Michał Pąk & Zenona Cyckoma Pąk

My first drafts of Michał and Zenona Pąk’s stories separated them in slightly different sections of this website, but both had something missing: their stories lacked the input of the other.

Although Michał was not a displaced person in the sense that Zenona was—in the British Zone of post-war defeated Germany between 1945 and 1950—he was most definitely displaced from his immediate family from 1940 to 1956.

Dictionary meanings for displaced include dislodged, dislocated, relocated, or, simply, moved, and that is exactly what happened to Michał. He was among the hundreds of thousands of Poles born and living in eastern Poland at the end of WW2 in Europe, who were forced by the new post-war communist-controlled regime in Poland to relocate to the western side of the so-called Curzon Line.

Michał and Zenona arrived in Auckland separately as teenagers at a time when the Polish community in the city was establishing an official association. The post-war Poles already settled in Auckland, such as veterans who arrived from England, played a huge part in their integration. Michał and Zenona, now married for nearly 60 years, reciprocated through their commitment to the Polish community, and were among the many who helped establish the Auckland Polish Association and build its Dom Polski in Morningside.

I thank them for their time, their patience, and their generosity.

—Basia Scrivens

WHAT BECAME OF THEM

by Barbara Scrivens

After Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, farmer Michał Pąk senior began to hurry. A veteran of WWI and the 1919–1920 Polish-Soviet War, he expected to be called into the Polish army at any time.

When no call-up arrived, Michał, and other men in the osada Jałówka, near Prozoroki, went to Wilno to enlist, but were told they were not yet needed. They monitored the advancing German front through a radio held in a Jałówka watchtower, a few kilometres from the USSR border, and listened to Russian broadcasts. They heard that the Red Army was ready to send troops to ‘help’ the Polish army. The Poles said they needed armaments only, which did not arrive. The farmers listened to the Russians’ repeated requests to the Poles to repair roads and bridges for Russian tanks, but heard nothing about any Polish mobilisation.1

One day, Michał’s youngest son, 18-month-old son, Michał Faustyn, wandered from his mother and brothers to the outer reaches of their farm, and found him scything hay.

Michał senior: “I noticed a child in front of me, standing bare-footed in the grass. He was very serious, and very unhappy. It was Michał. I was surprised that he did not approach me nor wanted to be picked up, but with a very sad air on his countenance just stared at me.

“Something came over me. I felt that we will be parted. Looking at his serious face I could not scythe any more. I threw the scythe down, picked up the child and took him home.”2

Back in the farm kitchen, Zofia Pąk, busy farmer’s wife and mother of four boys, dismissed her husband’s premonition that “fate” would separate them.

After that incident, Zofia developed toothache and needed to get to the dentist in Głębokie. She and Michał decided that he would take her and the infant Michał to her parents in Hołobicze while a neighbour looked after their other sons. Someone else would take her to the dentist the next day to allow Michał senior to return to the farm.

The next day—17 September 1939—the Russians did arrive in Poland, but not as friends. Cries of “War!” and “Bolsheviks!” accompanied by immediate looting and shooting left no doubt of the Red Army’s intentions. The invaders drove along the open roads. Michał returned home through the forests. Zofia followed alone a few days later, having left young Michał with her parents.

Local Ukrainians saw opportunities in supporting the Soviets, and soon purloined much of the Polish farmers’ crops and livestock. They took administrative roles from the Poles, who were forced the next month to vote in a communist-controlled election. In the meantime, Michał made ham and bacon from his three fattened hogs, and hung the produce in the loft. He found hiding places for extra sausages, lard, and reduced butter that he stored in containers.

Late in January 1940, Michał’s brother Józef and father-in-law, Stanisław Moraszko, visited the Pąk farm to make joint plans to save their properties. Zofia declared that she needed to return with them to Hołobicze, so that she could again visit the dentist in Głębokie. Michał suspected that the pain of missing her youngest son was greater than any toothache, and she again dismissed his “funny feeling” about her trip.3

She was due to return home a week later, on Saturday 10 February.

At 3am that morning, local Ukrainians accompanied by a Russian officer banged on the Pąk’s farmhouse door, and pushed their way inside. They forced Michał (42), Henryk (13), Tadeusz (11), and Jan, who had just turned seven, from their home, and sent them to the railway station in Ziąbki. A cattle train waited to remove them, and 1,600 other Poles destined to live out their lives in NKVD-run labour facilities in the Archangielsk region of northern Russia.4

_______________

Michał senior repeated the incident of seeing his son in the field to Zenona Pąk, whom Michał Faustyn married in New Zealand in 1962.

Zenona: “He looked up and saw his son struggling to walk through the grass, and he knew he had been sent to bring him in for lunch. He said he didn’t know why, but he looked at Michał, and thought, ‘Dear God, my son, what’s going to become of you?’”

Michał: “Because I was at my grandmother’s place with my mother that night [10 February 1940], we got separated.

“The politruks told my father to take as much as he could, and he had meat and fat. The port fat, marinated—słonina—we eat there like cheese here, so he had plenty of that.”

In his memoir, Michał senior recalled that although he had meat, he had not had time to go to go to the mill for flour, and neither did the boys have clothing appropriate for the conditions in northern Russia. Before telling the Polish veteran that he had 15 minutes to pack to leave his home, the NKVD officer made him walk up and down the street knocking on his neighbours’ doors. He first woke his immediate neighbour, Konstanty Dziakiewicz, then the Bojar household of 10 people, the widow Turkiewicz with nine children and in the last house in the street, Jan Massan, who had two daughters and a baby born in 1939.5

The NKVD officer asked after Zofia, who no doubt had been on his list, but did not mention his youngest son. Michał senior believed that someone must have warned Zofia to hide, but he did see her brother at the edge of the forest on the far side of the station.6

Michał senior called the cattle carriages “tiepluszki.”7 They had double doors, rough bunks, a tiny window covered with two iron bars at the top, and were tossed over the ill-built Russian railway lines. There were so many people squashed inside that he was forced to sleep seated next to the door. The first time he woke, his hair had frozen to the side.8

Michał struggled to keep himself and his older three sons alive in Diabrino, an NKVD facility that, by June 1940, eventually held 566 Poles.9 Life in the forced-labour facilities revolved around being able to work for a daily quota of bread—a quota not measured in any fair way. Although Michał managed to continue working, and Henryk had a job at one stage, father and sons became increasingly weaker. When, after 19 months, he heard the news of an ‘amnesty’ for the Poles, Michał lost no time in looking for the promised Polish army being formed on Russian soil. (For more details about the so-called amnesty, see the military timeline from 30 July 1941.)

In 1939, Stalin described the Poles as “anti-Soviet elements” but, after Germany invaded Russian-occupied Poland on 22 June 1941, he saw their usefulness in his battle against his former ally, Hitler.10 Stalin agreed to an ‘amnesty’ because he wanted to use the Polish men to protect Moscow. By then, Polish army commanders had long learnt not to trust the Soviets, and endeavoured instead to get as many Poles as possible out of the USSR.11

As another Russian winter closed in, Poles made their way thousands of kilometres south to the Polish army’s enlistment stations. Michał sold what he could to pay for trains, but quickly found out that the crowds hid thieves ready to take anything from anyone, even people in rags. When he realised that he could not look after his sons, he put them temporarily into the care of an orphanage in Yangiul, near Tashkent. When he saw them again, they were starving, sleeping on the ground in a freezing tent, and Jan close to death.12

Michał made sure that Henryk and Tadek, who were old enough, joined the junaki, the Polish army’s military school. He left Jan in the care of a Mrs Morawska, and enlisted into the Polish army. They all left the USSR in August 1942, under the auspices of the Polish army. They travelled from Krasnovodsk on the Caspian Sea to Pahlevi in then-Persia, now Iran. Their two-and-a-half years’ ordeal at the hands of the Soviets had been brutal, but they could, and did, recover.

_______________

By August 1942 Polish civilians in eastern Poland like Zofia Pąk and her son Michał had watched their land invaded by Germans from the west and Russians from the east, and had seen those Russians overthrown by Germans as they embarked on Operation Barbarossa in June 1941. Polish prime minister in exile, General Władysław Sikorski supported the formation of an underground resistance, the Armia Krajowa (AK, or Home Army) in June 1940. The AK grew to 200,000 active soldiers and civilians but had supplies for only a fraction of them.

Any Pole still clinging to the hope held within the Polish army’s motto “For Our Freedom and Yours” would have had it had it dashed during the August 1944 Warsaw Uprising. The AK battled the superior strength of the Germans still occupying Warsaw and waited in vain for their allies to deliver promised aid. At the same time, Stalin’s troops, on the allied side since June 1941, watched from the east of the Wisła (Vistula) river, and hindered any attempt by other allies to help the Poles.

_______________

Michał junior has few, tenuous memories of the Jałówka farm: seeing a distant fire—which he believes was connected to the first German invasion—and visits from an uncle.

“He used to play a mouth organ. He kept in on a little ledge on top of the window. I can’t remember his name. I had lots of uncles.

“Father’s family were mostly from the Lublin area, Zamość, but father was in the army when Poland got independence in 1918, and for his services [in the 1919-1920 Polish-Soviet War] he got a bit of the land that we gained after independence. Just empty land, so he had to clear it, and he built a house, then met my mum and got married.

“Before he was taken away [by the Soviets in 1940] he built a bigger house. His family was growing, and he finished that house, and he had a business too. He was a farmer, and he did everything. At one stage he had a what they called knajpa—he’d sell drinks and food; he made sausages.

“Because we were on the border of Białorus and Poland, when I was young, I could speak Białoruski, or understand it, and Polish. And the uncles, a lot of them spoke Białoruski, because they mixed with locals, and they could speak with the Russians too.

“I remember my grandmother’s place, the farmhouse, and my grandfather there. My father brought his brother from Zamość, and he lived next to my grandparents, in a little cottage. He had a nasty rooster that scratched me. I’ve still got the scar on my nose.

“I remember the partisans, uncles coming from the forest at night-time sometimes, specially one uncle, who married my auntie.

“When the Russians started rounding up people, a lot of them went into hiding in the forest and formed a partisan group. The Russians were saying that even forest people who were educated knew more than the ordinary worker: all the educated people were taken out straight away. They wanted it so that the people left behind, mostly couldn’t read, so they couldn’t pass on any information. People who could read, they kept it to themselves, because as soon as the Russians found out that somebody could transmit or write something, they were off to Siberia…

“There were a lot of forests. Every now and then, at night-time, the partisans visited their families. Otherwise, they were in hiding. What they were doing, I don’t know. Once, we were minding cows and sheep in a paddock with some friends when wolves started running towards the sheep. A girl, much older than me, started yelling, “Wolves!” It didn’t bother them. They kept running towards the sheep, but a partisan heard the yell, fired a gun, and scared the wolves away.“

As the wife of a Polish-Soviet War veteran, Zofia knew her fate if she had been identified by the occupying Russians. One of Michał junior’s dominant memories of the war was hiding, “travelling on the road, some distance” to different friends and relatives, and living with them for short stints. The moderate safety that Zofia’s father’s farm provided died with him in 1942, although by then the Germans had re-taken eastern Poland.

“I remember that there was nothing to eat and Mum was struggling. I think that when she got something [to eat], she was leaving it for me, and she was hungry. I remember walking 70 kilometres, Mum and me. A German patrol was coming through, and Mum asked one of the soldiers if they could give us a lift. The German just pointed to the back, to show us the transport of army that was behind him. They were going somewhere in a hurry, so they wouldn’t pick us up. It must have been summer, because it was hot.”

Michał junior and his mother had met Operation Barbarossa troops bound for Moscow.

“I could see at night-time the tracer bullets flying through the horizon. I could see the glow of places getting burnt down by the Germans.

“I was only about five, so it’s not completely clear, but we stayed with some of Mum’s friends for a while. I don’t remember the bombs falling, but one day when I woke up, all the windows were blocked off with cushions and the beam above me had a scar in the timber as long as I was. The roof was held up by beams—like all wooden houses—and in eastern Poland, they had fireplaces where they cooked, quite big fireplaces; the bricks warmed up, and people used to sleep at the top. I was up there, and I looked down. The shrapnel went through the wall, injured the man, hit above me, and I didn’t hear a thing. There were five bombs dropped right around and none of them hit the house, but all the windows were blown out.

“When the war finished, Russia took over and we were evacuated—the Poles that were left behind, not sent to Siberia—transported to existing Poland now.13 I remember German prisoner soldiers on the station and another train with Polish people going the same way.

“Babcia and some uncles stayed behind. The youngest of the uncles came with mum and me. When we got to [the new western] Poland, they dropped us off. I went to school straight away, because it was 1945. Uncle Antoni went to look at farms, to choose a house. The land was occupied by Germany before the war, and they gave it to Poland after the war. So people from eastern Poland were sent to those farms. Uncle found a place, and we moved onto that farm—he wasn’t married then—and that’s why I still could carry on going to school.

“Three other uncles moved to the same area. Two of them went more west, but one uncle, Józef, was about 10 kilometres’ walk from the town Orneta. During the school holidays I used to stay at his place. He was my godfather.

Michał, right, aged 12 with his uncle Józef, seated, his aunt Józefa next to him, his uncle Antek standing. Michał cannot remember the names of the woman standing, or children.

“There was a lot of land in the German farms. Rich people had bigger farms, maybe 50 hectares or more, and then there were small properties and houses. When the new [communist-controlled Polish] government got formed after the war, they subdivided the land—for each farmhouse, 10 hectares of land. So you could pick the house and the land around it, because people had a choice at that time, which house, which land. They didn’t want too much wet ground, too much forest, or not enough land, and so people picked what they thought would be most suitable for them to start life again. Uncle Józef’s farm had a bit of a swamp area, but the rest of the land was pretty good, whereas we had a farm close to the lake, and a small pond, but the soil wasn’t as good, and what you can grow all depends on the soil.

“What the new government did, was transfer people from a place like Lwów, from the southeast part of [pre-war] Poland all the way up to the northwest of [post-war] Poland. It was confusing. The people that they shifted from the east, they spread all over the place. They broke up the old communities, so the people wouldn’t have that communication, but they didn’t know at the time. Old neighbours lost touch. They couldn’t correspond with each other.

“It was a strategy the new government had, dividing the old communities, and mixing people.

“Why, from the east of Poland, send people all the way to the west of Poland? Why not closer? And mixing people? Each part of Poland had their own traditions, more or less, and dialect. You could tell that one came from here, that one from there, but once they mixed them up, you didn’t know where people came from.

“Once the dialects and traditions were gone, it was easier for the communists to control people, because when you have a strong group with strong traditions, if you break them up, they’re easier to handle. That’s how they did it.”

_______________

Poland’s new post-WW2 borders displaced both ethnic Poles and ethnic Germans from their former eastern territories. Together, the so-called Big Three—Britain, the USA, and the USSR—moved Poland’s pre-war border with Germany westwards, and expelled the Germans living there into what was left of Germany. Although the boundary changes profoundly affected the citizens of both nations, neither Poland nor Germany had a say in the decisions.

According to some researchers, this forced relocation affected 12-million Germans and 2.1-million Poles from Poland’s pre-war eastern territories, but as with any type of statistic, the numbers do not reflect the full story: The war’s bombing of Poland had left cities in ruins throughout the country, and millions more homeless. The new western territories became an obvious place to house them.

Michał: “They shifted people from regional Poland too, because everything was destroyed in the war. Warsaw was destroyed by the bombing, and many people left. When I started school, we all had a different dialect. It took quite a few years before we integrated and started speaking the same language.

“There were also places, like the Mazury in the [pre-war] German corridor. Mazury was part of Prussian Germany and Germany didn’t allow Polish education, or even Polish Catholic books.14 They weren’t allowed to, but they still passed on their Polish language through their prayerbooks. A lot of people there were Poles, but they were integrated into Germany, so when the war finished, if they felt they were Polish, they stayed behind. Some felt they were more German-like, so they went to Germany. Even the ones who felt more Polish knew that communism was taking over [in Poland], so had to decide whether to stay behind, or go.

Zenona: “They called them the False Deutsche. A friend of Mum’s did that. When it suited him, he was German. When it didn’t suit him, he was Polish.”

Michał: “It was the same with Ukrainians, and in Belarus. Because they could speak another language, they did what was safer for them.”

_______________

At 45 and with the Second Polish Corps in Iraq in 1942, Michał senior was, in his words, “a skeleton… of no use for other, harder tasks”15 He found his military niche in the army’s Field Hygiene organisation, serving in the 5th Kresowa Infantry Division in Italy.

In 1944, Mrs Morawska wrote to him, saying that authorities at the Isfahan children’s camp where Jan was living wanted to send him to New Zealand. His father agreed.

Even if Michał and Zofia did not correspond regularly, Michał, like all the surviving Polish soldiers, was well-aware of the political situation in Poland as the war ended. He arrived in England in September 1946, later joined by Henryk and Tadeusz.

Michał junior: “By that stage he was sending letters to Mother, and sending parcels. He sent me a box-camera, wooden, and I started taking my first photos. Father was too scared to go back to Poland because, as a soldier, he knew he would be taken again by the communists,and senet to Siberia, like they did before. But he was communicating with Mum.”

Communicating with Jan in New Zealand was not as easy. Aged 11, Jan had arrived on 31 October 1944, with 732 other Polish children, many orphans, and 105 adults who had been designated as their carers. Mrs Morawska was not among them. She and four of her children were sent to Lebanon.

“My father came here because of Jan. He was taken in by a family, and they wanted to adopt him. Father asked Mum, ‘What should I do?’ and Mum said, ‘Go to New Zealand.’”

It was not as simple as that. New Zealand authorities at first denied Michał’s application, then allowed him, Henryk and Tadeusz entry for a year. Michał (51) and Henryk (23) appear on the passenger list of the empire star, which arrived in Auckland from Liverpool on 9 January 1949.

_______________

Getting Zofia and Michał out of communist-controlled Poland took another seven years.

“Father started procedures to get Mum and me out of Poland when I was 11. That was when we sent out photos for the passport applications. By the time they let us go, I was 17, nearly 18, and they used the same photo on my passport. The customs people looked at the photo, looked at me…

“And they say the sierotki (orphans) had it tough. Two years in Siberia and two in Iran, and then they came to New Zealand, and they had already a home and food and all that.”

Zenona: “He didn’t know his father at all. He didn’t know his brothers.”

Michał: “The uncle who lived with Mother, Antoni, he was like a father to me, but it was different when he got married. Mum transferred her half of the farm to him, so she’d be free in case they let us go, so she had no ties. Again, we were shifting. Mum at that time used to live at a parish. She was a housekeeper for the priest. I finished standard school and went to higher education, boarding all the time in Olsztyn, and Mum started moving here and there. I was four years at the boarding house, and Mum shifted to her family, then to Father’s family near Zamość, stayed here and there for all those years that we waited until we could leave Poland.”

Michał aged 15 or 16, when he attended the technical college in Olsztyn.

“When Mum was with Father’s family in Tomaszów Lubelski, I moved school to the Zamość area, closer to Father’s family, so during school holidays I used to stay with Father’s sister, Maria, and I worked on the government farm, because her husband was running it.

“All those big areas of land that people had, the government took over. As far as you could see, it was just fields. I was about 16 or 17 and was on the bulldozer, a tractor with caterpillars. It was a big machine. You could not turn the key to start it like a tractor. You had to first start another engine on the side, then try and start the main machine. And I was a skinny guy! They took me up to that paddock, and I went up and down, up and down, ploughing by myself. Nobody there.

“I remember the engine overheating. I was running out of water to top it up, but I could see in the distance a forest, and knew there was a village there, and a well. When I jumped out to get the water, Ukrainians came out of the houses and chased me out, so I turned around to the bulldozer and took off. They were farmers. They had scythes. I wasn’t going to argue with them. I left without the water.”

Zofia’s continual moving and Michał at boarding school meant that he spent more time with his mother’s younger sister, Julia, than his mother.

Michał describes his ciocia Julia as his constant mother-figure in Poland, and was delighted when she was able to visit the family in New Zealand. Ciocia Julia was just as interested in Michał’s life and family. This photograph was taken with her grandniece Regina after a Polish Mass.

“She was looking after me when Mum was still in hiding or working somewhere, and I remember Father’s brother, stryjek, Józef—because he lived near there—and his children.”

Michał’s mother may have had another reason to allow her son to be cared for by his aunts and uncles. The communist-controlled post-war government in Poland infected its paranoia among the citizenry, so by keeping her distance, Zofia Pąk reduced the risk of upsetting their plans to reunite with their family in New Zealand through Michał or someone in the household inadvertently repeating something she may have said or done.

“In Poland after the war, parents didn’t talk much to their children, because at school the teachers would often put questions to them: ‘What are your parents talking about at home?’ ‘What is your life like at home?’ The children might hear something, but not realise what it means, and at school, during a discussion, they might say something. And the teacher would say, ‘Ah, so your parents are listening to radio wolna,’ or reading some banned magazines.’

“People didn’t talk much about what was happening. The kept to themselves, and so the children didn’t get that much knowledge from their parents.”

_______________

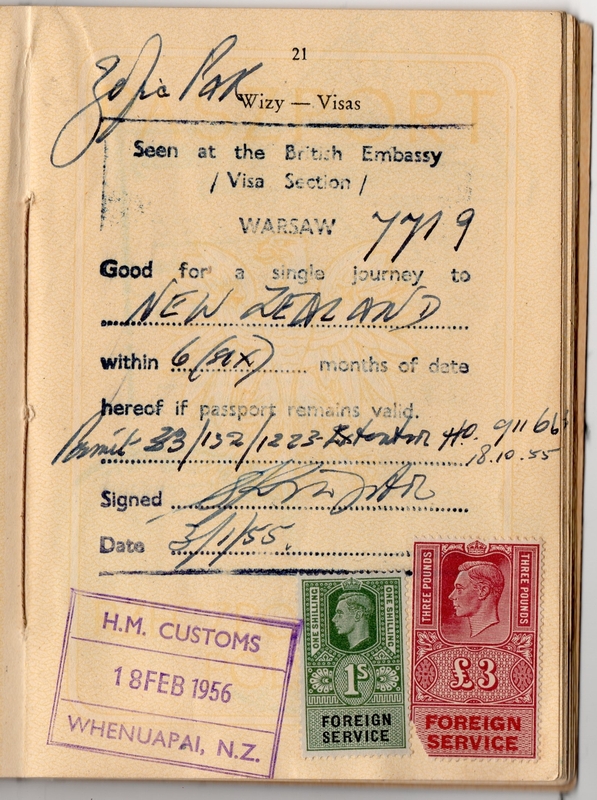

Zofia and Michał Faustyn Pąk arrived at Whenuapai on 22 February 1956, the only Poles on the multiple-legged flight.

“We were the first ones let go by the Polish government at that time, the first ones who legally left Poland. It took us, I think, 10 days to arrive by plane. I was 18. I had my birthday on the way. We went from Poland to Germany, then Zurich. From there to Italy. From Italy to Cairo. From Cairo to India. From Calcutta to Darwin, Darwin to Sydney, and then from Sydney to New Zealand.”

Zofia Pąk’s visa entry into New Zealand, in her Polish passport.

“From Cairo to India, we were flying through the night. I was asleep, but people were terrified because they thought there was something wrong with the plane. It was just a bit of a rough ride. We stayed two days in India, in a motel somewhere out in the country, nothing else right around. We could see little clay huts in the distance, where the locals lived.

“My first vision of New Zealand was that it was not a very pleasant country to look at. It was overcast when we arrived. Commander Francki had a jeep and he picked us up from the airport with my father, and when we came out of the airport, we couldn’t see anything except grass and gorse.”

Zenona: “Commander Francki helped a lot of the Polish people settle in, helped them with documents, advised them. He was a person who everyone looked up to. He would help you with all legal matters, and steer you to where you need to go to get help. For years he was a gardener, and yet he was such an educated man. He never looked down on you. He was amazing to so many of us.”16

Michał: “Lincoln Road was a country road. We were driving through wilderness, blackberries, and gorse, and a few bushes here and there, so it wasn’t a good impression.”

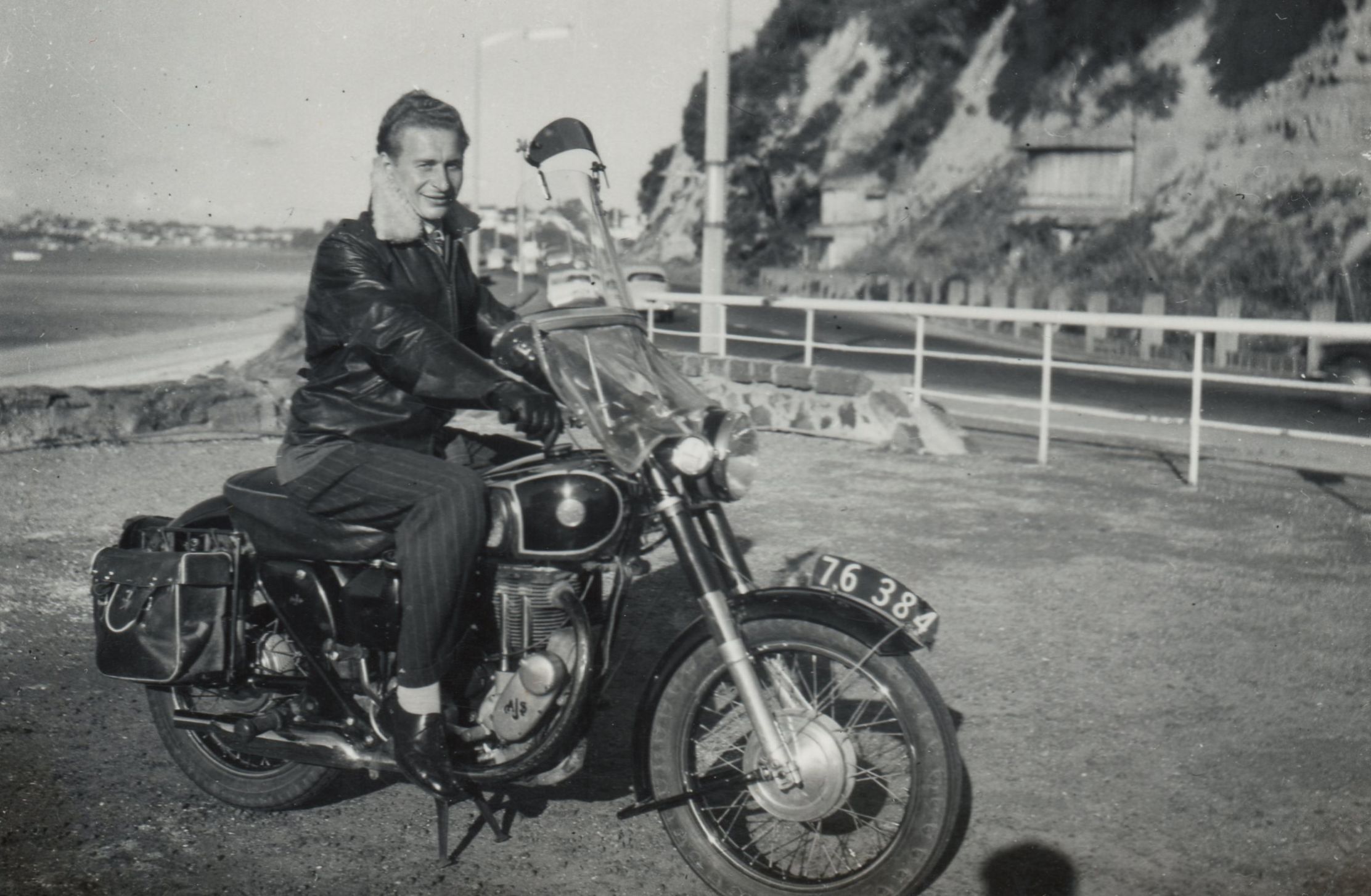

By then, Michał senior had bought a house in Glen Eden on four acres, where he had almost 200 ducks, chickens, bees, and a cow, Gizela. Zofia started making cottage cheese and cream, Michał junior bought a motorbike, and helped deliver his mother’s cheeses, honey, and eggs to customers who included a certain Mrs Emilija Cyckoma, who had a daughter, Zenona.

Michał off Tamaki Drive in Mission Bay, Auckland.

_______________

In Zenona, Michał found someone who had also spent several uncertain years waiting for others to decide their fate. Before the Soviets had forcibly removed Michał’s family to the USSR in February 1940, the occupying Germans soldiers in western Poland had already started to round up Poles to use as forced labour in Germany. Zenona’s future parents, Józef Cyckoma and Emilia Szczecina, both then 15, were captured by the Germans from their village near Kielce.

Zenona was born in June 1943, at a German labour farm in in Bremervörde, Germany, where her mother worked as a prisoner-labourer. She has little memory of her life on the farm, but her mother told her that she used to sneak out at night to milk the cow “straight into a bottle” so she could feed her.

An estimated 2,280,000 displaced non-Germans remained in defeated post-war Germany in July 1945. In the previous two months, millions more had been repatriated. Of those remaining, the largest nationality were 891,000 Poles17 who refused to return to a communist-controlled Poland. For the next five years, Zenona and her family lived in Lebenstedt, displaced persons camp 18 in the British zone.

“I remember the long barracks with rooms off a single corridor, and mum telling me and my brother to be quiet before she locked us into our room. She couldn’t trust anybody to look after us when she went to the kitchen to make meals for everyone—they had a roster for the women to cook, and they fed us in dining rooms.

“We had a tiny bedroom with a little wee window up there with bars. In the passage, we could hear women fighting, screaming, kids crying, running around, and my brother Joe and I used to get under the bed and hide until Mum came back. This went on and on, and that’s why we’ve both got claustrophobia. It was so hard there.”

Michał to Zenona: “But you still remember the bombardments. You said you were on the ground and you were terrified.”

Zenona: “Yes, I was so frightened, because my brother’s twin was killed… I remember Mum laying him out in that room, that bedroom, and dressing him up. He was a little toddler. His name was Adam. And I don’t know when he and my other brother, Joe, were taken to the hospital, but I remember going with my mother to pick Joe up.

“We went by train and I hid under the seat when the conductor came round, because mum didn’t have money. We had a pram. We got off the train in a forest and Mum was pushing this pram, and I asked if I could go in it because I was getting tired, and she said, ‘No, I have to pick up Juzio, and it will fall apart if you go in.’ So I had to trot along by her side. It took ages and ages.”

The twins were born on 29 November 1944. They both developed kwashiorkor, caused by a lack of protein in the diet. It is not clear whether they were taken to hospital before or after the war ended. Joe remained there after Adam died.

Zenona with her mother, Emilia née Szczecina Cyckoma, at the Lebenstedt displaced persons camp in the British zone of defeated Germany.

“My mum did not have it easy, and we hardly saw my dad. There was a forest next to the camp. All the men used to go into this forest, and we wouldn’t see them for weeks. He used to come to see us occasionally, dressed in uniform, like a partisan, and then he’d disappear again. Once he came back and had grown a moustache, and I screamed. I wouldn’t go near him. I was petrified. I said he wasn’t my father.”

The reason Zenona’s father did not feature much in her memories is explained by a December 1946 report by the IRO (International Refugee Organisation), which “recognized [that] … genuine refugees and displaced persons… should be put to useful employment in order to avoid the evil and anti-social consequences of continued idleness…”18

Zenona: “The [new authorities] were also catching prisoners. In the DP camp, we could see them in the basements in one of the other buildings, through the little square windows with bars. I was with another little girl, Wanda. Her mother and another woman gave us food to put under our skirts and we used to walk along those little barred windows, and drop food, so they could get it through the bars.

“I still remember one of them. He was short, dark hair, and I remember the day they hanged him. The bells went, and everybody went out and stood there. All I can remember is someone saying ‘Już go powiesili.’ They have now hanged him. And we never saw that man again.”

Michał: “After the war, a lot of war dirt was coming out, they were finding people, spies, who collaborated, some just to make a fortune, selling out.”

Zenona: “My mum found out that I was dropping food for the men and: ‘Don’t you go near those bars. Don’t you go near that building again.’”

_______________

Zenona, her parents and brother, arrived in Wellington on the IRO-chartered hellenic prince, in October 1950, among just 4,500 displaced persons that New Zealand accepted between 1947 and 1952. The hellenic prince carried 949, mostly from Poland and the Baltic states, and others from Yugoslavia, the Ukraine, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and Russia.

“Mum was pregnant coming over, only just. When we had the medical examination and the doctor realised she was pregnant, she thought we’d never get out. He looked at her and said, ‘Good Kiwi baby.’ He was a nice guy, and let her through.

“They took us to Pahiatua. The Pahiatua children think it’s their camp, but we were there for months too. The Red Cross helped us. They came in a truck with the big red cross on the side of it, and brought us things like clothing and food, sweets, and chocolate—if we got there in time. We stayed in Pahiatua until the government sent us where they wanted us to go. We had no choice.

“While we were at Pahiatua, there was no schooling, no learning the language, no nothing. We were just left there at the mercy of the Red Cross. We slept in dormitories, the women and the children in one, the men in the other. The barracks reminded me of the displaced persons camp.

“Some families got away earlier. Some had to wait. There was a roster again where the mothers cooked. That was organised, but there was no school. We entertained ourselves.

“It was not easy. We were there for quite a while, and then they found us a farm in Ngakuru, which is about an hour’s drive [south] from Rotorua. We were put on a farm, share-milking, milking cows and looking after the farm. It was a real hole, a horrible place.

“We lived in the old cottage and the owner lived in the little sleep-out, a hut almost, one room a bit away from the house. He wasn’t married and didn’t have children, and Mum and Dad worked for him. Mum cleaned for him, did his washing, cooked for him, took him his meals.

“There was a family across the road, a stone, dirt road. The Murrays. They had six sons. Mrs Murray came over to welcome us, brought some cakes, and some other things, but we couldn’t communicate. We didn’t know one word of English. It was the weekend, and she tried to tell us that we had to school go on Monday, go out on the road to the bus. She was showing us ‘bus.’ My brother and I, we didn’t know what she was talking about at first, but Mum sent us out in the morning, and the Murray boys tried talking to us, and helped us get on the bus.

“The bus stopped to pick up some more children, two boys, and when they got on, I thought, ‘Mmmm.’ They were talking in Polish, so I asked:

“‘Where are you from?’

“‘We live over there.’

“‘We live not far down the road.’

“When I got home, I told my mum about them, so the following weekend we walked up the road and introduced ourselves. They were called Maj. Then, Mr and Mrs Murray told us about the Polish man and German lady who lived behind their farm. (Antoni and Ingeborg Borowicz, and their son, Ranier, had also been aboard the hellenic prince.)

“Mum and Dad were over the moon to meet them, because until then we had no one nearby. They were our first Polish contacts in New Zealand after we got out of Pahiatua. They kept in touch all their lives, and if it wasn’t for them, I think Mum and Dad would have been lost. And they would have been lost too, because Ngakuru was somewhere God forgot to go. You couldn’t make anything of that place. There was nothing there, nothing. We stayed there for quite a while and then Dad got a job in Tirau, on a farm again.”

Zenona, Joseph and Richard Cyckoma at the Tirau farm.

“At school at first, my brother and I would sit by ourselves, because we couldn’t talk to anybody, because we didn’t know the language.

“I spoke more German than Polish then, because I went to a kindy in Germany. We didn’t get Polish schooling at the DP camps. I didn’t speak Polish. I spoke German to my parents, because they spoke a lot in German, like everyone in the DP camps. But I knew Polish, just a little bit, just enough to speak to the Maj boys on the bus.

“At school, once I started picking up English, they pushed me from class to class. I didn’t wait a year in one class. As I learnt, they could see what I could do, and they pushed me forward, forward, until I was at the right stage at the right age with my class.”

Zenona at the A&P Show in Tirau circa 1953.

After Józef Cyckoma developed a skin complaint that put an end to his milking cows by hand, the family moved to Tirau proper, where he worked for the council’s roads department. The “big move to Auckland” came when Zenona was 13 and her parents bought a house in Kingsland.

“I still spoke fluent German—I can’t now. Then, when I met Michal, he started talking in Polish, and I had to learn Polish.“

Michał: “She was teaching me English and she was learning Polish. Trouble is, I didn’t learn English properly, and I forgot Polish!”

Zenona: “When we went back home, everyone was astounded that I spoke better than he did. Funnily enough, my brother Joe, who found the English hard, married a Polish woman, and was speaking perfect Polish within six months, because she couldn’t speak English.”

_______________

Zenona was still at school and “sports mad” when she first noticed Michał:

“I used to see him coming on the motorbike. I was such a tomboy, I used to play with all the boys. We lived on a hill in Second Avenue, and we had a trolley and I thought I’m going to go on the trolley and rock that bike off its stand. I never did. We met at the Polish church, and he kept in contact.”

Michał: “A year or two passed, and we started talking and I was spending more time delivering cream and cheese to her Mum… so we started going to the pictures…”

Zenona: “On my 16th birthday, we went to a dance at the Orange Hall off Symonds Street.”

The Pąk-Cyckoma engagement in 1960. On Michał’s right are his parents, Józef and Zofia Pąk and on Zenona’s right are Emilija and Józef Cyckoma.

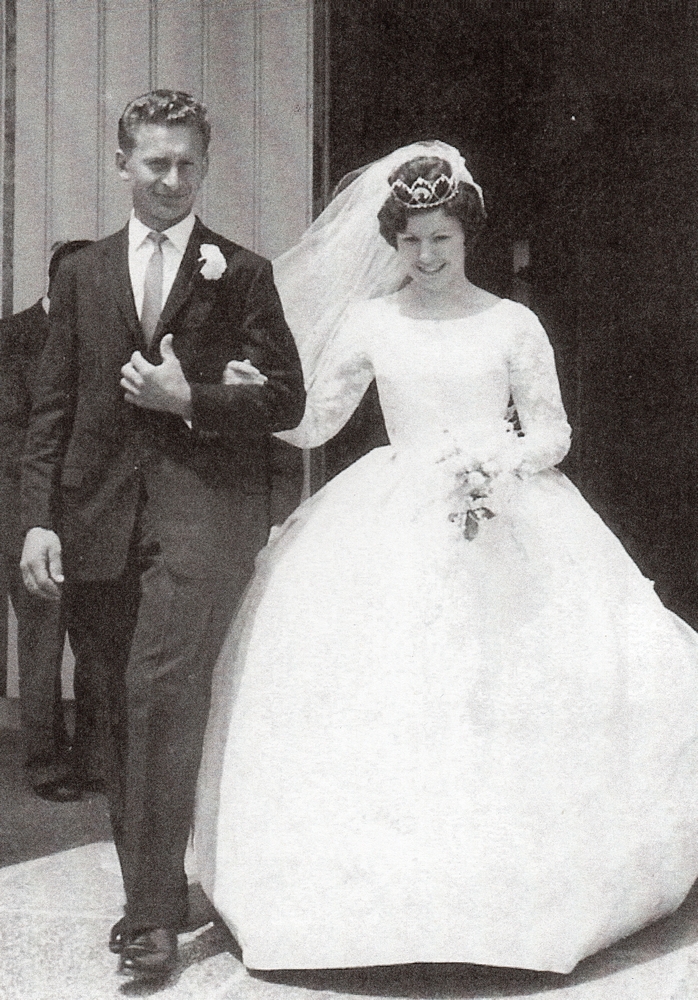

Michał and Zenona married at the St Joseph's Church in Grey Lynn, Auckland, on 3 November 1962, and had two daughters, Regina and Krystyna.

Michał and Zenona’s early life together coincided with the heyday of socials, and organised dances in Auckland, and its growing Polish community, which registered a formal association in 1960, and bought a permanent gathering place in 1963, the same year the couple married.

Zenona: “There was more communication then. Someone would say, ‘My place next weekend.’ Some people didn’t have cars, so someone else would pick them up, or they went by bus. People communicated better, and met up more than they do today.“

At that time in Auckland, many of the Polish veterans who arrived after the war, took up trades. It suited the former farmers who had lost their lands to Stalin, and their sons in the junaki (military cadets) who had been educated in useful future occupations while in the care of the Polish army.

Michał: “There were quite a few of them. Kowalski was an electrician, and Nowacki learnt draughting and went into business, building. Some who didn’t have a lot of knowledge provided work, and learnt like that. Two Polish guys got together and started building houses, and from there, it kept spreading. That’s how I got involved. Nowacki and Neplocha worked together, but Nowacki went to build his own house, so Neplocha didn’t have anyone to help him, and dragged me into building with him.

“I wasn’t interested in building. I said no. I didn’t even go to school in Poland when the woodwork was on. I was working in a textile factory at the time, Holeproof, there were a lot of foreigners working there. Before, I was working in an engineering factory and my wife’s father got me the job with better pay.”

Aleksander Neplocha insisted that Michał would appreciate working in the “fresh air” and convinced the young man to join him.

“I spent 15 years in the building trade and that’s when they started building the Polish house, so we helped as much as we could.”

The old villa bought in Morningside in 1963 through loans and donations became a well-used gathering place. The Poles demolished interior walls and took down the ceilings to create a large dance hall.

Michał: “We didn’t have such a thing as an amplifier, things like that didn’t exist. I remember making up the radiogram, just a machine, some records, the radio, and we danced to it all.

“The socials were bringing money in. More people got involved and more Polish people arrived in Auckland, like my wife’s family, and quite a few Polish people from England came to Auckland and supported [the association], and lent or donated money. We already had the capital on that house, so we when we had a bit more money, we built something bigger.”

Zenona: “More people arrived, and became interested. People then were more eager to be together and accomplish something together. The sierotki [the Pahiatua children] called us depiści [a derivation of displaced].”

Michał: “A lot of other nationalities were coming to our club and mixing with us, Hungarians, Czechoslovakians, Lithuanians. They heard about it, and they joined.

“At work in the factories, foreigners knew each other, and communicated, and half the time it was Kiwi friends that you invited, and that’s how we were making money.”

The new Dom Polski, still existing, was opened in 1973. Its building was a collaborative effort, usually during weekends. Whoever could, helped, whether it was with expertise, experience, or exertion. Mothers and wives had a roster for providing lunches and teas.

These days Michał and Zenona live with among the lifestyle blocks of Oratia, with their daughter Regina and her husband, Piotr. They appreciate the pleasure of the open views without the work of the hectares, and are relaxed with their two dozen chickens and vegetable garden that keeps the cellar pantry in preserves.

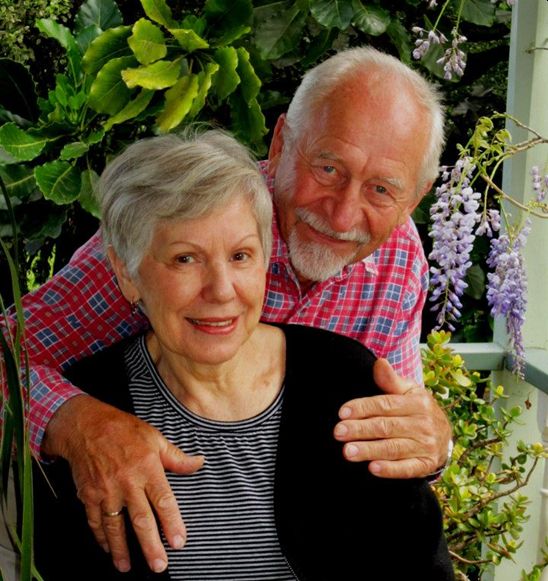

Now married for more than 60 years, Michał and Zenona Pąk in the back garden of their Oratia home.

They may never have put down roots in their native Poland, but their inter-generational life on the outskirts of Auckland reflects the gościnność, the hospitality and generosity, of their shared ancestry.

© Barbara Scrivens, June 2024.

ALL PHOTOGRAPHS COME FROM THE PĄK FAMILY COLLECTION. REGINA WYPYCH TOOK THE LAST ONE.

THANKS TO THE NORTH AUCKLAND RESEARCH CENTRE IN THE TAKAPUNA LIBRARY FOR THE LOAN OF AUDIO RECORDING EQUIPMENT.

ENDNOTES:

- 1- From the translated diaries of Michał Pąk senior, page 210, published as Rycerz Niepokalanej, Knight of our Immaculate Lady, by Wanda & Janek Lis, 2004.

- 2 - Ibid.

- 3 - Ibid, page 221.

- 4 - Aleksander Gurjanow collated records of many of the cattle trains transporting Poles to NKVD forced-labour facilities in the USSR. His work is titled List of Deportee Transports via Rail 1940-1941 by Arrival Station, Karta, 12, 1994.

- 5 - Pąk diary, page 222. (Michał senior did not mention the baby, Korbieta, but she appears with her family on the Karta Indeks Represjonowanych)

- 6 - Ibid, page 225.

- 7 - Michał junior believed the word comes from the Byelorussian language. Jałówka residents living on the border of Byelorussia spoke both languages.

- 8 - Pąk diary, pages 224–225.

- 9 - Karta Indeks Represjonowanych,

https://indeksrepresjonowanych.pl/int/wyszukiwanie/94,Wyszukiwanie.html - 10 - For more on Soviet General Serov’s “Strictly Secret” Order No. 001223, dated 11 October, 1939,

see Missing Humanity,

https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/missing-humanity/ - 11 - General Władysław Anders gives a full explanation on Polish-Soviet relations in the USSR between 1939 and 1942 in his book, An Army in Exile: The Story of the Second Polish Corps, originally published 1949, reprinted 2004 by Battery Press, Tennessee, ISBN: 0-89839-043-5.

- 12 - Pąk diary, pages 291 & 296.

- 13 - In 1945, in accordance with talks and decisions between the USA, Britain and the USSR, Stalin was gifted the entire area east of the so-called Curzon Line. Eastern Poland, half of its post WW1 territory, was absorbed into the USSR.

- 14 - See the story Polish Anchors 1872–1876,

https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/polish-anchors/, and others on the Early Settlers page,

https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/early-settlers/ - 15 - Pąk diary, page 314.

- 16 - Commander Wojciech Francki was born in 1903 and was awarded the Polish Cross of Valour four times, the first as

a teenager for his courage during the 1919-1920 Polish-Soviet War. After a distinguished career in the Polish Navy during

WW2, he moved to New Zealand with his family following an offer of employment. Despite finding out that he had been misled,

he remained in New Zealand but, after his children were educated and left New Zealand, he and his wife moved to Australia

where he again pursued a career at sea.

https://www.navyhistory.org.au/commander-wojceich-franki-polish-navy-rtd/ - 17 - United Nations archives,

https://search.archives.un.org/uploads/r/united-nations-archives/7/2/8/728eed48ecc7b9ae115e06ec1e9016d1f8a28218adaa7a5540e9bf70085bd4e3/S-1301-0000-2344-00001.PDF Pages on the pdf do not correspond to the pages of the reports. Pdf pages 2 & 29, report page 1. - 18 - From the preamble of the IRO constitution, 15 December 1946.