The Untold Stories Project

I remember as clearly as yesterday, the first time I stood in a school playground. The ground was grey, there were a few dark trees in the background, and the children running around were shouting things I could not understand. I looked elsewhere, but the babble did not change. I had been thrown into a strange, confusing pool.

I became a tortoise, comfortable in my shell. My parents did not help me with any homework I may have had; my father worked nights, and my mother had my three younger sisters to deal to, the baby six weeks old when I started school. I learnt to look after myself, developed a good memory, and a stutter.

I know I didn’t philosophise or question why I had to become “one of them” in the playground but I did. I absorbed the English language, loved reading, and my English accent was the same as my peers.

One of the first words I absorbed that was not in a reading book was “foreigner.” At first, I thought people called me that because I was born 30 miles away. It did not occur to me that it was because of my parentage, although at school, I did wish I had an easier surname. My mother called me Basiu, and a child overhearing her decided it was “Bash You.” I knew enough by then to say, “I’ll bash you in a minute!”

In my last year of primary school, I had my hand up an entire sewing class; we had to have our work checked before we could carry on. The next class, when the teacher again ignored me, I got up and followed her along the rows of desks. Finally, she turned around, asked me if I were a sheep, and told me to sit down. When she did look at my hem, she told me I had sewn it right-to-left instead of left-to-right and ordered me to re-do it.

Those memories came back to me as I watched the documentary Untold Stories, about six families with origins in Belarus, Bulgaria, Germany, Greece, Latvia, Lithuania and Romania, who settled in Palmerston North. Most arrived in New Zealand as Displaced Persons, around 1951—10 years before I started school in England. The recollections of their children reflected mine in so many ways.

_______________

Mary Zambazos, the daughter of Konstantinos and Panayota Zambazos (pictured above with her mother and sisters): “The teachers at primary school made us feel different… I still have vivid memories of being told by one of my teachers when I was about seven or eight, ‘I bet you can’t wait to get married and change your name to Andrews.’ As a result, I’ve never changed my name, and I’ve given both my daughters the name Zambazos as a middle name.”

Tania Kopytko, the daughter of Michal Kopytko, has driven the Untold Stories project. Her father ended WW2 with the Polish army, and had been demobbed in England, but he was born in western Belarus. When the Soviets over-ran his country in 1939, the new authority ordered him to inform on a neighbour: Michael’s refusal led to his being sent to a gulag in Siberia.

Michael’s series of escapes from the gulag, the Soviet Army (after forced conscription), German prisoner-of-war and starvation camps, make the title of his section, A Lesson in Survival, a fitting one. He did return to his home village and was recruited by the occupying Germans to be a local village policeman. He was again forced to flee, and joined the Byelorussian partisans operating in the surrounding forests until the 1943 Soviet advance west pushed him and his colleagues the same way. When they were captured in France, their Polish papers convinced their captors that they were not Germans, despite their unfamiliar uniforms. They were given the option of moving to a Displaced Persons camp, or enlisting in the Polish army. Michael Kopytko made the only choice his conscience allowed, and he served with the Second Polish Corps in Italy and Egypt. He met and married Tania’s New Zealand mother in London.

Tania: “I became aware that our family was different from Kiwi families around us at a very young age… while Tania is popular now, it wasn’t then… and I had an unpronounceable and unspellable surname.

“On my mother’s side of the family, there were family members, and my grandmother, who were not happy that my mother had married a foreigner… You sense as a child that not everything is easy and that you’re a bit different.

“There was also Cold War prejudice. I felt that at College Street school. I remember children saying to me, ‘You’re a commie.’ I went home to dad and said, ‘What’s a commie?’ and he got so angry. He always brought me up to be strong.”

Mychelle Mihailof’s Bulgarian father, Zhelio (John), arrived in 1951 off the SS Goya. She tells how the DPs spent six weeks in the Pahiatua refugee camp undergoing intensive language courses:

“The assimilation policy of the 1950s meant that you took on New Zealand culture; you left your culture behind. You became a New Zealander, you took on the British way of life that we had here.

“He would have been happy too, but he found that you can’t give up your culture; you can’t give up what is inherently part of you.”

_______________

Their surname was constantly mispronounced and spelt in different ways, and John Mihailof never lost his strong accent, so he could never have been mistaken for a New Zealander. Mychelle recounted how he bounced between the two societies, not fitting in either, until he visited a communist-free Bulgaria in 1990 and cemented his European heritage:

“To know and embrace your whakapapa is so important. It’s the foundation for your identity, for your sense of self, the connection to the land and to the people that you come from.

“The people they mixed with were loud, colourful, their special occasions were filled with music and dancing and lots of drinking and lots of eating and different languages being spoken.”

_______________

Not all the European DPs in Palmerston North were as gregarious. Bruno Petrenas’s Lithuanian father, Felix, above, was “very quiet and very silent” about parents and six siblings, whom the invading Soviets sent to Siberia in 1939. He never saw them again. Felix escaped the Soviet army in 1945 when he surrendered to the Americans on the Elbe river. When he married Bruno’s German mother, Annielisa, both became Displaced Persons who were not allowed to live in Germany. They were among nearly 1,000 DPs that the Hellenic Prince carried to New Zealand in 1950 on behalf of the International Refugee Organisation.

Lucy and Martins Ozolins were on the same ship. They had had their farm in Latvia requisitioned by invading Germans in 1941, and had lived under constant threat of death if the Germans found out that they fed the slave labourers they were given.

In 1944, when the Ozolins realised that the Germans were retreating and the Soviets were advancing, they fled west. They stopped when they discovered they were in the safety of defeated Germany’s British Zone.

_______________

The Tsaclis family is the sixth and last represented in the documentary. WW2 put a stop to their three-generation merchant shipping business that operated around the Black Sea. A post-war communist Romania nationalised property and businesses, and “life became dangerous.” People disappeared or died and future craftsman joiner John Panayotis Tsaclis, then 18 and under threat of being sent to Siberia, fled Romania with his mother, Getta, to Greece. They arrived in Wellington in May 1951, John pictured here fourth from left.

This website is dedicated to people who, like the six families here, did not shout about their achievements, but simply got on with making new lives in New Zealand, and enriching their communities in the process. Tania Kopytko’s father became a postman who was able to rescue previously ‘undeliverable’ letters with writing unrecognisable to his English-speaking workmates, and got to know the wider DP community in Palmerston North. The tiny church he created from Tania’s converted playhouse attracted European neighbours with various home-languages.

With their large, productive vegetable gardens reminiscent of those left behind, their skills—ranging from joinery and cabinetry to cooking and dressmaking—their charm, strength, and an overwhelming desire to provide better lives for their children, the so-called Displaced Persons of Palmerston North found their own way of fitting in.

WW2 most disrupted the lives of people from invaded countries that were taken over by communism, such as in central and eastern Europe. Their refugees and displaced persons were often not wanted in non-invaded countries like England or New Zealand or North America, which needed them to help build their own post-war economies.

As a child, I was sheltered by a wider, strong Polish community in England, and am not surprised that the same happened here. The pressure to fit in is enormous but the inherent diversity imported through immigrants from different countries is what gave the bland Victoria sponge Englishness of the 1950s and 1960s the spice and vigour it lacked.

The documentary The Untold Stories Project is available through https://youtu.be/ZgbGneFehho.

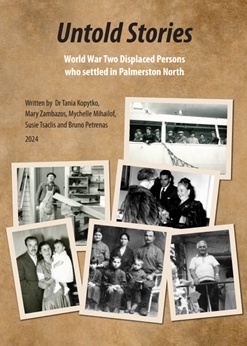

This weekend sees the launch of the book Untold Stories – World War Two Displaced persons who settled in Palmerston North. Written by Dr Tania Kopytko, Mary Zambazos, Mychelle Mihailof, Susie Tsaclis and Bruno Petrenas, it provides details on the journeys of the six families to New Zealand, and their time at the Pahiatua camp, and includes a chapter on research processes and advice.

On Saturday 14 September from 2 to 3.30 pm, Palmerston North Central Library in the Square will host a presentation, discussion, and refreshments for people interested in the story and buying the book for $20.

On Sunday 15 September from 2 to 4 pm, the Untold Stories writers will be at the smaller venue at the Pahiatua and Districts Museum, 33 Sedcole Place, Pahiatua, to chat and answer questions.

—Basia Scrivens

10 August 2024

_______________

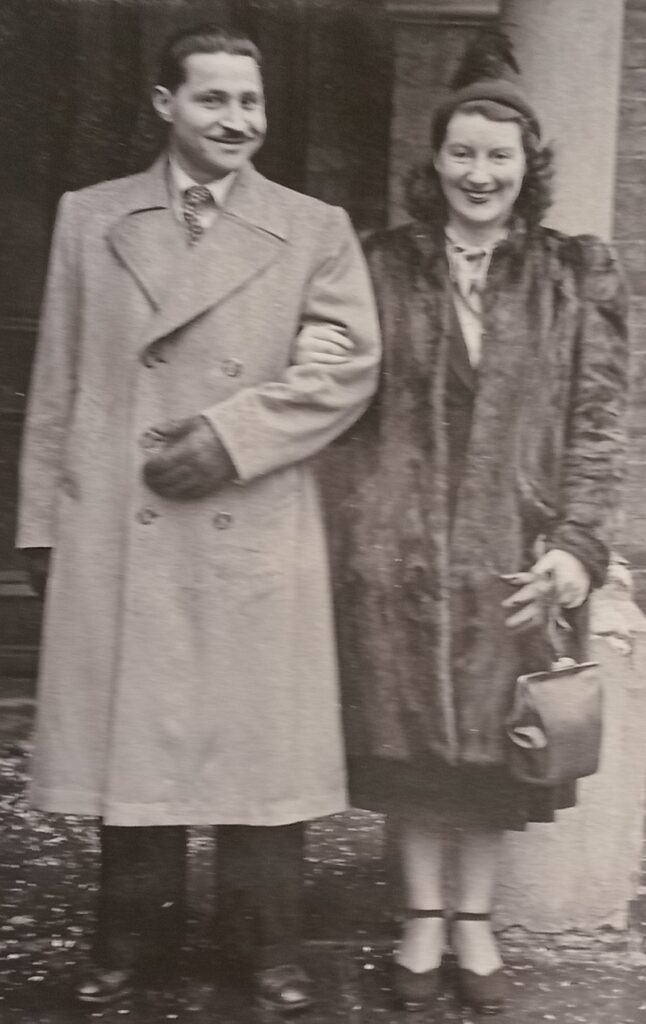

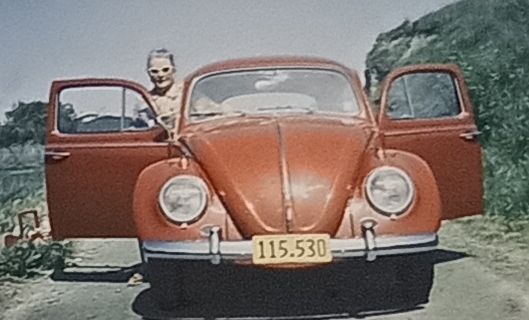

Apart from the first, the photographs here are from the exhibition of Untold Stories held at the Square Edge Community Arts Centre in Palmerston North last month. The last photograph of DPs arriving on the Goya is from the Evening Post collection held at the Alexander Turnbull Library in Wellington.

Other stories of Displaced Persons can be seen at: https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/janina-babka-iwanica/

https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/halina-kuzmiuk-aman/

https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/michal-pak-zenona-cyckoma-pak/

The Untold Stories book project has been funded by the Earle Creativity Trust and Palmerston North City Council Palmy history grant. For enquiries, and to order the book by post, please email untolds626@gmail.com.

_______________

If you would like to comment on this post, or any other story, please email editor@polishhistorynewzealand.org/