The Beekeeper Soldier

The last issue of the Pszczelarz (Beekeeper) appeared in Poland in August 1939.

The National Library of Poland in Warsaw keeps one. I cannot describe what it felt to handle it, gently turn its pages, and know that I was reading the same words, and looking at the same photographs that my paternal grandfather would have seen and read. It was smaller than an A4 page, the cover a dull red-cerise.

My interest in the publication was purely because I had found out that my grandfather, Stanisław Nieścior, wrote at least one article for the monthly magazine. I arranged to view that publication, and others, and ordered copies of relevant pages—photography was not allowed. I did not check the CD that the copying librarian gave me until I was back in New Zealand: it held all the pages I had asked for except the one with my grandfather’s article, which I remember as a complaint about a neighbour’s sloppy beekeeping.

News about the sham referendum in eastern Ukraine late last month immediately made me think of that grandfather, who survived the 1919–1920 Polish-Soviet War, and WW2, but who died in Italy in 1946 knowing that his farm in eastern Poland had been ceded by the Allies to Stalin’s communist USSR—the same Allies who Poland had fought beside for so long.

My grandfather and his family were among the hundreds of thousands of Polish civilians that Stalin’s soldiers captured in 1940 and took to the USSR to work as forced-labourers. Most of those who escaped the USSR, did so in 1942 through a Polish army formed on Russian soil. Anyone who could, joined that Polish army, including that grandfather, then aged 45.

Within the relative safety of the Middle East, the Second Polish Corps asked its soldiers to write depositions and fill out questionnaires about their arrests by the Soviets, the conditions in the USSR forced-labour facilities, and the date and circumstances of their release. General Władysław Anders, Commander-in-Chief of the Second Polish Corps, apparently wanted as many of his soldiers to give testimony as was possible.

Some soldiers vented screeds, some had their testimonies taken by others, some were suspicious of the request and possible repercussions, and some—like my grandfather—wrote within the given spaces. Their replies are housed at the Hoover Institution on War, Revolution, and Peace at the Stanford University in California.

Family members in Poland described my paternal grandfather as stern. He was obviously not impressed when, on 20 October 1939, the Soviet army arrived in Niweck in the Wołyń province of then-eastern Poland. He wrote his answers in a guarded, passive voice, and I wonder whether it was his way of distancing himself from events:

After the invasion, on the pretext of “saving” the local Ukrainians from the Poles, Soviet decrees led to the repression of the local Polish people, who became subjected to searches and arrest. People considered activists were also arrested.

Then, the Soviet machine started to organise so-called “elections.” Pre-election propaganda proliferated and caused agitation among the locals, who were forced to attend communist-focused assemblies and meetings. From those gatherings, a “census of inhabitants eligible to vote” was created “according to the USSR constitution of voting.”

Communist activists from the Russian population were “elected” onto to an election commission by a so-called Assembly of West Ukraine and West Belorussia, which also selected the candidates.

The elections, held in Niweck in November 1939, were compulsory. Sick people were transported in carts. The results were no surprise.

The elections were followed by the “dismantling” of Polish farms.

Polish civilians soon felt the decisions of those new in power. More than 1.5-million were captured in their homes, at gunpoint, bundled into cattle trains, and sent to hundreds of forced-labour facilities scattered throughout the USSR. Like in all wars, the civilians bore the brunt of the suffering: General Anders estimated that at least half the Poles taken by the Soviets in 1940 and 1941, were dead by the time the Polish army managed to get just 115,000 out.

I am not sure what was worse: My maternal grandfather dying in action in northern France, aged just 34 in 1944, but not knowing of the Allies’ perfidy, or my paternal grandfather surviving Monte Cassino to find out that the land he worked so hard on had been given away, and that the freedom he had helped fight for in two conflicts involving Polish territory was for naught.

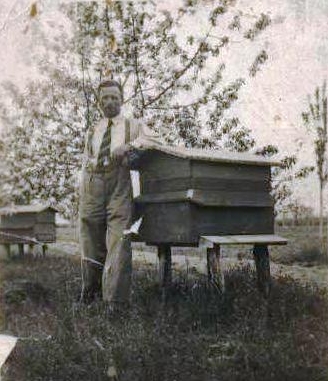

Stanisław Nieścior also contributed to the Żołnierz (Soldier). He wrote about horticultural husbandry, and had a special interest in grafting fruit trees. I like to think that the photograph below of him was taken in his grafting nursery, and that the dark shapes on either side of this path are juvenile trees. I also like to think they survived his absence, but I doubt it.

—Basia Scrivens

30 October 2022

_______________

For more information about the post-war Polish immigrants to New Zealand, go to https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/war-immigrants/

If you would like to comment on this post, or any other story, please email editor@polishhistorynewzealand.org/