Taranaki’s First Polish Families

For years, a general story on Taranaki’s early Polish history seemed as impenetrable to me as the bush on the lower slopes of its mountain in the 1870s.

Descendants of the first Polish Taranaki families, when explaining their interwoven connections, inevitably ended with: “It’s complicated.”

The first Poles in Taranaki arrived off the Fritz Reuter, which carried more than 500 continental Europeans from Hamburg to Wellington in August 1876. The 260 or so Poles among them embarked in groups with other family or friends, and at first tended to stay in those groups. During their push for immigrants in the 1870s, the New Zealand government suddenly stopped accepting people from continental Europe. It apparently did not expect the Fritz Reuter’s arrival, and spent several months finding places to send them—away from the main centres.

The administration funnelled English-speaking settlers to more prosperous areas of the colony, like Otago with its goldfields, Canterbury, and Auckland. The non-English-speakers went inland to the Halcombe area, and settlements like Foxton, Whanganui, Hokitika, and Taranaki. The latter had developed a reputation for instability, thanks to the 1860s Taranaki Wars, which simmered with residual tensions between the colonisers and Maori who had had their land illegally confiscated.

The immigration barracks on Marsland Hill in New Plymouth accepted 52 of the Fritz Reuter passengers, among the first to leave Wellington’s stretched accommodation in mid-August. Of the 30 Poles among them, 27 walked out towards Inglewood in early September. Taranaki did not seem to receive the same funding as other centres. New Plymouth’s harbour was only finished in 1886, which prevented large ships docking, and allowed officials in ports such as Wellington to lure away many English-speaking labourers.

This worked in favour of the Taranaki Poles, because it allowed them to make a space for themselves, and later they were able to buy “waste” land—sections of that dense bush— at cheaper prices. The land carried a huge cost in labour, felling, stumping and clearing, but the Poles were patient, and cherished the stability that came with owning their own farms.

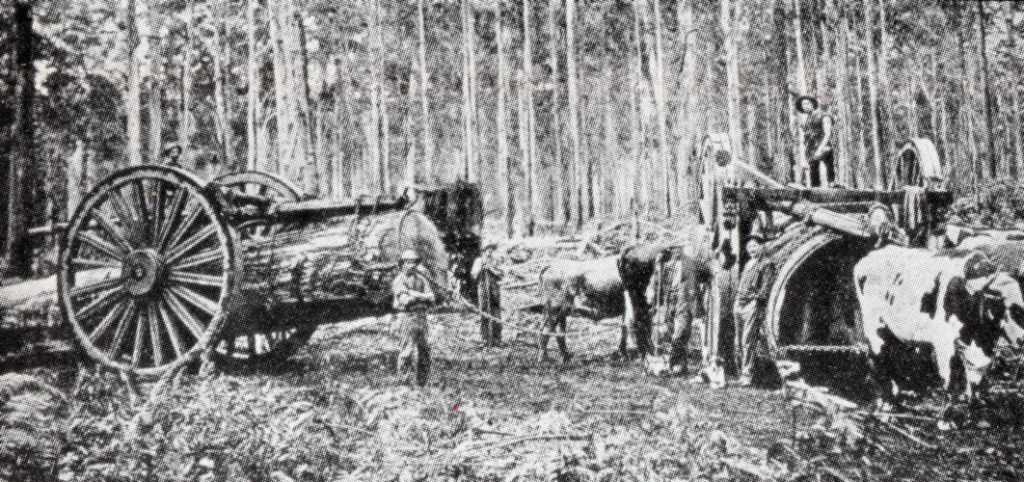

“Dense” is the descriptor attached most often to the bush that the first Poles walked towards in 1876, and this photograph shows just how dense it was. The many large trees sheltered a rampant undergrowth, still giving work to the settlers in the early 1900s, when this photograph was taken. The man on the left has been identified as Ben Dombrowski and the one in the middle as Paul Neustrowski.

During the late 1800s and early 1900s, Taranaki became home to the largest group of early Polish settlers, to the extent that young Polish men in other Polish settlements visited friends in Taranaki to become acquainted with its young Polish ladies.

Within a few generations, the original families, their married sisters and brothers with different surnames, marriages, births, deaths, and remarriages created a genealogical mass of relationships. I thought of it as a tightly packed ball of coloured threads of different thicknesses. Some families had helped me loosen some of the threads, but the ball remained largely intact, until I re-read a newspaper clipping celebrating 150 years since the first arrival of Devon and Cornish settlers in New Plymouth in 1841 that also mentioned Polish families receiving rations at Marsland Hill.

The clipping was among a growing number of files on Taranaki that sit on my shelves, with copies I had taken of the late Florinda Lambert’s transcriptions of news snippets from various Taranaki newspapers. She spent 14 years researching, and whenever I visited Taranaki, I made sure I spent a few days with the set of books she left to Puke Ariki.

Working on various early Polish family stories helped me understand more about their unstinting work ethic, their tenacity, and their pride in preserving their customs. That drew me to investigate and write about the Fritz Reuter in 2018. I tried to untangle why the New Zealand government, which so needed labourers, became so biased against continental Europeans. I called that piece The Human By-catch in a Colonial Immigration Industry because the people, the sentient beings who struggled to get here in 1876, were treated in such an unwelcome way—to the extent that the Fritz Reuter passengers are still not recorded on official immigration records.

Polish genealogist Ray Watembach and I examined the Marsland Hill immigration barracks ration book at Puke Ariki a year later. His Neustrowski great-grandparents, grandmother and grand-uncle were among those listed.

The large accounting book, divided by months, gave the names of exactly who had been in the buildings, and on what days. Eight of those names—Biesiek, Dodunski, Dusienski, Myszewski, Neustrowski, Potroz, Uhlenberg, and Volzke—became the core of the latest story in our Early Settlers page: Under the Mountain; Layers in the Mille-Feuille of Taranaki History.

The 150th anniversary article uncovered by Florinda Lambert shows the writer knew what they faced:

“Those who arrived in Taranaki in the 1870s or 1880s may have been able to step ashore at the foot of Mount Eliot [Marsland Hill] and walk only a few metres to find the comforts and services of a fairly substantial town, but once they turned their backs on those comforts and headed off into the virgin bush, they were as much on their own as any pioneers could expect to be.”

RW Brown captioned this photograph—in his book Te Moa, 100 Years of Inglewood History, 1875–1975—“Logging junkers in the bush.” It shows the engineering ingenuity used to drag the massive logs out of the bush, and the girth of those logs.

By 1879, Taranaki accepted Poles leaving “special settlements” along the West Coast, such as Jackson’s Bay, which imploded through under-funding and mismanagement. Taranaki needed as many willing labourers as it could get, and they soon joined other settlers in the bush. Although the Poles had been in New Zealand for several years, they started from scratch.

The Bielski, Bielawski, Crofskey (Kurowski), Lehrke, Stieller, and Zimmerman families arrived from Jackson’s Bay, and the Chabowski, Drzewicki, Fabish, Jakubowski, Kuklinski, Lewandowski, Meller, Rogucki, and Stachurski families from Hokitika, where many Polish families stayed after refusing to land at Jackson’s Bay.

Naturalisation records in 1918 included other Polish families, such as Dombroski, Drozdowski (Szczodrowski), Dudek, Dunik, Dusienski, Kowalewski, Pioch, Piontkowski, Schroeder, and Voitrekowsky (Woiciechowski).

These days, much of that impenetrable bush has been tamed, but I have the feeling that, while the Taranaki Polish family ball of interwoven relationships may continue to loosen a few of its threads, it will keep many close to its heart.

—Barbara Scrivens

29 June 2021

_______________

The Taranaki story is available at: https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/under-the-mountain/

The story on the Fritz Reuter is available at: https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/fritz-reuter/

_______________

If you would like to comment on this post, or any other story, please email editor@polishhistorynewzealand.org.