Władysław Błażków

This story is the result of several visits with Pan Władysław between March and September 2014

at his Petone, Wellington, home. His son, Michael, joined us occasionally and arranged for me to meet his paternal aunt,

Stasia Kennedy, mentioned here and who is the subject of a separate story, i will look for

you.

Marian Ceregra, president of the Stowarzyszenie Polskich Kombatantów w Nowej Zelandii, (Polish Veterans Association in

New Zealand) introduced me to Pan Władysław after Polish Mass in Avalon in February 2014. Pan Władysław’s generosity extended

to loaning me his copies of the photographic publication 3 dywizja strzelców karpackich w

italii (3 Carpathian Rifle Brigade in Italy) published in April 1945.

All the veterans I have interviewed are heroes but the title seemed to particularly fit Pan Władysław, a quiet, gentle

man with a spine of steel. Through our conversations it became clear that during his life he did what he had to do, no matter

how tough the cost. I have valued and appreciated his company.

Pan Władysław’s journey to New Zealand lies within the context of what happened to Poles in eastern Poland after the

invasion of Russia on 17 September 1939 and the subsequent forced removal of an estimated 1,700,000 Polish people to prisons

and forced-labour facilities in the USSR. Specific historical dates are available in the military

timeline.

My appreciation, thanks and best wishes to Pan Władysław and his family.

—Basia Scrivens

Auckland, January 2015

A QUIET HERO

by Barbara Scrivens

Władysław Błażków does not need a history book to tell him when the Soviets invaded Poland. He was on border patrol on 17 September 1939 and saw it for himself.

He had been on duty there for three months. His 18th birthday came and went without fanfare on 4 September. The other soldiers with him were of similar ages, either students or military cadets with “some” military training but “not much.” If the unit had a formal name, no one told its members, conscripted in the late spring of 1939 when the Polish government acknowledged that war in Europe could not be avoided.

From the building they were occupying the young Poles watched hundreds of Russian soldiers crossing the border and unanimously agreed not to approach them.

“We were a very small group, maybe 15 to 30 of us. What could we do? We could not fight Russia. There were not enough of us. We all went home.”

Home for Władysław was a farm in nearby Berezki, a kolonia (settlement) in the municipal area of Czarnokońce Wielki, four kilometres from the Russian border in rural south east Poland. The family hadn’t lived there long—his father, Michał, had consolidated several small-holdings in 1937 and poured the profits into one large but more manageable property.

Michał was born in 1880 and lived in Prussian-occupied Poland in 1914. In World War I he was conscripted into the German Army, and transferred to the Polish Army after the Second Polish Republic emerged in 1918. After he left the military, he bought and built up several small farms scattered around Cebrów, near Tarnopol, where Władysław, his brother Bronisław and three sisters, Czesia, Kazia and Stasia were born. Władysław’s mother, Barbara, was a Greco-Catholic from the Warwaszki family.

The farmers in Berezki came from all over Poland. Władysław remembers life as good but tough, with all family members helping on the farm that sustained them. Unlike his father, growing up under Prussian occupation when all schooling was in German, the Błażków children received schooling in their own language and Michał could be forgiven if he felt satisfaction at creating a better life for them.

NKVD (Soviet secret police) agents arranged a town meeting and informed the residents they were “capitalists” and therefore needed to be “taken away.”

World War 2 put a stop to it all, although Michał and Barbara may have thought at first that because of their close proximity to the border they would remain relatively unaffected by the invasion: Once the Russian troops and tanks passed through on their way westwards, they seemed to dismiss the local people as non-threatening. Apart from the fact that their country was occupied by Germany and Soviet Russia—their particular area by Russian troops—the Błażków family’s life changed little.

“We were on a farm, Germany was so far away, there was no telephone, no communication. Everything was very quiet. [The Soviet soldiers] did not touch us.”

That initial hands-off approach did not make the 20 or so Polish families in Berezki immune from the inevitable. NKVD (Soviet secret police) agents arranged a town meeting and informed the residents they were “capitalists” and therefore needed to be “taken away.” The warning scared the Poles but did not prepare them for their capture.

_______________

Władysław remembers 10 February 1940 as a freezing winter’s night. Deep snow covered their farm. Soviet soldiers arrived early in the morning, banging on their door, shoving it open and shouting into the dark house that they were all going to Siberia. The solders’ aggression, as they supervised the family’s hurried removal from their home at bayonet-point, especially frightened the young girls.

“They told us what we could take and what do you take? So much was left behind.”

They took warm duvets (pierzyny) and some clothes that they sold months later for food. Stasia remembers her mother packing a sack of flour. The soldiers spared only two “very, very poor” families, originally from Sląsk (Silesia) in western Poland. They bundled the rest of the villagers onto horse-drawn sleds for the three to four hour trip to the nearest railway station, and transferred them to an animal transport train headed towards Siberia. Władysław does not know where exactly they went—just that after about a month the cattle train deposited them at a “large camp with many houses next to a forest.”

Władysław recalls about 16 people in the wagon. Some of the occupants were Russian civilians from the Communist Party.

“When we stopped at a station, they were allowed to get out and were given food and other things. Nothing for us.” Michał, who could speak Russian and German, said the Russians were from Kiev. They did not get off at the NKVD-run forced-labour facility where Władysław spent his days working with his parents in the forest.

“I wrapped rags around my feet and they were my shoes.”

The NKVD commandant who administered their facility created a system of work parties of five to cut various kinds of lumber. One of Władysław’s vivid memories is cutting down trees in minus 50 degrees after they had sold their clothes.

“I wrapped rags around my feet and they were my shoes.”

“If you get sick you have to go to work. If they sent you home it was all right, but if you were sick and could not get to work, you were in trouble. They came to look for you. The [NKVD] lawyer came looking for you straight away, to take you to jail.”

Bronisław, aged 13, found that trouble. While the older members of the family laboured, he and his three sisters attended Russian ‘school.’ Among the things the Polish families were forbidden to take with them to Siberia were personal photographs, documents, any kind of paper, or writing utensils.

One evening Wladisław and his parents came back from the forest to find Bronisław gone. There was no official explanation, but they gathered he had had been accused of stealing a pencil and sent to prison. A year later, still unable to find out his whereabouts, the news that the rest of the family had been granted ‘amnesty’ and allowed to leave the camp came with a bitter-sweet tinge.

_______________

They had Hitler to thank for their unexpected ‘freedom.’ The Nazi Party leader and German chancellor turned on Stalin in June 1941 and invaded Russia, using Stalin’s tactic of coming in through an open door: Hitler took advantage of his then-ally's occupation of eastern Poland, a perfect corridor with an initially unsuspecting army that could be—and was—relatively quickly overrun.

Stalin switched allegiance, joined the western allies and—once they were on the same side—saw a secondary value in the Poles already interned in the USSR: potential soldiers who could support his own Red Army troops. Forty days after German troops stepped over the artificial boundary Hitler and Stalin created in Poland in 1939, Polish Prime Minister Władysław Sikorski and Soviet Ambassador to the United Kingdom Ivan Maisky signed a Polish-Soviet Agreement in London.

The Poles in the USSR were to be released and a Polish army formed on Russian soil.

This Polish army had no intention of staying in Russia but gathered as quickly as possible, which was not quickly at all.

The vast distances between the hundreds of forced-labour facilities and prisons scattered all over the USSR, the difficulty with communicating the news of the ‘amnesty’ to the incarcerated Poles, their emaciated health, another looming Siberian winter, and the fact that the quickest form of transport—the railway network— was being used primarily for the transport of Soviet soldiers—all hampered the Polish army's formation.

_______________

“They said, ‘You’re free, go,’ and there was my brother somewhere out there.”

Władysław did not know then that his brother, under the same ‘amnesty’ and determined to reunite with his family, had started walking back to the NKVD facility. Bronisław got off a train at the same station that his parents, brother and sisters were waiting to board one.

“I was waiting for some free bread and when I got back the train was gone. My whole family was gone. I chased that train for three or four days,”

“Suddenly, there was my brother…” smiles Władysław.

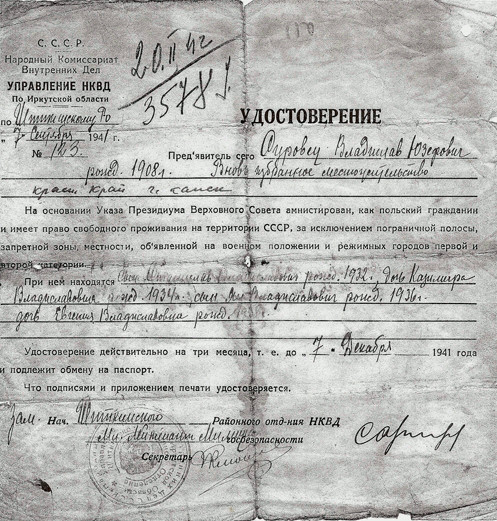

The NKVD commandants of forced-labour facilities received—but did not always follow—orders to issue the fathers of the families with papers such as the one below listing family members permitted to move around the USSR and travel by train for a stipulated time, the certificate below, three months. At first the Błażków family, unaware of the ‘amnesty’ or the forming of a new Polish army, understood only that they were somehow free to leave the NKVD facility—and did. They knew they could not survive another Siberian winter and headed south towards Kazakhstan. They had to rely on the most common mode of transport after walking—train. Potential Polish soldiers and their families often waited weeks at railway stations for trains with space for them. Eventually the Błażków family boarded one.

“There were some places where we could get supplies from the Red Cross, some free bread or meat at the stations… but you have to wait in the queue away from the stations… and it depends how long you have to wait. I was waiting for some free bread and when I got back the train was gone. My whole family was gone. I chased that train for three or four days.”

Władysław knew he had taken a risk getting off the train but had no choice: Twenty months’ forced-labour under such harsh conditions reduced his elderly six-foot father to a skeletal shadow. Władysław had to find food for the family.

The Błażkóws took two months to reach southern Kazakhstan. The Polish army's headquarters were then in Yangi-Yul near Tashkent, a few kilometres inside neighbouring Uzbekistan's border.

“I used to stay in the doorways and ask for food. A lot of the students did that. Sometimes I ate. Sometimes I didn’t.”

“We hear talk. Everybody wanted to get to the Polish army to get out [of Russia].”

The farther south they got, the larger the crowds of ragged, desperate Poles, the stronger the rumours, and the more dire the consequences of being in a place with no food, shelter or ability to work. Władysław estimates the family remained in Kazakhstan for about three months, their shelter a mud hut.

“It was a stable where they used to keep animals… four walls, one big room not properly built. The floor was the same as the street. It was all right in the good weather but when it rained, the rain went everywhere… inside, the walls, the roof, it was all the same… all mud.”

Begging became the only way to get anything to eat or drink. Władysław remembers the town as a place big enough to have restaurants.

“I used to stay in the doorways and ask for food. A lot of the students did that. Sometimes I ate. Sometimes I didn’t.”

Typhus struck the family and all except Michał exchanged the mud hut for the hospital. Władysław’s mother and sisters Czesia and Kazia did not return.

“Only Stasia, Bronek and I got back from hospital. I was back for a week and I said to my dad that I’m going to join the military. I had no choice. There was no job, no food, no one to help us, what could I do?” Although he felt wretched at leaving his remaining family, by joining the Polish army, Władysław ensured the rest of them fell under its protection and would be helped out of the USSR.

_______________

Władysław does not remember where he found the enlistment station but two days after he joined—on 21 March 1942—he was on his way to Persia (Iran).

Władysław on the far right with other trainees at a Polish army camp near the Turkish border with Iraq.

Next came Palestine. He stayed there a year before another coincidental meeting with his brother.

“One day someone told me they had seen my brother in school in Barbara [a settlement in Gaza, home to a Polish military cadet school] so I went to my officer and asked if I could go and look for him.”

Bronisław’s harsh jail sentence and sudden disappearance from the Siberian forced-labour facility had deeply affected Władysław. Back then he had given up hope of seeing his brother again and had cherished their time together after they reunited at the USSR railway station.

Seeing him was “unbelievable, twice a miracle.” Władysław beams. Bronisław, pictured left, told him he enlisted shortly after Władysław and had left Russia with the Polish army, which discovered his youth and transferred him to the Polish military cadet school [junackie szkołe] in Palestine. The brothers met a few more times before Władysław shipped to Egypt.

Władysław kept believing that his father and Stasia also survived but had no idea of their whereabouts. Many years later he found out how much his young sister had done to keep their father alive. Stasia and Michał arrived together in Teheran in August 1942 but Michał was so weak by then that Stasia was forced to say her goodbyes to him before officials took him to a hospital “to get better,” and put her into an orphanage.

Władysław is not surprised his father succumbed. It had hurt him to see how thin his father’s legs were in Siberia.

“They were as thick as my fingers. You worked in that forest, cutting it to get the logs into the river. They maybe gave you a piece of bread to eat for lunch but they wouldn’t let you stop working and there was nothing to drink.” At 62 years in 1942, Michał was a finished man.

In Palestine, Władysław joined the II Polish Army Corps’ 3rd Carpathian Rifle Division, where he trained as a gunner in the 3rd Carpathian Anti-Tank Artillery Regiment. Training for his and other regiments continued in Egypt. Their time for combat arrived in early 1944 when Polish troops landed in Italy to join the Allies in removing stubborn and embedded German units from Monte Cassino.

_______________

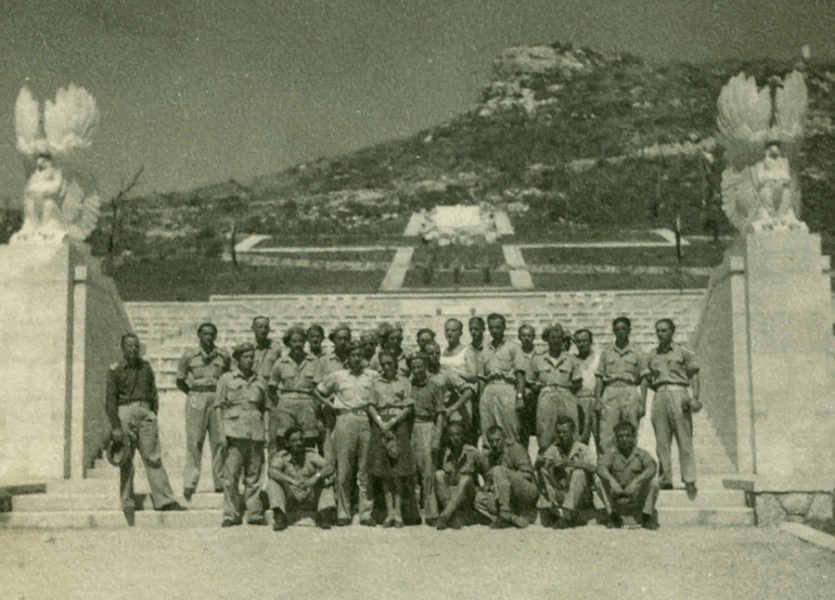

Here Władysław, left of the two at the back in the fatigue caps, poses with other members of the 96th Anti-Tank regiment, 3rd Rifle Brigade, 3rd Carpathian Rifle Division.

The II Polish Army Corps presented a military experience for Władysław vastly different from the make-shift units tasked with protecting his immediate neighbourhood’s eastern borders in Poland in 1939. Now, proper training and much better ordnance made the match of strength against the Germans much fairer.

Exchanges of machine-gun fire from opposite sides of the hills dominate Władysław’s memories of the warfare in Italy.

They reached Monte Cassino, south of Rome, in May. Allied-initiated skirmishes often took place under cover of darkness because the Germans, defending the higher ground, could see Polish positions during the day.

“In the daytime we slept, at night we battled again.”

“They don’t ask ‘How many dead?’ only ‘How many wounded?’ and we had no wounded and none dead…”

Władysław remembers one day on Monte Cassino especially clearly, still not quite sure how he survived. His regiment was positioned close to a school at the bottom of two hills. Germans were attacking from one hillside and Władysław’s anti-tank unit was protecting the Polish infantry from the other. After the previous night’s skirmishes, they remained in a precarious position, their tank exposed and without protection. They tried, unsuccessfully, to hide it in the school building.

“The Germans could see it all right.”

That particular day there was no sleep and no escape from the school building. The Germans continued firing on them as well as the Polish infantry regiment.

“We were in the middle all day, firing back.” By seven that evening, Władysław’s unit had pushed back the Germans and a Polish ambulance arrived asking for the wounded.

“They don’t ask ‘How many dead?’ only ‘How many wounded?’ and we had no wounded and none dead and after we got back [to the camp] everybody tells you, ‘You’ve got a medal,’ but only our officer got a medal for that day.” Władysław is philosophical about the outcome. Surviving such a precarious encounter with the enemy was more important to him than an extra ribbon.

One day his unit came across a suspicious truck and opened fire, causing it to drive off the road.

“We jumped into the back and there were Italian soldiers in Polish uniform, the proper ranks, everything. They were fighting the Germans in Polish uniforms.”

At the end of October 1944, the 3rd Carpathian Division was to “take” the Caminite hills and create an opening for the 5th British Army Corps to cut a road between Forli and Faenza.1

This photograph was taken in Forli, Władysław third from the left.

_______________

The Italian campaign ended and so did the war in Europe—but it became clear that the free Poland for which the troops had been fighting was not to happen. A secret agreement at the Teheran Conference in 1943 with Stalin, Churchill and Roosevelt transferred to the USSR the Polish land that Stalin's troops had invaded in 1939 and occupied until the Germans drove them out in 1941. Adding to the Polish injury was the fact that the new boundary they called the Curzon Line:

… deprived Poland of enormously rich timberfields, oil fields and the cherished city of Lwów, which not even in the partitioning of Poland had ever been incorporated into the Russian Empire.2

Lwów had been partitioned not by Russia but by the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1772-1795. The area, known as eastern Galicia, was well south of the former Russian Empire’s boundary and remained under Austrian power until World War I.

Stalin, Churchill and Roosevelt ratified their Teheran Conference agreement at the February 1945 Yalta Conference after Roosevelt gained another presidential term two months before his death. The Potsdam Conference, from 17 July to 2 August 1945, confirmed the new boundary a third time. Stalin retained his political position, President Harry Truman took the late Roosevelt’s place, and Clement Atlee replaced Churchill after the latter lost the British general election on 26 July.

The triple-handshake photograph with Truman between Churchill and Stalin was taken at the Potsdam Conference.3

The three conferences ensured Poland lost nearly half of its land to the Soviet invaders. Stalin further engineered a deal whereby western Poland, together with land taken from Germany and transferred to Poland, became another communist-run state under his influence.

Władysław and the other Poles who had fought under the motto “For Our Freedom and Yours” came to terms with the fact that their Poland no longer existed. The Błażków farm, like the property of all the other Polish soldiers from eastern Poland, now resided in Ukrainian, Byelorussian or Lithuanian USSR. Their former allies encouraged the Poles to return to the new Poland but few did. In his book an army in exile, General Władysław Anders, Commander-in-Chief of the II Polish Army Corps, noted that only 310 of those who had joined the Polish army in Russia—after surviving the Siberian gulags and forced-labour facilities—applied to return to Poland.4

The Polish troops in Italy, who refused to return to their now communist-ruled country, helped build a Polish cemetery at Monte Cassino. The proposal came from Italy’s King Victor Emmanuel after the Polish Corps’ victorious battle against the Germans in May 1944.

The cemetery’s architects were Wacław Hryniewicz and Jerzy Skolimowski and the soldiers worked under the guidance of Tadeusz Muszyński.5 On 1 September 1946 survivors formally farewelled their fallen comrades at the cemetery’s dedication ceremony.

Władysław’s regiment at the entrance of the cemetery where two white eagles—Poland's national symbol and its coat of arms—guard the graves immediately behind, and frame the cruel mountain.

At the entrance are engraved the words:

PASSERBY, TELL POLAND THAT WE FELL FAITHFUL TO HER SERVICE.

Above the cemetery, on a marble spire, are the inscriptions:

“ZA WOLNOŚĆ NASZA I WASZA”

MY ZOŁNIERZE POLSCY

ODDALIŚMY

BOGU - DUCHA

ZIEMI WŁOSKIEJ - CIAŁO

A SERCA POLSCE

“FOR OUR FREEDOM AND YOURS”

WE SOLDIERS OF POLAND

GAVE

OUR SOUL TO GOD

OUR LIFE TO THE SOIL OF ITALY

OUR HEARTS TO POLAND

The “colours of six nations that had taken part in the battle of Monte Cassino fluttered proudly in the wind” during the dedication ceremony.6

General Anders joined his men after his death in 1970 and a post-war life of exile in England. Nearby Hills 593 and 575 hold memorials to the 3rd Carpathian and 5th (Kresy) Divisions.

______________

The Polish troops stranded in Italy post 1945 had time to think about their futures. They moved to the United Kingdom in late 1946 and demobilised into the Polish Resettlement Corps (PRC). Władysław’s army friend Walerian Świerczyński encouraged him to train together as bio-nurses at a military hospital near Cambridge and the two later worked at Cambridge University. Bronisław, scouring Red Cross lists, found Władysław again and moved in with them.

The PRC were easily-recognisable on British streets, among the few to still be wearing military uniforms while they served up to two years. Here is Władysław in London.

Walerian moved to New Zealand after his sisters Janina, Jadwiga and Stanisława petitioned acting Prime Minister Walter Nash to permit their brother to join them. They had arrived in November 1944 with more than 800 other Polish refugees and had lived at the Pahiatua Children’s Camp, Janina, the oldest, as a staff member. After the post-war decisions on Poland, the sisters accepted the New Zealand government's invitation to the Polish refugees to remain.

Władysław had wanted to immigrate to Argentina but changed his mind when Bronisław found Stasia's name on another Red Cross list. He recognised the same incorrect spelling of “Blazko” that he had used when first asked by officials. Władysław had corrected the mistake.

Stasia was also in New Zealand.

Throughout their time together in the II Polish Army Corps, Walerian had encouraged Władysław to write to one of his sisters. Władysław had refused on the basis that it would be awkward if he did write and they did not get on if, or when, they eventually met.

Władysław and Bronisław arrived in Wellington on board the ss rimutaka on 25 November 1948 as part of the New Zealand government’s family reunification scheme. By the time the brothers arrived, Walerian, Janina and Jadwiga were married and living in Wellington. Stanisława boarded with Walerian on Tinakori Road, Thorndon. Stasia Błażków was in boarding school. Władysław refused his friend’s suggestion of boarding with him too (“I might not like her [Stanisława], she might not like me.”) and moved with Bronisław to New Plymouth.

They soon missed the Polish camaraderie in Wellington and returned.

Walerian’s wish for Władysław as a brother-in-law was granted in October 1949 when he married Stanisława Świerczyńska and settled down with his wife and eventually three children, Kazia, Tadzio and Michael.

The new parents with their daughter, Kazia, at a function run by the Polish Association in Wellington in 1951. At the back is Stanisława’s sister, Janina, with her own daughter, Tereska.

Władysław joined his old friend and now new brother-in-law in buying houses, repairing them in their spare time and selling them. One day he saw an advertisement for two prefabricated houses next door to each other in Petone, on the other side of Wellington harbour. The prefabrication imported from Austria introduced not only a new trend but the perfect way for Władysław to expand their own living quarters, then in George Street, Thorndon, and include other members of his wife’s family.

He was so certain they would all agree to move that he encouraged Janina, her husband Mikołaj and Stanisława to inspect the houses while he babysat the children. The deal was done, the properties in Sydney Street bought and the two families lived as neighbours for many years.

This photograph of the young Błażków family was taken by Spencer Digby Studios.

Władysław invited his sister Stasia to join them in the family home once she completed her schooling and later extended that invitation to her new husband, Irishman George Kennedy.

A well-paying job at Mobil Oil and Grease almost fell through when Władysław caught TB in 1955 and was forced off work for a year. The company accommodated his doctor’s orders for a cleaner working environment and transferred him to their laboratory section where he stayed until retirement 35 years later.

The team at Mobil Oil’s old Hutt Road testing facility in Ngauranga. Władysław is on the far left.

Władysław appreciated the company’s support when Stanisława developed multiple sclerosis. For 15 years he juggled his job, looking after younger son Michael, the hospital, and nursing his wife at home.

His bio-nursing training in the Cambridge hospitals allowed him to put into practice some of the practical skills he learnt in caring for the disabled. He fashioned devices that made Stanisława’s life more comfortable in her final years when she was only able to spend the weekends at home. The soft hoist he made, for example, allowed him to transfer her from the car to her wheelchair causing her the least pain. Władysław would leave work at 3pm on Fridays, pick up Michael from school in Wainuomata, where he lived with his sister Kazia during the week, then pick up Stanisława from hospital and do the whole thing in reverse on Sunday evenings. Stanisława died in 1985, aged 56.

In November 2014 Władysław, with two other Polish veterans of Monte Cassino, Władysław Piotrkowski and Tadeusz Knap, was received at the Polish Embassy in Wellington by the Polish Minister for the Office of War Veterans and Victims of Oppression, Jan Stanisław Ciechanowski.

They were presented with the Polish Pro Patria medal and accompanying crystal statuette of an encased Polish Orzeł Biały (White Eagle). The award was established in 2011 and given for “Outstanding contributions in perpetuating the memory of the people and deeds in the struggle for Polish independence during World War II.”

At 96, Władysław still displays the determination that carried him through so much precarious history. He still lives in his own home, with help from his family that mirrors the nurturing he gave for so long. His one public vice—enjoying the speed of his mobility scooter.

© Barbara Scrivens, 2015

Updated September 2017.

ALL PHOTOGRAPHS FROM BŁAŻKÓW COLLECTION, EXCEPT FOR THE COPY OF THE NKVD DOCUMENT AND THE STUDIO PHOTOGRAPH OF THE BŁAŻKÓW FAMILY BY SPENCER DIGBY.

THANKS TO THE NORTH AUCKLAND RESEARCH CENTRE IN THE TAKAPUNA LIBRARY FOR THE LOAN OF AUDIO RECORDING EQUIPMENT.

ENDNOTES:

- 1 - Anders, Lt-General W, CB, An Army in Exile, originally published in 1949. Reprinted by The Battery Press, Nashville, ISBN: 0-89839-043-5, page 234.

- 2 - Bliss Lane, Arthur, US Ambassador to Poland 1944–1947, I Saw Poland Betrayed,was originally published by The Bobbs-Merril Company, New York in 1948, 57 … 81.

- 3 - http://www.trumanlibrary.org/photographs/view.php?id=588

- 4 - Ibid, Anders, page 287.

- 5 - http://www.montecassino.org.pl/cmentarze_polski_na_montecassino.php

- 6 - Ibid, Anders, page 285.