Tadeusz Zioło,

Danuta Zioło Gawronek &

Alina Zioło Toth

Interviewing the Zioło siblings together last October was a joy and a challenge. Much as I tried to follow three threads of the same story, I knew I would have to return to clarify details.

There is no doubt about their love for one another, their shared closeness and their camaraderie. Tadeusz, the oldest, teases his sisters—a brother’s job—and takes their teasing in return. Danuta and Alina sound similar, and finish each other’s sentences.

Second interviews with Pan Tadeusz alone, at his home in Rangiora, and the sisters together in St Albans, Christchurch, filled the gaps about how these three Poles got to New Zealand in 1944.

In February 1940, armed Soviet soldiers removed the entire family from their farm in eastern Poland, and detained them in an NKVD forced-labour facility in Siberia. Their parents guided them out of then-USSR, but died soon after reaching freedom in then-Persia. Tadeusz, Danuta and Alina Zioło were among 733 Polish children and 105 adults who received refuge in New Zealand.

They each lost their childhoods in 1940. Pan Tadeusz, then nine, spoke about how he had to be an adult after his father died, because that was what his father asked of him. Pani Alina, then three, says she was the “luckiest” in that she was too young to remember much before she was in Persia. Pani Danuta developed an elegant shell.

I thank them for sharing their often-painful memories and for their kindness, generosity and patience, all of which I appreciate.

—Barbara Scrivens

SURVIVING ‘PARADISE’

by Barbara Scrivens

Jan Zioło’s father pointed him towards the land of opportunity and Jan understood why: the family farm in Sulisławice, about half-way between Lublin and Kraków, would soon be too small to support his parents, his seven brothers, and his sister.

Jan, the eldest, had added to the brimming household by marrying Marianna Harian and having three children of his own, Tadeusz, born in 1931, Danuta, born in 1934 and Alina, born in 1937.

Meanwhile, eastern Poland offered possibilities, freedom and the cheapest land in the country. Jan Zioło found several hectares in Czarnowice, close to Tarnopol, and moved his family there in 1938.

Tadeusz: “Dad got much more land than he would have with grandfather. Czarnowice was a new village then; there weren’t many of us, all beginners, starting a new life.”

Tadeusz missed his grandparents, whom he knew only as babcia and dziadek. They lived next door, in the main part of the Sulisławice farmhouse, and he visited their kitchen daily.

Danuta has three memories of the new farm: a meandering stream, the children throwing balls with their mother, and walking into the kitchen one day.

“It was spotless and two ladies were there. One was my mother and the other must have been my aunty. I think they were making pierogi.”

Tadeusz: “It must have been Christmastime. In Poland, for wigilia [Christmas Eve meal], you put hay on the table, cover it with the tablecloth, then put a wafer—opłatek—in the middle and wish each other… I miss those things. They were good.

“Dad was happy in Czarnowice, and in two years he made the land pliable. He ploughed, put in manure, put in an orchard near the house…”

Danuta: “… and vegetables.”

Tadeusz: “… and the rest farther out, like wheat…”

Danuta: “… and corn, and cabbages, and onions…”

Tadeusz: “He was hoping that he would get something from the orchard because he planted quite a few trees—apples, plums and pears. I helped him with those trees.”

_______________

“… that night, they were supposed to come and attack us and kill us off, if we were still on the farm.

The Russian invasion of Poland on 17 September 1939 emboldened the Ukrainians who lived in eastern Poland: many took the opportunity to claim for themselves the land that the Poles had improved.

“They told some of the people in our village that we were not supposed to be there. The Ukrainians wanted the land, and said that if we didn’t shift by a certain time, they would kill us.”

Danuta: “And they would. They were cruel, worse than the Russians.”

Tadeusz: “The men from the village knew that if they were going to individually protect their families, they stood no chance, but as a group they would be able to fight the Ukrainians. Dad told us—or told mum and I listened—that night, they were supposed to come and attack us and kill us off, if we were still on the farm.

“There was only one road coming to Czarnowice and the men knew they could protect the village from there.

“There were two brothers living on opposite sides of the next village. They had two tractors, but one was broken. One brother said to the other brother that he needed to borrow a part from his good tractor. They agreed that they would shift that part, the steering wheel and column, by horse, through the village.

“Outside of the tractor, the part looked like a machine gun. It was so big and awkward, they tied it to the brother riding the horse. But, as he rode through the village, the noise of the people scared the horse, and the horse took off. The fellow who sat on the horse, got to wherever he was supposed to go, but the Ukrainians heard all the commotion—and maybe saw him too—and said, ‘That’s the Polish army, waiting for us to attack them.’ They were more scared than we were!

“The night they were supposed to kill us off, Dad left with the other men. At home, mum and I were saying the rosary. Danuta was sick with a cold or ’flu; Alina probably slept. Every so often, mum went to see whether Danuta was all right. She told me to keep praying.

“The men stayed together until the morning. Then they went home. The Ukrainians didn’t come, so we stayed. A week later, we were deported.1 The Russians came, loaded us on the train and we were shifted to Siberia.”

“Whenever she could, our mother got off the train to beg for food… and once it went without her.

Three or four armed Soviet soldiers arrived at the Zioło home early one snowy February morning in 1940, forced Jan Zioło to stand in a corner, and told Marianna to dress her children, ready for a trip to “Paradise.” The soldiers told her to pack only what they immediately needed. Sledges took the family to a railway station where Soviet soldiers loaded Poles into rail wagons that used to carry cattle. Tadeusz saw other neighbours at the station, such as the Błażkóws, who lived in nearby Berezki, and the Zalewski family, whose two surviving sons also settled in New Zealand.2

The train trip into Siberia, east of the Ural mountains, took at least two weeks. Aged nine in January 1940, Tadeusz observed.

“If you wanted to go to the toilet, sometimes the train stopped, and you could relieve yourself. If you were in a hurry, there was a hole in the floor, in the train.

“Whenever she could, our mother got off the train to beg for food. She took a risk, because we never knew how long the train would stop for, and once it went without her. They put her on the next train and, because we stayed at the next station a bit longer, Mum caught up with us. Relief! We got mum back again.”

Tadeusz does not recall the name of their destination, an NKVD (Soviet Secret Police) forced-labour facility detaining “quite a few” Poles, but he knows it was deep in the taiga near a river. The Ziołos shared a house with others, including an “educated woman” with a son in high school.

Among other jobs, Jan Zioło cut hay “quite a distance away” and spent sometimes weeks at an even more remote location. The NKVD commandant sent Marianna and other women to a forest outside the facility to gather smaller pieces of wood that fell during the chopping process.

Marianna had kept her pregnancy from her children, so the appearance of a baby to look after came as a “big surprise.”

Danuta: “Mum used to go to the restaurant, where the [NKVD] officers had their meals, and she used to be on her knees begging for a piece of bread for her children. They used to chuck the bread on the floor, as if to a dog.

“Father was away. I don’t know if he knew what she did. He used to say, ‘I would rather die than ask Russians for anything.’ My mother used to go and beg, but not my father. He hated Russians.”

Tadeusz: “The winter in Siberia was nine months a year. Spring, summer, and autumn happened in the other three months.”

Other boys Tadeusz’s age went to the facility’s Russian school, but he had to look after Danuta and Alina, six and three in 1940.

There were a few occasions when Tadeusz did leave his sisters alone. Once the spring thaw started, he could not resist the cut logs floating downstream.

“If you were fast enough, you could cross the river, jumping from one log to the other—just to see if you could do it.”

The reason why Tadeusz remembers so clearly the woman sharing their house is because she helped Marianna deliver a third daughter, Hania, a few months after they arrived.

Marianna had kept her pregnancy from her children, so the appearance of a baby to look after came as a “big surprise” for Tadeusz.

“We had to carry the wee one to Mum to feed her. Mum was working a distance outside the village, and it took quite a bit of time to walk to her with the three sisters: two walking behind me, and carrying other one.

“When she was hungry, we knew she was hungry because, oh God, for such a small thing, she had a voice. She could cry, that girl!

“When I picked her up and put her in the blanket, or whatever, and carried her to Mum, she stopped crying, as if she knew what was happening. And when she saw Mum, she didn’t want me then. Mum fed her.”

Danuta: “Mum had no breastmilk, no food. They used to give her a little bit of soup for lunch, a crust of bread or something, and she used to bring it to us so that we could have something to eat.”

Tadeusz: “The baby was satisfied that she was sucking. And when Mum finished, she gave her back to me, we went home, and she slept most of the afternoon—until Mum got home and took over.”

Hania Zioło died before her first birthday. The family buried her in the well-used cemetery adjacent to the facility.

“It was just us there. I think dad made something to put her in. We dug the grave.”

Danuta: “She was buried under the snow.”

_______________

Along with hundreds of thousands of Polish civilians incarcerated in the NKVD forced-labour facilities that pockmarked Stalin’s USSR in 1940 and 1941, the Zioło family received an ‘amnesty’3 from the Soviet leader in July 1941. Ironically, they had Hitler to thank for their release.

On 22 June 1941, Hitler launched Operation Barbarossa, and sent his troops to re-invade first Russian-occupied Poland, then invade Russia proper. The Germans raced towards Moscow, and by mid-July 1941 stood barely 300 kilometres away. Stalin looked towards his Polish prisoners, with whom he suddenly shared an enemy.

On 30 July 1941, in London, Polish Prime Minister Władysław Sikorski and Soviet Ambassador to the United Kingdom Ivan Maisky signed a Polish-Soviet Agreement. The Poles in the NKVD forced-labour facilities, gulags and prisons could leave the USSR—in order to form a Polish army that would fight the Germans in western Russia. (See military timeline, 1941.)

News of the Sikorski-Maisky agreement and the ‘amnesty’ took a while to filter to the NKVD forced-labour facilities deeper in Siberia. NKVD commandants, reluctant to part with their Polish labour, did not always help to spread the word. The Poles may have arrived in trains and sledges but that same transport did not materialise to return them. During Operation Barbarossa, which ended in December 1941, the Russian army needed those trains to carry troops to and within western USSR. Even if the Ziołos had managed to find a railway station, they could have waited weeks for a train.

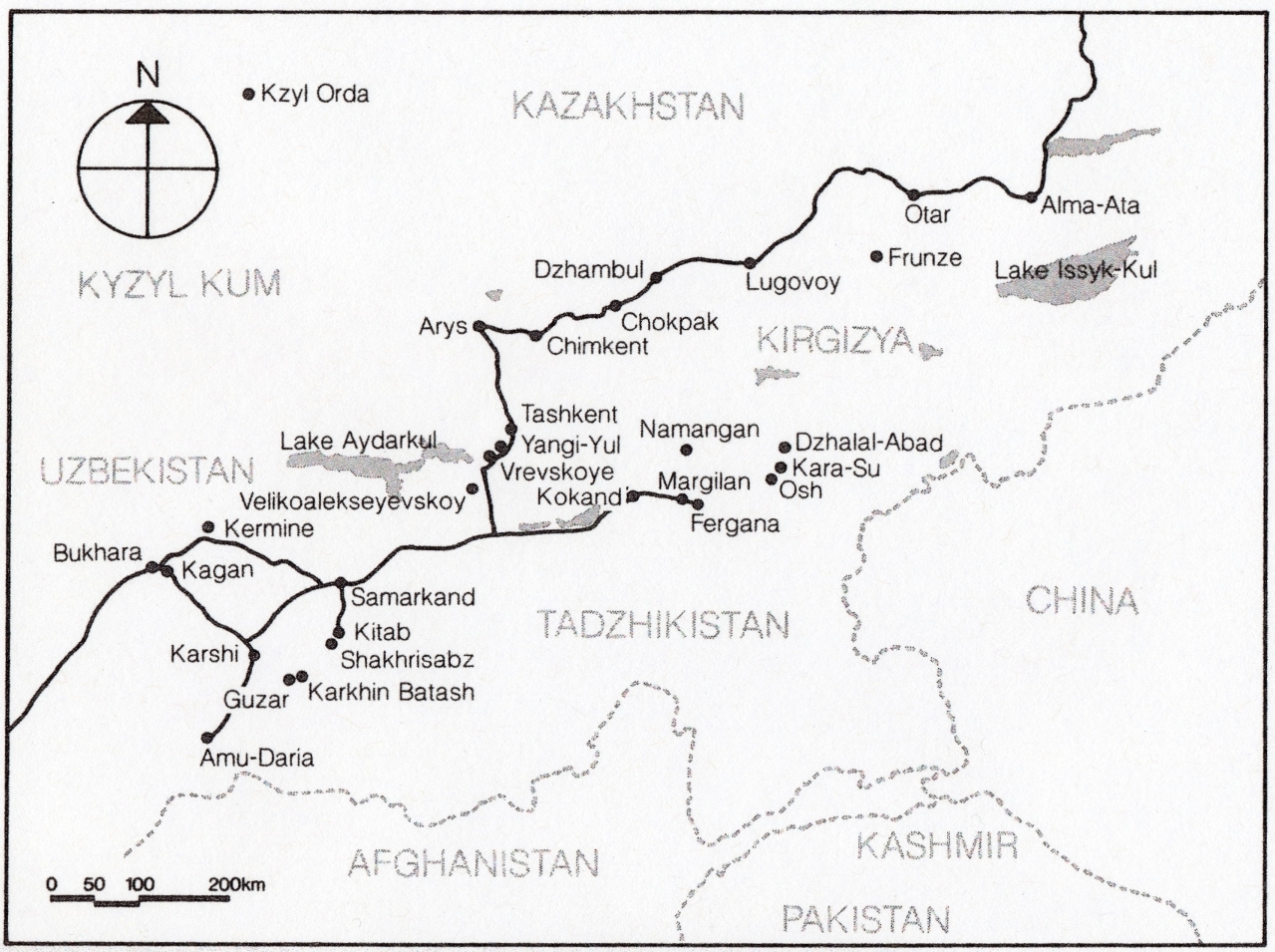

A map showing the Polish military bases established in Soviet South Asia after the Sikorski-Maisky agreement in 1941. The Ziołos passed through this area from the north-east of Kazakhstan.4

“We heard we could get away from Russia, and we did. We had no telephone but the grapevine was very quick. We knew we had to make our own way. We did a lot of walking.”

Tracks between villages showed the way, and they avoided wolves and bears at night by choosing rest spots near human settlements.

“We stopped at two or three places for longer periods, sometimes weeks, because Dad wanted to do some work and get some money.”

It is not clear why Jan Zioło did not enlist with the Polish army, but he took Tadeusz to a camp for junaki, the military cadet school run by the Polish army for teenagers.

“I had typhoid. My parents reckoned that they said goodbye to me when Dad took me to the hospital: they did not expect me to live.

“When I came out, Dad said, ‘The only way to get you right is to put you in the cadets. I don’t wasn’t to lose you, but you will get well-fed there and we can’t survive on what we get.’

“I was in the camp for a while. There were quite a few of us, hundreds, in big dormitories.

“Russian soldiers going to the front… told us we were not supposed to be there, dragged us to the opening between the wagons and just pushed us out.”

“The word was that the junaki were being sent to the Middle East to grow up and join the soldiers later. I went with Władek Błażków5 to join, but I was under age. My father or mother had to sign for me to go to because it was so far away from our parents. I had to wait for a visit from Dad—he came every so often at the weekend—but by the time Dad came, they had already shipped out. There were quite a few of us left behind.”

Jan led his family through Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan towards Krasnovodsk on the Caspian Sea, from where their army had arranged cargo ships to carry Polish soldiers and civilians across to then-Persia.

Leaving an NKVD forced-labour facility meant leaving any ration. Generally, those old enough to work had received 500 grammes of “brown bread, if you could call it bread,” a day and those who did not, 200 grammes. At one of the towns, however, authorities had arranged bread rationing for the starving Poles who travelled through. Despite that bread, Jan and Marianna knew they could not stop moving. They left 10-year-old Tadeusz with the family ration book while they looked for work ahead, cotton-picking.6

“I stayed behind and I learnt: I had the book to go each week to get the bread, and the Jewish people—there were about three or four houses of Jewish people—bought the bread from me. So I was getting bread for five people, but I was on my own.

“There was another man doing the same thing, collecting for his whole family. He was with us in Siberia. His children were older, so the mother went ahead with them, and the father stayed behind, like me, to pick up the bread.

“I don’t know how many months I collected the bread, but one day, an elderly Jewish fellow came to me and said, ‘Mr Zioło, you’d better pack your things and go, because the Russians are after you.’ Somebody reported that I bought with the ration book for five, but I was only one.

“When the Jewish man said we should leave, we caught the train hoping that we could get away quicker, but it was the army train—Russian soldiers going to the front—and they threw us out. They told us we were not supposed to be there, dragged us to the opening between the wagons and just pushed us out. Lucky that the train wasn’t going fast, and we didn’t go under the wheels. We got up from the side of the tracks and started walking.

“We got to a market where they were selling sour cream and milk. I had quite a few roubles in a front pocket on my shirt. It had a lip that buttoned, that I used to do up.

“Before you buy, you taste, and I was going to take it, but I saw that the next one—about a metre away—looked better, better cream, so I didn’t do up my button and I went there. And when I tasted that one, I was so excited with the good stuff, I reached to get the money from the pocket and the pocket wasn’t closed. I had no money.

In the morning there was nothing, no bag, not even my trousers or my shirt.… I don’t know why or how I slept all night like that. I couldn’t even take the bread to the parents.

“Somebody must have been watching me. In the market—everybody cramping together—somebody had lifted the money. I couldn’t get the milk, and I started crying.

“The older fellow with me said, ‘Don’t, don’t do that, don’t make a scene, because if you do, the police will take both of us and put us in jail and you will never see your parents again.’ I think he was worried about his own skin, but I knew it was true, because we were breaking the law, getting bread for five when we were on our own.

“Again we were walking, walking and walking. I still had some of the bread in a bag. We used to dry the bread, so it kept for longer. We were heading towards the village where Dad said they were going to, and the older fellow’s family were going to the same place. We almost got there, but it was too dark for us to carry on, so we stopped at the riverside and went to sleep.

“It was so hot, I took my shirt off and my trousers off, and rolled them up, and put them under my head, my bag too, and slept. In the morning there was nothing, no bag, not even my trousers or my shirt. I was on the grass. I don’t know why or how I slept all night like that. I couldn’t even take the bread to the parents.

“I had only my undies. The older fellow gave me his shirt. I put it on because I couldn’t see Mum like that. The next day, she must have seen me coming along the road—there was only one road—and came to meet me.

“Mum said, ‘Tadzio, don’t worry about the money, it’s thanks to God that you are with us.’”

While Jan and Marianna picked the cotton, Danuta and Alina “did nothing” as they waited next to the fields.

Danuta: “I looked after Alina.”

Alina: “There was some kind of hut. When Ted got back and he saw that we were so hungry, he went to the other man’s bag, took out some bread and gave it to us. We were overjoyed.”

_______________

Tadeusz: “We got to the Caspian Sea, where we had to wait in the queue and report to the authorities, tell them your name and check whether you are on the list, or not, to get on the ship to Persia. Then you had to wait.

“Being Z that usually comes in last, Dad thought that we were too late, but he came back and said, ‘We were lucky, Mum.’ And when they called ‘Zioło, five,’ he said, ‘I am so glad that we made it,’ because hundreds of people were left behind. They couldn’t take everybody, and we were on the last boat.”7

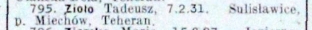

Entries for Tadeusz, Alina and Danuta in the Red Cross list of Polish evacuees from the USSR in 1942.

“We landed in Pahlevi, Persia. They put us in tents because there were quite a few of us on the boat. Dad was already very sick when we landed.”

Danuta: “I remember him…”

Alina: “… on a stretcher.”

Danuta: “He couldn’t walk…”

Alina: “… no energy.”

Tadeusz: “Mum wasn’t well, but she could still look after us. Three or four days later, a doctor come in and said everybody except me had to go to hospital.

“Orderlies from the hospital came to get Dad. He was struggling to walk. He was skin and bone: he couldn’t even stand up. They held him under his arms, and he came over to me, put his arms around me, and said, ‘Tadziu, you’re the only man in the family now. Look after my girls.’ And they took him. He must have known that he was dying. It was the only time he called me Tadziu. Mum used to call me Tadzio and Dad used to call me Tadeusz.”

Jan’s and Marianna’s names seem to be missing from the 1942 Red Cross List of Evacuees from the USSR. Jan’s illness when he landed in Pahlevi, points to the possibility that he and his wife were aware that officials might have stopped them from boarding the evacuee ship for health reasons. That both Jan and Marianna arrived in Pahlevi suggests that they either smuggled themselves onto the ship, or were helped to bypass the list-takers.8

Danuta: “We slept on the sand. They were washing my father, or something, and he looked at me and smiled, and that’s when I saw he had two teeth missing. He smiled at me, and that’s the last time I saw him.”

Tadeusz: “I ended up in the tent all alone, with all the possessions that we had; we didn’t have much.

“You had to ask for permission to leave the establishment and a week later, I asked to go to the hospital. They said, ‘Yes, you can go,’ and I went, and said I had come to see Jan Zioło.

“The nurse was very nice. She said, ‘Son, you will find Dad in the cemetery. They buried him yesterday. He died on 5 May, 1942. The nurse told me where to go, and I found him, and said the Our Father and Hail Mary and Rest in Peace for him.

“He was a tall man walking in front of a little girl in a nightie and no shoes.”

“From the cemetery, I went back to hospital and asked about Mum. They said, ‘Your mum has been shifted to Teheran, a bigger hospital.’

“I asked about my two sisters. The nurse took me to a bed with two young girls they said were Zioło. I said, ‘They’re not my sisters. I know my sisters. They only left me about a week ago.’ The nurse said, ‘We’ll go into every room and see where they are.’

“And I went, and I think Danuta saw me and started screaming, ‘Tadzio! Tadzio!’ I said, ‘They’re my sisters.’”

Danuta: “We were separated, Alina from me, and my mother too. In the hospital, they fed us well, and gave us clothes so we could go and play in the sun.

“That’s when I saw Alina walking behind a Persian orderly.”

Alina: “He was a tall man walking in front of a little girl in a nightie and no shoes.”

Danuta: “I said to the nurse, ‘That’s my sister.’ She was only four, coming to the hospital. The nurse said, ‘Really?’ and we had to share a bed, because there weren’t enough beds. It wasn’t a proper hospital.

“Afterwards I looked up and saw Ted. He said, ‘Oh, God, I thought you were dead,’ because they didn’t have me on the list when he went to check. I was so sick and was trying to sleep, I couldn’t give them my name. They kept asking me questions, this and that, picking me up, and all I wanted was for them to leave me alone.”

_______________

On 24 March 1942, Soviet authorities in Teheran consented to a British-Polish evacuation base in Pahlevi. Previously, the Soviets had professed ignorance of the planned evacuation of Poles from the USSR port of Krasnovodsk on the Caspian Sea to Persia.9

Three reconnaissance parties in Pahlevi had made “tentative arrangements” to receive 2,500 Poles a week for an unspecified time from 27 March 1942. Instead, a “sudden change of plan by Soviet High Command” allowed only eight days to evacuate about 45,000 Poles, and increased the expected daily number of evacuees from an average of 357 to 5,625. The Soviets added to the pressure by stating in their announcement that the start date for the evacuation was to be the following day, 25 March.10

There was simply no time, attending to nearly 50,000 people, to worry about keeping families together.

The new urgency to get as many Poles out of the USSR as quickly as possible led to over-crowded shipping vessels, and the need to commandeer any available sea-worthy vessel, including fishing boats.

The second immediate problem for authorities in Pahlevi was coping with the sheer volume of first, the mainly military personnel, then the malnourished, destitute Polish civilians who needed shelter, food, and medical care. To add to the problems for the receiving centres in Pahlevi, many of the civilian Poles arrived with typhus and other diseases that they carried from the USSR, and that spread among the vulnerable.

On 25 March 1942, a ship carrying the first Polish airmen and soldiers arrived in Pahlevi from Krasnovodsk. It may have returned immediately to take aboard the 899 infantrymen from “various” units who arrived on 27 March. On 28 March, 17 vessels carried 5,062 military personnel, cadets, and nurses, and one vessel transported 70 orphans.11

Storms made some crossings over the Caspian Sea longer and more uncomfortable than others, as “evacuees arrived at all hours in [their] thousands without due notice.” A positive aspect to the inclement weather was that it discouraged the disease-spreading flies.

On 4 April 1942—the day before the last vessels crossed the Caspian with the balance of the alphabet—one of four vessels carried only “families” (1,833 adults and 1,065 children) and another carried only “civilians” (286 adults and 365 children). The final day’s five vessels’ crossings carried military personnel.

By the time the Ziołos arrived in Pahlevi, the British and Polish authorities there had developed a system to shelter the evacuees in tents and triage them through the disinfection stations, and make-shift hospitals, and move them out of Pahlevi and its Soviet influence, to Teheran. There was simply no time, attending to nearly 50,000 people, to worry about keeping families together.

_______________

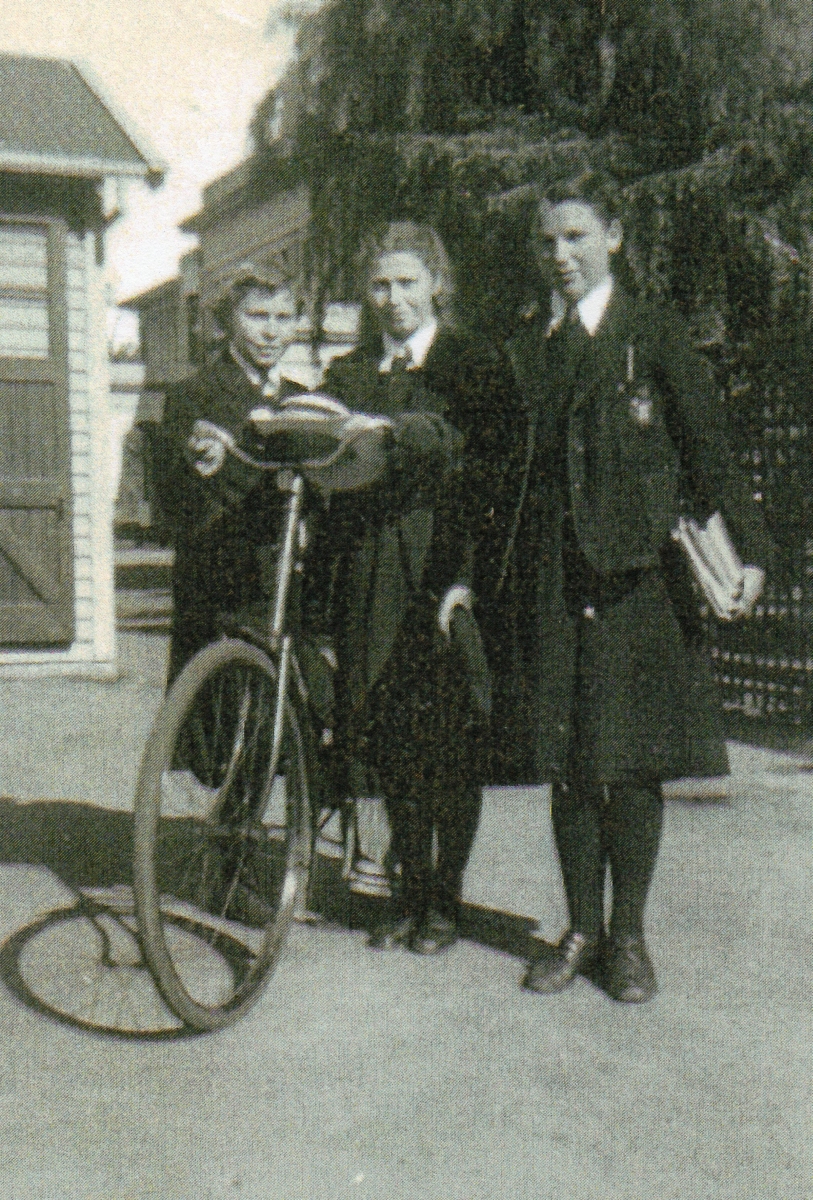

Danuta, Alina and Tadeusz in Teheran.

Tadeusz: “In Teheran I was in one camp and, when the hospital discharged my sisters, they were in another. I stayed in a big dormitory with quite a few boys.

“Mum was in hospital in Teheran about four months. I used to go every Sunday to see her after Mass and breakfast, but before I left, I went to the lady in the kitchen, who was very nice.

“She said, ‘Tadziu, I hear you’re going to hospital again.’ And I said, ‘Yes, every time I can go, I will go,’ and she used to give me a wee parcel with food. It was quite a distance to walk, so she made me something to eat on the way.”

Alina: “On one of Ted’s visits Mum said, ‘Try and find the girls. I would love to see them,’ so he went from camp to camp looking for us until he found us.”

Danuta: “It was lovely seeing Mum again.

“The hospital had two buildings, one for children and one for adults, and our mother told us she couldn’t sleep at night because the people in the ward were crying about losing their families and everything.”

Alina: “I only remember visiting her once, and all the women looking the same. White tunics…”

Danuta: “Shaven heads.”

Alina: “Yes, all shaven heads, rows and rows of single beds, and all looking the same: skinny and with the shaved hair in the white tunics. I remember a lot of them had typhoid.

“I said to Mum, ‘Where are your plaits? Where’s your hair?’ I don’t remember what she said, but she was thrilled to see us, and gave us lovely hugs.”

Danuta: “But she said the rest of the women were crying for their families, and loudest at night.

“Tadzio was getting his First Holy Communion and a lady, a neighbour from Poland, who visited my mother the night before, said that she was trying to say something, but she had trouble talking. I told Ted after his First Holy Communion, so he got a pass, because you were not allowed to leave unless you had a pass, and went to see her.”

Tadeusz: “Mum always had some lollies or something for me to take back. The last time I went, she said, ‘Tadzio, I’m coming with you next week.’ And I went the following week. The nurse told me, ‘You go and see your mum, she’s over there,’ in the morgue. She told me which one was Mum. They used to bury them in just a sheet, wrapped up, and I opened it up and Mum was there all right. It was the end.

“Later, I went to the cemetery, saw Mum’s grave, and did the same thing I did with Dad, said the Our Father and Hail Mary and Rest in Peace for her.

“It would be different if I had been younger, but Dad classed me as adult, so I had to pretend I was adult. I came from hospital and those two met me and I bought the stuff that mum saved for the week to give them, and I said I had bad news—Mum died—and the three of us cried.”

Danuta: “He came to us and said, ‘I have to tell you something but promise me you won’t cry.’ And when he said Mum died, God forbid, I cried like anything. All the girls rushed in, ‘What’s the matter? What’s the matter?’ and the guardian came. I told her and she said, ‘Next Sunday, we’ll go to the cemetery and you can see your mother’s grave.’

“They buried two people in one grave, because they didn’t have enough space. The guardian took us to the cemetery, left me with my friend, Stasia Błażków, to say goodbye to my mother, and went away with the other girls.13

“The next thing I see—a lady dressed in black. She says to us, ‘Children, why are you crying?’ We thought that she was a ghost. I didn’t see her when the guardian and the other girls were there. It was only when everybody left and I was alone with Stasia, that she appeared. We were so frightened, we ran like mad, right over the graves, to get out of there.”

_______________

The caption to this photograph in Tadeusz’s collection reads: “These orphans arrived in Isfahan from Teheran, and are being quarantined in Home no. 20. Some I know, because, like me, in 1944 they were sent… [last words missing]” Tadeusz is in the front on the right. The girl in the bonnet is between Alina on the left and Danuta on the right. The clothes that the Zioło siblings are wearing suggests this photograph was taken at the same time as the one in the aeroplane above.

With both parents dead, the Zioło siblings were moved to Isfahan and placed in separate orphanages, Tadeusz in no. 1, Danuta in no. 6, and Alina in no. 8. Alina did not see her brother and sister for most of the two years they were in Isfahan.

Danuta: “That’s what happened. Quite a few of the children, until they came to New Zealand, didn’t know they had a brother or a sister. Some of the kids didn’t even know their names.”

Alina: “I had forgotten about Tadek and Danka. I remember having malaria, and still shivering with half a dozen bańki [types of light bulbs, heated, and placed on her back], and koklusz [whooping-cough] that followed me to New Zealand.”

Danuta: “I remember one girl with malaria, shaking like anything and we covered her with our blankets, so many on top of her, and she was still shaking. There, we had a blanket for a mattress, and a pillow and another blanket to cover yourself.”

Danuta of Isfahan: “We remember the buildings and it being very hot. We were well looked after there.”

Alina: “We had to stand in a row and they gave us cubes of butter, cheese, and raw eggs to get us back to health. We had to drink the eggs in front of them.

Danuta: “We used to make kogiel-mogiel [Polish eggnog]. We had a friend who had sisters working in the kitchen. She used to get the sugar and we would mix it with the egg.

“I remember the pomegranates, beautiful and juicy. Here, a Dutch friend used to give me $10 every Christmas for three pomegranates, and I still buy them every year, even though they’re not a quarter as nice as the ones that I remember in Persia.”

The Isfahan compound Danuta was in had a chapel, which meant she saw her brother whenever his hostel arrived for Mass. Alina’s group was deemed too young to do the same. A woman who lived with Danuta had a son who lived with Tadeusz in no. 1 hostel, and sometimes took Danuta with her when she visited.

At the No. 1 hostel in Isfahan, Tadeusz is peeping over the head of the woman sitting in front in the black dress and holding her head in her hand. This photograph was probably taken at Christmastime. The high walls surrounding the compound are visible at the top right.

Danuta, left, after her First Holy Communion. “I needed my mum here. I felt so untidy next to my friend, who did have a mother. I got in trouble with the guardian because of this photo. My friend talked me into it, but when the Iranian photographer demanded money, my guardian got cross. I don’t know why, because we used to get pocket money, five shillings, so she had my money to pay for it.”

_______________

In 1943, Janet Fraser, the wife of New Zealand Prime Minister Peter Fraser, alerted him to a refugee ship docked in Wellington harbour: it was carrying Polish refugees, many children, on their way from Persia to Mexico. Mrs Fraser, who had taught orphans in Scotland, and in New Zealand had continued an interest in child welfare issues, encouraged her husband to make a similar gesture to other Polish refugees in Persia. On 1 November 1944, the New Zealand government welcomed 733 Polish children and their 105 caregivers in Wellington and took responsibility for them for the balance of the war. The Poles were to stay at a specially prepared camp in Pahiatua and travelled most of the way by train.

New Zealand made a perfect first impression on the Zioło siblings.

Alina: “All I could see were the rolling hills with the little houses, after Persia, so small and so different, and with such colourful rooves.

“To us, arriving here was the happiest time—all that green land and paddocks. Schoolchildren were everywhere, waving to us, and if the train stopped, they came aboard and gave us lollies and flowers…”

Danuta: “It was like being royalty for the day.”

Alina: “The weather was lovely and the open spaces were beautiful. None of that Persian heat. And when we arrived at Pahiatua we were shown to our dormitories—age-groups again—and it was lovely. We each had our own bed and blankets, and a little tallboy with fresh flowers that first night. Lovely. They made us so welcome.”

Danuta: “Army blankets.”

Tadeusz: “Your own bed and clean sheets. Everything was so out of this world all the time. And in the morning you’d go to the kitchen and you’d get a lovely breakfast, usually porridge.”

Now 13 and finally able to relax, on that first evening Tadeusz went to shower. On the way back, he and a friend, Roman Kołodziński, were laughing as they ran back to their dormitory.

“The housemaster saw us. He hated people laughing. He was too old for the army. He came over to Romek and said, ‘Were you laughing?’

“‘Nie, nie Panie.’ [‘No, no, Sir.’]

“He came to me, and he said, ‘Were you?’ I didn’t answer. He gave me three with the rubber hose was carrying. Then he went looking for another victim. I was still laughing. I don’t know why, but he saw me, ‘Wasn’t that enough?’ so he gave me another four. He should not have, but he did.

“I was sore. We had run in front of his room and he wanted to give us a lesson. We didn’t laugh afterwards—or run.”

Danuta: “He was removed from looking after the boys.”

The Zioło siblings attested to the varying quality of guardianship in Pahiatua.

Alina: “A lot of them weren’t married, didn’t have children and didn’t know how to look after children and their needs, especially if the children had problems. You couldn’t go and ask them to help you. It was just rules that you had to follow: shower, clean, and into bed. There were always rules, no matter what: rules, rules, rules. I think it was because there were so many of us.

“We hadn’t been there long when they gave us tripe. It smelt horrible, it looked horrible, and it tasted horrible. I tried, but I couldn’t swallow it, so I vomited, and I will never forget that lady—the guardian I had—telling me off: ‘Look what you’ve done!’ I’m vomiting, I can’t eat it, and she’s telling me off and wouldn’t let me go. I had to sit with it in front of me. I was only seven.

“Another guardian saw what was happening, came over, and said, ‘I’ll look after her.’ They had words, but I got up and went to her table.”

Danuta: “If we didn’t eat our food, we had to sit there till 8 o’clock. You had to finish your meal.”

Alina, far left, with some of the girls who have remains life-long friends. Next to her are Janka Łabędź (middle) and Hanka Jabłońska. The girl on the far left in the back row is the only one Alina can’t identify. The others are, from left Jasia Krejcisz, Genia Bełza and Jadzia Bryl.

Alina: “I knew that Ted was my brother. Later in camp, Bożena was looking after us in the dormitory one evening while the guardian went somewhere and she reckoned I was naughty. She said, ‘Get into bed Alina,’ and more, and I said, ‘If you touch me, I’ll tell my brother.’”

Danuta: “As we grew up, they were supposed to tell us about the facts of life. They never told us anything. Only, ‘Treasure your body. Don’t let anyone touch it.’ That was the only thing. [One teacher] was going to tell us something but one of the girls started to laugh, so she said, ‘You’re still silly,’ and stopped. We were 14.”

Danuta and some friends heard that same teacher say to another girl who limped and had a slight imperfection in her eyes: ‘Look at you, look at the way you walk and look at those eyes of yours.’

Danuta: “[The girl] stood there so sad. We went in to see Pani Żerebecka—she was in charge of all the girls— and the teacher got a warning from Welfare.”

Here, Tadeusz is second from the right. John Pascoe took the photograph, now lodged at the Alexander Turnbull Library, on 7 February 1945. The caption explains that the children were clothed through the Polish Children’s Hospitality Committee.14

Tadeusz, second from right, seems to be wearing the same white tee-shirt as in the photograph above, so this one may have been taken on the same day. The boys are in the camp's vegetable garden. The other boys are, from left, Stanisław Prędki, Artur Gawlik, Wacław Gołębiowski, Aleksander Basałaj, Kazimierz Depczyński, Mieczysław Sadowski, Edward Dąbrowski, and Tadeusz Budny.

Tadeusz joined the Pahiatua Scouts. He is in the middle at the back of this group, with

the head of the camp’s movement, Stefania Kozera, in the front. Standing from left at the back: Stanisław Wolk, Kazimierz

Wiśniewski, Tadeusz, Julian Borowiec, and Kazimierz Walczak.

Sitting from left: Alfred Sapiński, Mieczysław Ptak, Bronisław Rożniatowski, Jerzy Jankiewicz, Mrs Kozera, Czesław Pelc (arm

in sling), Lech Lubas, Jan Lasota, Jan Kowalski, Adam Banaś and Krzysztof Staszczuk.

_______________

The six-year age gap between Tadeusz and Alina led to more separation for the siblings in 1947. The New Zealand government faced an awkward situation with the Polish children’s camp after the Allies delivered post-war Poland to a communist-controlled government: As part of Churchill’s and Roosevelt’s deal with Stalin, eastern Poland—where most of the Pahiatua Poles had lived before the war—went to the USSR.

In 1940 and 1941, Stalin’s soldiers had forcibly removed those Poles from their homes. In 1942, those Poles had escaped from Stalin’s forced-labour facilities in the USSR. By 1946, Stalin owned their pre-war land and ruled their post-war land.

Peter Fraser’s government did the honourable thing: it offered continued residency to anyone not wanting to return to post-war Poland, but retained guardianship of the orphaned children until they were old enough to make their own decisions. Those children, however, had to integrate into the general New Zealand society.

Lessons purely in Polish changed to include English, and Catholic high schools in New Zealand received older pupils. Tadeusz and six others went to Marist Brothers’ School in Greymouth, in 1947.

As well-intentioned as the inclusion of English in lessons at Pahiatua was, many of the older students remained ill-equipped for the reality of continuing their high-school education in purely English. Tadeusz, then 16, and his Pahiatua friends floundered, and Danuta, sent to Sacred Heart College in Christchurch, “hated” the experience.

Danuta: “We didn’t know the language. It was awful.”

Tadeusz: “In Pahiatua, we learnt in Polish because we intended to go back to Poland. We had a few lessons in English, but it wasn’t sufficient for us to go to high school.

“In Greymouth, they put us in Form 3, the beginning of high school and sat us right at the back of the classroom. We had a teacher, a brother, who ignored us. He was horrible: he should never have been a teacher. To him, we didn’t exist. We never learnt anything in the classroom. Outside it was a bit different. We were good at running and shot put, and played in a few football teams. The seven of us made a seven-a-side soccer team. We used to win all the games, but we were the oldest, so it was not surprising.

“We missed out on so much high school. It was a shambles. They sent us to Greymouth because it was known for engineering. They said they were going to make engineers out of us, but we finished up as labourers.”

The seven Pahiatua boys, with three of their teachers, at Marist Brothers’ High School, Greymouth. From left, Jan Turkawka, Edward Kukiełko, Kazimierz Depczyński, Artur Gawlik, Tadeusz Rozbicki, Tadeusz Zioło and Jan Sajewicz.

“After about a year, we complained to Father Plater, our priest in Pahiatua. He came to visit us and saw that we weren’t getting any education, so he went to the Monsignor and we left shortly afterwards. The only English we learnt there was from the people we used to board with.”

The elderly Father Lawn provided the only gentle shoulder for the boys, but not in a setting conducive to general conversation. After his first visit to the confessional, holding a bilingual order of confession and list of sins, Tadeusz made a point of making sure that the kindly priest sat behind the screen.

“One side was in English, the other in Polish. I was reading from the card and he kept saying, ‘Very good, very good.” I came out and said to the boys, ‘You go to him; everything is “Very good.”’ Father Lawn was a nice fellow.”

Tadeusz left school at 17 and moved to Christchurch to be near his sisters. Danuta had at first been a boarder at Sacred Heart but became a day scholar after Father Plater’s intervention.

Danuta: “Father Plater was very good to us. He used visit every year and take us for afternoon tea, and sit and talk with us. If we had any problems, he would go to the Kiwi priest, and ask him, ‘Would you look after my girls?’”

In 1949, when the Pahiatua camp closed, Alina moved to the Ngaroma Hostel in Lyall Bay, Wellington, where she completed her primary school education. The next year, she joined Danuta at Sacred Heart, but as a boarder.

Alina, second from left, helping to wash up after a meal at the Ngaroma hostel in Lyall Bay, Wellington. The image was published in a double-page spread in the weekly news on 23 November 1949. Alina remembers Jasia Brejnakowska (now Krejcisz) and Irka Frydrych, who went to America.15

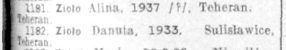

This photograph appeared in the same double-page-spread. The feature noted that it had been five years since the Polish girls had arrived as refugees in New Zealand in 1944. Alina: “That’s me [front left] pretending to play tennis. They told us to pose, but I loved playing tennis.16

Alina, left, during her first year at the Sacred Heart College in Christchurch. Danuta is next to her. With them is Alicja Głowacka, another boarder.

Alina: “There were four of us in the boarding house: Olga Sajewicz, Stasia Markowska, Alicja Głowacka and me. It was so much easier to talk in Polish with the other girls. They kept trying to separate us, but we always found a way to get together.

“I got to know Danuta and my brother once we were all in Christchurch. Tadek used to visit me with a box of chocolates every Sunday afternoon. We used to sit in the parlour and chat, I can’t remember what about, but I loved having him there.

“A nun noticed and came over to tell me what a wonderful brother he was.”

_______________

Tadeusz and friends Jasiu Sajewicz on the left and Artur Gawlik.

Tadeusz’s first job was at the Islington Freezing Works.

“That didn’t last long. I worked at the Riccarton carpet factory17 for about a year and a half, with Jasiu Sajewicz. We worked on a machine where we got better money than the others. At Christmas, the others decided we should share the money with them, so that everybody got the same.

“Jasiu and I decided that we wouldn’t work there anymore if that was the case, and we told the manager. The manager said we had to split our money. We said, in that case, we wanted to resign, but he said we couldn’t walk out without teaching someone else how to use the machine. He didn’t want to lose production.

“I was lucky, I was boarding with the Fletchers, and Mr Fletcher was a union man. I told him what happened. He said, ‘Ted, don’t worry. You can leave any time you want to.’

“You had to give 21 days’ notice. Mr Fletcher said, ‘You go in now, and tell him you’re leaving.’ It would be three weeks by the time we had to come back from the holidays, and that covered me for the 21 days. He had it worked out for me.

“I did as he said, left the carpet factory, and started looking for another job. I went to Firestone,18 where they made tyres, and asked, ‘Can I have a job?’ The American I spoke to said, ‘Yes, but you have to pass the medical first.’ I did, and took the doctor’s report back to the American, and he said, ‘When do you want to start?’ and I said, ‘Monday.’ I think it was Friday. He said, ‘Very good. You see you come here at 7.30 in the morning.’

“I had quite a long way to go by bicycle, from Riccarton to Papanui, but I was there early on the Monday. I stayed with Firestone for 38 years.”

The Zioło siblings with friends at one of the Polish dances. From left, Tadeusz, Jasia Krejcisz (née Brejnakowska), Lodzia Kołodzińska, Fredek Sapinski, Alina, Ola Sajewicz (later Wołk), Marek Kazimierzak and Danuta in front.

Tadeusz married Sylvia Horrell in February 1963. They had four children: Marianne, named after Tadeusz’s mother, Mark, Anthony and Julie.

Sylvia’s sister, Jenny, was one of Alina’s neighbours, and the two introduced their siblings when Sylvia was looking for someone to take to a herd-testing dance.

Tadeusz: “We went to the dance together and we just clicked.”

With Sylvia’s encouragement, Tadeusz asked Jan and Louise Liniewicz to be his foster parents. Tadeusz had met and “become friendly” with Jan Liniewicz through a church committee.

“Sylvie had her parents and she said it wasn’t fair that she had them and I had nobody, and her parents were too young to be my parents.”

Jan Liniewicz arrived in New Zealand as a Displaced Person from the British Zone in Germany, in 1950, having sailed from Bremerhaven to Wellington on the hellenic prince. In 1954, he married Louise Voelpel, originally from Lwów, who arrived the same year from New York.

_______________

After school, Danuta found work in a factory sewing menswear at the Lane Walker Rudkin clothing company. She later moved to Wellington, where she met and married Zdzisław Gawronek. They had two daughters, Halina and Krystyna, and Danuta returned to Christchurch after she and Zdzisław separated. He died in 2001.19

Alina also moved to Wellington after her schooling. She married Hungarian Michael Toth and had two sons, Michael (Miki) and Stephen. Alina’s siblings and Christchurch’s lower house prices brought the young family back to the garden city. Miki was not yet two, and Stephen not yet born.

After she and Michael separated, Alina worked at Lane Walter Rudkin’s administration offices; then United Bank; and lastly at the Department of Inland Revenue, from where she retired.

“I was 58 when I retired. They used to tease us by calling us call us ‘the old fossils’ or ‘dried arrangements’ but they cried and hugged us when we left.”

From left, Ted with Mark and Marianne, Danuta with Halina and Krysia, and Alina with Miki and Stephen.

_______________

Tadeusz returned to Sulisławice, with his family, in 1972.

“Firestone was opening a new factory in Kenya, and they wanted some supervisors to open it and teach the local people. The manager asked me if I would consider going, my wife and children too.

“When I got home, I asked Sylvie, ‘Do you want to go for a trip?’ I told her where and said we could take the children with us so naturally the next thing, we all got injections against malaria, typhoid, and other things, and went.

“We stayed there for two years. Before we came home, I said to the manager that I would like to see the place where I was born. Firestone paid to Kenya, and we just paid the tail end.

“The six of us went to Poland. We hired a campervan in Frankfurt, East Germany, and drove through Czechoslovakia to Poland. We stayed only a fortnight, because I was worried that the authorities might not like something and hold us back. With four children, I didn’t want that.”

Despite the underlying unease at being behind the Iron Curtain, Tadeusz felt completely at home in Poland.

“It was honestly amazing. I knew Sulisławice, and everybody knows the Ziołos there; they still have land. We are a large family and they welcomed me like a close nephew. Goodness, the hugs! Staszek, Dad’s youngest brother, still lived there.

“Uncle Staszek, said, ‘Come Tadzio, I’ll take you to where you were born, but I won’t tell you where to go. You will have to point out the place.’ And I did.

“We went inside, and when I told the kids that this was where I was born, they got so excited, they started running around, talking in English, and making such a noise that the policeman who owned the place thought it was an uprising and came out ready to fight. Uncle knew him, and said, ‘Don’t. This my nephew from New Zealand—that’s where he was born.’

“The policeman said, ‘You are lucky, because tomorrow the house is going to be demolished.’ He had built himself a new place and was bulldozing the old one so he could have a better view. It was lucky that I got there the day before it happened.

“I told uncle everything that I used to do around the farm. Seeing the creek at the bottom, I remembered the winter when flooded and the water came up almost to the house. He said, ‘Tadziu, your memory hasn’t slipped.’ It was good to go back, to be there again, a good memory.

“I asked him, ‘Are you a communist?’

“‘Yes I am, Tadek, I am. And you know why? Because I get treated better and I can also speak for others in the village. That’s why I joined the communists—because if I didn’t, I wouldn’t be able to say anything.’

“So he was two-faced. He was a Pole and he was a communist but he was well-respected, so… Of course the policeman was a communist. That’s probably why he thought there was an uprising when he heard the noise the kids made.

“He took me to visit my other uncle, Józef, in Bydgoszcz. The whole family in the campervan went up north. It was a big campervan.

“The only thing I didn’t like was when I had to drink clean vodka.

“I used to have the occasional social drink, not the real thing, but Staszek: ‘Musimy się napić, Tadek, tak długo Ci nie widziałem.’ [We must share a vodka, Tadek, I haven’t seen you for so long.]”

Tadeusz’s four children both cushioned and prevented him from asking potentially sensitive questions, such as how the rest of the family survived the war, and how they coped afterwards.

“They were more interested in what happened to their brother and how we were doing. By the time we had a drink and a bite to eat, we didn’t have much time to talk, because we had to get the kids to bed. Julie, our youngest, was only two.

“People were still living as they were living before the war. Nothing changed in the villages. There was still work. Maybe in the cities people felt the pinch—like when Gomułka took over—but in the villages, the people were still the same. Except my uncle: he was a communist but said he wasn’t a real communist, just to speak for his people. Who would know?

“From there we went to England. Sylvie wanted to show me some places she went to before we married, and from there we went to Los Angeles and Disney Land and back to New Zealand and Firestone.”

Nearly 40 years later, Danuta’s grandson, Tristram, took her, his mother, Halina, and his wife, Heidi, to the old Zioło farm in Sulisławice.

Danuta: “We went to see my uncle Juzek and he took us. The house was already gone, but we looked for the stream I remembered. When I was little, my brother was playing ball, and it went into the water. My mother ran to get it out. I don’t know if she managed, but if she hadn’t, the river would have taken it.

“My uncle told us about a cousin Nigela who lived nearby and another cousin, Marianna. As soon as you sit down, vodka is on the table, and sausages, salamis, and all sorts of things.

“It was nice to see them, because they were lovely people, but I didn’t feel anything emotional about going back. I was too young when I left.”

_______________

Five years after he returned from his trip to Poland, Tadeusz’s manager, Harry McMillan, approached him: ‘Ted, how would you like to retire?’

“‘Harry, I’ve got another three years to go.’ I was only 57.

“‘That’s all right; we can retire you at any time.’

“‘But how am I going to live?’

“‘Ted, you’ve got a good redundancy, you should be happy.’

“‘Harry, write down how much I’ll get, so I can show my wife.’

“I went home and showed Sylvie the sheet of paper. She brought me the phone:

“‘You ring them up now, in case they change their minds.’

“I worked the month out to finish my assignment.”

Being retired gave Tadeusz more time to prepare the houses they lived in for sale—the Ziołos moved 14 times during their marriage, to houses of varying sizes and sections that included a five-hectare block in Wigram, near the airport, and 14 hectares in Litview.

“In Poland I would never have had what I had here. God’s blessings got us through. In Russia, when I got typhoid, they were carrying the dead bodies out as they were bringing sick ones in. I don’t know how I survived.

“And afterwards, going to freedom—you could do what you liked—and coming to New Zealand, even better. I’m grateful that I came to New Zealand, and that it gave me opportunity, which lot of boys didn’t take.”

Ted continued to live with the Fletchers well into his 20s and his early years at Firestone.

“I was a gambler. I used to gamble on the horses. One day, I gambled that much, I didn’t have enough money to pay for my board. It was bad. The priest came over. The Fletchers must have told him that I’ve got a problem with gambling. Father Joyce came over, and they said to him, ‘Father, would you like a cup of tea?’ ‘Oh, I’d love one.’ And they left me sitting with him while they took a long time making the tea.

“He started talking with me: ‘Have you got any problems? Tell me, I might be able to solve them for you.’

“I said, ‘Well, Father, I don’t know. The only one problem I’ve got is picking horses with three legs: they can’t win races.’

“And he said, ‘I think I know what you mean,’ and he started telling me how gamblers lose their money: they think it’s their money, but it’s not, because whatever they make today, they spend twice as much next week.

“He said, ‘Ted, if I were you, I would start saving. It takes you longer, but start saving.’ The way he explained it to me was amazing.

“The next day I went to church at the Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament, which doesn’t exist anymore after the earthquakes.20 After Mass a Polish fellow come over to me, a returned serviceman, and said, ‘What’s wrong with you, Tadek?’ ‘Oh, I’m broke again.’ And he said, ‘Ted, I tell you what. You go and find yourself a house, and I’ll lend you the money to put down a deposit. I’ll show you how to do it up and you can pay me back when you’re ready.’

“And he did. He gave me ₤300, and I put a deposit on a rundown place, and I rolled my sleeves up. He came to see me there and said, ‘You are just about crying.’ I said, ‘Yes, look how much work I’ve got here,’ and he told me what to do, how to take the paper off the walls, what to do afterwards, how to put the size on. He said, ‘When you’ve finished that room, before you start another one, I’ll come over and show you how to put on the wallpaper.’

“He came again. We put one strip up together, and another one. Then he said to me, ‘Join it.’ The paper had a pattern that you had to match. It came out not bad, and he said, ‘Now, there you are Ted, that’s how you do it, but take your time and do the next one; carry on and go around the room.’

“The room wasn’t that big, but it took me two days. He came over again and said, ‘How’s it going?’ I said, ‘Have a look.’ He said, ‘Marvellous, very good.’ So from then on I started doing up places, 16 altogether, because I bought two places for my sisters but they didn’t take them on, so I did them up and sold them.

“I don’t know why he was so generous, Milczarski his name was, Józef. He had a wife and three daughters. I imagine maybe he thought one might be my wife, but it didn’t come off, because they were interested in other people. I finished up with the benefit of it. I paid him back the ₤300 with the interest. He didn’t want to take the interest, but I said I would better if he did, so he said all right.

“It all started with that priest. He was having cup of tea with us on the Friday. On Saturday he said Mass at the Cathedral, and on Sunday, it was news in the parishes that he had become a bishop: Bishop Edward Joyce.”21

Sylvia died in 2005. Tadeusz continued to live in the last house they bought together, but eventually downsized. His family has now managed to convince him to move again, closer to his children—and sisters—in Christchurch.

Tadeusz with his sons and grandsons at St Bede’s College, Christchurch, celebrating Thomas’s (left) and Edward’s (right) last day of school in 2017. Marek is far left and Antoni is far right.

Danuta: “I’m grateful for my children. I couldn’t ask for better. Krysia died from cancer four years ago, and Halinka comes to see me every morning before she goes to work, does my hair, and makes sure everything is okay, and I’ve got great-grandchildren now, one is four and a half and the other one is two.”

Alina lived “around the corner” from Danuta, and when her landlord sold her rental 16 years ago, moving even closer seemed logical. They are among five in the same complex who every year impress the judges of the Christchurch City Council’s annual gardening competition.

Alina: “I still feel very lucky. I’m so thankful that we survived all that illness when we were so young, and for all the opportunities we had here, but most of all, that I came to New Zealand with my brother and sister. It must have been so hard for children with no one.”

After 75 years in New Zealand, the Zioło siblings remain a close unit. Tadeusz is still the adored older brother, the siblings’ strength, Alina provides the sweetness, and Danuta the spice in their conversations.

© Barbara Scrivens, 2019.

THANKS TO THE TAKAPUNA BRANCH OF AUCKLAND LIBRARIES FOR THE LOAN OF AUDIO RECORDING EQUIPMENT.

UNLESS OTHERWISE STATED, ALL PHOTOGRAPHS FROM THE ZIOŁO, ZIOŁO-GAWRONEK AND ZIOŁO-TOTH FAMILY COLLECTIONS.

ENDNOTES:

- 1 - Tadeusz used the word ‘deported’ in the same way as so many of the Poles who had been forcibly removed from their homes by the Soviets in 1940 and 1941. It was Soviet terminology drummed into them and incorrect: it implies that the Poles who were forcibly removed from their homes had no right to live in that part of Poland, that they were foreigners or interlopers with no rights of ownership of their land.

- 2 - Eugeniusz Zalewski, born 1931, arrived with the Pahiatua children and his brother Mieczysław, born in 1927, joined him after the war.

- 3 - In this and other stories, I use single apostrophes to show that the ‘amnesty’ was a farce: An amnesty is defined as an official pardon for those who have committed political offences, but the Poles taken by Stalin’s Secret Police, the NKVD, from Russian-occupied eastern Poland in 1940 and 1941 did nothing to deserve their abduction to the USSR. Hitler’s invasion of Russia was what forced Stalin to turn to the West for help.

- 4 - Image from Isfahan City of Polish Children, first published by the Association of Former Pupils of Polish Schools, Isfahan and Lebanon in 1987, in Essex. The book does not attribute the mapmaker.

- 5 - See Władysław Błażków's story in the Polish Veterans section on this page.

- 6 - Despite Commitment and Efforts, Systematic Forced Labour in Uzbekistan’s Cotton Fields was Present

During the 2018 Harvest : This heading introduced an article written by Kieran Guilbert of the Thomson Reuters

Foundation, the charitable arm of Thomson Reuters, that covers humanitarian news, women’s and LGBT and rights, human

trafficking, property rights, and climate change.

http://www.cottoncampaign.org/uzbekistan-2018-cotton-harvest.html - 7 - The Zioło family were on the first of two mass evacuations of Polish soldiers and civilians from the USSR. They travelled over the Caspian Sea from Krasnovodsk (in then Turkmenistan SSR) to Pahlevi (in then Persia).

- 8 - A report, dated 3 June 1942, by Lieut-Colonel A Ross, officer in charge of the British Base Evacuation Staff in Pahlevi, complained about the high number of Poles who had contracted typhus in the USSR, bringing the disease to Persia.

- 9 - Taken from the report mentioned above, by Lieut-Colonel Ross.

- 10 - Ibid.

- 11 - Ibid, Appendix “B”

- 12 - Ibid.

- 13 - Read about Stanisława Błażków Kennedy, also in this section.

- 14 - Pascoe, John Dobree, 1908-1972: Photographic albums, prints and negatives. [Collection], PA-Group-00197. Reference: 1/4-001391-F, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, through the New Zealand National Archives.

- 15 - This photograph was part of a middle-page spread (pp. 26 & 27) in THE WEEKLY NEWS, Auckland, published by Wilson & Horton on 23 November 1949, issue no. 4487.

- 16 - Ibid.

- 17 - According to a June 2005 report, CONTEXTUAL HISTORICAL OVERVIEW - CHRISTCHURCH CITY, circa 1949,

“a large carpet factory developed, anomalously, on Waimairi Road.”

https://www.ccc.govt.nz/assets/Documents/Culture-Community/Heritage/ChristchurchCityContextualHistoryOverviewThemeIV-docs.pdf - 18 - Ibid. The Firestone factory was established close to the Papanui railway station in 1949.

- 19 - Zdzisław Gawronek's family is featured in a story on his sister, Urszula Poczwa, in the Military Cadets section of this page.

- 20 - The Catholic Cathedral in Barbadoes Street was closed after the 4 September 2010 earthquake. Two of its bell towers collapsed in the 22 February 2011 earthquake, and its future remains uncertain.

- 21 - Bishop Edward Joyce, the fourth Roman Catholic Bishop of Christchurch, was appointed on 18 April 1950, and

died in office on 28 January 1964.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Joyce

If you would like to comment on this or any other story, please email editor@polishhistorynewzealand.org.