THE POLISH CAMP, PAHIATUA, 1944–1949

by Alexander Henderson, a teacher

How did I become involved? My hometown was Napier, where we had lived since my parents arrived in New Zealand from the UK in 1924. Across the road lived a Catholic family and in 1945, they were hosting a couple of Polish boys from the Polish Children’s Camp in Pahiatua for the holidays.

The mother asked me if I would be prepared to help with the holiday plans by taking the boys along with her kids swimming, to the pictures and so forth. I agreed without hesitation as I was very interested. At the time, I was training to be a teacher.

Well, I was absolutely fascinated. It was my first experience of trying to make myself understood and trying to understand what was being said to me in another language.

The holidays ended and I went back to work, and didn’t think too much more about the camp. However, early in 1947, on reading through the education gazette while teaching in Wairoa, I noticed a teaching position advertised as vacant in the Polish Camp School. I applied, was appointed, and arrived in April of that year.

Boys from “A” Block marching to Mass on a Sunday in 1947, along one of the camp roads.

My arrival I remember vividly. I had left Wairoa on the evening railcar, stayed overnight in Napier and travelled on the next day to Pahiatua. Though I was excited about the whole expedition, I was also somewhat apprehensive, unsure about what I had let myself in for.

I had never been to the Wairarapa before and was a bit concerned about the change of trains at Woodville. As it turned out, there wasn’t much of a wait for the Wairarapa train, but what a clapped-out old junk of a train it was. The couple of carriages which made up the train were vintage 1900, I think—bolt upright hard bench-type seats with feeble gas lighting casting an eerie shadow throughout the carriage. And what a strange cargo of people, and even one or two crates of hens and chickens squawking away at the tops of their voices.

However, my real concern was that I would get off at Pahiatua, so I kept a pretty tight eye on where we were heading. At last, we stopped at Pahiatua. It was very dark and the station seemed to be in the middle of nowhere. As I got off, two young men, one tall, one short, approached me and asked me two questions: 1. Was I the new teacher? 2. Did I play football? To the first question I answered “yes” and to the second “no.”

I felt they were disappointed but without more ado they led me to an army station wagon where a soldier driver told me to put my gear into the back. The two teachers got off in Pahiatua to attend football practice while the driver and I headed on to the camp, about seven kilometres away.

He drove me to the back of the camp where, among larger buildings, there were some two-men army huts. He showed me into one and said, “This is your digs,” and turned to go. I was hungry, as I hadn’t had much all day, and I asked him if I could get a meal or something to eat. “Sorry mate, canteen and cookhouse has shut down for the night,” and with that he left me. I felt completely at sea and not a little crestfallen. To make matters worse, I had no idea of how the camp worked, no idea of what was expected in the morning. And before I’d managed to organise myself, the lights went out. The next day, I discovered that the camp lighting went out every night at 10pm. So there I was trying to make my bed, unpack in the dark and wondering what in the hell I’d gotten into.

Next morning, I did manage to get some breakfast and learned I was attached to the Sergeants’ Mess. As time went by, I found that the army, which officially ran the camp, had some funny rules, which applied to us no less than anyone else.

For instance, the lady teachers and school principal were attached to the Officers’ Mess which we male ordinary teachers weren’t allowed into. The women teachers lived in a compact house called the WAAC’s quarters (Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps). It was a really nice fully self-contained unit with a kitchen, bathroom and three beautiful bedrooms. We men teachers were officially not allowed entry there either, but we would go there for supper anyway. I found the army rules slightly irksome and in many ways stupid. But you did in the end get used to them and found your own ways around them.

After breakfast on that first day, Mr Hugh McKinnon, the principal, got hold of me and told me some things about the camp, most of which were bewildering and most of which I promptly forgot or successfully muddled up.

He took me round the various parts of the camp and I become increasingly amazed at the size of the place. Early on in our tour, we called in at the camp headquarters to meet the Camp Commandant, Major Finney, who was the complete caricature of the traditional British army officer. He unnerved me and I was glad to move on to my next hurdle, which was to meet the Polish delegate, Mr Zaleski. He was a short and tubby man, very welcoming, with a great smile and highly polished manners. That was a relief!

As we went down the streets, I was conscious of being sized up by large numbers of peering eyes and I began to feel uneasy again. I had a tour of the school, received my brief and timetable, was introduced to various Polish and English teachers, and then to my classes—and had the rest of the day off to settle in.

There was a tremendous lot I did not know about teaching children and adults from another culture, which I couldn’t possibly get clued up on in five minutes. I asked Mr Mac as we were walking whether the children were all Roman Catholic, to which he replied, rather cynically I thought, “Well, if they weren’t when they were driven out of Poland, they are now.” I thought, “Henderson, you’ve got a lot to learn here and you’d better learn fast.”

I found settling in quite difficult and appreciated to some extent what being adrift and lonely must have meant to these kids I had come here to help teach English. I didn’t know anyone, not even the New Zealand teachers. To make matters worse, I was pretty green to the ways of the world. In hindsight it was my growing up time.

Sisters Monika Aleksandrowicz, with tie, and Imelda Toboloska, two Ursuline nuns who shared experiences with the Polish refugees in the USSR. They helped care for the children in orphanages in Isfahan and were among the 105 adults who accompanied the 733 children to New Zealand. The nuns were later recalled to Poland.

The first two weeks or so I was at a rather loose end outside school time. The others had their own pursuits and camp life was in many ways a solitary way of life. To complicate matters even more, when payday came there was no pay for me. I was alarmed as I had very little reserves of money. When I made enquiries, the other teachers told me I would be lucky to receive any pay within the next month or so. I thought they were having me on and I was not very happy about it.

At the beginning of September, when I was desperate for money and owed various people in camp about £15, a small fortune to me at that time, I complained to Hugh McKinnon quite bitterly about having not received any pay since arriving at the end of April. He at last got into action and contacted the Prime Minister’s Department in Wellington.

The response was rapid and from the Prime Minister Peter Fraser himself. He telegraphed Mr McKinnon and instructed him to inform me to report to the Bank of New Zealand in Pahiatua that very afternoon to uplift my pay. It was a very happy and relieved teacher who returned to camp that night.

A little sideline to Peter Fraser. In 1945, while still at Wellington Teachers’ Training College, I had the male lead in that year’s drama club production, which was a play currently showing on London’s West End. It was called uncle harry and Mr Fraser, his wife, and his granddaughter Alice (later to become well known on the New Zealand stage and TV screens) came to see our production.

After the show I met them in the college supper area where they talked to me for a few minutes before I went to the dressing rooms to remove my makeup.

I never gave the meeting another thought. However, unexpected things happen occasionally, and while I was in camp, Mr Fraser made a visit there. When he was escorted into my classroom, you can imagine my surprise when he walked up to me saying, “Good afternoon, Mr Henderson. You certainly look a great deal different now from the last time I spoke to you in the supper room after your performance in uncle harry at the Training College.” I was quite floored that a man who meets hundreds of people a week could remember the likes of me! What a marvellous facility for a politician to possess.

When the pay business got critical for me, it was suggested that I approach the local Member of Parliament, Mt K Holyoake, then in the opposition, and get him to somehow do something about it. The opposition were at that time very anxious to have a probe into the running and cost of the camp. I told Mr McKinnon that I did not want to be the instrument to set off any inquiry into anything to do with the camp and I am still today very pleased that despite wanting my money very badly, I resisted the pressure that was put on me.

Until I was a bit more settled, I filled my out-of-school time talking to anyone who would pass the time of day and visited the sick children in the camp hospital. Some of the children had been patients since they arrived in New Zealand. Sister Johnson, the hospital matron, was an interesting and kindly soul whom I enjoyed talking to.

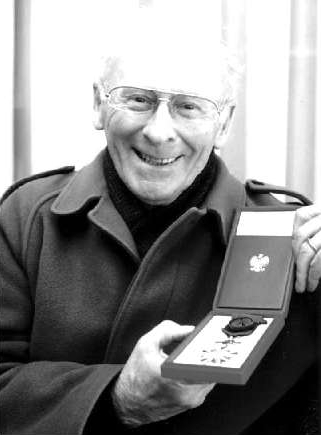

Alexander Henderson, soon after he arrived to teach English at the camp. With him is Ann Jacques, organising secretary of the Polish Army League. The PAL, made up of women from nearby Palmerston North, had been one of the forces behind the setting up of the refugee camp in Pahiatua. They had established the league two years earlier, specifically to help alleviate the loneliness of Polish soldiers in the Middle East, and had motivated thousands of New Zealanders to write to the soldiers, and donate goods for “comfort” parcels.

Bit by bit, I began to find my feet and formed friendships with some of the teachers, especially Joan Hay, who took me under her wing and guided me through the ways of camp life. Things were definitely on the up and up. I was also beginning to have more contact with some of the Polish adults.

This was particularly pleasing, for I really did want to learn as much as possible about these people whose culture and life stories fascinated me. What could they tell me of their history, their homeland, their own personal stories, their deportation to Russia, their trek through Soviet Central Asia and into Persia [Iran]? It may have seemed a tall order, but over the years in camp I was able to build up a fairly comprehensive understanding of what being Polish was all about.

But to get back to the beginnings. I found some of my classes difficult to handle at times and I was sure some of the things they were saying to me were not complimentary. I wasn’t used to this sort of thing and I didn't know how to handle it. Marian Olechnowicz, one of the Polish teachers, was very kind to me so I approached him with the problem. I asked him what the boys were saying when they scowled and said such things as “cholera ty!” (a curse meaning may you get cholera), “durna koza” (stupid goat) and “głupi ty” (You are stupid. / Are you stupid?). Not that I said these words terribly clearly, but he understood.

He gave me some strategies to try on them and agreed to tutor me in the essential Polish swearing vocabulary. With Mr Olech’s help, I soon had an efficient command of Polish curses and swearing. When the troublesome boys realised that I was aware of what they were saying to me, things improved markedly and we settled down to a much more harmonious time

When a new male teacher came to camp, the boys took great delight in greeting the said arrival with a grinning “Good morning, Sir.” It sounded a little strange, though, and you sensed there was a joke somewhere, but what? Then from one of the teachers you would find out that the Polish word for cheese is “ser,” so in the boys’ minds they were saying “Good morning, Cheese.”

Talking of unfortunate words—not more than three or so weeks after arriving in the camp I was invited to an afternoon tea party that was hosted by Drs. Czochańska and Dawidowska. I duly arrived and was welcomed in a most charming way by everyone present.

We began by having tea with lemon or milk, or whatever way you wanted it. Accompanying the tea was a most wonderful spread of scrumptious examples of the Polish kitchen. The cakes were just marvellous, and I was so taken with one lemon cake that I said quite loudly, “Oh! This cake is super-duper.”

Well, the hush that descended (once the cups stopped rattling on their saucers) was almost deafening.

“Oh! Mr Henderson, you cannot say that!”

“What?” I asked and reddened. “What have I said?”

“No! No! You not say that!”

The way it was said warned me the conversation on that topic was closed. I didn’t enjoy the rest of the afternoon. Later in the day, I went to Mrs Tietze’s house—the head teacher of the Polish primary school. As she had also been at the party, I asked her what on earth I had said to have caused such a stir. She was very reluctant to tell me but I pleaded with her to tell me as I didn’t want a repeat performance.

She got out her dictionary and with a very red face said, “It is a very bad name for here,” pointing to her seat. Then I really went red. As I thought about it, I suddenly roared with laughter, for in effect I had said, “This cake is super arseholes.” I never used the expression again. It now seems trivial, but in 1947 it certainly wasn’t afternoon tea talk.

Soon after my arrival in camp, we celebrated the Third of May Constitution of 1791, Poland’s National Day. This was my first real introduction to the Polish way of life. In the early evening in the camp hall, there was an official commemoration concert at which we were treated to an evening of Polish orations, songs and dances. I hadn’t a clue as to what was happening but something clicked within me. I was on the road to wanting to know much more about Poland, its history and its culture—to learn as much as I possibly could.

Come Monday, I headed for the Polish/English library where there was a reasonably good selection of books, mainly sourced from the printing presses in and around Chicago, which had a Polish population of several million people. Luckily for me, there were a number of excellent translations.

After about four months, I was completely at home in the camp, enjoying teaching and just being part of camp life in general. The anxieties of the first weeks were well and truly behind me—even the fear of earthquakes. This fact would probably seem funny to most people, but I had been through the 1931 Napier earthquake and in my first week in the camp there was an earthquake swarm which I found totally unnerving. I remember thinking that if this was how things were going to go on then I didn’t think I’d be able to stick it.

Weekends were always interesting. Saturday mornings were usually given to cleaning out the hut, doing the washing and those sort of chore things I hated having to do. At least we didn’t have to do our sheets and towels for these were changed each Thursday by the army, which I think had a contract with a laundry in Pahiatua.

Afternoons were much more interesting. In the winter, I used to wander the hills, riverbanks, usually with some other teachers and very often with some of the other Polish people, especially Pani Jadwiga Tietze, who was almost like a second mother to me. She was my mentor in things Polish, in affairs of the heart, listening to my troubles whatever they were, offering ways of dealing with things.

Maybe to the camp adults and kids we didn’t appear to have anything to concern us but we were just ordinary people and we did worry, we could go wild, we could get grumpy—in many ways we weren’t any different. I really enjoyed those tramps around the countryside and I learned a tremendous amount about the New Zealand landscape that prior to Pahiatua, I knew nothing of.

Of a Saturday evening if there was anything special on in the camp we would go off to that, a national day concert, an outside concert party visiting camp. In fact, anything out of the ordinary. If that was the case, we would usually have supper somewhere in the camp and occasionally set up a bit of a party in the WAAC’s sitting room. It was usually noisy, harmless and a lot of good fun.

On other Saturdays we headed off to wherever there was a dance, such as Pahiatua, Mangatainoka, Hamua. We usually had a pretty good time at these dances, flirting with the local girls, sometimes upsetting the local young men—but that didn’t bother us and we survived without any fist fights or suchlike. I guess we were just letting off steam.

Frank Muller and Andy Nola were in the Pahiatua football team. Through their association we came to know a few local married and single people who invited us for the occasional meal or party. They always included all the New Zealand teaching staff. It was a pleasant change sometimes to enter an ordinary house setting from time to time. I didn’t wonder then but I did later, how the Polish adults and kids must have felt cooped up in dormitories or pokey little bedsitters in the camp.

Sundays were given over in the mornings to Mass, usually at 9am in the camp theatre. At first, I didn’t get up very early on Sunday, but one Sunday not too long after I arrived, I decided I would like to go to the Polish Mass as I was curious to see what it was all about. I asked the other teachers whom I knew would be going if I could go with them. They said that would be fine—no questions, not even a funny look.

When we came into the theatre it had been transformed from a theatre to a church by the simple opening of a cupboard altar arrangement, which I had previously not noticed. Everything was in Latin, and what wasn’t, was in Polish. I didn’t understand a thing that was going on but in some indefinable way I was much moved. Their singing had a wonderfully refreshing quality about it. It haunted you. It made you want to hear more—and I did over the ensuing years.

Inside the camp chapel, which was too small to hold the numbers that attended Mass on Sundays, held in the main hall, its stage transformed into an altar.

Gradually with time and a Mass book with the English translations, I began to get the gist of things. I felt happier and more secure in this part of my life than I had ever felt before.

Then came a devotion called Benediction. My first experience of it completely bowled me—such wonder, colour and sense of the Holy as I had never before felt. It was almost too much. I was completely overawed. To this day, Benediction has always remained a greatly loved devotional service within me.

Matka Boska Częstochowska, a revered icon in the monastery of Jasna Góra in Częstochowa, was given especial devotion in the camp and as I found out more of the story, I found myself drawn to this favourite, also known as the Queen of Poland. I acquired a small black and while card bearing the image, and it went with me everywhere. Now it is rather battered in looks but loved all the same for it embodies a history.

I was intrigued as to why the image had a slash across the face, and this led to the discovery concerning the Swedish invasions of Poland. During one of the invasions the Swedes got hold of the icon and a soldier apparently slashed the image with a sword. [Other stories say it was a Tartar invasion and a Tartar arrow.] This is an icon of great power, and I have found much support through devotion to Our Lady of Częstochowa. I became a full member of the Catholic Church, a decision I never regretted.

No dissertation of weekend life in the camp would omit to mention the Sunday night dance in the gym where Miss Merwid of the camp and Mrs Watson from Pahiatua played a great old mixture of Polish and English-American tunes.

One thing that made the dancing interesting was that Miss Merwid had a liking for sherry and as the night progressed her playing was apt to increase in speed and consequently we were all swirling around like dervishes. Absolutely great fun nevertheless!

Late in 1947, it became clear that the political position in Poland had changed. The New Zealand Government decided that, as many of the children would now probably remain in New Zealand, the main teaching in the camp school should be conducted in English. In some ways, this made things easier for us from an administrative point of view, but to this day I have no idea what input the Polish staff had in the decision.

It was the one thing that rather saddened me in the teaching area. Our contact with the Polish teaching staff was minimal and we had little knowledge of their work programmes, and I am sure they had little of ours.

As teachers, we were given no courses or real guidelines on how to teach English as a second language, hence our approach was mostly trial and error. This meant much heartache in the beginning, and you didn’t get anywhere until you gave up your preconceived ideas and adjusted to new ways of control, teaching and general approach.

All that being so, you could still fall foul of the system without even trying, as for instance when Father Plater bailed me up after having taken my class for religious education. As I was about to return to my room, he asked me why was I teaching about Adam and Eve in a way contrary to the church’s teaching. At first I had no idea what he was talking about, but after questioning him a bit further on the matter I realised he was referring to some work we were doing on the cavemen. I explained to him what we were doing and he rather dubiously, I thought, caught on by saying, “Ah, so. Well, the boys have mixed it up as Adam and Eve, and anyway they probably think Adam and Eve were Polish.”

“Father,” I replied, “I am here to teach English, not to take religion classes. I am sorry about any mix-up there may have been.”

And in my head I thought, “God help me. There are traps everywhere you step in this camp.”

Fr L Plater, the second Polish chaplain, who arrived from London early in 1948.

Fr Michał Wilniewczyc, the first Polish chaplain at the camp, survived forced-labour in, Siberia and accompanied the children from Iran to New Zealand. The Vatican tranferred the much-loved priest to Lebanon in 1947.

Pahiatua is situated on a flattish area in the northern Wairarapa with the Tararua Ranges a few miles to the west and the coastal hills to the east, which made for a fairly hot summer and rather cold wet blustery winter. The whole area was a great place for kids to explore and have a close look at the world of nature around them, and a great teaching medium too.

It’s the only place I know where in one night it can freeze, rain, and freeze again by morning. It was often intensely cold, foggy and icy around school starting time.

The school was at the outer fringes of the steam-heating system and the heat took ages to get through to the classrooms. It was not an unusual sight to see hundreds of Polish kids in their khaki outfits, boys with shorn heads and girls with their hair plaited, jogging along the main road with large puffs of exhaled air from each of them forming a veritable cloud of steam. And we teachers were puffing our way around the block also. It was a great way to get warm, believe me.

Another event worthy of recording was The Mushroom Trail, which took place whenever the weather was right for mushroom growth. I’d set off with the class with a sack or two, and head into the hills to gather these wonderful delicacies. The boys particularly enjoyed romping over the hills and enjoyed the mushroom gathering as much as I did. It was also a great time for conversation about the world around us, and somehow the open air seemed to loosen up tongues and shyness about using English disappeared. So there were two-fold benefits—food and English language practice. Every camp kitchen during the mushroom season serving mushrooms cooked in a variety of ways. In fact, prior to being in the camp, I had always thought there was only one way to cook mushrooms. However, the haul of mushrooms wasn’t cooked at once. As you went from house to house, kitchen to kitchen, you would find lines of them strung up across the ceiling drying out to be stored for use in later cooking as flavourings.

One was immediately aware of the many notices stretching for some distance in the environs of the camp, warning that some areas were “No-go” zones, such as “Uwaga! Uwaga!” (Beware! Beware!) This had been brought about by the children going on a spree after settling in—and such things as raided vegetable gardens and fruit trees, and the total dismantling of a farmer’s tractor hadn’t been terribly well received by the locals.

There was another side to the coin, however. One had to realise that these children had learned to be survivors; they’d led a tough unrelenting life since their deportation from Poland to the outer reaches of Siberia, some way beyond the Ural Mountains. Such sorrow! We had to learn that fact and understand that they had to learn the rules of yet another new country.

Their vigour and lust for life showed up in the area of sports. They took to rugby football, basketball (now netball), cricket and softball like ducks to water. Very soon, under the excellent guidance of two other teachers Andy Nola and Frank Muller with me as a sort of learner, the boys became “The Fear of the Northern Wairarapa” where Polish teams usually swept the field in rugby and gained many victories. The girls, so ably tutored by Mary Eising, Joan Hay and later assisted by Pat Sloan, were no less successful with their netball teams.

Talking about sports teams also reminds me of another debacle I got myself unwittingly into at the start of my term of duty in the camp. The occasion was during the King’s Birthday weekend of 1947. The older boys were travelling to Masterton accompanied by Frank and Andy to an inter-school senior primary school rugby tournament. They asked me to accompany the junior boys to a similar one in Pahiatua. The arrangement was that we would have army transport to the grounds but would have to walk the seven or so kilometres back to camp at the end of the day. That seemed quite reasonable.

However, no one had planned on a violent change in the weather. About 2pm, the sky just opened up and within minutes everything was awash. The thought of getting all those kids back to camp safely in such weather was to say the least, very off-putting—perhaps if I rang the camp they might just take pity on us and arrange for some transport?

So I duly rang the camp, and got Pani Zaleska and told her my predicament. She asked me to hold the line while she made some inquiries, and she came back with the news that a transport would pick us up at 3pm. I was delighted that the problem had so easily been resolved. We arrived back in camp in one piece and considerably drier than we would have been.

I never thought another thing about the incident until a few days later when I was walking down a camp street towards the school and the adjutant, Captain Forsythe, suddenly appeared from out of nowhere and bellowed: “Henderson! Come here!” The tone was distinctly icy, so I knew it spelled trouble.

“Yes, Captain. What do you want?” I asked as pleasantly as I could.

“Who said you could order army transport as and when you want it?“

“I rang the camp to ask if it would be possible to have transport because of the downturn in the weath…”

He cut in very sharply and told me in no uncertain terms where I stood in this hierarchy, finishing his tirade by saying rather loudly: “And in future, keep your bloody nose out of transport, because if you don’t…” He didn’t finish the sentence. There was no need to. The meaning was clear. “Captain,” I said, “I never had any intention of ordering anyone to do anything but you can be quite sure I’ll make sure to keep out of your field.”

With that, I left him standing there and headed to the school feeling annoyed. I never really discovered how the ballsup occurred but I suppose it was crass ignorance on my part—just another part of the learning we all had to do while in camp. Relations between the captain and me were never particularly cordial from that time onwards. We tolerated each other because we had to, I suppose.

The summer days saw all of us down at the waterholes in the river about half a mile across the paddocks from the camp. Of a weekend, the area was a hubbub of noise and shrieks of laughter as kids dived, jumped from the banks, heaved rocks and generally let-off steam.

On 20 July 1995, Polish President Lech Wałęsa honoured Alexander Henderson with the Officers’ Cross of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Poland, the highest Polish award that can be bestowed by Poland on a citizen of another country. The award acknowledged the former teacher’s effort to learn the language of his pupils at the camp.

Looking back, I’m amazed that I don’t remember anyone being hurt in any way despite the mayhem. In today’s world, we wouldn’t have been allowed such freedom. Life is now too much controlled and I sometimes feel we have become too safety minded, and have in some ways stolen adventure from our children.

I am forever grateful that my curiosity led me to make inroads into the Polish community and to gradually learn a great deal about a culture that was light years away from my own. I lapped up people’s stories of their lives before the war and in captivity, and their family ties, schooling, religion, countryside and history. I found myself being absorbed into their life patterns, so that when I left the camp when it closed, it caused me quite a few problems and I couldn’t always speak English exactly correctly.

There has remained in me a great love of these people. I had learned to laugh, cry and in many intangible ways to share their lives. It has never left me and forever a part of me will always relate to Poland. My memories of the hard times and the celebrating times will move me to tears along with them.

If at a Polish Mass, which from time to time I have over the years attended, they begin to sing Boźe, Coś Polskę, I can’t help joining in with my distinctly eastern Polish peasant accent. And how do I know I’ve got such an accent? Once, when Mrs Zaleska heard me speaking in Polish, she laughed and said: “Oh, Sandy, you will never pass in Warsaw with that eastern Polish peasant accent. We really should take you in hand and do something about that accent.”

Well, we didn’t, and I’ve always been quite happy just to be understood.

© Alexander Henderson, 1994.

_______________

OTHER STORIES ABOUT THE PAHIATUA CAMP AND THEIR POLISH INMATES ARE AVAILABLE THROUGH THE MENU ON THIS PAGE, AS IS THE STORY ON ANN JACQUES AND THE OTHER FORMIDABLE WOMEN OF THE POLISH ARMY LEAGUE.