A Fuller Picture

The Cartvale passenger manifest for its 1874 voyage from London to Wellington presented itself as so normal and straight-forward.

The 1,250-ton iron ship built in 1872 carried predominantly English passengers, and four Polish families, and I wrongly assumed that they had an easier voyage to New Zealand than Poles who sailed directly from Hamburg.

The Cartvale manifest for the 418 “souls” aboard seemed meticulous. The double pages on one side gave passenger’s names, ages, places of origin, occupations, and how much their passage was costing the new colonial government. The other side showed further accounting. Apart from a few notations regarding payments or promissory notes, the “remarks” column remained empty.

Its summary—on pages pre-printed with the headings “Summary”—revealed that most of the men were general or farm labourers, most of the single women were servants, and others brought with them skills such as carpentry, blacksmithing, and shoe making. An additional summary on the final page divided the “souls” into nationality and gender. Nothing outwardly unusual in a vessel carrying new immigrants to a colony needing labourers and servants. Nothing to suggest that this was the first time the ship’s captain and surgeon-superintendent had been involved in transporting people. And no hint of the deaths of 19 of its youngest passengers by the time it sailed into Wellington harbour on 11 October 1874.

Three missing pages—six sides—neatly sliced from the promissory notes section may have sanitised the real story of the voyage, which I did not investigate until a descendant of one of the Polish families sent me a separate certificate of births and deaths that occurred during the ship’s 108-day journey, and its subsequent quarantine at Matiu/ Somes Island, where four more infants died. That led to my taking a deeper look into the digitised letters and reports on the Cartvale held by the National Library of New Zealand.

Queen Victoria’s British Empire prided itself on its shipping fleet, and this was a time of mass migration from Europe. Immigration officials in Wellington (then known as Port Nicholson) would have expected such a new ship to have been fitted to cope with its human cargo, but when they boarded to investigate why there had been so much sickness and so many deaths among the children, they instantly found the reason. Immigration commissioner, Dr Alexander Johnston, did not sanitise his words. His report described “various” cramped compartments in the so-called ’tween-decks as “teeming with filth” and accumulated “foetid matter.”

In the second sentence of his report, Dr Johnston blamed the state of the ship’s living quarters “in some measure to the inexperience on the part of the surgeon and captain.”

The slope of the decks carried “filth” from the single men’s quarters in the “fore hatch” into a “waterway in the ’tween-decks, which formed a receptacle for all the filth of the passengers, without allowing it to go overboard.”

Even if there had been a way to divert the sewage from the family quarters, the ship-fitters for the New Zealand Shipping Company had packed the immigrants’ bunks so tightly that there was no access. Surgeon superintendent, Robert Robinson, having completed his first voyage in charge of the health of large numbers of immigrants, complained to the immigration officials that he had “often to leave his surgery owing to the effluvium from these places.” He did not seem to consider it his business to investigate the reason for the stench, or solve the problem, much less wonder what it must have felt like to be trapped in a ship under those conditions for so long.

There was enough slop about on 6 August 1874 for one of the single women to “throw pigs muck” into the face of one of the constables who had apparently made himself obnoxious.

Passenger George Smith, a shoemaker from Suffolk, wrote in his diary that on 24 June 1874, the day the ship left the London docks to overnight at Gravesend, a family with a child with whooping cough had been “sent on shore.” The next day, another family “with measles” was ordered to disembark.

On 14 July, two-year-old Alfred Burgess became the first child to die aboard the Cartvale, of croup, which claimed eight others. Measles, whooping cough, and a miserable collection of infections contributed to other deaths. Seventeen-month-old Albert Borkowski died of measles on 9 October 1874, the last of 19 babies and children younger than five who died on the voyage. Ship’s surgeon Robinson recorded another four who died in quarantine up to 17 October 1874, but not Albert’s brother, Stanisław. He died, aged four, on 20 October 1874.

Robinson blamed the deaths of three of the children on their Polish and Danish parents, whom he described as “foreigners” prejudiced against his treatment: “In one case the child was not brought to my notice until a few hours of his death, and in the other two cases all treatment was steadily refused.”

In his report, Robinson also attributed the children’s suffering to their “markedly poorly-nourished” states, not ready for the “change of diet and altered mode of life” (that he considered “a serious undertaking even for adults”), and their lack of warm clothing during the rounding of the Cape.

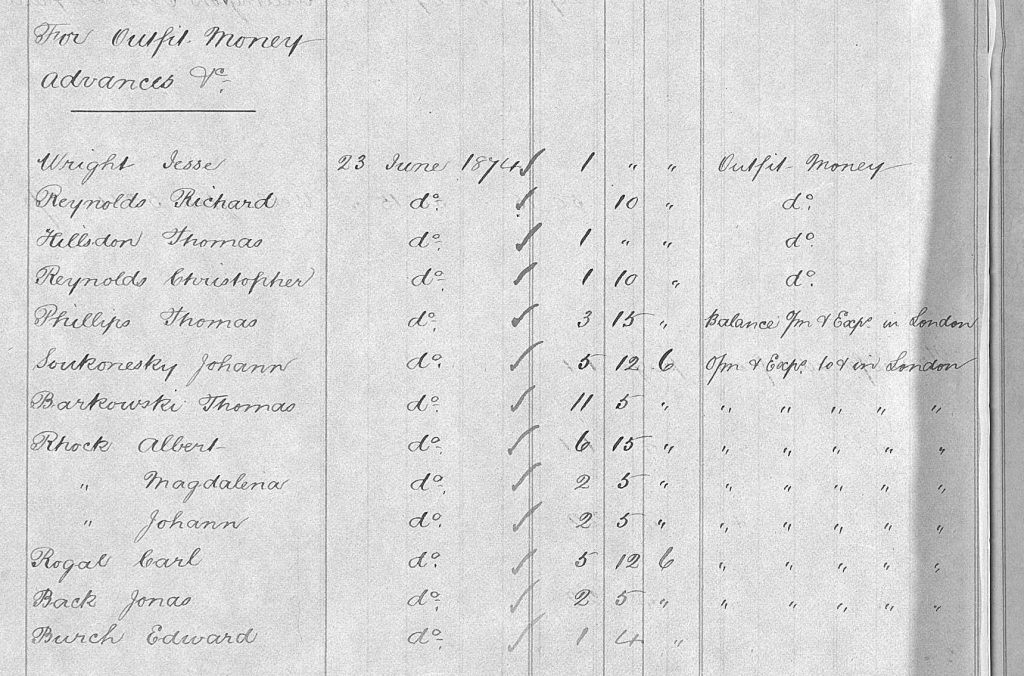

Robinson’s lack of empathy for the “foreigners” may be attributed to the obvious language barrier, and his ignorance regarding where they came from, and what they had sacrificed to get to the ship. In 1874, ports in Britain made a bustling trade from the millions of continental Europeans migrating mainly to the Americas. The four Polish families were fleeing ethnic and religious persecution in Prussian-partitioned Poland. They caught ships bound for the USA, and disembarked at the ports of Hull and Leith, north of Edinburgh. If it had not been for the remaining half of page 27 of the ship’s manifest escaping the cut, one might have speculated that the Borkowski, Roda, Rogal, and Suchomski families—11 statutory adults, and nine children 10 years and younger—took unnecessary risks by perhaps abandoning an original plan to go to America. But that page 27 shows the significant amounts they signed in promissory notes unrelated to the actual cost of the voyage.

Under a heading “For Outfit Money Advances Etc,” the Poles made up at least six of the 13 entries, and owed by far the most. Thomas Borkowski, with a wife and five children, owed £11 5s, which included expenses “to & in London.” The Rhock (Roda) family, with four adults and three children, owed the same. Carl Rogal, with a wife and whose 17-month-old son, Józef, was the second child to die, owed £5 12s 6d, the same as Jan Soukonesky (Suchomski), with a wife and a three-year-old son who survived the voyage. Five others on the list owed £1 to £1 10s for outfit money alone, which suggests that the Poles paid a high price to travel to London from Hull and Leith.

Warm clothes? What was the so-called outfit money for? Surely it would have been provided if it had been paid for?

Change of diet? Even before the immigration officials wrote their report on the insalubrious conditions aboard the Cartvale, they pushed for changes to the “dietary scale” of babies and children carried to New Zealand on future voyages. They directly attributed the ship’s grossly inadequate “dietary scale” to the high mortality rate among the youngest passengers. Their words “absolutely necessary,” “adopted immediately,” and “instructions in this respect positively imperative” despite probable “additional expense” could not have been clearer.

Subsequent voyages provided mothers with babies younger than a year with milk and special food. Children up to 12 were to receive daily portions of “preserved” instead of “salt” meat, a pint of milk, and three pints of water. Every other day they were to receive eight ounces of oatmeal and four ounces of preserved soup, and weekly rations of flour, rice, and sugar.

Perhaps more significant was the edict that each person ill in a ship’s hospital was to receive an additional daily quart of water.

Altered mode of life? The Cartvale families must have been shocked at the conditions ’tween-decks, but no one can know what kinds of lives they left behind to start new ones in New Zealand. Life aboard ship was different for immigrants sailing from England after the Cartvale, remembered again by Dr Johnston in his report on the Soukar, which arrived on 2 December 1974:

“The immigrants were located in the usual manner; all having their berths in blocks, with alley-ways right round. These alley-ways were a great convenience, as they enabled the waterway which was in the ’tween-decks (as in the Cartvale) to be kept clean and sweet, and prevented berths being placed right over it, as in that ship.”

Twenty-four babies, infants, and young children, and their families, paid for that lesson.

—Barbara Scrivens

31 October 2020

_______________

The immigration officials’ reports can be found in the Appendices to the Journals of the House of Representatives (AJHR), 1875, Session 1, IMMIGRATION TO NEW ZEALAND (LETTERS TO THE AGENT-GENERAL, TRANSMITTING REPORTS UPON IMMIGRANT SHIPS), D-3, pages 30 & 35. Also, IMMIGRATION TO NEW ZEALAND. LETTERS TO THE AGENT-GENERAL, D-1, pages 11–13.

_______________

George Smith’s diary is held at the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, reference: MS Papers 309 George Smith Diary.

_______________

More on the four Cartvale families in the story Marshland: The Place Where Flax Grows Profusely, via the link: https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/marshland/

If you would like to comment on this post, or any other story, please email editor@polishhistorynewzealand.org.