Marysia Dac Jaśkiewicz

Marysia Jaśkiewicz lives by the Polish saying, “Gość w dom, Bóg w dom.” (A guest

in your home is the same as having God in your home.)

Pani Marysia stood at the door of the Dom Polski (Polish House) in Morningside, Auckland, when I first walked in and

immediately welcomed me. Among the youngest of the Pahiatua children, she has grown up with the Polish generosity of spirit

when accepting guests, and is as much at home at the Dom Polski as her own home in Blockhouse Bay.

Besides her children, her grandchildren and her religion, Marysia treasures her Polish heritage. During holidays in Poland,

she surprises local people when she says she left as a toddler. Her command of the language is a reflection of her concerted

effort.

During our several meetings since 2013, we talked about doing an interview for this website. I am grateful that the time

arrived.

Parts of this story have been difficult for Pani Marysia to verbalise. Not because she does not know how to articulate what

happened to her and her family from 1940, but because so much of what she remembers of the following years, she would prefer

to forget.

Pani Marysia told most of her story in her mother tongue. Her quotations below are translated.

Many thanks to a thoughtful, kind and thoroughly decent woman.

—Basia Scrivens

A SIBERIAN ‘VACATION’

by Barbara Scrivens

Ten, kto nie szanuje i nie ceni

swej przeszłości

nie jest godzień szacunku

ani prawa do przyszłości.

- Marshal Józef Piłsudski1

To remember—and risk living in a solitary past—or to try to forget: Marysia Dac Jaśkiewicz remains torn that she cannot help but do both.

Too young to remember specific dates, places or details after her family’s forced exile to Siberia in February 1940, Marysia has not been able to shrug off the lingering memories. Injections, for instance, still frighten her.

Marysia’s older brother, Michał, told her she was 16 months when Soviet soldiers corralled the family and transported them on cattle trains to one of the hundreds of NKVD-run2 forced-labour facilities in Siberia. According to the karta index of the repressed they were destined for Mołotowska, in the Perm region of the Ural Mountains.3

“Instead of food, they punctured me full of holes.”

“The Soviets wanted me to go to the kindergarten… where they would bring me up. They told mama to go to work. Mama took me there, and then took me away. She left me a second time, when my father was very ill.

“I was so small. I lay on a child’s bed. Instead of food, they punctured me full of holes. The communists gave me only injections, all over, in my arms, in my hands, in my back… Everything hurt.”

Marysia does not know how long she lay in the Soviet kindergarten, but does remember the second time her mother, Rozalia, removed her.

“I came back ill, malnourished and unfed.”

Her father’s sudden disappearance not long before she left with her mother, brother and older sister Aniela became the only other definite memory that Marysia imbedded during the family’s nearly two-year stay in the forced-labour facility.

“They made him dig his own grave in the forest, then shot him. It happened to other people too. They never came back.”

_______________

Władysław4 Dac had some sort of inkling his family may be targeted by the Russians once they invaded Poland in 1939. He had taken the family several times to Austria in the months before, Marysia believes to plan an escape route.

“They told us to dress warmly as we were going to Siberia for a vacation.”

He employed “lots” of people in Przemyśl, where he owned a house and a business. His wife taught in a nearby school. He also owned a property in the suburbs, where he kept an orchard and a garden, and where the family were staying when Soviet soldiers surrounded the home.

“It was at night. They made a lot of noise. They told us to dress warmly as we were going to Siberia for a vacation.”

There was a large age-gap between the siblings and the oldest, Antoni, was visiting their grandparents. He remained in Poland as the soldiers led the rest of the family at bayonet-point to sleds, which took them to animal carriages waiting at the railway station. She remembers the date thanks to a song she heard, Dziesiąty luty będziem pamiętali jak na Sybir nas zabrali. (We will remember 10 February as the day they banished us to Siberia.) 5

In Siberia Michał joined his father working in the forest.

“If you didn’t work, you didn’t get food and my brother wanted to get some lepianka (a flat type of pita bread) for the family.” Marysia assumes that, after finding out the Soviets’ inhumane treatment of her, her mother looked after her while Aniela was at ‘school.’

World War 2 rumbled on. Hitler and Stalin had divided Poland between them in September 1939 and the Poles who had been transported to the USSR seemed destined to die there.

Hitler’s soldiers crossed that contrived Russian-German boundary in Poland on 21 June, 1941, and headed towards Moscow. Stalin joined the Allies and by 30 July 1941, his representative in London had signed an agreement with the Polish President-in-Exile General Władysław Sikorski: Poles had been given ‘amnesty’ 6 and were allowed to leave the NKVD facilities to form a Polish army on Russian soil.

“I was too little to ask anybody anything… I just followed my brother and sister.”

It is not clear why Władysław Dac and the others were killed in the forest. Michał had told Marysia that their father had been ill, so he may have been considered too weak to work, or the facility’s NKVD commander may have wanted a price for losing his Polish labourers.

Rather than allow the Poles immediate access to their army’s enlistment stations, however, the Soviets continued to use their labour in kolkhozes (collective labour farms) or labour-intensive projects in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. (See Wisia Sobierajska Watkins’ story, in and out of nowhere7 on this page.)

Marysia, growing up, became adept at listening for information, which is why she knows that they went to Kazakhstan. The rickety make-shift sleds they pulled are all she recalls of the journey.

“I was too little to ask anybody anything. We travelled with people. We went wherever the people were going. I just followed my brother and sister. Mama was not always with us.”

_______________

That group of Poles may have thought they were heading towards their army, but two-thirds of the nearly 3,000-kilometre route crossed Kazakhstan and they were steered instead towards one of the kolkhozes. Rozalia had led her children out of the forced-labour facility but by the time she reached the kolkhoz, she had become ill enough to warrant a hospital bed. Perhaps seeing her mother on one of the sleds cemented them in Marysia’s memory.

Local Kazakhstani residents had been ordered to accommodate the Polish influx but Michał, Aniela and Marysia spent many nights sleeping under trees or porches. During the days they scavenged for food and Michał kept approaching people for shelter.

“There was this Russian. He said there was no room in his house but we could sleep in the stable.

“We had nothing. When we left for Russia [in 1940], we had a house. When they let us go we had nothing. Everyone was dying.

“We said the Hail Mary with mama and they lay her down…”

“My brother found out that he had to fetch our mother from the hospital as she was ‘already healthy.’ The Russian man went with him and they brought her to the stable and put her down next to me. She told us that she would get up tomorrow and would feel better. We would find a better place to live and she would look after us again.

“I see the picture: I sat with her, wrapped up, and my mother told me, ‘Go and call the others to move me. I can’t move myself and I want to lie down. My back hurts.’

“So I went to call my brother and sister and they came. ‘What is it mummy?’ And she told us that she loved us, that we should live as Catholics, because we were Catholics, and we should pray to the Mother of God. We said the Hail Mary with mama and they lay her down and she lay there. She closed her eyes and did not wake.

“It was so very lonely. We did not have our father and now I yearned for our mother.”

Michał, Aniela and Marysia walked the streets looking for food, stealing what they could and searching for empty tins for cooking.

One day the older two left Marysia—then nearly four—playing with other Russian children. When they returned she had vanished.

“Because I was still little, I was playing outside with the other children, whoever they were, I don’t know. When the mother came to pick up her children, the little girl took my hand and I went with her.

“I was gone for weeks. My brother told me how they kept looking for me in places where there were children playing and one day they heard someone calling, ‘Marysia!’

“My brother told me how he came up to me and said, ‘Choć do mnie,’ and I went to him. And that is why my brother was to me like a mum and a dad and everything.”

Marysia has no memory of the time she spent with the Russian family.

“It is a blank, like I was not there. I know I must have been fed…

“I remember the bad things, what hurt.”

_______________

“…I saw the revolver and I thought I was going to die because he was shooting.”

One day the children came across a huge state vegetable garden protected by wooden fencing.

“We had no vegetables, nothing to eat and when we saw those vegetables… My brother and sister gave me some kind of large shirt, dug under the fence, and pushed me in. It was not only me in there—other children were also there, stealing.

“We got ourselves all sorts of green vegetables. There were potatoes and tomatoes. There were onions along the edge but I did not have the strength to pull them out. My brother and sister came to the fence and I gave them the tails. I pushed and they pulled.”

Michał and Aniela returned to their hiding place and Marysia to the garden.

Sudden, loud, heavy panting penetrated her concentration. She turned to see a dog running towards her. A man on horseback followed. The children had not known then that mounted policemen patrolled the garden. Armed with revolvers, their job included shooting at birds eating the produce.

“If he had seen me… I crouched under the greenery—I don’t know whether it was the potatoes or the tomatoes—and I cried because I saw the revolver and I thought I was going to die because he was shooting. He flew by me. My brother and sister saw everything and also thought I was no more. Later I crawled out and they pulled me from under that fence.

“I don’t know how I survived. That was the most frightening experience for me—and for them too.”

Michał, Aniela and Marysia ate the stolen vegetables like anything else they found—raw. Marysia does not remember returning to the garden and doubts her brother and sister would have made her go back.

Although they saw many other people eating frogs, the Dac children somehow never found one—and ignored any strolling tortoises that they had seen others pounce on.

“We never saw eggs or chickens, but maybe it was because I did not know what a chicken was supposed to look like.

“When I met him in England years later my brother told me he could sit down with me every day and tell me something different about what happened to us. He told me a bit here, and a bit there. One day it got too much and I said to him, ‘Let us go outside and get some fresh air.’”

_______________

“Those times will give you nothing,” he told her.

Michał’s contracting malaria in Kazakhstan saved the siblings, who remained living in the Russian’s stable after Rozalia died.

“The Russian didn’t know what to do with us, because I was ill too, and he went to find a doctor. I don’t know who it was, but they said there was a Polish army, and they notified them. They came and took us to an army camp where my brother went to hospital and I did too.

“We were for quite a while in the hospital. We got better and then the army took us to the boat to go to Persia [now Iran].”

That journey became another blank in Marysia’s memory and when she asked about it later, Michał told her to forget: “Those times will give you nothing,” he said.

“Maybe he had a point. Should we live through the past? We should live for the future, not the past.”

_______________

In Pahlevi, now Bandar-e Anzali, the Persian port on the Caspian Sea where they landed, Marysia ignored instructions to stay with her sister. She did not like to be apart from her brother and one day slipped away to follow him.

“There was a meeting in a house and I went under the floor and could hear them talking. When they finished, I quickly went back to my sister. My brother did not know that I had heard his plans to leave us and join the army.”

“He sat me on his knee… and fed me those walnuts… they saved my life.”

Michał had arranged with an orphanage to take Aniela and Marysia, leaving him free to join the junaki (the Polish Army's cadet school for teenagers).

“We cried, and said, ‘How will we manage without you?’ He said, ‘It will be better for you there. Someone will look after you and give you food, and I will go on my path and we will keep in contact.’”

Before he left, Marysia was in hospital with tuberculosis. Michał would buy walnuts and crack them outside the hospital gates while he waited for the 2pm visiting hours.

“He sat me on his knee with a blanket around me and fed me those walnuts. I know they saved my life. One day he said we were going to another hospital and he took me to visit Aniela. She had an operation on her feet. We spent a bit of time with her, and then he brought me back and then went back to his own camp.

“He did that every day. When he left Persia with the junkai I was still in hospital.”

Authorities placed the sisters in separate hostels in Isfahan, Aniela to number five for older girls and Marysia in nine, closer to the city centre and the beautiful Armenian (Ormiański) Catholic Church where she took her First Holy Communion.

“They made my dress from a sheet and took the curtain for a veil. I was still so sick, they thought I would die, so they wanted me to have my First Holy Communion.

“We were stealing and going to church! We didn’t know it was a sin.”

“We weren’t prepared. I don’t know if we even had a lecture about the catechism, why we’re receiving communion, what it’s going to do to us. It was just who was there got it, and it was done.”

Outside the hostels older girls and caregivers looked after the younger girls in huddled groups of four to six. The Persians then had a reputation for snatching fair-haired children. Marysia remembers the huge hostel gates and how, on the way to Mass, the girls passed laden grape vines and broke off bunches to eat as they walked.

“We were stealing and going to church! We didn’t know it was a sin. Fruit is fruit. We never had it. It was edible, so why not? Now I can think, but then I did not. It was growing and we wanted it.” (Marysia is still trying to find out the name of the deep-orange fruit they picked from bushes, the size of half a finger, no skin but “fluffy outside” and “beautiful to eat.”)

_______________

If it had not been for vigilant list-scrutinisers, the sisters may have landed on different continents after the New Zealand government joined eastern and southern Africa and Mexico in accepting Polish refugees in the latter stages of World War 2.

“I was in one hospital, Aniela in another, and the authorities did not know we were sisters. She was going to Africa and I to New Zealand—on the next transport—and they asked me if I had a sister. I said, ‘Yes, but I don’t know where she is.’ They asked my sister the same thing and she said she didn’t know where I was. Afterwards they sorted it all out and we came together to New Zealand.”

_______________

Along with a photograph someone took of her First Holy Communion Marysia treasures one of her in Pahiatua in a sheepskin coat that she received from the Red Cross. She leapt on it, repeating, “This is mine,” as she disappeared into its warmth.

“The army left its uniforms to Pahiatua so the older girls sewed gym dresses and berets for us…”

“It was almost to my knees and someone came with some safety pins, took out my arms and took a photograph. My beloved coat, I don’t know what happened to it.

“We then had food, a bed to sleep on and the Red Cross came with clothing, because in Persia we were barefoot and there was not much to wear. It was so hot anyway. So many of us have these crooked toes because they brought shoes and we pushed our feet into them so we would have shoes on our feet.

“The army left its uniforms to Pahiatua so the older girls sewed gym dresses and berets for us smaller girls to go to school and church on Sundays. We had cream blouses. I wanted to keep my uniform—it still fitted—but they made us give them back when we left the orphanage.”

Marysia loved her five carefree years at the Pahiatua Children’s Camp, known also as Pahiatua’s ‘Little Poland.’ It gave her stability and to some extent made up for losing her home, her parents and her brothers. She especially enjoyed being part of a Krakowski dancing group. Half the girls took on boys’ parts.

From left: Władzia Dalton (née Kubiak), Zdzisia Gurynów (née Kołodziej), Czesia Markowska (née Gazdowicz), Iza Ptak (née Wiśniewska), Irka Banaś (née Szadkowska), Wanda Makomaska (née Wierzbińska), Marysia Jaśkiewicz (née Dac) and Teresa Maggs (née Wypych).

Marysia left Pahiatua for Auckland at the end of 1949. Aniela had moved up two years’ earlier and attended St Mary’s College in Ponsonby. In 1946, once it became clear after the Germans were defeated that Poland remained under communist control, the New Zealand government gave the Polish refugees the option to stay. For girls in Marysia’s age-group, their Polish schooling did not change much. Until about six months before she left, she remembers having “maybe” one English lesson a week.

Even before 1946, as the Pahiatua children reached high-school age they became scattered among Catholic high schools all over New Zealand and lived in boarding schools or with foster parents. The Catholic Church, which organised the Polish children, would not allow them to be adopted, so that if family were found in Poland, the children would be free to leave New Zealand. Those without families in Poland would be allowed to review their decisions once they reached 21.

Aniela and Marysia bordered with different foster families, Aniela with a Mrs Murphy in Westmere and Marysia with a Mrs Wade at 21 Hopetown Street, Newton. The sisters met at school.

Marysia blesses Sister Ambrose for her patience in easing the Polish girls in her class into English lessons. She so loved and admired the nun with a “heart of gold” that, on her way to school, she often approached house owners to give her a few flowers from their gardens for her teacher.

_______________

Marysia became a dressmaker after finishing her schooling. She disregarded the Catholic Youth Centre’s advice to take a job in a factory. A friend in Wellington, Marysia Juchnowicz, advised her to follow her dream, even though at that time neither knew whether such a training centre existed in Auckland.

“I am not going to work in a factory. I am going to learn dressmaking…”

Marysia Dac walked among the city’s dress shops questioning the salespeople and followed directions to a dressmaking school on the second floor of a building at the bottom of Queen Street. She enrolled herself and told the principal to send the bill to the Catholic Youth Centre in Victoria Street.

When Marysia found out that another Pahiatua girl was already attending the same course, she became even more determined.

“The Youth Centre asked if I knew how much the course was going to cost. I said, ‘No, but I am not going to work in a factory. I am going to learn dressmaking here, and if not, I will go to the school in Wellington.’”

Marysia’s second foster mother, May Cairns, backed her and she finished the two-year course in one.

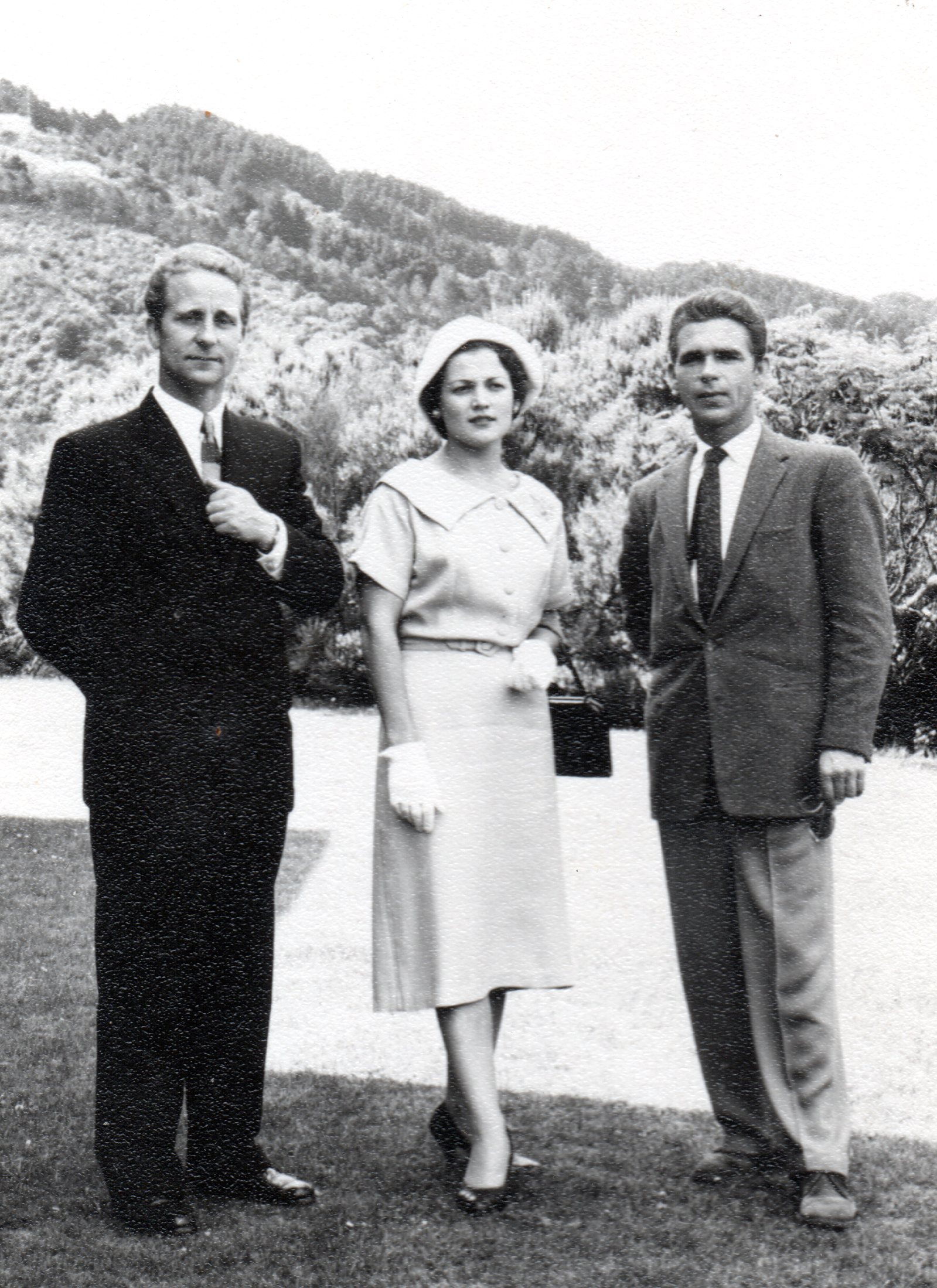

Marysia was still in dressmaking school when she went to Wellington in 1958 for the farewell functions of Pahiatua priest Fr Leon Broel-Plater, who was transferred to France. She made this ensemble. On the left is Staszek Panek. (If anyone can identify the man on the right, please let us know through the get in touch function on our home page.)

Marysia is between Fr Broel-Plater in the middle and his replacement, Fr Lukasz Husarski, on the left.

_______________

The Red Cross helped the Dac sisters find Michał in Stockport, England. He had served with the Second Polish Corps in Italy and was injured during the battle for Monte Cassino. Marysia hungered to see him again and held three jobs to save the fare. She calculated it would take her three years, and was well on track after two.

“I was working in an Italian restaurant when 12 Pahiatua boys walked in.”

One was Franciszek Jaśkiewicz. Marysia, until then not sure whether she would return from England, listened to her sister’s mother-in-law, “babcia” Katarzyna Dobrowolska, who told her, “Marysia, I like him.”

Marysia on her wedding day, 22 April 1961. She made her own wedding dress and her bridesmaids’ dresses. Her three daughters wore her coronet and veil for their First Holy Communions.

Franciszek and Marysia Jaśkiewicz with their entourage outside St Mary’s Catholic Church in Avondale on 22 April 1961. The groomsmen were Edek Dobrowolski (left) and Staszek Jaśkiewicz. The bridesmaids from left: Helen Frost (née Dobrowolska), Halina Wakefield, Stasia Markowska and Hania Dobrowolska (née Stotska).8

At the entrance to their reception the newly married couple were greeted in the traditional Polish way, with bread lightly sprinked with salt and a glass of wine. Marysia’s sister Aniela, her husband Czesław Dobrowolski and his mother, Katarzyna (far left) stood in for Marysia and Franciszek’s late parents and gave their blessings for their future life's abundance.

Marysia continued writing her weekly letters to Michał, and settled down to raising Zdzisiu, Marysia, Basia and Krysia.

Above: Marysia with ‘babcia’ Dobrowolska and the four Jaśkiewicz children. Right: Zdzisiu and Marysia.

Krysia was five when Michał’s wife, also Marysia, sent a telegram to say that Michał had had a stroke and was asking for his sister. When she told her husband she was determined to visit him, Franciszek said, “But we have four children and no money.” Marysia did not question how the cost of the fare appeared in their bank account, but within 10 days, she and Aniela flew to the UK.

Michał’s health returned and Marysia basked in the company of a brother she considered her “mother and father rolled into one.”

Her ears pricked up after a Polish Mass in Manchester: The president of that Polish association read out Antoni’s name among those who were looking for lost relatives. Michał, after hearing countless similar announcements, had not been listening and dismissed it but Marysia urged him to meet with the president and leave their address details.

A while after returning to New Zealand, Marysia opened the door to two policemen: Antoni had written to her.

Once her daughter, Marysia, finished her degree, she announced that she was taking her mother to Poland, telling the family one dinner-time that their mother would not be happy until she went there. That trip, in 1987, included a visit to Antoni, who then lived near Wrocław.

“He told me that when we got there, we should phone him. I did and told him we were at the main bus station opposite the post office. He said he would fetch us. I asked how long it would take him. He said two hours…

“We had a wonderful time. He lived on a large beetroot farm. He had a house and chooks, a wife and a daughter. He got married during the war and had five children but the Russian gestapo killed four of them. I don’t know what age they were because he burst into tears when I asked. He had one daughter left.”

Michał and Antoni also met in Poland but the four Dac siblings continued to live in three separate countries. Michał died in 2003, several years after Antoni. Aniela never did reunite with her older brother.

_______________

The former Pahiatua children in Auckland kept in touch with one another. Their loose meeting arrangements became an official association in 1960, Aniela’s husband Czesław the first president. Aniela became known as Angela, had two children, Jan and Helena, and died in 2005.

Marysia and Franciszek, too, were members from the start. When Franciszek died in 1994, Marysia continued to serve the Auckland Polish community, and is still a guiding presence.

When members of the association heard that His Holiness Pope John Paul II would visit Auckland on 22 November 1986, they were determined to give him a proper Polish welcome.

They commemorated their planning meeting in October 1986 with this photograph. All the names are from left.

Back row: Tadek Pąk, Zbyszek Pyrzewski, Maczek Suder, Franek Zazulak, Wacek Kupidura,

Longien Krzewski, Franek Kubiak, Karol Murdesiewicz at the back, Jadzia Frykowska, Jurek Pisarek at the back, Henek Pąk and

Cela (née Gawlik) and Antoni Zazuluk.

Middle row: Jan Jarka, Polish parish priest Fr. Stanisław Rakiej and Danka Kupidura (née Łakoma).

Front row: Ignaś Pąk, Albin Goj, Franciszek Jaśkiewicz, Marysia Jaśkiewicz, Marysia Suder, Wisia Schweiters (née Rubisz) and

Zenia Pąk.

Dressed in traditional Polish costume on the day of Pope John Paul II’s visit to Auckland, from left, Jadzia Cooper (née Jarka) and Basia and Marysia Jaśkiewicz. (Photographer unknown)

The bonds Marysia made in Pahiatua remained. At the 6oth anniversary get-together in Silverstream are standing from left: Irka Banaś (née Szadkowska), Marysia, Francia Quirke (née Węgrzyn), Mila Wypych (née Banaś), Marysia Wypych (née Depczyńska) and Jadzia Gil. Ola Kraczko is in front.

Marysia made the dresses and hats that she and her daughters wore for Zdzisiu’s wedding in 1998. From left, Basia, Krysia and Marysia.

One of the things Marysia is most proud of is that she has kept her Polish heritage alive. She made sure their children had Polish names, and immerses herself in her language whenever she can. When she stayed in Poland for a time with former President of the Auckland Polish Association Dr Thomas Gorecki, he woke her late one night to ask her to speak to his students the next day.

“I didn’t have time to prepare so I spoke from my heart. They stopped writing. By the time I finished, I saw quite a few tissues.”

© Barbara Scrivens, 2017

ALL PHOTOGRAPHS FROM THE JAŚKIEWICZ COLLECTION.

THANKS TO THE NORTH AUCKLAND RESEARCH CENTRE IN THE TAKAPUNA LIBRARY FOR THE LOAN OF AUDIO RECORDING EQUIPMENT.

ENDNOTES:

- 1 - The statue of Józef Piłsudski overlooks Piłsudski Square and the Tomb of the Unknown

Soldier in Warsaw. This quotation is one of three on the plinth and translates as:

The person who does not respect and value

his past

is not worthy of respect,

or the right, to a future. - 2 - NKVD, or People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs, were part of the USSR’s secret police. They organised the population of, and ran, the hundreds of gulags and forced-labour facilities in the USSR.

- 3 - The listing from KARTA’s Indeks Represionowanych shows Wasyl, Rozalia, Michał, Aniela and Maria “Deportowani w obwodzie Mołotowskim (Permskim).” Listings found through: http://www.indeksrepresjonowanych.pl/int/wyszukiwanie/94,Wyszukiwanie.html

- 4 - KARTA has Władysław’s name as Wasyl.

- 5 - This stanza from

http://na-sciezkach-codziennosci.blogspot.co.nz/2015/02/dziesiaty-luty-bedziem-pamietali.html:

“Dziesiąty luty będziem pamiętali…

Przyszli Sowieci, gdyśmy jeszcze spali,

I nasze dzieci na sanie wsadzili,

Wszystkich Polaków na Sybir gonili.

Przez cały miesiąc transportem jechali,

Ginęli z głodu, z zimna umierali.

A na tym Sybirze tajga, straszna bieda,

Ale nasz Polak wrogowi się nie da,

Nie da się wrogowi, nie ugnie kolana,

Chociażby miał zginąć, ojczyzno kochana.

Polsko ukochana, ty nasza miłości,

Wrócimy do ciebie, jak da Bóg wolności!” - 6 - I use ‘amnesty’ in inverted commas because, although Stalin and others used the term, the kidnapped Poles had done nothing to deserve their incarceration, and therefore did not need amnesty.

- 7 - http://polishhistorynewzealand.org/in-and-out-of-nowhere/

- 8 - Photograph by Natural Photographers of Lagonda House in Queen Street, Auckland.