The Kuklinski Family

There is no doubt that when Jacob and Ellen [Eva] Kuklinski moved into James Street, Inglewood, with their eight children, the area’s noise, fun and warmth levels increased by several notches.

The Kuklinskis were no strangers to the area. Although they had all grown up in rural central Taranaki east of Inglewood, in Ratapiko and Waitui, three generations of their family had attended Inglewood’s Catholic Sacred Heart Church, and they regularly visited friends and family nearby.

Bernadette, or Benna, the eldest of the eight Kuklinski siblings, was 21 when the family moved “into town.” Her youngest brother, Patrick, or Pat, was seven.

Benna was born on 30 November 1929, and Pat on 6 June 1944. Between them were Pauline, born on 1 May 1931; Joseph, or Joe, born on 28 December 1932; Gertrude, or Gertie, born on 16 September 1934; Thomas, or Tom, born on 22 October 1936; Peter, born on 29 October 1939, and Michael, known as Mick, or Skin, because of his naturally thin frame, born on 16 April 1941.

Sister St Martha Szymanska encouraged me to interview Benna and Gertie, who still live in the family home, and after I went back to them with an early draft, they suggested that I chat with their brothers Joe and Pat, who both live nearby.

This is a story that starts in Kokoszkowy, a little Kaszubian village in Pomeranian northern Poland, and the decision made by several families in 1876 to leave their land—under Prussian occupation—in the hope of making better lives for themselves across the ocean. It is also a story of strength and deep love for family.

I thank Benna and Gertie, for their time and generosity to a stranger, and Joe and Pat, who added extra spice to their sisters’ recollections.

During my second visit, I heard that their sister Pauline Fraser had been taken to Taranaki Base Hospital in New Plymouth. By the time I returned two days later with the photographs I had borrowed, she had died peacefully, on 7 August, 2019, and the family had rallied in support.

This family can teach us all.

With love and respect—Barbara Scrivens

BERNADETTE & GERTRUDE KUKLINSKI,

with interjections from their brothers Joseph & Patrick

by Barbara Scrivens

Jacob Kuklinski and his wife, Barbara (née Machalińska), lived on a 69-acre farm on the Kaimata Road, Ratapiko, in Taranaki. Frank Dravitzki and his wife, Mary (née Fabich) had 76 acres barely a mile away.

In the 1800s, the families lived in the same village, Kokoszkowy, in then Prussian-partitioned Poland. Drzewicki and Fabisz names witnessed the Kuklinski’s October 1869 marriage. The Kuklinskis and Drzewickis (and Fabiszes) immigrated to New Zealand on the same ship, the fritz reuter, in 1876. Marie and Franz Drzewicki, as their names appeared on the passenger list, had two young sons, Vincent and Johann.

They settled on the eastern side of Mount Taranaki with other Poles from the fritz reuter.

Benna: “When granddad Kuklinski—we called him Lul and granny Lula—first came to Taranaki, he worked on the railway line with the other Poles. They found out that they could buy land in Ratapiko, and that’s what they did. Grandad couldn’t afford that much, but some of the others had quite big places.”

Within six years, both Jacob Kuklinski and Frank Dravitzki, as he became known, were listed among the landowners of the new colony.1 Other Poles with land in Taranaki in 1882 were Bielski, Bielawski, Biesek, Dodunski, Dusienski (Duschenski), Fabish, Habowski, Labowski, Lewandowski, Meller, Mischewski, Neustrowski, Potroz, Rogacki, Stachurski, and Wisniewski.

The Dravitzki family grew, with Elizabeth, Francis, Joanna, Joseph and Mary joining their brothers. Johann became known as John and Joanna as Jane. Jacob Kuklinski was Francis’s godfather.

Frank Dravitzki died on 31 December 1886, aged 40, and became the first entry in a list of deaths that Joseph Fabish2 began compiling among his neighbours in the Inglewood area. Barbara Kuklinska died on 13 May 1889, when she was 43.

Jacob Kuklinski’s second marriage, on 29 June 1889 to Mary Dravitzki, was the first entry on Joseph Fabish’s list of marriages among his neighbours.3 According to family story, Mary had been housekeeping and for her childless friends of many years, as well as taking care of her seven children, then aged between 16 and three.

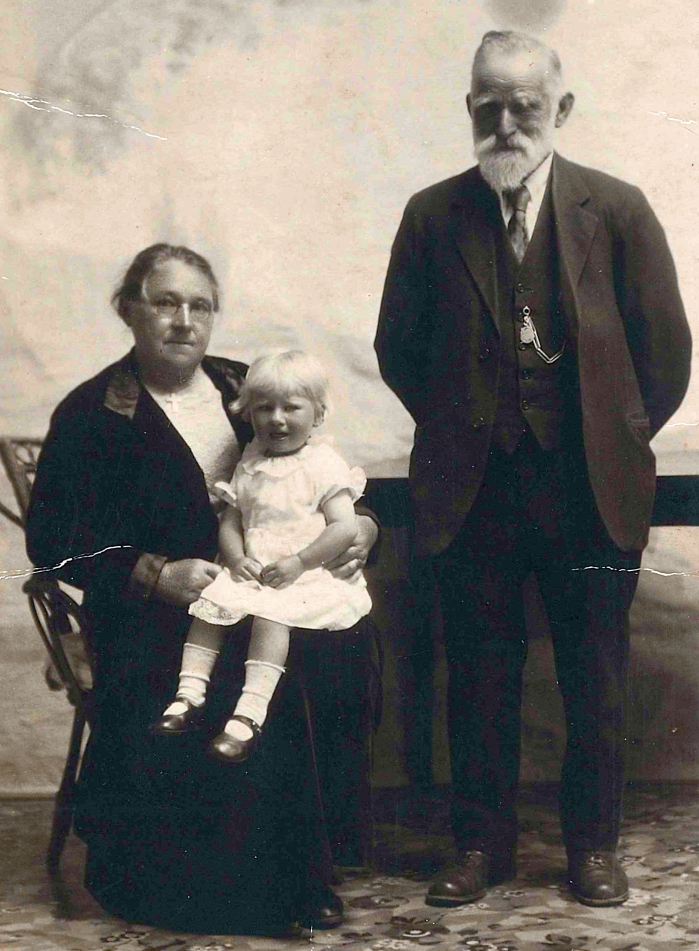

Jacob and Mary (née Fabish, then Dravitzki) Kuklinski.

Jacob Kuklinski embraced his new role as stepfather, and he and Mary had four of their own children: Anne in 1890, Michael in 1891, Jacob junior in 1893, and Kate in 1895.

Anne Kuklinski, Jacob and Mary’s first child, became Sister Mary Koska.

Jacob and Mary Kuklinski with their family, probably in 1909, commemorating Jacob and Mary’s 20th wedding anniversary. Jacob junior is standing at the back on the far right. Next to him is his older sister, Anne, and then his older brother Michael. Kate is seated in front

Jacob Kuklinski junior married Ellen Eva Potroz on 29 January 1929.

Benna: “Grandad [Thomas] Potroz wouldn’t let the young ones speak Polish. Our mum’s brothers used to say their rosary in Polish, and mum used to tell us that they laughed at them—Mum and her sisters, aunty Millie and aunty Pat, when they were saying theirs.

“Grandad Potroz said, ‘That’s the last. No more Rosary in Polish, and then Mum didn’t learn.”

When Eva Ellen Potroz (Ellen) was born in 1905 to Thomas and Mary (née Stachurski) Potroz, she joined sisters, Apolonia Martha (Polly, then 16, who became Sister Mary Dunstan) and Mary Ann (May-gee, then 10), and brothers Thomas Joseph (Tom, then 15), David John (Dave, then 13), Bernard (Ben, then 12), Frank Xavier (Frank, then seven), Anthony Joseph (Joe, then five), and Michael Lewis (Mick, then two).

Ellen Kuklinski’s eldest sister, Apolonia Martha Potroz, became Sister Mary Dunstan.

“Mum’s sister [Mary Ann], who lived next-door, used to call me Ben-gee. I said, ‘If I’m Ben-gee, you must be May-gee and uncle Joe [Biesek] must be Joe-gee,’ and that’s what they were called from then on.”

_______________

Jacob Kuklinski senior died in 1918, remaining true to his Polish roots. Aged 67 and after 41 years in New Zealand, he gave Poland as his place of birth for the Alien register that the New Zealand government required of non-Britons living in New Zealand during WWI. Mary is listed with him.

“Dad lived with his mother until he got married. She couldn’t talk much English, so Dad spoke Polish and learnt English when he went to school. He was 35 and mum was 24 when they married. Mum could understand Polish but she couldn’t speak it. Dad used to talk to her in Polish when he didn’t want any of us kids to know what he was saying.”

After Jacob Kuklinski’s half-sister, Jane (née Dravitzki) Bilski, died of diabetes, aged 30 in 1912, the youngest of her five children, two-year-old Thomas Bilski, joined his grandmother Mary’s household.

Benna: “When aunty Jane died, uncle Valentine [Bilski] decided he couldn’t cope. Dad wanted his mum to take the youngest girl too, but uncle Valentine wouldn’t let her go.”4

Gertie: “In in those days, somebody would die and they’d have to manage. When I was going to school, just about every family had somebody else’s kids living with them because someone had died.”

Their grandmother Mary Kuklinski died in 1933, aged 81.

Mary Bernadette (Benna) Kuklinski, with her Potroz grandparents, Thomas and Mary, née Stachurska. Benna was their third grandchild, their first granddaughter, and the first child born to one of Thomas and Mary’s five daughters.

Bernadette remembers Thomas as adult when she was young. She and her siblings, Pauline, Joe, Gertie, Tom, Peter and Michael, were all born at the Kaimata South Road farm. Pat was born in Ratapiko in 1944.

Jacob Kuklinski junior’s older brother, Michael, took over their mother’s farm on Kaimata Road South. Jacob junior and Ellen lived farther along the same road, opposite Jacob’s eldest half-brother, Vincent Dravitzki.

Benna: “Dad was always telling us he wanted to buy the farm from uncle Michael, but he wouldn’t sell it to him. He sold it to Walter Bracegirdle. He probably got more from him that he would have got from Dad.”

Years prior, Jacob Kuklinski senior had created ponds to drain and improve the land he had.

Benna: “On the cowshed side of the house, Dad built a bridge to take the horses across. I remember one big flood coming from from Mum's sister's place place at the back, into these two ponds. The water came right up to the poplar tree where Mum used to hang the clothes out on the line. One of the boys fell in, Tom I think it was, and mum had to drag him out. Just about every one of the boys fell in the blooming creek.

“Dad took one pond away and left the big pond and a drain, quite deep, because of the water coming from aunty May-gee’s.”5

Gertie: “Dad cut a big tree, and that’s what you walked across to get from one paddock to the other.”

Except that Jacob and Ellen’s children did not often walk across the log, 30–40 centimetres wide, which Jacob had sawn flat.

Joe: “If you were going to get the cows, you’d run across.”

Benna: “One day Mum went to get the cows. Dad was haymaking so she took all the kids with her. Joe and the dog somehow managed to fall off the bridge together and Mum had to get him out.”

Gertie: “I fell in it too, but Pat didn’t. He wasn’t born on the farm.”

Joe, Benna, Pauline and Gertie in 1936. Benna: “Mum had been to town and came home with gym frocks that she bought us for school. She had met a photographer in town and had arranged with him to photograph us. She put Gertie in a dress that her godmother, aunty Joyce Potroz [née Turchie, who married Thomas Potroz junior in 1927] had given her, and sat us all on the kitchen bench.”

Gertie: “When Dad was in school in Ratapiko, there was one English family in the whole area. A lot of Poles settled in Ratapiko: the Roguckis, the Stachurskis, the Burketts.”

Benna: “We walked to Ratapiko School—only five miles—along Kaimati Road South, up Tariki Road, up the hill, then down again…”

Gertie: “… round the corner, and there we were.”

Benna: “Then Dad and Walter Bracegirdle got their heads together and arranged it with the Education Department for a school bus that left from Tariki. There were easily 30 of us on that bus.”

Gertie: “We had about 30 cows. We used to milk them by hand. Dad had a cream can, and all the cream went there. A truck came to pick it up. It was all used for butter in those days.”

Having extra mouths to feed did not faze the Poles, who continued their tradition of living off the land: they ate what they produced.

Gertie: “We grew all the vegetables under the sun, cabbages, cauliflower, potatoes, everything.”

Benna: “Dad used to have pigs, and they had chooks and ducks and geese. They’d share a pig or cattle that they killed with aunty May-gee and uncle Joe-gee. They used to make a brine, and three kinds of sausages: pig’s blood sausage, liver sausage and one they made with all sorts of pieces of pork [kiełbasa]. They’d hang them from the kitchen ceiling, high up.”

Pat: “The meat used to go up in the safe. To keep it cool, they’d pull it up into the big macrocarpa tree down by the woolshed, underneath the bottom branches. There were no fridges in those days, and the safe had holes in it, bird -netting, so the fresh air circulated around it.”

Benna: “At the Kaimata farm, when we didn’t have our own bacon, Dad used to get it from the factory in Inglewood when he took us to catechism.

“When I was about seven, I said to mum, ‘Can I come to the shed and milk?’ She said, ‘If you want to, but first ask Dad,’ and later Joe said that if I was going to the shed to milk, he was coming too, and he was just five.”

Joe: “I wanted to help Mum and Dad. They had no milking machines; they had to milk by hand.”

Benna: “Joe and I used to get up in the morning, do the milking with Mum and Dad, and then we’d have a meal—Pauline used to cook our breakfast porridge, and Mum used to make our lunches—then we’d all catch the bus and go to school. And Joe and I, we’d go back to the shed at night, after school.”

Joe supplemented his diet with opportunistic forays around the farm. By the time the family moved to Inglewood, he had developed a reputation in the family for purloining eggs.

His mother told his wife, Patsy (née Evetts), how Joe had once collected all the chicken eggs that he could find at their Inglewood home, boiled them, and ate them “before anyone else got near them.” When they were first married, Patsy discovered that only six poached eggs at a time would do, or, if scrambled, 12.

Joe: “I had to look after myself. I had two older sisters and one after me, so I had to learn to look after myself.”

“When the plum and the apple trees were ripe, I’d go and climb them.”

Benna: “Dad had made some blackberry wine and Joe found it. How he got up that high in the cupboard, we still don’t know. Mum ran to her sister next door and asked, ‘What can I give to a drunken kid?’ Grated green apple, apparently, did the trick.”

_______________

The Kuklinski family circa 1950: Standing from left are: Gertrude, Joseph, Thomas, Pauline and Bernadette. Seated are: Ellen (née Potroz), Patrick, Michael, Peter and Jacob.

Benna: “We were the youngest of the Polish settlers. When we were little, the Poles were already shifting out of the area; they were all older than us.”

Gertie: “In school, we were the Polish ones and well more than half the school were ordinary New Zealanders. And the ones who were Polish, weren’t talking Polish. We didn’t know any Polish; we were never taught. Dad was going to teach us, but we laughed one day, and he said, ‘That’s it, I’m finished. I’m not telling you any more.’”

Benna: “He forgot his Polish. When those Polish people came out in the war, he used to say, ‘I can’t understand them.’”

The differences in dialects between the 733 Polish children and their 105 caregivers, to whom the New Zealand government refuge in 1944, and the Taranaki Poles of the 1870s is understandable: they come from opposite sides of the country. The early Polish settlers in Taranaki originated from northwestern Poland, and spoke Kaszubian and Kociewian. The WW2 Poles came from what was then still eastern Poland.

There had been a family story that Jacob Kuklinski senior came from Kraków, but a second cousin, née Jeanette Kuklinski (Michael Kuklinski’s granddaughter), found out the truth.

Benna: “She told me how her dad, our dad’s nephew, John [Kuklinski], got her a job at the Bank of New South Wales—closed now—in Rimu Street, Inglewood. One day the bank manager said to her, ‘If you’ve ever got nothing to do, have a look in the archives.’ She had a look, and found that granddad Kulkinski, Jacob, was the first Polish person to deposit money there.

“She went home to her father and said, ‘Dad, I know where great-granddad comes from.’ The archives said that Jacob Kuklinski was Polish, and he came from Broda. That was a surprise.

“Jeanette, her sister Maree, and Maree’s husband went to Poland, drove to Broda, found this church, looked through the cemetery, and saw a lot of Kuklinski names. They met a man in the cemetery who wanted to take them to meet some living Kuklinskis, but they couldn’t, because they had to get back to Danzig.”

_______________

Benna: “The doctor told Dad that he had to get off the land for the sake of his health, and we sold our little farm [in Kaimata Road South]. Dad sold all his cows and nine of us were living in a house on the Ganaway’s farm, nine of us because Pat wasn’t yet born.”

“Once we shifted to the Ganaway’s in Ratapiko, we didn’t go by bus to school anymore, because we lived so close. That was when I went home for lunch. I never took lunch to school, because I liked to go home to have lunch with Mum.

“I didn’t like school. I was 14 when I left to look after the kids when Mum had Patrick, and I liked it. Instead of school, I could listen to the radio serials.”

Gertie: “There was an old lady who lived just down the road from us, Mrs Topping. School was only about a quarter of a mile away then, and she used to stop me on the way and say, ‘Come on in, I’ll give you some breakfast. Those bloody boys are eating too much!’ She’d take me in, give me a feed, and away I’d go, about half an hour late.”

Benna: “She was good to Gertie, and she was good to me. We used to get our milk from her, because we had no cows when we first shifted.

“I can remember when Pat was born, Dad and Trigger James were deep-cutting for Mr Bill Thomason. That land was a swamp and Mr Thomason got a tractor man to pull up all the silver pine [kahikatea]. Dad and Mr James split the wood and made fence posts. Dad was farm manager and we lived in the house on the hill. We had sheep and a house cow.”

Gertie: “I ran home from school the day Pat came home. In those days, they used to keep the mums and babies for 10 days before they would release them.”

Benna: “Pat was a cry-baby. He cried and cried. Mum would tell Gertie to get on the rocker with him to calm him down.

“We shifted to Waitui because Dad had a job offer with more money, 10 shillings a week, from his brother-in-law but it didn’t work out and he got day work from the farmers around us.”

Gertie: “We were there for about 10 years, because I finished school in Waitui, and so did Joe.”

The family may have moved to a smaller property, but the new locality held immense exploratory potential for the boys especially.

Benna: “Mum would always be yelling to me, ‘Benna, Skin’s fallen in the creek!’ He’d get Dad’s gumboots—up to his thighs—and go down the drain next to the creek, looking for duck eggs. The boys would fight for those duck eggs.”

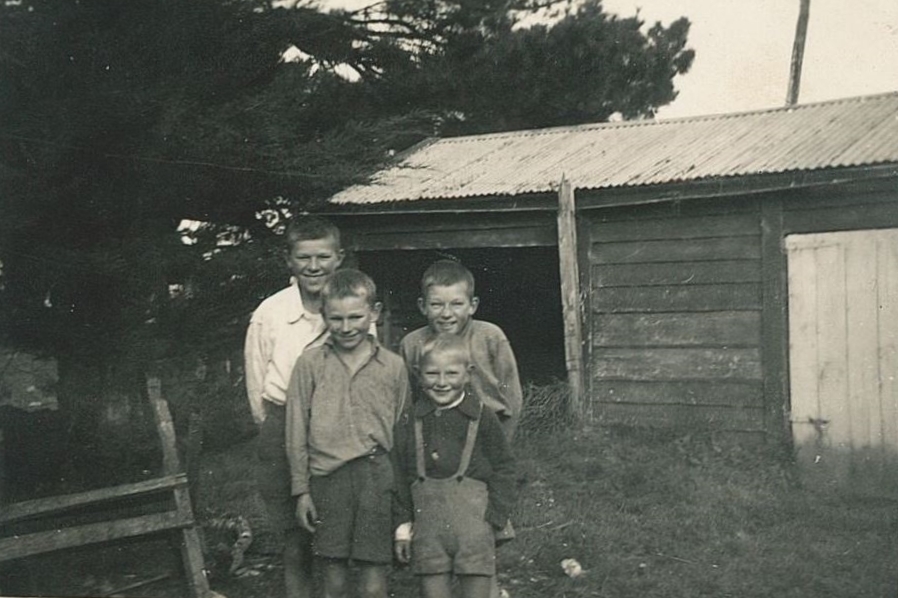

The younger Kuklinski siblings at the Waitui farm: Thomas is at the back, with Mick in front of him. Peter is behind the youngest, Patrick.

Patrick Kuklinski with the family dog, Towser, under the washing line that his mother resorted to tying Mick to. Benna: “He was always wandering off, even in town, and mum got so cross one day, she tied him to the line. Once was enough!”

Bernadette’s first paid job was working as a nanny for Irene and Jim Stachurski, who lived “across the fence” in Waitui. After two years, she cared for another neighbour, Ivy Sattler, and her children, until her husband died after misjudging a bend on the road home and crashing down a hill.

Benna: “Ivy was sick. I worked for her for about six months, and then she said, ‘I can’t afford to keep you, Benna, but I’ll see if I can get you a job. My sisters work at the Stratford hospital.’ I worked in the nurses’ dining room for about three years, then looked after Father McGlyn for about nine months, in the big house opposite [the Inglewood Catholic presbytery].”

Gertie: “We’d shifted into town by then.”

Benna: “Joe was working for our uncle Mick [Potroz] when Dad found this little well-rundown house, and we shifted to Inglewood.”

The family’s move to Inglewood coincided with Joe’s receiving his compulsory military training (CMT) for all 18-year-old males in New Zealand. By the time the 10-week course at Trentham finished, the family had settled into the house in James Street, an area known for its Polish families.

Joe Kuklinski, with his parents and brothers, dressed and ready to leave for military training. Sitting along the wall from the left is Ellen, Peter in front of Joe, Patrick, Jacob and Mick. Tom is in front.

Benna: “I still worked in Stratford, and Pauline was working in New Plymouth then, so when Joe got home, there were nine of us in that little house. It was the happiest place. There was a big lawn on the roadside, in front of the house, and they played cricket all the time.”

Gertie: “The boys from the neighbourhood all played rugby, the girls would gather around here and we’d go down and watch them, and Mum would cook enough tea for everybody. The more kids there were in the house, the better Mum liked it.

“Mr Fabish said to Dad one day, ‘Your house is condemned. It’s not really fit for a family. If you can get enough money to buy the section from the lady who owned it—Mary Butler of Tariki—I know a builder who will build you a new place.’ I think it was a hundred and something pounds, not very much. Dad and Mum went to the lawyer and got a 30-year government loan.

“It was Bernard Fabish. He was marvellous like that.”

Benna: “He lived on the corner, up the road. It was about six months before we started to build. They had to take off the back part of the house, and the washhouse. Everything had to come off, and we had to live in the sitting room and the three bedrooms. They built in the veranda, and the two boys slept there. All the boys helped put in the concrete paths.”

Gertie: “It was lucky, because it was summertime. We all fitted in. We were happy.”

Jacob, left, with his half-brother, Frank Dravitski, outside the Kuklinski’s first Inglewood house. Frank, named after his father, was seven when he died in December 1886.

Mary (née Dravitski) Biesek joins her brother, Frank, and half-brother, Jacob Kuklinski, at a formal function. Mary was eight months old when her father died. She married Paul Biesek in 1906.

Pat: “There was always cricket on the front lawn. We only broke one window in the new house, which was amazing. If you hit the ball over the fence, you were out.

“I caught up with Bev Maxwell the other day. She lived in Elliot Street, the next road down, and she said that she was always too frightened to come past our place because we were all out there playing cricket. She walked the long way around.”

Peter and Tom paid Pat “two bob or half a crown” to clean their rugby boots and laces in season. Independent Joe played hockey. Ellen Kuklinski, mother of five energetic sons, used to make an embrocation of methylated spirits, egg whites and milk for them to rub on bruises.

Pat: “We used to have some beauties.”

Joe: “We used to rub it on, and you’d feel the tingle in your legs.”

Pat: “It used to bring out the bruise, so if you got it on a Saturday, by the following Saturday you were ready to play again.”

Joe: “In those days, they made what they could. She got the recipe from the old people.”

_______________

When Joe returned from his CMT, he apprenticed to the local panel-beater, Sandy Slater, a member of the Inglewood Volunteer Fire Brigade, who suggested he join.

Joe found his element. The medals accumulated, and in 2002, he received the Queen’s Service Medal for 50 years’ service to the Inglewood Fire Department.

Joe: “When the siren went, we answered it.”

Patsy: “Most of the panel-beaters were in the Fire Brigade, so when the siren went, the dog was first on the ute, then the men, the ute disappeared, and too bad if you wanted your car fixed that day. Businesses didn’t mind in those days. These days, the ones that release their [volunteer fire] staff are a minority.”

Haystack and chimney fires prompted most of Joe’s early calls, about 50 a year at first, but as Inglewood grew and the roads became busier, car crashes increased, and the job evolved to include “getting people out of cars.”

_______________

Benna: “One day, I went to an Inglewood school picnic with mum and I said I’d like to go to Napier, to work. Mum didn’t want me to go, then we met Mrs Rose, and she said, ‘Benna, why don’t you go to work for Fun Ho! here in town?’

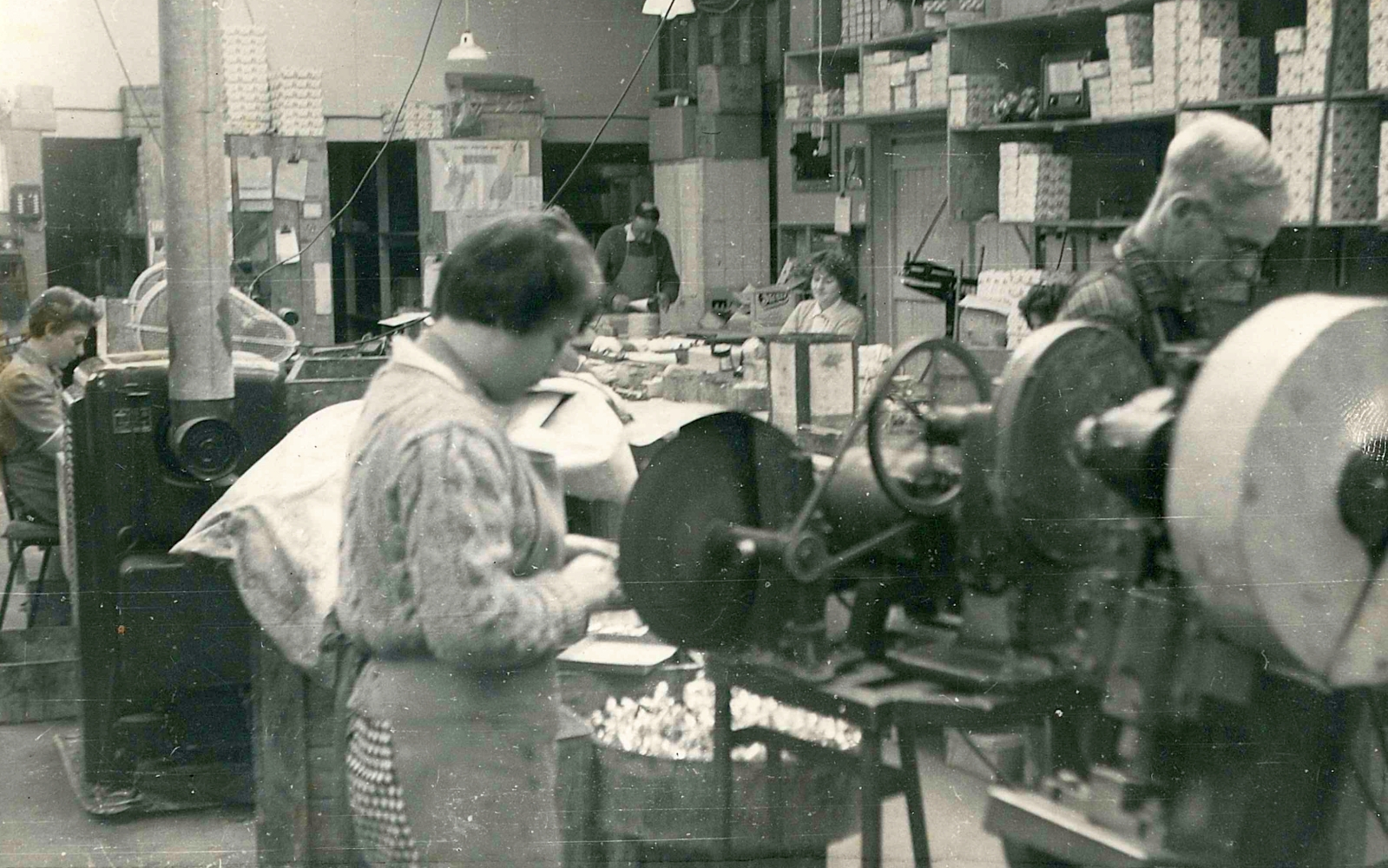

“It was the toy factory, in those days in full production. It became Underwood Engineering later on, and I worked there for 33 years. I painted toys, painted hats on tractors, whatever needed doing, and then I went into the packing department. Now they’re out of production, it’s a museum in the town centre.”6

The factory floor at Fun Ho! toy factory in Inglewood.

The Kuklinskis had not lived in Inglewood for long when a neighbour told Gertie about a job at a local garment factory, Zembas, which produced mainly pyjamas.7

Gertie: “She took me in to see them, they gave me a job, and that was it. I’d never sewed before, and I became a machinist, and that’s where I stayed for 35 years, until they built a new place in New Plymouth and closed this one down.”

Benna: “She became foreman, but when they gave her a job in New Plymouth, she had an allergy to their moth balls, and came home.”

Gertie: “We stayed home, and we got used to it. We had Mick with us. He didn’t marry either.”

Benna: “He worked at the dry cleaners and then in the bakehouse, but the flour got on his chest, and he got himself a job at Taumarunui King County Electricity, the power lines. He worked there for 14 years, and then he came home and worked here for the Taranaki Power Board in those days; then it became Powerco, then Tenex, and now they’ve gone back to calling themselves Powerco.

“Mick retired in the April and died 10 months later, of cancer, on 8 January 2007.

“Tom was a butcher from the start. He left school and learnt the trade from Bob Lamplough, the butcher in Inglewood. He married Mary Horgan, and lives in Auckland. He worked for the Mad Butcher in Mangare until he retired.

“Peter worked as a toll operator supervisor at the post office exchange in Inglewood. After he married Robin Mumby, they moved to Hawera, and he worked on the exchange until it closed. After that, he had jobs around the racecourse and stables in Hawera, and then worked at the golf course until he retired.

“Pat got into the grocery business. After he married, he bought a shop in Palmerston North, and then moved to Waikanae. He’s only been back in Inglewood for 13 to 14 years.”

_______________

The sisters have never regretted not marrying, nor having their own families. Being sandwiched between older Joe and four younger brothers gave Gertie an affinity with the five boys.

Benna: “If the boys were in trouble, they’d go to Gertie.”

Gertie: “We really did get on good. I had plenty of girls to play with, because there were girls around where we lived in Inglewood, but we had so many brothers, and we had to do a lot of their work, and I used to think, ‘Bugger ya! I don’t want to be doing that the rest of my life.’”

Benna: “Already, every Saturday afternoon, we used to go to the priests’ house and do their housework.

“On a Saturday morning, I’d be busy cooking, and I’d make a sponge or biscuits. The boys would come home, and when I’d look at my cake again, there’d be a piece cut off, or biscuits would be missing. Tom was the worst!

“I’ve always been the one who had to do the cooking. Pauline was never at home that much.

“Pauline’s first job was in a fish shop in New Plymouth. She worked as a housekeeper in Christchurch for about five years then came home and went back to New Plymouth, where she met her husband, Campbell Fraser, known as Cam.”

Gertie: “Mum didn’t really cook. Dad had to teach her when they got married. She was pleased that Benna was interested and wanted to cook, and told her, ‘Go ahead.’”

Ellen, the ninth of Thomas and Mary Potroz’s children, and her sisters, Millie, number 10, and Pat, number 11, had no need to learn to cook. Instead, Ellen became comfortable in the company of her siblings and loved reading, which her illiterate mother encouraged.

Benna: “My mum wasn’t a cook, but used to read books to granny Potroz, who only knew Polish. Before Mum married, she and granny would be up to three o’clock in the morning reading books.”

The youngest daughters of Thomas and Mary Potroz: Ellen is standing between her younger sisters, on the left, Teresa Teckler (Pat), and Amelia Rose (Millie).

When the local newspaper interviewed Ellen and Jacob about their 50th wedding anniversary in 1979, they shared the snippet that for 70 years they had never lived more than a “mile-and-a-half” away from each other. As children they had lived “within walking distance” on farms in Kaimata and, although they went to different schools, visited regularly.

Jacob and Ellen Kuklinski at their 50th wedding anniversary celebration in 1979.

On the same day, Ellen and Jacob Kuklinski surrounded by their children and grandchildren, outside the Sacred Heart Catholic Church in Inglewood.

Jacob’s first job in Inglewood had been a three-month stint at the Fun Ho! factory. After a short time with the local concrete works, he found full-time employment alongside Joe at SJ Slater, preparing cars for painting until he retired at 70.

Ellen told the reporter she “would love to go back to the farm tomorrow.”

Joe: “Dad was a quiet man.”

Pat: “He was quietly spoken. When he said something, we all stopped. You’d only have to hear, ‘That’s enough,’ and that was enough. I only ever got one hiding, and deserved it. It was me and Skin—we were always together—chasing sheep around in the pen. We heard him bellow from way out in the paddock somewhere, and I thought, ‘Here we go.’ I was crying before we got home, but that didn’t work. I must have been about five.

“Mum was the peacemaker.”

Joe: “We used to play cards against her, and aunty Millie, Euchre.”

Pat: “I remember one incident. It was a Sunday night and aunty Millie was there, and Joe. I think Corky [Ian Corkhill] might have been playing, and Skin might have been the other one. And aunty Millie would say, ‘Oooh, Ellen, I’ve got a sore heart. I’ve got a pain in the heart.’ Or, if she had spades in her hand, ‘Oh, you’re digging spuds, Ellen?’ I was standing next to Mum when she dealt the cards out and turned up the Jack of Diamonds. She picked it up, and said, ‘Hearts and alone.’ She had all the big ones, and not one of them said a word. I got the look, and knew not to say anything.”

Benna: “Mum loved the farm. She loved those cows. She would stand at the kitchen window and watch them come down the hill to be milked, and she loved the garden. When Dad retired, he mowed the church lawns and did whatever jobs the priest wanted him to do. Mum just carried on.”

“Mum always used to dig the garden. She planted vegetables, and always had flowers. She had the kids planting out the spuds.”

Pat: “The only time I remember Mum killing anything was a chook here in Inglewood. I had to hold the chook, and she cut off the head. Woosh! The blood was everywhere and I let it go. Mum yelled, ‘Catch it!’ but I wasn’t going anywhere near it. In the end, it stopped running around, and that was tea for the night. It was quick for the chook, but poor Mum.”

Joe: “With Dad, you had to be on time, every time, if you were going somewhere. If you weren’t on time, you were left behind. Not that it taught my elder sister!” [Benna]

Patsy: “Joe was the same with his own kids. If they weren’t ready, he said, ‘You stay at home.’ They never did it again.”

As their parents got older, Bernadette biked home every day at lunchtime to check on them.

Benna: “Then Dad got sick, and somebody had to stay home and look after him. Dad was already 90, and I looked after him for 10 weeks until he died.

“Dad always celebrated his birthday on Anzac Day. Mum always bought him a cow heart for tea, and that was our meal. It was quite tough; you had to know how to cook it. She boiled it, stuffed it, and roasted it in the oven.

“People came to wish him a happy birthday and stayed for tea. Mum would say, ‘It’s only cow heart,’ but they would say they didn’t mind.

“Dad celebrated his 91st birthday on Anzac Day 1984, and died two days later.

“I carried on looking after Mum, because she wasn’t very well herself after she had a stroke. She died five years later, when she was 84. I was turning 60, and able to get the pension, and it felt right to retire. The garden took all of my time.”

The Kuklinski siblings together at what Benna remembers was probably the wedding of a nephew or niece. From left: Pat, Mick, Gertie, Peter, Pauline, Tom, Benna and Joe. Benna had broken her arm after falling off a ladder.

At 87, Joe remains custodian of the Inglewood Fire Station. He opens the station every morning, raises the New Zealand flag, and does odd jobs like mowing the lawn and putting out the rubbish bins.

Joe: “It’s good, because I can meet all the new ones who join.”

Joseph Martin Kuklinski, as Chief Fire Officer at the Inglewood Volunteer Fire Brigade, poses with his wife, Patsy, for the official photograph taken after Dame Silvia Cartwright presented Joe with the Queen’s Service Medal for Public Services, at Government House in 2002.

Joe’s life membership jacket of the Inglewood Volunteer Fire Services is heavy with his service awards. To the right of his QSM is his CMT New Zealand Defence medal. Below, from left is his New Zealand Fire Brigade medal for Long Service and Good Conduct, the 2001 Volunteer of the Year medal from the New Zealand Fire Service, his 50-year Long Service medal from the New Zealand Fire Services, and his honorary life membership medal from the United Fire Brigades, presented to him in February 1977.

Both of Joe’s sons followed him into the fire service, and both have received their 25-year Gold Stars, Richard in Inglewood in 2016 and David in Hawera in 2015. Richard’s wife, Nicola, has 12 years’ service and David’s son, Martin, has volunteered with his father in Hawera for the last eight years.

Twelve and a half years separate Pat, youngest of the Kuklinski siblings, and Joe. Pat’s earliest memory of Joe is his brother putting him on his bike’s handle-bars and giving him a ride. “You’d just come back from uncle Mick’s, I think.”

There is no doubt that when the Kuklinski family moved into Inglewood nearly 70 years ago, they brought with them the lively warmth and zest of their close-knit family. They became part of Inglewood, and Inglewood became part of them. The sisters still live in the renovated family home that replaced the ramshackle building their father found. Joe and Pat live nearby, in streets on either side of their sisters’.

Pat: “Joe would need to get a passport to leave Inglewood.”

A sentiment echoed by Benna and Gertie.

Gertie and Benna Kulkinski, outside their home in Inglewood, Taranaki, in 2018.

The sisters have a companionable, symbiotic relationship (Benna: “Gertie can’t see, and I can’t hear.”) and they are not short of visitors, including Joe and Pat, who pop in regularly with their wives (Patrick also married a Patsy, Patsy Herlihy).

Gertie: “My life has just gone along like that. I’ve enjoyed it all.”

Benna: “It was a great time. It was good, and it still is good. We get along together and the boys come and go.”

© Barbara Scrivens, 2019.

Updated June 2020.

THANKS TO THE TAKAPUNA BRANCH OF AUCKLAND LIBRARIES FOR THE LOAN OF AUDIO RECORDING EQUIPMENT.

ALL PHOTOGRAPHS, APART FROM THE LAST THREE, FROM THE KUKLINSKI FAMILY COLLECTION.

ENDNOTES:

- 1 - A Return of the Freeholders of New Zealand, giving the Names, Addresses, and Occupations of Owners of Land Together with the Area and Value in Counties, and the Value in Boroughs and Town Districts, October 1882, lists landowners Kuklinski on page 31 of the K-section, and Dravitski on page 42 of the D-section.

- 2 - Fabisz became Fabich, and Fabish in New Zealand.

- 3 - The New Zealand Government’s Te Tari Taiwhenua/Internal Affairs Births, Deaths and Marriages index spelt their names Jacob Kuklenski and Mariana Drewski.

- 54 - Thomas Bilski was born in 1910, the youngest of five children listed in the BDM, of Joanna (Jane) and Valentine Bilski. Joanna died on 6 June 1912.

- 5 - Ellen's sister Mary Anne Potroz married Joseph Biesek in 1918.

- 6 - The Fun Ho! Toys museum is at 25 Rata Street, Inglewood. The company lost business after the lifting of

trade sanctions in the late 1970s.

https://www.funhotoys.co.nz/Fun-Ho-History/Home.aspx - 7 - According to Te Moa, 100 Years History of Inglewood 1875–1975, in 1975, the factory produced 450 dozen pairs of pyjamas a week, mostly for Woolworths Ltd, as well as contracts for hospitals and the army, and gym shorts for the Air Force.

If you would like to comment on this, or any other story, please email editor@polishhistorynewzealand.org.