Władysław Piotrkowski

This story is the result of several interviews I conducted with Władysław Piotrkowski between September and November 2014 at his home in Lower Hutt. With us was Pan Władysław’s wife, Anna, whom I interviewed separately (see pahiatua stories).

When I first met Pan Władysław and Pani Anna in March 2014, Pan Władysław said that the history had already been written. I agreed that versions of their history had already been published but said that I believed in the importance of stories from ‘ordinary’ people. We spent the afternoon discussing aspects of Polish history and our Polish backgrounds, and they agreed to share their personal recollections of their journeys from eastern Poland to New Zealand.

It has been a privilege to spend time with Pan Władysław and Pani Anna. Their quiet courage and dignity never wavered. Their home is one of typical Polish hospitality and while sharing meals around their kitchen table I felt the smiles of my late babcia, a former professional cook. That hospitality never wavered, even as Pan Władysław's health deteriorated. His pain could not dull his wicked sense of humour. Pan Władysław died peacefully on 1 February 2015 at his home and with his family, 66 years to the day after he first set foot on Wellington soil.

This account reflects what happened to Poles in eastern Poland after the invasion of Russia on 17 September 1939, and the subsequent forced removal of an estimated 1,700,000 Polish people to prisons and forced labour facilities throughout the USSR. Specific historical dates are available in the military timeline section of this page.

I remain grateful for the time I spent with Pan Władysław and know that he is missed. Years later, his presence remains.

—Basia Scrivens

LUCKY MAN

by Barbara Scrivens

Daring to relax and enjoy the Italian sunshine one afternoon in May 1944, cost two young Polish soldiers their lives.

Five had been sitting on their soil bag reinforcements, appreciating the quiet after a series of skirmishes on Monte Cassino. The German machine gunners responsible for the two deaths also wounded two others—one so badly he could not return to active service.

Twenty-year-old Władysław Piotrkowski walked away dazed but unscathed.

Earlier, the Polish soldiers had filled the soil bags and built them into protective ‘walls’ for their mortars. As they waited for their next orders, “suddenly the Germans were firing in front of us, maybe about 100 metres away, maybe not even that, maybe even 50 metres…”

It was a lesson on never dropping one’s guard on the battlefield, and the first of several escapes for Władysław. Others in his unit considered him lucky and, by the end of the Italian campaign, Władysław believed it himself.

“I came through it without even a scratch. Once, my helmet was hit with a piece of shrapnel, but it didn’t go through. There was just a dent. A radio operator, who [later during the Allied advance] passed on my messages about where to fire, said he’d dig the trenches for us both as long as he could be with me. I thought, ‘Maybe I am the lucky one and maybe he is not…’ but we both got through.”

The Germans had thwarted three previous Allied attempts to gain control of the hill.

The hillsides below and surrounding the ruins of the Monte Cassino monastery, on its own 500-metre rocky outcrop, became familiar to the soldiers of the II Polish Army Corps as they fought German formations—including the elite 1st Parachute Division—for possession of those ruins.

By holding the elevated and strategically significant Monte Cassino, the Germans prevented the Allies from getting to Rome. The hillside formed part of the so-called Gustav Line, which ran from the Tyrrhenian to the Adriatic seas and followed the rivers Garigliano, Rapido and Sangro.

The Germans had thwarted three previous Allied attempts to gain control of the hill. Joint forces from America, Britain, France, Morocco, Algeria, New Zealand, Canada, India, Nepal, South Africa and Australia had failed to dislodge the Germans before commander of the British Eighth Army General Sir Oliver Reese gave the II Polish Army Corps permission for an assault.

American and French troops began the battle for possession of Monte Cassino in January 1944, but retreated after severe losses. Faulty Allied intelligence assumed the Germans were using the monastery as a base. On 15 February 1944, 229 American bombers peppered the monastery with more than a thousand tonnes of explosives and incendiary devices.1

The decision to bomb the monastery was not unanimous among Allied commanders, who afterwards discovered that its resident monks were guilty only of sheltering tenant farmers and their families. The surviving monks and civilians left. The Germans took the gift, moved up the hill, and made full use of the ruins’ perfect cover: two subsequent Allied attempts at assaulting the monastery directly did not work.

Polish military command, led by Lieutenant-General Władysław Anders, knew they needed a more cunning tactic to capture the high ground, link with the British forces in the valley below and isolate the Germans in their perch. They had to secure the hill, known as 593, behind the ruins.

Hill 593 appears in the photographic publication 3 dywizja strzelców karpackich w italii (3rd Carpathian Rifle Brigade in Italy) published in April 1945.2

The II Polish Army Corps was transferred to the Monte Cassino sector between 8 and 17 April 1944. The 5th (Kresy) Division and the 3rd Carpathian Rifle Division had orders to capture Hills 593 and 569 via the nearby Albaneta farm, which the Poles used as a base from where to mount their attack. With other Allies in adjacent positions on surrounding hills, the Poles went into the fourth battle for Monte Cassino at nightfall on 11 May 1944, and remained until the hill and the monastery ruins were “cleared of the enemy” on 19 May 1944.

The ruins of Monte Cassino seen from Hills 593 and 569.3

Władysław served in the 3rd Carpathian Field Artillery Regiment’s Fourth Company, a heavy machine gun unit that converted to heavy mortars. During his first battle at Monte Cassino, he did not fully comprehend its reality.

“I thought it was an exercise. Well, when we were training we were firing just like that, and we did it so often that when I was attached to the infantry I thought it was just another exercise.” He shook his head at being “young and stupid” but soon learnt ways to stay alive.

Two of Władysław’s army badges. The distinctive Christmas tree integral to the division’s insignia represents the pine forests of the Carpathian Mountains that stretch along southern Poland.

The Germans’ superior position meant they easily saw their attackers over the battle-desolated terrain. By day the Polish soldiers tried to camouflage themselves but, after given the job of directing fire, Władysław seldom joined them. Through his binoculars, he constantly watched for signs from the Germans. When he saw movement—depending on the situation—he instructed his radio operator to send a message to his superiors, or the men behind the mortars. Firing meant giving away the mortar’s position so swift responses were crucial.

“When they’re firing, you can see where they are coming from and you make no movement because they can’t see you in the dark.”

“The artillery opens fire, the mortars open fire, you go on the attack, but the Germans were waiting for you. They shoot, but you jump and you dive, and so it goes on and on, and soon you are mixing with bodies. Before the attack there were so many men, and afterwards you see that this one has been killed, that one has been killed, that one is being sent to the hospital and so on…”

Ambulances taking away the injured became targets when each side realised the other was using their medical vehicles for transporting ammunition as well as men.

Ammunition, food, and water supplies usually arrived under cover of darkness, but that darkness could not be guaranteed.

“From four or five kilometres away, the Germans would fire rockets that would light up everything and you know that as soon as the rockets dull, you run. When they’re firing, you can see where they are coming from and you make no movement because they can’t see you in the dark. You soon learn when you can move—and particularly how to preserve your life.”

_______________

By the time the Poles arrived at Monte Cassino the Italian population had long-vanished. Władysław, a farmer’s son, saw signs that stock had recently grazed on the flatter areas. Amid the detritus of previous campaigns, he noticed burnt tree stumps in orchard formation, abandoned farmhouses, and even the remains of potato crops.

Some of the dugouts made by the Polish Lancers at San D’Onofrio, between the monastery and Hill 593. It is part of another photograph that appears in the 3rd Carpathian album. 4

Front-line troops like Władysław became adept at creating a relatively safe place to rest—if not sleep—during protracted battles. Sometimes it meant digging into the hill. Sometimes one side of the hill gave protection, and the other had to be constructed. Soldiers filled their bags with any available soil and rocks, building fortifications for their “divisional assets” first, then for themselves.

One night Władysław and his companions, sleeping in such a two-roomed bunker, “woke with so much noise… a German artillery exploded on the other side [of the soil bag wall]. It missed a direct hit on our mortar… still useable, but another metre and it would have been us in our sleeping quarter.

“Sometimes when we went on the attack—like in Bologna—we didn’t even have the bags. Quite often we were in the field with nothing for shelter, not even trees.”

_______________

The Germans called Monte Cassino “The Gate of Rome.” The Poles smashed it open on 18 May 1944. By then most of the surviving Germans had retreated several kilometres north to the Hitler Line, an offshoot from the Gustav Line that ran through Piedemonte (now Piedimonte San Germano) towards the Tyrrhenian. The Germans left behind about 30 wounded soldiers to defend the monastery.

On 18 May 1944 the Polish 12th Lancers hoisted one of their pennants over the monastery ruins until someone found a Polish flag that, according to General Anders, was raised at 10.20am. An hour later, General Oliver Leese, commander of the Eighth Army, arrived at General Anders’ headquarters “and was the first to express his appreciation of the Polish achievement.”5 Soon afterwards the British Union flag flew beside the Polish one.6

What is believed to be that 12th Lancers’ pennant found its way to New Zealand. On the 25th anniversary of the Polish victory at Monte Cassino, a story with a photograph in the evening post explained: New Zealander AE Curry, from a divisional postal unit attached to the British Fifth Army, walked with a friend through the ruins the day after they had been captured. He picked up the pennant, apparently still attached to its shattered flagpole. Curry said the pennant lay in a drawer for years until he re-discovered it and presented it to the Stowarzyszenie Polskich Kombatantów (Association of Polish Combatants) in Wellington. The SPK had it mounted and displayed at the Dom Polski (Polish House) in Newtown, Wellington.7

Polish-German confrontations continued. As the Germans retreated, first behind the Hitler Line then farther north in Italy, they left behind blown-up bridges and mined roads, river edges, and fords. The II Polish Army Corps’ “Theatre of Operations” after Monte Cassino and Piedemonte included pushing through the Gustav-Hitler line; the battle for Ancona, where they acted as rearguard for the Eighth British Army; action in the northern Apennines and the Seino river; and their final battle for Bologna and the Lombardy Plain.

Władysław’s conduct in battle at Bologna earned him the Krzyż Walecznych (The Polish Cross of Valour).

This photograph of Wladysław, far right, appears in the 3rd Carpathian photographic collection’s nad adriatykiem section and was taken in action as he set the distance on the 4.2-inch mortar.8

By the time the photograph above was taken, the II Polish Army Corps had pursued the Germans up the Adriatic coast and had crossed the Chienti river near Civitanova Marche. Positioned two or three kilometres from Loreto, Władysław had noticed a German boat escaping between the rocks off Ancona, and directed his mortar fire towards it.

“Mortars aren’t as precise as anti-tank guns, and we didn’t manage to hit it, but the anti-tank unit noticed where we were firing, shot two shells, and sank the boat.”

It was the last time Władysław shot mortars. After that, his job was to direct fire.

_______________

Władysław had no idea, when he joined Nisko military school in 1939, that he would follow the family tradition of fighting for one’s country outside its borders.

His father, Jan, had been living in America when he volunteered for the French forces during World War I, and earned several French medals and promotion. After Polish independence in 1918, Jan Piotrkowski fought the Bolsheviks in the 1919–1920 Polish-Soviet War and was awarded the Wojenny Virtuti Militari (the Polish Cross of Military Virtue).

He joined the permanent Polish forces and employed a manager to care for the land that the Polish government granted him and thousands of other Polish war volunteers after the 1921 Treaty of Riga ratified the new Polish-Soviet borders. Jan’s failing health forced him to retire to his land, in Bajonówka, about 12 kilometres from Równe in eastern Poland’s Wołyń province.

This Piotrkowski family photograph was taken in 1934. Władysław, the eldest child, then aged 11, is on the left next to his maternal grandmother, Eleonora Tyszka. His mother, Zofia, is on the right. Jerzy, then nine, is in front of his father, Jan, and Zbigniew, then six, is in front. Maria Eleonora Piotrkowska was born in 1937.

Władysław’s mother filled the back of the photograph, which she had had enlarged in New Zealand for Maria’s 40th birthday, with hand-written notes on the family. She outlined her husband’s military service. She said she was the great-granddaughter of Marian Potocki, who was born in Ostrów Mazowiecka, as was she, her sisters and her brother (all unnamed). The Tsar had confiscated all her great-grandfather’s property. (From 1795, until Polish independence in 1918, the Russian Empire had partitioned that part of Poland.)

Zofia described Marian Potocki as an insurgent who took part in the 1863 Uprising, for which he received a 25-year sentence and torture in Siberia. It is not clear whether he served his entire sentence, but Zofia said that he returned home and lived “only one more year.”

Zofia, born in 1905, told her children the story of how her father, too, refused to bow to Russian tsarist rule, and how it led to her whole family being banished to Siberia, and his death aged 52.

The bulk of her writing on the back of the photograph described the Bajonówka settlement, 13 kilometres from Równe and next to the more established Krechowiecka. She thanked the army of General Józef Haller and the “entire Polish population” that fought with Haller’s soldiers, “even school girls and women,” to gain Poland’s freedom from the Bolsheviks and Muscovites in 1920. She was especially proud of the “beautiful church” the local settlers had built in Krechowiecka, “just finished and adorned” with a painting of Our Lady of Częstochowa set in gold and silver, when WW2 started.

_______________

Jan and Zofia Piotrkowski’s Bajonówka farm was typical of the area—self-sufficient, and included an orchard. Their children started their education at the two schools the settlers had built in Bajonówka and Krechowiecka.

“When war broke out the [Nisko] school ordered the older boys to go to the army to fight, but because I was 16, I was sent home.”

Władysław returned to an uneasy life under Russian occupation on the Soviet side of the geographic division of Poland that Hitler and Stalin gerrymandered seven days before the German invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939. Once the Soviets invaded Poland on 17 September 1939, all schooling in the area stopped. As the Russians emptied Polish shops and gave local Ukrainians power to seize Polish goods, Polish farmers had little incentive to continue working their land or harvesting crops.

Jan took the family to stay with his sister in Równe, and soon afterwards escaped with Jerzy westwards to find the Polish army. The adults did not involve Władysław in the decision, but he believed that his father felt that he, as the oldest son, was capable of looking after the rest of the family. They stayed in Równe for “two or three months,” then returned to Bajonówka.

The strain of living on the farm without Jan escalated in the early hours of 10 February 1940. Harsh knocks at the door revealed a Russian NKVD9 officer accompanied by six Ukrainian militia members with red bands around their arms.

“They made us hurry up and get dressed and said we should put some things in our suitcases, or whatever bags we could carry. That was it. We left everything else behind.”

The unwelcome intruders led the fatherless family away at gunpoint and bundled them onto a sled bound for a railway station. Władysław did not recognise any of the Ukrainians, but identified the Russian through his inability to speak Polish. He found out later that local Ukrainians accompanied NKVD officers from house to house in Polish villages, and helped to evict thousands of Polish families in the same way.

Władysław’s grandmother lived in the original farmhouse after his father built a new one. Whether the Ukrainians and NKVD officer did not know of other people on the property, or whether they did not see the other dwelling, they did not approach the old woman or her visiting daughter, who both remained in Poland throughout the war.

Władysław became aware of the scale of the Soviet operation when he saw the crowds gathered at Szepetówka railway station. About 40 kilometres inside the USSR, the railway hub was used to re-adjust the trains for the wider Russian tracks.

_______________

Their train eventually disgorged nearly 4,000 Poles into an NKVD forced-labour facility deep in the taiga forest.

“… the more you cut, the more you got paid… If you had money, you could get something to eat. If not, too bad…”

“In not quite two years, there were about 1,300 of us left. They died mainly from hunger. Every day you see horses pulling carriages taking coffins to the cemetery, 12, 15, 20… Every day.”

The coffins looked “ordinary but professionally built” from timber planks produced at the facility’s mill. The corpses had the temporary dignity of coverage for their final earthly journey, but not for burial.

“A coffin was emptied and came back for another person, and another person…”

Life in the facility was distilled into its most basic form: one worked; one was paid according to how much of the designated quota one achieved.

The Soviets lived by quotas and the NKVD commandants of the forced-labour facilities needed all the labour they could get to achieve their own numbers. Stalin’s latest Five-Year plan included included completing the vast railway network vital for the industrial growth of the USSR

The facility holding Władysław, his mother, brother Zbigniew (12) and sister, Maria (3), supplied timber for the railway and Soviet army. At 17, and the only provider for his family, Władysław worked as hard as he could to get maximum payment.

“They came around to check how much you had cut, and the more you cut, the more you got paid. Not very much pay, but you could buy bread from the shop, or a meal in a type of restaurant they had. If you had money, you could get something to eat. If not, too bad…”

Władysław’s conscientiousness and eye for being able to pick out the best trees to cut caught the eye of a Polish supervisor, a former forester, who offered him a job marking trees for optimal use.

“I was cutting the trees, and learnt what was inside them, and knew which one was good only for firewood and which one was good for guns or plywood. You come to a tree and you look at it, see what the bark is like, how many of the branches are dry. When you have to work to survive, you learn quickly, very quickly.”

The Polish forester who gave Władysław the job said he needed someone to carry the ink and a plane to make the markings, and Zbigniew became the family’s second wage-earner.

“I would come to a tree and decide it would produce, say, three metres for guns and five metres for plywood and Zbyszek would paint the notice on it.”

The turn of fortune gave the brothers the opportunity to travel to nearby villages and overnight in Russian homes.

“We would take something with us that they couldn’t get from their shops and they would feed us and give us potatoes, meat or milk to take back with us. We were very lucky.”

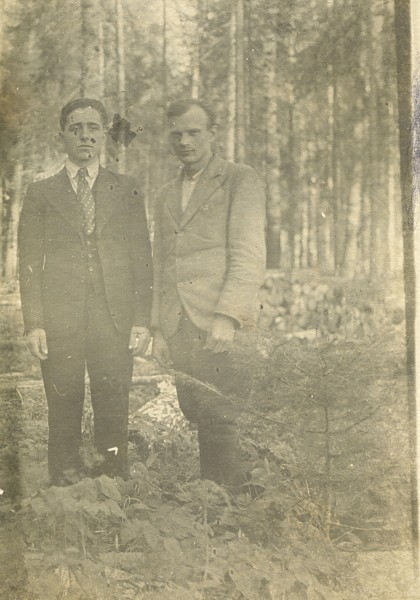

Władysław (left) with a friend at the edge of the forest surrounding the NKVD forced-labour facility. He believed the photograph was taken soon before they left because neither was dressed for work.

On warmer days, Władysław wore a hat covered with mesh to protect him from the clouds of mosquitoes that blighted the labourers.

“You couldn’t get rid of them unless you burnt something to make smoke. Then they would fly away. Otherwise, they gave you hell.”

The specific name of the forced-labour facility that held him and his family remained a mystery to Władysław, but he believed it was in the southern reaches of the Ural Mountains, and near enough to other facilities for a rumour to filter through, soon after 30 July 1941,10 that a Polish army was forming in Russia. To verify what could have been conjecture, the inmates collected “some money” for delegates to travel to Bukhara in Uzbekistan, where the Polish army had supposedly set up an enlistment station.

They came back with news: German troops were heading towards Moscow; Polish Prime Minister General Władysław Sikorski had made a deal with Stalin; an ‘amnesty’11 had been granted to all Poles in the USSR; a Polish army was indeed being formed on Russian territory.

“There was no real age limit, people from 16 to 60 joined. The point was… to help people survive, to get them away from Russia.”

The delegates also found out that special trains were being made available to take the Poles from the forced-labour facilities to enlistment stations in Uzbekistan, which led to a further collective decision to charter a train. With nearly three quarters within their facility dead, those who remained feared that they would not survive another Siberian winter, and were relieved to hear that the new Polish army had few enlistment restrictions.

“There was no real age limit, people from 16 to 60 joined. The point was not to join the army to fight there and then. It was to help people survive, to get them away from Russia. After we got to Iran, Iraq and Egypt, then we got exercise and training.”

In Bukhara, Władysław left his mother with Zbigniew and Maria in a civilian camp and walked 30 kilometres to the nearest military camp. All four left the USSR via the Caspian Sea in mass evacuations organised by the Polish army in 1942.12 Judging by the speed with which the Piotrkowski family managed to leave their NKVD facility, the photograph below, of Władysław in Iraq, and Zofia’s ability to find employment afterwards, all four were probably in the first evacuation.

Zbigniew joined the junaki (Polish military cadets) and spent the war in Palestine and Egypt. Zofia became a housemistress at a Polish orphanage in Isfahan, Persia (Iran) and kept Maria with her.

Władysław (left) and two other enlistees at a Polish military camp in Iraq in July 1942.

The Poles who joined the Allied forces in 1942 had the same mission as those who had resisted the German and Russian invasions in September 1939—to free their homeland. Until the 1918 Treaty of Versailles, parts of Poland had been lost to occupying powers for 146 years, and the entire country had disappeared geographically for 123 years. Poles had enjoyed only 18 years of full independence before the 1939 invasions, and embraced the mantra “For Our Freedom and Yours.”

Władysław first saw General Anders in Iraq.

“We had a parade because he wanted to see the soldiers and let the soldiers see him. He wanted to look into our eyes but it took him so long… and in the heat… the soldiers were fainting.”

General Władysław Sikorski showed a different leadership style. For his introduction to the troops, he stood in a jeep and was driven around the parade ground.

“It took him 20 minutes. They were two different people.”

General Sikorski died when his aircraft crashed in suspicious circumstances off the Gibraltar coast on 4 July 1943.

_______________

Two of the II Polish Army Corps soldiers with Wojtek, the brown bear who became the most unusual Polish enlistee.

Wojtek gave the troops much-needed entertainment relief and help before, during, and after their Italian campaign. Talk of the bear prompted Władysław to remember the troops’ refrain:

…Ja niczego się nie boję

Choćby niedźwiedź… to dostoję…

(… I’m not afraid of anything

Even a bear… I will withstand…)13

Władysław remembered how Wojtek enjoyed games such as ‘wrestling’ with the men, and as soon as he saw the soldiers getting ready for a swim, he would wait at the truck.

“He’d be standing there, watching everybody…”

The same men appreciated the morale boost their bear gave them when it became obvious that Poland’s so-called Allies had sold them out to Stalin.

Roosevelt and Churchill promised Stalin—as early as December 1943—the same half of Poland that his troops occupied in 1939. The ‘Big Three’ met in Teheran while many of the Polish civilians who had escaped the USSR still lived in tented camps in the same city. (See Wisia Watkins’ story, seeing stalin.) Roosevelt and Churchill repeated their pledges at Yalta in February 1945. Their replacements ratified the deal in Potsdam in August 1945, and Poland officially lost her freedom to a Soviet-controlled communist puppet government.

Poles living in Poland at the time may have had no choice regarding whether to remain, but those outside did. Most of the II Polish Army Corps’ soldiers in Italy chose not to return. They shared an added lack of motivation—their family farms fell within the USSR’s new borders.

Members of the 3rd Carpathian Rifle Division enjoy their 1945 Easter breakfast. Władysław is standing at the back on the left.

As well as the Krzyż Walecznych, Władysław received the Polish Monte Cassino Cross and four British war medals, the 1939-45 Star, the Italy Star, the Defence Medal, and the War Medal (1939-45).

The awards were no compensation for his country’s lost freedom.

“When we were fighting, it was for everybody’s rights, Poland’s, Italy’s—freedom for every country. We did not know what [Stalin, Roosevelt and Churchill] were planning at their meetings. It was only after they were finished that we found out what they did.”

_______________

At the end of the war in Europe, the II Polish Army Corps’ 112,000 men in Italy, still under British command and responsibility, became a “problem” for the British government. Despite the pressure to return to Poland, only 310 of the soldiers who had come to the corps through Russia applied for repatriation. Of the 14,200 who did return to Poland, 8,700 had ‘joined’ the corps after the German defeat.14

The Polish troops became an unwanted post-war expense for a British government feeling the financial strain of reviving its economy, and a regular subject of speeches made in the House of Commons during 1946. On 20 March 1946, British Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, Ernest Bevin, acknowledged the Polish accomplishments:15

I feel sure that the House would wish me to pay a tribute to the magnificent services which these forces of one of our first Allies in the late war, have rendered to the common cause throughout the whole long struggle. His Majesty's Government and, I am sure, the whole House, are conscious of their debt to these men and are determined to deal justly by them.

His praise for the Polish troops came after he introduced his speech with:

While we will not use force to compel these men to return to Poland, I have never disguised our firm conviction that, in our view, they ought to go back in order to play their part in the reconstruction of their stricken country…

…and that the British government considered it was the…

… duty of all members of those [Polish] Forces to decide now to return to their own country.

Bevin later answered his predecessor, Anthony Eden, regarding a possible future of Poles in Britain:

We are extremely anxious that the Polish troops should return to their own country. Subject to that, we cannot relieve ourselves of responsibility for those who feel in their conscience that they cannot go back.

One of the last direct messages from Bevin to the Poles:

Speaking on behalf of the British Government, I declare that it is in the best interests of Poland that you should return to her now…

The bulk of the Polish troops remained unconvinced. Besides military personnel in Italy, there were other Poles who completed active service in liberated western Europe, and Polish military cadets like Zbigniew in the Middle East.

_______________

It took the British government until 1947 to pass a Polish Resettlement Act that provided “certain Polish Forces” with an Assistance Board set up to meet their “needs,” including “accommodation in camps or other establishments,” “health and educational services,” and “emigration expenses.”16

A Polish Resettlement Corps gave Polish soldiers and military cadets two years to demobilise and adjust to life outside Poland. It was in Britain’s interest not to flood their fragile post-war labour market with thousands of Poles still learning the English language. Those able to get “approved jobs” started immediately. Others did “productive work such as reconstruction” or trained “for civilian employment pending their eventual return to civil life.”

Meanwhile, the families of many of those Polish service men and women still lived in refugee camps set up and administered by the British in Commonwealth countries in east and southern Africa, India, and in Mexico. Following the Mexican government’s humanitarian gesture in 1943, the New Zealand government independently set up a Polish refugee camp in Pahiatua. In 1946 the same government, after it became clear that there would not be a free post-war Poland, gave the Pahiatua Poles the option to stay.

Zofia and Maria Piotrkowska, among more than 800 Polish refugees who arrived in Wellington on 1 November 1944, chose to stay.

While British politicians argued about his fate, Władysław received a year’s training at an electro-technical school in Ascoli Picento. He appreciated the sophisticated Italian machinery and skilful teachers.

“Italian was an easier language than English and technical terms are nearly the same in any language. We had our own [Polish] technicians to help us and we learnt by working on all the turning machines, making screws, welding, and becoming comfortable with electronics.”

Polish soldier-students in Ascoli Picento. Władysław is at the back left.

Władysław with two student friends in Italy. He remembered the man immediately behind him as Nasikiewicz.

As they waited for British politicians to decide on their futures, Polish troops made the most of Italian sunshine and hospitality.

Władysław wanted to continue the electro-mechanical course in Italy but the Polish Resettlement Corps had by then arranged temporary housing in the UK for the Polish soldiers and cadets. At least 170 vacated army and air force barracks, scattered on the outskirts of towns all over England, Scotland and Wales, became their own versions of “Little Poland” after mothers, wives, brothers and sisters joined their fathers, husbands and siblings.17

Władysław was assigned to a camp in Bowers Wood, near Beaconsfield, and soon found a job as a machinist at a wallpaper-printing factory.

_______________

Władysław’s arrival in New Zealand was “pretty simple.”

Earlier, Zbigniew found and joined his brother in England. The Red Cross helped separated family members find one another and, although physically parted from her sons, Zofia had corresponded with them regularly. After the war, the New Zealand government allowed the families of the Pahiatua Poles to join them. Zbigniew, and 12 other Poles, arrived in Wellington on 28 July 1948 aboard aboard the ss rangitata. Władysław was among four Poles who travelled from England on the ss tamaroa, which docked in Wellington on 1 February 1949.

Zbigniew then lived in Petone and Władysław took a room in the same private accommodation. Within two days he had a job at an Austin assembly factory, but he soon tired of the commute and looked for employment closer to home. That came in the maintenance department at the Godfrey Phillips tobacco factory.

“On Saturdays they quite often did jobs like cleaning or fixing any problems on the machines. I was there one Saturday when the manager of cigarette production came down because a chain had broken on a machine. The fixed the joint and they put in the motor again, but when they started the machine, they couldn’t get it to reverse. They tried this and that, but whatever they did wasn’t working.

“I could hardly talk in English, and couldn’t write it, but he said, ‘Oh, I understand what you’re talking about…’”

“I watched them and, because I was in the electro-technical school, I saw the problem. I went up to them and couldn’t say very much [in English] but explained about the two wires… change the wires this way and it will go backwards, as simple as that. They changed the wires and—relief—the machine worked again. That manager, Mr McFarland, told the foreman that he wouldn’t mind having me on cigarettes—I was in tobacco at the time—and I was thinking, ‘I’m still young, I’ve had no training, it’s better pay…’

“And that’s how I got the job in cigarettes, learning the two types of machinery, old and new. I liked both of them and after a year, they said I was so good they would like me to be a foreman. I told them I couldn’t accept it because I didn’t have the language. I could hardly talk in English, and couldn’t write it, but he said, ‘Oh, I understand what you’re talking about, and we will give you a secretary to do the writing.’

“There were 40 people on the floor. Some of the old hands didn’t like it that I was foreman but in Ascoli Picento I had learnt with tools on every type of machinery so when it came to the mechanics operator job, I learnt very quickly.”

Władysław chuckled at his naivety after taking the job and his manager’s advice:

“He said to me, ‘You’ve got to be tough on them.’ I was—for the first week—but they were doing everything against me, and I knew it wasn’t working, so I changed my tune, and was good to the workers and good with the bosses.”

The young Pole gained a reputation for his honesty and willingness to accept the blame for things that went wrong. The managing director arrived every morning to inspect the cigarettes on the belt. One morning he noticed that every cigarette had the print showing the same way. He told Władysław, “You’d better fix that.” Władysław, whom New Zealanders called Warwick, agreed, and sorted out the offending oval filters.

His employment position changed when Godfrey Phillips announced it was moving production to Titahi Bay in Porirua. Managers suggested to the permanent staff that if they owned their own homes they should sell and move. Władysław did as advised but the company overturned its decision and gave its production to a firm in Petone, Wills, rather than build a new factory. Władysław was suddenly out of a job and with a house on the outer suburbs of Wellington.

The two problems resolved themselves together: The new production firm, short of mechanics, offered him a job, but selling in Titahi Bay was not as easy as it had been in Wellington and Władysław was reluctant to accept the position.

“In the end the director from Godfrey Phillips said they would buy the house if I would get a valuation, so I did, took the job, and moved to Lower Hutt.” Władysław lived in the same suburb the rest of his life.

_______________

The post-war Polish community in Wellington was a strong one. After struggling with a second language during workdays, Poles enjoyed meeting other Poles, chatting in their native tongue and joining in the social activities.

In 2003, 50 years after their marriage, Anna Piotrkowska (née Zatorska), was asked to recollect her time in New Zealand and wrote of one of the Polish dances:

“It was there that I met a very nice young man, Władysław Piotrkowski.”

Anna did not know then that the “very nice young man” was determined to marry someone Polish who would understand his nationality, culture and religion.

At the time Anna lived 165 kilometres north, in Marton, and would not have attended that particular dance had it not been her turn to visit her brother—also Władysław—in Wellington Hospital and she happened to be staying with Zofia Piotrkowska, who had worked with Anna’s mother, Waleria, at the Pahiatua Polish Children’s Camp.

The mothers met again by chance near the hospital. Zofia lived nearby and offered Waleria and Anna accommodation when they were in Wellington. After meeting Anna, Władysław made sure he visited his mother at times that coincided with her visits to her brother.

“I met quite a few Polish girls but we had differences in our thinking, or talking: something that wasn’t quite right. Then I met [Anna] and, well, that was it—and she was young enough to agree with me!”

Władysław and Anna after their wedding at the St Francis Xavier Catholic Church in Marton, in January 1953. The bridesmaids are Anna’s step-sister, Helena Characzko and Maria Piotrkowska.

Anna was 18 and he 29 when they married in January 1953 and Anna proved well-able to cope with her older husband. They had two children, Basia and Bogdan, and have three grandsons and two great-grandsons.

A studio photograph of the family taken in 1965 when Basia was seven and Bogdan 18 months.18

Life had its ups and downs. The joy and support of family helped temper Bogdan’s death from cancer in 2013.

__________

Władysław never fully understood why his father and brother left the rest of the family in 1939. He believed it stemmed from his father wanting to fight for Poland in Poland, and needing to trust his family would survive without him.

Both Jan and Jerzy Piotrkowski survived the war. Jan fought in northern Poland’s Elbląg area and died in Poland in April 1953. Jerzy, aged 14 in 1939, stayed in Warsaw and served with the Polish Home Army (Armia Krajowa, or AK). He did what so many other young people did for the Polish resistance there—relayed messages and information between units in different parts of the city.

Jerzy was seriously wounded during the Warsaw Uprising and had a substantial amount of “metal” inserted in his leg. He visited New Zealand with his wife in 1983, the year Władysław retired, and helped Bogdan build his first house. Once Poland was free from communist rule, Jerzy became a Chief of Police in Warsaw. He died in 1997.

In November 2014, Władysław, with two other Polish veterans of Monte Cassino, Władysław Błażków and Tadeusz Knap, received the Polish Pro Patria medal and accompanying crystal statuette of an encased Polish Orzeł Biały (White Eagle).

The award, established in 2011, honours “Outstanding contributions in perpetuating the memory of the people and deeds in the struggle for Polish independence during World War II.” The Polish Minister for the Office of War Veterans and Victims of Oppression, Jan Stanisław Ciechanowski, presented the awards at the Polish Embassy in Wellington.

Looking back on his life, Władysław had no regrets.

“After the war we had three choices: stay in England, go to Poland to join my father and brother, or come to New Zealand to my mother and Maria. Zbyszek and I decided on New Zealand. It was a good choice. I am happy here.”

© Barbara Scrivens, 2015

Updated May 2019

BLACK AND WHITE PHOTOGRAPHS IN THIS STORY NOT SPECIFICALLY ACKNOWLEDGED ARE FROM THE PIOTRKOWSKI PERSONAL COLLECTION.

EFFORTS CONTINUE TO BE MADE TO CONTACT THE AUTHORS OF THE 3RD CARPATHIAN DIVISION’S PHOTOGRAPHIC COLLECTION AND THE FORMER CHRISTOPHER BEDE STUDIO.

THANKS TO THE NORTH AUCKLAND RESEARCH CENTRE IN THE TAKAPUNA LIBRARY FOR THE LOAN OF AUDIO RECORDING EQUIPMENT.

ENDNOTES:

- 1 - These numbers from:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Monte_Cassino. - 2 - Album Fotograficzny 3D.S.K. W Italii, cz 11, Sierpien 1945, Monte Cassino 27-IV-1944–23-V-1944, Hill 593—one of the most important battle-fields in the Monte Cassino area, first book, photograph no. 72, page 65.

- 3 - Ibid 3D.S.K. W Italii, Monte Cassino seen from hill 593 & 569, first book, photograph no. 86, page 76.

- 4 - Ibid 3D.S.K. W Italii, Dug outs of the Polish Lancers. San D’Onofrio, first book, photograph no. 45, page 44. The same caption has two other spellings: San D’Onufrio (Polish) and Sant’ Oonfrio (Italian).

- 5 - Anders, Lt-General W, CB, An Army in Exile, originally published in 1949. Reprinted by The Battery Press Allied Forces Series, Nashville, ISBN: 0-89839-043-5, pages 178 & 179.

- 6 - Ibid 3D.S.K. W Italii, Victory! Polish flag is flying on the Monastery, first book, photograph no. 78, page 71.

- 7 - The story was published on 19 May 1969.

The president of the SPK in New Zealand, Marian Ceregra, presented Polish president Andrzej Duda with the pennant during the latter's visit to New Zealand in August 2018.

After restoration, the pennant is likely to be displayed at the Belvedere Palace in Warsaw. - 8 - Ibid 3D.S.K. W Italii, 4.2 inch mortars at Casa Maroteschi, second book, Nad Adriatykiem 12 VI 1944–6 IX 1944, photograph no. 25, page 16.

- 9 - Narodnyy Komissariat Vnutrennikh Del, or The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs, the agency that oversaw Stalin’s prisons and forced-labour facilities.

- 10 - The date of the Polish-Soviet Agreement signed in London by Polish Prime Minister Władysław Sikorski and Soviet Ambassador to the United Kingdom, Ivan Maisky, also known as the Sikorski-Maisky agreement. It contained an “amnesty” granted by the Soviet government to “all Polish citizens now detained on Soviet territory…” For more, see the Military Timeline.

- 11 - In this and other stories, I use the single apostrophes to show that the ‘amnesty’ was a

farce:

An amnesty is defined as an official pardon for those who have committed political offences, but the Poles taken by Stalin’s Secret Police, the NKVD, from Russian-occupied eastern Poland in 1940 and 1941 did nothing to deserve their abduction to the USSR. Hitler’s invasion of Russia was what forced Stalin to turn to the West for help. - 12 - From 25 March to 4 April 1942, nearly 44,000 Poles arrived by various shipping vessels from Krasnovodsk on the

eastern Caspian Sea, to Pahlevi in then-Persia.

From 10 August to 1 September 1942, the Polish army evacuated nearly 70,000 more Poles in the same way. - 13 - Probably from the children's poem Stefek Burczymucha.

- 14 - Ibid Anders, page 287.

- 15 - The following five direct quotes extracts from the House of Commons from Vol 420 cc1875-821875: http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/commons/1946/mar/20/polish-armed-forces-government-policy#column_1875.

- 16 - The original wording can be found at:

http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/Geo6/10-11/19/enacted. - 17 - For more about the various Polish Resettlement Camps in the UK, see:

http://www.polishresettlementcampsintheuk.co.uk/ - 18 - Christopher Bede Studios Ltd.