Halina Kuźmiuk Aman

FITTING BETWEEN THE REVOLVING DOORS

by Barbara Scrivens

Halina Kuźmiuk loved the salami sandwiches that her mother gave her for school lunches. The girls in Halina’s class thought they were smelly. She did not understand their liking for tasteless cucumber sandwiches on thin, white bread.

“Back then New Zealand was very English. I found it hard to fit in. There were so many subtle differences. What I thought at home was very normal, wasn’t normal for the Kiwis.”

Born in a displaced persons camp in Germany in 1945, Halina was used to getting along with people from many nations, but the girls in her class at St Mary’s Catholic school in Christchurch made her aware that she was in a group of one.

“The cultural differences were pretty obvious. Our beliefs were different. Our way of eating was different. The way they spoke and thought was totally different from what I was brought up with, and I felt out of place. It was not only the language, it was the lifestyle and even the clothing. It took me a long time to adjust, to get older and slowly begin to be a Kiwi, to fit in.

“The nuns were very strict. They had rulers and hit you on the knuckles. Sister Patrick, Irish, taught me how to speak English, and I stayed on the Manchester Street side of the school, a co-ed, until Standard 4—you didn’t have to pay until about then. I then went on to the Columbo Street side, which was a private girls’ high school.”

For the first five years of her life, fitting in was not an issue. In DP camps in post-war defeated Germany, everyone arrived from elsewhere. During the last days of the war in Europe, the allies had freed about seven million people from prisoner-of-war camps, labour camps and Nazi concentration camps. The victors then divided Germany into three zones administered by Britain, America and Soviet Russia. The United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) and many other charitable organisations took care of the traumatised refugees and their legion of complicated needs. Later, the International Refugee Organisation (IRO) and the World Health Organisation (WHO) took over the UNRRA’s responsibilities.

Halina’s father, Paweł, had spent five years as a prisoner-of-war in Germany. Germans had captured Halina’s mother, Irena née Buraczynska, in the first few months of the war, and sent her to work for a Gestapo officer.

Paweł Kuźmiuk before his capture by the Germans during their invasion of Poland in WW2.

Halina does not know how her parents met. They married in Glűksburg, Halina was born in Lűtjenburg, and stamps at the backs of photographs show Bergedorf and Flensburg, a DP camp in the British Zone of immediate post-war Germany. Her father had no desire to return to a Poland that had been gifted to the Soviets in 1945 by its apparent allies, Britain and the USA. That same deal left his pre-war home in Kobryn, in eastern Poland, absorbed into the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic.

At the outbreak of WWI, Kobryn had been part of Russian-partitioned eastern Poland for at least 123 years. Despite the Russian government, the Kuźmiuk family managed to retain their Polish language and customs, and lived quietly off their land. At the outbreak of WW1, however, the Russian authority sent such “hostile and untrustworthy” Poles who had avoided Russification to Siberia. Paweł’s father, Nicefor, died there of typhus but Paweł, his mother, Katarzyna, two brothers and a sister survived six years’ exile. Once the new eastern frontier of Poland was established after the 1919–1920 Polish-Soviet War, the balance of the family returned to Kobryn.1

Katarzyna and her children rebuilt their lives. Paweł matriculated and trained as a radio technician. When the Germans invaded Poland on 1 September 1939, he immediately enlisted into the Polish army and left home, like so many others, to protect his country from the enemy in the west. The 1932 Polish-Soviet non-aggression pact should have protected Poland from its enemy in the east.

When the Soviets broke that pact on 17 September 1939, local Soviet sympathisers took revenge on their Polish neighbours and murdered many of them, including Paweł’s mother and younger brother. Only when he was liberated from his prisoner-of-war camp, did Paweł find out that his younger brother died defending their mother as marauding men shot them both.

_______________

Irena Kuźmiuk did not tell her daughter much about her life during the war, or the years immediately afterwards, but she would slip in the occasional comment, like how people got to know the makes of the aeroplanes by the sounds of their engines.

Irena was born in Kutno, about 130 kilometres west of Warsaw, and was 18 when the Germans invaded Poland. Polish forces south of Kutno made a counter-attack on the Wehrmacht on 9 September 1939 in a battle named after the nearby Bzura river. The Poles were defeated when the Germans brought in reinforcements three days later, but they delayed the blitzkrieg’s advance on Warsaw. Kutno itself remained unaffected by that battle but became a German target on 16 September 1939, when the Wehrmacht started bombing the railway station, trains, and houses throughout the district.

The Germans captured Irena’s brother shortly after they occupied Kutno.

“They took him to a concentration camp. He came back home but it wasn’t many months, and he died.

“That was before my mum was caught. They grabbed her off the street and sent her to Germany. She had no way of saying goodbye to her parents, or to her sister, Kazia, who was 14.

“She had to work for a Gestapo officer, look after his children, three of them, I think, one a little girl. She said the mother was okay, but the father was a proper so-and-so. Mum was so proud of the fact that she was able to steal a quite large sterling silver spoon, her own little so-called revenge. Feeling that she had fooled him made her so gleeful. She gave me that spoon before she died. There is something about it.”

_______________

In the Flensburg DP camp, Paweł chaired a committee that looked after the Poles’ welfare. In 1950, after he and Irena had applied for immigration to the USA, he found out that the hellenic prince bound for New Zealand needed one more family to complete its passenger list, and changed his mind about waiting for a berth to America. He was keen to leave the limbo behind and take his wife, Irena, and daughter to a new life.

“I don’t remember anything about the camp at all. My mother used to say I was a very sickly child. I even had TB as a baby. The thing that saved my life was her mother’s milk. She had a huge amount of milk and used to give it to other babies too. She was a great cow. The TB affected my eyesight and my hearing, but her milk saved my life.

“I know that when they were in the camp, they got given parcels from the Americans. Mum said that she used to take the cigarettes and the coffee, sneak out to the German villages, where the people were hard up as well, and do a bit of wheeling and dealing in exchange for better food and clothing for me. The Americans put in things like nylon stockings and chocolates, luxuries for everyone at the time.”

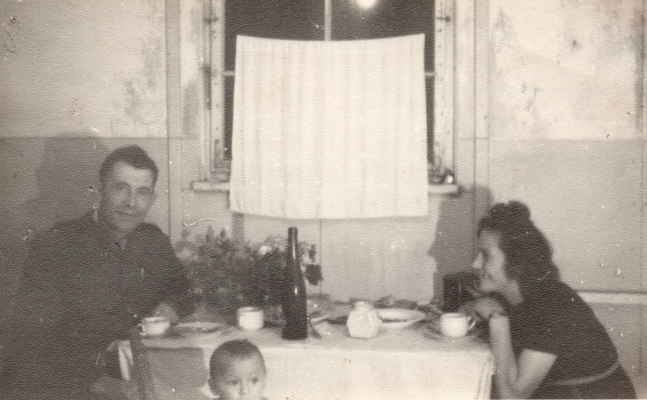

Paweł, Irena and baby Halina at their accommodation in one of the displaced persons camps in British-controlled post-war Germany.

With so many nationalities at the DP camps in post-war Germany, people tended to use German as a universal language, and their children were schooled in German from kindergarten age.

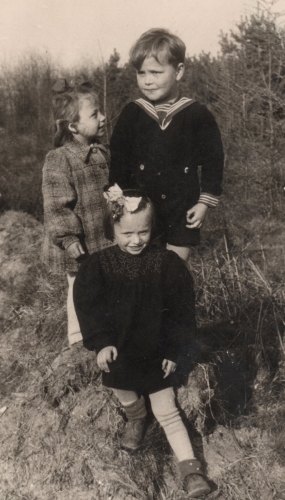

Some of the children and carers at the DP camp in Flensburg, which held Lithuanians, Ukrainians, Balts, and Yugoslavians as well as Poles, all refugees who refused to return to their Soviet-controlled post-war countries. Judging by the photograph below, Halina may be the child on the far right.

The Kuźmiuk family at the Flensburg DP camp in the British zone of immediate post-war Germany. Paweł , a radio technician, had a job as a camp administrator.

The back of this photograph is stamped Flensburg. Halina, left, fondly remembers the boy, Paweł Niszczak, who travelled with his mother on the hellenic prince. She does not know the other girl.

Under the IRO’s resettlement agreement with New Zealand, the hellenic prince left Germany via the Terpitz camp and the port of Bremerhaven on 5 September 1950. It arrived in Wellington on 18 October 1950, a Wednesday. Poles (373) and Polish Ukrainians (81) made up the bulk of its 975 passengers. More than 200 originated from the Baltic States and others were from then-Yugoslavia, Hungary, then-Czechoslovakia, and Russia. Ten declared themselves stateless.

The hellenic prince, seen here at the Wellington wharf in 1950, after carrying 975 continental European refugees from displaced persons camps in Germany to New Zealand.2

Passengers off the hellenic prince in Wellington. The photographer caught Halina and her mother on the far left.

Like other WW2 refugees, those from the hellenic prince took trains to Pahiatua, the refugee camp recently vacated by the last of the 838 Poles, mainly children, who had arrived in 1944 after surviving Soviet forced-labour facilities in the USSR.3 After a few weeks, the Kuźmiuks travelled to Christchurch and their assigned accommodation, the Gainsborough Hotel in Bealey Avenue.

“We were all different nationalities in that hotel. We were given 10 shillings and expected to carry on.”

The Kuźmiuks outside the Gainsborough Hotel in Bealey Avenue, Christchurch.

The Kuzmuiks shared their first Christmas in New Zealand with other continental European refugees at the Gainsborough. Halina is in front on the left: “I was always a bit of a poser.” At the back right is Józefa Konieczna, whose bequest in 1980 started the Polish Charitable & Educational Trust in Christchurch.

A Scottish family, the Williamses, invited the Kuźmiuks to spend Christmas Day with them. Paweł had met the father during his first job on the city’s rubbish trucks.

“They invited us to their house, but it was really hard for my parents. They couldn’t speak English and Christmas back home was a huge thing.”

Paweł retrained at the Polytechnic Institute in Christchurch and started working at the State Hydro, where he remained through its name changes—the Department of Electricity, the New Zealand Electric Division of the Ministry of Energy, the New Zealand Electricity Corporation, and Electrocorp—until he retired in 1971.4

At State Hydro, Paweł was befriended by a man called Jolliffe, who also lived in Bealey Avenue.

“He found us rented accommodation on the corner of Montreal and Conference Streets. We lived there for many years, and when my parents got enough money, we bought the house next door in Conference Street, number 10, so the furniture went over the fence. We were there for many, many, years. It was a lovely old house.

“I’m sure we were about the only Poles in Christchurch then because my parents associated with all kinds of nationalities, Latvian, Czechoslovakian. Some of the Polish soldiers married Germans, like the man who moved into our rental on Montreal Street. Some people couldn’t accept that. The way of thinking at that time was that they were betraying their country by marrying German women.

“Even when the young ones, the 1944 children, moved here to high school, we were always a very small Polish community, but we stuck together, regardless of anything.

“My mother used to entertain a lot. She was a very social person and forever cooking. I remember during the communist era [in post-war Poland], a lot of pianists and mountaineers came to New Zealand, and Mum used to entertain them. The alpine people loved our ice-cream. They would roam around the house with these two-litre tubs under their arms and carry on talking while eating this ice-cream. I’ll always remember that. It was just so vivid.

“They came to Mum because she was about the only Polish person anybody knew who would entertain anyone. People passed the word around, or we went to a concert and she’d invite them to our house. That would have been in the’60s, because we were more comfortably well-off by then.

“So when these famous people visited New Zealand—infrequently—they came to our place. They had to be catered for somewhere, and Mum loved it. We were all craving to know about our own country, but they didn’t tell us much. We wanted to know what was really going on there, but they were always very, very wary of what they said. A lot had joined the Communist party for what it could give them.

“When we had the Polish orchestra here, we saw the terrible class distinction in Poland. There was a background of great social injustice. When Mum entertained them—sometimes we would have a gathering of 20 people—one [social class] didn’t know how to react to the other, because they’d never done it. They would not mix. They didn’t know how, because they weren’t allowed to back home, whereas here, everybody was equal. They played together in the same orchestra but away from that, the upper class wouldn’t talk with anybody who was below them. They wouldn’t communicate at all. Some of the people in the orchestra were engineers, for instance, and they stuck to their own level of people.”

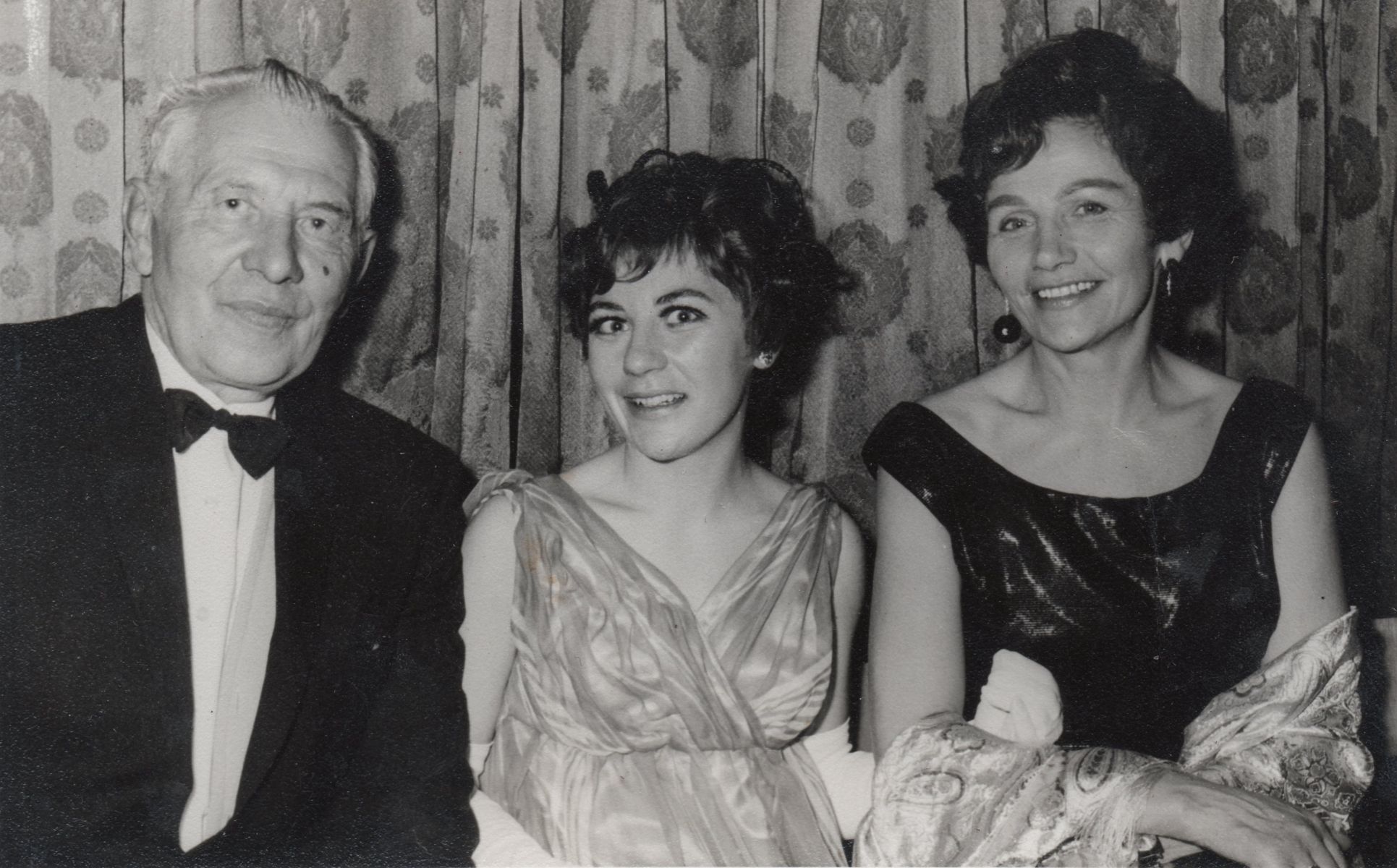

The Kuźmiuks at a Winter Gardens ball in Christchurch in the 1960s.

“I remember a very famous Polish pianist, I think he lived in France at the time. Mum entertained him here and said I should play the piano for him, because I had been playing for quite a few years. Mum thought I had potential. He sat there while I played, and smiled. He was very polite.”

The fact that their house was so often full of people, however interesting or exciting they were, did not go down well with Halina.

“I actually hated it, because I was ignored. Mum was always too busy working and entertaining, and being an only child, I was on my own quite a lot—and that really annoyed me.

“It was like a revolving door. At home, I had all the rich Polish culture because I was very fortunate to have both parents from the same country and we spoke Polish at home all the time. Their way of thinking and being at home, culturally, was confined to our house. As soon as the door opened and I went outside, I had to adjust to the Kiwi way of life. It was like a revolving door. As a young child, I didn’t know which way was right and which was not right, or which way to go. I wanted to fit in one way as well as the other way, and I really didn’t know which was the correct way.

“And even at my age now, I’m still not there. I still feel divided. I fit in more with the Kiwi way, because that’s what I’ve become through friends, and I can understand them, but I’ve still got that inbred pull of the Polish connection.”

_______________

As the Pahiatua Children’s Camp sent its older charges to high schools around New Zealand between 1945 and 1949, some filtered into the then-named Sacred Heart and Xavier colleges, adjacent to the Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament in Christchurch.

“Mum had friends in Wellington—there were so many Poles there—and the word got round that there was a kind Polish lady in Montreal Street. Two or three of the Polish girls would arrive on a Sunday. They were older than me, because they were in high school. I remember their school uniform, black stockings and black gymslips. It was mainly girls, because they were boarders. The boys who went to Xavier were normally allocated out to other families.

“We were central to the [Christchurch city] square, so they walked up or biked. Everybody rode bikes. We didn’t have a car.

“It would usually be the same ones, because there weren’t that many of them. Alina Zioło and her sister, Danuta, used to come,5 and I remember Józefa Wegrzyn. Mum would have made them something like gołąbki.

“Mum felt sorry for them, because I don’t think they were happy at the school. I understood from Alina that, because they weren’t paying—the government was paying—the nuns made them do work like polish the floors, that sort of thing. We just got them out for a while.

“Some of them stayed in Christchurch, some married and moved away, and other Poles arrived.”

The Poles who arrived in Christchurch in the 1950s had no idea of its Polish heritage, or that Poles from Prussian-partitioned Poland had landed in Lyttelton in 1872.6 Once more of the post-war Poles settled in Christchurch, Paweł and Irena organised gatherings. In the 1980s, when another wave of Polish immigrants arrived in their city, the Christchurch Polish Association took on a more formal mantle.

Lidia Janiec arrived in New Zealand with her husband, Piotr, and children Zofia and Antoni aboard the dalkirk bay in 1949 and soon became another stalwart of the Christchurch Poles.

“I went to her funeral. I was going to wear a gold bracelet. It had twisted—for weeks I had tried to straighten it but couldn’t get it right. I put it on the table and decided that after her funeral, I would take it to the jewellers. I came back, and that bracelet was straight. I always reckoned it was her!”

From left: Lidia Janiec (née Popowicz), Irena Kuźmiuk, Regina Nilon (née Piatkowska) and Regina Burda (née Tymińska), who all settled in Christchurch in the 1950s, seen here in the 1990s. Lidia Janiec died in 2009, Irena Kuźmiuk in 2006, Regina Nilon in 2013, and Regina Burda died in February 2020 aged 95.

_______________

Irena’s sister, Kazia Buraczyńska, survived the war and remained in Poland. Halina had met her aunt in 1965, during a three-year OE (overseas experience) based in London. She went with a friend and together they took on temporary jobs through employment agencies so that they could travel as much as possible.

“We hitch-hiked most of Italy—we loved Italy—and got the boat from Bari to Greece. We did all of Europe, from Holland, Belgium, through a bit of Germany, and I went back home to Poland on my own. That was the first time I met my aunty Kazia.”

Halina had no fear stepping behind the Iron Curtain to visit her aunt and her husband at their apartment in Kutno.

“I was safe. I was going to relatives, wasn’t I? My uncle had to report me to the police. You had to have visas everywhere you went.

“Compared with other people, they were quite well off. At that time, depending how many children you had, the apartments were allocated by floor space. A lot of families lived in one room. They’d have a sofa that would be the bed as well. My aunty lived on the second floor, and had a separate bedroom, a separate dining room, a little kitchen, and a little laundry. They had an old-fashioned coal stove with tiny [inlaid] tiles, and used to lug the coal up those flights of stairs.

“There were always shortages. In shops you had to ask the people behind the counters for what you wanted, but it was hardly ever there. In a clothes shop, it was pot luck whether there was anything your size to choose from.

“But the women were fabulous. They could sew. One of my relatives looked at me. She wanted to give me a present. She said, ‘I make bras,’ and suddenly put her hand over my breast to get my size. A couple of weeks afterwards, she gave me this bra. It looked ugly, but it was the most fabulous bra. It fitted me perfectly, and really perked me up. It was brilliant! No underwire or stiffening. I’m not sure what material, but beautifully made.”

Halina met Sam Aman in London and they married in 1967. Born in Aden, Yemen, Sam lived in the same apartment block as Halina. They divorced, but had two daughters, Amira, now living in Australia, and in Christchurch, Leila, whose sons aged nine, seven and five, bring exuberance into Halina’s life.

Halina with her daughters, Leila, left, and Amira.

_______________

After she returned from her OE, Halina persuaded her mother to visit her sister in Poland.

“She was going to catch a Greek ship from Wellington and took the connecting boat from Christchurch the night before—the waihene. Dad wasn’t going to go with her to Wellington but I told him he couldn’t expect her to go alone, even though she had so many friends there, so they were both on the waihene when it sank [in Wellington harbour on 10 April 1968].7

“They survived the sinking, but they lost everything, all their suitcases, and I was annoyed because I had bought them so many nice things from England. They put in a claim but the only bit of money they got was for the cost of the cabin, and what they had there, not what was in their suitcases.

“Mum missed the boat to Poland, but they survived. They stayed with friends in Wellington. A big store in the city gave them clothes, and they bought some. They came home after a few days—on another ferry.

“She went to see her sister the year after, and her sister came here, but Mum had to be very, very careful what she said. There was quite a clash between them, because of the political situation and the communism in Poland, compared to what we had here in New Zealand. Their lives were totally different, and Mum had seen for herself that the conditions in Poland were still difficult, the situation extremely hard.

“Mum worked at Lane Walker at that time. Every Christmas she used to make up packages to send to Poland, with flour and basic household things, and clothes, so they could have a good Christmas.

“They wrote to each other, but they had different ways of thinking; they had nothing in common. They had been such a long time apart, one could not understand the other. Here, we had such a good life, freedom, and we were able to work and achieve something, whereas there, there was nothing—unless you belonged to the Communist Party, then you had a few little benefits. A lot of people joined the Communist Party because of those benefits, not necessarily because they believed in the policies. About 90 percent of the Poles were Catholics, so religion was more important, and that went underground. Kazia’s husband was very supportive of the communists, and when she died, she had a communist funeral.”

_______________

Retirement at 66 did not suit Paweł. He found a temporary job as a linesman, then worked at the Watties factory warehouse in Hornby until he was 74.

“We ate a lot of chicken then! Dad had a great maths brain. They didn’t have computers in those days so he used to keep stock, and he was the only one. When he left, they replaced him with three people.”

While Irena entertained local and visiting Poles, Paweł continued to work for the Polish community in Christchurch. He served as president of its association for several years.

“In those days—the ’60s—people helped one another. If you had a house that needed the driveway concreted, people would help you. You don’t get that anymore. You have to pay for everything.”

Paweł Kuźmiuk and Irena née Buraczyńska, probably on their wedding day in post-war allied-administered Germany.

Irena Kuźmiuk with her granddaughter Leila at Pegasus Bay, on Irena’s 80th birthday on 15 October 2000.

_______________

After WW2, Paweł’s brother elected to remain in their hometown on the Byelorussian side of the 1945 Polish border. His infrequent letters carried the news that their sister had died of natural causes. When his letters stopped altogether, Paweł assumed his brother had died too. Paweł never returned to his birthplace, and died in Christchurch in August 1989. He is buried at Memorial Park in Bromley, alongside Irena, who died in August 2006.

These days Halina continues a close relationship with other Poles in Christchurch, including Alina and Danuta née Zioło, who live nearby. Her revolving door now spins much more slowly, lovingly weighed down with family and friends.

© Barbara Scrivens, December 2020.

APART FROM THE HELLENIC PRINCE AND THE SPOON, ALL PHOTOGRAPHS, FROM THE KUŹMIUK-AMAN FAMILY COLLECTION.

THANKS TO THE NORTH AUCKLAND RESEARCH CENTRE IN THE TAKAPUNA LIBRARY FOR THE LOAN OF AUDIO RECORDING EQUIPMENT.

ENDNOTES:

- 1 - This account of Paweł Kuźmiuk’s life was delivered at his funeral.

- 2 - This photograph was taken for the Evening Post in Wellington, and is archived at the New Zealand National Library, reference number 114/211/11-G.

- 3 - Read the stories of the Pahiatua children:

https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/pahiatua-refuge/ - 4 - From Paweł Kuźmiuk’s obituary.

- 5 - Read the story of the Ziolo siblings:

https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/the-ziolo-siblings/ - 6- Read the story of the early Polish settlers in Christchurch in the story Marshland, The Place Where Flax Grows Profusely: https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/marshland/

- 7 - One of the websites that detail the Waihene disaster:

https://nzhistory.govt.nz/culture/wahine-disaster