Jackson’s Bay – 150 Years On

Jackson Bay put on a pageant for its sesquicentennial last weekend. The sea sparkled. The sandflies hid. The wind behaved.

Anyone who arrived, however, had to drive around the substantial heaps of debris that slipped down the mountain just a few weeks earlier: a reminder that this beautiful spot should never be underestimated.

Descendants joined friends, guests, and visitors who happened to be there at the time, to commemorate the day that the area’s first settlers waded, were rowed, or were carried ashore on 19 January 1875—a year when 3,000 mm of rain fell on 186 days. The 24 men, 14 women, and 49 children of unknown ages, came from Scotland, Sweden, Ireland, England, Denmark, Canada and Germany. No road then, and no jetty, which was only built in 1939. Schooners waited in the bay while dinghies offloaded people and their possessions.

During the rest of that year and until July 1876, another 109 men, 50 women, and 116 children from the same countries, as well as Poland, Norway and Italy, waded through probably chillier seas. Still others—such as the Polish families of Francizek Kurowski and Robert Lipinski—arrived later in 1876, enticed by the glowing promises that the colonial government advertised.

They were divided into groups along the 20-mile length of what was officially named the Jackson’s Bay Special Settlement. The first mostly English-speakers were offered the only 10-acre sections south of the Arawhata River, on the left-hand side of the photograph below. The rest of the sections were mostly 50-acres. Scandinavians were sent farther north to the Waiatoto River. Italians—who dreamt of growing grapes and vegetables—went even farther north to the swampy plains of the Okuru River. Most of the Poles were offered sections directly inland and south of the Jackson’s Bay beach, along the banks of the Smoothwater River that runs along the narrow valley between the Stafford Range and Burmeister Tops.

It did not take long for dreams to fall apart for settlers like the Poles, who had fled Prussian persecution and arrived with few possessions and little money.

The deal at Jackson’s Bay (150 years ago, its name had a possessive) was that settlers were guaranteed paid work for three days a week at eight shillings a day, and were expected to use the rest of the week to clear and improve their sections. But the work did not materialise, and high prices at the government-sanctioned general store meant 24 shillings a week was not enough to keep a family fed and clothed.

The Poles knew how to work land—they had been mostly farming serfs—but they soon found out that they could not grow even the most basic of vegetables on their bush-clad and flood-prone sections in the extremes of weather.

South Westland could not have been more different from the wide, fertile plains of northwest Poland, land they would not have left had it not been for their lives becoming more and more squeezed under Prussian rule. (Poland had been partitioned by its three empire neighbours for the first time in 1772, and 100 years later in its Prussian-partition, Polish schools had been banned, as had the language, any written work, the Polish spelling of their names, and even Catholicism, the faith of most Poles. Even worse, all Polish men were automatically conscripted into their oppressor’s strict 20-year conscription system.)

Today, a Department of Conservation sign and a marker show the steep beginnings of the track to Smoothwater.

When any of the settlers tried to supplement their incomes by taking jobs elsewhere, the resident agent Duncan Macfarlane—a former merchant from Hokitika—punished them by excluding them from local contracts. Thanks to his signature apparently needed on any salary cheque, he controlled all the settlers’ salaries, no matter where they worked. He ran the store through a system that guaranteed indebtedness. At the time of the 1879 Commission of Inquiry into the complains against the settlement, 58 of its families owed nearly £4,000.

The Poles had all left, destitute, by 1879. For the Poles and Italians, the inability to speak English had not helped.

The only thing that all the settlers agreed on was that they needed a jetty, estimated to cost £1,500. Without that piece of infrastructure, and with a fickle sea, getting goods to and from Jackson’s Bay was unreliable. Even if there had been a regular market for fish, for instance, produce from the bay was likely to be spoiled before it got to market. The same went for fresh goods arriving: the commission heard several complaints about rotten seed potatoes arriving at Jackson’s Bay.

Macfarlane seemed to get a ministerial go-ahead for a jetty in 1878, and even started the build, but it was thwarted. By the time it was finally built in 1939, a regular air service to Haast and Okuru had been running for eight years.

Visitors to Jackson Bay these days arrive by road. My husband and I travelled via Hokitika, where several of the Polish Jackson’s Bay families later moved. Our waitress at the Station Inn was surprised that there were any Poles among the settlers. She had lived on the coast for 40 years and had never heard of any, which prompted my counting: of the 362 people who arrived in Jackson’s Bay between 1875 and 1876, 130 were Poles. By the time the last Polish family left in 1879, 15 babies had been born and one—Joseph Gorowski—died at six weeks in April 1878. In June 1877, a tree that fell on their house in Smoothwater crushed mother-of-three Rosalia Wicki, and a year later, Franciszek Kurowski perished in a boating accident and left his pregnant widow with four children.

_______________

Jackson Bay is where South Westland’s coast road ends. Apart from the area immediately adjacent to the beach, none of the “town” of Arawata on the ambitious 1875 map below was ever built. The Esplanade today veers left on what was Pier Street and peters out. Not that anyone needs a street address in Jackson Bay. Directions do nicely.

Organiser of the sesquicentennial, Kathryn Bennie—who bought a bach on Pier Street with her late husband, Ewan, 14 years ago—suggested we walk across the valley to the other side. It is the High Street on the map below and runs along the dip between the hills in the photograph above.

Jackson Bay’s planned High Street in 1875 is now the Wharekai Te Kou walk to Ocean Beach, below.

On a sunny day it is difficult to imagine a rainfall of more than 3,000 mm. There is little sign of the landslip of December 1886—dislodged from the mountain behind after four days of torrential rain—which covered the hotel and washed away the owner’s 13-year-old son, Charles Robinson. If there were more roads in the town, they are now hidden by the fauna now growing over the slip.

Kathryn: “The wairua of the place instantly took hold of me and I was compelled to find out who the people were who are buried in the cemetery. It bothered me that there were no proper records anywhere. I delved in. Little did I know it would take me on such an incredible journey that would keep exploding at every turn. During that process I automatically ended up with files on the families.”

Kathryn’s research has led to a permanent information board in the DoC kiosk opposite the Craypot that lists all the families of the 1875–1879 settlers.

She and other volunteers have also cleared away slips from Arawhata cemetery, and uncovered graves of those interred there. Few have names or headstones, and many are marked by moss-covered rocks that could have been easily overlooked last weekend had it not been for volunteers placing hydrangea flowers on each one. Below are the three Heveldt graves.

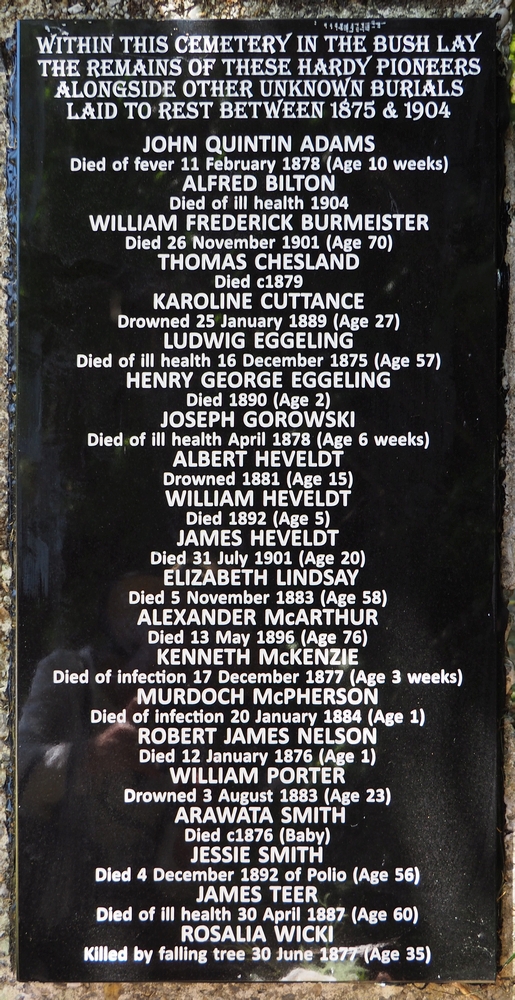

Kathryn knows there are others hidden elsewhere in the bush, but those whose names she has been able to verify now have a permanent plaque, unveiled on 18 January 2025 at the entrance of the cemetery.

Thanks to Kathryn, the “UNKNOWN Polish settler’s wife…” now has a name.

Above, Kathryn Bennie with Polish historians Ray Watembach, left, and Paul Klemick, at the Jackson Bay sesquicentennial celebration dinner. Ray is in traditional Kaszubian costume, and Paul in Kociewian, the two districts in Poland from where the Poles who arrived in Jackson Bay originated.

—Barbara Scrivens

27 January 2025

_______________

If you would like to comment on this post, or any other story, please email editor@polishhistorynewzealand.org/

For more about the Jackson’s Bay Special Settlement, go to https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/jacksons-bay/

For more photographs of the sesquicentennial, see https://www.facebook.com/jacksonbay150/