Author: mum

They Lie Quietly

They lie quietly, many under names different from the Polish ones given to them at birth, and as far from the places they were born as it is possible to get.

Walk through almost any cemetery in New Zealand, and you will find someone of Polish heritage. More than 900 Poles who arrived in New Zealand between 1872 and 1876, as part of Sir Julius Vogel’s 1870 Immigration and Public Works Act, expanded within a generation to more than 3,000 scattered throughout the new colony.

Poles who disembarked from ships in Lyttelton and Port Chalmers tended to remain in Canterbury and Otago, but when the Fritz Reuter arrived in Wellington, its 511 men, women, children and babies were scattered in groups via steamers to settlements that were expected to grow with the new railway through the Manawatū, for example, and to bustling towns like Hokitika on the West Coast.

Of the 65 passengers met by boatmen in New Plymouth and rowed to shore, just 24 began what became the largest Polish community in New Zealand. Fifteen adults—one heavily pregnant—and nine children between 18 months and 13, left the Marsland Hill Immigration Barracks in New Plymouth on 6 September 1876, and started the walk to Inglewood, which had received its first settlers a year earlier and which was then still a clearing in dense bush below Mt Taranaki and accessed from New Plymouth by horse or foot.

The family names: Biesiek, Doduński, Duszyński, Myszewski, Neustrowski, Potroc, Uhlenberg, and Volzke, are easily recognisable in Inglewood, even with slight adjustments for English spellings.

The only reason we can be sure of these names is because they are recorded in the immigration barracks’ ration book. When the Fritz Reuter arrived in Wellington, its passengers were at first not considered immigrants and officials were under no obligation to record who went where.

A return of immigrants who arrived in Wellington between July 1876 and July 1877 showed that 202 of the Fritz Reuter passengers had been sent to “other ports” but it does not say who or where. The same return assumed the balance of the passengers—309—stayed in Wellington, but that seems unlikely. Single women and men who could not speak English might have been able to find jobs, but what opportunities would there have been for farming labourer families in the city?

_______________

Marianna and Paul Biesiek, whose 22-month-old daughter died at sea, had three sons in Taranaki. Paul Adam Biesiek and his brother Joseph both married other first-generation Poles, Mary Dravitzki, and Mary Ann Potroz, and Thomas did not marry. All of them are buried with the senior Biesieks at Inglewood Cemetery.

While first marriages between the Polish settlers tended to be with other Poles, as the younger of the 900 first settlers, and the first generation of children born in New Zealand went to English-speaking schools, it was inevitable that daughters’ names would change.

The other Polish families who first walked into Inglewood had first-generation daughters and a widow whose names became Williams, Crombie, and McKenna (Doduński); Hastie, Wells, and Christensen (Duszyński); Fryday, Collins, Reid, Todd, Fullforth, Fox, Meyer, Wilson, Binderbeck, and Wairi (Myszewski); Fawcett, Roberts, Bright, Arnold, James, and Hart (Neustrowski); Miller, Miskler, Clark, Jans, Coe, Newbold, Grey, Robson, Davies, Rayner, and Braggins (Potroc); Wheatley, Patten, Latham, Betts, Hogg, Gray, Tapp, Rowe, Neill, O’Neill, Stewart, Phellan, Carey, and Moosman (Uhlenberg); Summerhays, Ansford, Williamson, Moore, Douglas, and Walsh (Volzke).

Cemeteries in Taranaki hold by far the largest number of first-generation Poles—763—more than twice as many as in any other New Zealand region. Inglewood Cemetery has 272, Stratford’s Kopuatama Cemetery has 136, and in New Plymouth, there are 94 in Te Henui Cemetery and 63 in Awanui Cemetery.

Cemeteries in the Manawatū-Whanganui region hold the next largest number of first-generation Poles—360—followed by Otago with 331, and Canterbury with 308. The 71 first-generation Poles in Clareville Cemetery north of Carterton and the 64 in Archer Street Cemetery in Masterton boost the Wellington region’s numbers to 272, with its city cemetery in Karori holding 75.

Although the West Coast had only 122 first-generation Poles, the Hokitika Municipal Cemetery, with 84 early Polish settler burials, comes in at number six in New Zealand. The scarlet fever epidemic in 1877 hit Hokitika hard and resulted in the disproportionately high number of children buried there that year.

A new headstone at Hokitika remembers Rogucki siblings Leo (5) and Barbara (2), who arrived via the Fritz Reuter with their parents, Michał and Anna Rogucki, and their 10-year-old sister Cecylia, who later married George Bentley-Payne. Leo and Barbara died of scarlet fever on 30 July and 8 August 1877, and it did not sit well with Cecylia’s great-granddaughter Judith née Payne Stephens that the two were buried without headstones under names incorrectly spelt (Michael and Banula Ruska) and apart from each other.

One proudly Polish headstone stands out among the 14 interred in the Taruheru Cemetery in Gisborne: that of Anna Shaskey. Under her name and between the Polish and New Zealand flags is the name Jaroszewski, the one she, her husband and four children arrived with in Lyttelton in 1872. The next lines show that she was born in Poland on 1 June 1836, that she died in Gisborne on 7 March 1931, and that she was the loved wife of Mathias.

On his naturalisation papers in Papanui in 1893, Mathias signed himself as Matthew Shaskey, farmer, but a newspaper report in The Akaroa Mail about how he and his son thwarted an attack by a small, white bull shows he was already using that name in 1881. By then he may have been tired of struggling to get New Zealanders to spell it correctly. Mary Anne, the family’s third child born in New Zealand, in 1878, is the only one registered as Jaroszewski, yet the record takers still managed to spell her father’s first name Maththep. Christchurch Christening records show that Mary Anne was baptised as Sarsevski, yet her father was Matthias Jarsevski.

Matthew Shaskey died in Christchurch in 1912. The wording on his widow’s headstone follows his in Linwood Cemetery. His Polish name is in parenthesis, and it states that he was born in Poland.

The Jaroszewski name may have disappeared from the official record of New Zealand’s Births, Deaths and Marriages, but it is clearly marked in Taruheru and Linwood.

On Jaroszewski-Shaskey plinth in Gisborne are words fitting so many of New Zealand’s early settlers:

“Bringing another thread to our tapestry of nationhood.”

—Barbara Scrivens

1 June 2025

_______________

To read more stories about the early Polish settlers to New Zealand, go through the menu at: https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/early-settlers/

If you would like to comment on this post, or any other story, please email editor@polishhistorynewzealand.org/

Jackson’s Bay – 150 Years On

Jackson Bay put on a pageant for its sesquicentennial last weekend. The sea sparkled. The sandflies hid. The wind behaved.

Anyone who arrived, however, had to drive around the substantial heaps of debris that slipped down the mountain just a few weeks earlier: a reminder that this beautiful spot should never be underestimated.

Descendants joined friends, guests, and visitors who happened to be there at the time, to commemorate the day that the area’s first settlers waded, were rowed, or were carried ashore on 19 January 1875—a year when 3,000 mm of rain fell on 186 days. The 24 men, 14 women, and 49 children of unknown ages, came from Scotland, Sweden, Ireland, England, Denmark, Canada and Germany. No road then, and no jetty, which was only built in 1939. Schooners waited in the bay while dinghies offloaded people and their possessions.

During the rest of that year and until July 1876, another 109 men, 50 women, and 116 children from the same countries, as well as Poland, Norway and Italy, waded through probably chillier seas. Still others—such as the Polish families of Francizek Kurowski and Robert Lipinski—arrived later in 1876, enticed by the glowing promises that the colonial government advertised.

They were divided into groups along the 20-mile length of what was officially named the Jackson’s Bay Special Settlement. The first mostly English-speakers were offered the only 10-acre sections south of the Arawhata River, on the left-hand side of the photograph below. The rest of the sections were mostly 50-acres. Scandinavians were sent farther north to the Waiatoto River. Italians—who dreamt of growing grapes and vegetables—went even farther north to the swampy plains of the Okuru River. Most of the Poles were offered sections directly inland and south of the Jackson’s Bay beach, along the banks of the Smoothwater River that runs along the narrow valley between the Stafford Range and Burmeister Tops.

It did not take long for dreams to fall apart for settlers like the Poles, who had fled Prussian persecution and arrived with few possessions and little money.

The deal at Jackson’s Bay (150 years ago, its name had a possessive) was that settlers were guaranteed paid work for three days a week at eight shillings a day, and were expected to use the rest of the week to clear and improve their sections. But the work did not materialise, and high prices at the government-sanctioned general store meant 24 shillings a week was not enough to keep a family fed and clothed.

The Poles knew how to work land—they had been mostly farming serfs—but they soon found out that they could not grow even the most basic of vegetables on their bush-clad and flood-prone sections in the extremes of weather.

South Westland could not have been more different from the wide, fertile plains of northwest Poland, land they would not have left had it not been for their lives becoming more and more squeezed under Prussian rule. (Poland had been partitioned by its three empire neighbours for the first time in 1772, and 100 years later in its Prussian-partition, Polish schools had been banned, as had the language, any written work, the Polish spelling of their names, and even Catholicism, the faith of most Poles. Even worse, all Polish men were automatically conscripted into their oppressor’s strict 20-year conscription system.)

Today, a Department of Conservation sign and a marker show the steep beginnings of the track to Smoothwater.

When any of the settlers tried to supplement their incomes by taking jobs elsewhere, the resident agent Duncan Macfarlane—a former merchant from Hokitika—punished them by excluding them from local contracts. Thanks to his signature apparently needed on any salary cheque, he controlled all the settlers’ salaries, no matter where they worked. He ran the store through a system that guaranteed indebtedness. At the time of the 1879 Commission of Inquiry into the complains against the settlement, 58 of its families owed nearly £4,000.

The Poles had all left, destitute, by 1879. For the Poles and Italians, the inability to speak English had not helped.

The only thing that all the settlers agreed on was that they needed a jetty, estimated to cost £1,500. Without that piece of infrastructure, and with a fickle sea, getting goods to and from Jackson’s Bay was unreliable. Even if there had been a regular market for fish, for instance, produce from the bay was likely to be spoiled before it got to market. The same went for fresh goods arriving: the commission heard several complaints about rotten seed potatoes arriving at Jackson’s Bay.

Macfarlane seemed to get a ministerial go-ahead for a jetty in 1878, and even started the build, but it was thwarted. By the time it was finally built in 1939, a regular air service to Haast and Okuru had been running for eight years.

Visitors to Jackson Bay these days arrive by road. My husband and I travelled via Hokitika, where several of the Polish Jackson’s Bay families later moved. Our waitress at the Station Inn was surprised that there were any Poles among the settlers. She had lived on the coast for 40 years and had never heard of any, which prompted my counting: of the 362 people who arrived in Jackson’s Bay between 1875 and 1876, 130 were Poles. By the time the last Polish family left in 1879, 15 babies had been born and one—Joseph Gorowski—died at six weeks in April 1878. In June 1877, a tree that fell on their house in Smoothwater crushed mother-of-three Rosalia Wicki, and a year later, Franciszek Kurowski perished in a boating accident and left his pregnant widow with four children.

_______________

Jackson Bay is where South Westland’s coast road ends. Apart from the area immediately adjacent to the beach, none of the “town” of Arawata on the ambitious 1875 map below was ever built. The Esplanade today veers left on what was Pier Street and peters out. Not that anyone needs a street address in Jackson Bay. Directions do nicely.

Organiser of the sesquicentennial, Kathryn Bennie—who bought a bach on Pier Street with her late husband, Ewan, 14 years ago—suggested we walk across the valley to the other side. It is the High Street on the map below and runs along the dip between the hills in the photograph above.

Jackson Bay’s planned High Street in 1875 is now the Wharekai Te Kou walk to Ocean Beach, below.

On a sunny day it is difficult to imagine a rainfall of more than 3,000 mm. There is little sign of the landslip of December 1886—dislodged from the mountain behind after four days of torrential rain—which covered the hotel and washed away the owner’s 13-year-old son, Charles Robinson. If there were more roads in the town, they are now hidden by the fauna now growing over the slip.

Kathryn: “The wairua of the place instantly took hold of me and I was compelled to find out who the people were who are buried in the cemetery. It bothered me that there were no proper records anywhere. I delved in. Little did I know it would take me on such an incredible journey that would keep exploding at every turn. During that process I automatically ended up with files on the families.”

Kathryn’s research has led to a permanent information board in the DoC kiosk opposite the Craypot that lists all the families of the 1875–1879 settlers.

She and other volunteers have also cleared away slips from Arawhata cemetery, and uncovered graves of those interred there. Few have names or headstones, and many are marked by moss-covered rocks that could have been easily overlooked last weekend had it not been for volunteers placing hydrangea flowers on each one. Below are the three Heveldt graves.

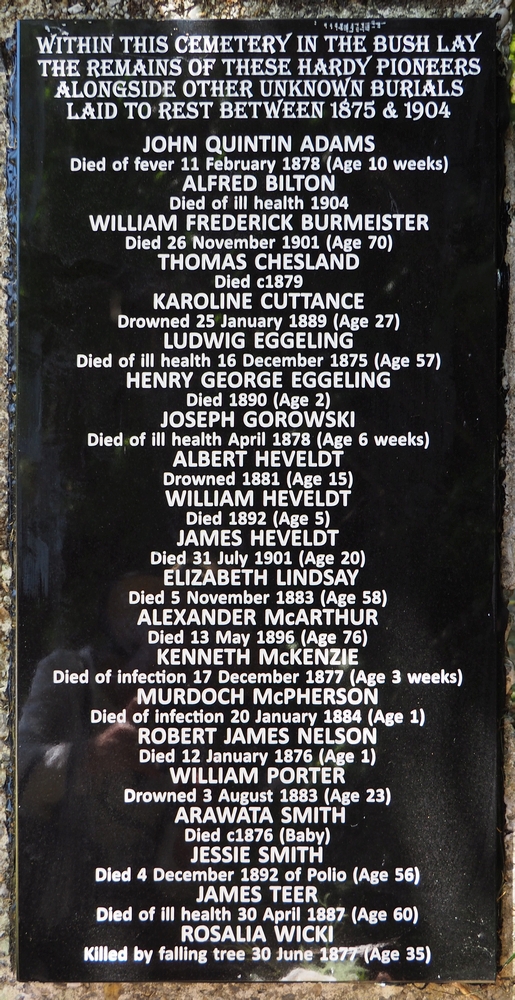

Kathryn knows there are others hidden elsewhere in the bush, but those whose names she has been able to verify now have a permanent plaque, unveiled on 18 January 2025 at the entrance of the cemetery.

Thanks to Kathryn, the “UNKNOWN Polish settler’s wife…” now has a name.

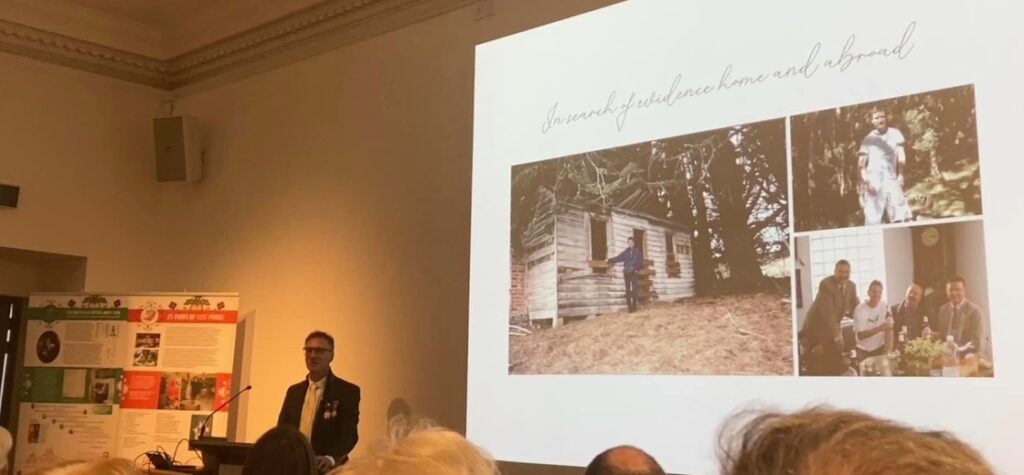

Above, Kathryn Bennie with Polish historians Ray Watembach, left, and Paul Klemick, at the Jackson Bay sesquicentennial celebration dinner. Ray is in traditional Kaszubian costume, and Paul in Kociewian, the two districts in Poland from where the Poles who arrived in Jackson Bay originated.

—Barbara Scrivens

27 January 2025

_______________

If you would like to comment on this post, or any other story, please email editor@polishhistorynewzealand.org/

For more about the Jackson’s Bay Special Settlement, go to https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/jacksons-bay/

For more photographs of the sesquicentennial, see https://www.facebook.com/jacksonbay150/

Blue Skies, Green Grass, and Warmth

The much-anticipated USS General George M Randall AP-115 eased her way into a sparkling Wellington on 1 November 1944.

As well as her beloved cargo of New Zealand sons, husbands, and fathers, the troop ship carried 733 Polish children and teenagers—mostly orphans—and their 105 caregivers.

_______________

Thousands of beaming New Zealanders on the docks matched the excitement on deck, the warm spring weather perfect for celebrating the Second New Zealand Expeditionary Force’s return from action in Greece, Crete, Italy, North Africa and Burma.

The welcoming cheers paused as the children, who had never possessed a weapon or fired a shot in combat, walked down the gangplank with ill-fitting clothing and wary eyes. Boys had shaved heads. New Zealanders who read newspapers or listened to the radio knew of their impending arrival, but they were not prepared for the sight of so many people so young sharing a collective and distinctive atmosphere of hardship.

They were the lucky ones—survivors out of hundreds of thousands forcibly removed from their homes in eastern Poland in 1940 and 1941 and incarcerated in NKVD (Soviet Secret Police) forced-labour facilities throughout the USSR. They had sheltered in orphanages created by the Polish army as that army struggled to squeeze around 115,000 Poles—barely eight percent of those taken by the Soviets—out of Stalin’s territory.

Photographer John Pascoe boarded the ship that Wednesday. While most around her looked to shore, he caught the eye of this little girl, too small to look over people against the railings, and that of the little boy on the left-hand side of the foreground.

Earl Bailey, who worked for Movie News, stood at one of the gangways: “They were streaming off the ship, wondering no doubt what sort of a world it would be. There was no cheering that I can think of, but a solemn silence as the emotions of the Kiwis went out to the children. As a cameraman, I was visibly disturbed, and I still feel it.”

American personnel and Chinese airmen scheduled to train in New Zealand arrived with the 2nd NZEF. Dignitaries welcoming them included Prime Minister Peter Fraser, Minister of Defence Frederick Jones, Consul-General for China Wang Feng and several high-ranking American military officials. The Royal New Zealand Air Force band “added to the liveliness of the welcome.”

While New Zealand veterans embraced their loved ones, the much younger cargo waited to disembark. They had arrived at the invitation of the New Zealand government to spend the balance of the war “where they can continue their education and enjoy in the sanctuary of New Zealand the peace which their own land cannot at present offer.”

Local medical officials examined the Polish refugees. Possessions gathered, they then assembled on deck to receive their own set of dignitaries. Prime Minister Fraser joined Polish Consul Count Kazimierz Wodzicki and his wife, Maria, all instrumental in the Polish-New Zealand refugee arrangement. The Poles may not have understood Mr Fraser’s speech, but they understood the welcome.

A Polish girl recited in English: “Thank you very much for what you have done for us Polish children by inviting us to your beautiful country. God bless you. Long live New Zealand.” The children then sang to their Consul and the rest of the welcoming party.

One can understand the children’s quiet demeanour among all the fuss: Besides taking time to absorb their new surroundings, they were unused to seeing so many smiling faces. They knew adults as serious; all but the youngest of the children had intimate knowledge of hunger, extreme deprivation, and death. Many of them had seen family members die—during transportation to forced-labour facilities in the USSR; within those facilities; as they trudged hundreds of kilometres towards freedom; or in transition camps between Uzbekistan and Persia (now Iran).

A reporter for the Evening Post noted:

Except that some were still showing the effects of their sufferings in Europe [sic] and that some had the striking blonde beauty seldom seen in this country, the Polish children who arrived recently as guests of the Dominion were very much like New Zealand children. Yet there was a pitiful difference, and it lay in the fact that although they played about or watched visitors inquisitively, they made hardly any noise and spoke to each other in such soft, low voices that one was not even conscious that they spoke a foreign language.

The children provided a popular diversion on a transport ship that included many fathers. Another article told of:

… one of the most popular amusements on the trip [was] to line the deck rails overlooking the cargo hatch they had adopted as their main playground and to watch the young émigrés play, and it must be confessed, fight, during their voyage—a voyage which was for most the first time they had been on a ship and certainly the first time on such a friendly one.

For most of the newly arrived Poles, this had been their third experience on a ship. In 1942, many had crossed the Caspian Sea on old cargo vessels that lacked any designated sleeping, dining, or sanitary facilities. They left from Krasnovodsk (now Turkmenbashi) in Turkmenistan (then part of the Soviet Union) and landed in Pahlevi (now Bandar-e Anzali) in northern Persia.

Soldiers enlisted in the new Polish army left the USSR first. They shared the crossing with orphans and their caregivers. The last transports carried mostly civilians. Ragged, skeletal bodies filled every available space. Stormy weather conditions created extra challenges on some of the 43 trips. Those who survived—after processing and disinfecting in Pahlevi—moved to military and refugee camps farther inland. Some of the orphans arrived in Teheran overland from orphanages in Ashgabat, Turkmenistan, through the Kopet Dag mountain range (Köpetdag Dagersi) and via Mashhad.

Most of the parentless Polish refugees settled in Isfahan, which became known as The City of Polish Children. Some of the children had arrived through authorities such as the Red Cross. Some had been left in Russia by desperate mothers unable to feed them and who believed they stood a better chance of surviving in the institutions. Some had said goodbye to their parents when they joined the army. Some had siblings. Some had mothers working in the orphanages.

The 838 Poles accepted by the New Zealand government gathered as a group for the first time at a transient camp in Ahwaz near the Persian Gulf. The cargo steamship Sontay took them across the Arabian Sea to Bombay. Józef (Joe) Jagiełło, then eight years old, remembered that “slow cargo ship” as:

“… terrible, they didn’t have facilities for us and we were getting rations of smoked fish and bread and water. For years afterwards I hated the smell of smoked fish.”

He described the USS General Randall as:

“… like heaven… It was such a huge ship, there was plenty of room to run around in… everybody had bunks… the cookhouse never closed.

“I forget how many cookhouses or dining areas there were, but they never seemed to run out of food. Whenever we felt like having something to eat, we’d look through the door, and the cooks would see us, and they’d wave at us to come in. They’d sit us down and bring us food. It didn’t matter when.

“It was the first time I sat down for a meal. There were knives and forks, and we didn’t know what to do with them. They had to teach us how to use them. For the first time we had Weetbix and Cornies [Cornflakes] with milk—and sugar—and bacon and eggs and the food was cooked. You had hot meals.

“There were certain places they wouldn’t allow us to go, but we were running up and down ladders, and things. I still remember there were four bunks above one another, they were swinging bunks, and that was great. They got us organised to do an escape drill. They blew a siren, and we had to rush up and put lifejackets on and we’d go to the [life]boats.

“It was great when they used to practise shooting. A little monoplane used to come and towed this huge balloon behind it and the guys in the Navy would start shooting, and when they hit the balloon, we’d all cheer.

“They used to have a practice when the siren would go, and we used to notice the boat would zig-zag. We used to watch the wake, and they said it was in case there was a submarine or something… We were going across the Indian Ocean.”

The ship’s doctor had his hands full:

… kept busy attending to bruises and abrasions, but the general health of the children had been much improved by the sea voyage and wonderful care.

At five in the afternoons, troops were:

… ordered to their quarters and the children given the freedom of the decks until after seven. When the time came for the children to go below, the order was given in Polish over the loud speakers. It was not long before the men could reel off this order, unaware of the meaning of the words they were pronouncing, and as soon as the order started to come through the loud speakers the men all over the ship took it up and chanted it with good humour at the tops of their voices.

The Polish children acknowledged the ship’s hospitality with a concert for the officers. A New Zealand soldier taught the older girls his national anthem, which they sang to a surprised audience at the Palmerston North railway station when their trains stopped for water and refuelling.

The photographs taken of the children the day they landed tell their story better than any words. There are smiles, some hesitant, some bright. There are eyes that had seen too much. There are frozen lips. There are hugs for the New Zealand soldiers holding some of the younger children, and laughing responses to the men’s own smiles.

According to the Auckland Star that day, the youngest refugee on the ship was 14 months and the oldest a 72-year-old woman. The adults included 42 teachers, two doctors, a dentist, four tradesmen, 36 single women, and six single men.

The sole toddler was with her 21-year-old mother. The youngest children were four. There were 132 families of two people, 44 of three, 19 of four and 14 of five. Four families had six members and three had seven.

One family of eight siblings ranged in ages between eight and 17. In another, a 15-year old sister, Anna Mokrzycka, had seven siblings, the youngest six. Sister-guardians from seven other sibling-only families became staff at the Pahiatua camp. Only two families arrived in New Zealand with both parents.

The group’s still living missing fathers, brothers and sisters were in the Polish army, either having fought in northern Europe and Italy or with the Polish military cadets in the Middle East.

During the Poles’ escape from Russia, it was an advantage to have a family member in the Polish army because the entire family automatically came under its auspices.

_______________

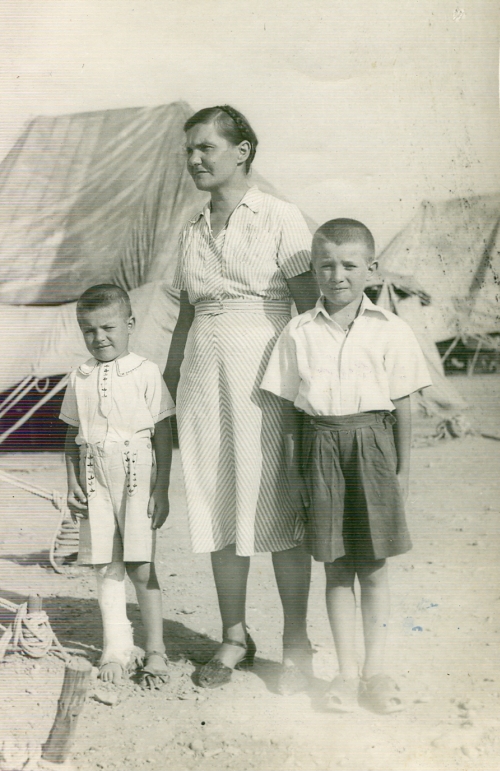

Most family groups arriving in New Zealand had single mothers, some shown above. Two single fathers accompanied their children. Men not accepted into the army were generally medically unfit or too old. The group included a priest and three nuns.

Nearly 200 children and teenagers between five and 15 had no familial connections, almost 60 of them younger than 10. Joe then still believed his father, Franciszek, was alive and continued to make up reasons for his lack of letters.

Fifty years later, a chance visit to the Auckland Museum led Joe to discover that by the time he landed in Wellington, his father had already been killed in action in Italy. Franciszek and Joe had travelled together to the Polish army’s enlistment station in Ashkhabad, southern Russia, after Joe’s mother and grandmother died in Siberia. Joe last saw Franciszek when he left for training in Egypt. Joe moved from one orphanage to another until he was selected to travel to New Zealand.

On that flawless Wellington day, Joe soaked up the smiles in the crowds on shore.

“When we arrived in New Zealand we thought what a lovely place it was because it was so nice and green and there were all these little houses up on the hills. It was so beautiful. The harbour was like a lake. We couldn’t believe we were in such a beautiful place, after being in Persia where everything was always sort of brown.”

For Joe it got even better when he was ushered onto a train.

“We didn’t know where we were going but we were so pleased that for the first time we went on a train that actually had seats! We remembered being on cattle trucks or freight trucks where there was no seating to sit on, you had to sit on the floor or stand up and all of a sudden we had seats to sit on and the train slowed right down at every little railway station and there were thousands of people waving and clapping and everybody laughing, you know, and cheering us.

“… and we thought, ‘They’re all happy, everybody is happy to see us.’”

—Barbara Scrivens

First published in 2015; updated September 2024

For details about the photographs and quotations regarding this story, please go to https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/blue-skies/.

For more stories about the Pahiatua refugees, please go to the page https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/war-immigrants/.

The First Polish Armoured Division

Eighty years ago today, 2 September 1944, they buried my maternal grandfather, Władysław Surowiec, at the side of a road on the same day he was killed in action in northern France.

He was 36, and a bombardier in the 1st Anti-Tank unit of the 1st Polish Armoured Division (1PAD). His military death certificate shows he had three children, which indicates that he knew that his younger daughter, Eugenia, had died in Uzbekistan. He was spared the realisation that the war he died for did not save his country, and that his farm north of Zaleszczyki was handed over by the Allies to the Soviets.

His was grave number 29 of 40 on the road between Mianny and Cahon Gouy, near Abbeville, and he was among three from the 1PAD who died the same day in a place I could not at first find—Gonny sur Somme—which turned out to be Gouy, near the Somme river.

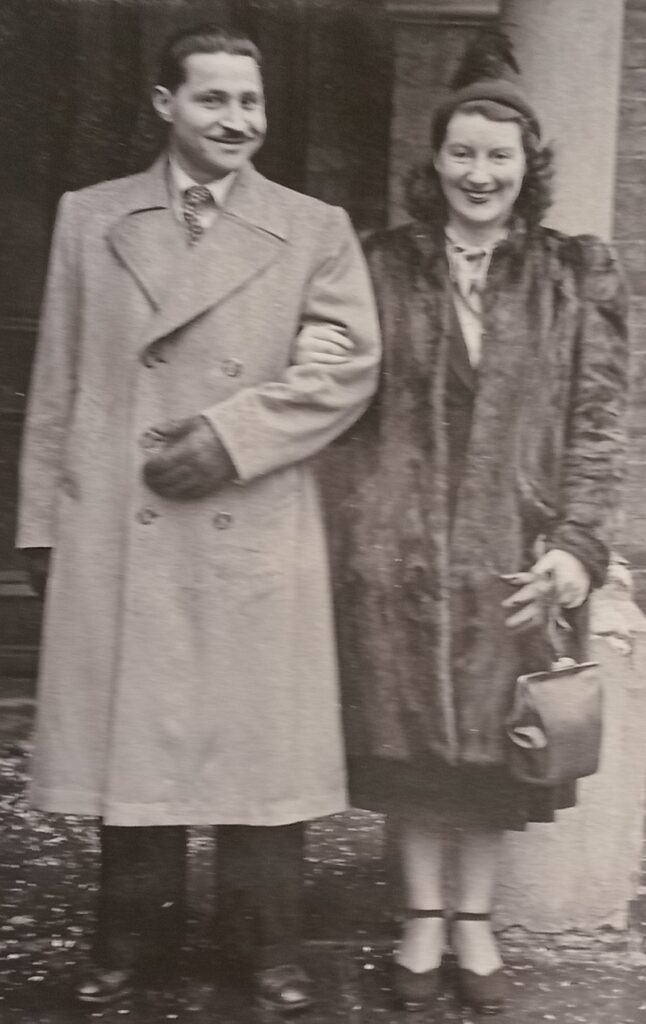

This is the photograph my babcia received after his death. A military historian answered my question as to why the insignia on his arm was scratched off: he, like so many others, was wearing a borrowed 1PAD jacket, identified by its black epaulettes.

“No, this can’t be right,” said my mother when she saw the word “Czortków” (Devils) in his military papers, but by then I had read Evan McGilvray’s The Black Devils’ March – a Doomed Odyssey, and could assure her that that was the name that the 1PAD became known as, and it was probably more for their wizardry in the field than any devilry.

This was the man who showed me that our family history was real, under circumstances that were such a coincidence, maybe it did involve a bit of magic on his part. I remember the date exactly, because it was Anzac Day. The year would have been either 2007 or 2008. I happened to be making myself a cup of tea, turned on the TV, and caught someone on breakfast TV talking about a relative buried in a commonwealth war cemetery.

Before, all I knew of my grandfathers was that both had died in the war, one in France, one in Italy, but that any records were destroyed. The past was not something my family dwelled on in front of us, although I knew from the rowdy post-dinner conversations my father had with friends and family that there was something deeper.

That Anzac Day, I typed Commonwealth War Cemeteries (I did not then have the information about “side of the road”) into a search engine, and found a photograph of my maternal dziadek’s headstone at the Canadian War Cemetery in Leubringhen, south of Calais. He lies with 18 other Poles, including “A Soldier of the 1939–1945 War, Known unto God.” I am glad they are under the care of the Canadians, because they fought some fierce battles before and after 2 September 1944. The cemetery is arranged so that the Canadian casualties embrace their guests in the middle section. Very polite.

_______________

The book helped me map out the route that the 1PAD, led by General Stanisław Maczek, took through France. The division had been formed in Britain from Polish soldiers defeated in Poland in 1939 who managed to escape the German and Russian invasions. The Polish soldiers who had reached Britain in 1940, were entrusted with the protection of the Scottish coast. General Maczek may have been as frustrated as his men with being out of the battle lines, but he used the time to train his men and rebuild his armoured unit. Several hundred men like my grandfather, who had escaped Soviet forced-labour facilities in 1942, helped make up the numbers needed for a full division.

Relations between British and Polish command were strained in 1944, which led to the Poles joining the Normandy invasion after the Allies, who they found stalled around Caen.

_______________

My husband and I followed the Polish route the best we could in September 2009. We started where the Poles landed on 29 July 1944 on the beach at Arromanches-Les-Bains, and where there are still signs of the massive Mulberry harbour construction blocks, and a museum on the seafront with Polish among the Allied flags.

The Poles cut through the Germans at Caen, pushed through the Falaise-Chambois pocket (Falaise Gap) on 23 August, and continued towards Abbeville, which the 1PAD captured on 3 September 1944.

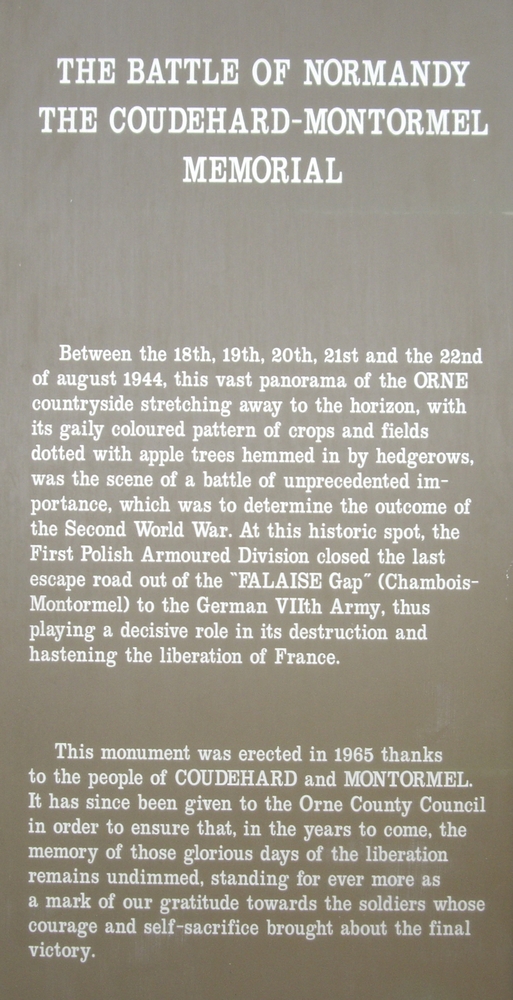

We found memorials in most of the towns and villages, like this one in Coudehard. A few kilometres away, Memorial Montormel Museum stands on the site of the August battle, on Mont Ormel, one of the few hills overlooking an otherwise mostly flat countryside. It shares the story of the four Allied units that removed the Germans from the hill: the 1st Polish, the 4th Canadian, 2nd French, and the 90th American.

Władysław Surowiec was promoted from rifleman to bombardier on 21 August 1944. During a battle that had according to one operational report lost up to 25 percent of its “fighting establishment,” it could only mean that he replaced someone.

I have trawled through orders of battles, trying to find more details about his anti-tank unit on 2 September, but they seemed to be quickly organised support regiments, attached to whatever other unit needed them to search out opposing tanks.

On 1 September, two anti-tank regiments headed with other 1PAD brigades and regiments towards Abbeville. At 10h30 the next day, reports came in of “contact with the enemy” and bridges over the Somme river near Abbeville blown up.

I am glad that my grandfather was not left long before being buried. And I am glad that he is now resting among the 704 men he fought with in northern France, and the two young men who died with him in Gouy: Tadeusz Szyszko and Kazimierz Popczyk, who served as Z Olesnicki, both aged 27.

The other Poles in the Canadian War Cemetery in Leubringen:

Stanisław Krzemionka, died in Abbeville on 1 September aged 24;

Jan Tyrna, who served as J Kos, died on 1 September aged 22;

Karol Dudek, died in Langannerie on 2 September aged 25;

B Telke, served as B Olszewski, died on 4 September aged 21;

E Pala, died on 4 September aged 24;

J Brzeżniak, died on 4 September aged 36;

B Skodda, who served as B Grabowski, died on 4 September aged 27;

J Ferenc, died 4 September aged 32;

A Zakrzewski, died on 5 September aged 29;

J Lipa, died on 5 September aged 26;

ZT Cwil, died on 5 September aged 18;

KA Manugiewicz, died on 5 September aged 27;

S Zabijak, died on 5 September aged 39;

J Broekere, died on 7 September aged 25;

C Żyżyk, died 24 September aged 34;

And the soldier known only to God. To you all, spoczywajcie w pokoju.

—Basia Scrivens

2 September 2024

_______________

If you would like to comment on this post, or any other story, please email editor@polishhistorynewzealand.org/

The Untold Stories Project

I remember as clearly as yesterday, the first time I stood in a school playground. The ground was grey, there were a few dark trees in the background, and the children running around were shouting things I could not understand. I looked elsewhere, but the babble did not change. I had been thrown into a strange, confusing pool.

I became a tortoise, comfortable in my shell. My parents did not help me with any homework I may have had; my father worked nights, and my mother had my three younger sisters to deal to, the baby six weeks old when I started school. I learnt to look after myself, developed a good memory, and a stutter.

I know I didn’t philosophise or question why I had to become “one of them” in the playground but I did. I absorbed the English language, loved reading, and my English accent was the same as my peers.

One of the first words I absorbed that was not in a reading book was “foreigner.” At first, I thought people called me that because I was born 30 miles away. It did not occur to me that it was because of my parentage, although at school, I did wish I had an easier surname. My mother called me Basiu, and a child overhearing her decided it was “Bash You.” I knew enough by then to say, “I’ll bash you in a minute!”

In my last year of primary school, I had my hand up an entire sewing class; we had to have our work checked before we could carry on. The next class, when the teacher again ignored me, I got up and followed her along the rows of desks. Finally, she turned around, asked me if I were a sheep, and told me to sit down. When she did look at my hem, she told me I had sewn it right-to-left instead of left-to-right and ordered me to re-do it.

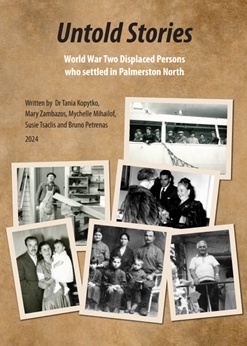

Those memories came back to me as I watched the documentary Untold Stories, about six families with origins in Belarus, Bulgaria, Germany, Greece, Latvia, Lithuania and Romania, who settled in Palmerston North. Most arrived in New Zealand as Displaced Persons, around 1951—10 years before I started school in England. The recollections of their children reflected mine in so many ways.

_______________

Mary Zambazos, the daughter of Konstantinos and Panayota Zambazos (pictured above with her mother and sisters): “The teachers at primary school made us feel different… I still have vivid memories of being told by one of my teachers when I was about seven or eight, ‘I bet you can’t wait to get married and change your name to Andrews.’ As a result, I’ve never changed my name, and I’ve given both my daughters the name Zambazos as a middle name.”

Tania Kopytko, the daughter of Michal Kopytko, has driven the Untold Stories project. Her father ended WW2 with the Polish army, and had been demobbed in England, but he was born in western Belarus. When the Soviets over-ran his country in 1939, the new authority ordered him to inform on a neighbour: Michael’s refusal led to his being sent to a gulag in Siberia.

Michael’s series of escapes from the gulag, the Soviet Army (after forced conscription), German prisoner-of-war and starvation camps, make the title of his section, A Lesson in Survival, a fitting one. He did return to his home village and was recruited by the occupying Germans to be a local village policeman. He was again forced to flee, and joined the Byelorussian partisans operating in the surrounding forests until the 1943 Soviet advance west pushed him and his colleagues the same way. When they were captured in France, their Polish papers convinced their captors that they were not Germans, despite their unfamiliar uniforms. They were given the option of moving to a Displaced Persons camp, or enlisting in the Polish army. Michael Kopytko made the only choice his conscience allowed, and he served with the Second Polish Corps in Italy and Egypt. He met and married Tania’s New Zealand mother in London.

Tania: “I became aware that our family was different from Kiwi families around us at a very young age… while Tania is popular now, it wasn’t then… and I had an unpronounceable and unspellable surname.

“On my mother’s side of the family, there were family members, and my grandmother, who were not happy that my mother had married a foreigner… You sense as a child that not everything is easy and that you’re a bit different.

“There was also Cold War prejudice. I felt that at College Street school. I remember children saying to me, ‘You’re a commie.’ I went home to dad and said, ‘What’s a commie?’ and he got so angry. He always brought me up to be strong.”

Mychelle Mihailof’s Bulgarian father, Zhelio (John), arrived in 1951 off the SS Goya. She tells how the DPs spent six weeks in the Pahiatua refugee camp undergoing intensive language courses:

“The assimilation policy of the 1950s meant that you took on New Zealand culture; you left your culture behind. You became a New Zealander, you took on the British way of life that we had here.

“He would have been happy too, but he found that you can’t give up your culture; you can’t give up what is inherently part of you.”

_______________

Their surname was constantly mispronounced and spelt in different ways, and John Mihailof never lost his strong accent, so he could never have been mistaken for a New Zealander. Mychelle recounted how he bounced between the two societies, not fitting in either, until he visited a communist-free Bulgaria in 1990 and cemented his European heritage:

“To know and embrace your whakapapa is so important. It’s the foundation for your identity, for your sense of self, the connection to the land and to the people that you come from.

“The people they mixed with were loud, colourful, their special occasions were filled with music and dancing and lots of drinking and lots of eating and different languages being spoken.”

_______________

Not all the European DPs in Palmerston North were as gregarious. Bruno Petrenas’s Lithuanian father, Felix, above, was “very quiet and very silent” about parents and six siblings, whom the invading Soviets sent to Siberia in 1939. He never saw them again. Felix escaped the Soviet army in 1945 when he surrendered to the Americans on the Elbe river. When he married Bruno’s German mother, Annielisa, both became Displaced Persons who were not allowed to live in Germany. They were among nearly 1,000 DPs that the Hellenic Prince carried to New Zealand in 1950 on behalf of the International Refugee Organisation.

Lucy and Martins Ozolins were on the same ship. They had had their farm in Latvia requisitioned by invading Germans in 1941, and had lived under constant threat of death if the Germans found out that they fed the slave labourers they were given.

In 1944, when the Ozolins realised that the Germans were retreating and the Soviets were advancing, they fled west. They stopped when they discovered they were in the safety of defeated Germany’s British Zone.

_______________

The Tsaclis family is the sixth and last represented in the documentary. WW2 put a stop to their three-generation merchant shipping business that operated around the Black Sea. A post-war communist Romania nationalised property and businesses, and “life became dangerous.” People disappeared or died and future craftsman joiner John Panayotis Tsaclis, then 18 and under threat of being sent to Siberia, fled Romania with his mother, Getta, to Greece. They arrived in Wellington in May 1951, John pictured here fourth from left.

This website is dedicated to people who, like the six families here, did not shout about their achievements, but simply got on with making new lives in New Zealand, and enriching their communities in the process. Tania Kopytko’s father became a postman who was able to rescue previously ‘undeliverable’ letters with writing unrecognisable to his English-speaking workmates, and got to know the wider DP community in Palmerston North. The tiny church he created from Tania’s converted playhouse attracted European neighbours with various home-languages.

With their large, productive vegetable gardens reminiscent of those left behind, their skills—ranging from joinery and cabinetry to cooking and dressmaking—their charm, strength, and an overwhelming desire to provide better lives for their children, the so-called Displaced Persons of Palmerston North found their own way of fitting in.

WW2 most disrupted the lives of people from invaded countries that were taken over by communism, such as in central and eastern Europe. Their refugees and displaced persons were often not wanted in non-invaded countries like England or New Zealand or North America, which needed them to help build their own post-war economies.

As a child, I was sheltered by a wider, strong Polish community in England, and am not surprised that the same happened here. The pressure to fit in is enormous but the inherent diversity imported through immigrants from different countries is what gave the bland Victoria sponge Englishness of the 1950s and 1960s the spice and vigour it lacked.

The documentary The Untold Stories Project is available through https://youtu.be/ZgbGneFehho.

This weekend sees the launch of the book Untold Stories – World War Two Displaced persons who settled in Palmerston North. Written by Dr Tania Kopytko, Mary Zambazos, Mychelle Mihailof, Susie Tsaclis and Bruno Petrenas, it provides details on the journeys of the six families to New Zealand, and their time at the Pahiatua camp, and includes a chapter on research processes and advice.

On Saturday 14 September from 2 to 3.30 pm, Palmerston North Central Library in the Square will host a presentation, discussion, and refreshments for people interested in the story and buying the book for $20.

On Sunday 15 September from 2 to 4 pm, the Untold Stories writers will be at the smaller venue at the Pahiatua and Districts Museum, 33 Sedcole Place, Pahiatua, to chat and answer questions.

—Basia Scrivens

10 August 2024

_______________

Apart from the first, the photographs here are from the exhibition of Untold Stories held at the Square Edge Community Arts Centre in Palmerston North last month. The last photograph of DPs arriving on the Goya is from the Evening Post collection held at the Alexander Turnbull Library in Wellington.

Other stories of Displaced Persons can be seen at: https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/janina-babka-iwanica/

https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/halina-kuzmiuk-aman/

https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/michal-pak-zenona-cyckoma-pak/

The Untold Stories book project has been funded by the Earle Creativity Trust and Palmerston North City Council Palmy history grant. For enquiries, and to order the book by post, please email untolds626@gmail.com.

_______________

If you would like to comment on this post, or any other story, please email editor@polishhistorynewzealand.org/

Monte Cassino

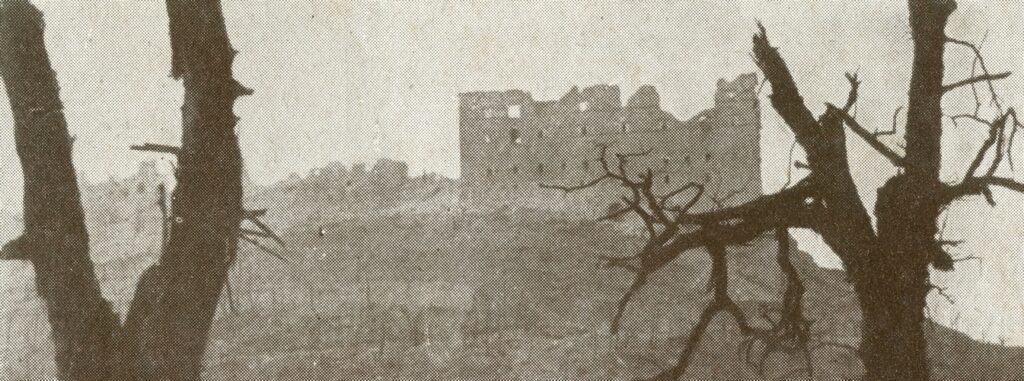

Eighty years ago today, 18 May 1944, at 10.20am, the Polish flag flew over the ruins of the Benedictine monastery on top of Monte Cassino.

The ruins had loomed over the soldiers of the Second Polish Corps in Italy, led by Lieutenant-General Władysław Anders, since they entered the fray surrounding Monte Cassino—the main stronghold of the German’s Gustav Line—on 3 March.

The crack German units, considered by German headquarters as of the “highest fighting value by virtue of their morale and special training” had defended their position since 20 January. The mountain completely dominated the surrounding hills and valleys, and allowed the Germans to thwart any Allied attempt at breaking through to Rome.

The first Allied units to take on the Germans at Monte Cassino were two American corps, and one French. New Zealand divisions replaced them when they withdrew, exhausted.

A second push in mid-February by the 2nd New Zealand and 4th Indian divisions, too, proved futile, and included the Allies’ bombing the monastery on the assumption that the Germans had been using the buildings: They had not, but their ruins provided even better cover than they already had. At this stage, the British Eighth Army took over from the American Fifth.

Anders addressed his “50,000 strong” soldiers via the radio on the eve of 3 March and reminded them of what they had been through in the “prisons and concentration camps” of the USSR. “We went through wild and deserted spaces and were decimated by frost, epidemics and our enemies,” he told his men. “We now follow the ancient road of the Dombrowski legions,” he said, referring to the Polish soldiers who fought in Italy from 1795, under the Polish general whose name became part of the chorus of a military song that became the Polish national anthem in 1927.

The Poles in 1944 joined the battle from positions on the east of the mountain, but started quietly, mainly in a communications role. Polish units went to the front line in the order that their transports arrived.

That third push for Monte Cassino fizzled out, and a few days before 23 March, General Leese visited General Anders at his headquarters in Vinchiarturo and informed him that the Germans’ “continual repelling” of their attacks on Monte Cassino had placed the Allied troops elsewhere in a “difficult position.” Leese had received the order for the British Eighth to break through the Gustav and Hitler lines, and gave that task to the Second Polish Corps, which had become a component of the British Eighth on 30 January 1944.

Anders, in his book An Army in Exile: “General Leese made it clear that he understood all that was involved. The stubbornness of the German defence at Cassino and on Monastery Hill was already a byword, for although the Monastery had been bombed, and the town of Cassino was a heap of ruins, the Germans still held firm and blocked the road to Rome.

“It was therefore clear that Monte Cassino, upon which the blood of five gallant nations—Americans, British, French, New Zealand and Indians—had already been shed, must be captured in spite of the German boast that it was impregnable.”

Polish headquarters moved to Monte Cassino, and had its own view of the monastery ruins. On 7 April, with General Anders reconnoitred the area, visited and received “much useful advice” from New Zealand General Bernard Freyberg and British General Charles Keightley, and started to lay out detailed plans, which included the need to:

– Build up huge stocks of ammunition and equipment, made difficult because the only two mountain tracks that could be used were under German observation and fire for 10 kilometres. The supply route could only be used at night, without lights; supplies often had to be carried in the last stages, by soldiers under fire.

– Organise a system of control posts connected by telephone.

– Reinforce and widen the tracks and roads for “all kinds of vehicles, including tanks.”

– Work under cover of smokescreens, to employ “every possible trick of camouflage” to hide artillery positions, supplies, and traffic.

– Hold practice sessions in fighting, mountain climbing, and for some squadrons, flame throwing.

By 6 May, all Polish commanding officers down to battalion commanders knew every detail of the coming operation, and its place within the Allied plan of attack.

A few days before D-day for the whole front, Polish soldiers waited in their positions on the mountain. They hid “under conditions of great hardship” in primitive shelters made from corrugated iron sheets, and large boulders, and under the Germans’ constant searching fire.

Nightfall of 11 May saw the beginning of the fourth and final battle for Monte Cassino.

_______________

The preparations were intense, but the battle conditions were far worse: The night and the smoke prevented the soldiers from seeing more than a few steps ahead; soldiers who had to frequently dive for cover lost contact with one another; the German projectiles came from all directions, including caves where they had stored their own supplies; the terrain prevented the artillery from helping the infantry.

As one officer died, his place was taken by the next in seniority. By 13 May, the Poles had withdrawn. Anders concluded that his men would be unable to “silence the enemy batteries” in positions on either side of the mountain slopes.

On 16 May, General Leese ordered that the British and the Poles co-ordinate to prevent the latter from fighting an “isolated battle.”

The second attack from the Poles was to start the next day, with “fresh battalions” but within the generally unchanged plan. Every Polish soldier available, was used.

Anders estimated that: “The enemy must be quite as exhausted as we were, or even more so, and that in the next day’s fighting… our attack, even if less powerful than our first effort, would achieve a definite success.”

He was proved right: on the morning of 18 May 1944, when the 3rd Carpathian Division renewed their attacks on the monastery, they discovered that the Germans had withdrawn most of its men.

Monte Cassino had been won by the Poles, who could not have been expecting such a quick victory, because the only Polish flag on hand was that of a patrol of the 12th Polish lancers, which flew until an official Polish flag was found.

An hour later, General Leese congratulated General Anders, who ordered the Union flag be hoisted next to the Polish one.

Anders’ description of the aftermath:

“The battlefield presented a dreary sight. There were enormous dumps of unused ammunition and here and there heaps of land mines. Corpses of Polish and German soldiers, sometimes entangled in a deathly embrace, lay everywhere, and the air was full of the stench of rotting bodies. There were overturned tanks with broken caterpillars and others standing as if ready for an attack, with their guns still pointing towards the monastery. The slopes of the hills, particularly where the fire had been less intense, were covered with poppies in incredible number, their red flowers weirdly appropriate to the scene. All that was left of the oak grove of the so-called Valley of Death were splintered tree stumps. Crater after crater pitted the sides of the hills, and scattered over them were fragments of uniforms and tin helmets, Tommy guns, Spandaus, Schmeissers and hand-grenades.

“Of the monastery itself there remained only an enormous heap of ruins and rubble, with here and there some broken columns. Only the western wall, over which the two flags flew, was still standing. A cracked church bell lay on the ground next to an unexploded shell of the heaviest calibre, and on shattered walls and ceilings fragments of paintings and frescoes could be seen. Priceless works of art, sculpture and books lay in the dust and broken plaster.”

The red poppies that kept blooming among the blood of the dead deeply affected the survivors. A few hours before the Poles captured Monte Cassino, one of the soldiers, poet and singer Feliks Konarski wrote the song Czerwone Maki na Monte Cassino (Red Poppies on Monte Cassino) about those poppies, and that blood. Another soldier, composer and conductor Alfred Schütz, wrote the melody.

On 18 May, 80 years ago, at the base of the mountain, the men of the Second Polish Army Corps cried as they sang the first two stanzas of Konarski’s song, its words apparently painted on a huge cardboard banner for the soldiers to follow.

My paternal grandfather survived Monte Cassino. Aged 47, he was in one of the supply units. I bought General Anders’ book in the hope of finding out more about what he had gone through, and I was grateful a few years later for the opportunity to interview Monte Cassino veterans, the late Władysław Błażków, Władysław Piotrkowski, Bronisław Bojanowski, and Adam Piotrzkiewicz, who talked about what it was like on the Italian battlefields.

The Polish Monte Cassino battles did not stop on 18 May 1944. The neighbouring hill, known as 575, was only “cleared of the enemy” the next day. Polish units then advanced to the Hitler line, on Piedimonte, and finally cleared the road to Rome on 25 May 1944.

The II Polish Army Corps’ casualty count after the Monte Cassino and Piedimonte battles:

Killed: 72 officers and 788 other ranks

Wounded: 204 officers and 2,618 other ranks

Missing: 5 officers and 97 other ranks

Total killed or missing in action: 962

Total wounded: 2,822.

—Basia Scrivens

18 May 2024

_______________

Photographs courtesy the late Władysław Błażków, who loaned me his 3rd Carpathian Rifle Division photograph album. The last is General Bolesław Duch saluting the battle’s dead.

Lieutenant-General Anders’ book, An Army in Exile; The Story of the Second Polish Corps, was originally published in 1949 and reprinted by The Battery Press, Tennessee, USA, in 2004, ISBN: 0-809839-043-5.

For more details on the 1944 military timeline, go to https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/1944-2/

See Władysław Błażków’s story at https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/wladyslaw-blazkow-2/

See Władysław Piotrkowski’s story at https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/wladyslaw-piotrkowski/

See Bronisław Bojanowski’s story at https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/bronislaw-bojanowski/

See Adam Piotrzkiewicz’s story at https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/adam-piotrzkiewicz/

If you would like to comment on this post, or any other story, please email editor@polishhistorynewzealand.org/

Happy Bursday, Mum

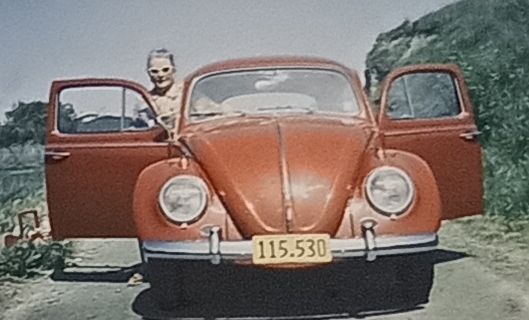

My mother would have been 90 today.

Kazimiera Nieścior never did get her tongue around the English “th” so it was always “bursday” or “Tursday.” And good “mornink” or good “moaning.”

My mother was charming. She told me how it worked for her when she got her first job in England, as a waitress at St Ann’s hotel in Newquay. She was 14. She could hardly speak a word of English, and said she managed by smiling and using the few words she knew.

After eight years in limbo, she could finally smile.

I would have liked to say that she “left school” but she didn’t have the privilege of what could have been called schooling. She was six years and three days old on a freezing early morning in 1940 when Soviet soldiers banged on the door of their little house in Smigłowo, a settlement of 50 houses—25 on each side of one road—just north of Zaleszczyki near Poland’s then southern border with Romania.

I would never have found out where the family went had it not been for a serendipitous letter that I wrote to the KARTA Foundation in 2010. It was one of those leads one tries without much hope. I was wondering why my father’s family was listed as being in an NKVD forced-labour facility yet my mother’s not.

It turned out that the NKVD (Stalin’s Secret Police), responsible for the forced labour facilities scattered throughout the USSR to which they sent around 900,000 Polish civilians in 1940 and 1941, either did not publish the lists of people sent to geographical Siberia, or those lists were lost. But the woman from KARTA said that my maternal grandfather, son of Józef (yes) born 1908 (yes) was deported with his children (there seems to be no mention of his wife, who was with them) to Taishet near Irkutsk.

Taishet is near Lake Baikal. I discovered that before and after the Polish families were there, it was classified as a GULag.

In Poland, children start school aged seven. In Taishet, who knows what schooling she received? She was eight when Stalin granted ‘amnesty’ to Poles in similar facilities throughout the USSR, and she, her parents, her brothers, and younger sister managed to get to Uzbekistan, where her father enlisted into the Polish army.

I still struggle to figure out how authorities worked out what would happen to the wives and children left behind. I know from reading Wladyslaw Anders’ book An Army in Exile, that Stalin kept provisions to civilians scarce, and I know from speaking with people that Uzbekistan was then a place with no food, no water, no shelter, and no jobs. My mother and her siblings became ill, and her little sister died.

My grandmother took my eight-year-old mother and her six-year-old brother Janek to an orphanage, and gave my mother the instruction to “look after” her brother. Until they were reunited two years later, my mother took looking after her brother seriously. It was made tougher in the orphanage in Tengeru, which divided the boys and girls. One day, my mother found Janek in the mortuary, supposedly dead from malaria. She shook him and he stirred from his unconsciousness.

She was 10, and I doubt whether there was anyone to check her reading. Although the authorities tried, they struggled to school the children of the more than 20,000 Polish refugees in the 22 refugee camps along eastern and southern Africa. In Tengeru, there were at least 2,000 school-aged children.

Lucjan Krokilowski, in his book Stolen Childhood: “The large concentration of school-age children in the African Polish camps required a proportionately large team of professional teachers and educators… but they were not available: younger male teachers were at the front [in 1942–1944], and there were few qualified females.”

In 1944, mother and Janek were reunited with their mother and older brother in a Polish refugee camp in Rusape, in then southern Rhodesia. Soon after, my mother heard that her father had been killed in northern France.

My mother was a tomboy, not surprising for someone who had lived most of her childhood outside. From what I could gather, Rusape was a paradise for the children. Fr Krolikowski on the attractions of living in the African bush: “… nor did the casual construction of the [school] buildings adequately separate the students from the ever fascinating surroundings outside.”

My mother was a disorganised housewife but a meticulous bookkeeper of the engineering business my father started in South Africa. I once said I’d give her the four cents she had been hunting for in the books, but she said no, that was not the point: she had to find her mistake. Her spelling may have been inventive but her accounts were always perfect—to the last cent.

My smell of childhood is burnt potatoes. My mother had no affinity with the kitchen. Her idea of making dinner would start with putting on some potatoes, then going into the garden. It frustrated my father, and taught us to cook for our own needs. Later, I understood why: she had never had a ‘normal’ home life. On the little Smigłowo farm, her mother helped her father plant up the new land whenever she could; in Taishet, the NKVD ruled, and they were lucky to get bread in their hands, never mind sitting around a table to eat; in the Polish orphanages, food arrived, as it did in the Tengeru and Rusape refugee camps, and at St Ann’s.

My mother loved gardening. She was never afraid of bees—or the dark—but had a fear of even the smallest frog. She sewed like an angel. The refugee camps may not have taught children how to cook, and may not have had qualified academic teachers, but the women taught the girls Polish handcrafts.

I remember my mother taking a dressmaking course. She made all our clothes, including coats, and our wedding dresses. She impressed me by the way she could take a piece of fabric, cut it out without a pattern, and hand it to me to sew an outfit for my Sindy doll. Sindy had a coat from the same fabric as mine. My mother taught me how to embroider and crochet, and follow patterns by just looking at the photographs.

For someone without a formal education, she didn’t do too badly.

Happy bursday mum. I miss you.

—Basia

7 February 2024

_______________

Łucjan Krókilowski, OFM Conv., Stolen Childhood, A Saga of Polish War Children, pages 97 & 99, 2001, Authors Choice Press, USA. Translated by Kazimierz J Rozniatkowski in 2001. The original, Skradzione Dziecinstwo, was published in 1983.

To read more about the background to the forced-labour facilities in the USSR, and the Poles’ escape, see: https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/missing-humanity/

If you would like to comment on this post, or any other story, please email editor@polishhistorynewzealand.org/

Danka and Ula

Sisters-in-law Danuta née Zioło Gawronek and Urszula née Gawronek Poczwa died within two weeks of each other, on Christmas Day last year, and 5 January 2024. They were connected by Pani Ula’s younger brother, Zdzisław, Pani Danka’s late ex-husband.

_______________

_______________

In every conversation I have that leads to a story on this website, I am aware that there are hundreds—thousands—of similar stories that do not get told, so each one is special. When someone dies, I struggle to go back to the original story to change the present into the past, so I hope that acknowledging them here will buy me some time.

Pani Ula was born in 1926, Pani Danka in 1934. On 17 September 1939, the Soviet Red Army rolled into eastern Poland, where both families had farms, Pani Ula’s near then-Brześć nad Bugiem and Pani Danka’s about 300 kilometres farther south near then-Tarnopol. Soviet soldiers woke both families in the early hours of 10 February 1940—along with around 200,000 other Polish mainly rural civilians—corralled them onto cattle-wagons, and took them to forced-labour facilities in the then-USSR.

Pani Ula’s family was imprisoned in one of the most northern of the Russian facilities in arctic Archangielsk; Pani Danka’s train travelled east, over the Urals and into Siberia.

Survival became an uneasy balance: when the train stopped, Pani Danka’s mother used to get off to beg for food—the soldiers had told them to pack the minimal for a ‘holiday.’ She continued to beg in the Soviet soldiers’ dining room at the forced-labour facility, and was occasionally thrown some bread. It did not prevent her baby, born months after they arrived, from dying of starvation.

Hunger, too, dominated Pani Ula’s existence. At 13, she was still too young to join the labour gangs, but became a shrewd beggar. In winter, she crossed the Dwina river and charmed the long-term Russian prisoners on the other side into giving her food to take back.

Nothing ever seemed to faze Pani Ula, despite the sorrows she had that began when her beloved mother died in an accident when she was eight: Pani Ula’s description: “She went from being a schoolgirl with rich parents to doing everything on the farm, and had three of us. … she was very practical, never scared to do anything. Probably, I’m a lot like her—good or bad, I just go forward.”

Poles in Wellington still remember the Kowhai delicatessen that Pani Ula ran from 1964 to 1979 in Main Road, Upper Hutt. She was unimpressed that in 1964, New Zealand law did not allow her to sign her own business papers, but did not let it stop her. She was determined to pay for her children’s education, and did so.

Both women had strong and special relationships with their siblings. Pani Ula’s with her older “gentle” sister, Celina, and her brother, six years her junior. Their bond was forged through living with a less than loving stepmother before WW2 upturned their lives further.

Pani Ula and Celina, who were taken in by the Polish army’s military cadet school in Egypt, and their father, Michał, who served with the II Polish Army Corps in Italy, settled in New Zealand through Zdzisław, who arrived in 1944 with 837 other Polish refugees.

Pani Danka’s saviour was her elder brother, Tadeusz Zioło, who cared for her and their younger sister, Alina, after their parents both died soon after escaping the USSR with the Polish army in 1942.

I have just re-read the story I wrote about the Zoiło siblings, sub-headed Surviving Paradise, and again noted the number of times that things could have gone so badly differently for the trio. There was the time the train in the USSR left without their mother. There was the time when their father decided to enrol Ted into the Polish army’s military cadet school, but the contingent left without him. There was the time the hospital in Pahlevi ‘lost’ the ill sisters.

In my introduction to the Zioło story, I mentioned that interviewing Tadeusz, Danka, and Alina together was both a joy and a challenge trying to keep up with the sibling chatter, but that there was no doubt of their shared love for one another, their camaraderie, and their absolute pleasure in one another’s company.

Pani Ula’s brother, Zdzisław Poczwa, died in 2001, and her sister, Celina Polaczuk, in 2009. Tadeusz Zioło died on 1 January 2020.

—Basia Scrivens

30 January 2024

_______________

To read more about Pani Ula’s journey to New Zealand, go to: https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/urszula-poczwa/

To read more about Tadeusz, Danuta and Alina Zioło, go to https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/the-ziolo-siblings/

If you would like to comment on this post, or any other story, please email editor@polishhistorynewzealand.org/

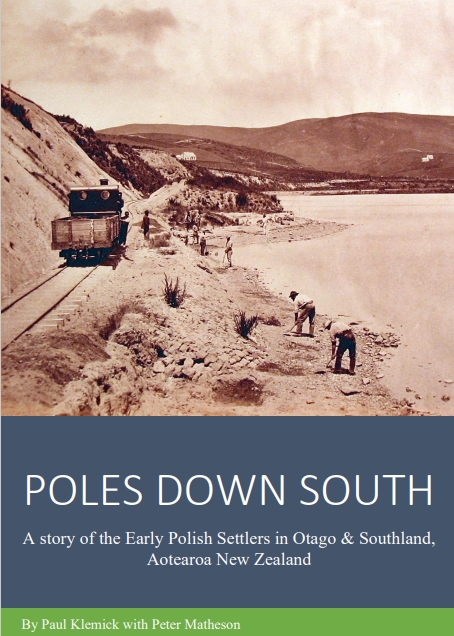

Poles Down South

Curiosity drives any family genealogist, and Paul Klemick is a curious man. He was also a curious child.

“I was very young, not even a teenager, when I asked my father where our name came from. ‘What do you want to know that for?’ he said, ‘That lot were all brought and sold as slaves.’

“He always called them ‘that lot.’ When I joined the Polish society some years later, he was still the same: ‘What did that lot ever do for society?’”

Rather than put off his second son, his father’s dismissal of his Polish roots further ignited Paul’s imagination.

“Who were these people? Why were my family like they were? Why did my father call my great-grandfather Phil the Flogger?”

Paul found out that his great-great-grandfather, Franz, arrived in Lyttelton harbour in October 1874, among the Poles aboard the Gutenberg. He was 18, and had travelled with his parents, Maciej Klimek and Anna née Smolińska, and his younger brothers Theodore (Felix) and Martin.

Paul’s great-great-grandmother, 17-year-old Franciszka Chełkowska, arrived in Port Chalmers nearly three months earlier. She was 17, and had travelled on the Reichstag with her married sister Veronica Anis and the Anis family. They settled in Waihola, as did Franciszka after she married Franz Klimek in 1882. Paul’s great-grandfather changed the family name to Klemick when he married Ellen Walsh in 1908.

Dunedin born and raised Paul started gathering and recording information. By the early 1990s, he was corresponding with Taranaki-based Ray Watembach of the Polish Genealogical Society, who had worked with academic Jerzy (George) Pobóg-Jaworowski on his book History of Polish Settlers in New Zealand.

In 1998, Paul answered an advertisement in Dunedin’s weekly publication, The Star, that invited people in the area to join the Polish Heritage of Otago and Southland. He went to the new society’s inaugural meeting, and met Patricia Clark, who had answered the same advertisement. Patricia recognised Paul—for years at Mass at St Paul’s in Corstorphine, she had sat in the pew behind the Klemick’s, and had seen Paul grow up. They found out that they were third cousins, once removed. They met other Poles.

POHOS planned its first exhibition of Poles in Otago, and gave Paul and Patricia the task of gathering material.

“There was no material then. Patricia and I visited and filmed people, and created an exhibition of what we found. By then, I had got to know other Polish people in Dunedin, and found people missing from George’s book.

“Before POHOS, I always thought it would be good to do something for the Polish people. They were a forgotten people, ignored, treated as if they were nobodies. I wanted to promote them in the community. Now they are culturally a part of the community, always counted in when there are cultural events.”

Paul’s grandfather believed the family was German, but Paul knew instinctively that they were not.

“I had a recurring dream as a little boy: I was in Europe, hiding from soldiers in barns, forests, all sorts of places, and always—just before someone saw me—I’d wake. I still remember those dreams.”

In 1994, Ray wrote to Paul: “Your letter is not straightforward, but full of enquiries…” and explained how the Germans, during their partitioning of north-western Poland between 1779 and 1918, germanised Polish names. Ray sent Paul books, church records, and Paul began to build a picture of not only his extended family, but also the families of other descendants of early Polish settlers in the Otago region.

“I spent so much time at the New Zealand Archives in Dunedin, I hadn’t been back for years, but when I popped in the other day, the lady there recognised me.”

Ray at first thought Paul’s family was Kaszubian, but that, too, did not sit well with him.

“At the first POHOS dinner in 1998 with the board members and descendants, I turned the menu over. On the back, were the cultural regions of Poland, and as soon as I saw Kociewie, I knew that was where we came from.”

Paul found his roots, and went three times to Poland to investigate them further.

Since the launch of his book, Poles Down South, in Dunedin this month, other descendants have asked why it took him so long to put together.

“I say to them, yes, it has taken all those years to put together, but it was tough to get my head around all the complex stories. We are all related in some way.”

I counted at least 116 Polish names in just one of the book’s appendices. As a fellow researcher, I appreciate the twists and turns that Paul would have faced in unravelling the information behind all those names, and the unexpected paths that he had to resolve as he followed threads and made sense of the stories attached to those names. This is an informative tome, filled with narrative, and backed by scores of pages of information that invites any family genealogist to pick up and follow.

From me, Paul, well done! I am proud of you and your tenacity. I continue to respect your staunch work-ethic, your dogged research, your patient kindness, and most of all, your unstinting curiosity.

—Barbara Scrivens

30 November 2023

_______________

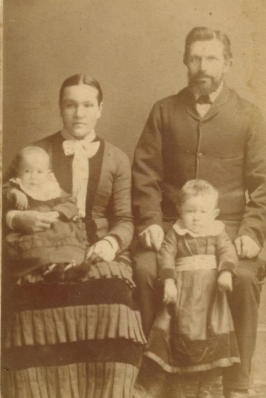

Anna Gruczyńska took the photographs at the book launch. The family photograph is from the Klimeck family collection. The book’s cover illustration comes from the Toitū Otago Settler’s Museum collection and is named Waihola railway workers.

_______________

To purchase a copy of Poles Down South by Paul Klemick, please contact POHOS through https://polesdownsouth.org.nz/book-launch-poles-down-south/

If you would like to comment on this post, or any other story, please email editor@polishhistorynewzealand.org/

Identity

Tell us a bit about yourselves, said the president of our Polish association after she had gathered her fellow committee members to the front of the hall.

The occasion was our commemoration in Auckland of 79 years since the Pahiatua children arrived in New Zealand.

I heard committee members to my right say they were descended from this or that Pahiatua family. Easy. This was a Pahiatua audience in a hall with a display of 12 pull-up panels showing Pahiatua history. Next to me, I heard my friend Anna say that her family had arrived here differently, through Africa, and I went along with that, because several members of my family had been through Africa too. I fumbled, said it was complicated, and froze. The four committee members who spoke after me were born in Poland, and had arrived here between two and five years ago.

It made me think. Anna and I happened to be stuck between Pahiatua and Poland, neither of which are identities that need explanation in New Zealand. If someone says, “I’m descended from such-and-such Pahiatua family,” Poles in Auckland know that they arrived in Wellington in 1944. If someone living here says, “I was born in Poland,” again, no explanation necessary.

But for those of us, like Anna and me, who came the long way around—not born in Poland, but of Polish parents and grandparents who went through the same trauma as the Pahiatua children, and who ended up in Polish refugee camps in Africa rather than in New Zealand, a 30-second explanation is inadequate.

Is it appropriate to tell a Pahiatua audience that the Pahiatua children were lucky, compared to those Poles stuck in east and south-east Africa years after WW2 ended? Soon after it became clear that Poland’s efforts in the war were in vain, and the country ‘given’ to Stalin in 1945 by her supposed allies, Great Britain and the USA, the New Zealand government invited the 733 children and their 105 caregivers to stay—if they wished.

This was a good year earlier than the Polish soldiers languishing in Italy after their heroics in battles such as the fourth, finally victorious one at Monte Cassino in May 1944. British MPs badgered the Polish soldiers to return ‘home’ to help ‘rebuild’ Poland. Most of the soldiers of Władysław Anders’ Second Polish Corps refused: the British MPs seemed to have no notion of the fact that the Polish soldiers had no homes to return to, because they were in the very part of Poland that had been gifted to the USSR. Besides not wanting to return to a communist-controlled country, they were also aware that the reason Soviet soldiers forced them and their families—at gunpoint—to leave those homes in 1940 and 1941, was because their names were on the Soviet Secret Police’s list of “anti-Soviet elements.” They had heard stories of Polish soldiers returning to post-war Poland, and disappearing.

While Pahiatua children, growing into adulthood, slipped into New Zealand society, those like my mother and uncles in Africa waited. The British government finally created the Polish Resettlement Act of 1947, and soldiers in Italy moved into disused army and air force barracks all over the UK. Slowly, their families were allowed to join them, and eventually also the widows of soldiers and their children. In 1947, the first ships with Polish refugees arrived in the UK from the Middle East and India. From 1948 to 1951, the African refugee camps emptied.

On 1 November 1944, groups of New Zealanders went down to the railway tracks between Wellington and Pahiatua to wave to the two trains carrying the Polish refugees to their new home in Pahiatua. They stopped for two hours in Palmerston North as residents there showered them with gifts.

The Poles who arrived in the UK received no such welcome. Rather, they were cold-shouldered. Veteran Adam Piotrzkiewicz, for example, told me how the residents of Cirencester made such a fuss about the Polish soldiers that they had to move. Still, as around 250,000 Polish refugees moved into scores of Polish resettlement camps in England, Scotland, and Wales, they developed strong Polish communities inevitably nick-named “Little Poland” by the locals. Outside of the camps, much like in New Zealand, other Polish communities flourished. Ours in Dunstable-Luton had a Polish Saturday school.