Dropping Bread; Planting Trees

Memory is one thing, knowledge another. In times of political upheaval, young children left orphaned are most at risk of losing their identities. What two- or three-year-old would know his surname, or even the concept of his mother and father having names other than “mummy” and “daddy”?

Kazimierz Zając, the subject of one of our latest stories, had only vague memories of his mother, a farm in eastern Poland, a railway station, and being taken to a place far, far away. When he arrived in New Zealand in 1944, aged six, the only facts known about him were his and his mother’s names, “facts” he could not be sure were correct—they came from people who had met his mother before she died, and given to the first orphanage that looked after him in southern USSR.

In theory, Kazik stood no chance of ever finding out his background: the facts given to the first orphanage were correct, but they were muddied after he arrived in New Zealand. Officials here fabricated his mother’s maiden name and his father’s first name. Kazik knew his real birthdate was unlikely to match his official one—the same day he stood in the Pahiatua administration office when someone asked him his birthdate, and he said he did not know.

When someone from the Pahiatua camp knew I planned to interview Kazik, they said I “wouldn’t get much” from him. They were wrong. Kazik’s story, on our War Immigrants page, shows how truth eventually squeezes through convenient plastering.

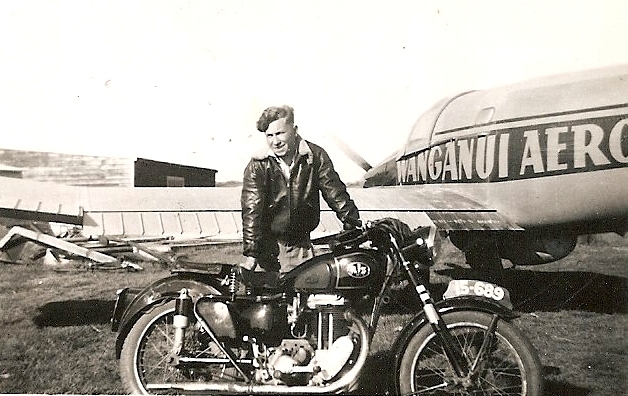

He was lucky. On the other side of the world, his mother’s family refused to dismiss the notion that he was alive somewhere, and kept looking for him. Even if they had not found him, his Irish foster family in New Zealand embraced him and his dreams of flying. Aged eight he declared he wanted to drop bread over Poland: he had heard of the country’s post-war poverty.

Kazik’s experience as a Polish civilian caught in WW2 was completely different from that of Ronald Lipinski, two years older, who spent the war in rural New Zealand. Born in Carterton, Ronald descended from Poles who immigrated to New Zealand in 1876. Although he did not have the indignity, like Kazik, of having to carry a post-WW2 Alien Registration card, he did experience prejudice against his Polish surname.

Aged 15, Ronald moved to Tauranga with his family, and loved the opportunity his seaside school gave him to participate in water sports; rowing his favourite. He became a surveyor. Once too busy to spend enough time training for rowing competitions, he stayed connected to the sport by sharing his knowledge through coaching—and met his future wife, Roselyn.

Ronald absorbed the work ethics of his father and grandfather, and followed their modelling. The extent of his dedication to his community became evident to me only after he died in April this year, and Roselyn gave me his CV. Apart from his uncanny memory for names, what most impressed me was his personal instigation of a project involving the planting of 157,000 seedling trees on Old Baldy, a landmark hill south of Tauranga, known in Maori as Kopukairoa. His story is on our Early Settlers page.

After retirement, Kazik and Ronald both delved into their family histories and discovered unexpected aspects. I could tell you more, but that would spoil the surprise of the reads.

—Barbara Scrivens

28 June 2019

_______________

Kazik Zając’s story can be found at: https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/kazimierz-kazik-zajac/

Ronald Lipinski’s story can be found at: https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/ronald-george-lipinski/

_______________

If you would like to comment on this post, or any other story, please email editor@polishhistorynewzealand.org/