MISSING HUMANITY

by Barbara Scrivens

“Locked in the car, hungry and bugs biting us without mercy.”

I translated my father’s original Polish words nine years after he died. His 1942 schoolboy essay described how Soviets invaded his country and banished his family to Siberia. I recognised his swirls and strokes, already inherent at 14. The three and a half pages became the longest—the only—conversation he had with me.

He described his family’s 18-day cattle train journey from Niweck in eastern Poland to Tiesowaja, a Soviet NKVD forced-labour facility a few degrees south of the Arctic Circle. The NKVD, translated from Russian as the “People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs,” or secret police, was the precursor to the KGB.

The “car” was a poorly lit wagon previously used for carrying cattle. In Russia they were “adapted to the use of passengers by the simple addition of planks and… stoves: and by the opening of a largish round hole in the floor which is intended for the passing of excrement.”1

I translated “bugs” from “pluskwy,” which lived in raw wood. Judging from others’ recollections, these tenacious insects would have continued to plague him.2

My father, Zdzisław Nieścior, titled the essay he wrote two years after that journey “Osierocony Polak.” A direct translation is “An Orphaned Pole”—but he was not an orphan. As far as he knew, his father was in the Polish army, his mother and two of his younger brothers were in a Polish refugee camp in Persia, and his younger sister and baby brother still with his maternal grandmother and extended family in Poland. Without his parents and siblings, though, and so far removed from his beloved home, he may have felt deserted, and so “An Abandoned Pole” or even “A Bereft Pole” may be more fitting translations.

He could not then fathom the reasoning behind the Soviet invasion of Poland… his family’s abduction… or their incarceration.

The Junackie Szkoły Mechaniczne (Military Cadet Mechanical Schools) in then-Palestine became my father’s guardians between 1942 and 1947. The Polish army organised several similar cadet schools to cater for the many hundreds of Polish teenagers too young to enlist but who still needed care and education.3

The Polish army organised a Documentation Office in 1942 to obtain statements from Poles who arrived from Soviet prisons and forced-labour ‘camps.’4 The Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace library at Stanford University, California, archived my father’s essay and hundreds of others written by the junaki. It also stores a deposition and a completed questionnaire from my paternal grandfather, Stanisław.5

My father’s words reverberate with incomprehension and indignation. He could not then fathom the reasoning behind the Soviet invasion of Poland on 17 September 1939, his family’s abduction at the hands of Soviet soldiers five months later, the manner of their removal to Tiesowaja, or their incarceration.

_______________

Before Hitler’s trains carried Jewish families to Nazi concentration camps in German-occupied western Poland, Stalin’s trains carried Polish families from Soviet-occupied eastern Poland to NKVD forced-labour camps in the far reaches of the Soviet Union. Four mass forced-expulsions of Polish families are included in the estimated 1.7 million Poles who disappeared between September 1939 and June 1941. They became dispensable cogs absorbed by Stalin’s Five-Year plans. They worked on a labour-for-bread basis in the hundreds of NKVD-run prisons, gulags and forced-labour facilities, set up to fulfil Stalin’s ambition for Soviet expansion.

The Poles’ plight reflected the USSR leader’s hatred of the Polish nation and his intention to eradicate it.

The incarcerated were meant to labour until they died. The guards repeatedly told my paternal grandfather that he would never see Poland again. The guards were correct—but not because he died labouring in the frozen forests of Soviet Russia. He survived that, and went on to fight in the Second Polish Corps, surviving that too. Stanisław Nieścior died in Italy, aged 49, a year after the war in Europe ended, and knowing his Poland was indeed lost to the Soviets.

Similar expulsions to the USSR… brought the total number of Polish civilians removed from their homes to an estimated 990,000.

In the early hours of 10 February 1940 Russian soldiers and their Ukrainian henchmen woke an estimated 200,000 Poles living in Soviet-occupied eastern Poland and delivered them at gunpoint to the cattle trains. It was the first and smallest of the mass transports. Similar expulsions to the USSR in April and June 1940 and June 1941 brought the total number of Polish civilians removed from their homes to an estimated 990,000.

Numbers per transport varied according to the trains available and how many Poles the Soviet soldiers managed to pack into each wagon.

The first group included whole villages of farmers, farm labourers, forestry workers, former soldiers who had received grants of land, civil servants, local government officials and members of the police forces.

The NKVD identified Stanisław Nieścior as a former soldier. He had received a grant of land from the new post-World War I Polish government after volunteering for the Polish army in 1919 and taking part in defeating the Bolsheviks attacking Lwów and other eastern boundaries. He later received 32 hectares in Niweck, in Wołyń province. The nearest train station was in Sarny.

My father wrote:

“They surrounded our house from all sides and the rest of the soldiers entered our house… They first searched Tato (Dad) and while two soldiers with rifles guarded him Mama was ordered to pack. She asked one of them where we were going to be transported and he answered: ‘To another oblast (area)’… They packed our belongings on a cart, although five carts would not have been enough. In the evening we arrived at the station and were put into wagons.”

In his deposition my grandfather said the soldiers arrived at 6am and gave them 50 minutes to pack.

When my mother, Kazimiera (née Surowiec), first told me her family was “taken by cattle trucks to Siberia” I did not know then that my father had gone through the same experience at the same time. I was a teenager and not as incensed about the journey as the fact that her family was arbitrarily kidnapped and sent somewhere they did not want to go. Cattle trucks? I envisaged container wagons fashioned with wooden benches, where the hapless sat gazing out of windows as they went farther and farther into unknown territory.

My mother does not remember much of the journey that started only three days after her sixth birthday. Her father, also a farmer, moved his family in 1938 from Bratkowice near Rzeszów to Śmigłowo, a purpose-built civilian settlement of one road and 50 houses a few kilometres north of Zaleszczyki, on Poland’s then-southern border with Romania. Compared to the thin, sandy soils of Bratkowice, where he and his wife, Karolina, were born, the dark loam of his new property offered a brighter future for their young family.

Born in 1908, and 11 years younger than Stanisław, Władysław Surowiec had no military connection, no political office and was not in the least bit wealthy. My mother remembers her parents spending their days planting and tending grape vines. The only reason I can find for their forced-removal was being Polish in Śmigłowo.

My perception of the train journeys changed when I started researching the history of what was euphemistically termed the two families’ “deportations.” I began to understand the extent of the Soviets’ monstrous wickedness when I read the the dark side of the moon.

_______________

Polish President General Władysław Sikorski commissioned the book shortly before he died in a suspicious aircraft accident off the coast of Gibraltar on 4 July 1943. His widow, Helena Sikorska, verified her husband’s confidence in the writer, Zoë Zajdlerowa, an Irish woman married to a Pole and living in Poland at the time of the 1939 Soviet invasion. Zajdlerowa remained anonymous at the book’s 1946 launch—for her and her family’s safety.

“That this book should be preserved and meditated upon by posterity is certainly to be desired.”—TS Elliot.

Mrs Sikorska said her husband “knew the author for a woman of scrupulous integrity and fairness” and that he had left instructions for Zajdlerowa to “be given access to official material and documents.” TS Elliot wrote in the preface: “That this book should be preserved and meditated upon by posterity is certainly to be desired.”

Zajdlerowa examined the official records held by the Polish government-in-exile, then headquartered in London, and informal written recollections like those of my father and grandfather. She found the Soviet occupiers’ instructions detailing the expulsion method—organised in minute detail and signed by General Ivan Serov, Deputy People’s Commissar of Public Security of the USSR.

People arrested within the first few hours of the Soviet occupation in 1939 included representatives of all political parties, leaders of all trade unions, town councillors, civil servants, skilled workers, barristers and engineers.

“All this, however, was still too little” and led to a secret registration of people “to be deported to Soviet territory by a series of mass deportations, and to be there confined within Soviet penal institutions.”6

In the “Strictly Secret” Order No. 001223, dated 11 October, 1939, General Serov made it clear that the “deportation of anti-Soviet elements from the Baltic Republics is a task of great political importance.”7

Such “anti-Soviet elements,” according to subsequent NKVD Order No. 0054:

… must embrace all persons who, by reason of their social and political background, national-chauvinistic and religious convictions, and moral and political instability, are opposed to the socialist order and thus might be used for anti-Soviet purposes by the intelligence services of foreign countries by counter-revolutionary centres.

These “anti-Soviet elements” automatically included the identified person’s family.8

Serov noted in his decree that the “successful execution” of the “deportations” depended on the various districts’ Soviet-appointed operative troikas “carefully working out a plan for executing the operations and for anticipating everything indispensable.” The procedure needed to be carried out:

… without disturbance or panic, so as not to permit any demonstrations and other troubles not only on the part of those to be deported, but also on the part of a certain section of the surrounding countryside hostile to the Soviet administration.

Serov's 10 pages of instructions included:

- “On principle, the whole operation shall be carried out by the above-mentioned

Executive Troikas at night-time.”

- “The deportees may be allowed 20 to 60 minutes for packing their things.”

- The weight of baggage of any family was not to exceed 100kg and could contain only clothing, bedding, kitchen utensils,

food for a month and fishing tackle.

- Farmers were allowed to take certain farming implements, to be loaded onto separate trucks to prevent their use as

weapons.

- Crowds were prevented: “When the column of the deportees is passing through inhabited places or when encountering

passers-by, the convoy must be controlled with particular care; those in charge must see that no attempts are made to escape,

and no conversation of any kind shall be permitted between the deportees and passers-by.”

- Trains were to be ready for departure before dawn.

- Heads of families were to be segregated and put in special cars.

- After “entrainment,” the doors and windows of cars were to be blocked up, leaving only an opening “for

the introduction of food and the elimination of excreta.”

Soviets like Serov referred to the Poles whom they were shortly to exile as “deportees.” This ruse created a false judgement of criminality on the Poles. Countries deport people if they have entered illegally or if they have taken part in an unlawful act, been tried, found guilty and expelled from the country they had entered. Deportation means expulsion of an undesirable alien.

The Poles gathered up in the mass kidnappings and forced-removals of 1940 and 1941 were not law-breakers. They were ordinary citizens, finally living in their own country after 146 years of partial, and 123 years of total, partitioning by Russia, Prussia and Austro-Hungary. In post-World War I the newly freed worked hard to build their new Polish republic. Those in eastern Poland turned wasteland into profitable farms.

It is no wonder my father struggled to comprehend.

_______________

Unknown to those soon to be taken away, the Soviets completed arrangements for the first mass forced-removal of Polish civilians shortly after New Year 1940.

Trains, commissioned from all over the Soviet Union to move the human cargo, made their way west and assembled in Poland. By February 1940 an estimated 110 stood ready.

How did the Poles not notice the dark green metal-roofed snakes that, away from railway platforms, were “extraordinarily high… always coiling away somewhere and always partly lost to sight”? Each of the trains that slunk into Poland from the east had “hundreds” of windowless wagons, double doors opening in the middle and secured on the outside by an iron bar. Once the doors closed the only light and fresh air entered through two thin, grated slits under the curved roofs.9

The trains escaped detection that winter in large part thanks to the disintegration of the Polish countryside after the Soviet invasion the previous September.

The soldiers found the two [hogs] she hid… All she could buy from the co-operative the next day was four boxes of matches and half a litre of kerosene.

Soon after, my father in Niweck noticed the soldiers: “first bought shoe soles, because they were difficult to obtain in Russia, then dress fabric and consumer goods, and after three weeks nothing could be bought in the shops for lack of goods.”

Two weeks later the Soviet soldiers “… started to remove: wheels from carriages, furniture, they even tore out floors and carted it all East. In town the queues for bread, and in the village for salt and paraffin, were unbelievable. Other goods such as soap, paper, exercise books, sugar, sweets, buns, shoe re-soles, and other goods were utterly impossible to obtain.”

My father recalled how his mother tried to convince Soviet soldiers that their farm had no hogs. The soldiers found the two animals she hid and bullied her into selling them for 300 roubles. All she could buy from the co-operative the next day was four boxes of matches and half a litre of kerosene.

The invasion of Poland coincided with harvest time. Fields needed cutting, fruit trees hung low and farmers’ wives would normally start pickling and preserving food for the winter.

The Soviets had instructions to seize all goods in Poland and transport them to the USSR. This included crops such as grain and tobacco, timber, coal, pig-iron, cement, drugs, textiles, apparatus from laboratories and clinics, furniture and building material such as doors, frames, window sashes and floor planks. The resulting lack of raw materials led to the closure of 67,000 small Polish workshops and their skilled artisans losing employment. Of the 8,500 shops in Lwów, for instance, the Soviets stripped and closed 6,500. Polish factory personnel and their families received orders to accompany the removed plant to the Soviet Union.10

And so the Soviet occupiers “nationalised” Polish commerce.

Harvests rotted in fields, and fruit beneath trees. Soviet soldiers slaughtered breeding stock and trampled and burned haystacks. Zajdlerowa noted:

The whole infinitely costly storehouse of generations had been burst open and destroyed; and not even from any imagined military necessity but from a profound contempt for the care and toil of the individual and for the mystery of man’s long husbandry of the soil…11

Within the disquiet created by the invasion and occupation, the trains that crept in become part of the detritus of abandoned railway sidings, hiding in full sight in the growing unfamiliarity of the Polish landscape.

Zajdlerowa:

Into this scene—in which everything now spoke of decay and ruin—the idle railway cars, the cold locomotives, the snow piling up under and against the wheels, the uncleared lines and the motionless signals, fitted so well as to be perfectly invisible.12

_______________

Europe’s 1939-1940 winter was particularly harsh. On 10 February, a Saturday, it was snowing in eastern Poland and weather stations recorded 35 degrees of frost. Those rifle butts banging on their doors in the dark caught the first unprepared families completely by surprise.

They were taken to railway stations on horse-drawn sleighs, carts and armoured cars, heavily guarded by Soviet soldiers with rifles and fixed bayonets.

“Confusion” became the most repeated noun in witnesses’ and deportees’ accounts.

Some of the wagons in the February transport had primitive stoves but no fuel. Often the stoves had their sides driven in. The few planks arranged in tiers around the walls were never enough to accommodate the average 50 to 60 people crammed into each boxcar. There was no bedding provided and some cars had no bunks. The extreme filth on the walls and floors made Zajdlerowa believe that humans had previously used them. Transport for the Soviet army when it invaded Poland?

The actual condition of the trains made a mockery of that part of Order No. 001223, stating that on the “day of entrainment” three high-ranking officials would examine the railway cars “to see that they are supplied with everything necessary.” Perhaps the chief of the entrainment point, the chief of the deportation train and the chief of the convoying military forces of the People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs (named by Serov as overseers) were not looking to basic hygiene, or humanity. More likely, Serov’s instructions were documented for show, and not on the expectation they be carried out.

From the first-hand accounts that Zajdlerowa read, for instance, Soviet soldiers seldom ahdered to Serov’s directive for 25 people to a car.

Trains, after being loaded, often stood for days before leaving and the tracks along which they stood became piled with excrement, and yellow and boggy with urine.

“Confusion” became the most repeated noun in witnesses’ and deportees’ accounts.

Zajdlerowa stressed that every separate piece of evidence she used in her book came from first-hand recollections:

… Old and dying, in their ghastly bed-linen, just as they had been dragged out of bed, collapsed in heaps on the ground.

… The stations rang with the cries and groans and names being desperately shouted above

the din. Above everything was heard the ceaseless shouting out of names, and cries of ‘I am here,’ ‘Come to

me here,’ ‘Now, now, I am being dragged away.’

… Old and dying, in their ghastly bed-linen, just as they had been dragged out of bed, collapsed in heaps on the

ground.

… Corpses of children froze in the snow and their mothers, vainly trying to restore them to life, covered them with

their own bodies and felt the same deathly chill creep up their own limbs and touch their own hearts.

… There were people who went out of their minds from horror and shock and their lamentable complaining was added to

all the other fearful sounds of woe.13

Although they did not know it at the time, those who managed to pack—and hang on to—their baggage had the best chance of survival. In the mayhem many people lost their families and their bundles. Some of those arrested away from their homes did not get the chance to pack at all. Baggage piled up at the railway stations was “flung around.” Each person had to carry their own. Small children and pregnant women stumbled under the weight.

Relatives, neighbours and friends returned repeatedly attempting to deliver food, tobacco or some “scribbled words on a scrap of paper” to those locked in the trains. Occasionally, the guarding soldiers allowed the still ‘free’ Poles through the cordons. The soldiers:

… were not often humane, but they were not often deliberately cruel either: not yet… They were simply indifferent, carrying out their own orders, accustomed to such work, possibly even a little taken aback by the intense grief and horror shown by the Poles.

A footnote on the same page:

The Soviet soldier, in strong contrast to this [show of emotion from the Poles], having no experience of and no information as to the freedom of an individual, and no conception of such a point of view, could not understand why the Poles were making such a fuss.14

Often the guards promised the crowds of visitors clamouring at the trains that they would be allowed through at an arranged future time. When they returned the train, which had sometimes been standing for days, had disappeared.

The train driver “gave no consideration” to the terrifying effect [of] his “terrific speed which rarely slackened”…

Once the wagon doors closed, the people inside herded together, already suffering from shock at their circumstances, grieving at their losses and a sense of unreality. Many had not eaten for days. Parents attempted to distract their children, some of whom screamed and wept, more at first from cold and fright than from hunger. Family members supported one another. By common consent, the very old and frail, mothers with young children and pregnant women were given the most space. Where possible, people found something to screen the hole in the floor but this impression of privacy “… was seldom practicable. People simply tacitly agreed that they did not see each other. In fact, it was impossible to keep on being sensitive.”15

The trains travelled slowly through Soviet-occupied Poland, following Serov’s instructions for the convoy being “controlled with particular care” when “passing through inhabited places or when encountering passers-by.” This changed dramatically on crossing the Russian border. The train driver then “gave no consideration” to the terrifying effect that his “terrific speed which rarely slackened” would have on the occupants thrown about inside the wagons.16

Zajdlerowa read accounts of how the most self-controlled people gave way to hysteria; some children became so petrified that they stiffened themselves on the highest bunks and refused to come down.

Arrangements on the trains varied. There was no regular allowance of food and drink. On most trains Soviet soldiers handed out sour, black, badly-baked bread every two to three days. “Perhaps once or twice” they distributed a few buckets of fish soup with fish heads and bones or eyes and entrails of animals. Some convoys received no food at all—but hunger was not the worst hardship, as many families had taken food with them.

It was thirst that plagued those imprisoned in the airless, rolling wagons.

On no train, at any time, in any temperature, was there ever anything like the lowest

possible amount of water which could keep a human being from suffering acutely from thirst…

There were whole days of twenty-four hours when not a drop to drink was passed into the cars. There were periods even of

thirty-six hours. The allowance, when it did come, would be a bucketful, sometimes two, never more, for a whole car. Even

when snow lay deep on the ground and on the roofs of the trains, and could have been scooped up in buckets and passed in

without the slightest trouble, they could not be bothered to do it. People went out of their minds from this suffering.

Little children could no longer force even a cry from their swollen throats.

… The callousness shown by the soldiers on convoy to all the desperate appeals made for water is more difficult to

understand than anything else. … when not in danger … of being deprived of it himself, persistently to refuse

to hand in a bucket of water to fifty or sixty human beings, shut in together under such conditions. It is a fact that these

men did refuse to do so, and could keep up this attitude throughout journeys lasting four, five and six

weeks.17

Water became more of an issue for the following three mass expulsions, two of them in the extremes of summer. Dust from sand storms easily penetrated the slits in the wooden boxcars and the metal components became burning hot.

Tongues turned black and stiff and protruded from ghastly mouths and throats. To all entreaties, soldiers returned only curses or blows. Corpses were thrown out onto the line or put out at rare stopping places. Once or twice, some merciful rain fell.18

The number of soldiers in a convoy varied. Usually a soldier, allocated to each car, sat outside on a small platform. The last car of each convoy always carried a mounted machine gun. At night, searchlights lit the roofs. Every few hours, prisoners braced themselves for an ‘inspection:’

… the soldiers moved up and down the train, stepping on prostrate bodies,

thrusting others out of the way… beating on the walls of the cars with their rifles to make sure no planks had been

loosened anywhere and nobody was contemplating escape… The noise alone was torture. The manner of the soldiers was

violently overbearing and rough.

The reader can be given facts. He cannot share the experience. He can read about the filth, but he cannot taste it in his

throat and feel himself saturated by it, as these people did… One can enumerate the horrors. The lack of privacy. The

thirst and hunger. The accumulated anguish of body and mind. The fatigue. The epidemics. The sores. The vomiting. The

diarrhoea, digestive troubles, dysentery and bleeding. For women, menstruation, too, and childbirth…

The convulsions of those, most advanced in age, who simply could not bring themselves to make use of the opening in the

floor, and who strained their bowels to the point of violent rupture. The fevered and broken sleep. The appalling dreams. The

nostalgia. The roughness of the soldiers. The agony of mothers over their children… and before the fear of final

separation which never left any of them for an instant.19

My mother’s vague recollections of the train journey bears out Zajdlerowa’s finding that younger children adapted more easily to their plight. I have no doubt that adults would have done their best to shield and distract them from what was happening.

“The old, without exception, suffered most in every way.” They and the youngest died first. For the old:

… the whole endless torturing business of the body’s needs, and the absolute

lack of any decency or privacy in which these needs could be satisfied, pressed with accumulating cruelty not only on the

poor body, but also on the mind… 20

… They felt themselves to be a terrible burden on the young and the strong… More and more people lay on the

floor too weak or too ill to stir. But the elderly and the old never made this compromise. They could not: just as their

bodies, which had been cleanly and decently nourished all their lives, could not digest the food. Infants, whose stomachs

were still adaptable, digested it and wanted more.21

Sometimes the journeys involved changing trains. Guards marched some groups through streets to a clearing centre or another station. People who could not keep walking under the weight of their bundles threw them away for fear of being shot by the guards, who apparently became most savage during the last transportation.

The journeys generally ended on lorries, sleighs or on foot, depending on what part of the USSR they were in, the season and the state of the roads or, more often, tracks. The forced-labour facilities were 30 to more than 100 kilometres away from the main railway lines. Many reported they had to stumble on foot across deserts. Others had to cut their own way through forests or cross mosquito-infested swamps.

_______________

The Soviet machine expanded on the Tsarist habit of sending alleged dissidents to “exile” in remote USSR. Back in 1878 New Zealanders read how:

A Catholic priest at Warsaw has been sent to Siberia for a curious offence. As was his duty, he read the Czar’s declaration of war to his flock, and, not being able to speak Russian, read it in Polish. This was against the law and hence his transportation.22

Two years earlier the Catholic periodical new zealand tablet described the plight of:

Polish priests who are scattered in banishment all over Siberia, and the inhumane treatment to which they are exposed… The number… amounted not long since to 400. Of these fully 100 have succumbed to the rigours of their martyrdom. The lot of the exiles lies completely in the hands of the governor-general and his subordinates… Most of [the priests] are without any means of subsistence at all. Petitions to the Government are forbidden under severe penalties, and if, in spite of the prohibition, memorials find their way to the governor-general, their only result is to insure additional rigorous treatment for the memorialists.23

The inclusion of whole families in 1940 forced the Soviet machine to funnel the current Polish “nonconformists” into slightly modified institutions. Forced-labour “deportation” facilities for families were added to the hard-labour “corrective” gulags already existing in the USSR.

“Lagiers exist throughout the whole of Soviet territory, and are solely, and absolutely, within the control of the political police…”

In their documentation, the Soviets used the words “deported” and “exiled” in subsequent lines for an entry recording the same person. They also used the oxymoron “free exile” to differentiate the families in these particular transports from those Poles arrested at other times and sent to hard-labour facilities called lagiery.

Zajdlerowa explained in 1946: “Lagiers exist throughout the whole of Soviet territory, and are solely, and absolutely, within the control of the political police… known as the NKVD.”

Regarding the family groups: “The deportees are put to much the same type of pioneer work as is done in lagiers, but are paid for their labour on a system of piece-work and buy their own food in shops owned and kept for this purpose by the NKVD.”24

Work in the family facilities, dotted about a kilometre apart along main transport lines, revolved chiefly around supplying the raw materials for building roads, railway lines and canals. They tended to be in forest outposts close enough to the new transport networks to be able to provide this raw material.

These family prisoner-labourers could count themselves lucky—they were more likely to survive than those sent to lagiery deep in Soviet “special territory” where they were put to work in the gold mines. At Kolyma, for example, released prisoners reported, “… you can eat gold with a spoon.” Only 583 of the 100,000 Poles imprisoned in Kolyma survived to relate such tales. General Władysław Anders, in his book an army in exile, dedicated a chapter to Kolyma Means Death.25

My mother’s family was held in Taishet, near Irkutsk and Lake Baikal, north of the Mongolian-USSR border. She called it a posiołek. This is a direct translation of the Russian word “posiolok” meaning “settlement” or “osada,” the same word generally used to describe the farms in eastern Poland.

The two could not be more dissimilar. Before—and after—the Poles’ incarceration in Taishet, the NKVD recorded the facility as a “gulag.” It is unlikely that its structure changed to any great extent while the Polish families were detained there in 1940 and 1941.

_______________

The lack of humanity on the part of the Soviet soldiers is partly explained by the beliefs of the founders of the Soviet social system, the Bolshevik Party. Under Vladimir Lenin’s leadership, the Bolsheviks assumed power after the 1917 Russian Revolution and the downfall of the Tsarist Empire. Lenin followed the communist writings of Karl Marx. The Bolshevik Party morphed first into the Russian Bolshevik Communist Party then into the Communist Party. Lenin became the first Soviet head of state.

While the Russian Tsars had directed their lives to empire-building and the accumulation of their own wealth through trade, their successors:

… had bound themselves to the accomplishment of something infinitely more

difficult… it was their intention not to take out but to bring in, however much it might be disguised as

machinery… a new ethical conception… a new moral code and a new system of laws.26

… the heretic everywhere was the individual, the man who preferred his own way of life, however limited, however

insecure, because it was his own; worst of all, who preferred his own way of thinking. This individual everywhere had to be

subdued, and if he could not be subdued, exterminated.27

This subjugation included the “pacification” and “liquidation” of entire republics, and farming and nomadic societies. Of the 175 million people living in the Soviet Union at the time, 80 to 90 percent were illiterate and led primitive lives. They retained the legal status given to them by the Tsars—identical to that of pigs and goats.

“… Any group or section of society or racial block may find itself marked out for segregation, and, following a certain rhythm, for eventual liquidation.”

The majority of these people greeted the new Communist Party ideal with ignorance, apathy and obstruction.

The Party became more militant, its members “convinced that they alone in the universe are the depositories of absolute truth.”28 It prepared to compete with ‘enemies abroad’ by building up heavy industry and armaments. It dealt with ‘enemies within’ though propaganda, recurrent purges and trials, and continued suppression of any kind of freedom of thought. The purges increased after Lenin’s death in 1924.

The “corrective” and “deportation” facilities expanded within this system of increasing governmental control. The welfare not of the individual, but of the community, became the Party’s sole standard of morality and, consequently, of justice. Behaviour was assessed and rewards and punishment distributed accordingly:

… Should the State (in the person of the Party) consider that it has been, even

accidentally, prejudiced, or even criticized, by word or deed, then the individual responsible has not only legally but also

morally offended, and a penalty has to be paid: the penalty being segregation from the community, in one form or other.

… Any group or section of society or racial block may find itself marked out for segregation, and, following a certain

rhythm, for eventual liquidation.29

The Soviet soldier born within this regime became the Soviet robot who in 1940 and 1941 had no understanding, compassion or empathy for his own brothers, sisters, mother, father, wife or children, much less a group of ‘rich’ Polish strangers expressing emotions he could not understand.

_______________

Hitler temporarily stopped Stalin’s systemic removal of Poles to the USSR. On 22 June 1941, the German army crossed the German-Russian division of Poland, their sights on Moscow.

As German forces swept through Soviet-occupied Poland and into Russia in June and July 1941, more than 300,000 Polish citizens were in the same cattle trains as in February 1940 and hurtling towards the USSR interior.

In 1994 Aleksander Gurjanow, again using the misleading Soviet term for the Poles, compiled a partial list of “Deportee Transports by Rail 1940-1941” from records available from the KARTA Centre Foundation (Fundacja Ośrodka KARTA).30

The Polish Prime Minister did not quibble—he saw a way to free his compatriots.

According to Gurjanow’s list, Soviet soldiers started rounding up what would be the fourth and last mass transport of civilians from Poland on 5 May 1941. The last trains left on 21 June 1941, which suggests Hitler's invasion surprised Stalin. Some of the last railway transports did not make it past Kazakhstan, as the Soviet army’s need for the trains took preference over taking the Poles to their designated destinations. (The forced removals continued in 1945, once Stalin again had control of Poland, and only stopped a few years after he died in 1953.)

It took Hitler’s proximity to Moscow for Stalin to appreciate the potential of using the Poles on his territory as soldiers fighting a common enemy. The Soviet leader ingratiated himself with the Allies and re-established Polish-Soviet diplomatic relations. On 30 July 1941 Polish Prime Minister Władysław Sikorski and Soviet ambassador in London Ivan Mayski signed an agreement that granted the incarcerated Poles ‘amnesty.’

The word “amnesty” again suggests these Poles were criminals deserving their sentences. It indicates a false magnanimity on Stalin’s part. ‘Amnesty’ in this story and others is qualified with inverted commas to point out the flaw and irony of the Soviet term. The Polish Prime Minister did not quibble—he saw a way to free his compatriots.

A Polish army was to be formed on Russian soil. The future Polish Commander-in-Chief of the Polish forces in the USSR and future Commander of the Second Polish Corps in Italy, General Władysław Anders, walked out of Moscow’s Lubyanka prison.

The Polish army first gathered in Buzuluk, southern Russia. Later the Russians allowed the Polish army headquarters to move south to the kinder climate of Tashkent in Uzbekistan.

Regardless of the ‘amnesty’ the Poles—especially those with families—had to make decisions before another winter made travelling impossible.

The news regarding the army filtered slowly to the Poles in the forced-labour facilities. Thanks to Stalin’s Five-Year plans and quota systems it was not in the NKVD managing commanders’ interests to lose their labour forces, so some chose not to relay the information. Some inmates did not believe the rumours. Poles with access to newspapers and radios helped spread the word. Some camp commanders offered the Poles better wages and living conditions if they stayed.

The camp commander at Tiesowaja in Archangelsk told my paternal grandfather he had “run out of” the release certificates needed to show that the holder and his family were travelling legitimately within the Soviet Union. Stanisław Nieścior—literate in Russian—made the decision to leave without one.

Poles left their NKVD captors. Their isolation had made gates unnecessary. In such remote areas, where would inmates have gone? Regardless of the ‘amnesty’ the Poles—especially those with families—had to make decisions before another winter made travelling impossible. They knew how long it had taken them to get to there, and knew they faced arduous journeys of sometimes several thousand kilometres. They had to consider the chances of weaker family members surviving the trip compared to surviving another Siberian winter.

With the knowledge they may not find shelter, and faced the probability of lack of food and water, the Poles left on foot, with hand-pulled carts or on rafts down rivers, and made their way to the same railway stations they had passed through nearly two years previously. The Poles desperate to leave waited sometimes for weeks for a place on trains still attending primarily to a country at war.

My father’s family travelled south; my mother’s went west. No callous Soviet soldiers dogged those journeys, but the time in the labour camps had taken its toll. I know it had been especially hard for those families who spent the longest time under the bread-for-labour regime, and for those with young children, like my mother’s. My father was able to help his parents in the forest. Three Nieścior workers shared their rations among five but my Surowiec grandparents had four children between two and eight years old in 1940—children unable to work but who still needed feeding.

Many emaciated, disease-ridden bodies finally ran out of life before reaching the much-anticipated destination. Two were my mother’s little sister and a family friend’s week-old baby girl.

They died days apart on the way to Tashkent in Uzbekistan and were buried together in the sand at the side of a road. Whether there is anything left of their remains is doubtful. They—like so many others—did not have the dignity of resting in peace in a cemetery.

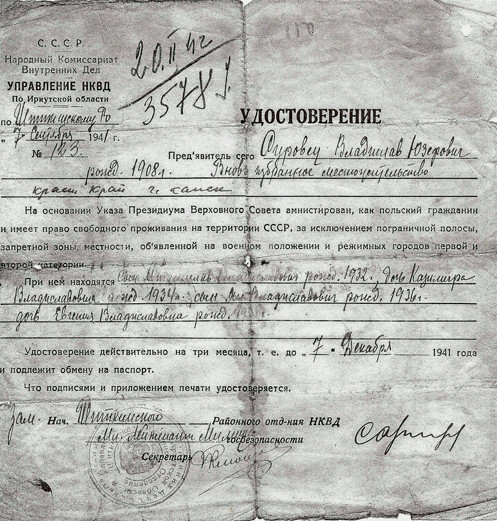

Remembering that time triggered a deep chill in my mother so I did not pursue her for details. I cherish the copy I have of the NKVD release certificate Władysław Surowiec received.31 The folds and water-damage just miss the last name on the list of his children. It is the only record I have that Eugenia Surowiec, born in 1938, ever existed.

_______________

Figures can be manipulated and are always open to interpretation. After war, both sides exaggerate and understate their losses, depending on what kind of image they want to convey. How can one decide which is the greater loss—the USSR’s 8,868,000 military casualties in Europe from a population of about 191,000.000 in 1940, or nearly 12,000 New Zealanders when the total population was then 1,400,000?

Warsaw tops the list of principal bombing targets… Estimated civilian deaths, 1939-1944… totalled 90,000.

New Zealand’s figures come from the Commonwealth War Graves Commission and more reputable to me than those from the USSR, where the 1937 census results were destroyed, and its organisers sent to gulags.32

Warsaw tops the list of principal bombing targets in Norman Davies’ europe at war: 1939-1945, no simple victory. Estimated civilian deaths, 1939-1944, in Poland’s capital city totalled 90,000. Berlin is second, with 49,000 during 1940-1945, and London third with 43,000 during 1940-1941.33

The USSR tops Davies’ list of military deaths in Europe, 1939-1945, (the 8,868,000 above). Regarding military deaths (300,000), Poland shares fourth spot with Romania and Yugoslavia. 34

Between counts taken in 1939 and 1940, Poland lost nearly 8,000,000 citizens—from nearly 35,000,000 in 1939 to nearly 27,000,000. By 1945 a further 2,000,000 vanished from statistics.35 Not all died, but they no longer lived in Poland.

I have a good idea what happened to 1,700,000 of those 10,000,000.

Nearly a million are represented in this story. The balance included Polish prisoners of war who fought on both fronts in 1939, Poles conscripted into the Soviet army, and at least 250,000 Poles classed by the Soviets as political enemies.36

More than 22,000 were officers murdered by the NKVD—buried in mass graves in western Russia. A further estimated 4,500 were shot after the 1941 Russian-German war. At least 110,000 “disappeared without trace.”37

Of the 990,000 Polish citizens seized and sent by the Soviets to forced-labour facilities, more than 400,000 were thought to have died of ‘natural causes,’ and more than 300,000 from cold and exhaustion within the facilities. Many of those who did not die remained in the Soviet Union, dispersed around the same prisons, forced-labour facilities and other factory towns.38 Despite the war, Stalin’s Five-Year plans ground on. Many Poles slipped through the statistics after Soviet citizenship was forced on them, and assimilated into Soviet society, including orphaned children who knew no better.

_______________

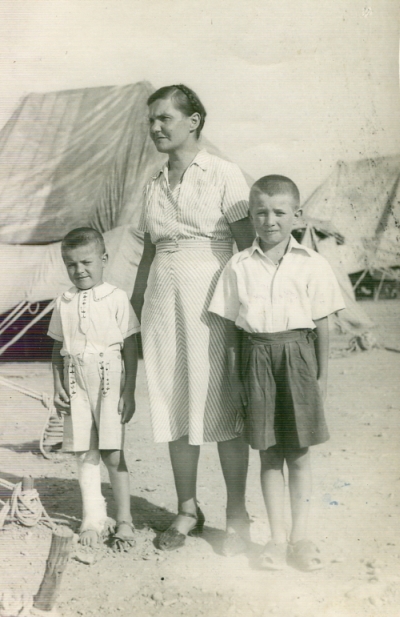

My parents, four grandparents and four uncles were among the 115,000 Poles who escaped the Soviet Union in 1942 through the efforts of the Polish army. Here is my paternal grandmother, Stefania Nieścior, reunited with two of her sons, Rysiek (right) and Janusz, in a Polish civilian camp in Persia, after spending eight months in hospital.

Both my grandfathers enlisted in Kermine, Uzbekistan, within nine days of each other in February 1942. They were posted to different regiments of the 7th Infantry Division. Neither saw his family again.

Władysław was a gunner with the 1 Anti-Tank Artillery Regiment, 1 Armoured Division, 1 Polish Corps. He died in action in northern France on 2 September 1944, aged 36, at a time when Poles still dreamt they could return to a free Poland.

By then, my mother and her younger brother, Janek, had spent two and a half years in orphanages. After Eugenia's death, Karolina Surowiec lost faith in her ability to look after them and gave them to authorities in Uzbekistan. She kept her older son, Staszek, with her.

“And look how happy we all were,” said my mother when we discussed this photograph of her group at the Polish Refugee Camp in Tengeru, then Tanganika in east Africa. She is on the far right.

Stanisław had no illusions of a free Poland when he died on 23 July 1946. Despite Poland's pivotal role in several campaigns (The Battle of Britain, the Falaise Gap in northern France and Monte Cassino between Rome and Naples), the soldiers of the Polish Second Corps still in Italy had no home.

British authorities finally accepted their responsibility for the Poles who refused to return to a post-war communist-controlled Poland.

The Red Cross reunited my mother and Janek with Karolina and Staszek in Rusape, then in Southern Rhodesia.

After five years in Tengeru and Rusape, my grandmothers, my mother and four uncles sailed to Southampton on the carnarvon castle. They landed on 28 June 1948 and were sent to Polish resettlement camps in Devon and Cornwall.

During the trip from Africa my mother and her two brothers begged their mother to let them return “home.” Karolina refused. She would not have known then that Śmigłowo had been razed by Ukrainian bandits during their reign of terror in eastern Poland in 1942 and 1943, but she knew her new home now belonged to Stalin—as did Bratkowice.

Only two of the 50 original houses remain in what was Śmigłowo, which was built in 1938 with 25 houses on either side of one road and water supplied by two wells.39

Practically, what chance did a landless farmer's widow with three teenagers have in Poland? Returning to her family in Bratkowice may have again endangered all their lives.

Stefania Nieścior in 1948 had a more complicated decision to make: She had not seen a child die, but neither had she seen her daughter, Danuta, nor baby Leszek—then 18- and eight-years-old—since the Soviets forced the rest of her immediate family out of their home in 1940. She came from a large, close-knit extended family. Her cousins looked after Rysiek and Janusz while she lay in the Persian hospital, for instance, and they had all stayed together in Tengeru. She could not have always known exactly where in communist-controlled Poland Danuta and Leszek were, but she had to believe they were being looked after.

Babcia Nieścior knew that not only had her marital home in Niweck been absorbed into post-war Soviet Ukraine, but also Zarzeczyca, where her parents and most of her extended family had lived, and even Kazimirka, where she was born. An uncertain situation in Poland weighed against the certainty of her son Zdzisław already in England with the Polish Resettlement Corps, the two sons with her, and the widow's pension she had fought for after her husband died.

Both widows lived out their lives in England, neither ever properly settling or learning the language.

Always quiet babcia Karolina remarried and lived for many years at the Polish Resettlement Camp in Stover. She divided her time between caring for her wounded husband, veteran Piotr Rozwadowski, and her vegetable garden, where she seemed to get solace. They died within three months of each other in 1983.

Stefania Nieścior was far more feisty. From working in the dining room at Stover camp, she moved to the Polish boys’ boarding school run by the Marian Fathers in Hereford, where she worked as a carer and later as a cook. In this photograph, taken by the hereford times40 in February 1965, Stefania is seated second from left.

She transferred to the Polish boys’ boarding school in Fawley Court near Henley and cooked for the pupils and staff until she retired. When she died in Luton 2001, aged 96, her daughter, Danuta Dębicka, made sure she had her wish to be buried on Polish soil. Her grave is in Puck, beside Danuta, who died in 2004.

Zdzisław Nieścior died five months before his mother and Kazimiera Surowiec Nieścior on 14 December, 2016.

© Barbara Scrivens 2015

Updated September 2017

ENDNOTES:

- 1 Anonymous, The Dark Side of the Moon, 1946, page 63, Faber and Faber Limited, London. Author later identified as Zoë Zajdlerowa.

- 2 See recollections from Bronisław Bojanowski (Polish Veterans) and Anna Piotrkowska (Pahiatua Refuge).

- 3 The Junackie Szkoły Mechaniczne (JSM) came under the umbrella of the Junacka Szkoła Kadetów (JSK).

- 4 The word “camps” is not be strictly correct as it gives the impression that the NKVD family facilities were humane. I have used it here because Zajdlerowa explains later the differences between the places families were sent to, and others. Soviet instructions called them “penal institutions.”

- 5 Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace library at Stanford University, California.

The main archives are available through http://www.hoover.org/library-archives. - 6 Zajdlerowa, page 50.

- 7 Ibid, 51 & 52, Zajdlerowa summarised the instructions of order 0054.

Tadeusz Piotrowski, editor of The Polish Deportees of World War II: Recollections of Removal to the Soviet Union and Dispersed Throughout the World, re-printed in full Serov’s Instructions Regarding the Procedure for carrying out the Deportations of anti-Soviet Elements from Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia. Mcfarland & Company, Inc, 204-209. Zajdlerowa pointed out these instructions in Poland were “extended.” - 8 Ibid, Piotrowski, 203–204.

- 9 Zajdlerowa, 59 & 62.

- 10 Ibid, page 47.

- 11 Ibid, page 56.

- 12 Ibid.

- 13 Ibid, page 60.

- 14 This and the quotation above, ibid, page 61.

- 15 Ibid, page 70.

- 16 Ibid, page 65.

- 17 Ibid, page 66.

- 18 Ibid, page 67.

- 19 Ibid, page 69.

- 20 Ibid, page 64.

- 21 Ibid, page 70.

- 22 Taranaki Herald, issue 2991, 3 December 1878, page 2, STAR PANTOMIME COMPANY, Papers Past, through the National Library of New Zealand.

- 23 New Zealand Tablet, Volume III, issue 150, page 14, POLISH PRIESTS IN SIBERIA, Papers Past, through the National Library of New Zealand.

- 24 Zajdlerowa, 21 & 22.

- 25 Anders, Władisław, An Army in Exile: The Story of the Second Polish Corps, originally published 1949, reprinted 2004 by Battery Press, Tennessee, ISBN: 0-89839-043-5, 71-79.

- 26 Zajdlerowa, page 17.

- 27 Ibid, page 19.

- 28 Ibid.

- 29 Ibid, page 20.

- 30 The KARTA Centre, www.karta.org.pl/ carries a comprehensive list of Poles forcibly removed to the USSR in 1939-1956 in its Index of the Repressed, http://www.indeksrepresjonowanych.pl/indeks

- 31 Original copy held at the Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace library at Stanford University, California. If you are looking for a similar document, and cannot find it through their site, http://www.hoover.org/library-archives/collections, write to us through the Contact Us page.

- 32 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Soviet_Census_(1937).

- 33 Davies, Norman, Europe at War 1939-1945: No Simple Victory, 2007, Pan Macmillan (paperback edition), London, ISBN: 978-0-330-35212-3, page 299.

- 34 Ibid, page 276.

- 35 There are several population statistics. I have chosen the ones from the website http://www.populstat.info/Europe/polandc.htm.

- 36 Figures compiled by the Polish Embassy in the USSR from 1941-1943 and now kept at the Hoover Institution (see website above).

- 37 These figures come from the late Jagna Wright, who spent the last 15 years of her life researching the background for the film A Forgotten Odyssey, the Untold Story of 1,700,000 Poles Deported to Siberia in 1940, which she wrote and directed and produced with the late Aneta Naszyńska.

- 38 Ibid.

- 39 This photograph was given to me in by Anna Kidacka, who visited Śmigłowo in June 2010.

- 40 If anyone can confirm the specific occasion the caption to this photograph, please get in touch with me through the home page.