Joe Gratkowski

SIXTH HOME LUCKY

by Barbara Scrivens

A hut in the middle of a snow-covered field in the Ural foothills hid something more valuable than gold to the Gratkowski family.

It stood slightly apart from the main buildings of the NKVD forced-labour facility that incarcerated several hundred Poles during World War 2. (The NKVD, or People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs, were Stalin’s Secret Police.)

The hut stored vegetables and grain for planting the following season. Near the end of the winter of 1940-1941, the facility’s NKVD commandant decided that the inmates had “over-eaten” and put a two-week halt on distributing rations.

After a week with no food apart from what they had been able to scrounge, 15-year-old Bronek, the Gratkowskis’ oldest child, took up the hut’s challenge.

Bronek knew intimately what was inside—he had helped fill it at the end of the summer harvest. He also had a copy of the key to the storeroom door in the basement.

During his time at the facility, Bronek had gained a reputation as a reliable worker, and when the commandant stopped the rations, he asked Bronek to lock the door on the mounds of potatoes, carrots, wheat and barley.

Bronek later told the story to his youngest brother, Joe:

“It was an old-fashioned key with a hole in the centre. He had a bit of soap cake and pressed this key into it, so it left an imprint. Then he got a bit of tin and he started to make his own key. When he made the key, he went to the hut to see if it would fit in the door.

“He went on his skis. He had night blindness, but he said the moon was bright and there was some snow, so he could see well enough. The key didn’t fit the first time, so he went home and filed it a bit more. He went a second time and the door opened.

“He told father what he had done and father made him a hollow sack, to put over his back. He also told a friend from another Polish family, and they went to the hut together, at night and on skis.

“Before they went Bronek organised with other boys to ski all around the hut, so there were a lot of ski-marks. That night he took some potatoes and some barley and loaded the haversack. He put it on his back but he couldn’t get up, so he had to start emptying and only took what he could carry.

“He got home of course, and Mum started making soup and different things and we all had a good feed and revived a bit. A lot of the Polish families died when the rations stopped. Life meant nothing there, nothing. You were just a slave.

“We survived. Dad borrowed a millstone so he could mill the wheat and Mum was making bread and slicing it and drying it out—sucharki—so we could carry it and have it at a later date.”

_______________

Before the war the Gratkowski family lived carefully on their farm in Krzywe, near Skałat in eastern Poland, just 12 kilometres from the then-Soviet border. Michał and Karolina Gratkowski (née Grynienko) had nine children, the eldest, Helena, having died about aged eight.

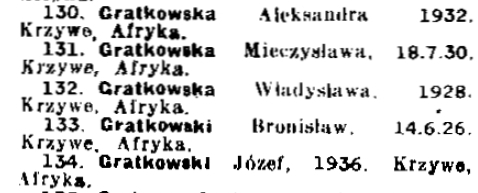

Although he is unsure of their exact ages, Joe remembers about two years between the siblings. His grand-nephew, Cameron Bourgeois, found the Krzywe birth records and verified eight of the children’s birthdates: Bronek (14 June 1925), Helena (1 November 1926), Władysław (22 September 1928), Mieczysława (1 July 1930), Aleksandra (14 April 1932), Stanisław (25 September 1934), Joe, or Józef, (27 September 1936), another Helena (20 August 1937). Piotruś, born in January 1940, does not appear with his siblings on the Krzywe records.1

Karolina Gratkowski sits on the left, with her mother next to her and her sister behind. In front is Helena, born in 1926, and Bronek, born in 1925 in Malinówka. Bronek’s name also appears in the Krzywe birth index, with seven of his siblings, which suggests that Karolina may have given birth to her first child at her mother’s home in Malinówka. One of Joe’s sisters in England has the original photograph.

According to the scale, Malinówka was two kilometres west of Krzywe. This map is part of a preservation project by MapyWIG, one of hundreds drawn and printed in the 1930s by the Polish Military Geographical Institute (1919-1939), and which show details such as churches and individual dwellings, forests, swamps, tracks between villages, and railway lines.2

The farm had cherry and apple trees, a few cows, pigs, a horse for ploughing, and stables. Although the family was self-sufficient as far as food went, they bought other necessities through selling produce such as butter.

The children kept themselves amused in the farmyard, watched over by their dog attached to a wire that ran the length of their property. Carefree dress-up games included little brother Joe running around in a too-long dress.

Joe knows that their grandparents lived nearby because Bronek used to visit them.

Joe was three when Soviet soldiers barged into their farmhouse one winter’s night, after the Russian invasion of Poland in September 1939, and ordered Michał to pack some belongings. Joe remembers the soldiers forcing the family into a sleigh, taking them to a railway station and loading them into a crude transport wagon that meandered towards Siberia.

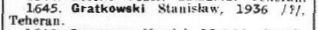

He does not remember the exact date, only that it was winter. Years later, when he wondered about his birthdate, Bronek told him it was 10 February, significant because it marked the expulsion in 1940 of more than 200,000 Polish civilians, mostly from rural areas in eastern Poland, into forced-labour facilities in northern Russia and Siberia. The Polish birth certificate Joe received years later showed his birthdate as 26 September 1936, so Bronek’s recall of 10 February, and Joe’s specific memory of the dark and freezing winter, points instead to when the Soviet soldiers arrived at the Gratkowski farm.

Piotruś did not survive the train journey.

“There was nothing to eat at all, so mother fed him and Helena on sugar water.

“The train didn’t travel directly to wherever it was going. It would stop, maybe for an hour, or it might stop for two days, and so people would get off and go to the villages to trade for food.

“Bronek joined father in the forest but it was winter… he tore his clothes faster than he could earn money to replace them…”

“When the train stopped after Piotruś died, father had to knock up a little coffin and bury him near the tracks somewhere.

“I remember being in the train, divided along the walls with three wide beds. Each bed was allocated to a family. We probably occupied two or three of them… I was on the top bunk…

“There was a fire, a bot-belly in the centre. They had it alight to keep the wagon warm… and in the corner there was just a hole for the toilet…”

The train eventually stopped at a kolkhoz in the Ural Mountains. In collective farm tradition, the local inhabitants grew food for the village as a whole, gathered the harvest and kept seeds for the following season. An NKVD commandant ran the forced-labour facility in the forest where the Poles worked for a daily ration of bread.

“Bronek joined father in the forest but it was winter… he tore his clothes faster than he could earn money to replace them so father decided it was no good to have him working because it cost more if he worked than if he didn’t.

“My oldest brother was quite clever. He made skis and sold them to the local boys so he could buy food. Wood was plentiful; we were in a forest. He boiled the ends and bent them up to make skis. The commandant didn’t have anything against it. His son probably rolled on those skis.”

Bronek’s ski-making enterprise and flair for engaging with the local Russians and his captors no doubt prolonged his family’s lives and the lives of his Polish friend’s family. However, the storeroom theft made Bronek an obvious suspect and both families vulnerable.

Germany’s Operation Barbarossa saved Bronek from discovery by the facility’s NKVD commandant. Hitler turned on his ally Stalin, and suddenly pushed his troops across Russian-occupied Poland from 22 June 1941. With the Germans on course to attack Moscow, Stalin swapped allegiances.

“We heard after we were in Persia that they were looking for us in Russia.”

The Sikorski-Maisky agreement signed on 30 July 1941 between Polish Prime Minister Władysław Sikorski and Soviet Ambassador to the United Kingdom Ivan Maisky saved the lives of hundreds of thousands of incarcerated Poles.

The agreement allowed the Poles to leave their forced-labour in the USSR to join a Polish army being formed on Russian soil. Michał Gratkowski immediately organised train tickets for his family.

“We knew we had to get out quickly. If the commandant had discovered the theft, he would have sent us deep into Siberia, the goldmines somewhere…

“We heard after we were in Persia that they were looking for us in Russia. Obviously when they went into the store in the spring, they noticed that quite a bit of it was missing.”

The same nine Gratkowski family members who had walked into the kolkhoz 18 months earlier, walked out “across the meadows” in the direction of the train station.

“My oldest brother was quite musical. He played the guitar and he played the mandolin and had a balalaika as well. The Russians like to sing comical, ‘dirty’ songs, and being a teenager, he joined the younger generation in clubs and learnt the songs. He could speak fluent Russian and played music, so he was quite popular, and we could spend the night in this attic or that room.

“They had irrigation canals. We thought one was a ditch, nice and gentle, so we spread about with our suitcases and blankets and whatever, to spend the night. Bronek got up when the sun rose and walked ahead. He could see the water coming…

“He was running towards us and shouting: ‘The water is coming! Get out! Get out quickly!’ I got out and everybody else did as well but all the little bundles, mandolin and guitar—everything floated off.

“There was Stan sitting on the bank hanging on to two suitcases, so Bronek helped him get out and they walked on to pick up the bits that had floated to the end. The mandolin and guitar were broken—all the glue had given way. They were no good for playing. We couldn’t even carry them, and we still had about 70 kilometres to walk to the station.

“We got to a station and father told Bronek to stay and watch the suitcases, so he sat on one suitcase and had all the other suitcases close to him.

“I don’t remember my dad at all. Odd, but even in Poland he would be working the land all hours of the day.”

“He could see the local boys, just waiting for him to fall asleep. He was tired and dropping off, and he knew that they would pinch whatever they could if he did sleep, which he did and they did.

“When he woke up, everything was gone. He was left with the suitcase that he was sitting on.”

One of the stolen suitcases held the family documents, including birth certificates. After Michał and Karolina died, it fell to Bronek to remember each of his siblings’ birthdays.

Joe is aware that his memories of getting out of the USSR remain out of sequence. He does not remember which of his parents died first, but neither left the USSR.

“I don’t remember my dad at all. Odd, but even in Poland he would be working the land all hours of the day.”

On their way out of the USSR, they stopped at “many different places.” Joe does recall a Polish army camp near Bukhara.

“They were meeting all the people who were coming in. We could go and have a hot shower. They gave us some new clothes. They piled all our old clothes in a square and set them alight. They were full of lice. People had lice all over. You could see them crawling in our ears, but you are cold and you wrap yourself up and of course there was no means of having a bath or shower.”

In the NKVD forced-labour facility, Karolina Gratkowska had been without her heart medication, and was admitted to hospital at one of the places they stopped. Bronek went to visit her a few days later.

“They told him she had died, so he didn’t even see her. Then, somewhere in Uzbekistan, Bronek got sick as well. He was delirious. He said that he could hear his father’s voice from the bottom of a well, so he was going to jump in to save him. It was a very deep well with water at the bottom, and he nearly jumped in, but a Polish man grabbed him and stopped him.”

If Michał did manage to get to a Polish army enlistment camp, the record seems to be missing. Bronek lead the surviving children to the Polish authorities, who from then on, organised their lives.

They left the USSR through Turkmen SSR (now Turkmenistan) and the port of Krasnovodsk (now Turkmenbashi) on the eastern shores of the Caspian Sea. The Polish army arranged two sets of evacuations of soldiers and civilians in March–April and August–September 1942.

Six of the Gratkowski children appear on a list of Polish families evacuated from the USSR in August 1942: Bronisław, Władysław, Mieczysława, Aleksandra and Józef, mis-named Gradkowski and destined for Africa, and Stanisław Gratkowski farther down on the same page.3

“The ship was full of people on deck. Some fell overboard and drowned. They never stopped the boat; just carried on. We were all sick or weak and if someone sat near the railing and slipped out, that was it…

“We finished up in Persia. It was a different climate, warm, just rooves with piles [upright posts] and you had a blanket and you could lie down anywhere on the sand and sleep. The sea was nearby and a lot of people went into the sea to wash or play.”

It is not clear what information Bronek had regarding the options for his immediate future, or that of his siblings. Authorities would have moved them out of Pahlevi, a temporary holding area, to Teheran, where several tented camps for the Poles had been set up. With regular meals and proper medical attention, the Gratkowski children started to recover their health.

At their ages, at least Bronek and Władysław would have qualified to join the junaki, the military cadet school set up by the Polish army for Polish teenagers. It seems that Bronek sacrificed that opportunity in order to keep the siblings together.

“Because the war was still going on, if there was an available ship, it took some refugees. If a country accepted them, they would load some on board and they would go off.

“The Polish people in charge of the whole camp in Teheran had a doctor who examined everybody to make sure they were healthy enough to travel. If we were healthy, we could go. Bronek was not supposed to come with us, because the shipment was already full, but they were going to take the rest of the family, except Stan and Hela. Overnight a boy about Bronek’s age died—he was on the same transport—so the lady in charge called him to the office and said, “There’s a place for you to go, but you have to go as such and such.’ He told me the name, but I don’t remember.

“An American ship took us to India. We stayed in port a week or two and then they decided to put us in an African camp in Tanganika [now Tanzania], Tengeru. We stayed there until ’48 when we went to England.

“They left Stan and Hela in Persia because Hela had a very bad case of rickets. She couldn’t walk, so Stan carried her wherever she wanted to go. Her legs were very bad and she had that round stomach you get from malnutrition. Stan had rickets too, which is why he stayed. When Stan came to New Zealand [in 1944], Hela was still left behind.

“Stan located us through the Red Cross. We were already in England. We tried to locate Hela but we never found out where she was. We lost her. Being younger still than I was, I don’t suppose she would even know her name if somebody adopted her.”

Stanisław appears in the list of Polish children in Isfahan4 but Helena does not, suggesting she may have died in Teheran or was adopted under another name. The Red Cross list of evacuees from the USSR indicates that five Gratkowski siblings went to Africa some time before Stanisław went to New Zealand. Stanisław’s details farther down the list are more sketchy and date of birth incorrect, showing how difficult it would have been for a child his age to remember his or her own background. Stanisław was born in 1934, not the 1936 on the Red Cross list.5

Stanisław Gratkowski arrived in New Zealand with 732 other Polish children, many of them orphans, and 105 Polish caregivers on 1 November 1944. (See blue skies, green grass and warmth.)

_______________

Under Mount Meru, and with occasional glimpses of Mount Kilimanjaro in the distance, the Tengeru camp accommodated around 4,000 of the Poles from the USSR.

Joe has fond memories of the “jolly” sergeant Zajder [possibly Zajdel] in charge of the orphans.

At first the children stayed in round huts, or rondavels, that Joe recalls the local Swahili called “neumane.”

“There was one hut per family, a door on one side, and on the other side was a window with wooden shutters you could close at night, and beds. To build the huts, they drove three-inch posts into the ground about a foot apart in a circle, and then they had sticks about one inch or thinner and wove them in-between. When that was all woven, they took mud and straw and plastered both sides all the way up, smoothed it off and whitewashed it. The floor was dirt. They used branches from coconuts as a roof material, tied up in the centre, and had coconut mats specially made for roofing. Once the termites got into it, of course they would eat the wood and the roof would leak.

“There were two orphanages in Tengeru, a girls’ orphanage and also one for boys and girls, where I was.

“After the huts, in the second camp we had a very long dormitory, girls on one side, boys on the other and in the middle there was a room for the lady who was in charge. She had a door to each side.

“Termites had a nest nearby. They got into the piles of the house and ate all the wood, so when you knocked it with your finger, you could hear that the wall was empty. They used to dig holes to get at the termite queens, to get rid of the nests. They had to dig about five, six feet.”

The remaining Gratkowski siblings settled down to life in Tengeru. As far as Joe knew they had “lost” Stanisław and Helena. After kindergarten, Joe started school aged seven, as was the tradition in Poland.

Joe, right, with a friend in Tengeru.

Bronek left the camp to join the Polish army in Egypt during the latter stages of the war.

“His battalion went to war two weeks before the war ended. He was in charge of the officers’ mess room, and was using one of those spirits lamps when the thing exploded and burnt him all along one side of his body. He finished up in hospital and didn’t see any action at all, but some of his mates that went got killed, so that accident may have saved him.”

_______________

The war ended satisfactorily for the Western powers in 1945 but gave eastern Poland to Stalin, thanks to secret agreements set up by Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin as early as December 1943. This left a reshaped Poland in the hands of a Stalin-sanctioned communist-controlled government. By December 1943 Polish pilots had performed superbly during the Battle of Britain but the relatives of those Stalin ‘amnestied’ in the USSR in 1941 had yet to play their parts in pivotal battles in northern France and Italy.

The 22 Polish camps in Africa held many war widows and orphans originally from eastern Poland. In 1945 those Poles had no homes to return to and no reason to reacquaint themselves with Soviet ‘hospitality.’ British ministers of parliament urged the Poles to return to Poland, but the bulk of the diaspora refused. In 1947 the British government set up a Polish Resettlement Corps and arranged for the Poles in Africa to travel to England.

Władysław (19), Mieczysława (17) Aleksandra (15) and Joe (11) travelled with nearly 500 other “Polish Displaced Persons” from camps in eastern Africa. They boarded the mv georgic in Mombasa and arrived in Southampton on 11 July 1948.

“It was a troop ship, so they bunked us with the soldiers.”

The georgic passenger list6 records the Gratkowski siblings were bound for Woodlands Park Camp number 12, Great Missendon Buckinghamshire. Joe recalls their first stop in England in a disused army camp in Stafford.

“They had no use for it as an army camp anymore. There was also an airport nearby and accommodation for the pilots and crews. Bronek used to visit us in Stafford. He worked in London somewhere growing tomatoes in hothouses.

“I went to school, in Diddington, on my own. That was an American army camp… a big square with a field in the centre and around it all those baraki [barracks]. They used to call them “beczki smiechów” [barrels of laughter].

“They had windows sticking out and a pot-belly in the centre for heat. They were lined inside with pinex and had cement floors and a tarmac that we used to shine. If you had bits of blanket on your feet you could run and slide.”

Once in England, Władysław started to arrange for the Gratkowski siblings to immigrate to America.

“Bronek was in London—he had his own life—so we were going to America. Then Władzio met a nice young lady, fell in love, got married and that was it. I didn’t want to go to America if he wasn’t going.”

Mieczysława and Aleksandra also married and stayed in Stafford. By then Stanisław had discovered his siblings in England and had written to Bronek, who joined him in New Zealand.

Joe left school, returned to Stafford and started working at the Joseph Sankey & Sons Ltd. factory in nearby Shropshire.

“They made tractor tyres and all sorts of heavy machinery. One week I was on day shift and one week on the night shift. I earned ₤2 10s a week. Full board in Britain then was three guineas. I was short of 13s a week so they gave me the job to collect the money off the other passengers for the trip to factory and back. I got 10s for that. I just gave my wage to my brother Władzio and sister-in-law Ala and I lived with them.

“I worked at Sankeys for three or four months and we were promised that we were going to get an apprenticeship in Dursley, Gloucestershire, in a factory called Lister. They made diesel engines, marine engines and things like cream separators and sheep shearing equipment. I started on corrugated milk coolers, did a lot of soldering. When pasteurised milk went through, water cooled it. Then I went to work in an experimental department to do with the engines and fumigators.

“I was earning something like ₤5 a week. My brother Stan from New Zealand says well, he’s started working on the waterfront [Wellington docks] earning ₤16 a week. I said, ‘I’m coming. I’ll save my fare and I’m coming.’

“Bronek’s wife, Krystyna, said, ‘We’ll pay your fare and when you earn the money here you can pay us back,’ so at 18 I came here and joined them, and joined the waterfront after a couple of weeks. I had the interview and I worked there 42 and a half years.”

Joe arrived in Wellington on 13 July 1955, one of two Poles aboard the rms rangitane that carried 403 British and 18 “Foreign” adults, 59 children and five infants from London via “Curacac,” Jamaica and Panama.7

By 1955 Bronek, who had taken a job in a stocking factory, had bought a house in Happy Valley, Owhiro Bay, and the brothers again lived together. Bronek soon joined his brothers at the more lucrative waterfront.

_______________

“In 1955 New Zealand was a very, very quiet country. Everything was shut on Sundays. England was bad enough, but New Zealand was even worse.

“I lived in different countries and then went to Britain and they lived differently. New Zealand was different again but I got used to it and got to like it.

“When I came here we used to go to the Polish Club. They were very organised. They had different functions, so I got to know quite a lot of Poles in Wellington, and there were quite a few Poles working on the waterfront so I got to know a lot of them. I met one guy that I was in Africa with, Joseph Zyskowski.”

Polish functions and dances gave many opportunities for Joe to meet Polish women but he had no illusions about marrying one of them. His friends had told him, “All the Polish girls wanted the English boys. They didn’t want the Poles.”

Heather and Joe Gratkowski on their wedding day, 26 November 1960.

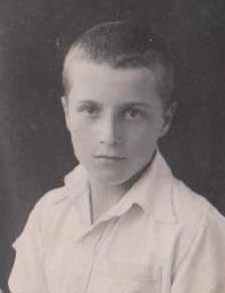

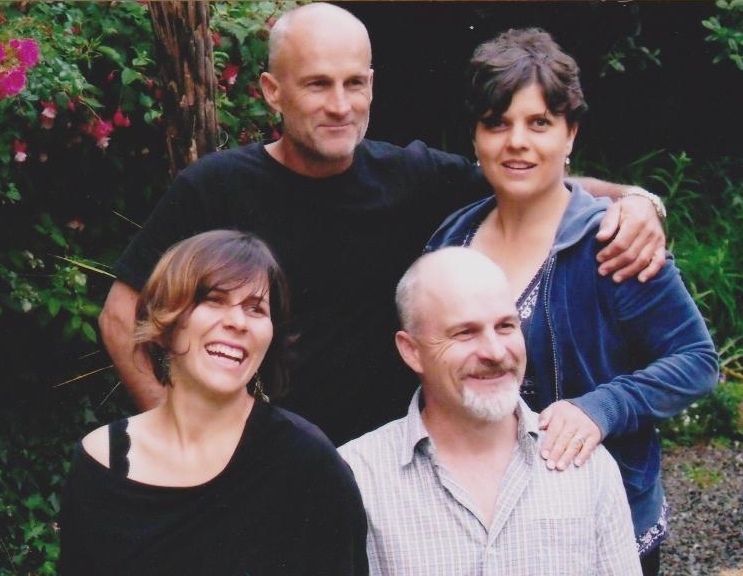

Joe’s English wife, Heather (née Lippross), arrived in New Zealand in 1958, aged 14. They met at a dance and married in 1960 when Heather was 17 and Joe 23. They had five children, twins David and John (born in 1962), Juliet (born in 1966 and died aged one month), Jane (born in 1970) and Suzanne (born in 1972). Now they have 14 grandchildren and eight great-grandchildren.

Twins David (top) and John Gratkowski and their sisters Jane Ralston (left) and Suzanne Caulton, taken on the same day as the photograph below.

With Jane living in London and the Suzanne in Dunedin, Joe and Heather cherish their family gatherings, the last complete one in 2010. Heather is standing second from right. Joe, front left, is next to Heather's mother, Avis Lippross, who became Joe's “surrogate mother” and sole grandparent to their children after her husband, Frederick, died in 1973 when Suzanne was six months’. Avis died in 2014 aged 94.

Heather describes Joe as a loving and caring husband and father. His family bestows a gentleness that conceals the hard core Joe admits moulded him as a child.

“My wife sometimes will say, ‘You can be a hard man at times.’ I say, ‘I had to be hard, to survive.’

“We were survivors.”

© Barbara Scrivens, 2018

Updated May 2019

ALL PHOTOGRAPHS, EXCEPT THE FIRST BY BARBARA SCRIVENS, FROM THE GRATKOWSKI COLLECTION.

THANKS TO THE NORTH AUCKLAND RESEARCH CENTRE IN THE TAKAPUNA LIBRARY FOR THE LOAN OF AUDIO RECORDING EQUIPMENT.

ENDNOTES:

- 1 - Stanisław Gratkowski’s grandson, Cameron Bourgeois, found the records while he was researching the family story. If anyone would like to contact Cameron, please let us know through the Get In Touch page.

- 2 - Map from MapyWIG, this particular one from

http://maps.mapywig.org/m/WIG_maps/series/100K_300dpi/P51_S42_SKALAT_300dpi.jpg - 3 - This page is part of the Sikorski Museum and Polish Institute’s website, http://www.pism.co.uk/.

The siblings appear on page 17 of the document KOL:138/297 LISTA EWAKUOWANYCH Z ZSSR RODZIN POLSKICH W CIĄGU SIERPNIA 1942r, LITERA F-M, NAKŁADEM “WIEŚCI POLSKICH” - 4 - Isfahan city of Polish Children, 1989, page 494, Association of Former Pupils of Polish schools, Isfahan and Lebanon. Editors, Irena Beaupré-Stankiewicz, Danuta Waszczuk-Kamieniecka and Jadwiga Lewicka-Howells, OBE, ISBN 0 9512550 1 2.

- 5 - Ibid, excerpt from the Red Cross list.

- 6 - http://www.polishresettlementcampsintheuk.co.uk/passengerlist/georgic1948.htm

- 7 - Thanks to the volunteers at the New Zealand Society of Genealogist’s Family Research centre in Panmure,

Auckland, for guiding me to the Rangitane passenger list.

https://www.genealogy.org.nz/