Identity

Tell us a bit about yourselves, said the president of our Polish association after she had gathered her fellow committee members to the front of the hall.

The occasion was our commemoration in Auckland of 79 years since the Pahiatua children arrived in New Zealand.

I heard committee members to my right say they were descended from this or that Pahiatua family. Easy. This was a Pahiatua audience in a hall with a display of 12 pull-up panels showing Pahiatua history. Next to me, I heard my friend Anna say that her family had arrived here differently, through Africa, and I went along with that, because several members of my family had been through Africa too. I fumbled, said it was complicated, and froze. The four committee members who spoke after me were born in Poland, and had arrived here between two and five years ago.

It made me think. Anna and I happened to be stuck between Pahiatua and Poland, neither of which are identities that need explanation in New Zealand. If someone says, “I’m descended from such-and-such Pahiatua family,” Poles in Auckland know that they arrived in Wellington in 1944. If someone living here says, “I was born in Poland,” again, no explanation necessary.

But for those of us, like Anna and me, who came the long way around—not born in Poland, but of Polish parents and grandparents who went through the same trauma as the Pahiatua children, and who ended up in Polish refugee camps in Africa rather than in New Zealand, a 30-second explanation is inadequate.

Is it appropriate to tell a Pahiatua audience that the Pahiatua children were lucky, compared to those Poles stuck in east and south-east Africa years after WW2 ended? Soon after it became clear that Poland’s efforts in the war were in vain, and the country ‘given’ to Stalin in 1945 by her supposed allies, Great Britain and the USA, the New Zealand government invited the 733 children and their 105 caregivers to stay—if they wished.

This was a good year earlier than the Polish soldiers languishing in Italy after their heroics in battles such as the fourth, finally victorious one at Monte Cassino in May 1944. British MPs badgered the Polish soldiers to return ‘home’ to help ‘rebuild’ Poland. Most of the soldiers of Władysław Anders’ Second Polish Corps refused: the British MPs seemed to have no notion of the fact that the Polish soldiers had no homes to return to, because they were in the very part of Poland that had been gifted to the USSR. Besides not wanting to return to a communist-controlled country, they were also aware that the reason Soviet soldiers forced them and their families—at gunpoint—to leave those homes in 1940 and 1941, was because their names were on the Soviet Secret Police’s list of “anti-Soviet elements.” They had heard stories of Polish soldiers returning to post-war Poland, and disappearing.

While Pahiatua children, growing into adulthood, slipped into New Zealand society, those like my mother and uncles in Africa waited. The British government finally created the Polish Resettlement Act of 1947, and soldiers in Italy moved into disused army and air force barracks all over the UK. Slowly, their families were allowed to join them, and eventually also the widows of soldiers and their children. In 1947, the first ships with Polish refugees arrived in the UK from the Middle East and India. From 1948 to 1951, the African refugee camps emptied.

On 1 November 1944, groups of New Zealanders went down to the railway tracks between Wellington and Pahiatua to wave to the two trains carrying the Polish refugees to their new home in Pahiatua. They stopped for two hours in Palmerston North as residents there showered them with gifts.

The Poles who arrived in the UK received no such welcome. Rather, they were cold-shouldered. Veteran Adam Piotrzkiewicz, for example, told me how the residents of Cirencester made such a fuss about the Polish soldiers that they had to move. Still, as around 250,000 Polish refugees moved into scores of Polish resettlement camps in England, Scotland, and Wales, they developed strong Polish communities inevitably nick-named “Little Poland” by the locals. Outside of the camps, much like in New Zealand, other Polish communities flourished. Ours in Dunstable-Luton had a Polish Saturday school.

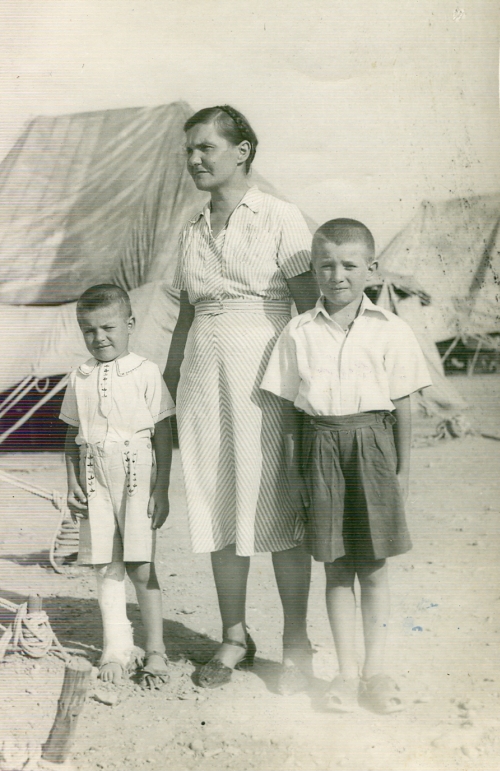

By the time I was born, my parents, paternal babcia, and uncles had moved on from the Stover Polish Refugee Camp in Devon, but my maternal babcia still lived there. Memories of spending every summer holiday there, with her and her second husband, always make me smile. They were lucky enough to be on the edge of the camp, and dziedek made a gate for access to the forest beyond.

We picked forest chanterelles. We played in the wild garden. We made money by finding lost balls in the golf course next door. When my father was there—he dropped us off the first week of the holidays and returned for us the last—we went to beaches and always, a trip to Hay Tor, where, after braving the rock, we gathered blueberries from bushes scattered among sheep droppings.

I know that my Polish childhood on the other side of the world was very different from the childhoods of those in our Auckland hall yesterday. Until we emigrated to South Africa, I had the best of both Polish worlds. I am grateful for that grounding, and I know that if I had to speak in a Polish hall anywhere in England, I would not need to explain much about my background.

—Barbara Scrivens

October 30, 2023

If you would like to comment on this post, or any other story, please email editor@polishhistorynewzealand.org/

To read about Adam Piotrzkiewicz’s story, go to https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/adam-piotrzkiewicz/