Joanna Adamek Kalinowska

Joanna Adamek Kalinowska took the long road to New Zealand.

Three years after Britons held street parties on 8 May 1845 to mark the end of WW2 in Europe, Joanna—and about 19,000 other Polish mostly women and children—remained in limbo in Africa.

In New Zealand in 1944, the government gave shelter to 733 Polish children and their 105 caregivers, and invited them to stay for the duration of the war. That invitation was extended after post-war Poland became communist-controlled.

In contrast, the Poles in Africa heard British politicians urging them to return to ‘their’ country. They refused. They knew their so-called Allies had given their land and homes in eastern Poland to Stalin, the same person who had engineered their forced removal to the USSR in 1940 and 1941. Besides, those whose husbands, fathers, brothers and sisters had not died in the war, had yet to reunite.

From 1946, the Poles in New Zealand had been integrating with the English-speaking society. Some returned to Poland, but scores of husbands, parents, brothers and sisters joined their wives, children and siblings in New Zealand.

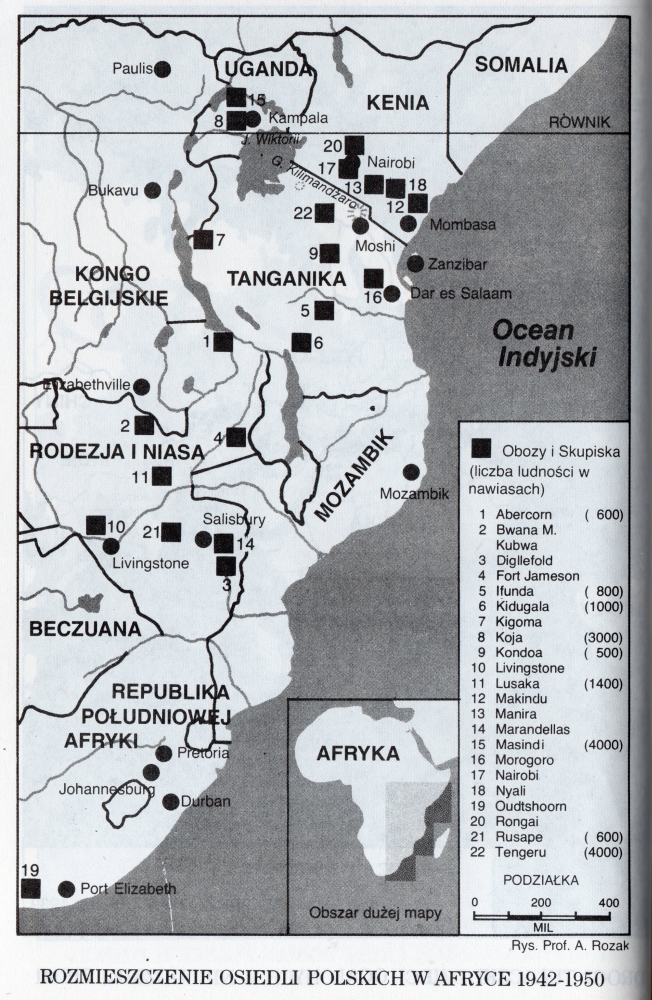

A similar Polish children’s camp in Oudshoorn, South Africa, also helped their young charges integrate, but the Poles farther north had nowhere to go. They continued to live in the 21 refugee camps scattered along eastern and southern Africa, within the hospitality and warmth of the African people and climate, while those British politicians finished arguing about their collective fate.

In 1946, ships carrying Polish troops who had been pivotal in the 1944 battle for Monte Cassino, arrived in the UK from Italy. In 1947, passenger ships carrying “displaced persons” from India and Lebanon sailed to Southampton and Liverpool. Polish mothers and children from the African camps only started leaving in 1948, and many saw their last African sunset in 1950.

Joanna, with her mother and younger brother, arrived in Southampton in May 1948. She lived in England for 12 years before moving with her sons to join her husband in South Africa. Thirteen years after that she finally got the chance to settle permanently—with two more children—in Auckland, New Zealand.

When I first met Pani Joanna in July 2018, I was struck by her forthright charm and keen memory and knew I would not forget her sincerity or sparkling eyes. I thank her for her kindness and her time.

—Basia Scrivens

LIKE IT WAS YESTERDAY

by Barbara Scrivens

Polish teenager Joanna Adamek watched a towering Ugandan baobab judder violently before her as she struggled to stay upright on the shaking earth under them both, and for a moment forgot why she was in Africa.

The baobab, which sheltered and shaded the back yard it shared with the Adameks and other Polish families on the outskirts of Masindi, may have experienced earthquakes before, but few as strong as the one that reached six on the Richter scale on 18 March 1945.1

For Joanna, two weeks away from her 17th birthday and a survivor of a Soviet forced-labour facility in northern Russia, the unexpected experience became all the more frightening because she had thought that she was safe again.

“The earthquake pushed me out of the hut to have a look at what was happening, and I noticed the shaking. That baobab stood in the middle of the yard, and I saw the ground shaking around it.

“I can remember like it was yesterday, the baobab and the ground shaking so vigorously under my feet. I was very scared and started to think, ‘Where can I go?’ But there is nowhere to go once the earthquake starts. You can’t run anywhere. Where are you going to run? You can’t hide.

“The house, if it had been brick, would have been shattered. It didn’t fall down because it was made of bamboo and clay.”

The previous five years had conditioned Joanna into such fight or flight thoughts. She knew all about being caught in a situation from which she could not escape: The Adameks were among an estimated 1,700,000 Poles incarcerated within the USSR after the Soviet army invaded Poland on 17 September 1939.

In war, one may expect a certain number of military casualties or prisoners-of-war, but Stalin’s secret police, the NKVD,2 rounded up anyone they considered “anti-Soviet elements,” including babies, children, pregnant women, and the elderly. The NKVD organised and oversaw four mass transports of around 900,000 civilians out of eastern Poland on trains previously used for cattle. In February, April and June 1940, they deposited the Poles in hundreds of forced-labour facilities and prisons throughout northern Russia and Siberia, mostly in taiga forests where they cut wood for the Soviet railways under a “labour for bread” system. In June 1941, they forcibly removed mostly wives and children of the Polish military and police to Kazakhstan, and left them to fend for themselves.3

June 1941 marked an abrupt change of fortune for Stalin: his former ally Hitler ordered an attack on Russia. As the Germans neared Moscow, Stalin’s representative in London, Ivan Maisky, entered into diplomatic talks with Polish Prime Minister and Commander-in-Chief General Władysław Sikorski. Sikorski negotiated a deal whereby the Poles in the USSR would be granted ‘amnesty,’4 would be allowed to leave the NKVD forced-labour facilities, and would form a Polish army in Russia. Stalin expected to use the Poles to help protect Moscow from the invading German army. General Sikorski, however, concentrated on getting his fellow citizens out of the USSR.

In April–May and August–September only about 115,000 Polish soldiers and civilians escaped the USSR.

Unaware of the politics behind Stalin’s gesture, the surviving Poles in the forced-labour facilities and prisons needed little encouraging. Once news of the ‘amnesty’ trickled through—from September 1941—they left the facilities, and faced journeys of thousands of kilometres as they headed towards the Polish army’s enlistment stations.

The Soviet authorities seemed surprised that the Polish fathers refused to leave without their families, but the Poles had already seen too many die under the facilities’ harsh conditions, and knew many more would not survive another Soviet winter.

General Władysław Anders, tasked with organising the new Polish army and getting the Poles out of the USSR, estimated that already half of them had died by 1942. In April–May and August–September only about 115,000 Polish soldiers and civilians escaped the USSR.

“We left behind hundreds of thousands, and our hearts were heavy,” General Anders said in his book, an army in exile, as he questioned the pitiful numbers of ragged Poles lucky enough to get to Persia.5 There, they came under the joint care of the British government and the Polish government-in-exile in London. Military personnel moved to training camps in the Middle East. Others went to civilian camps in Teheran and Isfahan and were eventually sent to refugee resettlement camps in safer parts of the world.

_______________

By 1943, Joanna, her mother, Franciszka, and her younger brother, Jan, had joined about 19,000 mainly women and children in 22 temporary Polish settlements in eastern and southern African countries still controlled by the British.

“We were told we were going to India. There was a refugee camp close to Karachi, which belonged to India in those days. We stayed only a few months because they said there wasn’t any more room for refugees, so they moved us to Africa.

“We went by ship to Mombasa and stayed in Kenya for a few months. I don’t know whether they intended to settle us there or whether they were working out where to put us. They took us for excursions on lorries. Most scary was when they told us about the vicious wild animals roaming around.”

The refugee authorities eventually assigned the Adameks to Masindi in Uganda. Army lorries took the Poles most of the way but the last part of the journey had to be made on the Nile river, where Joanna kept a watchful eye on the crocodiles slinking around their barque.

For five years, the Adameks lived in Masindi’s village number three, one of six or seven that housed about 4,000 Poles. Their village was comfortably enough away from the river for Joanna to relax about crocodiles but the roaring lions wandering the roads at night kept her vigilant.

Polish Refugee Camps in Africa 1942-1950. The placement of the camps is not necessarily accurate. Rusape, 21 on this map, was closer to no. 3.6

“I can’t remember the name of the supervisor of the camp but he and his wife were English and their decisions were final. It was the first time I saw a woman in trousers. I remember them walking along the road and she had three-quarter length trousers. They went for a walk quite often.

“I went to the grammar school. Kazimierz Arnold was director. He was, as we say in Polish, ‘jak piła,’ strict with everything. In those days, people in offices everywhere were strict. That’s how it was.

“One teacher, she taught us English, was the wife of someone who must have been in quite a high position in Poland because he could speak English and she could speak English. We called her ‘Horpina’ from the [Henryk] Sienkiewicz trilogi polski. She was horrible. She hit one girl in the face because she answered back, said something that offended her. You didn’t argue with the teacher. Horpina was a big woman, well-built. Her husband had an office at the camp and they were in contact with the British chief.”

Joanna, right, and a friend in Masini, circa 1944.

“I can’t remember Masindi the town but I do remember the settlement. We walked to school and I remember it was very, very hot. Walking home in the afternoons, we wore helmets because it was so hot, exhausting.

“For three months—the dry season—not a drop of rain comes. And they call it winter. The grass is all brown. Trees drop their leaves. They put a match to it, and it burns, and after that the new grass comes. It takes a while for new grass to come, and that’s when the spring starts.

“They have to burn the grass. How otherwise can they control it? It would grow and grow and grow.

“Father used to send money from the army. [The authorities in Masindi] gave us either ₤10 a week or a month, a little bit of pocket money and the rest, father sent.”

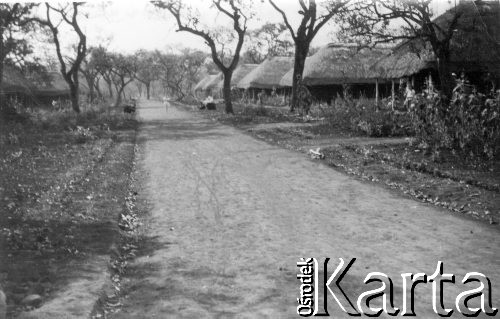

A street in one of the Masindi camps. This photograph was taken in 1945 and forms part of a collection donated to the KARTA centre in Warsaw.7 This is exactly as Joanna remembered the Masindi streets near where she lived; the residents called them “Ulica Rób Co Chcesz” (Do What You Want Street).

The Ugandans who now live in the houses built for the Poles have replaced the thatched rooves with more functional corrugated iron.8

Joanna knew her nights listening to the roar of lions would eventually end. Three years after the 1945 VE (Victory in Europe) Day, Poles in Africa talked about leaving. Throughout their stay, the Adameks received letters from Joanna’s father, with the Polish army in Italy, and her older brothers, Bronisław, with the air force in England, and Roman in Egypt with the junaki (the military school run by the Polish army).

With General Sikorski’s death in a suspicious air crash on 4 July 1943, Poland lost her best diplomatic weapon and Stalin cultivated the British and American Allied leaders to his advantage.

In Teheran in December 1943, the same city where scores of civilian Poles remained in tented camps and other temporary shelters, Roosevelt and Churchill bent to Stalin’s wishes and set in motion the means to give him the entire eastern Poland. Two more conferences in 1945, in Yalta and Potsdam, sealed Poland’s fate. By 1948, Soviet-led communists had entrenched themselves in post-war Poland and surviving Poles outside its borders knew the Poland they had left behind had changed dramatically—and for the worse.

In 1948, most of the Polish diaspora had lived in an eastern Poland that no longer existed.

_______________

Joanna Adamek Kalinowska was born on 1 April 1928 in Antoś, a kolonia (settlement) near Brody in then-eastern Poland. She felt her parents could have tweaked her birthday by a day so she could have avoided the embarrassment of sharing her special day with the one used to tease and make fun of people. She envied Jan, seven years younger, for arriving on 31 March.

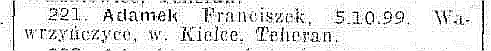

Her parents were both born in 1899. Franciszek moved east from Wawrzeńczyce, about 20 kilometres from central Kraków, after serving in the 1919–1920 Polish-Soviet War. Franciszka and her adoptive parents, Józef and Franciszka Dybczak, arrived in Antoś from Pewel Wielka, about 80 kilometres south-west of Kraków.9

Franciszek Adamek met Franciszka Dybczak while he was visiting his older brother, Jan, at his farm about two kilometres from where the Dybczaks lived. As volunteers in the war against the Bolsheviks, both brothers had been given the option by the new 1918 Polish government to take up land but, after meeting Joanna’s mother, her father surrendered his to be closer to her.

They married. Franciszek moved to the Dybczak farm and worked the land with his in-laws.

“People used every part of the animal. Well, they couldn’t sell it to anyone.”

“He did buy land in Antoś. The settlement was already full but somebody was selling. They worked the gospodarstwo [farm] together, 21 hectares.

“They grew everything, wheat, corn, potatoes, and they had a big garden, an orchard and a vegetable garden.

“I remember that vegetable garden because we used to steal peas and mak [poppy seed]. They grew the mak for baking. We shook the seeds into our palms and we ate them. It’s what children did in those days.

“Babcia used to cook for all of us. She was a good cook, and Mum baked.

“I remember the bigos and pierogi. Once or twice a week we had meat or chicken, and usually something from a pig that they killed. They salted the meat and made kiełbasa [cured, spiced garlic sausage] and salceson.

“The salceson was a mixture of meat and pig’s ears. They put it in the pig’s stomach and cooked it in a big pot. It was lovely. I can still see it.

“For the first few weeks after they killed the pig, we had kiszka. It was a sausage made of pig’s blood, heated, then had some kasza [buckwheat] added, and it was delicious. When I think about it now, I have the shivers, I wouldn’t eat it if you paid me, but then it was delicious. You had to know how to prepare it, and you couldn’t keep it longer than two or three weeks because there were no fridges in those days.

“Everything was kept in the komora, a special dark room for the preserves like the kiszona kapusta [sauerkraut], kiszone ogórki [gherkins] in beczkach [barrels], the preserved tomatoes, which weren’t many, and the kwaśne mleko [buttermilk]. In the piwnica [cellar], we kept potatoes and other vegetables, milk and cream and the salted meat, like the kiełbasa and salceson hanging from the roof beams.

“Oh, the doughnuts… The white ones were steamed with sugar on top.”

“People used every part of the animal. Well, they couldn’t sell it to anyone. The biggest town, Brody, was 25 kilometres away and in those days there were no buses or cars. People had horse-drawn carts.

“I saw a car in our settlement once or twice a year, some dignitaries from Brody. They didn’t come to our place. They were probably visiting the wójt, the mayor of the village. I remember only one, a Mr Pawlus.”

The Dybczak-Adamek farm carried several horses, cows, pigs, chickens and geese. They kept ducks for their feathers, used to make pierzyny (eiderdowns). The effort that went into making each pierzyna made them prized and appreciated bedcoverings. Each feather had to be broken and its tough inner stem removed so only the softest bits went into the fillings. Usually this was “women’s work” but Joanna’s father did not like to be idle in the evenings and helped.

Joanna’s mother excelled in baking and specialised in apple strudels, babka (enriched Easter fruit loaf), “all sorts of” biscuits, and steamed and fried doughnuts.

“Oh, the doughnuts… The white ones were steamed with sugar on top. Mum put the doughnuts on muslin in a pot of water and covered the top. The water boiled, the steam came in and cooked them. Delicious. The brown ones, she fried in pig’s fat, which is white and doesn’t go hard like cows’ fat, which is yellow.”

Everybody helped on the farm and in high season, the family employed extra labourers. Joanna and her brothers walked the few kilometres to school in the summer but in winter, when the snow often lay deep, Franciszek took his children in the sled.

Antoś was about two kilometres long, with houses on both sides of the road, occupied by Poles, Czechs, Ukrainians and a few German families.

“Villages nearby were mostly Czech and Ukrainian but ours was a big Polish village. We were the newcomers. Powiat Brody, poczta Leszniów, kolonia Antoś.”

_______________

“… two soldiers with guns… one was following us saying ‘Sobiraysya! Sobiraysya!’ [Get ready! Get ready!] and making us hurry. ”

Immediately after the Russians invaded Poland in 1939, Antoś residents expected some kind of retaliation as payback for the Polish victory in the 1919–1920 Polish-Soviet War. They were surprised and relieved when there seemed to be none.

“There was not much trust between the Russians and the Poles because of what had happened in the past, but they left us alone. There was no persecution or anything like that until the day they took us away. There were more persecutions in Antoś after we left, but they seemed to leave the other villages alone.

“I had a Ukrainian friend, older than me, at school and I have nothing bad to say about her, but after the Russians came, some of the Ukrainians took advantage of the Poles.

“I don’t remember much about that day, 10 February 1940. We got up as usual and then the Russians arrived, two soldiers with guns. It was still early. I can’t remember much but one was following us saying ‘Sobiraysya! Sobiraysya!’ [Get ready! Get ready!] and making us hurry.

“The other one stood as a guard outside the house. I don’t know if there were others.

“They gave us some time to pack because we took quite a bit. We took all the bedding and some clothes. Dad and grandfather managed to kill two pigs and quite a few chickens. I remember the meat because it was frozen and we could take it because it was winter. It was a good thing, because in the beginning in Russia we had food. A lot of people didn’t have food. They weren’t allowed to take anything. We were lucky in that respect. For quite a few months we had our own meat and we didn’t have to buy anything or trade our possessions for potatoes.”

“I think the guards looked through their fingers because they knew the people were hungry and no one supplied food for us.”

Joanna clearly remembers the name of the NKVD forced-labour facility in the Archangielsk region of northern Russia: Szenczuga, near the railway town Konosza. They arrived by cattle-train, its wagons modified to carry people in bulk.

“There was a heater in the middle of the wagon. Each time the train stopped, men from the wagon would go and look for coal and bread, if they could get it.

“A lot were left behind because they were in the shops and the train went without them. I don’t know what happened to them but I heard quite a few families lost their husbands or brothers.”

The men Joanna spoke of were not supposed to get out of the wagons. Armed Russian soldiers guarded them from perches above the wagons, but Poles got out during the infrequent stops.

“I think the guards looked through their fingers because they knew the people were hungry and no one supplied food for us. The soldier walked around the other side of the wagon and people would run out to look for food.

“My brother Bronek was one of them. He was about 16. I was 12. He was a very capable young man. Sometimes he brought back a whole sack of loaves and distributed it among the people. He was lucky that they didn’t catch him.

“In Poland people baked bread for the whole week so some people had bread at first but we travelled for weeks because it wasn’t an express, it was a cattle train and went when it had a chance. Suddenly the line was free and the train went. Many people, especially the elderly and young children died.”

_______________

“They put us in houses built of logs. A big family, they put on one side. Smaller families, they put two together, so we were on one side of the house and they were on the other.

“It was about the size of an average New Zealand bungalow, but it was only one room. Along the walls they had planks, like a long futon, no separation between them, so you slept like that. It was the only furniture.

“In the middle of the house, in Russian tradition, there was what they call a piec, a big stove, but not just a stove. In one part, you have the oven and stove-top for cooking and the other side you make the heat. Of course, it was bitterly cold. You had to keep the fire going all the time.”

“They were not bothering about whether you were hungry or not hungry. It wasn’t their business.”

There were nine in the Adamek-Dybczak family: Joanna, her three brothers and parents, her mother’s parents and her grandfather’s brother, Wojciech, then aged 64. The NKVD commandant running Szenczuga soon corralled her father and brother Bronisław into the “labour for bread” regime. They disappeared into the taiga to cut trees and returned “maybe” once a month.

“They said they went to an old Russian settlement for people deported before us, White Russians. Stalin punished people if he thought they were a little bit better off than others, or said political things he didn’t like.

“Most of them died there. They called them tubylczy, which means locals, people who stayed there for years, from family to family. They usually had a goat or two, and the same kinds of houses as us, but they had cultivated quite big gardens—enclosed—where they grew potatoes, tomatoes and cucumbers.”

For their labour, Franciszek and Bronisław Adamek received 500 grammes of heavy brown bread a day, some of which they saved to share with their family back in Szenczuga.

The facility provided a daily slice of the bread to those who did not labour.

“Occasionally they gave us ‘soup.’ Brown macaroni in water, and they called it ‘soup.’

“There wasn’t anything to buy. The only thing they were selling was a bit of brown bread and salt, and sugar at Christmas and Easter. The sugar was rationed and in lumps. There was no milk. They were not bothering about whether you were hungry or not hungry. It wasn’t their business.”

It is not clear what Roman did. Joanna is certain he did not go with her to school, which stopped at year four. At the NKVD facilities, all teenagers joined the compulsory workforce at 15, an age Roman reached only a few months before the family left.

_______________

Soon after they arrived in Szenczuga, Józef Dybczak started coughing and complaining about pain.

“I think he had pneumonia. There was a hospital but he didn’t go. They gave sugar for every illness. He lay in bed for quite a long time. One day my grandmother asked me what he was talking about because he kept saying he is going, he is going. Then she asked him where was he going? He said, ‘To God.’

“That was on 3 May 1940. I remember it as if it was yesterday.10 It stays there. Certain names and certain dates don’t go, and it was the narodowe święta polskie [a Polish national holiday, celebrating the declaration of the Polish constitution on 3 May 1791].”

Joanna recalled her great-uncle Wojciech Dybczak dying that August after a similar but shorter illness.11 She blames her age for not remembering more.

“The Russians used to say, ‘In our country we have summer, summer all the time.’”

“Being 12 or 13, you look differently on a situation. Grown-ups had to worry about providing food, but where do you get it from if there is nothing?”

Her parents managed to buy a goat from the Russian tubylczy to provide Jan, then five, with milk.

“They exchanged a pair of shoes, or an eiderdown. That goat made just enough milk to give Jan a bit every day, not enough for anyone else. I can’t remember where it stayed, but it was probably in the house in the winter.

“The Russians used to say, ‘In our country we have summer, summer all the time.’ Spring, summer and autumn came in those three months. There wasn’t enough time to ripen the tomatoes, which is why the tubylczy had green, salted tomatoes in their barrels.”

_______________

Suddenly Franciszek and Bronek returned, released as part of Stalin’s ‘amnesty’ after the signing of the Sikorski-Maisky agreement on 30 July 1941. (For more details, see military timeline on this page.) The surviving Adamek family, with Franciszka Dybczak and other Poles, followed directions to travel south to one of two enlistment stations.

Joanna cannot remember leaving Szenczuga—NKVD documentation gives a release date of 2 September 1941—but knows that they got to a place she remembers as Jakubak.12

There, Uzbekistani locals grew cotton and lived in what they called kibitki, round tent-huts made of clay with no windows, and thatched rooves with round holes in the middle for air. The Polish army allocated the Adameks to one empty because the previous occupants had died.

“The huts were full of typhoid germs, but no one disinfected anything.”

Heat made sleeping outside more bearable. Joanna remembers the scurrying tarantulas and the first time she came across hefty snakes slithering through the cotton fields.

“There were so many snakes, because we lived among the cotton fields, but normally they didn’t bother us—not like the green and black mambas that lived in the trees in Durban.”

To survive, they bought food from the Uzbeks or exchanged “things” for milk. By then, they did not have much left to barter with besides some of the warmer clothing they did not immediately need. They lived from day to day. Joanna ate yoghurt made from horse’s milk, and the local round unleavened breads. There were no shops.

“My father got typhus and was away for two months. We didn’t see him and we couldn’t visit him. Jakubak was the closest town but we couldn’t go there. People didn’t move around. The only transport was donkeys but that was for the locals. We thought that my father had died because we didn’t hear anything about him. Then one day, they brought him back. That’s when we knew that he was alive.”

Joanna estimates that her family stayed in Uzbekistan for about a year. If they left Szenczuga close to 2 September 1941, they would have been among the first to get to the Polish army’s enlistment stations. Szenczuga was on the southern border of the Archangielsk region, and nearby Konosza, on one of the main rail connections.

From Uzbekistan, the Adameks joined one of the Polish military transports to the port of Krasnovodsk (now Turkmenbashi, Turkmenistan), more than 1,500 kilometres west. The Polish army arranged for two mass evacuations of Polish soldiers and civilians from the USSR in March-April and August-September 1942. All kinds of shipping vessels left Krasnovodsk laden with Poles, and headed south across the Caspian Sea to Persia (now Iran).

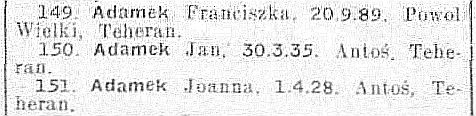

The Red Cross list of Poles evacuated from the USSR (Osoby wyewakuowane z ZSSR Lista Nr 1.) shows that Franciszka, Joanna and Jan travelled together, and Franciszek and Roman each travelled separately. This suggests that Franciszek had already joined the Polish army and Roman the junaki. Bronek is not on the list, which means he could have already been in England training with the British Air Force.

The three Adamek entries on the Red Cross list of Poles evacuated from the USSR all appear on the first page. The list shows dates and places of birth, and destinations. It has, however, aged Franciszka Adamek by 10 years, and misspelt the name of her birth village.

Joanna’s grandmother Franciszka Dybczak did not follow the other Adameks to Persia either. She went to a “rest home” in Uzbekistan and returned to communist-controlled Poland after the war. Joanna believes she may have been in hospital and too ill to leave Uzbekistan with the rest of the family.

“She wrote letters to us from Poland. She was quite happy there because she was still able to do things. She helped in the kitchen, cooking, and she enjoyed that. My brother Romek brought her to England in 1950. She stayed with my mother and father, and she died there.

“In Pahlevi they put us in tents and looked after us. We had common dining rooms. They fed us porridge, bread and cheese and sardines—regular food—and for the first time, I had a cup of white tea. Like the saying goes, ‘darowanemu koniowi w zęby się nie zagląda’ [don’t look a gift horse in the mouth], and we were grateful for whatever we got.

“We stayed in Pahlevi for a while, then went to a camp near Teheran. We could walk into the city and I remember the main posh street, named something like Lalazara or Lelezara, a kilometre or two from the main town centre. The shops were full of beautiful things, and you had not a penny in your pocket.”

Joanna, left, and her friend Anna Krycka in Teheran, circa 1943. Although much milder than

in northern Russia, the Persian winters were frosty.

Joanna attended the gimnazjum humanistyczne (college teaching the humanities) and Anna the gimnazjum handlowe (college

teaching commercial subjects).

“We lived in barracks, like the soldiers, no proper beds and curtains dividing the bedrooms. It was lucky when they put us where the soldiers were before because we did not have to sleep on the floor.”

_______________

Franciszka, Joanna and Jan Adamek arrived in Southampton on another 3 May, this time in 1948.13 The carnarvon castle carried 1,200 what it termed “displaced persons… mostly women and children and the elderly” from then Rhodesia, Tanganyika and East Africa, and put them into the care of the Polish military authority in England.

They joined Fanciszek Adamek, already demobilised and living in a Polish resettlement camp near Wymeswold,14 site of a WW2 airfield. The vacated barracks housed the Adameks for “quite a few” years. Roman lived with them briefly. He went to school, then university. Bronisław remained with the British Air Force until he retired. He had finished training in 1945 and had been due to go on his first bombing mission to Germany the day after the war ended.

The Adamek family never again lived together. Franciszek and Franciszka moved to Loughborough. Roman lived near Liverpool and Bronisław moved around the UK with different commissions. Joanna and Jan lived with their parents and babcia Franciszka.

“In Aylesbury, close to London, there was a Polish grammar school and I finished the two years before you go to university there, as a boarder. They pressed us to learn English so that’s where I learnt quite a lot about the English language—but I still could not speak. You have to mix with the people to learn how to speak.

“I loved history, geography, chemistry and Polish. I should have gone to university but I wasn’t courageous enough to go on my own. I had university entrance to go to Strasbourg, in France, but I didn’t feel I could stand on my own feet. I was always a shy person and close to my family. I was too scared to go.”

The cooking/home economics classes offered to her in England did not interest her. Instead, she worked as a clerk in an accounts department until she married in 1953. Joanna met her husband through Roman.

“I was going somewhere with Romek in Loughborough and we met Tadek [Kalinowski]. They started chatting, and that was that. A week or two later, he started visiting me at home.”

Joanna Adamek and Tadeusz Kalinowski. Tadeusz recalls they met on 18 April 1949, and that Joanna accepted his marriage proposal on 3 September 1951.

Joanna and Tadeusz Kalinowski on their wedding day, 1 August 1953.

_______________

England’s climate did not suit Tadeusz Kalinowski, whose time in northern Russia made him susceptible to pneumonia and pleurisy. He, his younger brother, Kazimierz, and his parents, Adam and Eufrozyna (née Suszko), travelled much farther north than the Adameks and the Dybczaks.

According to NKVD records, the Soviets removed 132 Polish civilians—24 families and two single men—from the Białystok-Baranowicka region of eastern Poland. If they got off their cattle train just short of the Arctic Circle, they still had more than 100 kilometres to navigate westwards in sub-zero conditions to get to Tuszyłowo, one of the NKVD’s most remote facilities in Archangielsk.15

At least 100 kilometres of taiga and lakes sit between Tuszyłowo, on the north-east of Lake Kożoziero (Kozhozero), and the closest railway link on the railway line, which in 1940 ran from Konosza north to Onega. The substantial Onega river runs halfway between that railway link, Letnieoziorskij, and Tuszyłowo. The records state that the Kalinowski family were removed from their home on 3 March 1940, so the Onega would still have been frozen by the time they had to cross it. A satellite image today shows no discernible remains of human activity around the lake, or at the NKVD Połowino forced-labour facility, even farther north.

Like Joanna, Tadeusz clearly remembered memorable places and dates. He jotted down some of them after a trip to Poland in 1997.

After hearing about the ‘amnesty,’ Tadeusz, his father, and nine others from Tuszyłowo joined the Polish army in Buzuluk in southern Russia. By the time General Władysław Anders made his first visit there in September 1941, 17,000 Polish men had already arrived.16 Tasked with setting up the Polish army in the USSR, General Anders soon saw how inappropriate the site was. By December, the “temperature dropped to minus 52 degrees centigrade and icy winds swept the snow into drifts. Many of our men froze in their tents,” yet the Kremlin delayed their move south “by every possible pretext.”17

Tadeusz enlisted with the Second Polish Corps on 2 January 1942, a month after his 17th birthday. He told his eldest son, Bogdan, that his father’s age (48) made him too old for combat, so the army sent him to Egypt, where the British trained him in logistics. Tadeusz left Krasnovodsk on the Caspian Sea on 13 August 1942, bound for Pahlevi, where he “accidentally” met his mother and brother Kazimir.

The arrival schedules of evacuation vessels into Pahlevi showed the Polish army under pressure to get as many Poles out of the USSR as quickly as possible. It had taken months to organise a second evacuation through Krasnovodsk, and Polish officials knew the Soviets were closing the window for their escape. Vessels carrying Poles started arriving in Pahlevi on 10 August 1942. Four days later, at least three large ships carried more than 12,000 Poles—including Tadeusz—to safety. One ship held 4,147 troops from the 6th and 7th Infantry Divisions. The other two accommodated 2,653 civilians with military enlistees of the 5th and 7th Infantry Divisions, and army staff.18

Tadeusz spent only a few weeks in Pahlevi before he moved to Khanaquin in Iraq, where he had another “accidental” meeting—this time with father—on 16 September 1942. He then settled into military life at the Polish army-training centre near Qizil Rabat.

General Anders remembered the Polish headquarters there as “several primitive little huts… surrounded by a sea of tents pitched on the sand of the desert… Our soldiers… never complained about the epidemics, the heat or the desert; they only grumbled about the slowness in the arrival of arms and equipment and the consequent delay in their training… Our chief task was mechanising the army, which meant that 20,000 drivers had to be trained.”19

The 3rd Carpathian’s Rifle Division, Infantry Brigade, and Lancers arrived at Qizil Rabat, and instructed two reconnaissance regiments, the 12th Podole Lancers, and the 15th Poznań Lancers,20 formed in Yangi Yul under the leadership of Major Zbigniew Kiedacz,21 which Tadeusz joined.

In 1943, he left Qizil Rabat for courses in radiotelegraphy, gunnery and tank commanding at the El-Abaseya British training centre in Cairo. By then Kazimir was at the nearby Heliopolis airbase, and the brothers met again. Tadeusz returned to his regiment and more training on armoured cars and Bren carriers in Egypt, Palestine, Syria and Lebanon, and left the Middle East from Port Said.

The Polish army sent 50,000 troops to Italy. Tadeusz arrived in Taranto on 21 February 1944 and left on 23 March—a date he remembered for the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. “Action” in the Sangro river–Gamberale area farther north included his squadron’s eliminating a German artillery observation post.

The regiment moved to the Monte Cassino area on 1 May 1944, and was “soon in action attacking Pazzo Carno22 with a squadron of Carpathian Ulans [lancers] where we took 42 Germans.” Tadeusz recalled that seven Poles died that day, and 25 were wounded. General Anders wrote of the “fight not yet finished” after the final battle for Monte Cassino itself, which the Poles tied up on 18 May with the Polish flag flying on the monastery ruins. A few kilometres west, the Germans had created a “fortress” out of Piedimonte, on the Hitler Line and protected by Pazzo Corno and Monte Cairo, whose “rocky and steep approaches, quite without shelter from enemy fire and observation, made the task a very difficult one…”23

Tadeusz was wounded on 17 July 1944, during the battle for the Adriatic port of Ancona. His father visited him in hospital in Bari, but Tadeusz made an impatient patient. He escaped from the convalescent camp, on the beach back at Taranto, “still with the bandages on” and on 27 September 1944, re-joined his regiment, which “resumed front action” at Civitella Di Romagna. Tadeusz remembered 23 October 1944 as the day that his regimental commander Kiedacz died while crossing a mined river in a jeep.

_______________

After the war in Europe ended, Tadeusz, like many other younger Polish servicemen in Italy, attended college while he waited for British politicians to make decisions about his future outside Poland. The British Eighth Army had integrated the Polish Second Corps in Italy, and therefore its service personnel became British post-war responsibility. Tadeusz, like most of the Poles in the Second Corps, refused to return to a communist-controlled post-war Poland.

He arrived in Liverpool in August 1946, and continued his studies in Barnsley until he was demobilised a year later and started working. A year after that, he took on a four-year course in chemistry and dyeing, and noted that on 18 April 1949, he “met Miss Joanna Adamek for the first time.”

Joanna: “Tadek loved hot climates. He loved the Middle East. He loved Egypt. He loved Iraq. He loved Italy but the English climate wasn’t good for his lungs. He applied for jobs in Africa, in South Africa and Canada. Of course, Canada wouldn’t be any better than England, so he picked South Africa. He went to Johannesburg for close to a year in 1959 but he didn’t like it there.”

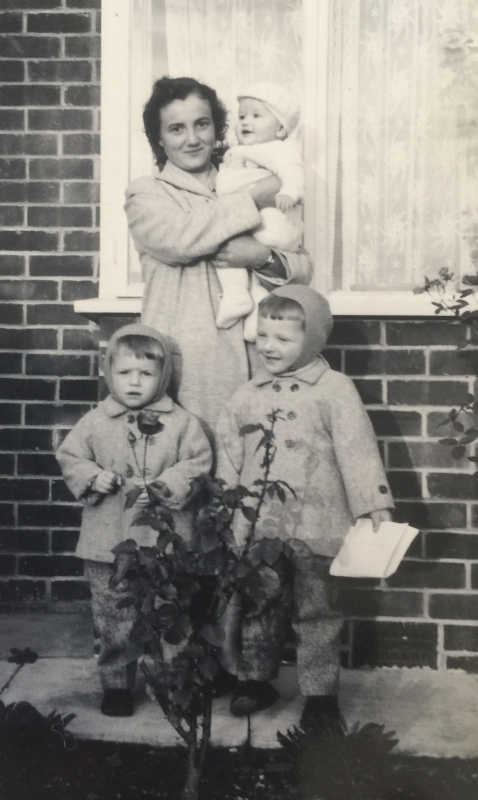

Joanna holding a nephew in Loughborough, England. In front of her, right, is her son Bogdan (Bob) and an unnamed child.

“On the way back to England, he stopped in Durban. He liked the look of the sea city, much warmer than Johannesburg, so he stayed there for a week and started looking for a job. He worked in textiles and saw an advertisement for a dyer and went to the factory, which happened to be owned by a Polish Jew. He gave Tadek a job straight away and he had to call his baggage back because it was already on the ship ready to go back to England.

“The owner of the factory gave him a nice three-bedroom house and he wrote to me, ‘Get ready, bring children.’”

Joanna had been living with her in-laws and in 1960 travelled with her sons, then 3½ and 2½, to Durban, where Krzysztof Piotr (Peter) and Anna Maria were born.

Joanna in Durban circa 1970 with, from left, an unnamed child and children Anna, Peter and Bogdan.

“If it wasn’t for the political situation perhaps we would have stayed longer in South Africa because he loved the climate and he loved the job and the children loved it too. I didn’t like it. For me it was too hot in summer.”

In 1973, Tadeusz again left Joanna and the children—to investigate advertisements for his trade in New Zealand and Australia. Tadeusz chose New Zealand and Joanna arrived in Auckland with three children.

“I thought New Zealand was paradise because it was so green and so beautiful and not hot. We arrived on 21st December 1973, and it was a beautiful summer that year. I was still wearing a thin summer dress in May. Normally in May it’s getting cold in South Africa and here I still had on a summer dress.”

Tadeusz and Joanna bought a little shop, Windmill Dairy, in Mount Eden Road, which Joanna ran with Tadeusz’s help after work and at the weekends. The family lived in the two bedrooms at the back until they found a villa in Fairview Road for $34,000.

The huge house had been divided into two units. The orginal walls were made from sacking covered with wallpaper. Tadeusz renovated with proper gib-stopping and paint during time off from his job as a laboratory technician in a clothing factory.

“My daughter was only seven when she went to school here in Mount Eden. She had a hard time because she was from South Africa. She used to come crying from school because she couldn’t make any friends. Gradually she managed but people from South Africa weren’t welcome here.

“Bogdan was with us for one and a half years. He attended university here and corresponded with friend in South Africa, from Maritz Brothers school and with a South African girl.

“They married and he brought her here with the intention to settle but she didn’t like New Zealand. She was born in South Africa, and the life there was much easier for white people than here. They went back to South Africa and he is now in Australia.

“I thought New Zealand was beautiful and the people we met were very nice to us. When we bought that shop, there was an elderly widower living in the other flat, because the shop was divided. He was very kind and helpful. He knew the attitude of New Zealanders towards the people who thought we were South Africans. We weren’t, but we lived there.”

Joanna and Tadeusz greeted Anna and her new husband, Andrew Swain, as they entered their reception in 1999, in the traditional Polish way: a special tray with bread, lightly sprinkled with salt, and vodka. The bread represents the wish that the newlyweds would enjoy abundance in life; the salt represents a power to heal and is believed to discourage bad spirits; the vodka represents a wish for good health and good cheer for their joint future.

Anna and Tadeusz Kalinowski at their daughter Anna’s wedding in Auckland in March 1999.

Tadeusz died in 2005. Franciszek and Franciszka Adamek lived out their lives in England, as did Bronisław and Roman. Jan, now a widower, still lives in Loughborough.

Although Bogdan does not live in New Zealand, Joanna says in contact with him through the phone and Peter and Anna are regular visitors at the rest home where she now lives, as are Anna’s two sons, Łukasz and Kazik, with their babcia below.

Joanna has little space these days to surround herself with physical mementoes of her life but it does not worry her—she keeps her images in her mind. She may be getting more physically frail but she keeps that mind exercised with the world’s goings on through daily newspapers and the television.

The sparkle in her eyes remains.

© Barbara Scrivens, 2019

Updated August 2020.

THE PERSONAL PHOTOGRAPHS ARE FROM JOANNA'S DAUGHTER, ANNA SWAIN. OTHER IMAGES ARE CITED BELOW.

THANKS TO THE NORTH AUCKLAND RESEARCH CENTRE IN THE TAKAPUNA LIBRARY FOR THE LOAN OF AUDIO RECORDING EQUIPMENT.

ENDNOTES:

- 1 - On 18 March 1945 an earthquake in central Uganda killed five people and destroyed

buildings in Masaka, about 240 kilometres directly south of Masindi.

http://www.unesco-uganda.ug/files/downloads/Ethquakes%20in%20Uganda.pdf - 2 - Narodny Komissariat Vnutrennikh Del (People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs)

- 3 - These figures come from the late Jagna Wright, who spent the last 15 years of her life

researching the background for the film A Forgotten Odyssey, the Untold Story of 1,700,000 Poles Deported to Siberia in

1940, which she wrote, directed and produced with the late Aneta Naszyńska.

For a more in-depth discussion on numbers, see Missing Humanity on this page. - 4 - I use this word in single quotation marks to suggest that General Sikorski knew full well that the incarcerated Poles, although political prisoners, had done nothing to deserve their incarceration.

- 5 - Anders, Lt-General W, CB, An Army in Exile, originally published in 1949. Reprinted by The Battery Press, Nashville, ISBN: 0-89839-043-5, page 113.

- 6 - Map from Skradzione Dzieciństwo by Łucjan Z Królikowski, OFM Conv., Wydawnictwo Apostolstwa Modlitwy, Kraków. English version translated by Kazimierz J Rozaniatkowski.

- 7 - KARTA's general photographic website available on: http://www.foto.karta.org.pl/

This particular photograph was donated by Maria Wierzchowska and is numbered OK_005207:

http://www.foto.karta.org.pl/przeglad-wynikow-wyszukiwania/?allword=Masindi&exactmatchword=&anyword=¬hiswords=&imageselected=4093 - 8 - Photograph by A Torres. Published on the website of the Embassy of the Republic of Poland

in Nairobi, 21 December 2018.

https://nairobi.mfa.gov.pl/en/news/a_visit_to_the_polish_church_in_masindi - 9 - Franciszka’s birth name was Holboj.

- 10 - The date of Józef Dybczak's death is confirmed on the KARTA Indeks Represjonowanych,

https://indeksrepresjonowanych.pl/int/wyszukiwanie/94,Wyszukiwanie.html - 11 - Ibid. The KARTA Indeks Represjonowanych shows that Wojciech Dybczak died on 15 August 1940.

- 12 - This may not be the correct spelling. If anyone knows more, please get in touch through our home page.

- 13 - List through the website Polish Resettlement Camps in the UK 1946–1969,

http://www.polishresettlementcampsintheuk.co.uk/ - 14 - This could have been part of the Polish Resettlement camp in nearby Burton on the Wolds.

- 15 - Information through the Karta Indeks Represjonowanych, ibid above, and the 1949-1941 map by Aleksander Gurjanow of the forced-labour facilities holding Polish civilians in the Archangielsk region.

- 16 - Ibid, Anders, pages 63 & 64.

- 17 - Ibid, page 94.

- 18 - Information from a report by Lieutenant Colonel Stanisław Lecher, attached to the British Base Evacuation staff who corroborated in the second evacuation of Poles from the USSR, appendix B.

- 19 - Ibid, Anders, pages 131 & 132.

- 20 - Ibid, page 133.

- 21 - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/15th_Pozna%C5%84_Uhlans_Regiment

- 22 - Anders, ibid page 180. General Anders spells this peak Pazzo Corno and Passo Corno. It is

probably the area known as Hill 893. Follow the Poles’ 1944 Italian campaign at:

https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/1944-2/ - 22 - Ibid, Anders.