Kazimierz (Kazik) Zając

Tess Campbell asked her eight-year-old visitor, Kazik Zając, the question most children dread: “And what do you want to be when you grow up?”

Kazik did not hesitate:

“I want to be a pilot (which he pronounced the Polish way, pee-lot).”

“And why do you want to be a pilot? (repeating Kazik’s pronunciation)”

“I want to fly over Poland and drop bread.” In 1946, Kazik had heard of food shortages in his birth-country.

Years later, Mrs Campbell reminded Kazik of their conversation and his prophetic words:

“I was aerial top dressing, and it’s a bit like that: You help make the wheat grow.”

Kazik knows how fortunate he was to have been embraced by John and Tess Campbell and their family of five. School holidays—that always seemed far too short—at their Whanganui farm turned into a more permanent place to stay when, at 16, he was given ₤40, told he had to leave school, and make his own way in the world.

The Campbells tapped into the core of Kazik’s personality—a dogged persistence to pursue his dreams and, later, his Polish identity.

In 1994, Kazik visited Poland for the first time since Soviet soldiers forced him, his mother and his baby brother to leave in 1940.

I thank Kazik and his wife, Jan, for taking the time to tell me about his earliest memories, his arrival in New Zealand as a six-year-old, his life as an orphan, and finding those dreams and his Polish core.

Here they are at their home near Kaiapoi with the light of their lives, their granddaughter, Lucy.1

—Barbara Scrivens

RECOGNISING NORMALITY

by Barbara Scrivens

Widow Meder was known in the neighbourhood for wielding a broom to keep unwanted suitors from her six daughters. She chased many from her farm on the outskirts of Lubaczów in eastern Poland.

Her fifth daughter, Bronisława, did not mind. She did not reciprocate the feelings of her numerous admirers and was determined not to marry a local man.

Józef Zając was different. He had had several jobs—including one as a chemist and another as a factory supervisor—but it was as a travelling postal official that, in 1936, he happened to overnight in Ostrowiec, close to the Meder farm, and happened to meet Bronisława, who decided he was the man she would marry.

Her mother had no more appreciation for Józef than she had for any of the other local suitors pursuing her girls. He travelled and—worse—he would take her away to the other side of Poland, where he lived. Widow Meder had already ‘lost’ two daughters to France.

Bronisława told her mother, “I will never forgive you if you don’t let me marry him.”

Her mother replied, “If you marry him, you will never forgive yourself.”

Bronisława’s and Józef Zając’s engagement photograph, taken at the Meder family home in Lubaczów. Bronisława is sitting and Józef is next to her in the light suit. Standing from left are an unnamed cousin, Bronisława’s younger sister, Maria, and her husband, Józef.

Bronisława Meder, 23, and Józef Zając, 27, married in the Lubaczów Catholic Church on 27 December 1936. The cold forced Bronisława to wear a coat over her wedding dress. Her mother cried throughout the service but later reconciled herself to her daughter’s choice of husband.

Maria (née Chady) Meder knew about marrying someone from outside her neighbourhood. Her husband had been Michael, an Austrian. He died, aged 42, of something so infectious that he was not allowed to be buried in the Lubaczów cemetery.2 Bronisława had been four and Maria, two.

Newly married Bronisława and Józef lived at the Meder farm for nearly a year but did move west to Józef’s home town, Chorzów, in Upper Silesia (Śląsk). Kazimierz Zając was born there on 24 December 1937 and his brother, Stanisław, in early 1939.

Kazik’s aunt Maria, here on the right, gave him this photograph, of his parents visiting her in Raciborz in 1937.

Bronisława, no doubt a dutiful daughter and devoted to her mother, wanted to mend any rift between her and her husband. She brought Józef and their new son, Kazik, to spend the 1938 summer holidays in Lubaczów. She arrived again, on 15 August 1939, without Józef but with a second son to introduce to Maria Meder.

Maria Meder surrounded by family in the summer of 1938. Sitting left of her mother is Bronisława; on her right is eldest daughter, Julia, who married Julian Pietrasiewicz (standing between his wife and mother-in-law). Paulina, who had married Wincenty Brzeziński (standing behind her), sits with her daughter Stasia on her lap. Stasia’s sister, Teresia, is sitting between her cousins in the front. Bronisława’s younger sister, Maria, is on the grass with the children. The boy on the left of Teresia is Józef Pietrasiewicz and to the right is his brother, Władysław. Józef Zając took the photograph.

Nazi Germany invaded Poland two weeks later. While Polish troops fended them off, from 17 September, Soviet Russia started to overrun the largely unprotected eastern Poland. The occupying Germans and Soviets consolidated their Treaty of Friendship—first signed on 23 August 1939—by physically dividing Poland on 28 September 1939, and leaving Bronisława trapped behind Russian lines.

Paulina’s husband, Wincenty Brzeziński, wrote to Kazik in 1960: “Later [1939] a regulation came out, that whoever had family outside the border, that means where your father lived, they can register and return.

“Your mother registered to go back to your father. In the meantime, it was not true, not allowed, and you found yourselves in the territory of the USSR.”3

Kazik: “Her family told her not to register. Only people ‘out of district’ had to register. She was born there and was visiting her family, but she wanted to get back to my father. The Russians said she was a German spy, deported us and left the rest of the family.”

His aunt Maria gave Kazik this photograph of himself in Chorzów, near Katowice, aged about 18 months.

It is not clear how much time elapsed from when Bronisława gave her name to the Soviet occupiers and when 12 Russian soldiers with guns that “covered every door and window” forced her and her sons from her mother’s house, and told her they were bound for Siberia. The family pleaded in vain with the soldiers to allow Bronisława to leave her infant sons behind.

Kazik: “We were taken to the station and 12 hours later, we were still there as the train was being filled up.”

Wincenty, in his letter: “You were with us on 29 June 1940…

“Your mother didn’t have anything to change you into for the journey. I gave your mother a bit of money, some clothes from our children, coats and shoes, an eiderdown and blankets… and your little brother died because on the way there he got so cold, he became ill and died.”

A former cattle train, fitted with rows of planks against the walls for its human cargo, left the Lubaczów railway station on 30 June 1940,4 destined for Gordiejewo, in Altai Kraj, on the north-east Kazakhastani border with southern Russia. At least two other mass transports of Polish civilians had arrived in Gordiejewo a few months earlier. Those two trains left on 1 February 1940 from Dereniów and Monasterzyska, both closer to the then Polish-USSR border than Lubaczów.5 The Lubaczów train brought the number of Poles incarcerated in the NKVD forced-labour facility near Gordiejewo to 4,210.

Wincenty clearly did not know exactly what happened to Stanisław because in that first letter, he also said, “Every month we sent a parcel of food so that you could live because your mother could not work because you were both so small.”

This led Kazik to believe his baby brother may have survived the train journey, but not for long. Two very young children to look after would have prevented his mother from being able to work immediately, and not working reduced her to minimal rations—usually a slice of dark, heavy bread a day—that she had to share with Kazik, then two and a half, and 18-month-old Stanisław.

Kazik’s cousins, Teresia and Stasia, told him that a Jewish traveller known to the family, carried their letters and parcels, but it is unclear how many of those parcels reached Bronisława in heavily populated Gordiejewo.

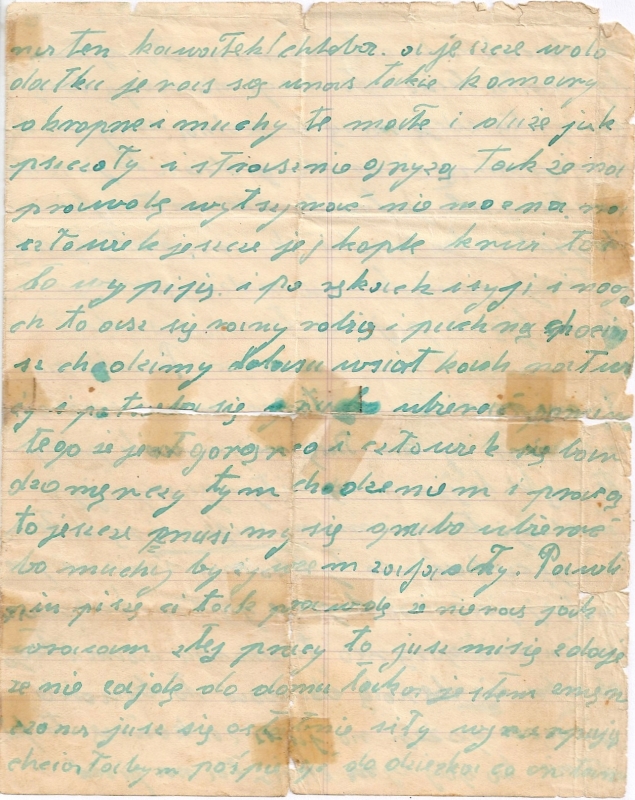

Bronisława wrote her final letter to Paulina on 9 June. The corner, where the year would have gone, is torn but must have been 1941.6 Her translated words:

“I am very happy to have found out that you have also sent two parcels, but at this point I have not received them. As soon as I receive I will write to you. Pauline, you write and ask about our health, well it is not good…

“Lately we go collecting resin. I am paid about 10 kopjejek per kilo, and you can collect about 10 kilogrammes, sometimes 15 or 20, but one needs to get up early, and I cannot go earlier because of Kazik because he would like to sleep longer and I keep having to drag him from the bed because I have to go to work and he hasn’t had enough sleep, cries, grumbles and wants to come with me, and I have to walk far, three or four kilometres one way. By the time I get there, it soon is time to go home for dinner.

“Dinner, what dinner, because I could just take that tiny piece of bread with me but I have to see what Kazik is doing because I left him without anyone to care for him because there is no one to leave him with. The Bureks, I don’t want to bother them because for free is not quite right and if I were to pay them, then what with, I cannot even earn enough for bread. I have already been forced to borrow 25 roubles and they are running out, and then I don’t know what I’ll do because there is nowhere to borrow from again, because now everyone is without a penny and if this lasts much longer people will be dying of hunger, because even if one can borrow once or twice, they will later die from hunger because no one can earn enough for that piece of bread.

“And in addition, we have here these monstrous mosquitoes and flies like bees and they bite so terribly that it is almost too hard to bear. If a person has a drop of blood they will drink it, and on arms, neck and legs they make wounds that swell. We go into the forest with nets on our faces and need to dress heavily despite the fact that it is hot and a person tires so much, we have to wear heavy clothing or we would be eaten alive.

“Pauline, I tell you truthfully that there have been times when I return from this work and wonder whether I will get home because I am so tired I am using the last of my strength. I would like to hurry home to my child to see what the poor thing is doing, and I do not have the strength. My head wants to fly but my legs cannot because they are so heavy it seems as if each one weighs 100 kilogrammes and it seems to me that the next day I will not get up. And yet I have to carry on with this torment because I have to earn enough for at least a small spoon of watery barley in Lenten water, because if it doesn’t get better soon (illegible) wake up, ‘ot nado rabotać.’ [in Russian, ‘I need to work.’]

“Pauline, you comfort me (illegible) I don’t know if God will allow me to live through this torture because my strength is running out and I also have no hope. I think that now I can wait only for death, rather than for a better tomorrow. Because although the heat is coming, they won’t again be giving us us that bread and it will be even worse. Now, I have to finish this writing, because if I wanted to write… (ends abruptly).”

The last pages of Bronisława’s final letter to her sister Paulina.

_______________

Jan Zając took this photograph of Kazik, below the Lubaczów railway station sign in 1994, in exactly the same place he stood with his mother and younger brother in 1940.

Even though he was only two and a half years old at the time, Kazik absorbed enduring memories of saying goodbye to his aunt Paulina and her daughters at the railway station. He remembers exactly where he stood on the platform, and has never forgotten how his aunt Paulina took a doll from Teresia’s arms and gave it to him—nor the “very sour look” that his cousin returned.

“What I was going to do with a doll, I don’t know. It was a sympathy gesture by Paulina watching the Russians deporting her sister, yet leaving her alone.”

Kazik has no recollection of the fate of that doll, or the subsequent more than 4,500-kilometre train journey, which would have taken at least three weeks.

Kazik’s only memory of the NKVD forced-labour facility resulted from his mother’s distraught reaction to his absence when she arrived to pick him up from his babysitters and could not find him.

“They were a peasant family with a house. I wandered outside the compound and ended up near the water. She gave me a frantic bollocking.”

Stalin granted an ‘amnesty’7 to the Poles on 30 July 1941 (For more details, see military timeline), and allowed them to leave his forced-labour facilities in order that they form a new Polish army and fight German troops, which two weeks earlier were only 320 kilometres from Moscow.8

It is not clear exactly when the Polish exodus from Gordiejewo started, but it took far longer than the train journey more than a year earlier. Even if the Soviet trains stopped at stations, any Poles able to get on them soon became displaced by Soviet soldiers and ordnance going to the front.

Kazik believes his mother died of septicaemia, caused by the infected insect wounds she told Paulina about in her letter.

“There were many stops and many trains. During one of the stops, I clearly remember her in a bed, dying. Although I didn’t fully understand at the time, I knew at once that I would never see her again; that she had died.

“There was a group of us and someone told me a man called Bąk took care of me for a while.”

Someone else took Kazik to one of the Polish orphanages that opened in Uzbekistan near a Polish army enlistment station and provided his and his mother’s correct names. Neither appears on the Red Cross list of Polish evacuees who escaped the USSR via the Caspian Sea. Kazik’s memories of being at the back of a truck with other children and travelling over the mountains, makes it likely that his route out of the USSR took him via Ashgabat in Turkmenistan, to Mashhad in then Persia (now Iran). Next was a “tent village” in Teheran.

From Persia, Polish men and women joined units of the Polish Army and British Air Force, and took part in some pivotal European battles.9 Polish teenagers who had joined the junaki, the Polish army’s cadet wing set up to educate and guide them, moved to sites in Palestine and Egypt. Polish men not eligible for the army and women with children were settled in refugee camps in east and southern Africa, Mexico and India.

Kazik became one of the more than 2,000 Polish children younger than 14 who lived in Isfahan between 1942 and 1945.

To him, his life held no sense of abnormality.

“I was so young that didn’t matter what happened, this is the way the world was. Everything was normal to me. I didn’t know anything else.

“The villas we were put up in, I think, belonged to the Shah of Persia and some of them had magnificent gardens on perhaps an acre of land, with a well in the middle, buildings on either side, and very high clay walls and huge gates to keep out thieves. The walls would have been at least three metres tall and quite thick. They looked enormous to me.

“We were taken for walks in the town and countryside, cemeteries and to the church, an Armenian church—Ormian, we used to call them.

“Some of these villas in Persia had walled gardens. They were beautiful and the scents in the enclosed gardens with the high walls and hot temperatures were just out of this world. They have stayed with me all my life. I remember most vividly the roses—I still can’t go past a rose without sniffing it—and the deep blue cornflowers and the pansies.

“At that time I didn’t think of the future. I’d not got over the fact that my mother was gone, but I accepted it, maybe because we were such a big group, all of our separate lives were diluted into this big family.

“One day, people ran into our house saying, ‘The bishop’s coming. You have to meet the bishop.’

“The bishop came. There was a group in the foyer and I went halfway up the stairs to see better what was happening—I was about four and a half. The bishop said, ‘What would you little boys like?’ They had been schooled to say they wanted prayer books and things like that. I put my hand up and said I wanted an aeroplane. I remember that vividly. So it was even then.”

The dream to be a pilot did not come from any knowledge of the 303 Polish Fighter Squadrons’ bravery and prowess during the 1940 Battle of Britain, nor from the other 15 Polish squadrons that fought for the Royal Air Force during WW2, nor from any stories about the war still raging: it was simply there.

“I’ve thought about it a lot, and know that the only place I could have seen an aeroplane was over Lubaczów, when the Russians invaded.10

“I didn’t know anything about the Polish army, then, or in Pahiatua, as in Persia, each individual child had their own thoughts and experiences, which they rarely shared. The Pahiatua camp was divided in half, girls here, boys there. I knew boys for nine years and I never knew they had a sister in the camp. To my knowledge, they didn’t fraternise with them.”

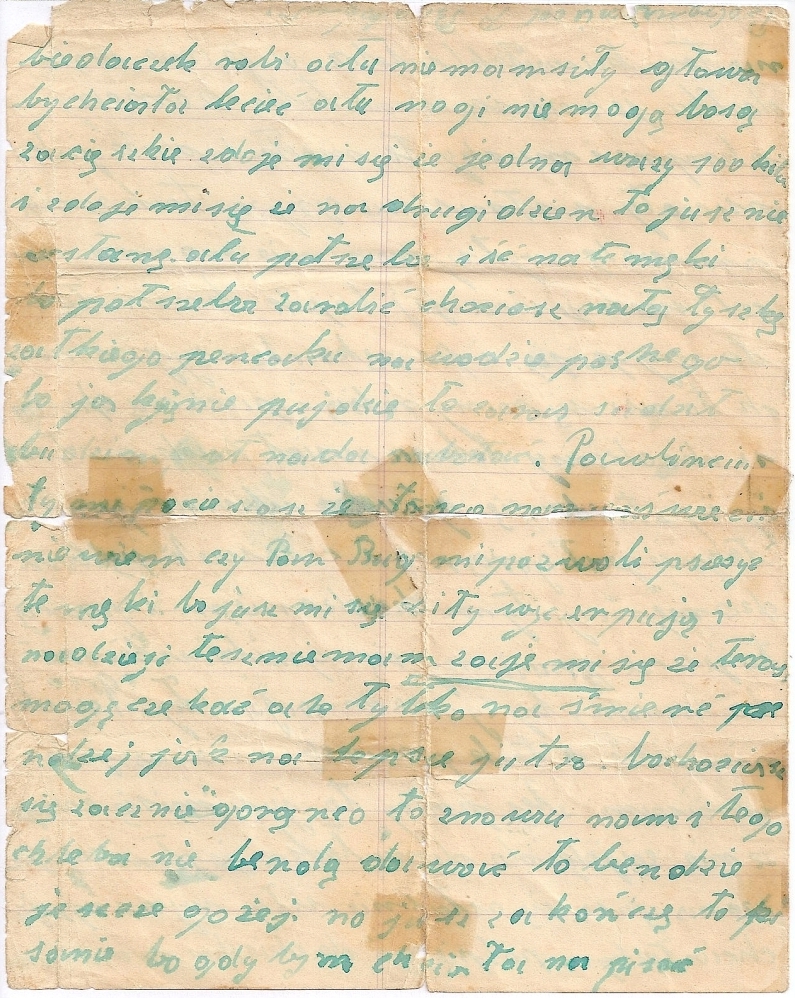

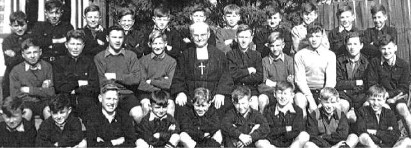

The youngest boys at Pahiatua with their housemistress, Mrs Maria Petrus. Kazik is in

the front, third from the right.

Other boys he remembers are: Back row, from left: Franciszek Barański (third), Waldemar Dejnakowski (fourth), Ryszard

Patulski (fifth) and Zygmunt Dutkiewicz (third from right);

Middle row, from left: Zdzisław Iwan (far left), Bogusław Turski (third), Henryk Apanowicz (fourth), Mrs Petrus’ son, Michał,

(fifth), Marian Sadowski (sixth), Kazimierz Krawczyk (seventh) and Tadeusz Piotr Sapinski on the far right.

Front row: Lech Dubronski (second from left), Jerzy Juchniowicz (right of Kazik) and Zdzisław Lepionka (far right).

Kazik has fond memories of Mrs Petrus, a “motherly person loved by all the boys.”

“In Pahiatua, we had the most wonderful life, the freedom to do anything we liked.

“There was one time when we started making our own guns out of match-tops. In those days they had wax matches, which were used for roll-your-own cigarettes. When you lit the match, the wax started to melt and you could rub the wax on the end of the cigarette so it wouldn’t go soggy. The heads from those matches, zapałki, made very good gunpowder. We made guns out of copper pipe, like old-fashioned cannons but in miniature.

“One boy made one of these guns, and was leaning on the rod, against the building, compressing the gunpowder, which went off. The rod went almost through his stomach and they rushed him to the camp hospital. There was a big commotion, and they confiscated all our matches and pipes—those they could find.

“We came across a chemical that, when you mixed it with water, released an enormous amount of gas. You got a jar, put in some of the chemical, added some water, closed the lid, and threw it out onto the water, where it exploded. The trout got stunned and came to the surface, and the local ranger (a camp staffer and a keen fisherman) would confiscate them, to take home to eat, I guess.

“What we couldn’t make out of rudimentary materials, was unbelievable. Now it’s ‘go and buy.’ We were inquisitive and totally resourceful. You don’t get that now.

“In hindsight, sure, there was discipline, but the life was unreal, fabulous.”

The younger boys in the Pahiatua camp dining room. Kazik is at the end of the second table from the foreground, looking towards the cameraman.11

“In the early days of the Pahiatua camp, we had to be documented. I got called into the camp administration office and was asked, ‘When is your birthday?’ I replied that I didn’t know. They said, ‘Today’s the 19th of March. That’s your birthday and you are seven years old.’

“All my life I wondered, ‘When was I born? Where was I born? What was my father’s name? Is my name my real name?’

“If you’re called by a name all your life you assume that’s your name, but what if it isn’t?

“The adults who looked after me in Siberia would have known my mother, and a little bit of her history. The problem was, in New Zealand, they made up my mother’s maiden name. The adults [in the USSR] would have known she was Bronia, Bronisława, but they would not have known her maiden name. The authorities in Pahiatua, would have known her as Zając, married with a child, so they gave her a really Polish maiden name, ending in –ski. They had to have records but that made it extremely difficult to find out what my origins were.”

Kazik has an undated governmental IA-91 form: Application for Registration of a Minor as a Citizen, which shows his father as Władysław Zając and his mother as Bronisława Zając, née Szczepinska. He had no reason to doubt its accuracy.

Kazik, aged about eight, holding the Pahiatua camp’s canteen cat.

“When I was in Pahiatua, the woman who looked after our dormitory unwittingly told me that an uncle was looking for me through the Red Cross, but that the New Zealand government and camp authorities said I wasn’t going back. It was too dangerous in Poland because it was a communist country: ‘You can stay here until you’re old enough to make up your own mind.’ They made up our minds for us, and it was a good thing.

“My mother’s family tried to find me a second time. By then, the camp had closed. I was about 23 or 24 and living in Christchurch attending an airline course for NAC.12

“Aunt Paulina wrote to me through the Red Cross, and I started to correspond with her and the family. I extracted information about myself and my mother, and found out that she was a Meder. It all began to make sense: my New Zealand records were wrong.

“I eventually got my Polish birth certificate. I was born on 24 December 1937, so the camp officials weren’t far out.

“There was a lot of inventing information in Pahiatua: you can’t live in a country without some sort of documentation. When I found out my real birthday, I rang Internal Affairs in Wellington. They implied that they didn’t want to know: what their records showed was going to be my official date of birth. Now I have to think which birthday I give to people. I say, ‘I’ve got two, which one do you want, the legal or the actual?’ ”

_______________

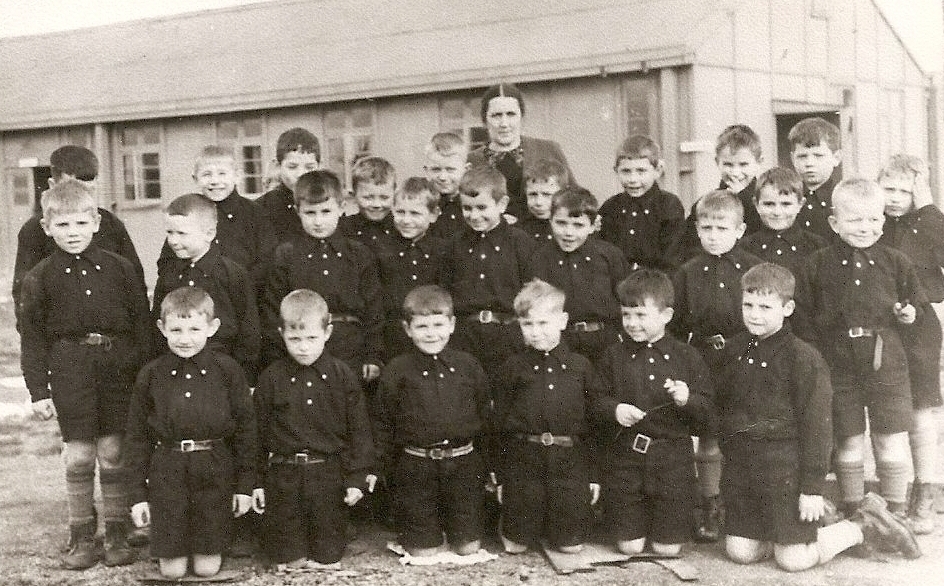

“During the holidays, we were farmed out all around the country to Kiwi families, to give us a break from camp. The Catholic Church asked New Zealand Catholics if they would be prepared to take some of us. I went to the Campbells. They took me every holiday, and more or less adopted me.”

Kazik holding Grey, one of the Campbell’s draught horses, during a holiday at their Whanganui farm, Cherrybank, in May 1946. The rolled-up trousers were a typical Pahiatua camp issue. In front of the fence, on the right-hand side is a pram with the Campbell’s first child, Naomi, who was six months old during Kazik's first visit.

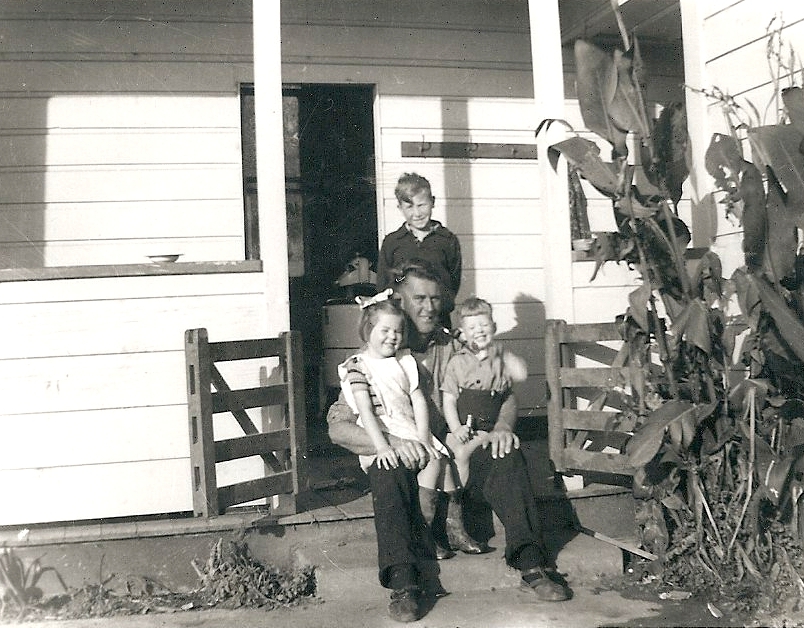

Kazik on holiday at the Campbell’s farm in 1949. John Campbell has his daughter, Naomi, and son, Donald, on his lap. The Campbells later had three more children.

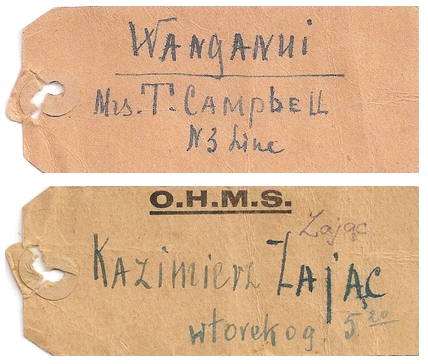

“On our first visit to Kiwi families, we were put on the train with our suitcases and labels around our necks. When we arrived at the station, we lined up, and the host families looked at the labels, to see which parcel was for them.

“I was the parcel for the Campbells, and stayed there every subsequent holiday. At one stage, the Pahiatua officials decided I needed a friend, so they invited Zdziszek Lepionka, who joined me once or twice.”

Tess Campbell kept this label as a memento of Kazik’s first holiday with them. When Kazik left the farm to go aerial top dressing in Taihape in 1960, she told him, “I’ve got something for you…”

“Pahiatua closed through attrition as the older children left. There were about 40 of the youngest boys left—enough to carry on under Polish guidance—so they built us a hostel in Hawera.”

The accommodation earmarked for the boys was the former stately family home built 40 years earlier for wealthy dairy farmer, and later Member of Parliament, Walter Dutton Powdrell.13 While the Department of Social Welfare added dormitories to the home, the boys lived briefly at the Linton military camp and attended the Marist Brothers Primary School in Palmerston North.

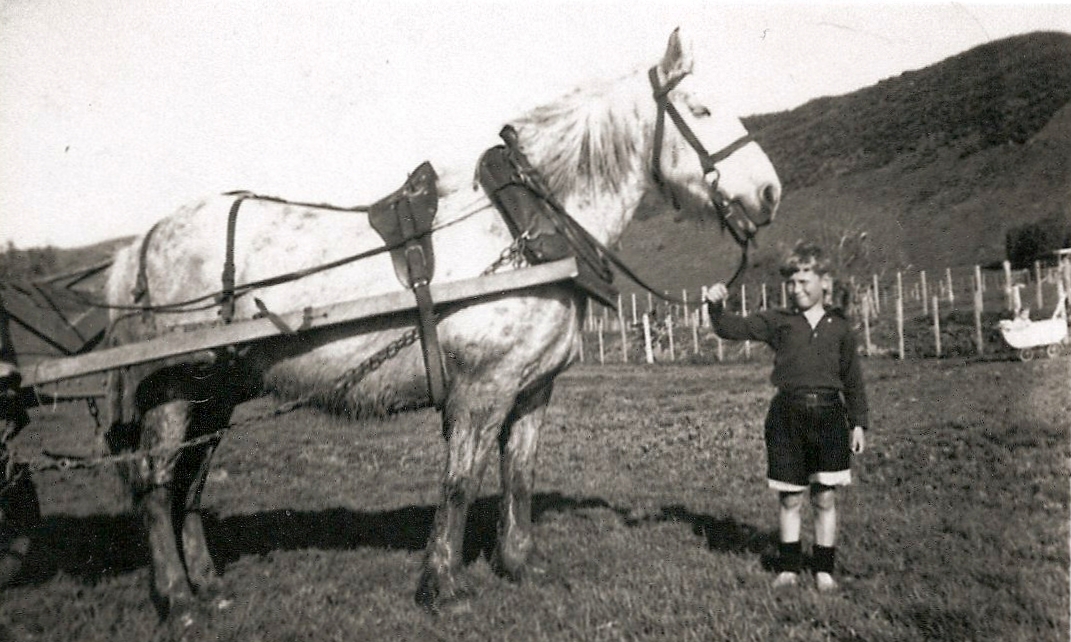

Some of the youngest boys from Pahiatua who temporarily attended Marist Brothers Primary

School, Palmerston North, in 1949.

From left to right, back row: Marian Sadowski, Krzysztof Dziegieć, Józef Jagiełło, Ludwik Głogowski, Kazimierz Krawczyk,

Zdzisław Lepionka, Zdzisław Iwan, Bogusław Turski, Antoni Sarniak, Leon Zyzało, Tadeusz Rozwadowski;

Middle row: Jan Makuch, Franciszek Barański, Kazimierz Niedźwiecki, Antoni Rybiński, Brother Egbert, Zbigniew Dziki,

Bronisław Gmyterko, Stanisław Zyzało, Bogdan Bocian, Tadeusz Najbert;

Front row: Waldemar Dejnakowski, Jerzy Juchnowicz, Tadeusz Jankiewicz, Bronisław Węgrzyn, Lech Dobroński, Kazimierz Zając,

Witold Pleciak, Eugeniusz Sarnecki, Henryk Apanowicz.14

The boys at the Hawera Hostel with their care-givers, Mr and Mrs Tietze. Jadwiga Tietze arrived in New Zealand with her son, Tadeusz, and the other Pahiatua children and care-givers in November 1944. Her husband, Roman, joined them after the war. The priest is Father Broel-Plater, who replaced Father Wilniewczyc. Kazik is on the far left of the front standing row.

Kazik continued to spend holidays at the Campbells. Years later, Tess Campbell reminded him of how frantic he became about losing one of his handkerchiefs.

“Discipline at Hawera was severe at times. When we went on holiday, we packed our own bags, and had to come back with everything. I was a hanky missing, and to me that was a monumental problem.

“I was really worried about what would happen if I got back to the hostel without the hanky, and anticipated a hiding.”

Mrs Campbell’s offer of one of the family handkerchiefs was not good enough—Kazik knew the Tietzes would recognise it.

“In the end, no one missed the hanky, but it completely spoilt my holiday.”

Kazik’s first taste of English immersive education came at Hawera Convent School, which brought out Sister Charles Vickers15 from retirement. She had a reputation for teaching English.

“She anglicised some of our names and, because Kazimierz was a saint translated in English to Casimir, they called me Casimir.”

Sister Charles organised lawn-mowing jobs for the Polish boys after school, and the Church paying 2/6d to sweep the building before school on Fridays was all the incentive Kazik needed to get up extra early.

Kazik, aged 11, took his first flight over Normanby in a Tiger Moth.

“Other boys saved up quickly for bikes but I just wanted to fly. Ten minutes in the air was all I could afford. The open cockpit made me feel like a bird, freed from everyday worries and cares.

“I eventually saved up £2 for an old bike and wheeled it back to the hostel. The wheel rims were so rusty that I couldn’t ride it but Mr Tietze came to my rescue and fixed it using pieces of cut up jam tins on the inside of the rims to secure the spokes. I loved that bike and had it virtually the whole time I lived at the hostel. As I could afford it, I embellished it with double headlights and double dynamos. I often rode it holding a stick against the spokes, pretending I was riding a motorbike.”

At Hawera High School a year later, Kazik’s form teacher, Mr Shorty McPhail, decided his name was, ‘Too hard. We’ll call you Bill.’

“There was another Kazimierz in the hostel. He was given the name Bernard. The nuns tried harder.

“There wasn’t much schooling, really, because the hostel closed in 1954 and they more or less said, ‘Here’s ₤40. Go and find your own way.’ I turned 16 that summer.

“We weren’t thrown out with the ₤40. Mrs Tietze—she was kind and fair to us—took me to the local drapers and bought ₤40-worth of clothing.”

Kazik with the Campbells in 1956. Naomi and Donald’s siblings are Adrienne, Christopher and Felicity on Tess’s knee.

The Campbells had anticipated that the Hawera orphanage would close for the same reason the Pahiatua camp closed—declining student numbers. They expected Kazik to live with them, and had already arranged a job for him at the local garage.

“I was a very mechanically minded as a kid and I thought I’d be a motor mechanic. Half way through the course I realised it wasn’t for me: I wanted to join the Air Force, so I went to see the Labour Office about it.

“ ‘You can’t because you’re an alien.’

“ ‘Well, when can I join?’

“ ‘When you’re naturalised.’

“ ‘When can I do that?’

“ ‘When you’re 21.’

“That was when I applied to the Polish authorities [in New Zealand] for my papers and saw the incorrect names given to my parents [on the IA-91 form].

“What the Labour Office told me was wrong, because I could have been naturalised at any time, provided I met the criteria, but by the time I found out, it was too late: I was already locked into a motor mechanics apprenticeship for four and a half years.

“In hindsight, it was to my advantage as I have been able to indulge in mechanical and engineering hobbies throughout my life.”

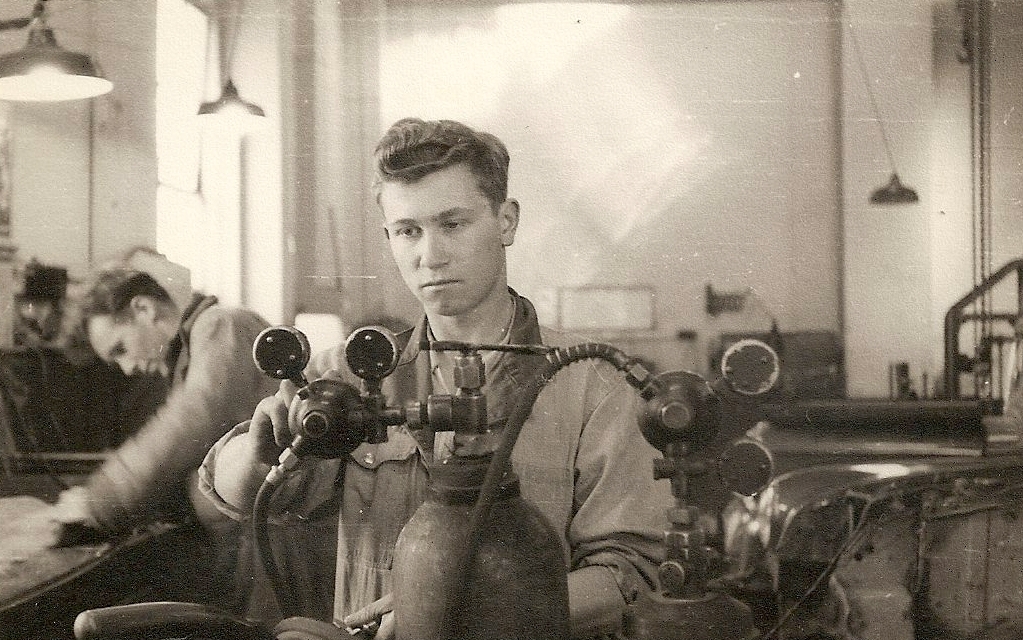

Kazik photographed in a motor mechanic’s apprenticeship workshop in 1957.

The Department of Labour sent Kazik a congratulatory letter for winning top place in New Zealand for motor mechanics.

RG Hawke, District Commissioner of Apprenticeship: “To have gained 1st equal in New Zealand for your 1st Qualifying Examinations in 1955 and to follow it with your recent success is indeed a marvellous effort. Your parents and employers must feel very proud of you.”

The Campbells were proud and John went with Kazik to the prize-giving, where he received a Parker 51 pen, which he still has and uses, and more practically, tools, “A godsend because I could then spend my money on flying lessons.”

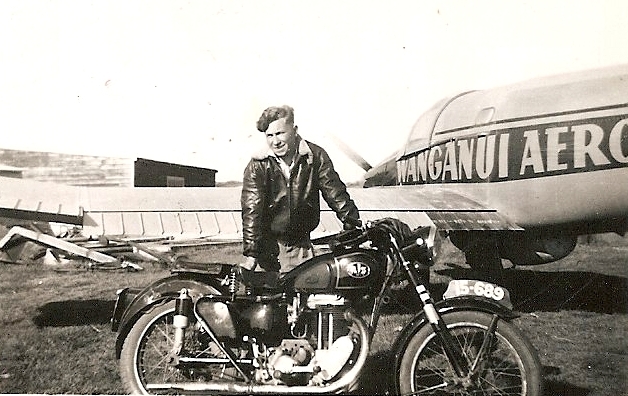

A year after Kazik’s schooling abruptly ended in 1954, he owned his first motorbike and relished the freedom it gave him.

“Motorbike mad” Kazik with Jan Muller and his Model A Ford. Originally from the Netherlands, Jan worked on the Campbell farm for many years and shared a sleepout with Kazik.

Kazik finished the apprenticeship and immediately applied to be naturalised. In April 1959 he received a letter informing him that he had been “removed from the Aliens Register.” He had to surrender his then-cancelled Aliens Certificate no. 59111, which he had received from the Hawera orphanage when he left, and which Aliens in New Zealand older than 16 had to carry “at all times.” (The certificate and its rules is shown in full in Janina Iwanica’s story on this page, under displaced persons.)

Kazik: “As I progressed through my apprenticeship and got a little bit of spare money, I learnt to fly privately at the Whanganui Aero club. When I finished the apprenticeship, I was half-way towards my commercial pilot’s licence. I passed the theory exams and course, but I didn’t have enough flying hours to get the actual licence. I ran out of money.

“I am eternally grateful to John Campbell, who lent me the ₤200 I needed to complete the licence. I went aerial top dressing and nearly killed myself so many times, I thought, ‘I’m not going to last long in this job.’

“I wrote off one top dressing plane in Taihape: the farmer decided he wanted the job done despite the wind, so he tied the windsock to the post. I assumed it was calm but halfway through my approach to land, I realised I had a very strong tail wind. It was a one-way strip, so a go-around was not possible. I was committed to land knowing that I would not be able to stop because of high speed and wet grass. I ended up crashing into a loader tractor parked at the end of the strip.

“When I phoned my boss to advise him of my predicament, he said, ‘You young buggers don’t know how to fly. I’ll come and fly it out.’ He turned up at the site, looked at the heap of rubble, and then said, ‘Why didn’t you tell me it was that bad?’

“That night I wrote a letter to the national airline, NAC. They replied, saying that although they had no vacancies then, they would keep my application on file because I was young enough [21].

“The next week I received a telegram: ‘Present yourself for an interview.’ The next day they sent me airline tickets and I shot off to Wellington—my first time in a passenger plane. I was interviewed and accepted. I gave in my notice at the top dressing job, moved to Christchurch where the NAC training school was, and started training as an airline pilot.”

Ill-health forced John Campbell to give up the Cherrybank farm in 1977. He died in 1982 and Tess (Mary Theresa) died in 1998. They are buried together at the Aramoho Catholic Cemetery in Whanganui.

_______________

Jan (née Mulholland), born and brought up in Ranfurly, Central Otago, had also moved to Christchurch to follow a career at NAC. She gave up teaching to pursue an interest in travelling and meeting people from different countries and cultures.

Jan: “We flew together a few times and…”

Kazik: “I was an island all my life until I married Jan.”

Kazik and Jan Zając after their marriage at St Teresa of Lisieux Church, Riccarton, on 26 August 1970.

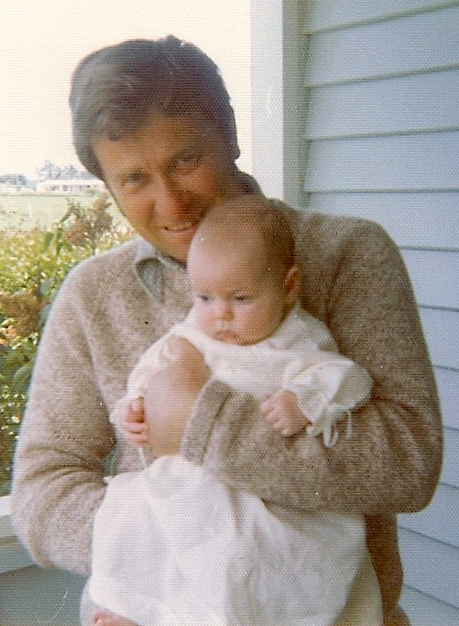

After they married, Kazik and Jan lived in Puriri Street, down the road from the church where they exchanged their vows. After Justin was born, they bought a rural property in Clarkville, north of Christchurch, where they had Rachel.

Kazik at his and Jan’s first rural property in Clarkville, north of Christchurch, with Justin, aged two, and Rachel, three months.

Memories of the Persian gardens and their sumptuous scents still drew Kazik, and when an empty 50 acres nearby became available, he and Jan bought it, built their home, and developed their own piece of garden paradise.

The large grounds are not quite the same as the Persian gardens of his memories—only 11 roses thanks to the lighter soil—but colour and perfumed flowers abound, the asparagus is bountiful, and the strawberries are enormous and juicy.

Above, the now mature trees anchor the constantly changing colour in the Zając garden.

Kazik's ride-on lawnmower makes keeping the grass under control a contemplative pleasure.

Left, Kazik at home in one of the latest additions to the garden, a path and patio created for Jan’s 70th birthday.

Kazik’s Persian experiences even eased themselves into his airline career:

“One of my vivid memories was the delicious halva in Persia. At an airline refresher course, we had a lecture on terrorism, and the instructor said that the terrorists hid explosives in halva tins because it looked the same. He said, ‘Anybody know what halva is?’ He was taken aback when I put my hand up.”

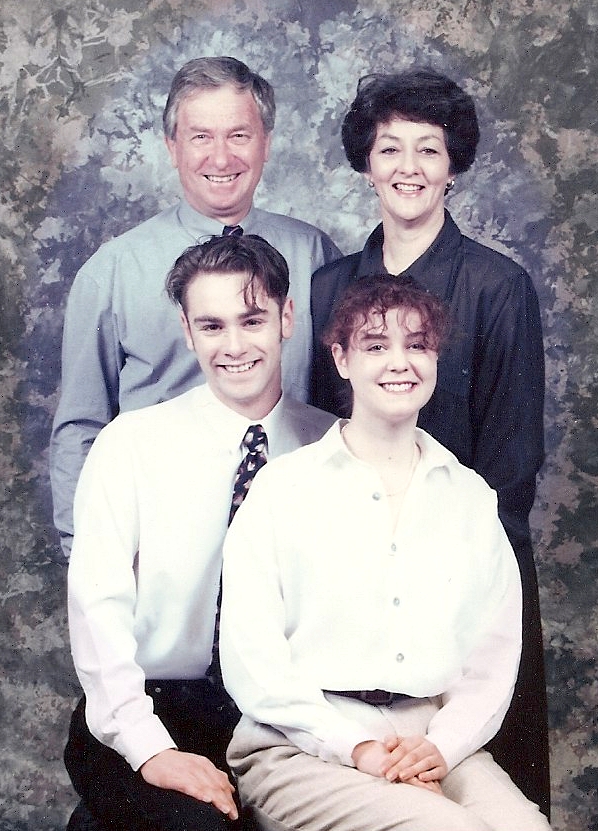

The Zając family in the late 1980s. Rachel is Lucy's mother.

_______________

In Pahiatua, after some of the other boys’ fathers arrived in New Zealand, Kazik tried—unsuccessfully—to trace his own. He fetched an aerogramme letter from the canteen and wrote to the Red Cross, but did not send the letter because he did not have the postage. An emphatic scolding from Mrs Petrus, when she found it in his bedside cabinet, was enough to dissuade him from pursuing that thought.

It is not clear why someone Kazik considered so motherly would reprimand him for wanting to find his father. Perhaps she knew that the Pahiatua administration had invented names on Kazik’s New Zealand documentation, and wanted to spare him the anguish of a search she knew would lead nowhere.

In late 1959, Kazik’s aunt Paulina in Lubaczów tried again to find him. Her letter reached Kazik at the Campbell farm. Then an adult, Kazik had no one to put him off initiating a dialogue with a stranger who said she was his mother’s sister. He replied.

Kazik’s maternal aunt Paulina Brzeziński plucking a chicken in her back yard in Lubaczów, Poland, in August 1976.

In his first letter, dated 18 February 1960, Paulina’s husband, Wincenty, wrote:

“Our dearest Kazik!

“Finally, after such a long search, we have found [recovered] you.

“We are so happy—and even more so that you are happy—that you have someone else in the world.”

(“Kochany naz Kaziu!

“Nareszcie po tak długim poszukiwaniu odnależlismy Ciebie.

“Bardzo się cieszymy—i tak jeszcze bardziej że i Ty się ucieszyłeś—że jeszcze kogoś masz na świecie.”)

Wincenty Brzeziński gave Kazik what he had asked for: details about his parents and himself. Most surprising were his parents’ correct names.

The new connection had a bittersweet undertone: as wonderful as it was for Kazik to discover kindred blood after so many years, his lapsed Polish language skills, and his mother’s family’s complete lack of English made communication difficult.

His Polish family wrote that they had prayed for him on every St Kazimierz’s feast day, and wondered about his fate. His uncle Wincenty worried that Kazik had become too much of an Englishman, urged him not to forget his Polish roots, nor his Catholic background, and to visit his homeland.

While it was gratifying to hear from his mother’s family, their letters forced Kazik to face the fact that his life was progressing markedly differently from anything he may have experienced if Soviet soldiers had not forced him from his home in 1940.

“I did not feel any family bond. I’d got to that stage without family, so being without one was normal. I thought, ‘What am I going to do about this new development in my life? There’s a lot I have to know about myself.”

Ten more letters from his uncle, aunt and cousins in Lubaczów, written between 1960 and 1963, brim with joy at finding him alive and happy. Kazik had one request—his birth certificate, which his aunt Maria organised from the Chorzów registrar, and which confirmed his identity. Most precious was his mother’s last letter to Paulina—the paper rubbed away in folds and corners but in his mother’s hand.

The letters between Lubaczów and first Whanganui, then Christchurch, petered out, the communication too difficult at that stage for the young man establishing his career with New Zealand’s national airline—and he faced a moral dilemma: Kazik had been writing in English and was mortified when he found out that Paulina’s monetarily stretched family had to pay for each translation.

“I wrote to the Red Cross shortly after I retired in 1991, asking about my father. I found out that he had died in 1972, and was buried in Frankfurt.

When Kazik says, “I just happened to stumble on this…” he omits to mention his painstaking dedication to unravelling truth from minute detail. He found out that in May 1942, Józef Zając registered himself as Joseph Zajonz and melted into German life.

“That was bold of him.”

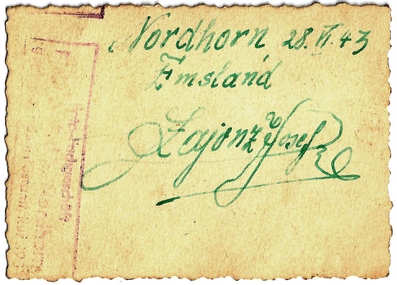

His aunt Maria gave Kazik this studio head-and-shoulder photograph of his father. The inscription shows his signature—clearly spelt Josef Zajonz.

The words above Josef Zajonz’s new signature, “Nordhorn 28.II.43 Emsland,” indicate that he had by then moved to the west German border with the Netherlands. Kazik approached the German Embassy in Wellington, and discovered the existence of his father’s second wife, Elsa, in Frankfurt.

Jan: “We found a telephone number in Frankfurt of a Mrs Zajonz, at the same address that we’d had from information we got from the German Embassy.

“A German friend, who lives nearby, conducted the initial phone call. Mrs Zajonz knew nothing of her husband’s previous life. She denied it all; possibly Józef had never told her.”

Kazik: “During the war, the most accurate description of Josef’s lifestyle is of a playboy, a real dandy. Look at the photographs: gloves, handkerchief in pocket, camera, motorbike, but not one photograph of him in uniform.”

“This photograph makes me think that Joseph came from a wealthy family. How many people had wireless sets before the war? And, judging by the looks he is getting, he was adored.” The older woman is probably Joseph’s mother, Maria, née Blachetzki, and at least two of the younger women are his sisters.

Fifty years after Kazik arrived in New Zealand, he met his half-brothers, Manfred and Norbert, in Frankfurt. Their sister, Brigitte, had died earlier. Uninterested in family history, they gave Kazik an unexpected gift—old papers and photographs, including a booklet that recorded four generations of their father’s family tree.

Kazik believes his father took advantage of the pre-WWI germanised spelling of his name, changed by the Prussians during the Polish partitioning of 1772-1918 (see polish anchors 1872–1876 in the early settlers page).

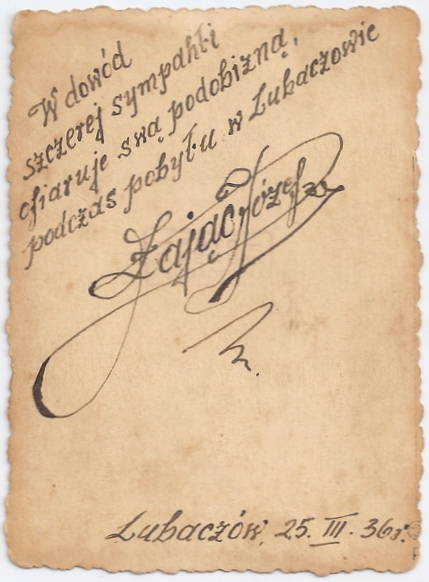

Germany’s defeat in WWI and the subsequent birth of the new Republic of Poland allowed Polish names to revert. The inscription on the photograph below leaves no doubt that the Polish Józef Zając, presented himself to Bronisława and her family in 1936.

Polish Józef inscribed and signed the back of this photograph in the Polish way—Lubaczów 25.III.36r, the “r” meaning year: “W dowód szczerej sympatii ofiaruję swą podobiznę podczas pobytu w Lubaczowie” (As a sign of sincere fondness, I offer my likeness during a stay in Lubaczów).

The family tree that Norbert gave Kazik shows the germanised names of several paternal ancestors born in then Prussian-partitioned Poland: His great-grandfathers on his father’s side were Franz Zajonz, born in 1856, and Peter Blachetzki, born in 1842.

Franz Zajonz’s wife was Maria Bednarek. His great-great grandmothers’ maiden names on the Zajonz side were Josefa Konietzko and Franziska Kandora.

Peter Blachetzki’s wife, Kazik’s other paternal great-grandmother, was Franziska Suchowski. Kazik’s great-great-grandmothers on that side were Josefa Brzezina and Franciska Glombitza.16

Kazik will never know exactly why his father moved to north-west Germany during the war. Józef may have surmised—but would not have had proof—that his wife and sons had died.

“He had three more children with his German wife, but his ancestry points to the fact that he was, in essence, a Pole. My birth certificate has his name in Polish. My name is Kazimierz and my brother’s, Stanisław. Would a father give his sons such Polish names if he weren’t Polish? He chose German names for his second family.

Manfred and Norbert had no idea of Kazik’s existence but Norbert may have guessed that his father had had a previous Polish connection, as he had asked Norbert to take letters and parcels to one of his paternal aunts in Poland.

“Norbert said that he never heard my father speak Polish and that he had such a ‘perfect’ German accent, no one would have known he was not German.”

_______________

Fifty years after arriving in New Zealand as an orphan refugee, Kazik returned to Poland with Jan.

In 1994, the country was still feeling the aftermath of post WW2 communist rule. Inflation was rampant. Warsaw streets were crammed with hawkers selling fruit, groceries, books, and crafts. Young people held signs saying they had AIDS and mingled with pregnant beggars and their hovering small children. As Kazik and Jan boarded their train for Rzeszów, three youths “created a fuss in the aisle” and extracted Kazik’s wallet from his back pocket.

Jan wrote at the time: “The taxi driver who took us to the station had told us to be on the look-out for thieves. Luckily we hadn’t changed all our money.”

“People are on the whole helpful if approached but otherwise keep to themselves and don’t look at you.”

Jan and Kazik spent a few days with Teresia and Stasia, who both still lived in Lubaczów.

“They confirmed the few memories I had of Lubaczów. One was of a man in the family home, in uniform and with a gun, which I was looking up at and very impressed with. The war had broken out, but it hadn’t heated up. I was very impressionable.

“My cousins thought he may have been their next-door neighbour, Michael Hass. They took us to a museum and showed me a photograph. The moment I saw it, I recognised him—a snippet of memory.”

Kazik knows his babcia Meder must have been the old woman “directing operations” when he developed a chest infection in the winter of 1939–1940 and made him lean, towel covering his head, over a steaming bucket of water infused with “stinky” herbs.

“She was strong and formidable and, according to my cousins, decided when she would die. She sewed herself a black dress, put it on, and went to bed. She said, ‘I’m not eating nor drinking. I’m going. Leave me alone.’ ”

She died five days later, aged 82. The year was 1953.

“I don’t think she committed suicide. She just decided she had had enough, said goodbye to her family, and went to bed to die. I think she couldn’t quite cope with post-war communism.”

_______________

Four of widow Meder’s daughters had left Lubaczów by the time Bronisława arrived for her 1939 holiday.

The two missing from the 1938 holiday photograph both lived in France. Second-born Elizabeth had worked in the French Consulate in Warsaw. When it closed, she accepted an offer to move to France, where she married and remained.

It is not clear why third-born Katarzyna went to France, but she married a widower with four children, had six of her own, and apparently received a French medal for being a “Mother of the Year.”

By 1939, Bronisława’s favourite sister, Maria, had married and moved to then Ratibor, now Raciborz, on the southwestern Polish-German border. The Nazis arrested her railways employee husband and sent him to the Dachau concentration camp. During his four years there, Maria lived with the family of a doctor who had also been taken to Dachau.

Weakened by his concentration camp experience, Maria’s husband, Józef, died before she was 50. He asked to be buried in Lubaczów, suggesting that in 1939, his railways job trapped him and Maria in Germany in the same way as Bronisława’s holiday trapped her and her sons behind the Russian cordon. His original ancestry was apparently from the southern Polish highlands, the górale.

Maria never remarried nor had children of her own but for years worked as a housekeeper for a dentist and his large family.

“Near her home, Aunt Maria had an allotment provided by the railways. After her husband’s death, she continued to receive two tonnes of coal a year from the railways, a railways flat at a reasonable rent, and subsidised rail travel. She had a wonderful garden and sold her excess produce. She was a fabulous cook and treated herself with herbs. The dentist wouldn’t let his wife cook for him as Maria’s food was so much better.”

Maria told Kazik and Jan that during the war in Raciborz, the Germans forbade the Poles to speak Polish; they had to learn German. Maria’s Austrian maiden name, meant she avoided being “sent out to work”—her euphemism for not being sent to a Nazi concentration camp—and remained in Raciborz in the employ of local Germans. She died in 2009.

Jews made up half of Lubaczów’s population before the war and represented the entirety of the town’s professionals. Teresia and Stasia told Kazik that after the war only one Jewish family remained.

Lubaczów, like so many other towns in eastern Poland, bore the brunt of repeated attacks from German and Russian armies. During one of the battles, incendiary bombs hit the Meder’s original wooden farmhouse, which burnt down. After the war, when Maria visited from Raciborz “in all her finery,” she struggled to recognise her family dressed in rags. Stasia and her husband replaced the temporary 32-square metre house in 1976.

In 1994 Kazik explored, stood where he used to play as a toddler, absorbed the ambience, and left content.

The farm’s well, which Kazik remembered, survived the WW2 bombing.

“I’m 81, so it did take a long time to find out all of this, but I think I’m there now.

“People hear my name and say, ‘Where’s that from?’ I say, ‘Poland,’ and they say, ‘Ah, you’re Polish then,’ and I say, ‘No, I’ve lived in this country longer than you have.’ ”

A fine line, and one Kazik knows all about.

© Barbara Scrivens, 2019.

THANKS TO THE TAKAPUNA BRANCH OF AUCKLAND LIBRARIES FOR THE LOAN OF AUDIO RECORDING EQUIPMENT.

UNLESS OTHERWISE STATED, ALL PHOTOGRAPHS FROM THE ZAJĄC FAMILY COLLECTION.

ENDNOTES:

- 1 - This photograph was taken at Kazik and Jan’s home at Easter, 2019.

- 2 - Even if the Bronisława’s age at the time of her father’s death and her marriage had been out by a couple

of years, Michael Meder’s death, circa 1917, would have fallen within the realms two infectious diseases: cholera and

encephalitis lethargica. According to the Encyclopedia of Plague and Pestilence; From Ancient Times to the Present,

edited by George Childs Kohn, Russia suffered a cholera epidemic from 1915–1922 (Lubaczów was until 1918 still partitioned

by Russia) and encephalitis lethargica plagued the entire European continent from 1915–1920.

It seems more likely that it would have been encephalitis lethargica, with its dramatic symptoms, such as paralysis, abnormal movements and spasms caused by a virus, that prevented Michael Meder from being buried in Lubaczów. The virus was first described by Constantin von Economo, a brain anatomist in Austria; Michael Meder was Austrian; perhaps he had caught the virus when he visited family?

Third edition, 2008, pages 100–101 & 475. - 3 - Translated words.

- 4 - Aleksander Gurjanow collated records of many of the cattle trains transporting Poles to NKVD forced-labour facilities in the USSR. His work is titled List of Deportee Transports via Rail 1940-1941 by Arrival Station, Karta, 12, 1994.

- 5 - Ibid.

- 6 - By June 1942, the Poles who had managed to leave the NKVD facilities had already escaped to Persia, or had reached the southern USSR.

- 7 - In this and other stories, I use the apostrophes to show that the so-called ‘amnesty’ was a

farce:

An amnesty is defined as an official pardon for those who have committed political offences, but the Poles taken by Stalin’s Secret Police, the NKVD, from Russian-occupied eastern Poland in 1940 and 1941 did nothing to deserve their abduction to the USSR. Hitler’s invasion of Russia was what forced Stalin to turn to the West for help. - 8 - https://www.britannica.com/event/Operation-Barbarossa

- 9 - The Second Polish Corps capturing Monte Cassino in May 1944 and opening the road to Rome for the Allies and the First Polish Armoured Division’s push through the Falise Gap in northern France in August 1944.

- 10 - https://www.warhistoryonline.com/world-war-ii/soviet-fighter-planes-wwii.html

- 11 - I believe that either John Pascoe or Noel Jackson, who both took many photographs at the Pahiatua camp, may have taken this one, but I can find no reference. If anyone can help, please write to me through our Home page.

- 12 - New Zealand National Airlines Corporation, which merged with Air New Zealand in April 1978.

- 13 - http://www.trinityhawera.co.nz/about &

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Walter_Powdrell - 14 - Image from the New Zealand Electronic Text Collection, NZETC, NEW ZEALAND’S FIRST REFUGEES: PAHIATUA’S

POLISH CHILDREN.

http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/PolFirs-fig-PolFirsXXXe.html - 15 - Born Teresa Vickers in Hastings in 1881, Sister Charles died on 15 December 1958. She has been remembered in a

website of the Sisters of St Joseph, Whanganui:

http://www.ssj.org.nz/index.php/sisters-of-the-past-whoweare-20/82-sister-charles-teresa-vickers - 16 - These names, and the ones in the paragraphs above are taken from the German booklet that Kazik’s half-brother Norbert gave him.