The Luskie Family

When Kenneth Luskie read Madeline Orlowski Anderson’s story on this website he knew he could fill some of the gaps left by a missing son, Madeline’s paternal uncle Bernard, Kenneth’s grandfather.

Kenneth and I met in February. He and his wife, Sue, were in New Zealand for a family wedding, and visiting his widowed sister-in-law, Pat Luskie, in Howick, Auckland.

Ken put me in touch with three more of Bernard’s grandchildren, his cousins Douglas and Ewen Luskie and Shelley Casserly.

This is the story of a branch of a large family but that branch did not grow alone, which is why I have included some ancillary ancestral characters. Like all families, this one contains different personalities, outlooks on life and coping mechanisms, people joined sometimes by just a name, sometimes by so much more.

Thank you to all who contributed.

—Barbara Scrivens

SOMETHING HAPPENED, SOMETHING SAID

by Barbara Scrivens

A fact, says my collins concise english dictionary, is something that has actually happened or is true, reality, something said to have occurred or said to be true.

That definition underscores the possibility of a difference between something that actually happened, which after an event only those present can confirm, and the something said, which can create its own reality.

Mark Twain is supposed to have said, “Never let the truth stand in the way of a good story.” But did he? Perhaps he appropriated an old proverb to add the twist also attributed to him, “… unless you cannot think of anything better.” Perhaps the twist was not Twain’s either. Only Twain would have known.

Good storytellers often embellish. Some stories, especially those handed down from one generation to another in large families, invite speculation—like why a son changed his name, surname and religion and apparently turned his back on his family.

Based on the few facts they knew, descendants of the Orlowski (originally Orłowski) family in New Zealand created their own scenario for the disappearance of Bernard Orlowski in the late 1800s.

Bernard was born in 1882, the seventh child and fourth son of August and Franciska Orlowski, who had arrived in Otago 10 earlier.

According to the ship’s passenger list, August, Franciska (née Anis/Annis) and their two children, Franz (2) and Maria (one month) boarded the palmerston with August’s younger brother, Johann (John Orlowski), Johann's wife, Anna (née Maślak/Masiewski) and their daughter, another Maria (18 months). There is no record of Franz in New Zealand so one may assume he was among the 10 infants who had died during the voyage from pneumonia or dysentery.1

August and Franciska made Waihola their home and had another nine children there: Anna, Martha, August, John Andrew, Bernard, James, Thomas, Michael and Frances. August senior became a successful builder and farmer and made it clear to his children that his oldest living son, August junior, would inherit his farm.

Did August decide to give his farm to one son because he did not want to dilute his legacy? Keeping the farm as a whole may have seemed logical to a man with five sons and five daughters.

The family story is that August senior taught August junior his legendary carpentry skills, his next son, John Andrew, less and Bernard, little.

August senior and Bernard did spend time together on the farm. One day, the two were cutting down pine saplings when August apparently warned Bernard to take more care. The family story is that when Bernard accidentally cut off two fingers from his left hand, August laughed, annoying Bernard to such an extent that he left home, and changed his name, surname and religion.

Bernard did leave home but not immediately after the accident, according to one of his grandsons, Douglas Luskie. Neither did Bernard leave of his own accord: His father sent him to Mosgiel to enter the priesthood.

Sue: “We’d heard the lumberjack story several times but not that his father sent him off to become a priest. It made sense, because the Poles were very Catholic, but the reason behind the name change was nothing like what we were told.”

Bernard did not get off the train in Mosgiel but carried on to Dunedin and found a job driving a horse and cart for W Casey and Sons. The cartage contractors based at 1 Wickliffe Street had secured a contract with Milton Lime and Cement to make cement from clay in the harbour and lime from Milton.

The year that Bernard by-passed Mosgiel on the train is unclear but James Casey started his business in 1888 and by 1900 supplied numerous building sites in the prospering city. For Bernard, a strong tall young man used to horses, who understood his status in the family hierarchy, it would have been an ideal way to explore Dunedin, indulge his rebellion and contemplate his own future.

Douglas: “He did the horse driving for quite a while, then applied for a job on the tramways. When my grandfather told the man in the pay office his surname, the man said, ‘Too difficult, we’ll call you Luskie.’”

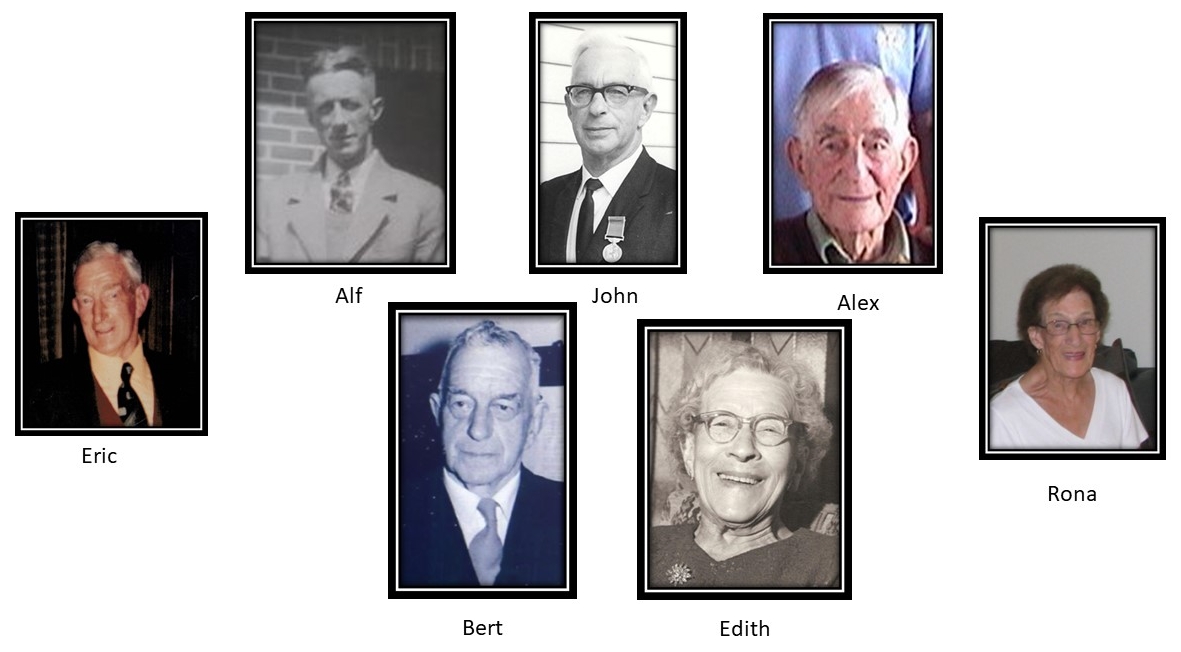

Herbert (Bernard) Luskie, middle, with two other Dunedin City Council Trams employees during the mid-1920s or early 1930s. Herbert told his family he felt lucky to be employed during the Great Depression.

And so Bernard Orlowski became Herbert (Bert) Luskie, the name with which he married Edith Charlotte Wates in 1905. On his marriage certificate he gave his father’s name as August Luskie, carpenter, and his mother as Franciska Luskie, née Annis.

That marriage certificate effectively cut Herbert and his descendants from the Orlowski name, although he did keep a channel open through supplying his mother’s maiden name. It is not clear why Bernard became Herbert but the latter may have suited him, as Bert had been his nickname in Waihola.

The first address the family has for Herbert is central Dunedin’s Lees Street but there is no obvious record. This, too, may have been mis-heard as his mother-in-law’s maiden name was Lees and W Casey and Sons operated from premises near Leith Street.

Herbert first appeared in stone’s otago and southland directory in 1910, which listed him as a labourer living in North East Valley.2

Herbert Luskie with one of the machines at Dunedin City’s tramways, probably in the 1940s.

Herbert and Edith had five children: Eric Herbert, born on 25 March 1906; Alfred Norman, born on 24 July 1907; John Wates (Jack), born on 5 December 1910; Wilfred Alexander (Alex), born on 29 October 1913 and Rona Isabel, born on 9 December 1917.

The personal and social column in the otago daily times featured Alfred’s December 1932 wedding and described Rona, one of three bridesmaids:3

… Miss Rona Luskie, wearing a dainty frock of pink and blue floral georgette, fully flared, the tight-fitting bodice being finished with a coatee to match and a blue crinoline hat trimmed with an upturned brim, and carrying a bouquet of pink sweet peas…

_______________

Wilfred Alexander Luskie and Margaret Alice Campbell on their wedding day in February 1935.

Alex and Margaret at a function years later.

Ken, Alexander’s son, was born in Ashburton in 1945, 10 years after his sister, Alma Edith, and seven years after his brother, Raymond Alexander. Ken remembers his grandfather “not liking grandchildren… Perhaps it was the Polish thing, but I don’t recall him ever speaking to me.”

Alexander may not have been as brusque towards Ken as Herbert but was almost as distant.

“Growing up on the farm, I saw very little of my dad. He was gone before dawn and back after dark and there was not a lot of interaction between us.”

Pat: “Ray did a lot with him because he was that much older. He got out with the horses and did quite a bit on the farm. Whether he was helpful, who knows? I know he loved being out there with his dad.”

The only explanation Ken and Pat can find for Alexander’s moving his family from Dunedin city, where Alma and Raymond were born, to the farm in Mayfield was that free-spirited Alexander needed change.

Ken Luskie, left aged about six, grew up on the farm at Mayfield, north-west of Ashburton. The family later moved to a farm in Waituna, inland from Waimate, but injuries and heavy farm work took their toll on Alexander and the family moved to Christchurch around 1956.

Ken: “Aunty Rona told me that he loved motor bikes. These days you’d call him a ‘bikie.’”

Before farming, Alexander worked as a presser and sewing-machine mechanic for Sargood, Son & Ewen’s in Dunedin. He had been indentured as a clothing cutter and made suits. Pat remembered her father-in-law was “very good at sewing and knitting.”

The Herbert Luskie-Edith Wates marriage certificate showed Edith as a dressmaker.4 Jack used to help his mother cut out patterns and there is no reason to doubt that Alexander, three years younger, did not also absorb the process and his mother’s technical ease.

His farming caused Alexander to miss his World War 2 call-up.

Pat: “Farm workers were needed on the home front to supply the food. From the way he spoke, I think he regretted that. He would have liked to have done his bit…”

Sue: “Particularly when both his boys joined the Navy.”

In 1960 Pat (née Sorrell) lived in Portsmouth. Raymond Luskie was among those commissioned to collect the otago for the New Zealand Navy.

Pat: “It was a brand new frigate. We met and married quite quickly. I was 18 and he was 21. He came back to New Zealand on the ship and I got sent out earlier and met the Luskie family at the airport.”

Pat left behind her parents and three sisters.

“I never gave leaving them a thought. When I think back, I know I broke my mother’s heart, I know I did, but it was all right afterwards. She came out to New Zealand numerous times.

“It was hard for me. The marriage should never have lasted because we were so young. We had no money and nowhere to live… but we toughed it out.”

His brother’s glamorous Navy career attracted Ken, who enlisted in November 1961 as a junior mechanical engineer.

“My view of the Navy when I signed up was: You get a smart uniform, went on a ship, sailed to exotic foreign ports, had a good time and you came home again. I didn’t give any thought to what you did between getting on the ship and getting to the foreign port, working all those hours and in those conditions.”

Ken remained with the Navy for 10 years and left as a Petty Officer Mechanical Engineer. He joined the New Zealand Police in 1974 and served in Nelson and Auckland before moving to Brisbane in 1980.

Alexander and Margaret Luskie with their children, from left, Kenneth, Raymond and Alma.

_______________

As a child, Ken met only one other member of the Orlowski family—Minnie.

“I was very young. Mum and dad took me with them to visit her and I thought, ‘Why would someone be called Minnie? What a strange name,’ but she spoke Polish.”

Minnie was John and Anna Orlowski’s fifth child, and Herbert’s cousin, born a year after him.

_______________

In the 1870s the brothers August and John (Johann) Orlowski sparked the migration to New Zealand of their entire immediate family. Their parents, Joseph Alexander and Bridget (née Parobkiewicz) Orlowski had their seven children within seven kilometres of where they married in Miłobądz in Prussian-partitioned north-west Poland. August was their second child and oldest son and John their fourth child and second son.

Three of their siblings had died before the brothers boarded the palmerston, a brother and sister as infants and an eight-year-old sister in 1857.

August and John left behind their parents, older sister Anna Maria, by then married to Michał Wiśniewski, and a 20-year-old younger brother, Joseph junior. Anna and Michał, who had seen five of their eight children die as babies, arrived via the reichstag in 1874 with August (12), Antoni (3) and nine-month-old Bernard.

In 1875 the friedeburg, which berthed in Napier, recorded among its passengers a J and Catharine [sic] Orlowski, aged 62 and 55. Joseph’s mother was apparently named Catharine. This misunderstanding between his mother’s and his wife’s names suggests that Joseph and Bridget Orlowski travelled alone and had no one to interpret for them.

The New Zealand colonial government’s termination of assisted immigration from continental Europe in 1876 (see the story the fritz reuter) did not deter the last of Joseph and Bridget’s children from joining his parents and siblings in New Zealand. Joseph junior sailed from Glasgow on the oamaru on 24 October 1877, bound for “Otago and The Bluff,” and arrived in Port Chalmers on 18 January 1878.

Joseph junior fudged his true nationality. The ship’s passenger list recorded him as a labourer from Middlesex, one of four ‘Englishmen.’ The ship carried mostly Irish and Scottish people and one Welshman. Like most of the other adult men, Joseph junior paid ₤13 11s 6d for his passage.

He settled in Waihola and married Pauline Philipowski, who had been scheduled to travel to New Zealand on the fritz reuter with her parents, Johann and Rosalia, and at least one sibling, Joseph (5). Instead, she sailed alone, aged 16, and arrived in Napier on 18 March 1875.

One explanation for Pauline’s parents not embarking on the fritz reuter was that a baby sister, Bertha, had died in or on the way to the Hamburg. Or one of the other three may have taken ill, and Pauline’s parents wanted to make sure she escaped Prussian rule in Poland. There is no apparent familial link between the Philipowski family and others on the fritz reuter but several links to Rosalia’s maiden name, Grabowska, among Polish settlers already in New Zealand.

Two days before Pauline reached Napier, her parents and brother left London aboard the earl of zetland bound for Otago. The ship’s summary shows that they were the only non-British passengers.

_______________

Some Poles aboard the palmerston in 1872 apparently thought that they were destined for America. An easy mistake considering two facts: many immigrant ships from Hamburg were destined for America, and German immigration agents wanting to reach their quotas and retain their commissions had reason to avoid the truth.

A repeated story is that even after they arrived in New Zealand, some of the Poles wrote “Amerika” on their birth and marriage certificates. Without proof, this is an unlikely scenario. Why would officials taking records in New Zealand accept the unmistakable word America? Even those who were initially under the impression they were joining relatives in America must have doubted a trip across the Atlantic would take more than four months.

The palmerston passenger list classified all the men as farm labourers or labourers. This is what the New Zealand government’s assisted immigration scheme called for and what the immigration agents provided but it stretches the bounds of coincidence that not one man on the ship had a listed profession. August, for instance, was a carpenter.

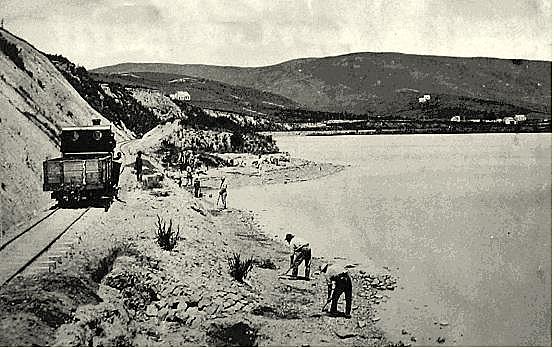

Colonial farmers in New Zealand were slow to employ non-English speakers with large families and many of the palmerston Poles accepted jobs to extend the railway line through the Taieri Plain south of Dunedin.

Working together strengthened the Polish community in a way that would not have happened had they been scattered among the isolated farms and absorbed by the predominant English-speaking farmers.

The most common job building the new railway—platelaying—involved lifting the heavy sleepers and rails to assemble the physical lines. Others dug out cuttings to drain swampy land, built bridges and embankments, built railway stations and surveyed the route of the proposed lines. Specialist engineering trades managed explosives. Other employees were responsible for housing and feeding the construction staff and gangs.5

The Polish families lived in tents and eventually bought their own properties nearby.

Before the railway, inhabitants and visitors to the Waihola settlement arrived by boat up the Taieri and Waipori rivers and across Lake Waihola.6

By the time August Orlowski sent Bernard to Mosgiel, the railway had become the fastest and most popular mode of transport between Waihola and Dunedin.

A section of the new railroad alongside Lake Waihola.7

_______________

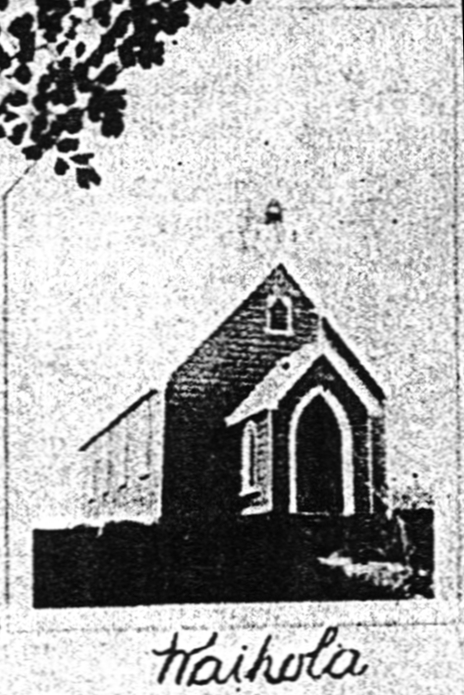

In 1898, the year before he died, Pauline Philipowski’s father, then known as John, gifted a section in Nore Street, Waihola, for the erection of a Catholic church.

By then August Orlowski had a reputation as a master carpenter. He helped designer-builder, a J Barty of Balclutha, to build the church and later continued to maintain and repair the building.

Left, the St Hyacinth Catholic Church in Waihola as it appeared on a local postcard.8 It opened officially on 16 April 1899. As new generations moved away from the area, the congregation diminished and in 1948 the Waihola Poles saw their church put on a barge and transported to Broad Bay on the Otago Peninsula.

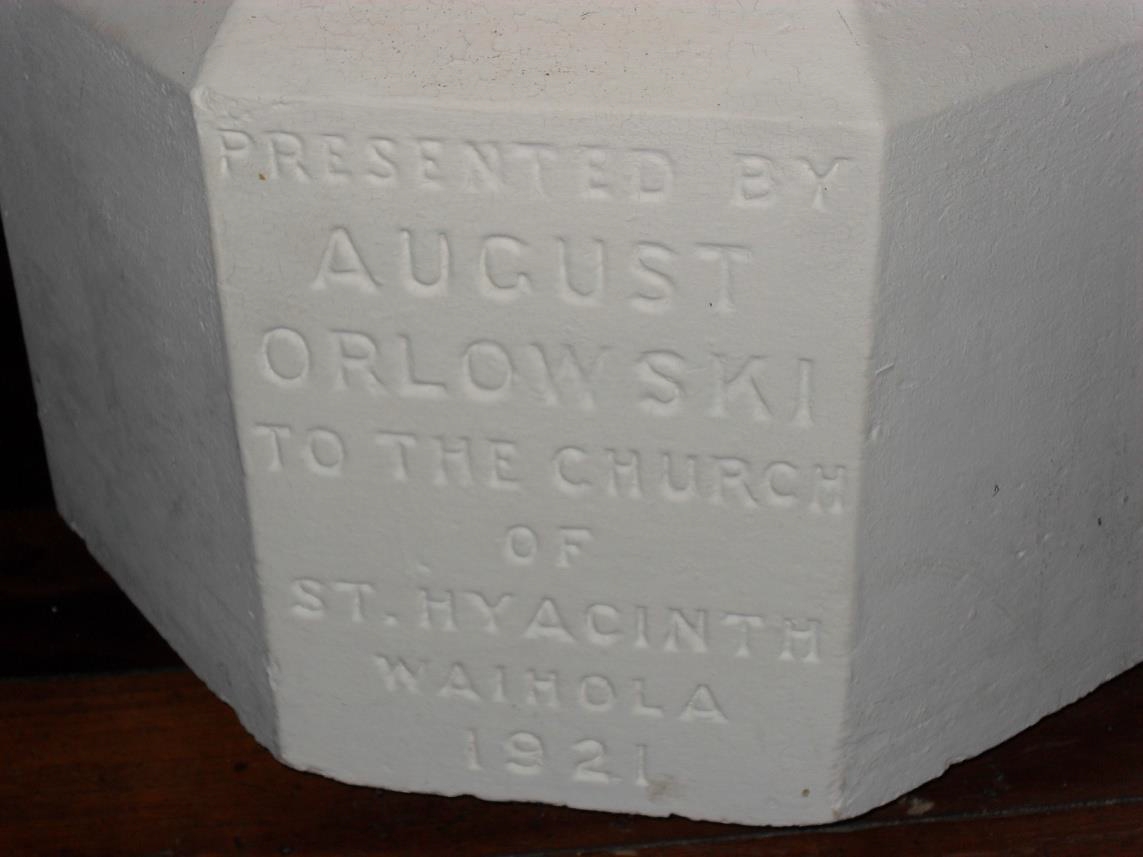

The baptismal front that August Orlowski junior gave to the church in 1921 followed the building to Broad Bay, which was renamed Mary Queen of Peace.

The mention of St Hyacinth in the font's inscription is the church’s only physical link to its original Waihola location.9

All 10 of August and Rosalia Orlowski’s children attended the Waihola School and transitioned between their Polish lives and their English community. Like his older brother, John Andrew (see the madeline orlowski anderson story), anyone speaking with Herbert without knowing his surname, would have passed him for a New Zealander.

_______________

Stone’s records that Herbert Luskie owned eight properties in Dunedin between 1910 and 1947.10

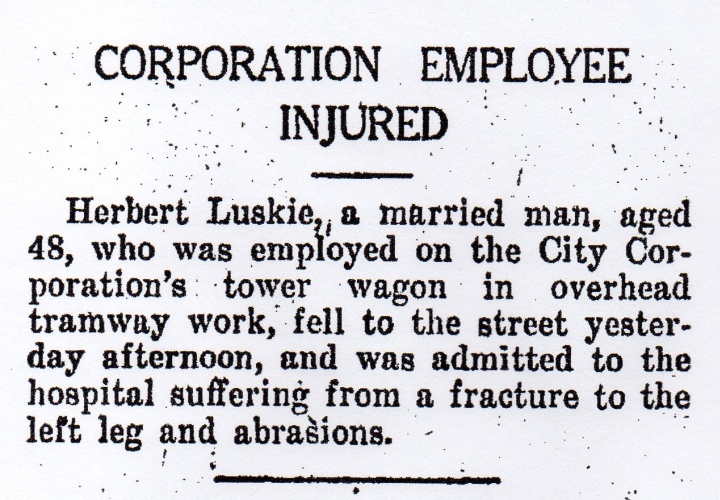

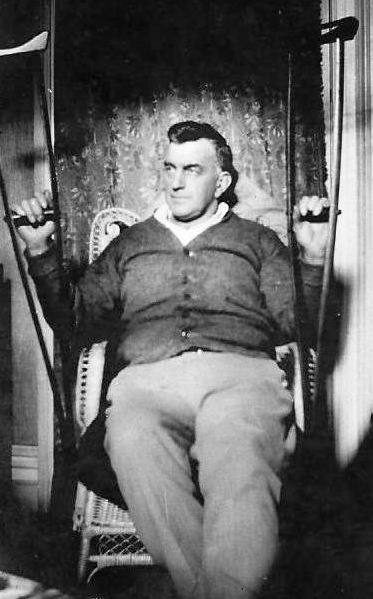

The otago daily times played down an accident he had on the tramways in August 1931.11

Herbert’s granddaughter Shelley Casserly recalls that a massive electric shock during the routine maintenance caused him to fall and he was lucky to survive.

Herbert bore sole responsibility for another broken leg a few years after the tramway accident. During one of his visits with Edith to their daughter, Rona, he misjudged his jump over a door propped up outside. His left hand shows only the tip of his middle finger missing.

Shelley spent many hours with Herbert and does not specifically remember his loss of fingers, so the story of the Waihola farm chopping accident may well have grown with the retelling.

Shelley does not remember Herbert constructing anything but knows he delighted in his garden.

“He was a great gardener and grew the best the best red currants, raspberries and blackberries that I ate straight off the plants in Craighall Crescent [Dunedin].”

Herbert and Edith with Rona’s daughters Shelley (left) and Kay in Dunedin in 1958. Kay died from a brain aneurysm on 26 December 1992, aged 39.

After Rona and Jack Crombie married in 1939, they managed a high country sheep station where Shelley was born and where they lived until she was five. She remembers one particular story epitomising her grandfather’s stubborn nature:

“It was winter and the last of the root vegetables were still in the ground… frozen ground but he was determined to get the last of the carrots out. After many fruitless attempts, he resorted to the blowtorch… He set fire to the hay bales that were the side walls of the garage!

“Bert loved his cricket and also played. Mum told the story of him coming down the road after a cricket match (and a few beers) in the rain, umbrella up and singing his heart out.”

Herbert and Edith on holiday in Timaru in 1934.

Shelley spent school holidays with Herbert and Edith in Dunedin until her father died when she was 12.

By then, the Crombies lived in the Lake Roxburgh Village that housed employees on the Roxburgh Hydro Dam project. They had followed Rona’s older brother, Jack (John). The two families lived across the road from each other.

Herbert and Edith with, from left, Albert, Rona and Jack Luskie.

After Jack Crombie died, Herbert and Edith moved to Alexandra where Rona built a house. Herbert died from a stroke on 20 June 1962, aged 79, and did not see it finished.

Eric Luskie briefly worked as a butter maker before following Herbert as a tram driver for the Dunedin City Council. Eric married Olga Tucker in 1924. They moved to the Catlins and settled in Owaka on the Catlins coast.

Ewen Luskie, their sixth son and youngest child, remembers the mills at Tawanui, Ratanui, Huipapa and Glenoamaru, which Eric left to join the Ministry of Works at the Roxburgh power project in 1951. Eric first worked in the transport division, then the carpenters’ shop, from where he transferred to the Otematata hydro scheme on north Otago’s Waitaki river. Eric worked as a machinist until he retired and moved with Olga to Hampden, south of Oamaru. Eric died in 1982 aged 76, two years after Olga.

Like his cousin Ken, Ewen remembered the grumpier side of their grandfather and the calmer disposition of his own father.

Alfred Luskie predeceased his parents in January 1957. He died, aged 48, while holidaying at the Crombies’ in Roxburgh with his only son, 11-year-old Brendan. Alfred is buried at Roxburgh cemetery.

Alfred Luskie. After his father’s death, Brendan, who lived with him after his parents’ divorce, was adopted by his mother’s second husband and took his surname, Proctor. Brendan then lost touch with his Luskie roots.

Ken Luskie, left, with his cousin Brendan Proctor in Queensland this September. The two had not seen each other for 63 years. Douglas Luskie emailed Ken to say that he had by chance “run into” their cousin Brendan and thought he went by the name Proctor. Ken investigated further, found a Brendan Proctor in the “deep south of New Zealand” and confirmed the whereabouts of his long-lost relative.

On 14 June 1969 the General Chancery of the Orders of Knighthood at St James’s Palace, London, announced that the Queen had awarded John Wates Luskie a British Empire Medal (Civil Division). Then Senior Engineer’s Assistant (Mechanical) for the New Zealand Electricity Department, Jack had supervised the mechanical installation of the Roxburgh and Benmore hydro-electric dams.

On leaving the King Edward Technical College in Dunedin, Jack had become a mechanical apprentice at John McGregor and Son Ltd. He later spent five years at the railways’ Hillside Engineering Workshops and joined the State Hydro Department in 1940.

These photographs of Jack Luskie and Kathleen Isobella Godfrey were taken before they married in 1934.

Jack and his family after receiving his BEM (British Empire Medal) at Government House, Wellington in 1969. From left, Douglas Luskie, Judith Sutherland (née Luskie), Jack and Kathleen Luskie.

Five years later Jack’s nephew, Warrant Officer First Class Henry Eric Luskie junior, received an MBE. The Queen acknowledged him on her Birthday Honours List for his work with the Royal New Zealand Army Ordnance Corps.

Eric junior spent most of his 28 years in the army as the South Island’s only bomb-disposal expert. It meant being permanently on call and ready to travel anywhere in the South Island. Mike Crean of the press wrote Eric junior’s obituary in March 2007 and spoke to his son, Bruce, who remembered one particular holiday when his father had to submit a detailed itinerary and report his whereabouts to a police station daily.12

Late one night a military policeman knocked on the front door: A fishing trawler had caught three 25-pound artillery shells and had pulled them up Banks Peninsula. Eric wrapped the shells in two mattresses and took them to the army’s West Melton shooting range for detonation.

Although most of the infrequent call-outs proved to be for harmless objects and practice bombs, Bruce remembered a trip his father made to Nelson. The daughter of a World War 2 soldier was worried about the two German stick grenades her father kept on his mantelpiece. He had smuggled them back to New Zealand and she had polished them weekly. Eric’s inspection proved they were well able to do damage and removed them.

_______________

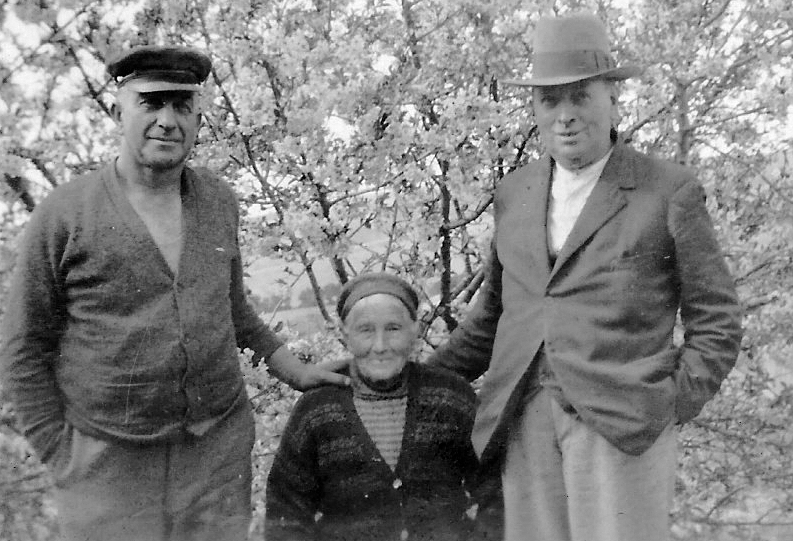

Whether Herbert ever completely mended the rift between himself and his parents is unclear but he did visit Waihola again as an adult, judging by these photographs taken with his mother and others.

These photographs taken of Franciska Orlowska surrounded with family were probably taken at the Orlowski farm in Waihola. Herbert is left in both. If anyone can identify the others, please let us know through our get in touch link.13

Herbert must have introduced Rona to her grandparents because he took her on a rowboat on Lake Waihola to catch eels that Edith smoked. After they became engaged and as newlyweds, Rona and John Crombie regularly visited August and Franciska in Waihola.

Shelley: “Mum played cards with Augustus and he always reminded her about the time she trumped his ace. The old folk would get my mum and dad to dance for them (they were great ballroom dancers) and Franciska also got my mum to do handstands for her.”

Herbert’s widow, Edith, died in Christchurch in October 1971.

Jack Luskie also died in Christchurch, on 24 January 1992. He is buried with his wife at the Waimairi Lawn Cemetery.

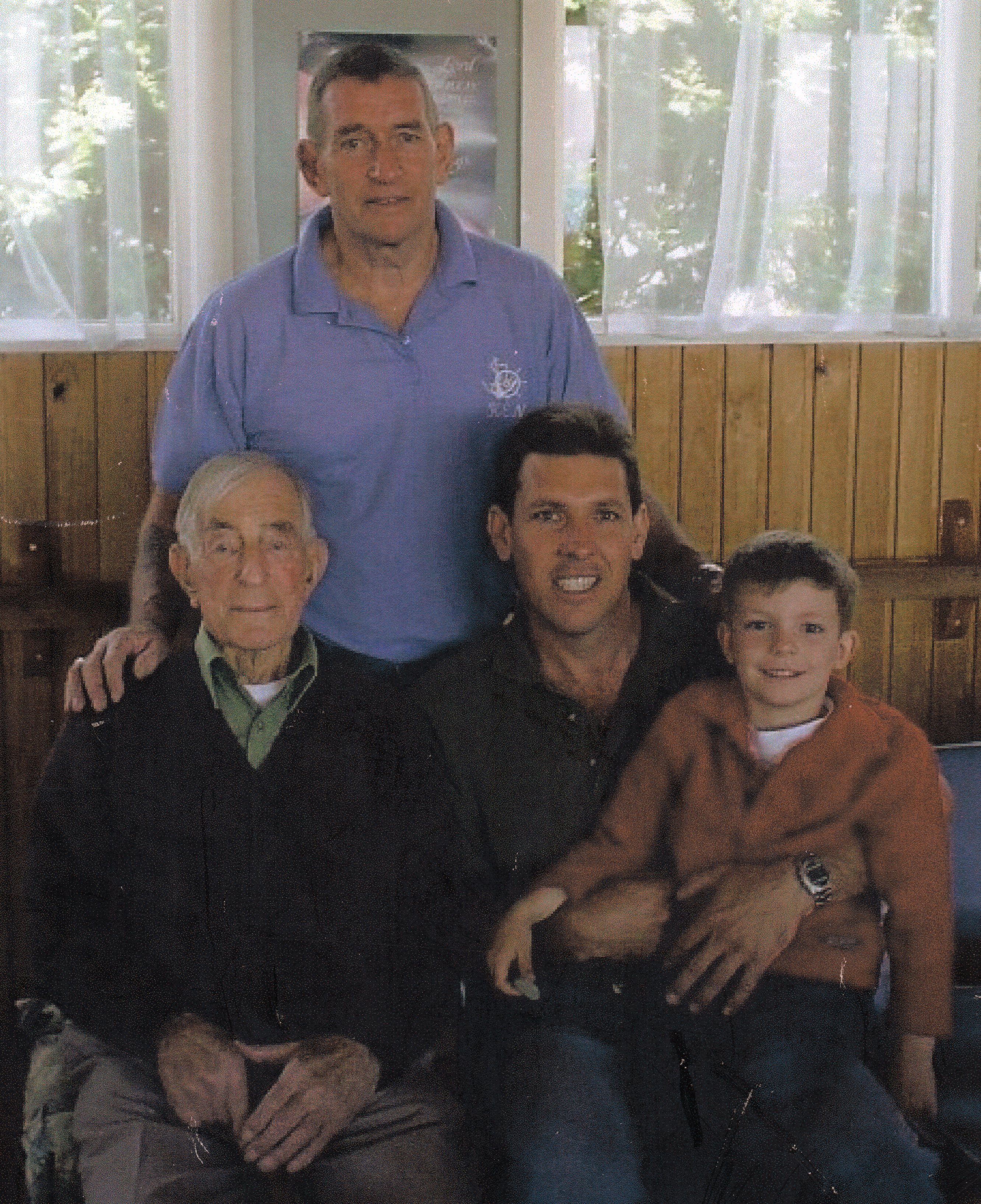

Alexander Luskie died in November 2003, the day after this photograph was taken at his 90th birthday celebrations. The four generations of Luskies include Alexander's grandson, Shane Kenneth, and great-grandson, Jake Alexander. Alexander senior's elder son, Raymond Alexander Luskie, died in Auckland on 14 January 2000.

Rona moved to Australia and died on 17 June 2012. Her ashes are buried with her daughter Kay on the Gold Coast.

Herbert Luskie’s plaque in the Alexandra cemetery reflects his life: no-nonsense and to the point. No storyteller, he took the reasons behind his complex character to his grave.14

© Barbara Scrivens, 2018

THANKS TO THE NORTH AUCKLAND RESEARCH CENTRE IN THE TAKAPUNA LIBRARY FOR THE LOAN OF AUDIO RECORDING EQUIPMENT.

APART FROM THE FIRST ONE, ALL PHOTOGRAPHS COME FROM KENNETH, DOUGLAS AND EWEN LUSKIE, SHELLEY CASSERLY AND HELEN SINCLAIR, CO-AUTHOR OF THE WAIHOLA HOSTORY PROJECT

ENDNOTES:

- 1 - Appendix to the Journals of the House of Representatives (AJHR), 1873 Session I, D-01, IMMIGRATION TO NEW ZEALAND. MEMORANDA TO THE AGENT-GENERAL, page 36, Enclosure no. 41.

- 2 - Information from the Archivist, Digital Services, Business Information Services, Dunedin City Council, http://www.dunedin.govt.nz

- 3 - Otago Daily Times, 16 December 1932, page 16, PERSONAL AND SOCIAL, Papers Past, through the National Library of New Zealand, https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/ODT19321216.2.121.1

- 4 - Marriage certificate shared by Shelley Casserly.

- 5 - Information from train enthusiast Michael Jarka.

- 6 - Information from Helen Sinclair, Waihola historian and co-author of the Waihola History Project.

- 7 - Photograph from Helen Sinclair.

- 8 - Ibid.

- 9 - Both photographs by Ken Luskie.

- 10 - Ibid, Digital Services, Dunedin City Council.

- 11 - Otago Daily Times, 7 August 1931, page 10, ACCIDENTS AND FATALITIES, Papers Past, through the National Library of New Zealand, https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/ODT19310807.2.99

- 12 - The Press, Saturday, March 31, 2007, page D19, South Island bomb-disposal expert.

- 13 - Top photograph from Ken Luskie; bottom photograph from Douglas Luskie.

- 14 - Photograph from Shelley Casserly.