Jan Jarka

VANQUISH EVIL BY DOING GOOD

(Zło dobrem zwycieżaj)

by Barbara Scrivens

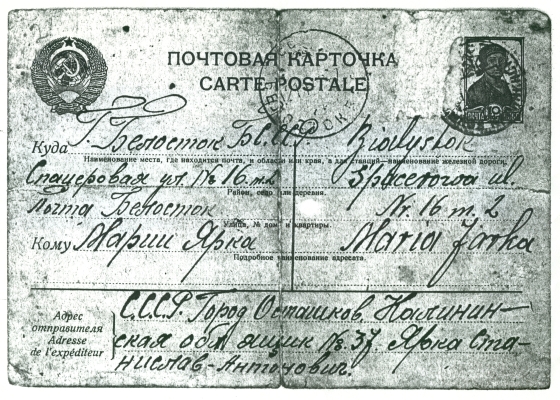

Stanisław Jarka, NKVD prisoner, squeezed 10 extra words into the top left-hand corner of a postcard: “Marysiu jeśli możesz to jedż do rodziców i zabierz rzeczy.” (Marysia, if you can, go to your parents and take everything.)

The postcard was dated 27 December 1939; the location Ostaszków (Ostashkov), a Soviet prisoner-of-war camp. Marysia was his second wife.

Stanisław Jarka with his first wife, Rozalia, circa 1933 and their children, Jan and Jadzia.

In the main body of the postcard Stanisław tells Marysia he is in Soviet Russia, alive and well, and wished her the same. He longs for them all and cannot comprehend why he has not had an answer to the letter he wrote. He does not know where they are, what has happened to them, or if they are still alive. He begs Marysia to write to him, manage the best she can and, if her health allows and provisions are getting depleted, to possibly get a job or sell their things to pay for day-to-day living.

He addresses Marysia as his beloved, sends her affectionate kisses, wishes them all a happy New Year, asks for photographs and for news of parents and other acquaintances. According to the code he worked out with Maria before he left their home in Białystok to find the Polish army in 1939, his mention of Kożuszek (his sheepskin coat), indicated that his situation was dire.

On the left of his name at the bottom, Stanisław crammed in another four words: “Marysia, be faithful to me.” (Marysiu bądż mi wierną.)

_______________

From a thousand kilometres away, Stanisław knew his family would be suffering without his income as a police officer in Białystok.

In Russian Ostaszków—and in the company of men and officers from his Ostrołęka 5th Cavalry Regiment—he may not have foreseen his own imminent danger.

Commander-in-Chief of the Polish forces in the USSR… became concerned that Polish officers did not arrive in the numbers he expected…

Immediately after their invasion of Poland on September 17, 1939, the Soviets set up PoW camps in Kozielsk, east of Smolensk, Starobielsk, near Kharkov, and Ostaszków, near Kalinin (now Tver). More than 22,000 mainly Polish officers disappeared from those camps between April and May 1940.

Their glaring absence at enlistment stations drew suspicion in 1942 from Commander-in-Chief of the Polish forces in the USSR General Władysław Anders. He became concerned that Polish officers did not arrive in the numbers he expected for a new Polish army gathering on Russian soil—part of the Polish-Soviet agreement of 30 July 1941 after Hitler turned on his former ally Stalin.

As a commanding officer who had fought in the first weeks of the German and Russian invasions of Poland, Anders was wounded and captured in Zastówka on 29 September 1939. He learnt about the three PoW camps while in Moscow’s Lubyanka1 prison and after his release was told repeatedly by Soviet authorities that the camps had been “abolished” in 1940—the whereabouts of the camps’ former inmates apparently unknown to their Soviet captors.2

General Anders, from his book an army in exile: the story of the second polish corps:3

The first wave of arrests was that of Polish soldiers taken prisoner by the Russian troops when, in accordance with the alliance between Stalin and Hitler, they made a surprise attack on our rear. Those prisoners were concentrated in the notorious camps of Kozielsk, Starobielsk and Ostashkov, where about 15,000 prisoners, mostly officers, were held, amongst them a number of frontier guards, priests, policemen and members of the judicial service.

In the beginning of 1940 Kozielsk contained 5,000 men, 4,500 of whom were officers. Starobielsk held 3,820 officers and about 100 civilians, cadet-officers and ensigns. Only 380 officers were incarcerated in Ostaszków, the largest PoW camp. Most of its 6,882 inmates were non-commissioned officers who enlisted—like Stanisław—at their country’s time of need.

Anders later calculated that the NKVD released only a few hundred officers from another camp, Griasovietsk.4 Anders repeatedly questioned Stalin and his authorities. All fobbed him off with assurances that the officers would appear, that they had probably escaped and were making their way to the enlistment stations.

The only certain fact was that not one of them could be found, and no news of any of them had been received since March 1940.5

Anders did not know then of the 7,305 other missing Polish prisoners in what is now western Ukraine and western Belorussia.

_______________

Jadzia Jarka, with her blonde hair and fringe, is instantly recognisable sitting in front of her mother among the extended family picnicking either in the woods near their Białystok home, or Czarnowo, where her maternal grandparents lived.

Jan Jarka retained vivid recollections of being woken up at exactly 4.45am on 1 September 1939. The radio announced: “Uwaga, uwaga… preszedł…” (Attention, attention… passed over…).6

Germany had invaded Poland. Jan was nine and Jadwiga 16 months older.

Two things happened in the Jarka household immediately afterwards: Stanisław and their stepmother made the children learn their grandparents’ home address; and Stanisław left home “not as a policeman but as a soldier defending Poland.”

Jan: “The phrase ‘wieś Czarnowo, gmina Goworowo, powiat Ostrołęcki, województwo Warszawskie, Polska’ (village Czarnowo, parish Goworowo, district Ostrołęka, province Warsaw, Poland) became forever etched in my memory.”7

Like English city parents who sent their children to the apparent safety of the countryside during the war years, Stanisław and Maria prepared Jan and Jadwiga. Unlike in England, Poland was already occupied, and there was no ordered evacuation of children.

Jan kept this photograph of his grandparents, Franciszek and Franciszka Puka on their farm.

Today Czarnowo, about 130 kilometres south-southwest of Białystok, is still a one-road village but adjacent to a feeder road leading to the main Białystok-Warsaw highway. Jan spent the first six years of his life there after he developed a lung infection as a baby that was made worse in the “unclean city air.”

This sombre photograph shows Jan as a six-year-old behind Rozalia Jarka’s open coffin in July 1936. She was 26 when she died of a heart attack. Rozalia’s mother prays at her feet and her father stands on the left with his arm around Jadzia. Stanisław's step-mother, Anna, his sister, Janina, and father, Antoni, are to the right.

Jan wrote in a 2004 essay:

“As was the practice in those days, my father soon remarried, as there was an urgent need for a mother to look after the upbringing of two youngsters because my father’s work often required him to be away from home.”

Jan remained a sickly child. His shaved head at this pre-war family outing with stepmother, Maria, was apparently a way to prevent fever.

Jan called his mother’s death his “first tragedy.” Judging by the dates he would have barely had a year to re-acquaint himself with her before she died. Almost as painful as his mother’s death is his memory of what he called his “second tragedy,”—hearing the radio announce the invasion three years later:

“Soon these [German] aeroplanes were all over Białystok, engaged in dog fights, with heavy bombing of railway stations, both passenger and freight, which were not far from our home, and were met by artillery fire from the guns located in our neighbour’s orchard. Within days I witnessed the actual misery of the war when along our street—ironically called Spacerowa [Strolling] Street—the German soldiers marched, for almost a whole morning, Polish soldiers into German captivity. That sight and many others still remains vivid in my memory.

“When the Germans occupied Białystok they transferred all the boys from my school to the girls’ school across the road, making that an interrogation centre for prisoners of war, with daily shots of execution heard by all of us. It was frightening!

“… soon my family had a personal encounter with the enemy when a jeep full of very well-dressed, high-ranking and polite German officers called at our house at No. 16, which was opposite a small park. Having been given the ‘Heil Hitler’ salute, the officers began to enquire where No. 15 was, where we knew some Germans lived. Although it was scary, it was also very thrilling for a young boy. The German officers took me with them to show them the required address and soon returned me, unharmed but loaded with sweets and chocolates, much to the relief of my stepmother and sister.

“After about three weeks most of the citizens of Białystok were lining up along the main street to witness the departure of the Germans and the arrival, within minutes, of the Russians. What a contrast… it is hard to describe.”8

Jan did not see his father among those Polish soldiers but when the postcard arrived from Ostaszków Maria, Jadwiga and he had to accept that Stanisław did not escape capture.

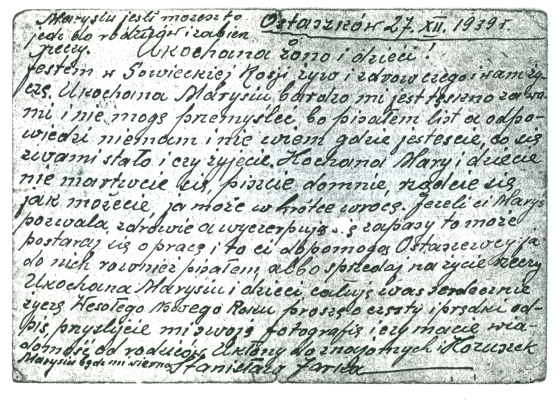

A memorandum written by Laverentii Beria, USSR People’s Commissar for Internal Affairs, and dated 5 March 1940, outlined the spurious reasoning behind the proposed execution by shooting of the mostly Polish officers: Russia’s state archive published the documents in April 2010—marked “Top Secret” and among formerly classified documents on Katyń given to Poland by Russia in 1992.9

To Comrade Stalin:

In prisoner-of-war camps run by the USSR NKVD and in prisons in western Ukraine and Belorussia there is currently a large

number of former Polish army officers, former officials of the Polish police and intelligence services, members of Polish

nationalist counter-revolutionary parties, members of unmasked rebel counter-revolutionary organisations, defectors and

others. They are all sworn enemies of Soviet power, filled with hatred towards the Soviet system.

The POW officers and police in the camps are trying to continue counter-revolutionary work and are engaged in anti-Soviet

agitation. Each of them is just waiting for liberation so as to actively join the struggle against Soviet power…

In total in the prisoner-of-war camps (not counting soldiers and non-commissioned officers) there are 14,736 former

officers, government officials, landowners, policemen, military police, jailers, settlers and spies. More than 97% are of

Polish nationality…

In total the prisons of western Ukraine and Belorussia contain 18,632 detainees (of whom 10,685 are Poles)…

Based on the fact that all of them are steadfast incorrigible enemies of Soviet power, the USSR NKVD deems it

essential:

I. To propose that the USSR NKVD give special consideration to:

1) the cases of 14,700 people remaining in the prisoner-of-war camps - former Polish army officers, government

officials, landowners, policemen, intelligence agents, military policemen, settlers and jailers,

2) and also the cases of those arrested and remaining in prisons in the western districts of Ukraine and Belorussia,

totalling 11,000—members of various counter-revolutionary spy and sabotage organisations, former landowners, factory

owners, former Polish army officers, government officials and defectors—

Imposing on them the sentence of capital punishment—execution by shooting.

II. The cases are to be handled without the convicts being summoned and without revealing the charges; with no statements

concerning the conclusion of the investigation and the bills of indictment given to them…

Stalin signed his agreement to the massacre on the front page of Beria’s memorandum with an emphatic underlining. Below his are the signatures of Politburo members K. Voroshilov, A. Mikoyan and V. Molotov. His aides, Kalinin and Kaganovich, show less flamboyance in the margin.

Author and Reader in Politics at the University of Bristol, George Sanford:10

During April-May 1940 the Starobielsk PoWs were taken by train in almost daily convoys to be shot in the NKVD prison cells in Kharkow and to be buried in a forest park close to the city. Those from Ostashkov were similarly transported to be shot in the NKVD prison cells in Tver and buried in the greatest secrecy at Madnoe [sic], a small village about 20 miles distant. Those transported from Kozelsk were, apparently, shot and buried in one fell swoop in the Katyń forest 12 miles from Smolensk.

_______________

Maria, Jadwiga and Jan remained in their Białystok home until Soviet soldiers rounded them up in the second of four mass expulsions of Polish civilians from Soviet-occupied eastern Poland. Between 1939 and 1941 the number of Poles extracted from Poland by the Soviets grew to nearly 1,700,000. Around 900,000 civilians went by cattle train to northern Russia and Siberia. (See missing humanity for a fuller picture of the train journeys.)

Polish orphanages, under the auspices of the Red Cross… were seen as safe havens for children during the exodus from the USSR.

In a 1996 curriculum vitae Jan mentions nothing but the date—13 April 1940, and their destination—the village of Gregorianki near Pawłodar (Pavlodar) on the north-eastern corner of Kazakhstan. His next entry says that he arrived (przyjechał) with his sister in a Polish orphanage in Ashkabad, southern Turkmenistan in February or March 1943.

Four years later Jan repeated the story, but added that they travelled with “many other Poles.” Today the journey is 3,200 kilometres by road.

After Stalin granted the Poles ‘amnesty’ following the Polish-Soviet agreement (See military timeline, 30 July 1941), thousands of Poles walked away from NKVD forced-labour camps and prisons throughout the USSR. They heard a Polish army was being formed on Russian soil, and were making their way to enlistment stations near Tashkent, Uzbekistan, about half-way between Pawłodar and Ashkabad.

Their stepmother may have accompanied Jan and Jadwiga at first—but she was not with them in Ashkabad, their final stop towards freedom from the USSR. Did she push them on a full train “going to safety”? Was she left behind when she disembarked from their train to hunt for food and water? Did she abandon them? Did she feel the children would be safer in an orphanage?

Polish orphanages, under the auspices of the Red Cross and backed by the Polish government-in-exile, were seen as safe havens for children during the exodus from the USSR.

The Jarka siblings travelled to Ashkabad under the supervision of teacher Wilhelmina Rudnicka. Hers is the only non-familial name on Jan’s 1996 CV. Her two sons, Henryk and Witold, were a similar age to Jan. They shared the journey out of the USSR through the Kopet Dag mountains (Köpetdag Dagersi) that divide Turkmenistan and Iran (then Persia) to Mashhad, Teheran and finally Esfahan (Isfahan).

This photograph, apparently taken in Mashhad, was in Jan Jarka's collection, so it is probable that he is among the children who received their First Holy Communion that day.

Jan’s son, Michael, found this photograph among Jan’s collection. It seems to be a celebration of Święty Mikołaj, the bishop of Myra, whose death on December 6 is celebrated by the giving of presents, although it is doubtful that many “presents” appeared at this Isfahan orphanage of at least 96 children and 13 caregivers. Judging from the facial features of boys and adults, the photograph seems more a record of attendance than a celebration of Christmas joy.

The Polish children and caregivers stayed in a number of mansions and institutions in Isfahan for nearly two years. Jan Jarka kept this photograph, so this is probably where he stayed. If anyone can identify the hostel, please get in touch with us through our home page.

Jan and Jadzia remained in Isfahan for nearly two years and were among more than 700 Polish children and more than 100 of their caregivers invited by the New Zealand government to spend the balance of the war in New Zealand.

In September 1944 those Poles left Persia together, via Ahwaz and Basrah, where they caught the cargo ship sontay—not equipped for passengers—to Bombay. They all appreciated the transfer to the spacious purpose-built troop ship uss general randall, which brought them to Wellington.

_______________

Jan: “I arrived with my sister Jadwiga at the Polish Children’s Camp in Pahiatua with very few material possessions but with great expectations that our stay in this country would be short, World War II would soon be over and we would be on our way home to Poland to rejoin my surviving relatives.”11

Jan with Jadzia in Pahiatua. Below, Zofia Pleciak’s illustration of a Polish wintry scene, which she drew in Jan's autograph book, and below that, Jan 1949–1950.

Polish schooling at the camp ended in 1946 when it became clear that there would not be a free Poland to return to. Jan transferred to St Kevin’s College in Oamaru during 1947, stayed in 1948, and moved to Sacred Heart College in Auckland to finish his university entrance examinations.

In an unpublished section of a story he wrote for a commemorative book about the Pahiatua children, Jan acknowledged Bishop Reginald Delargey, then director of Catholic Social Services for the Auckland diocese, and others who “took our future well-being into their hearts by ensuring that no child entered the work force without adequate and proper academic and/or professional qualifications.”

Jan followed their advice, studied accountancy and remained in the field until his retirement in 1989. Friendships made during this time included the then-solicitor David Lange, who looked after some of the accounting firm’s insurance clients:

“On one occasion when David was Prime Minister of New Zealand we had a private discussion on the need for a closer and confident approach of Polish immigrants towards the local authorities without fear of being ‘black marked.’ The solution lay in appointing Polish-speaking people as Justices of the Peace. On David’s suggestion I approached four of my countrymen, but sadly all declined the offer. Only I was prepared to give it a go; I was directed to see my local Member of Parliament for Manurewa, Mr Roger Douglas, and on 5 April 1990 I was appointed and sworn in as a Justice of the Peace.”12

Jan’s adult life reflected the ties he made in Pahiatua. An active member of the Auckland Polish Association since its inception in 1960, he served several terms as president and vice-president. His second term as president in 1986 coincided with the pastoral visit of Pope John Paul II to New Zealand, when he celebrated an open-air Mass at the Auckland Domain on 22 November.

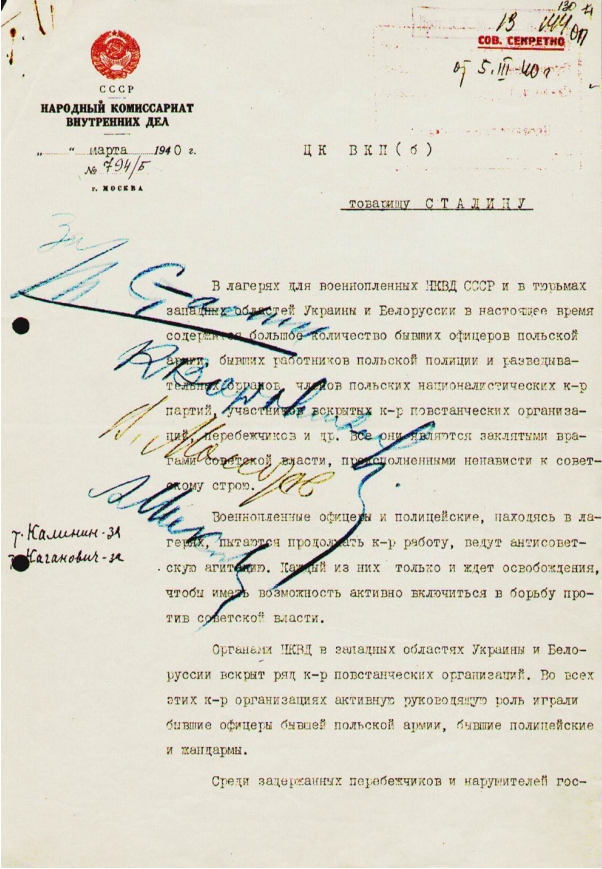

Jan described the “thrill” of being among the Polish community at this time, and of greeting His Holiness in the traditional Polish way—with salt and bread offered on a tray.

Behind Jan at the papal Mass is Pani Cela Zazulak.

“Dad described that event as the highlight of his life,” said Michael. “To present the tray

to His Holiness… a Polish pope…”

Jan did not mention in his essay the amount of organising that went into the Mass-centred event. One of the gifts Pope John Paul II took back with him to Rome, and also on the greeting tray, right, was a Polish prayer book dated 1893 and used by the earliest Polish settlers in Taranaki.

The note “Done and Delivered 4/11/86” on a letter regarding the papal visit marks Jan’s work ethic and his adherence to the values instilled in him by his father in particular:

“I remember a very loving family but very disciplined and well taught in the principles of love, honesty, justice and fair play as well as charity and humanity.”

Long before it became official, the address on his father’s postcard made it clear to Jan that Stanisław was among those murdered in what became known as the Katyń massacre. Jan lived his father’s mantra, encapsulated in a lapel badge he bought on his first trip back to Poland 50 years after he was forced to leave—Zło Dobrem Zwycieżaj—Vanquish Evil by Doing Good.

Jan’s life of involvement with all sorts of Poles and other ethnic minorities resulted in his being awarded the Queen’s Service Medal in June 1993 for services to the New Zealand community. Here he is with his wife, Stella, and his nominee, Stanisław Wolk, outside Government House in Wellington after the ceremony.

_______________

Jan’s “service to the community” started with his increased involvement with Poles in Auckland, which led to his becoming an accredited interpreter/translator and, in 1985, a founding member of the Auckland Ethnic Council, set up to “facilitate the settlement and resolution of problems for new immigrants.”

Jan: “The interpreting work came as a result of an emergency court session, when two Polish gypsies were caught travelling in New Zealand on illegal passports in the late 1970s. The court official, who knew me through my sporting activities, asked me to help out as the gypsies claimed that they could not speak any English. What a shock for them to be faced with a Polish translator so far from home!”13

Besides his work with the Auckland Polish Association, Justice of the Peace commitments, and his local parish of St Anne’s—he was made a Minister of the Eucharist in 1975—Jan made himself available as a translator to the Auckland and Otahuhu district courts and police stations, the New Zealand Immigration Service, the Appeal Authority, Land Transport Safety Authority, Qualifications Authority, Labour Department and Citizens Advice Bureau.

_______________

Growing up, Michael remembers his father repeating often: “I never want you to go through what I went through.” He followed the statement by saying his children needed to know what happened to him and the other Poles.

Michael remembers his father and his Polish generation as:

“In the unforgiving environment of Kazakhstan, it was dangerous to show any sign of weakness. To do so meant death.”

“Impatient to leave behind their experiences of humiliation and deprivation in Kazakhstan. Motivated by a strong will to survive and succeed in civilian life, they wanted to prove to their Soviet captors that they had intelligence, could think for themselves, that they had culture, manners and decency—unlike their Soviet jailers. They would not allow themselves to be beaten into any kind of submission, political or otherwise. In the unforgiving environment of Kazakhstan, it was dangerous to show any sign of weakness. To do so meant death. They learnt the arts of patience, tolerance, humility, making do and endurance, which they put to good use in later life.

“My father leaned a lot on his Catholic faith and the comradeship of his fellow survivors to endure, and they undoubtedly helped him through some of the most difficult and joyous times in his life, such as the birth of his children and the various health problems which afflicted my sisters Rozalia and Elizabeth and me. His apparent super-human ability to be the rock in our family momentarily faltered when my sister Rozalia predeceased him in 1999. He never really recovered from the shock.

“My dad was someone who checked his facts and prepared his cases very carefully before he took any action. Dad was honest in everything he did. He had a typically Polish sense of humour—political and often black.

“For example, when I was a teenager who was friends with two other teenage girls, he gave me a good piece of advice. He said not to two-time them, because it was morally repugnant and would affect my personal reputation, so the best course of action for me was to choose which friend I liked better and remain loyal to that one friend. I did so. Despite my choice later turning out to be a mistake, I did learn a good lesson. Eventually it led me to a wife to whom I have been married to since 2004.

“Dad was a loving, if somewhat traditional, husband but when he was wrong he would accept it and move on.”

_______________

The Polish government acknowledged Jan’s “outstanding contribution to the Polish community in New Zealand” in November 2004, when he was awarded, with several others, the Krzyż Kawalerski Orderu Zasługi Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej (Order of Merit for the Republic of Poland, Knight's Cross).

Jan with Stella, left, and Jadwiga at the Krzyż Kawalerski Orderu Zasługi Rzeczypospolitej

Polskiej ceremony.

Below, Jan's three medals, the QSM on the left and the Siberian Exiles Cross on the right.

The Polish President later acknowledged his traumatic experiences in Kazakhstan with the award of the Krzyż Zesłańców Sybiru (Siberian Exiles Cross). The Polish government introduced the honour in October 2003 for survivors of the forced removals and incarcerations in northern Russia, Siberia and Kazakhstan between 1939 and 1956 who were still living in January 2004.14

_______________

Once he retired Jan was able to show Stella (née Wilkinson) the country of his roots, and rekindle vague childhood memories.

Jan, left, with some of his extended family on his first visit to Poland.

Jan and Stella visited Rozalia’s grave and were given her portrait, left. They also met his stepmother, who returned to Poland in about 1954.

Jan: “On the first visit the [extended family] were very cautious, even standoffish, as they were under the impression that we had come back to claim back our family land and possessions. On the second visit [with Jadwiga in 1996] we were accepted as members of the Jarka clan and welcomed everywhere.”

Although Jan had become naturalised in New Zealand in 1962, he was determined to claim his Polish citizenship and gain Polish passports for his two surviving children, Michael and Elizabeth. (Rozalia junior, born with a heart condition, died in 1999.) Jan's Polish citizenship came through in November 2000 and the passports followed.

Jan never gave up looking for his father’s remains. The International Committee of the Red Cross answered his 1990 query with a note admitting that the list of exhumed victims in the mass graves at that time was not exhaustive.

A newspaper obituary, The Unsung War Hero, lay among his papers. It told how former British secret service agent Ron Jeffrey “knew too much” about the Katyń massacres and was ostracised in England after the war, apparently thanks to “the treachery of Kim Philby and other high-ranking communist agents entrenched in the British system.”15 Ron migrated to New Zealand. (Jan may have included the obituary for a second reason—in 1987 Ron lost the Mangere parliamentary seat to David Lange.)

Jan died in 2008 and did not live to see the official recognition of his father as a victim of the Katyń massacre.

Two years later Stella received a commemorative booklet marking the 70th anniversary of the murders and listing the 55 officers from the Ostrołęka area.

Stanisław’s fate was confirmed in one line:

Zamordowany przez NKWD strzałem w tył głowy w Twer, w 1940r. (Murdered by the NKVD with a shot to the back of the head in Twer in 1940.)16

© Barbara Scrivens, 2016

Updated September 2017.

ALL PHOTOGRAPHS COME FROM THE JARKA COLLECTION.

Michael Jarka's story, Visiting Poland Under Martial Law is on the LATER ARRIVALS page.

ENDNOTES:

- 1 - Russian spelling Lubyanka, Polish Łubianka.

- 2 - Anders, Władysław, Lt-General, An Army in Exile: The Story of the Second Polish Corps, page 48. Originally published in 1949, reprinted by The Battery Press, Nashville, ISBN: 0-89839-043-5.

- 3 - Ibid, page 66.

- 4 - Ibid.

- 5 - Ibid, page 76.

- 6 - From an essay Jan wrote in June 2004. (An edited portion is in the publication, New Zealand’s First Refugees: Pahiatua’s Polish Children, Polish Children’s Reunion Committee, 2004, pages 115–116.

- 7 - Ibid Jarka essay.

- 8 - Ibid Jarka essay.

- 9 - This extract from the BBC website page, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/8649435.stm, 28 April 2010.

- 10 - Sanford, George, The Katyn Massacre and Polish-Soviet Relations, 1941-43, Journal of Contemporary History, 2006, pages 41 ; 95, DOI 10.1177/0022009406058676, page 95.

- 11 - Ibid Jarka essay.

- 12 - Ibid Jarka essay.

- 13 - Ibid Jarka essay.

- 14 - Anyone who thinks they or their relative may be eligible for the Siberian Exiles Cross and would like a copy of an application form should contact me through the get in touch link on our home page.

- 15 - New Zealand Herald, 28 September 2002, under the column Last Word, page unknown.

- 16 - From Ofiary Zbrodni Katyńskiej 1940 Roku Związane z 5 Pułkiem Ułanów i Ziemia Ostrołęką, (Victims of the Crimes of Katyń in 1940 related to the 5th Cavalry Regiment and Ostrołęka) printed by the Ostrołęka Historical Society, 2010.