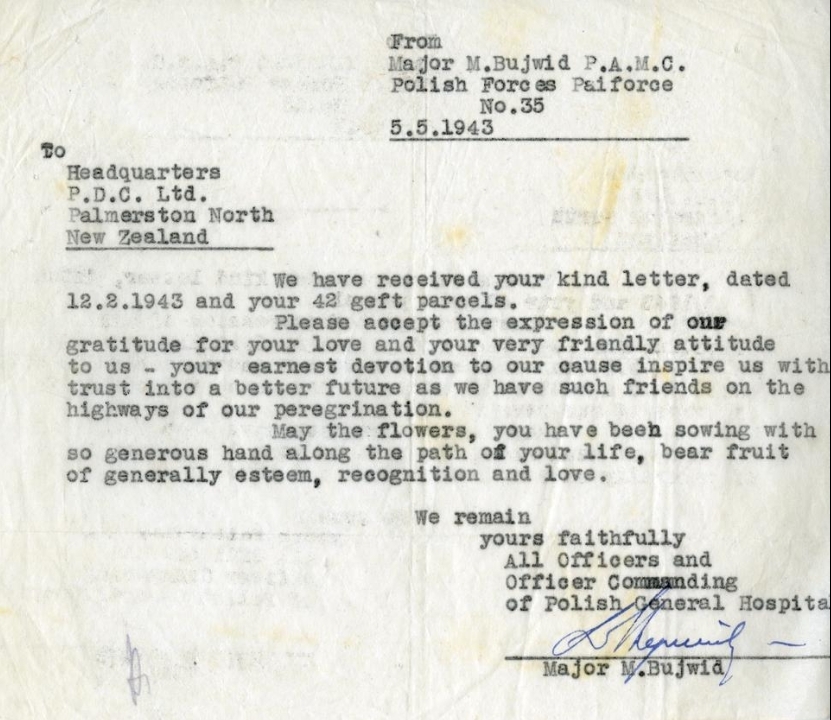

Polish forces in the Middle East and north Africa forwarded many of the Polish Army League parcels to hospitals with Polish soldiers. Major Bujwid’s letter epitomises the Poles’ deferential and charming turn of phrase. The Paiforce (Persia and Iraq Force) in the name suggests these soldiers may have been hospitalised after their ordeals in the USSR.

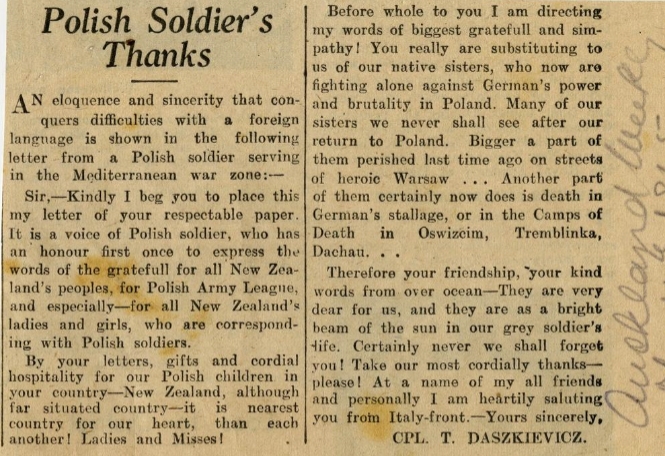

The Auckland Weekly published this letter from Cpl T Daszkiewicz on 15 February 1945.44

_______________

After the Warsaw Rising in August and September 1944, and the arrival of 733 Polish children and their 105 Polish caregivers in Wellington in November 1944, the PAL included the two new causes in donations. The PAL helped to make the Polish children’s camp in nearby Pahiatua as welcoming as possible, and later continued to ease the lives of the children.

When the 838 Polish refugees travelled by train from Wellington to their accommodation at the Pahiatua Children’s Camp in Pahiatua, they thought that their stop in Palmerston North was for “refuelling.” Between Wellington and Palmerston North are 115 kilometres. Between Palmerston North and Pahiatua are 15 kilometres. Ann Jacques and the PAL made sure that the Poles on those trains got the full bolt of New Zealand hospitality. The rail tracks then ran through the city centre, and the trains stopped there.

Ann was at the inaugural meeting of the Polish Children’s Hospitality Committee, five days before the uss general randall arrived with the Polish refugees.45 The meeting heard that the camp at Pahiatua was ready for the children and their caregivers, and that thousands of pieces of clothing and other items had been donated through various organisations, but camp commandant Major Foxley made it clear that the children were to be taken from the ship to the camp as quickly as possible. Although there would be people to welcome the group in Wellington, he intimated that a reception at the wharf was not possible—wartime port authorities “did not like giving passes.”46

Ann discussed her plans for the Poles’ Palmerston North train stop with the rest of the PAL team, which contacted groups such as the local Red Cross, Scouts, and Girl Guides to arrange a joint “programme” scheduled to last 20 minutes and that included welcoming the two trains with “light refreshments such as fruit, sweets etc—no speeches.”47

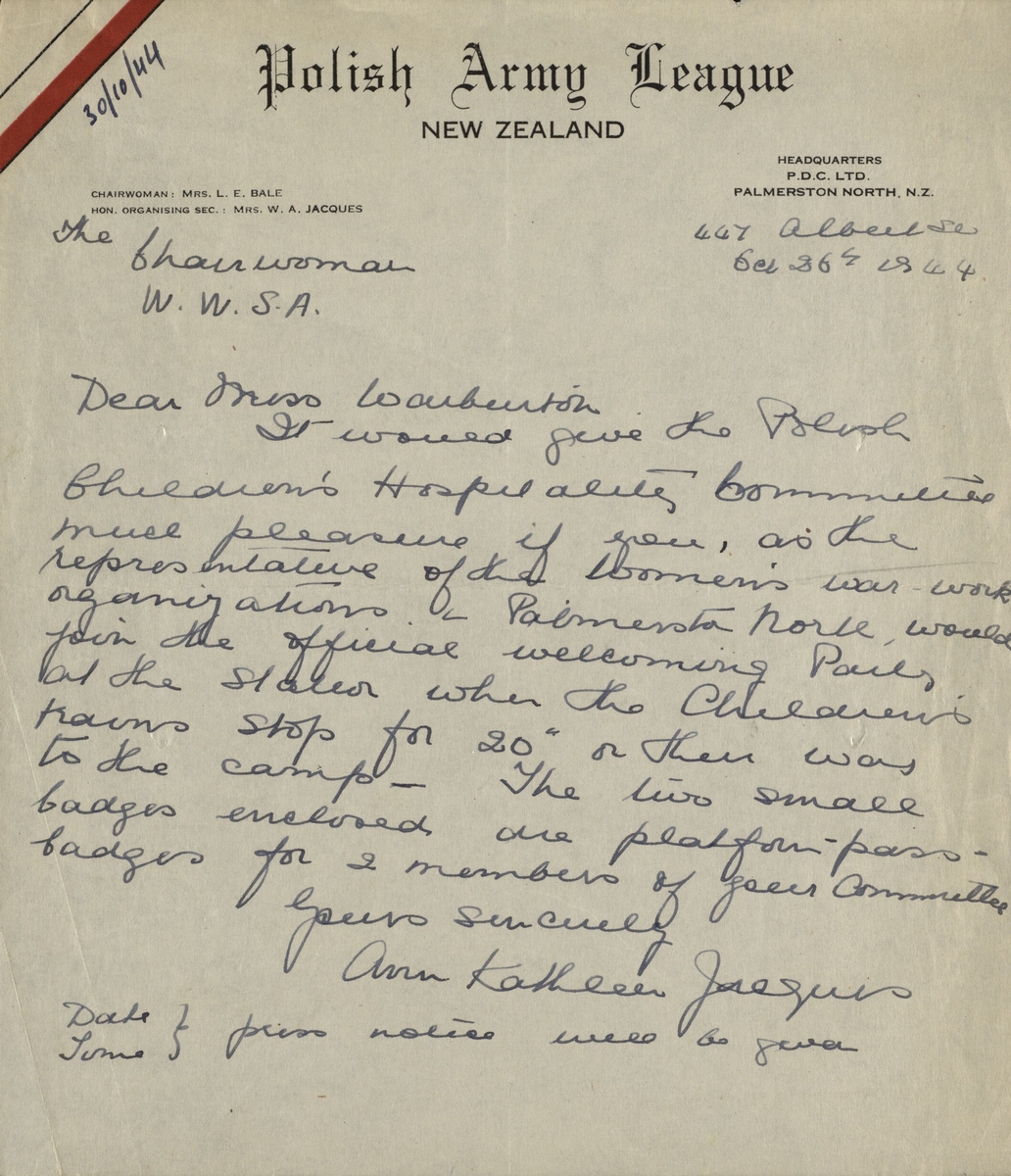

Mrs Jacques’ letter to Mrs CE Warburton, chair of the Palmerston North district committee of the WWSA, and well-known in the city for her war efforts. It shows Ann’s ability to encourage local residents with connections, and her eye for detail, in this case by arranging the platform passes.48

Thanks to the work of the PAL during the preceding years, Palmerston North residents in 1944 were well-aware of the plights of the Poles caught in war. Now they had the chance to meet some of them in person. The 20-minute stop turned into one lasting two hours. That stop became a special memory for the Poles, who were surprised and touched by the warmth they received.

Residents who lived along the railway lines had already come out to wave to the train. The Poles had arrived in a place where they were so obviously welcomed and, after their years of hardship and exile in the USSR and the almost two-year stay in orphanages in Isfahan, in then-Persia (now Iran), they appreciated it.

At the railway square in Palmerston North, residents lined the streets, and local children, who got the day off school, jumped into the carriages and distributed flowers, chocolates, and gifts, and exchanged autographs with their Polish counterparts.

Allan Hughes was one of the schoolboys:

“We knew these people couldn’t speak English and we couldn’t speak Polish so how do you communicate? It was a bit awkward in the beginning but that broke down after a very short space of time. These kids couldn’t believe the sheer volume of stuff being given to them—chocolates and lollies and books and toys and writing gear and comics—people just brought what they could and as things began to run out, they went back to their homes to get more.”49

A manawatu evening standard story the next day said:

Long before the first train was due to arrive the crowd was so dense on the station that there was little more than standing room and welcoming crowds also flanked the railway line through the Square. On the platform the Girl Guides, holding red and white streamers, formed the Polish flag, above which was the word “Witajcie” (Welcome), while colour parties of Guides and Boy Scouts stood at the back holding the Guide International Flag and the Polish and New Zealand flags.

A tumultuous shouting from the New Zealand children greeted the first train as it drew into the station, and the Guides surged forward to present the visitors with apples, sweets and floral posies.50

Photographer John Pascoe, who travelled with the Polish contingent, took this image as the trains slowed through Palmerston North on 1 November 1944.51

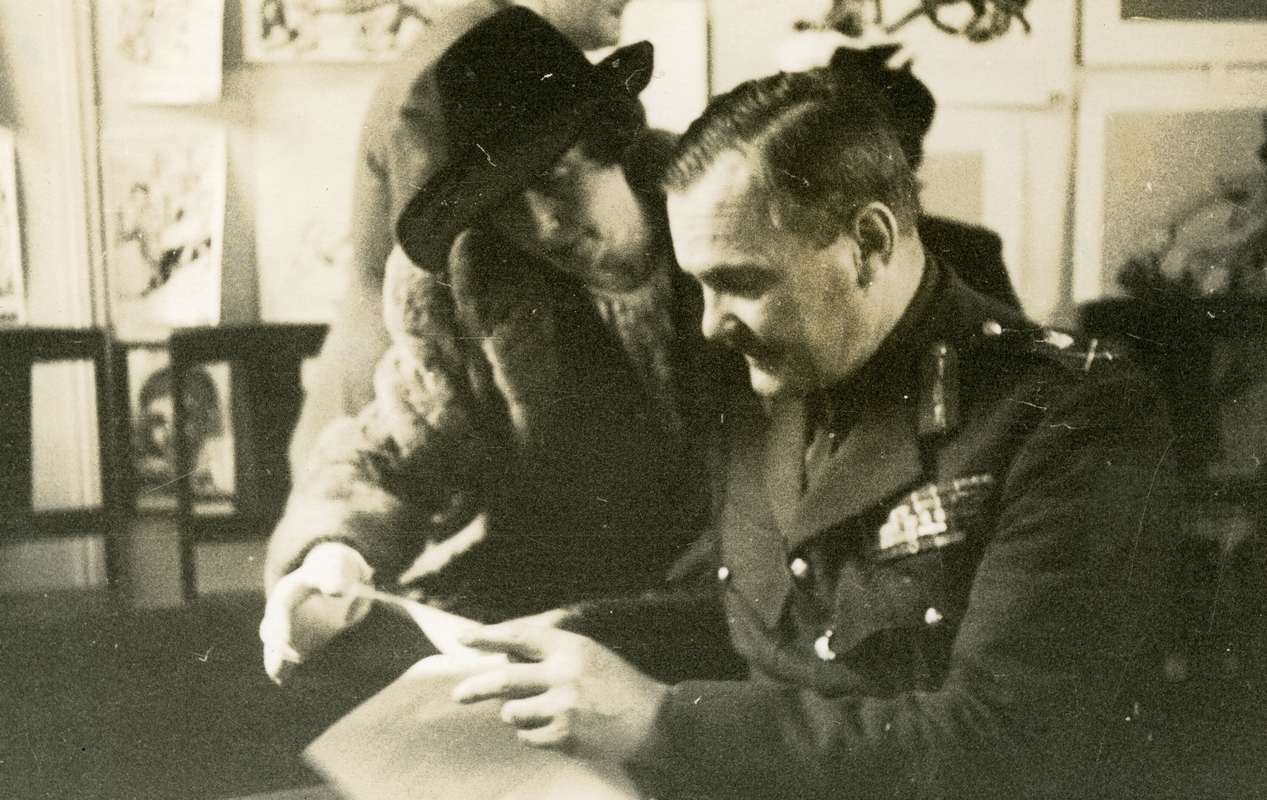

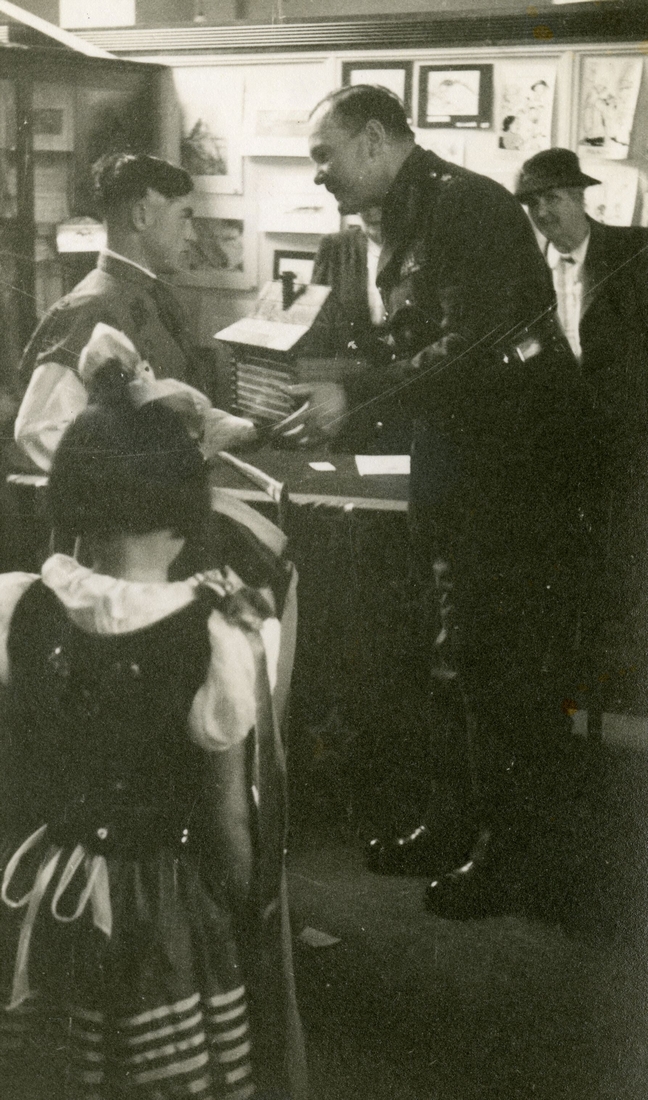

From then on, the PAL added the Polish children to their list of Polish causes. Three months later, members arranged a fundraising afternoon tea at the PDC to complement a week-long display of cartoons they received from the Third Carpathian Infantry Division, then in Italy. It was that division’s solders who received the PAL’s first batch of parcels. The PAL arranged a choir of 40 and dancers from the Pahiatua camp. Almost twice the number of 200 expected guests packed the room to hear and see the young Poles, and guest speaker Brigadier JRF Sherston, former Chief Liaison Officer for the Allied Armies in the Middle East. Among his other jobs in Teheran, Brigadier Sherston received the Polish refugees from Russia.

Little Poland Comes To Palmerston North said the manawatu times headline on 17 February 1945. The lengthy story ended:

Those who were at the station when the Polish visitors passed through on their way to Pahiatua and saw them again on Thursday must have been amazed at the transformation. To-day the children are normal, smiling and rosy-cheeked and demonstrated in their singing and dancing that something of the joy of life has come to them once more.

The unaccompanied part-singing of the choir was a rare treat and would have done credit to a much older group. Folk songs were sung with deep expression and delightful harmony winning a spontaneous tribute from the audience. Old Polish folk-dances also captivated those present. First came a group of eight tiny maids in the picturesque national costume with wreaths of flowers in their hair and flying ribbons performing with natural grace and rhythm, then older girls in a more vigorous measure and finally a dance of the mountaineers by two different pairs.

All the costumes had been made recently by the children from odd bits and pieces, the high boots worn by one group being made from a scarlet blanket. As a gracious gesture the choir terminated proceedings with the British National Anthem sung in English, a language of which they knew little or nothing three months ago.52

The PAL’s work on the Pahiatua Hospitality Committee continued throughout 1945. At one stage, translating the letters from Polish soldiers became tougher, as the countess apparently became ill and the few Polish people able to translate became “terribly busy.” Ann negotiated the visit of 25 Polish girl guides to the city, and places for two Pahiatua girls on a six-month course at the New Zealand School of Hair Dressing. Mrs Flood hosted them, and the Jacques hosted the Polish mother of an ill child for three weeks, so that she could be near the hospital.

PAL minute books show that its members made regular trips between Palmerston North and Pahiatua, as they helped with transporting children who had gone on trips, and delivering goods to the camp. On 27 May 1945, Mrs Stewart joined Ann and William on such a visit “taking children back to the camp so that goods were delivered to the Hands of the Headmistress of Kindergarten.”53

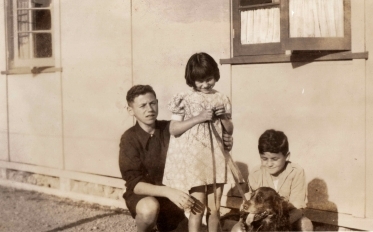

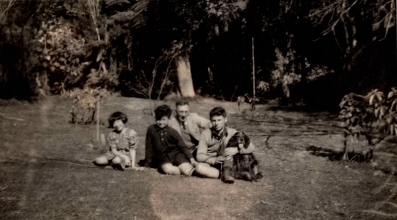

The spaniel in the foreground of this photograph, and the distinctive walls of the building next to the children, indicates that Ann Jacques took this photograph of Joseph, left, Henryka, and Jan Holender on one of her early visits to the Pahiatua children’s camp. Joseph was born in 1930, Jan in 1936, and Henryka in 1938.

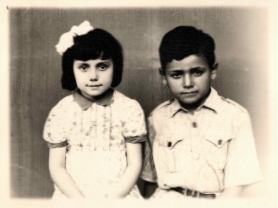

Henryka and Jan Holender.

For Ann Jacques to have this photograph in one of her albums, the girl on the left is Henryka Holender, and the photograph was taken at the Pahiatua children’s camp.

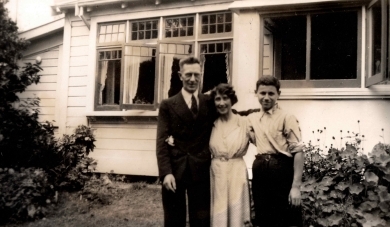

This photograph has appeared in several stories about Ann Jacques and her work with the Polish Army League. It is described as a garden party to raise funds for the SPCA, which included in its programme dancing by the girls in front, who were from the Polish children’s camp at Pahiatua. Ann is seated in the middle of the three women. The woman on the left is a Miss Mervid, and on the right is Mrs Jadwiga Tietze, on the camp’s staff. William Jacques is immediately behind his wife, and the hatted man at the back is described only as the “headmaster” of the children’s camp.54

The photograph above answers a few questions and raises others. It describes William as chairman of the Polish children’s camp “Board of Guardians.” But—the archival details say that it was taken at Nettleworth, in Ihaka Street, Palmerston North, the home of the president of the SPCA, Mr W Jacques. But the Jacques lived in Albert Street, 500 metres away, and William was the chairman, not the president of the SPCA, who was then a Mr Learmonth. And Nettleworth was the home of the Fitzherbert family, whose widow was a vice-president of the Palmerston North SPCA in October 1945. The photograph is also dated 1944, which may have been a bit early, as the children only arrived in New Zealand on 1 November that year. The “headmaster” is probably Mr Jan Sledzinski, the camp’s official overseer for the Polish government-in-exile’s ministries of social welfare and education.

Judging by the suit and tie that William is wearing, the distinct position of the pen in his pocket, and the person in costume in the background, this photograph was probably taken on the same day as the one above. The archival caption names the children as Jan and Henryka Holender “from the camp,” and again mentions William’s position on the camp’s “Board of Guardians” and that he was a lecturer at Massey Agricultural College.55

William Jacques and the Jacques’ spaniel with the Holender siblings in the Jacques’ garden at 447 Albert Street, Palmerston North.

WIlliam and Ann Jacques with Joseph Holender.

_______________

In May 1945, the manawatu standard reported that Countess Wodzicka had “consented to become president of the New Zealand Polish Army League.” PAL minutes did not say why this position was created, merely that she had asked for a list of foundation members, apparently for Captain Adam Kubaczka of the Third Carpathian Division. The short newspaper piece quoted the countess only, and reported that, “It was due to the interest roused by the countess that the league was originally formed, and she has since acted as liaison between it and the Polish Army in the Middle East.”56 It is not clear why the countess would have thought that the women of the PAL needed a liaison: from the time that they sent off their first parcels to Mr Zażuliński in Cairo in early 1942, they had been quite capable of speaking for themselves.

On 20 December 1945, an article in the manawatu standard, described the Polish Army League’s “Fine Record of Work.”57

… The league has never made any appeal for funds, each member being responsible for her own parcels, but the committee from the first has maintained the practice of packing gift parcels to the Polish hospitals and to men of the [Third] Carpathian Division. In order to do this they gave up every Saturday afternoon to sewing and knitting, making hussifs and toilet bags and spinning the yarn winch they made into socks, scarves, and pullovers. The results of this effort were augmented by gift parcels from the Women’s Division of the Farmers’ Union, Palmerston North National Club, the Palmerston North Happiness Club, the Girls’ High School, Rosemary Club and many other sympathetic organisations; in fact, it was largely due to the generous support of these Palmerston North people that the work of the league became so quickly established and spread to every part of the Dominion. It has been stated that as a result of the league’s activities the Polish Field Post Office has been changed overnight from being a sleepy sorting house of official documents to a lively and active office for friendly letters and parcels from the other side of the world.

That these letters are genuinely appreciated is evident from the replies received, and for the majority of the Poles these are the only letters during six long years of war and exile. It is estimated that pen friendships have been arranged for upward of 6,000 soldiers. After four years of steady work, the committee can view with satisfaction the results of their efforts, and their reward lies in the knowledge that they have done something really worthwhile. They have worked without funds, without any official backing, and with little or no recognition either here or overseas, but their accomplishment has its own testimonial and all the reward that any one of them could desire. Every Pole in the Central Mediterranean Force knows of the Polish Army League and thinks of it as one of the few bright spots in his otherwise sad and arduous life.…

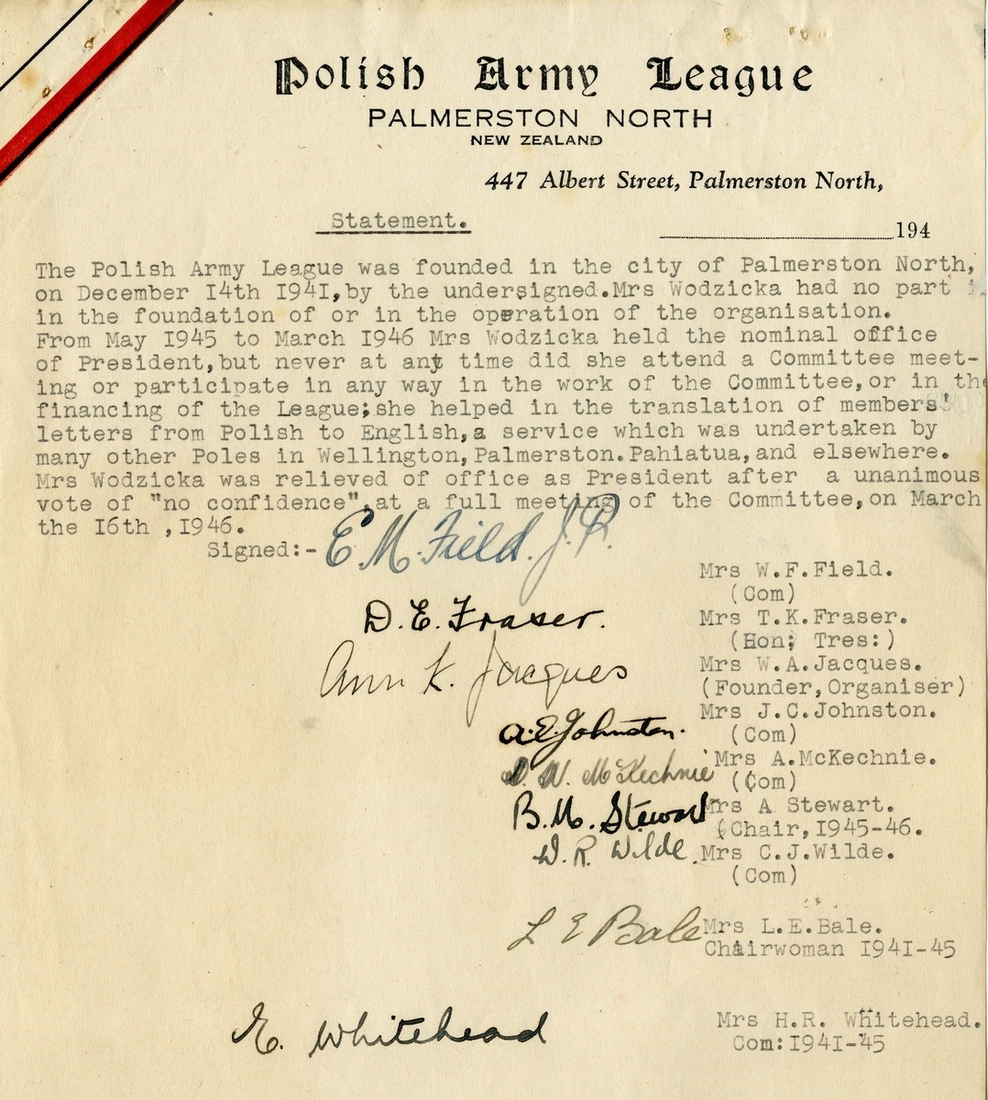

The relationship between the countess and the PAL deteriorated soon after. A special PAL meeting on 16 March 1946 unanimously carried a vote of no confidence, and “madam [was] relieved of office.”58

The PAL women were proud of the work they had done. Not only had they willingly given up hours of their time to help others, but they had also personally and quietly borne any costs. They did not appreciate it when they found out that that the countess had been paid for what they had assumed—and been led to believe— that she had been doing voluntarily. They were particularly aggrieved by her receiving £300 a year for “PAL work,” from an entity Mrs Jacques minuted as “NPF Bd” (the National Patriotic Fund Board), that she had used PAL stationery to appeal to the entity, and that she had said that she had translated the letters of 1,000 soldiers.59

By then, there were “upward of 6,000” soldiers writing to the Polish Army League, the majority writing in English, or getting friends who knew English to write for them. The Polish camp at Pahiatua supplemented the translation work done voluntarily by more than a dozen others, including Mr and Mrs Goot, who helped pen the letters in the first parcels in 1942.

In May 1946, the PAL sent out a statement regarding its translators, and put a terse 29-word advertisement into the dominion in Wellington requesting that its members arrange translations through 447 Albert Street rather than 26 Kelburn Parade, which was then the Wodzicki’s private residence.60

The Polish Army League sent a second statement, below, regarding “Mrs Wodzicka” and her relationship to the Polish Army League to: Captain Kubaczka, with whom they had previously corresponded; to the chairman of the Interim Treasury Committee in London; and the chairman of the Polish Red Cross in London. The statement documents Ann Jacques as the founder of the PAL, and records the other eight women who played such a huge part in its work: Mesdames LE Bale, EM Field, WF Fraser, JC Johnston, A McKechnie, A Stewart, CJ Wilde, and HR Whitehead.61

The committee was already concerned by the fact that during 1945, they had received not a single letter of acknowledgement of parcels from Polish authorities overseas. Mr Sledzinski apparently wrote to General Duch, in charge of Soldiers Social Welfare, Third Carpathian Division, “on behalf of the count” and asked for an investigation: the missing letters had apparently been directed to an address in Wellington.

The “NPFd Bd” cancelled its grant to Mrs Wodzicka and in July 1946, and the PAL tightened other possible loopholes that might lead to other misunderstandings. Ann would sign herself as “organiser” rather than “secretary,” the executive would be reduced to a core of three—Mesdames Jacques, Wilde, and Field—to “carry on the work of the league as long as there was work to be done,” and the balance of the committee would go into “recess… not disbanded.”62

_______________

In 1946, shortly before they started to leave Italy for Britain, the soldiers of the Third Carpathian Infantry Division sent 17 cases of their own artwork as gifts for the Polish Army League. The works had been displayed at Cupra Marittima, Italy, before despatch, and included watercolours, oils, cartoons, woodwork, and metalwork.

Three of the soldiers who gave their work to the Polish Army League, from left cartoonist Mietek Kuczyński, and painters Feliks Krzewiński and Jan Bednarski. This is the exhibition that was displayed at Cupra Marittima.

Feliks Krzewiński’s depiction of the Black Madonna, a venerated icon in Poland, is the one in the centre background, above. The words below her are from Polish military leader Józef Piłsudski: “Nasza największa siła jest nasza wiara. Strzeżcie jej, wzmacniajcie ją.” (Our greatest strength is our faith. Guard it, strengthen it.)

The PAL organising machine made sure that the gifts, and the Polish story, had the best exposure. An exhibition in Palmerston North later moved around the country. CM Ross Co Ltd hosted the first one, opened by the new Governor-General Lieutenant-General Sir Bernard Freyberg on his first visit to Palmerston North on 19 September 1946, three months after taking office. (He and Lady Freyberg arrived in Wellington on 17 June 1946.)

In the lead-up to the exhibition, Mrs Jacques wrote of the CM Ross management’s being “most kind & helpful,” how the mayor, Mr Mansford, “could not have been kinder or more helpful” and of Mrs Kalińska of the Polish camp “generously coming over to help especially with the exhibits.”63

Mrs Wanda Kalińska, the Pahiatua camp’s craft teacher, with some of the exhibits created by her students. Boys made the Polish national designs on wood, and the girls embroidered traditional designs.

The new Governor-General’s appearance at the opening of the exhibition had a special significance, as he had commanded New Zealand troops in Italy, who remembered “with great affection their comrades in the Polish Corps.” He said that he was “pleased to have the three Polish commanders, General Anders, General Zulich and General Duch among his closest friends” and that he had opened the original exhibition in Italy the year before. Exhibits were given as an expression of gratitude to the soldiers of the Dominion, with whom the Poles served in north Africa and Italy, in thankfulness for the hospitality extended to the Polish children at Pahiatua, and for the interest taken in the Polish forces and children by the Polish Army League.64

New Zealand Governor-General, Lieutenant-General Sir Bernard Freyberg with Ann Jacques at the opening of the exhibition of gifts from Polish soldiers on 19 September 1946.

Lieutenant-General Sir Bernard Freyberg, with Mrs E J Wilde, treasurer and founding member of the Polish Army League, at the opening of an exhibition of art works gifted to New Zealand.

General Freyberg with the chair of the Polish Army League, Mrs W Field, at the opening of the exhibition of Polish soldier’s gifts. Mrs Field was one of the founding members of the PAL.

Kazimierz Walczak was 17 when he asked Sir Bernard to forward to Prime Minister Fraser, this model of a mountaineer’s hut that his father had made in gratitude for the hospitality extended to his son and the other Poles. Kazimierz, one of the Pahiatua children, arrived in New Zealand alone. Post-war communications helped him find three other siblings: Aleksander, Janina, and Antonia, and his father, Józef Walczak, who arrived on the hellenic prince in October 1950 with 217 other single men through Germany’s immediate post-war British zone.65

The door’s hinges, studs, and carving show the time and effort that Kazimierz Walczak’s father, Józef, put into the intricate model mountain hut that he made for New Zealand Prime Minister Peter Fraser. According to the hellenic prince passenger list, Józef Walczak’s pre-war occupation was blacksmith.

At the exhibition opening: William Jacques in the joint capacity of supporting his wife and the PAL, and as chairman of the Pahiatua children’s camp board of guardians, and New Zealand’s Governor-General Bernard Freyberg.

By 1946, it was clear that the New Zealand government’s original plan to care for the Polish refugees for the balance of the war had to be amended: Poland was not the free country that its ground, sea, and air forces had fought for.

On the same day as the exhibition, the dominion in Wellington reported Prime Minister Fraser’s decision about what to do with the Polish refugees of 1944: those who wanted to settle permanently in New Zealand “would be welcomed” while those who wanted to return to Poland were “entitled to do so.” Children who had not yet reached the “age of discretion” would be able to decide for themselves when the time came.66

The PAL continued its parcel and letter campaign until September 1945, when the last went to Polish troops in Italy.

The end of the war in Europe ended the pressing need for parcels and letters to the Polish troops, but there was no sudden abandonment on the part of the PAL.

Although most Polish military personnel decided against returning to then-communist-controlled Poland, organisations such as the Red Cross continued to help them reconnect with the survivors of their own families, either in Poland or in Polish refugee camps such as in Pahiatua, or in eastern and southern Africa, Mexico, and Argentina, or IRO (International Refugee Organisation) facilities in western Europe.

From July 1946, the UK had started accepting Polish soldiers, but its politicians continued to urge them to return to their homeland. In 1947, the British government finally accepted that it had a responsibility to the Poles who had fought with the Allies, and introduced a Polish Resettlement Act, which demobilised 250,000 of the then stateless Poles into a Polish Resettlement Corps, and created a two-year window for them to train and integrate into life outside their homeland.67 They and their families stayed in scores of so-called Polish Resettlement camps throughout Britain.68

_______________

Members of the PAL throughout New Zealand corresponded with up to 10,000 Polish soldiers; many of whom responded to the “comfort” parcels they received with their own hand-made gifts.69

On the Polish Army League’s fifth anniversary, General Duch sent each member of the committee a bracelet made of linked medallions: “In relief on the centre medallion is Monte Cassino and on each other link is a tiny plaque with an emblem of a Polish Army Division.”70

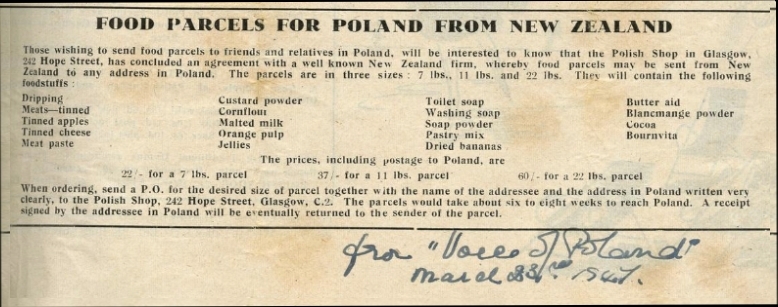

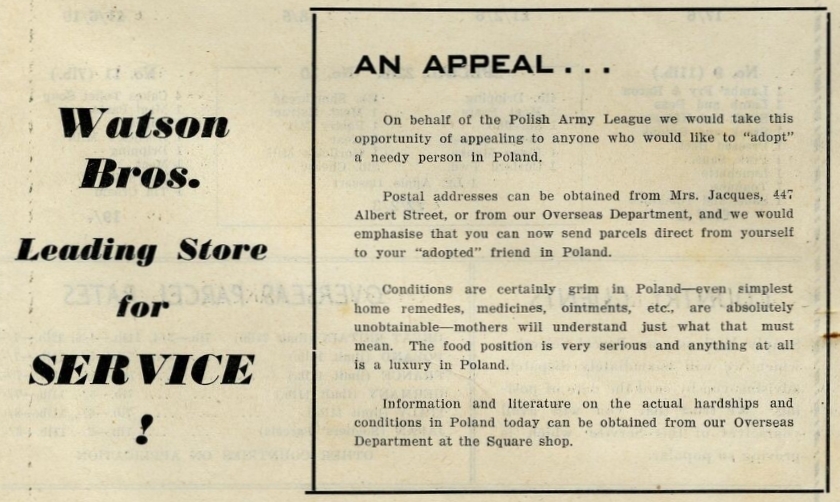

The war in Europe was over, but Ann Jacques’s work was not: Polish soldiers wrote about their destitute relatives in then-communist-controlled Poland, and she responded by appealing for people to donate good, used clothing. In 1947, the appeals for help extended to medicines, and Mrs Field suggested the PAL “take some steps” to meet the costs. The women supported the Voices for Poland appeal that appeared in New Zealand newspapers.

They initiated the help of the overseas parcel service, Watson Bros, and took out more advertisements:

_______________

By 1947, the British army commandant of the Pahiatua camp, Major Finney, apparently forwarded any translations he received to the Polish Army League, telling Mrs Jacques that there was no-one in the camp “able and willing to do them.” It is not clear whether that was true or not, but Mrs Jacques forwarded them to Mr Sledzinski, who had left the camp by December 1945 after a “change in control.”71

Mr Jan Sledzinski, had arrived in New Zealand from England the week before the children, as the camp’s delegate of the Polish Ministry of Social Welfare and Ministry of Education. He had been a school inspector before the war, had served in the Polish army in Scotland, and had volunteered for the Royal West African frontier forces. Before arriving in New Zealand, he had worked at a Polish army college in Britain. He also regularly helped the women of the PAL with packing, translating, and writing in Polish any letters that the committee needed to send to the Polish commanders.72 In a letter to the editor of the dominion in May 1946, Ann Jacques set out his extensive military credentials, and said that he was a “great friend” of the family.

The Third Carpathian soldiers’ paintings and cartoons travelled to Auckland, Nelson, Christchurch, Napier and Whanganui, while Ross Co. in Palmerston North displayed the souvenirs and gifts in one of its large shop windows.73

The war in Europe had ended, but Poles continued to contact Mrs Jacques. In April 1947, she mentioned facilitating a request for help “adopting” about 20 Polish children then in Romania. It is not clear whether this was an appeal for pen-pal friendships or for physical help, but “many” letters kept arriving at 447 Albert Street, Palmerston North, asking for help of various kinds.

On the Polish Army League’s sixth anniversary, the manawatu standard mentioned that the league’s original purpose of sending parcels and letters to Polish soldiers had been replaced by “an equally worthy one—the sending of parcels of food and used clothing to soldiers’ destitute relatives in Poland.”74

Ann Jacques’ last sentence in the PAL minute book:

“All appeals are met with the best of my ability.”

_______________

Ann Kathleen Jacques appeared on the front page of the manawatu standard in January 1994, as an acknowledgement of her 100 years, and her work in her community and WW2. Photograph: Graeme Brown.

Ann and William Jacques remained in contact with the Holender children into adulthood. They continued to support the Palmerston North SPCA, and other charities, and loved going to the cinema, theatre, and ballet. William took up bowls while Ann gardened, and revealed her competitive streak at flower and gardening shows.

Her diaries are full of clippings and her opinions of world events and politics, and her letters to the editor show that she continued to stand up for those she felt were being mistreated. She remained generous with her time and her possessions—she had a hand in organising the flowers and intricate table layout for Queen Elizabeth’s dinner during the Royal visit to Palmerston North in 1954.

Ann’s garden became her solace when her adored brother, Michael, died unexpectedly on 15 March 1953. William died in August 1979, aged 78.

Ann lived to be 100, and received a congratulatory telegram from the same queen she saw in 1954. She died in August 1994, and is buried at the Kelvin Grove cemetery.

© Barbara Scrivens, June 2023.

ANN JACQUES’ DIARIES HAVE BEEN SOURCED FROM THE PALMERSTON NORTH COMMUNITY ARCHIVES, THROUGH MŌ MANAWATŪ HERITAGE, AT THE PALMERSTON NORTH CITY LIBRARY.

UNLESS OTHERWISE CITED, PHOTOGRAPHS ARE EITHER FROM THE JACQUES FAMILY COLLECTION, OR THROUGH THE MŌ MANAWATŪ HERITAGE ARCHIVES.

MANAWATU STANDARD EXCERPTS FROM PAPERS PAST, WERE SOURCED THROUGH THE NATIONAL LIBRARY OF NEW ZEALAND, TE PUNA MĀTAURANGA O AOTEAROA, COPYRIGHT STUFF LTD, UNDER CREATIVE COMMONS BY-NC-SA 3.0 NEW ZEALAND LICENCE.

ALL OTHER NEWSPAPER EXCERPTS, ALSO THROUGH PAPERS PAST, WERE SOURCED THROUGH THE NATIONAL LIBRARY OF NEW ZEALAND, TE PUNA MĀTAURANGA O AOTEAROA.

ENDNOTES:

- 1 - I use the single apostrophe, because the Polish citizens kidnapped at gunpoint by

Stalin’s Secret Police from eastern Poland in the early stages of WW2, and sent to forced-labour facilities in the USSR,

had done nothing that warranted an amnesty.

See Missing Humanity at https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/missing-humanity/ - 2 - Manawatu Standard, 12 May 1941, page 8, MAYORAL ELECTION,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MS19410512.2.83.1 - 3 - Manawatu Standard, 14 May 1941, page 6, MUNICIPAL ELECTIONS,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MS19410514.2.28.4 - 4 - Manawatu Standard, 16 May 1941, page 4, MUNICIPAL ELECTIONS,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MS19410516.2.13.3 - 5 - Manawatu Times, 8 May 1941, page 6, NEWS OF THE DAY,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MT19410508.2.32 - 6 - Fielding Star, 6 December, page 4, PERSONAL,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/FS19281206.2.14

and

Manawatu Standard, 6 December 1928, page 6, MASSEY COLLEGE; FIELD HUSBANDRY WORK; MR WA JACQUES CHOSEN,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MS19281206.2.43

and

Manawatu Times, 6 December 1928, page 6, PERSONAL,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MT19281206.2.19 - 7 - By Nan Kinross, 2017.

- 8 - Manawatu Standard, 7 December 1929, page 15, Women’s World,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MS19291207.2.128 - 9 - Manawatu Times, 11 March 1930, page 7, Paddy’s Market for PN Garrison Band,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MT19300311.2.48 - 10 - Manawatu Standard, 14 June 1932, page 10, SANDON,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MS19320614.2.111

and

Manawatu Standard, 30 January 1933, page 2, YORKSHIRE,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MS19330130.2.25 - 11 - Manawatu Standard, 4 November 1931, page 7, The Spring Show,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MS19311104.2.58 - 12 - Manawatu Standard, 19 September 1932, page 10, SPCA, MASSEY COLLEGE,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MS19320919.2.121 - 13 - Manawatu Standard, 4 March 1933, page 2, PARADE OF PETS, SPCA CARNIVAL,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MS19330304.2.21 - 14 - Manawatu Times, 21 May 1929, page 4, SPCA ANNUAL REPORT; PUBLIC SUPPORT LACKING,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MT19290521.2.30 - 15 - Manawatu Standard, 27 May 1930, page 5, PALMERSTON NORTH SPCA,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MS19300527.2.51,

and

Manawatu Standard, 29 August 1930, page 11, WOMEN’S WORLD,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MS19300829.2.91 - 16 - New Zealand Electronic Text Collection, THE HOME FRONT, Volume II, Chapter 21, WOMEN

AT WAR,

https://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-WH2-2Hom-c21.html - 17 - Manawatu Standard, 5 August 1940, page 2, Advertisements, Column 3,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MS19400805.2.32.3,

and

Manawatu Standard, 3 December 1940, page 8, THE PERSONAL TOUCH,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MS19401203.2.95 - 18 - Manawatu Times, 1 August 1940, page 8, Large Number of Ladies Walk Out, NEW COMMITTEE

TO BE FORMED,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MT19400801.2.97.1 - 19 - Manawatu Standard, 9 August 1940, page 9, WORK FOR REFUGEES,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MS19400809.2.126.5 - 20 - For more information on hussifs, see

https://thedreamstress.com/2015/11/a-lucky-sixpence-hussuf-and-what-are-hussuf-or-housewives/ - 21 - Ibid, Manawatu Standard, 3 December 1940.

- 22 - Manawatu Standard, 1 September 1941, page 7, PDC NAVAL BALL,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MS19410901.2.97.3 - 23 - Manawatu Standard, 10 October 1941, page 7, ROSEMARY CLUB,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MS19411010.2.100.4 - 24 - Manawatu Standard, 14 October 1941, page 4, REQUIESCAT IN GLORIA,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MS19411014.2.31 - 25 - Manawatu Standard, 15 October 1941, page 6, Rotary Visit,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MS19411015.2.27 - 26 - For other Poles who arrived in New Zealand in the 1870s and 1880s, go to our Early Settler database,

https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/search-settlers/ - 27 - Alice Ann Dysaski married Robert Ernest Haig in 1944. (BDM)

- 28 - Manawatu Standard, 31 October 1941, page 7, United Guild,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MS19411031.2.103 - 29 - It is not clear which newspaper interviewed then-Professor Wodzicki, because so many ran the

same story. This account from the New Zealand Herald, 26 April 1941, page 12. POLISH CONSUL,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZH19410426.2.121 - 30 - Manawatu Standard, 28 May 1941, page 6, SCENES IN POLAND,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MS19410528.2.28

and

Evening Post, 23 June 1941, page 9, PERSONAL ITEMS,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/EP19410623.2.98 - 31 - Press, 26 April, page 8, Personal Items,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/CHP19410426.2.41 - 32 - Manawatu Standard, 28 November 1941, page 7,

WOMEN’S WORLD,

and

POLAND’S TRAVAIL,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MS19411128.2.99.2 - 33 - Manawatu Standard, 20 December 1945, page 3, POLISH ARMY LEAGUE,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MS19451220.2.14 - 34 - GC Tennent, “Pukekura,” Horoeka, RR4, Dannevirke, The Work of the Polish Army League,

Manawatū Heritage. - 35 - Polish Army League minute books, page 1.

- 36 - Manawatu Standard, 20 December 1941, page 2, ROSEMARY CLUB,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MS19411220.2.12 - 37 - This photograph was taken by Elmar studios, 459 Main Street, Palmerston North, in May 1942, and archived by Manawatū Heritage.

- 38 - Manawatu Standard, 17 January, 1942, page 6, POLISH ARMY LEAGUE,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MS19420117.2.106 - 39 - Manawatu Standard, 19 January 1942, page 6, Untitled,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MS19420119.2.93 - 40 - Evening Post, 1 October 1941, page 8, READY FOR WAR,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/EP19411001.2.72 - 41 - For more detail about the Soviet ‘deportation’ of Polish civilians into the USSR, see MISSING

HUMANITY,

https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/missing-humanity/ - 42 - Here again, I used the single apostrophes because of the incorrect terminology so often still used: one has to be a foreigner to be deported from a country; the Poles were removed from their own country.

- 43 - Evening Post, 12 November 1941, page 9, GALLANT POLES, BATTLE CONTINUES, INDEPENDENCE

DAY,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/EP19411112.2.85 - 44 - PAL minute book, page 86.

- 45 - See Blue Skies, Green Grass, and Warmth,

https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/blue-skies/ - 46 - Minutes, Inaugural meeting of Polish Children’s Hospitality Committee, Tuesday 24 October 1944, page 4.

- 47 - Minute book, page 53.

- 48 - Thanks to Manawatū Heritage,

https://manawatuheritage.pncc.govt.nz/item/3b9a996b-c235-4700-8568-84885c384d73 - 49 - See The Language of Children,

https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/the-language-of-children/ - 50 - Ibid, The Language of Children.

- 51 - Pascoe, John Dobree, 1908-1972: Photographic albums, prints and negatives.

Crowd greeting Polish refugees on their train journey to Pahiatua from Wellington. Alexander Turnbull Library,

Wellington, New Zealand, Ref: 1/2-003644-F.

http://natlib.govt.nz/records/32058568. - 52 - Manawatu Times, 17 February 1945, page 3, Little Poland Comes To Palmerston North,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MT19450217.2.15 - 53 - PAL minute book, page 66.

- 54 - Manawatū Heritage,

https://manawatuheritage.pncc.govt.nz/item/983e8030-14a4-4167-b8b6-6e1e65fe15d6 - 55 - Manawatū Heritage,

https://manawatuheritage.pncc.govt.nz/item/038033dc-bb82-4813-b850-d56b22f7dad4

(Henryka cut off by original photographer.) - 56 - PAL Minute book, pages 68 & 69

and

Manawatu Standard, 8 June 1945, page 3, Untitled,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MS19450608.2.27.1 - 57 - Manawatu Standard, 20 December 1945, page 3, POLISH ARMY LEAGUE, FINE RECORD OF

WORK,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MS19451220.2.14 - 58 - PAL minute book, page 76.

- 59 - Ibid.

- 60 - PAL minute book, pages 79 & 85.

- 61 - PAL minute book, page 85.

- 62 - The National Patriotic Fund Board notice is minuted on page 84, and the cutting from an unnamed newspaper is on page 86.

- 63 - PAL minute book, page 87.

- 64 - PAL minute book, page 88. The source of the cutting is not stated, but would have come from either of the two local newspapers.

- 65 - J Pobóg-Jaworowski, History of the Polish Settlers in New Zealand, CHZ, “Ars Polona” Warsaw, 1990, Appendices 3, 5, 14, 19 & 24.

- 66 - Newspaper clipping from PAL minute book, page 98.

- 67 - British War office plan for the dispersal of Polish 2nd Corps units assigned to Resettlement camps in the

UK. The 1947 Polish Resettlement Act is available through:

http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/Geo6/10-11/19/enacted. - 68 - For more about the various Polish Resettlement Camps in the UK, see:

http://www.polishresettlementcampsintheuk.co.uk/ - 69 - PAL minute book, page 64.

- 70 - Manawatu Standard, 14 December 1946, GIFTS FROM POLES, (digitised copy not available but cutting from the minute book, page 93)

- 71 - PAL minute book, page 93

and

Ibid Pobóg-Jaworowski, page 199. - 72 - Several newspapers ran the story of M Jan Sledzicki’s arrival.

Evening Star, 27 October 1944, page 5, YOUNG POLISH EMIGRANTS, CAMP CMMANDANT ARRIVES,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/ESD19441027.2.78

and

Minute book, page 75. - 73 - PAL minute book, page 93.

- 74 - Manawatu Standard, 13 December 1947, page unknown,

Clipping in Minute book, page 97.