Jan Kaźmierów

The first time I visited Jan Kaźmierów in September 2018, he gave me an amaryllis, which produced a magnificent set of huge red blooms within weeks. It bloomed again this spring, reminding me of his kindness, and a generosity that extended beyond his time and patience, to arms full of whatever vegetables or fruit happened to be ripe in his garden.

I had grown to know Pan Jan by sight. Alone at a meeting of the Auckland Polish Association several years ago, I asked him whether I could sit next to him, and repeated the request at several other meetings.

I first went to his home in Auckland after finding out that he had not been receiving the compensation he was entitled to from the Polish government, as a result of his time at the hands of the Soviets in the USSR in WW2.

The biography he wrote for the application was so comprehensive, I knew I needed to interview him more fully about his family’s forced removal from their small farm in eastern Poland by the Soviets in 1940. Thanks to a father who could read Cyrillic, and older brothers, Pan Jan was able to reconstruct the family’s journey, passing through Kiev and Moscow to the Arctic regions of northern Russia, across the Urals, and to Uzbekistan, where he and two of his brothers parted with their father and older brother.

Pan Jan’s mother, three sisters, and eldest brother died in the USSR, and he never saw his father again, but he holds no bitterness about what happened to him then, or that the current Polish government rejected his application for compensation. Instead, he has undertaken to find out as much as possible about what led to his fate, and the fate of so many millions of other Poles, during WW2.

I thank Pan Jan and his wife, Dorothea, for their time and patience during several days when maps, papers and audio equipment took over the dining room at their Auckland home.

—Basia Scrivens

CROSSING BORDERS, TRAVERSING HISTORY

by Barbara Scrivens

Not many people can say they have blown into the face of an NKVD officer, and lived.

It happened during Jan Kaźmierów’s second—and last—day at a school run by an NKVD forced-labour facility in the Archangielsk region of northern Russia. Jan, not yet seven, had been following his mother’s instructions, perhaps ill-advised considering Soviet soldiers had only months earlier ripped the family from their home in eastern Poland, and transported them there as “anti-Soviet elements.”1

“At the school they gave you lunch—some type of soup and a hunk of bread—something to eat, but it came at a price: On the very first day, we were sitting at the long table when suddenly, two Russian soldiers arrived with rifles. They gave a big patriotic speech, stating that the Krasnaja Armiya, the Red Army, was the people’s friend, liberated people, had never lost a battle…

“I knew it was nonsense, because my father had told me about Piłsudski, and how Poland won the war with the Russians in 1920, but of course I didn’t say anything.

“What I liked was that they gave us those rifles to play with, take apart, oil them. I was thinking, ‘This is great,’ when suddenly another guy arrived—thick, thick glasses, black hair all combed backwards. He would go to a kid, and he would say, ‘There’s no God.’ He was picking on the Polish kids especially. They put us in the Russian school to brainwash us. That guy came up to me, leaned over, and said:

‘Nema boha.’ [Russian: There is no God.]

‘Nie, nie, jest Bóg, jest.’ [Polish: No, no, there is a God, there is.]

‘Who told you that?’ he said.

‘My mother told me.’

‘Your mother is a stupid woman. She doesn’t know what she is talking about. There is no God. You show me where’s God.’

“So, when my mother came back from work, from the forest, and asked me what the school was like, I told her about that guy, the one who told me to point out where was God. She listened and she told me, ‘Tomorrow, when he asks, you go right up to him and say, God is duch [ghost], and you do this:’ She blew towards me.

“Next day, he came to the classroom again, came straight up to me, leaned across the table again, right in my face, and said:

‘Are you ready to show me where’s God?’

‘My mother said God is—and I blew on him—duch.’ I blew right in his face, and he jumped back.

‘Du-rak!’

“That’s ‘idiot’ in Russian. He left me alone after that, but mother told me and my older brother Tom that the next time the Russian officers came to collect us to go to school, both of us should hide.”

_______________

Few of the Poles in the hundreds of forced-labour facilities, and prisons scattered around the USSR could have escaped the continual Soviet indoctrination. The Soviet guards repeatedly told their Polish prisoners to forget about Poland, that they were there “forever.”2

That February, Soviet soldiers had removed more than 200,000 Polish civilians from their homes in eastern Poland—mainly farmers and their families, like those in osada Biała, where Jan was born on 15 August 1933.

Biała was not a large osada in eastern Poland, only 11 Polish families, but their presence niggled some Ukrainians in neighbouring Zwiniacze.

Ten of the Polish men from Biała had fought the Bolsheviks during the 1919–1920 Polish–Soviet War. They held low ranks—seven privates, a lance corporal and a lance sergeant—and had accepted the option from the new Polish government to farm about 11 hectares each.

Jan Kaźmierów was the fifth child of Franciszek and Maria (née Bułyga3 ) Kaźmierów. Franciszek’s family came from Kołodno, about 25 kilometres east of Białystok. Their Biała farm lay to the immediate east of their Ukrainian neighbour in Zwiniacze, and about five kilometres from the Horyń river, which wove in and out of the border with Ukrainian SSR.

Zwinacze, here in the north-western corner, with the Horyń river in the south. Biała was south-east of Zwinacze, where the contours widen.4

“There were always squabbles with the Ukranian neighbour over the paddock my father kept for the horses and cows. There were no fences, just a strip of land between the properties to walk along and, when we went to church or something like that, the neighbour put his cattle in our pasture.

“All those arguments… and when the Russians moved in [after the Soviet invasion on 17 September 1939], he appeared with a red band on his arm, to get into their good books.

“At that time the weather was beautiful. We had been seeing German planes, bombers mainly, flying from south to north. My father said that they were bombing the town called Łuck, north of us. Łuck happened to be the place where the Polish government in Warsaw evacuated.”

Germany invaded Poland on 1 September 1939. After it became clear that the Germans would capture Warsaw, some of Poland’s core government officials moved to Łuck, a logical choice: The Second Polish Republic had established an airport there in 1937, and it was the base for the 13th Kresowy Light Artillery Regiment and the Łuck National Defence (Poland) Battalion.

The governmental Poles arrived on the evening of 7 September, but the Germans soon found out, and bombed the town on 11 and 14 September. The Polish government officials left, heading south towards the then Polish-Romanian border.5

“My oldest brothers, if they heard any noise from motor vehicles, ran to the road to have a look, and saw a lot of Polish officials heading south, some in civvies and some military. It was a shock for us to see them go.

“We’d seen Polish Air Force planes before the war started, then the German planes, and we knew the Russians had moved in when we saw the Russian planes. They were not bombers. They were fighters, two or three of them, obviously the latest produced by the Soviets. They looked like illusions, beautiful, white. You couldn’t mistake the red star low on the fuselage and the tail.

“I’ll never forget it. The weather was perfect. The sun was shining. They flew almost at the tops of the chimneys. I saw the face of the pilot above me distinctly. He leaned out of the window and threw out leaflets.

“The older boys and the men formed a guard, because the Ukrainians at that time were setting Polish homes alight.”

“My father could read Cyrillic. The leaflets said that Red Army was marching into Poland to ‘liberate’ the people from the Polish ‘lords,’ the ‘oppressors’—Russian propaganda, excusing them from what they were actually doing.”

The Soviets invaded Poland from the east on 17 September 1939. Soviet Minister of Foreign Affairs Vyacheslav Molotov, who had signed the Nazi-Soviet non-aggression pact the previous month, announced on Soviet radio that day that, “Poland had become a convenient field for any contingency and surprises which might create a menace to the Soviet Union.” The Soviet government could not, he said, “remain indifferent to the fate of kindred Ukrainians and White Russians living in Poland, who even previously were nations without any rights and who now have been abandoned to their fate.”6

Jan: “Suddenly, Ukrainian hooligans started to attack the Poles and their farms. To be safe, we used to vacate our home at night, and stayed in houses a bit farther into the Polish settlement. The older boys and the men formed a guard, because the Ukrainians at that time were setting Polish homes alight. That’s when stuff from our property went missing. They were helping themselves.

“Once the Russian army moved in and instilled their authority—their NKVD police—that stopped. The hooligans disappeared.”

While at osada Biała, Franciszek Kaźmierów had joined the military reserves. He had answered a call up to a military camp in Łuck, but that “sort of fell to bits” under the speed at which the German and Russian armies took over Poland in September 1939.

_______________

The early generations of Franciszek Kaźmierów’s family had lived in Kołodno, about 500 kilometres north of Biała, with a different surname—Rozdolski.

In 1795, the empires of Prussia, Austro-Hungary and Russia divided Poland between them for the third time in 23 years. In Russian-partitioned Poland, the 1863 Polish Uprising against the Tsar led to 17 months’ of battles between insurgent Poles and their allies, and the Russian army. The Tsar’s continually replenished and growing army overcame the Poles, with no such resources, in April 1874, and the Russians began to de-Polonise the area.

They sent thousands of Poles to Siberia—a long-preferred place of forced exile—abolished Polish institutions, replaced senior Polish administrators with Russians, confiscated land, and revoked serfdom.

The Tsar’s army conscripted Jan’s paternal grandfather, Piotr Rozdolski, and changed his name to a less Polish-sounding one.

The same army conscripted Franciszek during WW1, but as soon as he had the chance, he enlisted in the Piłsudski Polish Legions, under the leadership of General Władysław Sikorski, and fought first in northern Poland, then in eastern Poland against the Bolsheviks in the 1919-1920 Polish-Soviet War.

“Piłsudski used his cavalry to go behind their lines, attack them from there, and chop up their supplies.”

“My father was in the cavalry, so they were mobile. Piłsudski used the cavalry to get to the back of the Soviet’s lines. That strategy won the [Polish-Soviet] war.

“The Poles had to do something drastic. Once they attacked the Bolsheviks, they went right to Kiev, but according to Piłsudski, the Russians were retreating faster than the Poles could catch up with them. Once the Poles got to Kiev, they were hoping to organise other lines, to push on, but the Soviet army got re-equipped—manpower—and started to counter-attack, and because the front was so long, when the Poles were trying to form a barrier of a certain area, the Bolsheviks would come along from behind and outflank them. The Polish army at that time had something like 250,000 men and the area that they had to patrol would have been something like 1,000 kilometres. The Poles didn’t have the manpower to match the Russians.7

“In the end, when the Russians had pushed back as far as Warsaw, Piłsudski, from his experience against them in WW1, knew that behind their lines was empty space, with hardly any Russian troops. Piłsudski used his cavalry to go behind their lines, attack them from there, and chop up their supplies. That’s what won the battle, the Miracle on the Vistula. Also, the Poles used to listen to the Russian field radios and jam them. They broke the code. They knew the movements of the Russians, the Bolshevik forces, because they were reading the orders from Moscow.”8

_______________

Schools closed soon after the Russians invaded eastern Poland in September 1939, so the entire Kaźmierów family remained home during the autumn and winter. Władysław, Jan’s eldest brother, was born in 1923, Piotr in 1925, Anna, whom they called Hanka, in 1928, and Tomasz in 1931. Jan was followed by sisters Bronisława, or Bronka, in 1936, and Katarzyna, or Kasia, in 1938.

“NKVD and Russian army officers used to come to our farm with our Ukrainian neighbour, the one with the red band on his arm. They measured the land, and counted the animals, and I saw that neighbour of ours pointing out to them what we still had in stock, what they hadn’t already helped themselves to when we were away. The [NKVD] officer would offer us kids lollies, trying to get more information from us. My father told us, ‘Do not talk to those people.’”

Pristine summer weather turned into one of the most severe winters in Europe. At the Kaźmierów farm, icicles about half a metre long hung from the eaves of buildings.

“There was a beautiful picture of Our Lady of Częstochowa. They chucked it down, and they tramped on it, cracking the glass.

“Early one morning, our dog started to bark, because there were people outside. My oldest brother opened the door, and there was a Russian soldier pointing at him with a rifle with a bayonet about a metre long, ordering him, ‘Get back inside.’

“The soldier with the bayonet stayed outside. About four others came into the house—one was an officer—and they had an NKVD with them. I’ll never forget him. He had a very tidy uniform: white jacket and white cap, peaked, with a blue band around it. He was in charge.

“Apparently all the Polish families in our settlement had soldiers at their places at the same time.

“My mother was crying. My younger sisters were crying. Hanka joined in. The soldiers started to ransack the house. All of us had baptism pictures of our name saints on the walls. The first thing they did was chuck them down, and stomp on them. There was a beautiful picture of Our Lady of Częstochowa. They chucked it down, and they tramped on it, cracking the glass. I thought, ‘Crikey, we’re going to get a lightning strike!’ I was terrified. Nothing happened. I was disappointed.

“Later on, I asked my mother, how could it be that they were chucking all the pictures down like that, and there was no lightning strike? She said, ‘In God’s time, they’ll get punished.’ Bóg tego nie zapomnie.

“That NKVD officer walked out of the house, and the Russian soldiers suddenly stopped being nasty to us. I saw my father starting to talk to the Russian officer, in Russian. My father then told us that we had to move out, pack up. I asked him how we were going to travel? My father said, ‘On the train.’

“A train! I was so excited. I was imagining the same train that my oldest brother was on when he travelled one school holiday First Class to Warsaw, on an American Pullman that the Polish Railways used. First Class…

“They gave us one or two hours to pack. Because my mother was in shock, my father took a blanket and made it into a sort of sack, and threw stuff into it. We didn’t have much, but we still had a ham and some bread that my mother had made, and butter and eggs. My mother had a glory-box, about three feet in length, maybe about 18 inches in width, and a couple of feet high. She had some beautiful boots, high-heels, like in cowboy times, with laces, and he put them in, plus some of his gear—stuff like pincers and his hammer—because he was a blacksmith by trade. That helped us a lot later.

“They started [to clear the Polish families] from the far side of the settlement, and they had so many sledges, one per family. We happened to be the last ones. I don’t know why, but there was one sledge left over, still empty when it got to us, so my father asked the driver if he could put that glory-box on it. The driver said yes, so I think my father gave him something.”

The Russian soldiers escorted the Polish families to the Krzemieniec railway station 15 to 20 kilometres from Biała. Jan remembers the sledges ploughing through “a couple of feet of snow.”

“Every morning the guards would check who was dead, and who was still alive.”

“There were already people waiting at the station, and Soviet soldiers. Just as we got to the station, there were Polish women, apparently from the Red Cross. They had a pot of hot milk, and they were giving it to the kids. I remember distinctly that we were each given a cup of hot milk to drink.

“They packed us into the train, so many people in each carriage—an animal carriage. The disappointment! It was a train, but it wasn’t that beautiful First Class Pullman. It was an animal train, a wooden carriage, with a hole in the floor for the people to use as a toilet, and a little stove to boil water. I don’t know how we could boil water when we had no facilities, no wood, but my brother Piotr, the second oldest, for some reason had picked up a pot from home, not a heavy pot—more like a milk can—but it meant we could boil water.

“There was a bit of a window, about half a metre wide and the same tall, with a couple of rods through it, for ventilation for the animals. Each wagon had a Russian soldier guarding it. It had a sort of walking board at the back, where the soldier would go and inspect that no one was trying to escape. Every morning the guards would check who was dead, and who was still alive. One morning my oldest brother looked up, saw the soldier, and asked him if he could scoop the snow from the roof for the water. The soldier gave him permission.

“Sometimes when the train stopped, the guards allowed people to jump off and get some snow, or do their thing beside the train. But this time it was still in motion, early morning, and it wasn’t going to stop. My brother could get almost half his body out, if someone lifted him up, and he scooped up the snow into that pot, boiled this snow, and that was the water. There was straw on the floor for the people to sleep on, and they burnt the straw in the stove.

“I didn’t take much notice of what the others were doing, because my father put my brother Tomek and me next to the sliding door. It had a gap of about five centimetres, and he told us to count the trains going past, to distract our attention from the cries and other stuff going on inside the carriage.”

_______________

Although many Poles remember the 10th, a Saturday morning, as the date linked to their forced exile from Poland in February 1940, a list of departure dates compiled from Russian records shows only the 1st and the 5th of February.9

Despite the clinical way in which the NKVD organised the operation, it would have been a feat of supreme order if all the trains had left the various railway stations along the length of eastern Poland on the same day, or even two. To those ripped out of their homes, knowing the exact date would have been a minor consideration compared to the enormity of their situation.

The NKVD recorded the Kaźmierów’s train leaving on 5 February 1940 with 1,432 Poles. It was bound for Kotlas in northern Russia.

It formed part of the first of four mass ‘deportations’10 of around 900,000 Polish civilians to northern Russia and Siberia. Two more mass removals occurred in April and June 1940. Hitler inadvertently curtailed the fourth, in June 1941, when he ordered his troops to cross the Nazi-Soviet line created by them during the 1939 invasions, and ploughed through Soviet-occupied Poland towards Moscow. (For a fuller explanation of the methods that Stalin used to remove what he called “anti-Soviet elements” from Poland, and conditions on the trains, see Missing Humanity.)

_______________

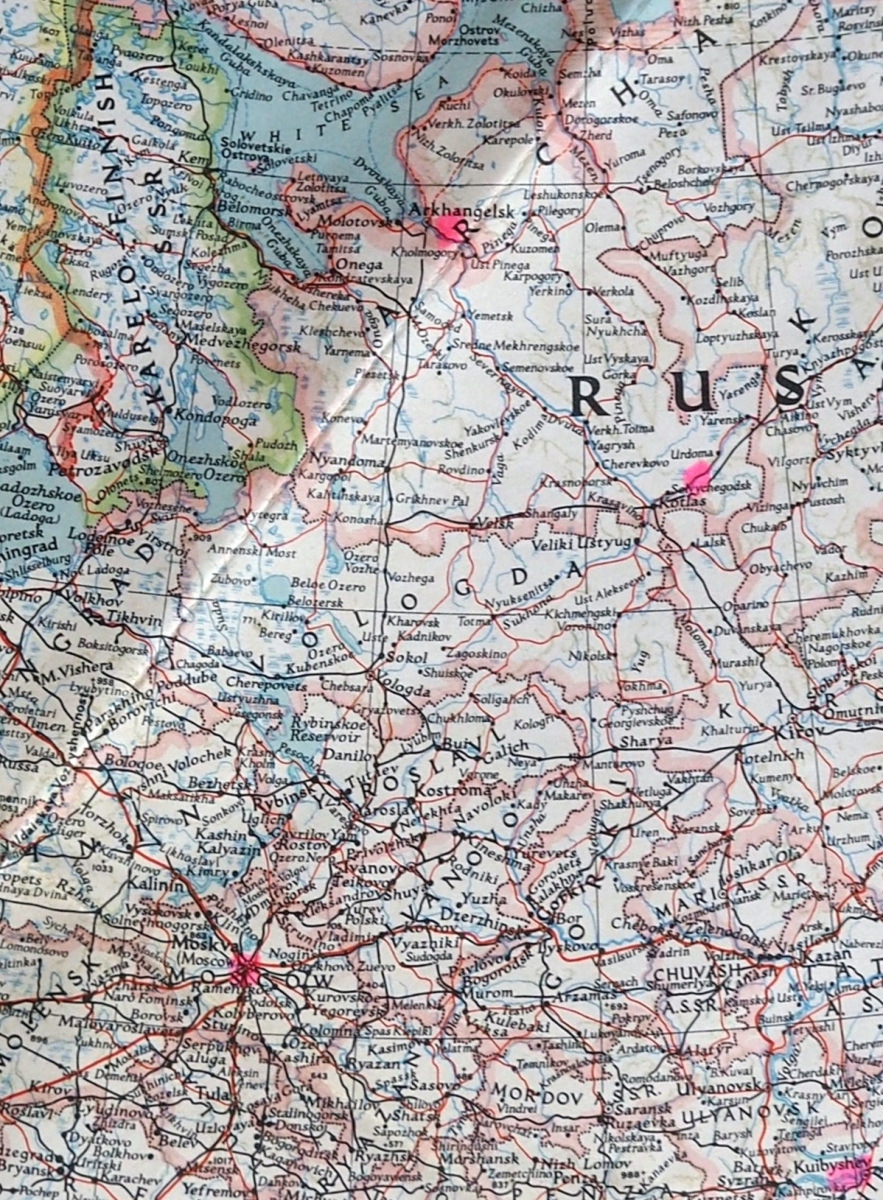

This section from the National Geographic Magazine’s Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

map, dated December 1944, shows the Soviet's presumptive grip on Poland before the official hand-over by her so-called Allies

in 1945. Poland’s pre-war boundaries in orange and apricot colours are confused with the borders of Ukrainian and

Byelorussian SSR.

Łuck, here spelt Lutsk, north of Krzemieniec, is above the letter “U” in the south of the map. Jan marked Kiev,

Poltava, Orel and Moscow, and their destination, Kotlas in the far top right.

“We stopped in Kiev early one morning. I don’t remember if we were taken from that train and put in another one, but I do remember we had to get out of the carriages, and the boys, my oldest brothers and a few others, were cleaning up the mess. I was under the impression that we were put onto another train to carry on, and that that train went back Poland.

“I later figured out our next stop was Poltava. It wasn’t a proper railway station, more like marshalling yards. There were about three layers of rails, and we were right at the top. We must have been there all night, when suddenly they opened the doors, and the soldiers told us to get some fresh air and do our toiletry. We saw three trains parked. The people from the lowest train started to shout to other people. I remember one guy said, ‘We are returning from Charków.’ [Kharkov, 185 kilometres east.]

“The kids were looking around, and we saw one carriage at the very bottom—no roof, and soldiers huddled up against one corner. I asked my father, ‘Who are those people?’ He took a look and he said, ‘They are Polish soldiers. They are all frozen dead.’ He took a loaf of bread and threw the loaf down to them. It hit them. They didn’t move.

“When the other Polish people saw what was happening, they called the Russians bandits and bastards, and suddenly the guards saw what was happening, put us back on the train, and locked us up again. When they opened up after an hour or so, all those corpses were gone. Things like that stick to the memory.”

As the train made its way through Russia, its whistle alerted its passengers of major stations. Franciszek got Władysław to put his head out of the window to look at the signs and write them down.

“My father said, ‘Oh, that’s Orel,’ and then Moscow. The [Moskva] river was on the right side of the train, and there were the red brick walls of the Kremlin. My father lifted me up to have a look and told me that’s where Stalin lives.

“We arrived there in the morning, and they took us off the train, and marched us into the main station. I remember that as if it was today. The Moscow station is, of course, big. There were huge portraits of Lenin, I think Karl Marx, and Stalin, and two big clocks showing different times.

“We were taken into the station, under guard, to the Russian bania—the public baths—because we were in the train maybe two or three weeks, and we must have smelt like cattle. Then they put us on a passenger train—the reason for the bania.

“There was a soldier with a bayonet outside the window, and inside they were talking Polish. That soldier was stamping his feet, because it was mighty cold, and with the butt of his rifle, he was writing something in the snow. I asked my oldest brother what he was doing, and my brother looked at him and he said, ‘He’s a Pole.’ He could hear us, and he was trying to communicate with us in the snow. A lot of Polish people never got out of Russia after the 1917 Bolshevik revolution.”

Although the train’s destination was Kotlas, there was no direct rail route from Moscow in 1940. Trains running north through Moscow went as far as Archangielsk on the White Sea. The Dwina river was the only transport link between Archangielsk and Kotlas, the region’s south-east rail link. Other cattle transports carrying Poles went east from Moscow, towards Kirov, then north to Kotlas. From there, the railway veered to the north-east “straight as a die” to the arctic coal mines of Vorkuta.

The black lines on this map show railways from Moscow, here in the lower right, towards Archangielsk on the White Sea. (By the time this map was published, the link between Konash and Kotlas was finished.) Jan has marked Moscow, Archangielsk and Kotlas in pink. The red line that runs parallel to the Dwina river signifies it is an “important route.”

“The trains used to travel night and day, so we were not aware of where we were going, except where we could read the [names of the] stations during daylight.

“We stopped in a forest quite a distance outside Archangielsk, although we didn’t know where it was at the time, on a track that was part of a loop. Suddenly another train arrived from the opposite direction, from Molotovsk [now Severodvinsk]. It was a beautiful white train, beautiful. All the Russian trains were grubby but this one was white like snow.

“That train went into the loop and stopped beside ours, so we jumped out. We were still under guard, but it was a train—no sliding doors to lock. My oldest brother went to the other train to investigate, maybe buy some food from them. My father went as well.

“Through the door I could see a tier of three bunks with wounded soldiers. My brothers were looking at the train and at the hub, which had a Polish eagle with PKP [Polska Kolej Państwowa, Polish State Railways] on it. That was the American Pulman train that they used in Poland—the train I imagined we would be taking—converted into a hospital train.

“According to my father, who had looked inside and had a few words with those soldiers, they were Russians returning from the Finnish front. My father told us that a lot of those soldiers had self-inflicted wounds. They probably got shot when they got back to Russia, because self-inflicted wounds were a signal that you tried to desert.”

_______________

The guards on the Kaźmierów’s train off-loaded the surviving Poles, who waited several hours before sledges arrived.

“It was still snowing and terribly cold, and from the railway, on that sledge, we went through the forest onto the open river [Dwina], where there was no protection at all from the winds. At that time of the year, the rivers were used as highways. They were saying there was two metres of ice.

“…the snow started to thaw out, and there was a big rush of people re-burying the corpses, because they were being exposed.”

“Once we arrived at the place—some vacated labour camp—the Russians were offering us hot drinks. I don’t know what it was. Not Milo, some bloody thing. My father passed me a cup and said, ‘Pass it to Bronka.’ My mother was sitting with the baby. She had a blanket around her. My sister Bronka was next to her, then me and my older brother Tom. The oldest brothers had to walk besides the sledge. Hanka was on the other side of mother.

“I tried to give Bronka the drink. She didn’t respond, so I nudged her and said, ‘Bronka, here’s a drink.’ She still didn’t respond, so I turned to my father and said, ‘She’s asleep.’ He looked at her, and realised that she was frozen. He took her out and rubbed her with snow to get her circulation going, but that was it. She had died on the journey.

“My father and brothers made a coffin. I wasn’t present when they buried her, but they buried most of the people that died at the side of the river. The ground was frozen, so they went as far they could through the ice, put the coffins there and covered them up. We got there about the 3rd of March, according to the Russian reports. I remember one day, my father and brothers arrived from the forest, when suddenly the snow started to thaw out, and there was a big rush of people re-burying the corpses, because they were being exposed.

“In spring, we were allowed to go near the river. Because we were higher, we could see Archangielsk quite a way in the distance, three or four kilometres. We must have stayed at that place until maybe April or May, when the snow thawed out, and they shifted us to Kotlas by ferry, and then Solwyczegodzk. We went down the river on this Mississippi style of cowboy boat, a paddle-steamer with wagon wheels pushing through the water.

“Kotlas was quite a big town, mainly timber industries. They put us on a wooden cart with a horse, and drove us maybe 30 kilometres. There were a lot of marshes in that area.”

_______________

The NKVD seemed to have deliberately divided the residents of even the smallest Polish osada:

NKVD records show no other osada Biała families besides the Kaźmieróws in Charitonowo, a forced-labour facility in Archangielsk’s Solwyczegodzk oblast, which listed 709 Poles.11

The NKVD sent the lance-sergeant Adam Gabryk, his wife, Marta, and their children, Janina and Stanisław, to Diedowka in the Molotov oblast (now Perm) in the southern Urals.

Franciszek Iłczyszyn was also from Franciszek’s home-town of Kołodno. He, his wife, Praskiewa, and son, Andrzej, ended up in one of the most remote of the Archangielsk forced-labour facilities, Jareńga, which held 175 Poles about 100 kilometres north-east of Charitonowo.

The Soviets transported five Biała families even farther north, to Utkym, which held 336 Poles, including two members of the Kudrzyński family, which Jan remembers as cousins: Mieczysław born in 1922 and his mother, Franciszka. Mieczysław’s father, Rafał, like Franciszek Kaźmierów, had apparently followed orders to report to the Polish army in September 1939, but had not returned. His name does not appear on the same NKVD list as his wife and son.

Other Biała families sent to Utkym were:

–Józef and Anna Krawiec, both born in 1899, and their children, Julian, Rozalia and Władysław.

–Antoni and Anna (née Dobrowolska) Mazur and three children. Tadeusz was 13 in 1940, and Edward two, when the Soviet soldiers removed them from their home. The NKVD recorded another unnamed Mazur child who did not survive its birth, on 1 April 1941, although that may be the date of record and not reality.

–The Róż family of 10 included two brothers, the lance sergeant, Wojciech, born in 1883, and Józef, born in 1900, their mother, wives and children. The NKVD records show that Anna Róż, born in 1862, survived until her release in September 1941. The children are identified through the fathers—Wojciech’s were Stanisława and Maria, and Józef’s were Anna, Tadeusz and Stefania—but the records do not show which of the brothers Apolonia and Maria Róż married.

The Biała family names Kaleuch, Koźlak and Stróżów remain elusive.12

_______________

The Kaźmieróws knew nothing of their Biała neighbours’ fates, and arrived in Charitonowo, where the Soviets expected them to work to their deaths.

“We were assigned barracks. People 12 years of age had to work, and my older sister, Hanka—she was 12—was assigned to the big, workers’ canteen. My oldest brothers and mother and father were assigned to work in the forest. My older brother, Tomasz, and I were assigned to go to the Russian school. I went to what they called a ‘diet sad’ [detskij sad], like a kindergarten for children under seven. They put Tomasz, in his second year of primary school in Poland, back to the first year in the Russian school.

“Soviet guards were always checking on the people, how many were still alive, because they had to go to work, and the kids were taken to the school. After a while, the school gave up on us, but some kids kept going, because they were getting food. You can’t blame them for that.

“We were lucky we had older brothers, because every one of those people who were working got rations. They had to produce a certain amount of work. If they didn’t do that work, their rations were cut, or their pay was cut, and they were always supervised when they worked in the forest. There was, of course, rye bread, real black bread. It was mixed with a lot of sawdust and stuff like that, maybe quarter of it husks.

“They had so-called shops for everybody, us and the local Russians from the village. If someone heard about, say, a supply of clothes, there would be queues of people in the line. By the time they got to the front, there was nothing left. It was similar with bread. Soap was unheard of.

“We had forgotten all about the glory-box until we were settled in Charitonowo and suddenly it appeared. It was one of those miracles, but don’t forget that in Russia, if there was something official, posted, being sent through the office, it had to be done, otherwise, they would be against the wall.

“The only thing that was missing, according to my father, was the bottle of vodka. My mother’s beautiful boots were there. She traded those boots for food. One of the Russian officers’ wives took a liking to them, because you couldn’t get leather boots in Russia at that time—not the public anyway—or clothes like those that the Poles were selling, superior to anything in the Soviet Union.

“Our mother gave Tomasz the job to look after our youngest sister, Kasia, and I was promoted to be the cook for the family. Can you imagine? A seven-year-old kid. There was hardly anything to cook—potatoes and maybe some cabbage, stuff like that, but she would tell me what to do. My job was to keep cooking until they arrived from the forest.”

The commandant at Charitonowo recorded Maria Kaźmierów’s death on 5 April 1941, and Hanka’s two days later. It is not clear whether Maria had reached her 37th birthday, or Hanka her 13th.

“I can’t remember the dates, but I do know that my mother developed terrible rheumatism in her arms from working in the snow in temperatures up to minus 30 degrees, and I doubt any of them had anything like gloves. I know she died in terrible pain, and Hanka died of typhus.

“People in the locality were dying from anything infectious, like typhus, anything spread by lice. We were all riddled with them. No matter how much you washed, if someone in your room got lice, you were going to get lice, and lice spread disease.”

The rest of the Kaźmierów family managed to survive until the 1941 autumn, when they heard they could leave Charitonowo.

_______________

Weeks after Hitler’s invasion of Russia, Stalin announced an amnesty for the Poles he had incarcerated in the USSR. General Sikorski, then Prime Minister of the Polish government-in-exile and Stalin’s Soviet ambassador in London, Ivan Maisky, brokered the details and signed the document on 30 July 1941.

The agreement included the Poles forming an army in Russia, made up of former inmates from the NKVD forced-labour facilities and prisons. Franciszek Kaźmierów heard that anyone wanting to enlist should head towards Kuibyshev (now Samara) in southern Russia, where there was a Polish embassy, and a Polish military mission.

“I was just getting over typhus. I was very weak, but I remember that my father said that we have amnesty, we’re allowed to travel.”

As well as the lingering disease, Jan’s night blindness gummed up his eyes in the mornings, and he was distracted further by a knee injury he acquired soon after the family started walking along the road from Charitonowo to Kotlas. Piotr (Peter) had been carrying Jan, still too ill to walk. After a while, Piotr put Jan on one of the tree stumps and stepped away to recover his breath. Jan does not know why he tried to jump off the stump, but he did, and landed on his knees, one on a piece of wood sticking from the ground.

A horse and buggy on the way to Kotlas picked them up.

“My head was still spinning from the typhus and my knee was bloodied and throbbing, and with that buggy shaking every time the wheels went over the logs, crikey, what a journey. I was wishing I was dead.”

The logs were unmilled, felled trees that lined the road through necessity. At that time of the year, the Wyczegda (Vychega) river that ran past Charitonowo into the Dwina, carried huge rafts of logs cut by the inmates of several forced-labour facilities up-stream. The logs in the already swollen river added to the wash that seeped into the surrounding marshland.

_______________

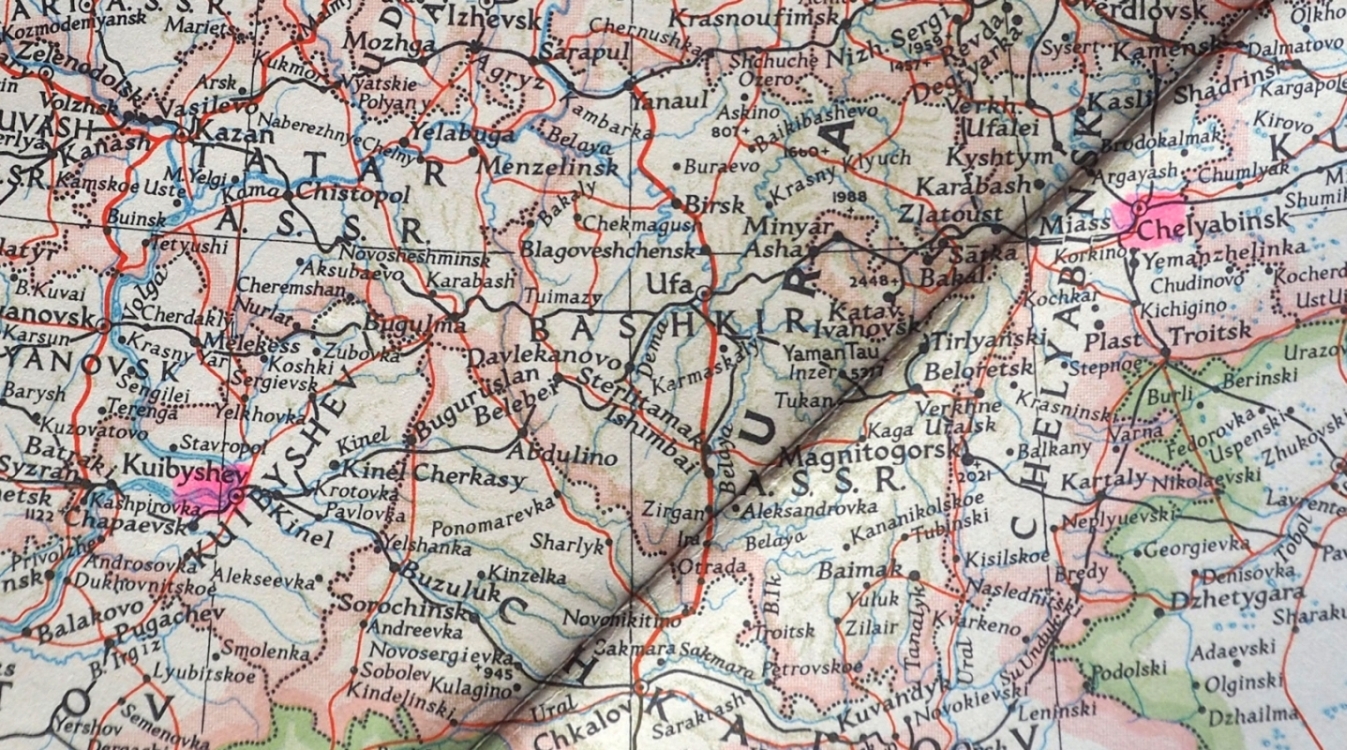

Exactly when the Kaźmieróws arrived in Kuibyshev (at the extreme lower right in the previous map) remains a blur to the still recovering Jan as the family travelled south for several weeks, mainly by train. Once there, Franciszek, Władysław and Piotr enlisted with the Polish army and received instructions to travel to Uzbekistan via Chelyabinsk.

The Soviets set up the first Polish military training camp in 1941, in Buzuluk, southern Russia, 170 kilometres on the south-southeast of Kuibyshev. Chelyabinsk is nearly 900 kilometres away from Kuibyshev to the east-northeast.

Instead of heading toards Buzuluk, on the railway line heading south-east of Kuibyshev, Franciszek Kaźmierów received instructions to head towards Chalyabinsk, on the main Trans-Siberian line.

The first Polish enlistees assembled in Buzuluk, but General Władysław Anders, Commander-in-Chief of the Polish forces in the USSR, wanted to move them south, towards better climatic conditions and freedom outside the USSR.

Despite the so-called amnesty for the Poles and the Sikorski-Maisky agreement, General Anders soon realised that, “Soviet authorities were still insincere with their dealings with the Polish army,”13 and that Stalin expected to use Polish men to help fight the Germans threatening Moscow.

The national geographic 1949 map of the Soviet Union that Jan used to follow his family’s journey shows railway lines in this area running predominantly in east-west directions. Only one ran through the vast Kazakhstan north of Uzbekistan, and that one did not link with Kuibyshev.

Did the Polish military authorities lead the Kaźmieróws to Chelyabinsk because they arrived before the Buzuluk military camp had been set up? Or was it because the group consisted of an adult man with children of various ages? Or was it because by the time they arrived, the Buzuluk camp had already disbanded?

General Anders soon knew that Buzuluk was unsuitable: it was isolated from the rest of the Allies, and suffered extremes of climate. By the winter of 1941, many men froze in their tents in temperatures of minus 52 degrees.14 The Soviet authorities allowed them to leave in early 1942, and establish new headquarters in Yangi Yul (New Road), near Tashkent.

Jan’s vivid memory of the train trip to across southern Russia to Chelyabinsk suggests that the inmates of remote Charitonowo in northern Russia discovered the news of the so-called amnesty and Polish army late, and missed the deliberate blocks the Soviets created. General Anders on the Polish men arriving in Kuibyshev:

Those who—sick, exhausted and in rags—arrived to join the army from the distant provinces of the boundless Soviet Empire were in a dreadful plight, but their transports were not allowed to remain by the Russians, who sent them on further south on the pretext that they would there await the arrival of the troops. But their journey did not end in the south. They were sent by rail to Turkestan, and from there by boat along the Amu-Daria for forced labour. Only a few of the many thousand men ever returned alive.15

Jan: “I distinctly remember going through the Ural mountains. There wasn’t enough room for all these people on the train and we jumped on a sort of a flat deck, the last ‘carriage’—like those used to carry heavy vehicles. The train was mighty long. I haven’t seen a train that long in my life, three engines, two in the front, and one in the centre of the train.

“We sat there enjoying the fresh air, as it chuggled along slowly through the mountains. It was a beautiful day, sunny and warm, and just as we were going through a pass in the mountains, we saw a gang of about four workers with spades beside the track. My father and two older brothers shouted out. ‘Are any of you Poles?’ One guy said, ‘Yes, I am a Pole.’ My father said, ‘Jump on the train. We’ve got amnesty, you’ve got amnesty.’ And no sooner had that guy heard it, he threw the shovel away, ran up, and jumped on with us.

“We happened to be on the main Trans-Siberian line. We got to Chelyabinsk, the most modern railway station that I have ever seen. I wanted to go to the toilet, so my father took me. It was like a five-star tourist hotel, marble floors, marble walls, urinals, water closets. I hadn’t seen a water closet before. I couldn’t believe my eyes, because it was all so clean, all so beautiful.

“I found out later that Stalin made sure that the passenger trains from Moscow to Vladivostok only stopped at places that had such out-of-this-world facilities. They did it to impress the foreigners.

“ When you came to a station, you still had to ask permission from whoever sat behind the desk—no matter what.”

“My father found out that other trains would take us to Uzbekistan, but we had to get off the main line, and travel south.”

Jan has not been able to confirm the family’s exact journey at this stage, except that he remembered Kurgan, even farther east. Two rail lines south left the Trans-Siberian from Petropavlovsk and Omsk, and some Poles told Jan that they went as far east as Novosibirsk. The Poles knew they were out of Russia when the railway tracks changed to narrow gauge.

“I don’t know how long we travelled on that narrow gauge. The trains were so slow, and would stop at almost any tinpot station to pick people up. It took us weeks.

“At that time, the NKVD had all the control of travel, but even if you got permission to travel,16 it didn’t mean you could get connections to travel such long distances. When you came to a station, you still had to ask permission from whoever sat behind the desk—no matter what. And, of course, all the lines were busy with the military traffic.

“It was easier for us, because my father could communicate in Russian and read Cyrillic, so he could navigate, and it helped that we travelled in a group, most of us from Charitonowo. We had to pay for the train tickets, but a lot of people didn’t have money, so they pooled their resources to get all the tickets.

“We travelled on the train as far as Tashkent [Uzbekistan]. When my father and my brothers went to register at the Polish military mission, the consulate instructed us to go to Katta Kurgan, and wait in a [Soviet] government kolkhoz until they were called up.

“A lot of people trying to get through to Tashkent couldn’t get into contact with the Polish army authorities at all, and if you couldn’t get through to the Polish army authorities, you were lost. More people died travelling to the Polish army than died in the [forced-labour facilities].”

A camel caravan took the Kaźmieróws on the last part of the journey to Katta Kurgan, then off the train-track north of Samarkand. Jan and his father rode together, Władysław rode with Kasia, and Piotr with Tomasz.

“That’s the way the communists worked. They had the ploughs, but no one could use them until some other factory delivered the attachments.”

“We might have been a dozen families by then. We had to work to survive. The glory box was long gone but luckily, my father kept his tools, because once they found out he was a blacksmith—and had the gear—the Russians put him into the blacksmith’s shop. They didn’t have a qualified man to do that. We stayed there maybe six or seven months.

“I think we arrived when the harvesting was over, because they were ploughing the fields. We passed two steel ploughs, still brand new, with green paint, and those Uzbeks were ploughing with wooden implements. I asked my father, ‘What’s wrong with those people? They are so primitive.’

“When my father got the job of blacksmith, he asked the people why they weren’t using those beautiful ploughs. They said they had no way to hitch them to the animals. That’s the way the communists worked. They had the ploughs, but no one could use them until some other factory delivered the attachments.

“My father said, ‘Find me some metal, I’ll make something for you.’ A couple of those Uzbeks disappeared on two camels, and they must have been away for two days. They arrived back early in the morning—I will never forget it—two camels side by side and this piece of railway line attached between them.

“My father almost had a heart attack. ‘Get this thing out of here! I don’t want anything to do with it!’ So they went away and buried it somewhere, but sure enough, the next day, NKVD soldiers arrived, looking for the saboteurs of the railway line. Luckily for the Uzbeks, nothing was reported to the authorities.”

_______________

“When we arrived at that place, my brothers and the other boys had a look around and saw these little pyramids in a paddock, about a metre high. Inside, they were full of potatoes, the Uzbek’s winter supply.

“We were about four families in a big mud house, and suddenly some Uzbeks arrived with some Kirkis with big knives. They wanted the thieves and they suspected the newcomers. My father and the others came to the conclusion that they had to pay, but the people didn’t want any of the Russian money. Some of our people had Polish coins, złoty, which had silver inside, and they were quite happy with that.

“It showed us how friendly the Uzbeki people were. They hated Russia. We hated Russia. So, we managed to lived together in harmony.

“My older brothers worked in the fields. My brother Tom was still looking after my baby sister. When she got really sick with pneumonia, he took her to the hospital in Mitan—a typical Russian hospital, nothing there. He stayed with her until she died.

“Next door to the blacksmith’s shop, there was a big pig, and it was my father’s job to look after the pig. One day, my father looked at the pig, and said we should make sausages out of it. I thought he was joking, but he told me to find an empty bottle, so I went scrounging around the cafeteria where the Russian soldiers used to have their meals.

“I found an empty bottle of vodka, and I grabbed it. What was he going to do with it? He took a hammer, broke the bottle in very small pieces and threw it in the pig’s trough. After a while, it was making terrible noises. My father said, ‘You’d better get the commanding officer. Tell him the pig is sick.’

“I went to the bureau, and told that commanding officer [in Russian] that the pig is sick. He came up, and oh, that pig’s screams were terrible. My father said, ‘Look, let us kill it and eat it, otherwise the pig will die and it will be no good for anything, or to anyone.’ The officer said, ‘It’s against regulations.’ It was supposed to go to the Russian soldiers.

“My father said, ‘Okay, we’ll let it die,’ but suddenly the officer said, ‘Kill it.’ No sooner had my father heard that, he grabbed that pig by its front legs, turned it over, and killed it with a sort of stiletto knife. He made hams from the two hind legs. The Russians took those, and they left the rest of the pig to the Poles, because most of the other people were Muslims. Our job, me and my brother Tom, was delivering meat to the other Polish families.

“My father had emptied the trough straight away. He took everything out and buried it somewhere. I’ll never forget that pig—or my pet donkey.

“I made friends with a donkey. I used to give him water to drink every morning, get him some scraps to eat, and we were friends. He would wait for me. One evening my oldest brother came back from work, and said to me, ‘Why don’t you show us your pet donkey?’ I thought, ‘Gee whizz, they’re interested in my donkey,’ and I brought the donkey along to meet them.

“No sooner had the donkey got his head through the door, my oldest brother hit him hard on the forehead with the back of an axe. The poor donkey, he collapsed right next to me, and they butchered him in front of me.

“There was no way of preserving meat there, but we had a good feed, and shared it with the other Poles. My brother burnt the bits we couldn’t eat, and threw the ashes outside, where the donkey slept, in case the guard came sniffing round. In the Soviet Union, everything belonged to the government.

“They were still looking for that donkey when two Russian soldiers arrived with a cart to take us to Turkestan, to the orphanage. One soldier turned to the other one and said, ‘What’s the smell?’ The other one said, ‘Donkey.’ They could have taken us to the authorities, but they just laughed.

“I remember the name Turkestan, quite a big town where the Polish army had formed an orphanage. My father became ill—I think it was TB, because he was coughing a lot—and he couldn’t look after all of us, so he arranged for us to go there, Peter, Tom and me. Peter was supposed to look after us.

“It was a big orphanage. There must have been about 400 kids. Food was a hunk of bread for breakfast, with some drink; lunch was something similar, maybe couple of potatoes. When my father came to visit us, he said, ‘What about the food?’ I told him we were perpetually hungry. He said, ‘What? The Polish government [-in-exile] had supplies sent over.’

“He went to see some Polish official, and they went to a storehouse, a magazine full of American aid, food and other supplies. The Polish authorities were expecting so many people—they kept arriving—that they were rationing their supplies, trying to save for the new arrivals. They had to look after so many kids, and they were trying to parcel out just enough for us to survive.

“I read reports later from General Anders that he refused to let his Polish troops go to fight on the [Russian] front because they were not yet fully trained, still not fully recovered, and because of that, the Russian authorities cut army rations. Yet the Polish army still had to share their rations with the civil population around them. They were in a predicament but my father, when he saw that store full of American aid, he was dumbfounded that we were hungry—virtually worse off than when we were in the kolkhoz, because there, we used to scrounge around; we could go into a paddock and find, or steal, something to eat.

“But in the orphanage compound you were locked up—everything’s locked up—like in a jail. You were afraid. If you went on the streets on your own, you got assaulted, maybe killed. When they took us to town, say, for a good wash, we used to go in a group. We had nothing to steal, but those Russian delinquents, in gangs and with knives, still tried to take something from us. They were mostly kids, but some were as old as my second oldest brother, who was 14.

“One day, a huge man appeared—he looked a bit like a Tatar—and suddenly those hooligans left us. We tried to communicate with him, and found out that he was a bandit.

“He was friendly to us. We felt safe when he was around. If we had to go to the town for anything, and he was there, we knew we would be okay. And he used to come to the orphanage.

“He had a big hunting knife, in Russian they called it a Finka, and a sharpening stone. He would sharpen his knife, and test it on his arm. If the blade cut the skin, he said, ‘That’s good. Tonight, I’m going on an expedition.’”

The last part of Jan, Tomasz and Piotr Kaźmierów’s journey out of the USSR in 1942 took them across the Caspian Sea. Jan has marked Tashkent and Katta Kurgan at the top right, Krasnovodsk and Pahlevi on the Caspian, and Teheran, Isfahan, Ahwa, Khorramshahr and Abadan. The last three were the cities and ports the Polish children and their caregivers travelled through on their way out of Iran in 1944.

Franciszek lost touch with his sons after the orphanage transferred them to Krasnovodsk, the main port in then Turkmen SSR, on the Caspian Sea. As far as Piotr, Tomasz and Jan knew, their father and Władysław, then 19, were with the Polish army. Jan remembers travelling by train and being ushered, with the other children, into the hold of a coal carrier. Jan had no interest in its name, but saw Cyrillic writing on its bow.

“It was like a big sardine tin. The army was on the deck, the rest of us below. The day was stinking hot, and the deck was iron. The hold was maybe 40 feet wide, with different compartments. There was so much coal dust, and with the heat, the kids were fainting. They were taken up on the deck, someone poured water on them, and brought them back. It was a most uncomfortable journey.

“We travelled through the day and night. I know it rained during the night, because my brother Tom somehow or other got on the deck, and couldn’t hide himself from the rain. I think it was 11 o’clock when we got into Pahlevi. I couldn’t wait to get off that dump of a bloody thing. By the time we got on deck, we were filthy, billowing black soot.

“The ship was that big, it couldn’t get into the wharf. We had to jump on a small Persian boat that took us to shore. Once we got there, there was a military mission directing people to go to different places.”

Although not ill, Jan and his brothers were—like all the Polish civilians escaping the USSR—malnourished, and joined the others in what the Pahlevi authorities then referred to as the “Dirty Camp” while they waited for clearance from quarantine and transfer to Teheran. Jan remembers living on a beach in blistering weather, close to water they had instructions not to venture into, because of its extreme saltiness and the shortage of fresh water to wash off salt that caked on skin. After an incident a few days earlier, Jan, and the boys with him, already treated the Caspian with suspicion.

“When we were waiting back in Krasnovodsk, one of the Polish women in charge said, ‘All right boys, because it’s so hot, why don’t you jump in the water and wash yourselves?’ I went. The water was so full of bloody oil, I just stood in the sand. But then, I felt it dragging me into deeper water. It was my first time ever in the sea, not only mine, others as well, and I couldn’t understand: the sand was parting, the water was gone, and still it was dragging me.

“Suddenly there’s an older kid, about 16, who grabbed me by the scruff of my neck, and pulled me out. It’s like the tide in Muriwai17 when it’s going out.”

_______________

“There was a Polish army headquarters in Teheran, and a big civilian camp. They were trying to get people out of the place, because there were too many there. I was called to the office, and the woman said:

‘You’re assigned to go to (somewhere like) Tanganyika or Uganda.’

‘Where’s that?’

‘In Africa,’ she said.

‘What about my brother?’

‘You’ve got a brother here?’ she said.

‘Yes, I’ve got two brothers here. I’ve got one brother with me, and another one who joined the cadets.’

‘You were supposed to go to Africa. You go to the office now and join the cadets,’ she said, not the senior cadets—the junaki—but the junior cadets, the Orlęta.

“So I went to the office, and I said I wanted to join the Orlęta because my brother was going to go to Isfahan. Luckily, they accepted me.”

Tom and Jan moved to Isfahan, to Number One Hostel, and Peter left for Iraq with the junaki, the military cadet arm of the Second Polish Corps, set up specifically to house and school teenaged Polish boys at first, but which later took in teenaged girls.

Boys and staff at Number One Hostel, Isfahan. Jan is immediately in front of the woman in black on the right, and Tomasz is in the second sitting row, smiling in front of the boy immediately to the left of Jan. Dr Janina Budzyna-Davidowska, the dentist who accompanied the children to Pahiatua, is to the far left, wearing the striped dress. Jan also remembered the “lovely” nursing sister in white, to the right of Dr Budzyna-Davidowska, who looked after him when he contracted malaria shortly before leaving for New Zealand in 1944.

“I think it was the Shah’s cousin who owned that place, and he lent it to the Polish authorities. School started. There were no classrooms. It was so hot, the tables were outside, under the trees. When winter came, we were inside.

“We started to get some decent meat tucker. They made rissoles and kotlety [chops]. Of course, it wasn’t plenty. You eat it, you run around for 10 minutes, and you’re still hungry, but, there were three meals a day.

“In summertime, we used to have a siesta because of the heat—it was about 40 degrees—and they used to buy pomegranates in season. We got a pomegranate each, de-licious, and sometimes grapes, beautiful grapes, greenish-yellow, oval in shape, and oh, so sweet. And they had something they called harbuzy, melons shaped like rugby balls—most delicious. The fruit in Iran is fantastic, especially pomegranates, because of the sun.

Polish boys in Isfahan with Św. Mikołaj (St Nicholas). Jan’s bed faced the third window from right. “One morning, I woke with my bed on the other side of the room. The 30 beds were all over the place. There had been an earthquake and we had slept through it. The carer came in with her hands clasped, ‘Thank the Lord you are all safe.’ The building survived, only the mudbrick walls surrounding it fell down, but the villages higher up were not as lucky.18 All the boys had the job to fix the mudbricks. The property must have been about 10 acres. The building was reinforced concrete, but the whole property was surrounded by the mudbrick wall, about 18 inches thick, and about eight feet high.“

_______________

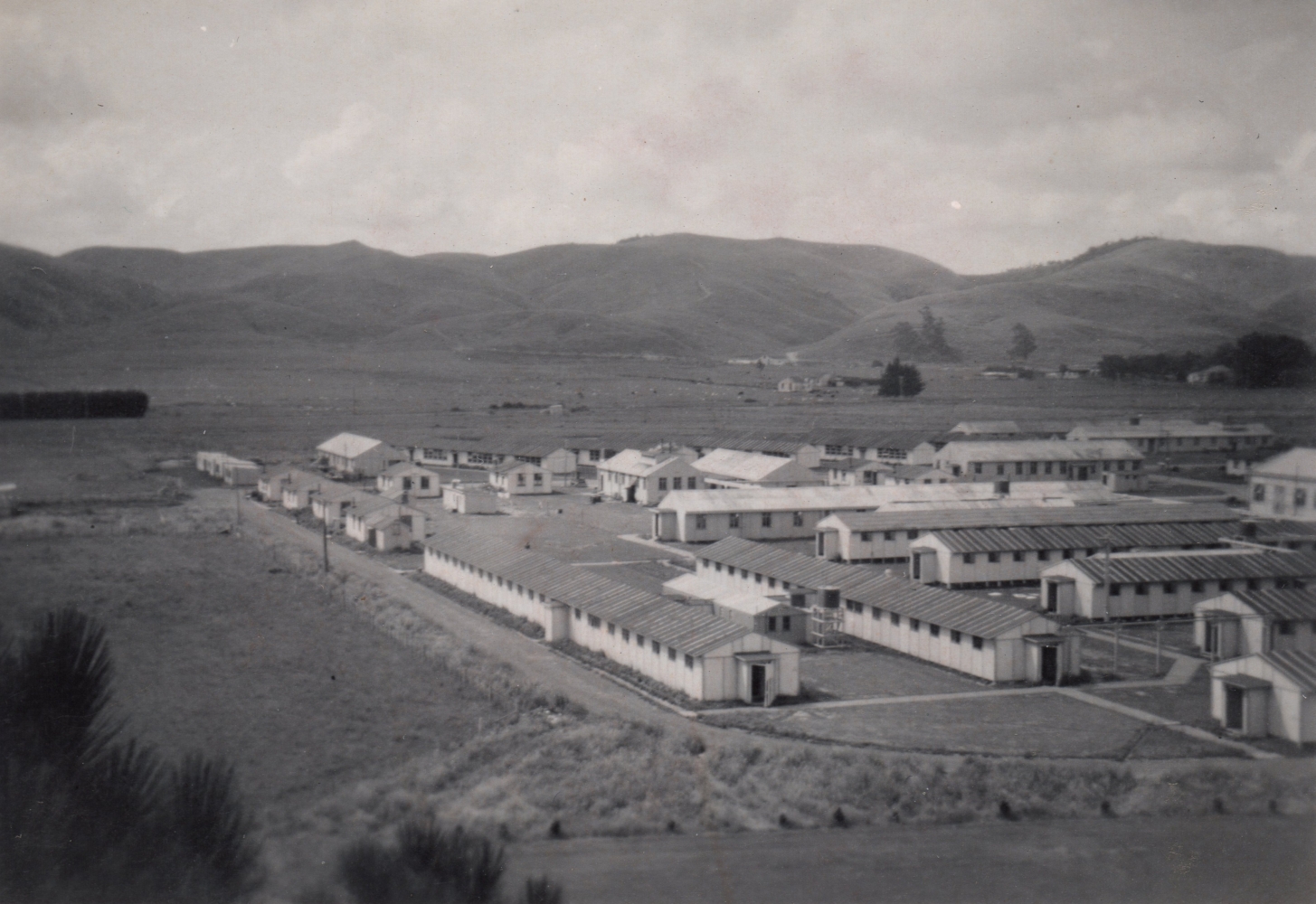

Jan and Tomasz arrived in New Zealand on 1 November 1944, among the 733 Polish children and their 105 caregivers invited by the New Zealand government to spend the rest of the war in a safe haven.

Prime Minister Peter Fraser and his wife, Janet, took a personal interest in the Polish children, who became—and still are—known as the Pahiatua children, thanks to their camp in the central Manuwatu town. After the Allies officially handed eastern Poland to Stalin in 1945, and the rest of Poland became communist-controlled, Mr Fraser extended that invitation to all the Pahiatua Poles who wished to remain. Some returned to Poland, and the Red Cross helped connect others with families they had not seen since Uzbekistan, Pahlevi or Teheran.

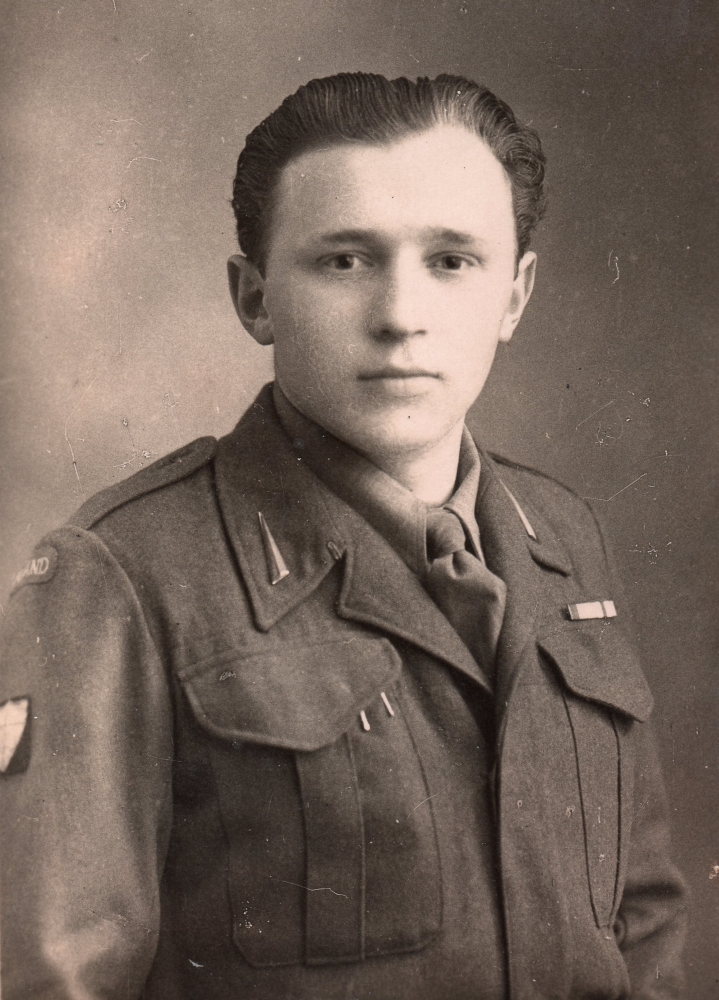

Piotr Kaźmierów fought with Anders’ Second Polish Corps throughout the Italian campaign, including at Monte Cassino.

Piotr sent Jan this photograph from San Sewerino, Italy, taken on 15 April 1946.

“I didn’t write to him often [from Isfahan] and he complained. I said I had to tear out a page from my book to write, and that I didn’t have the money for the postage. He sent me ₤8 to share with my brother.

“I was sent to the office in Establishment 1 [Number One Hostel] and there was the registered mail for me from Peter. The lady in the office took us to a bazaar. We went by doroszka, wagons for passengers. It was beautiful there, all colours and gold everywhere.

“She advised us to buy suitcases first. What were we going to do with suitcases? But we did. Then we got some German-made ink, a dipping pen, and a lot of paper. Then she said, ‘What are you going to buy for your brother?’ We looked around and found this solid silver cigarette holder. It was beautiful, carved, so we got it and sent it, registered mail, to my brother.

“Years later, I asked him about that cigarette case. He said he had stopped smoking and had given it to a mate.

“I got a visa for him to come to New Zealand but he had already decided that he would join his mates in Canada. We hadn’t stayed in good contact, so he stuck with his mates.”

Piotr is second from right. He did not date this photograph, but addressed it to his beloved brother Jan, from sunny Italy.

_______________

The brothers had heard nothing from their father or Władysław since Franciszek last visited them in the Turkmen SSR orphanage in probably July, maybe August 1942. They assumed both had died, particularly as Franciszek was ill when he had left them.

But in 1946, Franciszek wrote to Jan in Pahiatua. He had found his sons through the Red Cross. He told them that he and Władysław did not get out of the USSR with the Polish army in 1942.

Franciszek’s health had deteriorated in Katta Kurgan, and when their call-up to the Polish army finally arrived, Władysław stayed behind to nurse his father. By the time they arrived in Krasnovodsk, Stalin had closed the border. Like thousands of other Polish men of military age, the Soviet authorities gave them two options: join the Red Army, or go back to the NKVD forced-labour facilities.

Both joined the Polish First Kosciuszko Infantry Division, under Soviet authority and commanded by the Polish deserter Colonel Zygmunt Berling. Berling had started organising the stranded Polish men into his own units as soon as the legitimate Polish army had completed the second mass evacuation of Poles from the USSR in early September 1942.

Father and son separated. Franciszek served in one of the division’s transport units and Władysław was made a lance sergeant.

“They both fought at the Russian-German front, in Lenino. The Poles weren’t properly trained, didn’t have the proper equipment, were not physically fit, and the Red Army put them in front of the Germans in a boggy field in Byelorus.”

Although Franciszek died believing that Władysław died in the Battle of Berlin, the last major battle in Europe in 1945, he did not survive the Poles’ first battle on Russian soil.19 For the Poles forced to fight for their former captors, the Battle of Lenino on 12 and 13 October 1943 was a disaster. More than 500 Polish soldiers died.20 Władysław’s name appears with the others on one of the common graves at a museum in Lenino that commemorates the battle.

Franciszek and his two younger brothers, Gregorz and Antoni, returned to post-war communist-controlled Poland. The three brothers did not reunite, principally because Gregorz, who served with the Anders’ Army, joined the communist-controlled Polish government’s militia, the UB (Urząd Bezpieczeństwa, the Department of Security). Gregorz later changed his name back to Rozdolski.

Jan received about six letters from Franciszek before he died in 1947. After Jan described his life in New Zealand, his father recommended that he stay rather than return to an uncertain future in Poland.

Despite the lack of a parental tie, Jan appreciated his Pahiatua ‘family,’ and the freedom that the children’s camp gave him. He again felt safe.

He did what all boys are supposed to do—explore their surroundings and get into mischief. With their personal memories of guns, it became inevitable that one of their favourite pastimes was to create explosions.

Jan is on the far right in the first row behind the teachers.

“On one of our expeditions from the camp—four of us—we came across two guys chopping trees, and we watched them. Some of the stumps were that big, they were boring into them with an auger, and they had a contraption, a hard, metal cylinder, that they filled with black pellets. They blocked it with paper, put a fuse in a little hole, rammed it into the auger hole, lit the fuse, and split the trunk so they could get it out of the ground.

“We thought, ‘That looks like great fun,’ so we said, ‘We’ll do that for you.’ They liked that. We finished, and one of the boys said could he have some of the granules of powder? The guy said, ‘Yes, help yourself,’ so he took a handful.

“We thought he was going to make some kind of gun, but then there was a problem: a farmer complained that there was an explosion and some of his bank collapsed into the river. That boy had put the granules into a bottle and tried to stun the trout in the river—that river had some big, brown trout.

“The farmer complained to cops. The cops complained to Major Finny, who was the big chief of the camp, and Finny complained to the caregivers. So eventually Mr Białostocki—he had just come out from the Polish army—called us one by one. He knew roughly how many boys were out, and he heard the story. Apparently, those guys made out that we’d stolen the gunpowder, but our stories coincided, so they believed us.”

Tomasz Kaźmierów in New Lynn, Auckland, on a bike that he received from the family he boarded with, the Cuthberts. The bike had belonged to their son, Jim. When Tomasz upgraded to a better bike six months after Jan arrived in Auckland in 1948, he gave it to Jan.

“Tomasz went to high school at St Pat’s [St Patrick’s College] in Wellington in 1946, or ’47, but the teachers gave up on them. It was too difficult to teach them English and they were assigned to go to work. He went to Auckland, to live with the Cuthberts, and Mr Cuthbert, who was a boilermaker, got him an apprenticeship as a boilermaker. People who offered to take in the boys had an influence in where they went. [The Catholic church in New Zealand asked parishioners to foster Polish children.]

“He couldn’t stand the smell. He had a problem with his nose—a horse had kicked him in Poland—and he didn’t finish. He worked on a farm in Waikato, but he had an accident on his motorbike when he came up to Auckland to visit. When he came out of hospital, he did odd jobs in factories, and as a gardener at a Catholic girls’ school.”

Tomasz gave Jan his Brownie camera when he left Pahiatua. Jan took several photographs of the camp, climbing some of the tall macrocarpas for better views.

The chimneys in the middle background here were the source of the central heating system that travelled through the raised pipes seen between the buildings. The empty length of land between the buildings on the right and left is the old racecourse, which made way for a wartime internment camp for “aliens” before the New Zealand authorities moved the “aliens” to Soames Island and refashioned it into the children's camp.

The teachers’ quarters at the Pahiatua children’s camp.

On the left hand side is the hall, and on the right, the girls’ quarters. The heating pipes running between the buildings are in the background.

Jan’s Brownie camera did all the advertisers said it would—create a snapshot. A modern camera may have enticed him to zoom in on the buildings, but from one of trees, Jan’s shot of the camp included the old Pahiatua racetrack in the foreground. The girls’ dormitories are the closest buildings and the hall and dining rooms run perpendicular.

Taken soon after the one above, this shot towards the east, shows some of the foothills towards Kaitawa, and between them and the camp, the proximity of several farmhouses.

The Pahiatua camp’s main street, leading to the classrooms on the right.

The boys dormitories, with their bathrooms in the foreground on the right.

Jan’s carefree days in Pahiatua ended with the national polio epidemic, when schools opened on 1 March 1948. He joined Tom in Auckland and went to St Peter’s College in Epsom, Auckland. The difficulty of the English language hit him hard.

“In Pahiatua, we had English lessons for an hour a day, but it wasn’t enough. With Polish, the spelling is how you say it, but the English words were spelt so differently, it was impossible to work out.

“They assigned each of us with a buddy to help us during classes. I was there three years, but I always had a problem with the spelling.

“In high school, I got work in the wool stores, Dalgety’s. We classed the wool and put it into bags. I worked the Christmas break, and in the evenings to 8.30. By the time I left high school, I had saved ₤75.

“I started my apprenticeship at Fletchers Construction and got my first wage, ₤1 7s 6d. But my board was 30 shillings [₤1 10s], so I had to use my savings to pay my board.

“The Catholic Social Services [were one of those who] informed the authorities about the situation regarding the conditions [for boarders]. The week after, I got given a government subsidy of 10s a week for board allowances. It was for any New Zealand child boarding, because in those times, you could start work at 14, but the wage was peanuts unless you could get work at the wharf. Tom used to work as a ‘seagull’ at Auckland wharf. You’d go there, and if they picked you to work for the day, they paid well, but the work was scarce, unless you had connections.”

_______________

Jan met Australian Dorothea Ivey at the Crystal Palace Dance Hall in Mt Eden, while she visited New Zealand on holiday. They married in 1965 and had four sons, Peter, Francis, Michael and Bronisław, within four and a half years.

Jan’s wartime experiences lead him to the kind of life in New Zealand that would have been impossible in post-war Poland. While there is no doubt that the harrowing realities for Poles in the USSR were traumatic, his father and older brothers instilled in him a pragmatic outlook on life, and his time at the Pahiatua camp continued the positive influence.

“I parted company from my father when I was eight. I acquired knowledge from schools, and at the Polish camp at Pahiatua, there was a military discipline. There was no such thing as not doing something because you didn’t want to. You were assigned to do a certain job, and you had to do it.

“Our cafeteria had something close to 300 boys. For each breakfast, lunch and tea, there might be 600 plates to be washed. The [New Zealand] army used to have a dishwasher, but when the army left the kitchens to be run by the Polish women, they used to cook the meals, and so many boys per week had to clean the place. Those boys had to be there after breakfast, after lunch, after tea. That was their job, and after one week, there would be another group. That’s the way it was. You couldn’t whine your way out by saying you were a bit sick, or some other excuse. You had to do it.”

Dorothea: “Only in very recent years have they even begun talking about it between themselves. For the first 20 years, we’d get together with the other Poles, and their past wouldn’t come up in conversation. It was only as they got older that they started reminiscing.”

Jan: “We didn’t talk about our lives much. My mates from the camp, I hardly knew their background. We were just not interested then. People who used to talk about what happened to them used to annoy us, because we thought they were trying to get sympathy from us: I’ve been there as well and I’m not asking for your sympathy.”

Jan underplays his accumulation of knowledge, but the Polish and English histories and bibliographies that fill the Kaźmierów home reflect many years spent digging into the various nuances of his Polish background.

He may not have appreciated others’ stories as a schoolboy, and his own never wallow in self-pity. He lost his pet donkey, but to whom could he have cried? By seven, he had learnt the true value of a life.

© Barbara Scrivens, 2020

APART FROM THE FIRST, ALL PHOTOGRAPHS COME FROM THE KAŹMIERÓW COLLECTION.

THANKS TO THE NORTH AUCKLAND RESEARCH CENTRE IN THE TAKAPUNA LIBRARY FOR THE LOAN OF AUDIO RECORDING EQUIPMENT.

ENDNOTES:

- 1 - Order no 001223, dated 11 October 1939 and signed by General Serov.

- 2 - Kwestionariusz from Stanisław Nieścior, who was in the neighbouring Tiesowaja facility.

- 3 - This spelling from the Strony o Wołyńiu. Jan has been told of various other spellings, including

Bolygów.

http://wolyn.freehost.pl/ - 4 - Map from Mapywig, an institution that has collected and archived maps from the Military Geographic

Institute in Poland 1939-1939. The English version of the site is:

http://english.mapywig.org/news.php

The map index is superimposed on:

http://igrek.amzp.pl/mapindex.php?cat=WIG100 - 5 - After the Soviets invaded Poland, they dismantled most of the factories, including an almost built radio

station, and sent them to the USSR. They also deported 10,000 of the city's Polish inhabitants in cattle trucks to

Kazakhstan. It is not clear whether the 1,550 they arrested were soldiers of the aforementioned 13th Kresowy Light Artillery

Regiment and the Łuck National Defence (Poland) Battalion, or where exactly they were sent.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lutsk - 6 - Reported by Pravda on 18 September 1939. Information from the CIA, dated 23 January 1943,

declassified and approved for release in 2012.

https://www.cia.gov/library/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP08C01297R000500160034-5.pdf - 7 - Jan uses the terms Bolsheviks, Soviets and Russians to mean the same people.

- 8 - For a comprehensive account of the 1919–1920 Polish-Soviet War, read Norman Davies’ White Eagle, Red Star; The Polish-Soviet War 1919–1920, first published in 1972 by Macdonald & Co.

- 9 - Aleksander Gurjanow, List of Deportee Transports via Rail 1940-1941, By Arrival Station, Karta 12, 1994, Warsaw.

- 10 - I put ‘deportation’ in single punctuation marks to show the irony of the still widespread use of the word regarding the Poles who the Soviets forced out of their homes in eastern Poland. Deportation is linked to an action involving. The Poles were not foreigners. They were living in their own country.

- 11 - Information from the Indeks Represjonowanych,

https://indeksrepresjonowanych.pl/int/wyszukiwanie/94,Wyszukiwanie.html

If anyone would like help looking in the index for their families, please contact us through the Home page. - 12 - I collated the information on the Wołyń list with the Indeks Represjonowanych.

- 13 - Anders, Władisław, An Army in Exile: The Story of the Second Polish Corps, originally published in 1949, reprinted in by Battery Press, Tennessee, ISBN: 0-89839-043-5, page 94.

- 14 - Ibid.

- 15 - Ibid.

- 16 - After the ‘amnesty,’ the NKVD commandants issued special travel documents to the Poles.

- 17 - New Zealand beach, on the west coast of Auckland.

- 18 - A magnitude 4.8 earthquake, at a depth of seven kilometres, struck Iran’s Golestan province on 5 April 1944. At least twenty died.

- 19 - Peter found out the truth of Władysław’s death during a trip to Poland in 1958.

- 20 - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Lenino

If you would like to comment on this, or any other story, please email editor@polishhistorynewzealand.org.