Ronald George Lipinski

Ronald Lipinski was buried with his rowing cap on 13 June 2019, on what would have been his 84th birthday. His daughter, Donna, made sure that rowing cap stayed with him, because she knew what it represented to her father.

Perhaps it was fitting that Ronald died on the evening of the Tauranga Rowing Club’s centennial dinner. His contributions to the club as a member, competitor, coach, and advocate, represented Ronald’s dedication to service in his Tauranga community, as entrenched there, as his great-grandfather’s Lipinski legacy in Carterton.

Ronald had died by the time I returned to Tauranga to tie up loose ends in his story, but his widow, Roselyn, gave me a CV he had written soon after he retired. It struck me how much he had glossed over his achievements in our earlier interview. His CV impressed me, too, for the way he recalled not only the names of his friends, his first employers and business partners, but also of every teacher he had, and colleague he had worked with.

Retirement from his surveying career could not temper Ronald’s drive, which he turned towards discovering his Lipinski roots. Each of his seven grandchildren has a copy of the resulting comprehensive family tree that he drew in the beautiful calligraphy of his professional craft.

It was a pleasure to meet Ronald and Roselyn, and I am grateful for Roselyn’s support in bringing Ronald’s story to completion. I know that there is much more that I could have expanded on, but for now, I will leave that to his children and grandchildren.

—Barbara Scrivens

FAMILY TIES

by Barbara Scrivens

Ronald Lipinski sat in his father’s car in south Carterton and watched with awe as his grandfather Bernard scythed hay.

“It was incredible watching him. My dad, Thomas, would take me down in the car and I would wait. My grandfather would start cutting, and he would put his back into it and swing that scythe, bending right down, doing one row and then another row and another. He didn’t have a tractor or anything like that. He did everything by hand.

“He had about three or four acres. Not a lot. He would do it easily. He left the hay to dry out, then got a fork, flipped it over and turned it 180 degrees. After that, he’d pick a fine day and stack it all up in the hay barn. He would have been in his seventies by then. He’d contract for other people too—scythe, and be paid for it.”

Bernard’s barn on Dalefield Road in south Carterton.

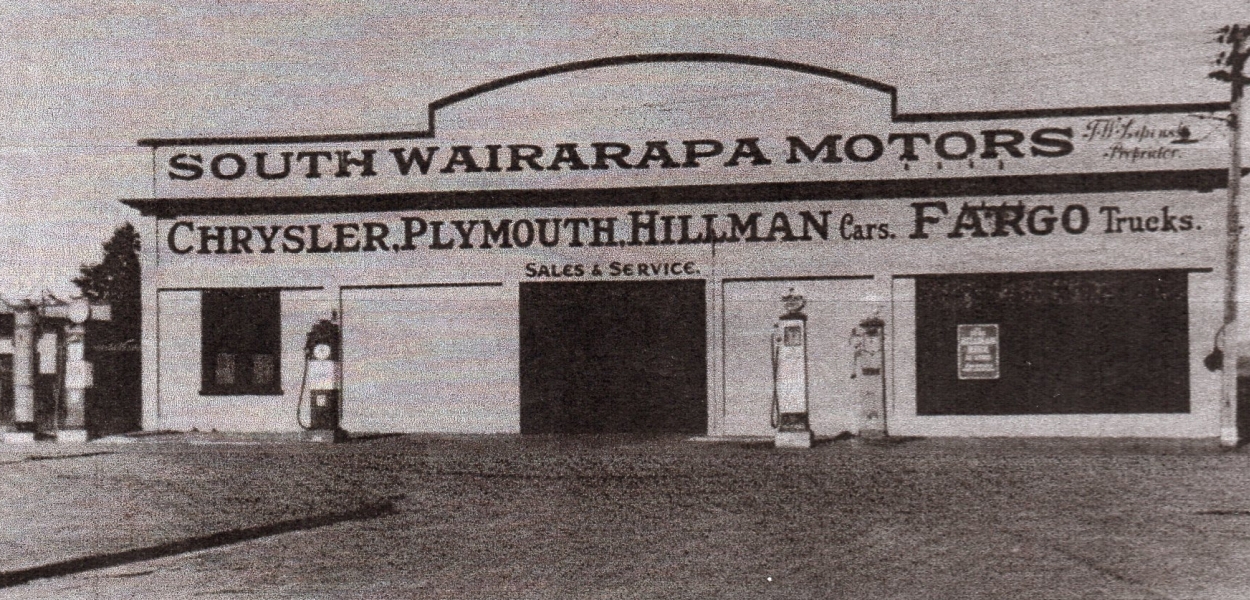

“My dad owned South Wairarapa Motors and my grandfather used to bike up to the garage, about two kilometres or more, so Dad could set the angle of the scythe. As you know, they have two handles and one blade, sharp as dynamite. Bernard would make us all shudder the way he rode his bike with that blade over his shoulder.

“He was a fascinating man. Very poor.”

_______________

Bernard Lipinski was born in 1869 in Gdańsk, in then Prussian-partitioned Poland, the second of Michael Francis (Franz) and Cecelia (née Brzoska) Lipinski’s 10 children and one of four born before the family left their homeland in 1875.

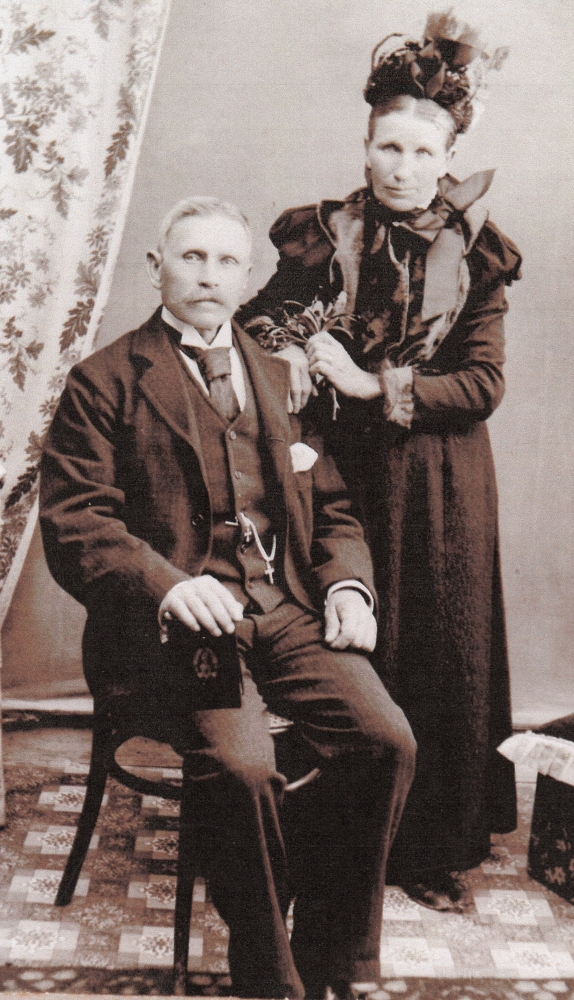

Michael and Cecelia Lipinski in the late 1890s.

The terpsichore, which left Hamburg on 15 December 1875, recorded the Lipinski family as Franz (35), Cecile (31), Auguste (9), Bernhard (6), Anastasia (3) and another apparently 49-year-old Cecile. The first “Cecile” was a misspelling, and the second “Cecile” was actually Marianna Barbara Brzoska, née Klinowska, Cecelia’s widowed mother, who was not 49.

Barbara Brzoska’s age on her headstone, 82 when she died on 19 April 1903, suggests that, for purposes of immigration to New Zealand, she made compromises to comply with the colony’s strict age restrictions: Vogel’s 1870 Immigration and Public Works Act forbade entry to anyone older than 50 “unless part of a large family group.” Barbara Brzoska played the part she needed to leave her homeland.

Barbara [Brzoska] Lipinski (as she became known in Carterton) “so carefully concealed”1 her identity, that younger members of her family did not know her true surname until she applied for New Zealand citizenship in 1901 (where she gave her age as 80) in order to receive a government pension.2

The family believes that Barbara’s husband, Jacob, was employed by the Prussian army. Cecelia, their oldest child, was born in 1844 in what was then known as Riewalde (now Rywałd), south of Gdańsk, in the Kaszubian region of then Prussian-partitioned Poland. Their second child, Johann Jacob, was born in 1846 in Klonówka, near Starogard Gdański. Five more children, Michael, Julianna, Francis, Marianna and Joseph were born in Riewalde in 1849, 1852, 1856, 1858 and 1861.

Jacob died, aged 50, on 2 May 1862, of dysentery, shortly before his mother-in-law, aged 90. Jacob’s death record shows no indication of his occupation at the time. Within six months, three of the seven Brzoska children had also died: first the youngest two, then Michael. Joseph seems to have died of emaciation, and Marianna and Michael of dropsy (oedema). Francis died three years after his father, of scarlet fever.3

In 1868, the late Jacob and Barbara Brzoska’s eldest child and daughter, Cecelia, married Michael Francis Lipinski, and her brother Johann Jacob married Marianna Okoniewska. In 1872, Julianna Brzoska married Joseph Smugai.

Although conditions for Barbara Brzoska and her family must have improved to some extent—her three surviving children grew to adulthood—infant mortality lingered: The Lipinski’s fourth child, Rosalia, died at birth in July 1874.

In 1872, Michael Francis’s younger sister, Rosalia, her husband Peter Shutkowski, and their son, Friederich, sailed to Lyttelton, New Zealand, on the friedeburg, the first ship to carry a large group of Polish settlers under the Vogel scheme.

The Smugai family joined the Lipinskis aboard the terpsichore. Julianna, recorded as another “Cecelie,” suggests a continued lack of communication between the Poles and the immigration officials. Julianna and Joseph had their three-year-old son, Franz, with them.

The Franz Lipinski–Cecelia Brzoska marriage certificate states Franz’s occupation as a soldier in the Prussian army, yet the terpsichore manifest describes him as a farm labourer. Apart from one “merchant,” all the other adult males were classified in the same way: as ordinary labourers, or, more specifically, as farm labourers. The new colony needed labourers.

The terpsichore became the last immigrant ship from continental Europe that the colonial government in New Zealand officially accepted. It sailed into Wellington harbour (then known as Port Nicholson) on 18 March 1876, and was immediately quarantined. Eight people had died of typhoid fever and the ship still carried another “upwards of a dozen cases” when it arrived. Two more passengers succumbed to the disease during the quarantine period, and one died by “accident.”4

Those who died on the journey included Marianne Bilicki (31), Anna Franzen (28), Ola Larsan (57), Frederich Lenz (48), Louise Nielsen (29), Veronica Schramka (3) and Mathilde Spora (18 months).

Bernard Lipinski’s sister Annie Johanna was one of several births aboard ship, hers on 24 February 1876. Others arrived to the Bielawski, Haftka, Taschke and Tykowski families.

Immigration officials dismissed passengers’ criticisms of the terpsichore captain, Frank Koehler, and ship surgeon, Dr Mase Buchner. In their report, Dr Alexander Johnston, John Holliday and HJH Elliot admitted that they had not inspected the ship before it landed, and were therefore unable to give a “detailed account of the arrangements ’tween decks.”

The ‘tween decks of the “Terpsichore” being so lofty and well ventilated in every respect, we were at a loss to account for the great amount of disease on board: we fear however that it is in great measure attributable to the quality of provisions and water supplied by the contractor in Hamburg. A sample biscuit has been submitted to us, and we have no hesitation in saying that it is quite unfit for food.5

Five months after the terpsichore, the fritz reuter arrived in Port Nicholson from Hamburg. New Zealand officials did not allow its passengers to disembark until the German consul, Frederik Krull, intervened. (See a fuller explanation in the fritz reuter on this page.)

Aboard the fritz reuter were Franz Lipinski’s older brother, Robert, and Cecelia’s brother Jacob, both with their families.

Robert Lipinski (37) was with his wife, Johane (38, née Caspar), and children Anastasia (9), Franz (5) and Johann (2). Robert, who had been an officer in the Prussian military, was also classified as a farm labourer.

Jacob Brzoska (29) was with his wife, Maria (née Okoniewska, 26) and Catherine (8), Franz (3) and Leonard (18 months). Catherine, later known as Katie, was actually a Grabowska, who married Thomas Salter in 1883.

_______________

Although the Lipinski brothers landed in the same port only five months apart, they seem to have initially lost contact with each other. Robert Lipinski went to the ill-fated “special settlement” of Jackson’s Bay on the West Coast where he stayed for two years. (This page has a list of Polish settlers at Jackson’s Bay and a full story.)

Michael Francis Lipinski and his family became some of the first Polish settlers in Carterton, in the Wairarapa, north of Wellington. Those first Poles understood from their German immigration agents that they would be given some land in New Zealand, and felt cheated when they discovered that land cost ₤6 an acre. In reality, the new colonial government needed them to build roads, bridges, railways, and to fell bush.

The Poles’ mistaken belief could have been attributed to a lack of education—few learnt to read or write under the Prussian regime—but for the fact that Michael Francis Lipinski could speak several languages fluently, and could read and write.

The terpsichore immigrants in Carterton took up the work that needed doing in the area, and Poles from the shakespeare and fritz reuter joined them. Michael Lipinski teamed up with other Poles clearing bush, and by 1882 had acquired 100 acres in Carterton, between Dalefield Road and Phillip Street, then valued at ₤100.6 Michael’s brothers-in-law had also accumulated land: Jacob Brzoska had 250 acres in Carterton, valued at ₤250,7 and Joseph Smugai had 100 acres in Carterton, valued at ₤100.8

Michael and Cecelia had five more children in Carterton: August Joseph in 1878, Agnes Cecelia in 1880, John in 1881, Paul Alexander in 1885, who lived for two months, and Mary Veronica in 1886.

A hand-written stone marking two-month-old Paul’s grave in Carterton’s Clareville cemetery reflects the family’s strained financial situation in 1886. Paul’s name was officially misrecorded as Saul Lipinski.

Many of the first Carterton Poles lived on Phillip Street. The Lipinski house at number 11 held the first Mass said in the town, and was used for church services until St Mary’s Catholic Church was built in 1878.

The first Poles in Carterton brought a “significant change to the all-British character of Carterton.”9 Staunch Catholics, the Poles embraced Father Halbwachs, the European priest who was instrumental in helping the Carterton Poles build a church on the corner of High Street and Phillip Street, the “centre of the Polish village.”10 It became the first Catholic church in the Wairarapa.

Tensions in the community erupted when in 1901 a new parish priest, Father Cahill, decided the church had to be moved north, away from the people who had paid for it.

The Poles felt they had good reason for their anger over the moving of the church. …they simply handed whatever money they obtained to Father Halbwachs. He would then give them enough with which to buy bread for the week, the remainder going to the establishment of the local church, and to create funds with which families might buy land to farm.11

The Lipinski house at 11 Philip Street, Carterton. It was demolished in 1987.

Father Halbwachs officiated the marriage of the Lipinski’s oldest daughter, Augusta Alice, to John Chapman in 1883.

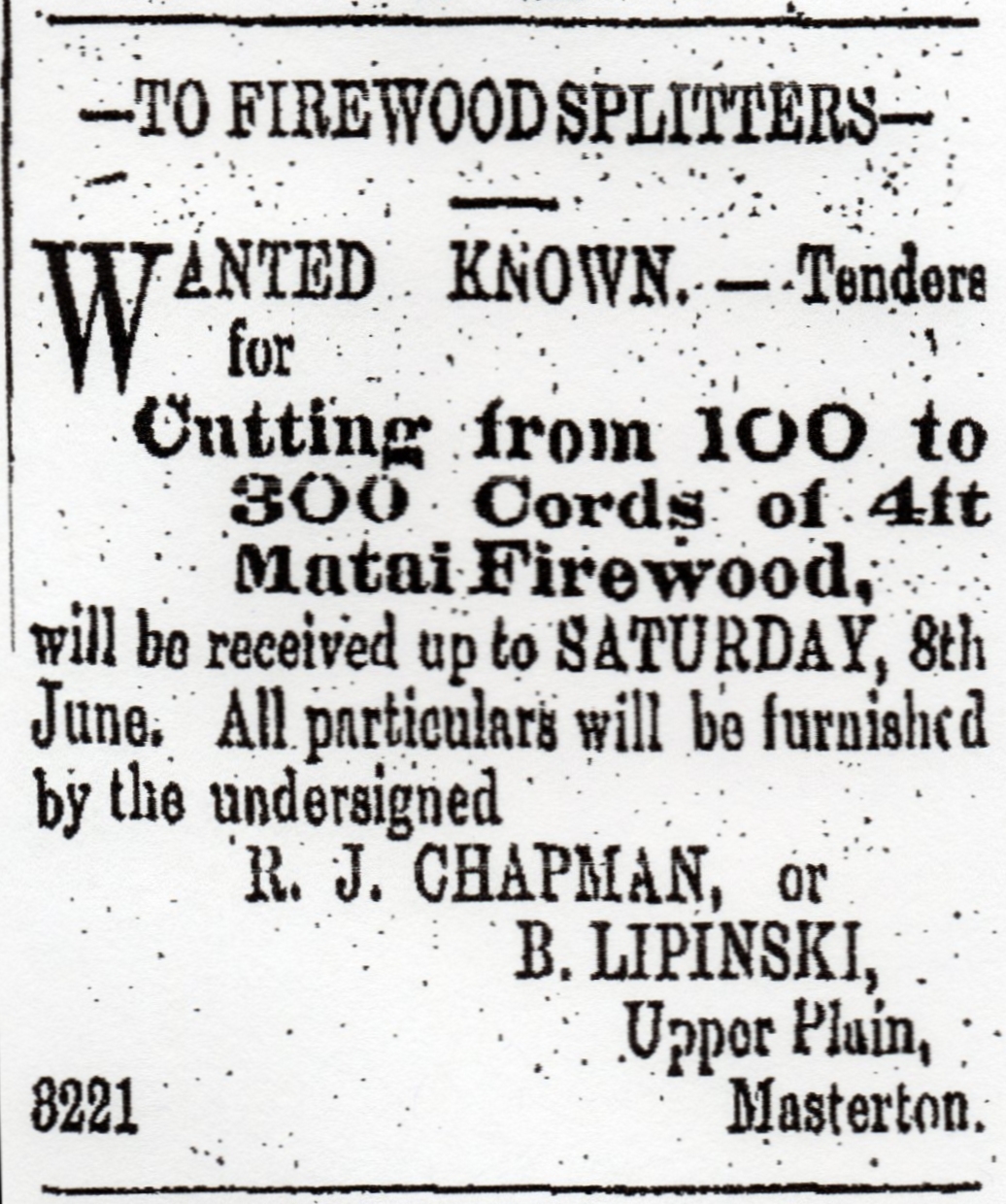

This advertisement in the wairarapa daily times shows Bernard in business with his brother-in-law in 1889.12

Brothers Bernard and August Lipinski each took over about 10 acres of the family farm, Bernard on the Dalefield Road side and August the Phillip Street side. Both had to repay half the value of their land to their father for distribution among their sisters.

_______________

By the time Ronald George Lipinski was born in 1935, his great-grandparents had been dead for 17 years. Michael Lipinski outlived Cecilia (the spelling on her headstone) by six months.

Michael Frank Lipinski around 1915. He became naturalised in July 1887.

Cecilia’s death notice in the new zealand times on 17 June 1918 stated that, apart from a year since she arrived in New Zealand, the “old settler” had lived in Carterton. As well as her five daughters and three sons, she left 30 grandchildren and nine great-grandchildren.

Bernard married Emily Hall in 1896. They had five children, Ronald’s father, Thomas William, the fourth and first son, born in 1912.

Emily (née Hall) and Bernard Lipinski.

Emily died in January 1926 when Thomas was 13 and his brother, Bernard Frank, 10 years old.

Bernard’s and Emily’s three daughters, Barbara Rose, Kathleen and Olive Maud, were 30, 27 and 21 when their mother died and no doubt helped raise their younger brothers.

_______________

Thomas married Nancy Welch in Carterton in 1934. Ronald was the elder of their two sons. David was born in 1941.

“We lived in Clifton Avenue. There were about 10 houses on each side of the street, with a parking area at the end of the road near the railway, which used to come down the valley.

“We knew everyone in that street. I could walk from one end, where it joined High Street, the main highway through Carterton, and, through a series of little gates or turnstiles, I could do a loop right around that street. I would cross at the end and get back to High Street without stepping on our road, because everybody had a common or useable way of getting over their boundaries, whether it was a gate or a hedge or just a gap.

“When I was born my nanna, Edith Welch, came down from Masterton to look after me so that Mum could carry on running the office at the garage. My playmates were the McFarlanes, Gary Parker, whose family owned the farm at the end of the street, Shirley Harrington, who lived next door, and Billy Worsfold, who lived about five houses towards High Street.

“We caught freshwater crayfish in the creek that ran through the Parker’s farm. In 1940 I started school at the Carterton Main School. It closed in 1942 and I went to the new school in the middle of the town.

“I remember the air-raid drill and having to run outside and hide in the slit trenches that were dug around the school playing fields. We used to get a pint of milk every day, which had about a half an inch of solid cream on top, and in season, we used to get an apple a day.

“In about 1945, we shifted to a house on Park Road, on the corner of Armstrong Avenue, much closer to the garage and my school. I spent a lot more time at the garage, sweeping floors and counting petrol coupons for Mum at the end of the day.

“In 1947 I started mowing lawns for some of our neighbours. I used to get one shilling from Mrs Armstrong, two shillings from the mayor, Mr Taverner, and one and sixpence from the Kings next door. Some days I would play with Porky Lynch on his farm down Park Road.

“I can remember standing in the back yard one day to see the first jet powered aeroplane in New Zealand, a Gloster Meteor, flying down the line of the main road.”13

The Thomas Lipinski garage in Carterton.

“When the polio epidemic broke out in the summer of 1947–1948 the Education Board said forget about schooling: ‘Get your children occupied in some sort of way, as an orchardist or a painter, anything.’ Once they knew it was no longer contagious, we could go back to school.”

A neighbour who owned an apple orchard south of Greytown employed Ronald until the school term started. One lunchtime, 12-year-old Ronald mistook a bottle of Australian 80 percent-proof cider for apple juice, and later woke with the doctor at the side of his bed.

The school term started on 1 March 1948 and Ronald became one of the youngest scholars at the Wairarapa College in Masterton. A three-carriage steam train ran to and from the school, and provided “some very exciting trips, especially the grass fires during the summer.

“That Christmas my dad said to us, ‘I’m going for a ride in the caravan.’ He had built his own.

“We all hopped in, my mum and I, and David. We didn’t know where we were going. We went right up to Northland, to the North Cape, down through the Bay of Islands, and around the Coromandel Peninsula to Tauranga and Whangamata. At every place we went to, dad hunted out the tractor dealers and asked them about business in their towns.

“Dad had had an enquiry from CB Norwood and it pushed him to look for something different. To some extent, I think he wanted to get away from the Carterton area.

“In Tauranga he saw the owner of a tractor agency, Harvey Drew, who went to live in South Africa. They came to an amicable arrangement: Dad sold the Ferguson tractor agency in Carterton and within six months was running his own garage the same size in Tauranga, Tauranga Motors.

“In July 1950, when Dad started at Tauranga Motors, I started at Tauranga College. The school was three years old, co-ed, 350 pupils, no discipline, no tradition, expanding rapidly, and completely different from Wairarapa College. Nobody knew me, so I just went for it.

“For summer sport, I had the option of cricket, tennis or rowing, so rowing it was. I went home with a permission form for Mum and Dad to fill in, for me to do swimming, rowing and water sports. I loved it. I was in my element.

“In later years I instigated the relocation of the Tauranga Rowing Club boathouse from Dive Crescent to Memorial Park. This created a lot of public opposition and the council employed a commissioner to hear my submission. After we built the new clubhouse everybody thought it was great.”

Ronald passed his School Certificate but failed his University Entrance the following year, thanks to a 37 percent in English, “as did everybody who sat, because we had been taught the incorrect course.”

The extra year in school gave Ronald the chance to develop leadership—he became one of four prefects—and his love of rowing, rugby and shooting. He received school blues for all three sports.

In January 1953 Ronald began four years’ articled to a Tauranga surveyor, which led to his intimate knowledge of the contours of Murupara, Kawerau and Whitianga.

“I worked very long hours. It was really slave labour. We did a lot of boundary locating in the heavy bush for the sawmilling companies. On the first day of the Murupara survey, the site was just a big paddock. We camped at the Kaiangaroa forestry single men’s camp, and after 12 months the Ministry of Works established a workers’ camp in Murupara, where we stayed for the next two or three years.

“The weather was either frying hot or freezing cold. Towards the end of the job, a public hall had been built and films were shown on Friday and Saturday nights. There could be 20 to 30 horses tied up outside when the films finished. Some of the Maori used to being eels and watercress for the cook, so we got pretty tired of eels and watercress for dinner.”

Ronald appreciated the solid grounding in surveying procedures but realised it came at the expense of engineering experience. A chance chat to another surveyor, two years after he had finished his articles, solved his “restlessness” when that surveyor gave him the opportunity to pursue more varied work with tellurometers. Ronald became the regular operator for set 352.

“The majority of the work was ground control for aerial mapping. The largest contract was for New Zealand Forest Products at Kinleith. We camped in Tokoroa, and got into some remote areas within the forests.”

Before he qualified in 1964, Ronald had also been involved with urban surveying closer to home, such as the Queen Elizabeth II Youth Centre, Tauranga Hospital, Tauranga harbour’s Mount Wharf, Sulphur Point Wharf, and the Cutter Channel.

_______________

Thomas Lipinski had been a Wairarapa provincial rugby representative and later coached rugby in Carterton. (Ronald admitted to being “only average” before moving to Tauranga.)

After school, his long work hours forced Ronald to give up rugby, but through sculling, he was able to continue his involvement with rowing. He recalled a “very successful” 1960/1961 season with John Bickers, which culminated in their winning the Maiden Double Sculls New Zealand Championships in Oriental Bay, Wellington.

Ronald’s rowing had by then also extended to coaching, which in 1962 included a team of nurses from Tauranga Hospital.

“One of them was simply superb. She came from Rerewhakaaitu and her name was Roselyn Mary Lewer. She proved extremely hard to catch.”

Ronald and Roselyn married the following May, and started their own family. The responsibility of marriage and his first child, Donna Mae, pushed Ronald to complete his surveying exams and registration with the New Zealand Institute of Surveyors in November 1964.

_______________

The Lipinski name was well-known in Carterton. Possibly thanks to his ability with the language, Michael Lipinski became a leader of the Polish families sent to Carterton from the terpsichore, and those who joined them.

It is not clear exactly why Thomas decided to move his family away from Carterton. He would have been aware of the history, but he married a non-Polish non-Catholic and did not follow any of the Polish traditions. Ronald believed he needed some anonymity, and took advantage of the offer on his business to settle in a warmer climate. He soon found, however, that even in Tauranga his surname conjured up bigotry.

“One man who Dad got to know asked him to turn up at the Field Days’ Motor Traders Association stand. Dad went along, and when he found out that the next one had come up, he asked that man what time it started.

“‘It’s not time for you, Tom, there’s a couple of them don’t like your Polish upbringing.’ He was barred from attending. I know that Dad was very hurt about that.”

Ronald had a similar experience.

“I was in a surveying business on Devonport Road. Two members from the Mt Roskill [Auckland] Round Table, a young men’s service club, approached me about establishing in Tauranga. They said, ‘Ron, you should join Round Table because there is a lot of contact with other business people. We’ve got a meeting tonight, and next week we’ll get back to you.’

“One of them did. He looked a bit sheepish, and I said, ‘What’s the trouble?’ He said, ‘You’re out of the club. Your name is not acceptable.’

“It was a bit unpleasant, but it didn’t stop me from joining. As I was not able to get into Jaycees, I welcomed the opportunity to join Round Table. I didn’t feel any different from those other boys. I found out that the original objector was not popular with the other members, who were disgusted with his reasoning. It was a personal thing, but that was the only problem I experienced with the Round Table.”

At the inaugural meeting of the Tauranga Round Table, on 10 August 1966, Ronald was given the honour of moving the motion that the club be formed. With Ronald as its Community Service Convenor, the club constructed a senior citizen’s lounge in Willow Street, for which it received the Round Table’s Rose Bowl for best national community service project of 1967. Ronald retired from the club as chairman when he reached the age-limit of 40 in 1975.

A decade earlier, Ronald’s already busy surveying, coaching and Round Table life became even busier when Roselyn presented him with his first son, Murray Thomas, in November 1966. Seven months later, Ronald and a partner decided to establish a 64-hectare pine plantation on a steep block of land known as Old Baldy in Welcome Bay. The arrival of Paul Richard in August 1968 pushed Ronald to more immediate domestic matters: he extended the family home.

In February 1971, as his then business partnership deteriorated and his pine-planting partner withdrew from the project, Wayne Andrew Lipinski “entered our world and turned it upside down.” The business partnership ended, and Ronald set up on his own from Tauranga Motors’ showroom.

“I had no jobs, so helped Mum with office work, and the garage paid me a small wage so I could buy food. I had only been going a few weeks when I was visited by Brian Shrimpton, who thought it was silly for the two of us to be running separate offices.”

Other partners joined and left, and the firm officially became Shrimpton & Lipinski on 21 December 1973. The company embraced aerial mapping technology and quickly expanded, due in large part to the work it received from the burgeoning local kiwifruit industry.

As his family and the Old Baldy trees grew, Ronald became more involved with school committee meetings and silviculture on the pine plantation, on which they planted 157,000 seedlings. Increased rent forced him to sell the lease in 1981.

As if his workload was not enough, in 1982 Ronald bought four hectares in Cambridge Road, “did some contouring and planted out about 60 avocado.” A year later, he and Brian Shrimpton bought a farm on Pahoia Road, which they part sold, to offset costs, and part planted out in kiwifruit. Ronald noted that although he didn’t involve himself with the Pahoia farm, “it was very hectic mowing grass on two orchards.”

Ronald Lipinski, seated third from left, with his staff at his surveying, civil engineering and town planning firm, Shrimpton & Lipinski, in 1988. Ronald retired in 1998. Today the firm is still operating, under the name S&L Consultants Ltd.

_______________

Thomas William and Nancy Lipinski on the occasion of their 50th wedding anniversary on 15 November 1984.

Thomas had a heart attack in 1980 and retired, leaving control of his motor mechanic business to David. Thomas had a stroke two years before he died in 1986.

Ronald: “He was held in high regard within the Tauranga business- and especially the farming community. I never heard a negative word about him. He had very little education after his mother died, but he had a deep understanding of life.”

At his funeral, Father Ryan called Thomas “a simple man, but a man of the world.”

Thomas may have had a Polish surname but, despite what the Tauranga man mentioned earlier had surmised, he did not have a Polish upbringing. Bernard Lipinski seemed happy to let his wife bring up their children following her English faith and traditions. None of them married Poles and, because Thomas was a non-practicing Catholic, his children grew even farther away from the Polish faith and traditions.

Thomas’s Polish surname ended up bearing no definitive relation to his ethnic origin.

“It was a matter of some personal life insurance. To claim it, Dad had to produce a copy of ownership or title. He didn’t know where his birth certificate was. He couldn’t remember ever having it.

“He went to Carterton to talk with the priest. They did resolve it, but it wasn’t what he expected.”

In 1912, Emily Lipinski worked in the annexe of the Carterton nursing home, and knew of a baby born to an unmarried young woman, who Ronald believed was probably Australian. The father had apparently been a serviceman who had “returned home,” probably to England, and may not have known of the pregnancy. Emily and Bernard adopted the baby boy, “accepted by all,” and whom they named Thomas William. Then, Bernard’s and Emily’s three daughters were 16, 13 and seven.

Ronald knew nothing of his father’s birth parentage until his extra time in retirement enticed him to start researching his family. His mother died only six months later, before he had questioned her for specific information.

“I was going through her papers and finding information… I’d go into a cupboard and papers would fall out, like a letter from mum setting out her gifting after she died.”

In a box of “bits and pieces,” he found a letter written by Thomas’s birth mother to his adopted mother. The handwriting is elegant:

… I am pleased baby is getting along nicely. I won my case in Wellington… Of course I have to wait three months before it is finally settled… about a pram… I will send you the cash to buy it and could you remember how long ago it is since you took baby from Mrs [—]? If you do, would you write and let me know because I fancy I owe her some money. I will call and see you as soon as possible…

The wealth of details carried on other family papers that Ronald had previously not known about induced him to make the same trip his father had done, to the Carterton parish priest. When Ronald asked to view his father’s birth details, the priest told him the church was not obliged to divulge the information, because it was a “private” matter.

“The priest went through the register of births, deaths and marriages. There was a gap, and I realised it was dad’s entry.”

_______________

During his research after his mother’s death Ronald discovered four more uncles that he did not know about: Several years after Emily died Bernard married Norah May Portsmouth.14 Donald Neil Lipinski was born in 1929, another Michael Francis, known as Frank, in 1931, John Maurice in 1932, and Brian Scott in 1934.

They were living in a “six-roomed residence” in Dalefield Road, South Carterton, when it was destroyed by fire in 1933.

Fanned by a strong gale the flames quickly demolished the building which was situated outside the water area and the brigade had a difficult task.15

Frank and Brian continued to live in Carterton but Donald moved to Warkworth and John to Whanganui. John returned to Carterton and died there in 2018, as did Brian later in the same year.

Roselyn: “We got in touch with Donald, and went to see Frank on the farm in Carterton, and Brian came to see us there, but we never met John.

“When Dad died there was this strange man at his funeral. He came to the house afterwards. He didn’t speak to many people and he disappeared before we had a chance to approach him. We now know he was probably John.”

_______________

This photograph commemorated Ronald’s and Roselyn’s 25th wedding anniversary in 1988.

Ronald had no regrets about his father’s decision to leave Carterton. Tauranga held one attraction that Carterton could not compete with: the sea.

As for the Lipinski name, Ronald was grateful for the way it led him to so many and varied family ties and new relationships all over New Zealand.

© Barbara Scrivens, 2019

THE PERSONAL PHOTOGRAPHS ARE FROM THE LIPINSKI COLLECTION; OTHER IMAGES ARE CITED BELOW.

THANKS TO THE NORTH AUCKLAND RESEARCH CENTRE IN THE TAKAPUNA LIBRARY FOR THE LOAN OF ITS AUDIO RECORDING EQUIPMENT.

ENDNOTES:

- 1 - Brzoska, Ellen and Stanley, Descendants of Johann Jacob Brzoska and Marianna Barbara Klinowska in Poland, New Zealand, and the United States, privately printed in 1994, page 70.

- 2 - First introduced in New Zealand in 1898 by the Seddon government.

- 3 - Thanks to the European Interest Group of the New Zealand Society of Genealogists for interpreting the

death records,

Level 1, 159 Queens Street, Panmure, Auckland, www.genealogy.org.nz. - 4 - AJHR, 1876, D-3, IMMIGRATION TO NEW ZEALAND (LETTERS TO THE AGENT-GENERAL TRANSMITTING REPORTS UPON IMMIGRANT SHIPS), page 41.

- 5 - Ibid.

- 6 - The CD, A Return of the Freeholders of New Zealand, October 1882. Page 21 of the L section

says “Franz Lepienske, settler, Carterton.” It is not clear whether the same number of acres attributed to a

“Franz Lipienshi” of Carterton on page 28 of the same section means he bought two sets of land.

The CD is available from the New Zealand Society of Genealogists. - 7 - Ibid, section B, page 78. The return spells the name Broska.

- 8 - Ibid, section S, page 60.

- 9 - David Yerex, Carterton, Biography of a Country Town & District, 1999, pages 38-40.

- 10 - Ibid.

- 11 - Ibid.

- 12 - Wairarapa Daily Times, 4 June 1889, Page 3, Advertisements.

- 13 - The Royal Air Force loaned the high-altitude, high-speed fighter jet Gloster Meteor to the NZRAF in 1945 to allow the latter’s fighter squadrons to become acquainted with its jet propulsion and manoeuvrability. After assembly, tests, and displays in Auckland, it toured New Zealand from 22 March 1946.

- 14 - The family story has Mathew as her maiden name.

- 15 - Opunake Times, 14 February 1933, page 3, Advertisement Column.