Refugee Status

Today, 75 years ago, the Carnarvon Castle docked at Southampton carrying 1,173 Polish refugees. Aboard were both my widowed grandmothers, my mother, and four uncles.

The 1,173 had embarked in Durban and Mombasa, and had been among more than 21,000 mainly women and children who had spent more than five years in Polish refugee camps in southern and eastern Africa. They had escaped the forced-labour facilities of the USSR in 1942 with their husbands, uncles, and siblings who had enlisted in a Polish army formed there. While their menfolk fought in European conflicts, the Allied military authorities sent them to Africa.

I know the date—28 June 1948—but would not have remembered the anniversary had I not received an email from the National Archives in London last Friday telling me that it was Windrush Day, marking 75 years since the arrival to the UK of the Empire Windrush from the Caribbean. I waited for news of a Carnarvon Day, but it did not materialise.

I found the Carnarvon Castle passenger list in 2010 thanks to a website about the 265 Polish Resettlement Camps established in Britain from 1946 in former British, American, and Canadian army and air force barracks. The website had a list of ships carrying Polish refugees. My mother, Kazimiera Surowiec, had told me they arrived from Africa in 1948. I went through each ship’s passenger list until I found my Surowiec and Nieścior family members, coincidentally, on the same ship.

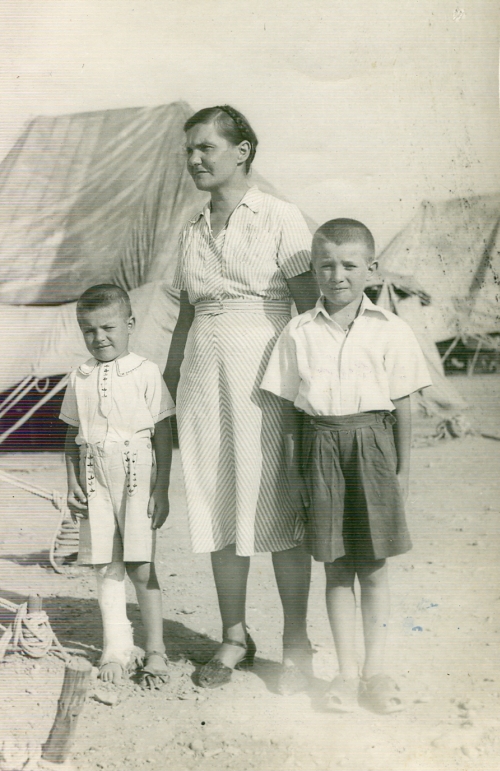

I wondered whether my grandmothers had met on the ship, or whether my uncles had played with one another. The latter scenario was more probable, because boys play, and my uncles were then aged 11, 12, 13, and 15, but it was more likely that groups that had been together for the past five years, remained together on the ship.

The Windrush also carried Polish refugees—66 who had been living in a Polish refugee camp in Mexico, and who joined the ship in Tampico—but besides the Windrush Poles, the make-up of the passengers on the two ships was very different. The Carnarvon Castle carried 470 children and teenagers, while most of the 1,027 Windrush passengers were former service personnel who embarked in Trinidad, Kingston, Havana, and Bermuda. Of the 84 men aboard the Carnarvon Castle only two had military backgrounds: a 66-year-old Colonel Feliks Dziewicki, who boarded in Durban with his wife, and a 53-year-old Feliks Burlinski, who gave his occupation as “military” and apparently travelled alone from Mombasa.

On the Carnarvon Castle, single mothers headed 238 of the families aboard—71 percent. Single fathers headed just seven families. The ages of the 53 fathers who arrived with their wives and children ranged from 48 to 73. The dearth of men, and their ages, reflected the fact that during their escape from the USSR, any Polish man who could, joined the Polish army.

The Carnarvon Castle passenger list shows 24 sets of parentless siblings: 14 of those brothers and sisters had just one sibling, eight had two, and two groups shared three siblings. Six families were three-generational, and the note that 72-year-old Maria Stano “did not sail” next to the date 4 June 1948, suggests that this was when passengers embarked at Mombasa.

My mother, and my uncle Stanisław Surowiec were the last two people recorded as embarking in Durban. It is unclear why they were listed after the Z-surnames, and separated from their mother and younger brother, but the same thing happened with three others in Mombasa. The Durban passengers were the first listed, so I assume that the mail ship sailed from the UK around the Cape of Good Hope, up the African east coast, and through the Suez Canal.

In 2010, I counted 374 women older than 35, and made a note that I did so because babcia Surowiec was then 40, and babcia Stefania Nieścior, 43. There were 243 girls and young women younger than 20. The fewer teenaged boys and young men would have been thanks to the Polish army taking on the care and education of teenaged mainly boys in the Middle East from 1942. My father, aged 20 in 1948, had joined the so-called junaki, and had arrived with them in Britain the year before.

Of the 84 men, five were aged 48 and 49; 35 were in their 50s; 33 were in their 60s; 10 were in their 70s, and the oldest was 82-year-old farmer Michał Naronowicz, who travelled alone. The oldest woman, Julia Wajs, was also 82, but she had a 40-year-old daughter-in-law and four grandchildren as company.

By far the most common “occupation” on the passenger list was that of student: 475. They were followed by 289 ‘housewives,’ 113 dressmakers, 65 farmers, 23 teachers, 22 nurses, and 13 ‘clerks.’

According to the National Archives, the Windrush passengers had been “invited to help rebuild Britain after World War II.” Thousands of Caribbean men and women had been recruited by the British government during the war, and the British government had been “encouraging migration to boost the workforce.”

In contrast, the British government encouraged Poles displaced during WW2 to return “home” to help rebuild their own country. The Poles who refused to return must have been an embarrassment for that British government, which had, with the USA, allowed Stalin to re-draw the eastern boundary between Poland and the USSR, and had accepted the Moscow-controlled post-war Polish puppet regime.

Some of the Polish military personnel who refused to return to post-war Poland joined their families in New Zealand, but for those who were like my family in Africa, all they could do was wait for others to decide their fates. The Poles there had lost their land in eastern Poland, so in any case, there was no “home” to return to. My mother told me how, during that sea journey from Africa to England, she and her brothers had begged their mother to return to Poland. Babcia, widowed mother of three teenagers, refused.

Seventy-five years on, the word “refugee” is still an awkward one. A refugee is generally understood to be someone who flees, or is forced to leave their homeland for any variety of reasons—war, persecution, a natural disaster. And some of the Poles in the beginning of WW2, did escape a Poland being overrun by Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia. But in 1940 and 1941, Stalin’s secret police, the NKVD, kidnapped the Poles in the refugee camps in Africa—and those who arrived in New Zealand in 1944—at gunpoint, removed them from their own homes, and took them to forced-labour facilities throughout the USSR.

In New Zealand the term is sometimes glossed over, and exchanged by some Polish refugees for “invited,” but I believe that diminishes the epic journeys that they made to get themselves out of the USSR by any means available, be it by rail, raft, or foot.

I know that the four to eight percent of Poles who did escape the USSR in 1942 and 1943 were the lucky ones, but they were strong too, in many ways, and I am proud to call myself the daughter of refugees who were not invited anywhere.

—Basia Scrivens

28 June 2023

_______________

The Polish Resettlement Camps in the UK website: https://www.polishresettlementcampsintheuk.co.uk/PRC/PRC.htm

_______________

For more on life in the Polish refugee camps in Africa, see the stories of the independent journeys that Joanna Adamek Kalinowska, Joe Gratkowski, and Wisia Sobierajska Watkins made to New Zealand:

Joanna Adamek Kalinowska: https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/joanna-adamek-kalinowska/

Joe Gratkowski: https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/joe-gratkowski/

Wisia Sobierajska Watkins: https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/wisia-sobierajska-watkins/

_______________

If you would like to comment on this post, or any other story, please email editor@polishhistorynewzealand.org/