A Nod to Old Warsaw

There is something about milestones in one’s life that put a perspective on what one considers important.

By 2009, although I had lived in three countries, on opposite hemispheres and sides of the world, I had never set foot in continental Europe. Five days in Poland to see maternal family were not enough then, and they made me yearn for more.

In August 2016 I marked my 60th birthday with three weeks in Poland, two on my own in Warsaw. As far as I know, my family has no connection with that city, but it drew me and I wanted to absorb its Polishness. No English-speaking husband. No children. No distractions besides the place.

I had booked an apartment on the edge of the Stare Miasto, the Old Town, on Podwale, overlooking the Barbican, part of its 16th century-defence wall. I love old architecture, and the address suited me.

I had to pick up the key, and caught a taxi from the airport to the office in Muranów. They gave me the key and address, and asked if they could call me a taxi to get to the apartment.

I decided I could walk the kilometre and a half. I needed to get my bearings, and wanted to investigate the grocery shops. How hard could it be rolling a suitcase and carrying hand luggage in midsummer, along unfamiliar streets? (If I had known about the cobbled pavements, I would have done my recce without the baggage.)

After a good hour, completely lost, I joined a crowd of tourists on Freta Street being told that the restaurant opposite was one of the most famous in the area. It had the best food, but the customers had to behave, or the owner would yell at them or throw them out. When the tourists moved on, I asked the speaker for directions: Podwale was around the corner.

The building used to be a convalescent hospital. The first evening started a ritual—I sat in the deep window-seat and watched the tourists go through the Barbican gates as the sounds of various violinists, choirs, and the regular clip-clopping of horse-drawn carriages drifted towards me.

Within an hour from seven the first morning, I had taken more than 60 photographs around the Stare Miasto’s market square. I kept thinking about a friend’s story of his trip to Poland in the 1980s. When researching a caption for it, I found out that residents who had survived WW2, came back not quite being able to pinpoint what was different—it had been rebuilt in the likeness of a Bernardo Bellotto painting rather than as it was before the Nazis bombed it.

The sub-standard post-war Soviet materials did not last, and there are huge differences between my 2016 photographs and his 1980s ones. Restoration continues. I loved the painted embroidery on the walls, the facade embellishments, and the intricate, quirky metalwork that sat on light fittings and shop signs.

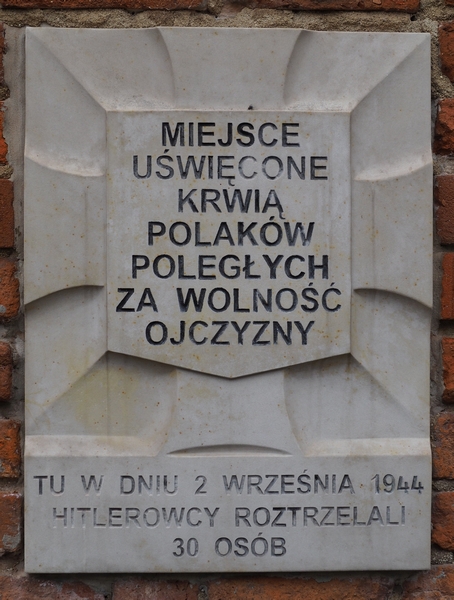

The first afternoon I turned right instead of left through the Barbican, noticed a plain cement plaque on a wall, and stopped short. On that spot the Nazis murdered 30 Poles—the same day my maternal grandfather, a bombardier in an anti-tank unit in the 1st Polish Armoured Division, was killed in action in northern France.

That was the first of many plaques and memorials I found and photograph as I walked around the Stare Miasto and beyond. Memorials of WW2 heroes touched me more than the overblown statues of kings or soldiers gone centuries ago.

I loved the way adults with children on their school holidays told them their history. As I waited to cross a street, I lingered to listen to a babcia telling her grandson about King Zygmunt on top of the huge column overlooking the Castle Square and beyond.

Sometimes, there were strange juxtapositions between the beautiful and the blunt. Barely 100 metres from an elegant statue of Marie Skłodoska Curie on the Kościelna, was this memorial to the AK, the Armia Krajowa, or resistance movement, active from 1942 to 1945. For 63 days from 1 August 1944, in what became known as the Warsaw Uprising, the AK held German troops back from the Stare Miasto and surrounds. As the photograph below says, we remember.

White eagles were everywhere, but I appreciated the bociany, the storks beloved by Poles like my late mother. I passed this one every time I went to get my pierogi at a recommended place on Bednarska. She seemed happy with her brood sitting on the roof of a bookshop on the Krakowskie Przedmieście.

The Varsovians’ serious appreciation of history, recent and centuries old, paralleled their sense of humour. An inn opposite the Royal Castle had this old man trying to make his getaway without paying.

I mastered the Metro—I had to, to get to a Polish friend who accompanied me to the National Library—but not the bus system. I feared getting on the wrong one. Not all my destinations were as far away as the Warsaw Uprising museum. My pocket-guide map told me, among many other things, that Marie Skłodowska Curie was born in the building housing her museum on Freta Street, a few minutes from Podwale.

I loved my time in Warsaw, and the last few days with my cousin Celina from Puck were special. I don’t know whether I would have been able to catch the train north if it had not been for her. When she said be ready to change platforms at any time, I knew that the protocols at the main Warsaw railway station were beyond me.

The last morning i n Warsaw, Celina insisted on popping around the corner for a quick bite at her favourite Warsaw takeaway. She led me to the very restaurant I had heard about on my first afternoon. The setting was stark, but the food was delicious.

What had I been doing walking to the pierogi place on Bednarska all this time?

—Barbara Scrivens

31 August 2021

_______________

Michael Jarka’s piece on 1980s Poland is available at: https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/visiting-poland-under-martial-law/

_______________

If you would like to comment on this post, or any other story, please email editor@polishhistorynewzealand.org/