The Grofski (Grochowski) Family

Grochowski babies were being born in northern Poland on both sides of the Vistula for nearly 200 years before Simon and Franciszka Grochowski had their son, Franz, in 1869.

Then, their country—partitioned by Prussia, Russia, and Austro-Hungary since 1795—was not a happy place for Poles, and they left when Franz was two. They arrived in Lyttelton aboard the friedeburg in August 1872. The ship’s manifest had no trouble with spelling the Grochowski name correctly, or acknowledging the family’s Polish heritage, yet few subsequent records or certificates did the same.

Simon Grochowski’s 1883 death record, for instance, has him registered under the misspelling of his wife’s maiden name. Somebody chose a reason for the 38-year-old’s death without medical verification. Somebody chose to state that he was buried at a cemetery which has no record of him. Somebody else removed his surname from his young children’s and exchanged it for his own.

This is a story that has leant on various birth, school, marriage, death, and burial records. Not one of them is entirely correct, but together they shed light on this family’s early years in New Zealand.

The family name changed to Grofski about 10 years after Simon’s death. He was never known as Simon Grofski, so I continue to call him Simon Grochowski. He was probably Szymon, but I have kept to the spelling on all the records I have seen. Their marriage record has “Francisca,” but I have used the more common Polish spelling, Franciszka, or Frances, when talking about her personally.

This is in no way a complete history of the Grofski family; rather a look into its beginnings in New Zealand, and official information about them that was faulty more often than not.

Many thanks to Daphne-Anne Freeke, who allowed me the use of her compilation Franciszka’s Story 1847–1912, to Adrian Daly, who whetted my appetite with an intriguing array of family documents, and to Anna Gruczyńska, who found the hand-written Lynwood cemetery plans.

—Barbara Scrivens

BY ANY OTHER NAME

by Barbara Scrivens

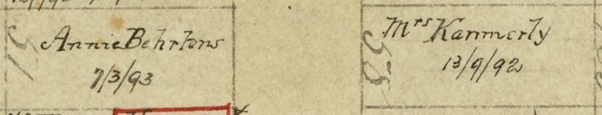

A tiny, wild, egg-yellow gazania has made its home among the unmarked graves where Mrs Kanmerly and Annie Behrtens lie opposite each other in Christchurch’s Linwood cemetery.

They were sisters, aged 16 and 10 at the time of their deaths. Their names on the cemetery records hide their identities and the tragedies of their short lives.

They and their four brothers were orphaned when their father, Simon Grochowski, died on 8 May 1883 on the farm where he was working in Tai Tapu. The family believed he became ill from drinking contaminated water, but his death certificate states he died of cancer. His death left his widow, Franciszka née Tadajewska Grochowska, with six children aged from six months to 13 years.

Less than a year before her death, “Mrs Kanmerly” was Mary Grochowska, six when her father died. “Annie Behrtens” was really Annie Pauline Grochowska, the six-month-old baby in 1883, and Mary’s only sister. Behrtens was a misspelling of her stepfather, Heinrich Behren.

It would have been impossible to know exactly where the Grochowski sisters lie in the cemetery had it not been for the hand-drawn map of Linwood cemetery. According to that, Mary Ann is under the tree and Annie is immediately next to the yellow gazania on the right.

The slice of the Linwood cemetery plan that shows how close the sisters are.1 The Christchurch City Council cemeteries database has recorded “Mrs Kanmerly” as Marie Kammerley.

The sisters were buried in what was then “free ground” in a Roman Catholic part of the Linwood cemetery. On the records, there is nothing to link them with their mother, who in 1912 was buried a few hundred metres away as Frances Arps, or their only other sibling buried in Linwood, their older brother, Francis Grofski.

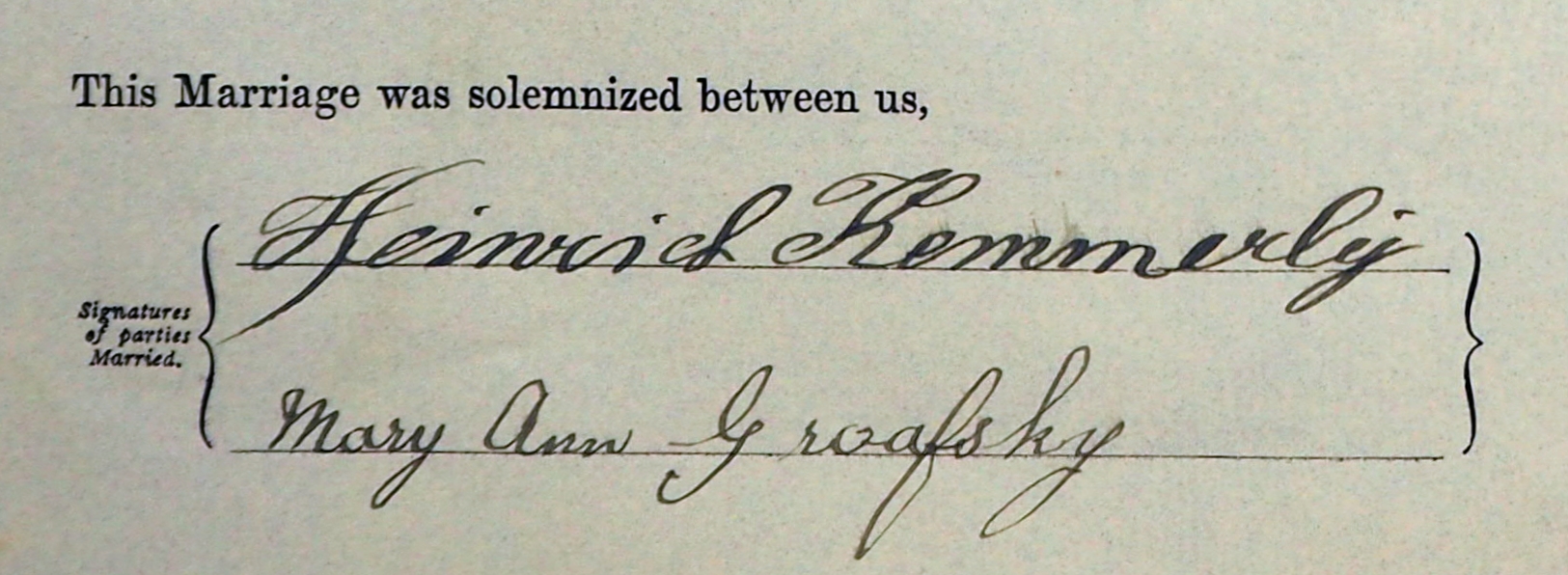

Mary Ann Grochowska was born on 14 December 1875. A few weeks short of her 16th birthday, on 26 November 1891, she married a Henrich Kemmerley at the St Mary’s Catholic church in Manchester Street, Christchurch. Her groom, 10 years older, had apparently arrived in the area eight weeks earlier.2 It is not clear what drew him to Christchurch.

Their marriage certificate shows that Mary Ann and Heinrich both resided in St Albans, that she was already 16, and that she was literate enough to sign her own name. The three witnesses all came from Marshland—Martin and Augusta Schimanski, and Annie Suchomski.

Although the Intentions to Marry index4 spelt her surname Grochowski—the same spelling used by the officiating minister, MT Marnane, on the marriage certificate—Mary Ann signed that certificate differently. This could have been because she had been taught by her illiterate mother.

The marriage certificate states that Mary Ann’s father was Henry Grochowski, and her mother was Frances Taklowoski. The first mistake seemed deliberate: Her stepfather had long assumed the position of Franciszka’s children’s father, and suggests he decided that his surname should match the bride’s. The second mistake was another in a long list of misspellings of her mother’s maiden name.

Mary Ann née Grochowska Kemmerley died the day after she gave birth on 10 September 1892, and the same day her baby was buried at Linwood cemetery. The Christchurch City Council recorded it as “Stillborn child Kammerly,” interred in Block 0, Plot 0.

More than 1,400 such stillborn babies share the same resting place in Linwood—yet there is no such block or row at the cemetery.

When Alexandra Gilbert was secretary for the Friends of Linwood Cemetery, she made enquiries. A former cemeteries administrator and a former sexton both told her that Block 0 Plot 0 referred to unidentified common ground. This, they said, could be under a bush, at the end of a row of graves or, as was the practice at Linwood, under the hedge surrounding the sexton’s house. According to the Linwood records, only 29 stillborn babies share their graves with another person.

It is not clear exactly who took on the role of administering a stillborn’s burial in the 1890s, but they did not discuss the procedure with the parents, nor record the exact location of the remains:

… when a couple had a still-born child, it was believed that if the mother had any connection with the baby, it would make the grieving period longer and harder. The father, of course, was not allowed in the delivery room in those days even when this was at home. The dead child would be put in an enamel bucket, covered with a cloth, and removed from the room immediately.5

_______________

The friedeburg at the port of Hamburg circa 1873.

Simon (28), Franciszka (24) and Franz (2) Grochowski were among the first large group of Poles to settle in New Zealand. They were lured by the colonial government’s 1870 Immigration and Public Works Act, which expanded its reach for labourers to include areas outside Britain. Immigration agents received £1 for each “statute adult” they landed in New Zealand and found hundreds willing to leave the oppression of Prussian-partitioned Poland. The Act defined a “statute adult” as anyone aged 12 or older, but children older than a year were classified as half-adults, so large families were profitable entities for these agents.

After the Prussian victory in the 1870–1871 Franco-Prussian war, German chancellor Otto Von Bismarck’s oppression of the Poles grew. Polish schools were already closed—the reason why so many of the Poles who arrived in New Zealand were illiterate—but in his bid to create a great monocultural German Empire after that war, Bismarck banned the Polish language to the extent that it was illegal to keep Polish books, or even documents. Worse for the predominantly Catholic nation, he also banned the practice of their religion. To add to the Poles’ disquiet was the Prussian’s strict and lengthy conscription system. Directly responsible for the Prussian victory in France, in 1870–1871 it not only forced Poles to fight for their oppressors, but also against the many Poles on the French side.

On 30 August 1872, the friedeburg anchored at Awaroa/ Godley Head, Port Lyttelton, with 294 people aboard, about 80 of them Polish. The ship’s manifest recorded Simon Grochowski as a German Pole, as it did for several others. Although Poland was not a geographical entity in 1872, other Poles were recorded as being from Poland or Germany.

The star in Christchurch devoted nearly one and a half columns of its five-column page three to the “first shipment of immigrants direct from Germany:”6

Three or four nations were there represented—the Germanic, the Germanic Polish, the Norwegian, and the Danish, all chattering away in the language and dialects of their respective countries… The immigrants were in the very best of spirits, and spoke hopefully of the future in their adopted home. Unfortunately, not one of them could speak English, and they expressed a considerable amount of anxiety in consequence, but they were in a great measure consoled when told that there were several of their countrymen in the province, and that they would soon be able to pick up the language in a country where English was universally spoken.

It is not clear how many Poles happened to be living in Christchurch in 1872, but if there were any, they did not seem to make themselves known to their countrymen. English employers quickly engaged 43 of the 61 single women, and local farmers snapped up 23 of the 33 single men. Only four of the 53 families found immediate employment in the new colony. Of the Polish families off the friedeburg, five others were from the same Ziemia Chelminska area of Prussian-partitioned Poland as the Grochowskis: Burchard, Gurni, Groskowski, Kotlowski, and Kurek.

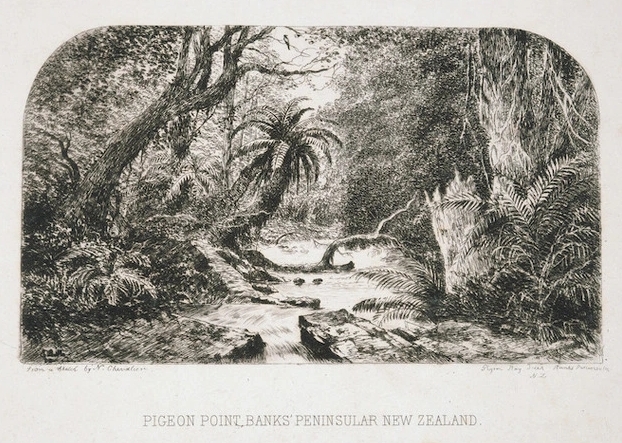

The Polish families gravitated towards Pigeon Bay and Holmes Bay on the Banks Peninsula, about 20 kilometres north of the French settlement of Akaroa. The area’s first British settlers, Messrs Hay and Sinclair, had arrived in 1843. Under the protection of colonial promoter Edward Gibbon Wakefield, they took up large tracts of land, cleared and developed enough of it to charter shipping vessels, and set up trade with Melbourne: their potatoes and cheese for livestock and other goods. They, and other settlers, felled the dense bush to trade in sawn timber, posts and rails, and firewood.7 George Holmes of Melbourne won the tender to create a rail tunnel through the side of the extinct volcano that stood between the Lyttelton port and the new town of Christchurch. He bought the Sinclair property, including the sawmill, and had the tunnel built by 1867.8

Around 1866 Nicholas Chevalier sketched this view up a stream at Pigeon Point on the Banks Peninsula. The two ponga ferns leaning into the stream will be familiar to New Zealanders, and the smaller palms in the foreground may be juvenile nikau, but the bird on the top branch is not instantly recognisable.9

English photographer Daniel Louis Mundy was apparently responsible for this scene looking over Pigeon Bay circa 1867–1869.10

The Poles’ arrival on the Banks Peninsula coincided with cocksfoot grass becoming “a more frequent component of cargoes leaving Akaroa.”11 An English nurseryman and seed merchant named William Wilson believed that he introduced the seed into Banks Peninsula in 1851, and that dairy farmers soon appreciated its superiority over ryegrass.12 That industry, which reached a peak in 1874,13 saved many of the Polish families from starvation. The good wages they earned in the harvesting season helped them through the earliest lean times, and to pay off the loans they had taken out from the government for their sea passages.

_______________

Simon Grochowski (25) and Francisca Tadajewska (22) married on 1 October 1868 at the Church of St Peter and St Paul in Lipinki in the Warmian-Masurian province of Poland. Then, it was known as the Conradswalde parish.

Simon’s mother, Marianna née Szczucka Grochowska. His father, August, who died in 1851, was apparently Marianna’s third husband. According to the Tadajewski family tree, Simon's only sibling, Josephina, died as an infant in 1848, and his mother in 1869. His mother's name, the same as Franciszka's dead sister's, suggests that Simon and Franciszka wanted the spelling of his daughter Mary Ann's name to be Marianna.14

Simon was an orphan with no siblings, but Franciszka was the fourth of eight children. Her mother, Marianna née Jeleniewska, had also died, but when Franciszka emigrated to New Zealand, she left behind her father, who had remarried, and five siblings who had survived into adulthood.15

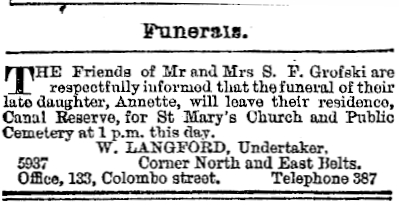

When the priest married Simon and Francisca, he germanised their first names, and retained the Polish spellings of their surnames. It was different in New Zealand: from the time they arrived in Lyttelton, their surname was subjected to an array of spellings and obfuscations. Annie’s funeral notice in March 1893—10 years after her father died—seems to be the first use of the spelling Grofski. Until then, other spellings included Crokowsky, Gerosky, Glogoski, Grahofski, Grofskey, Grofsky, Grogoski, Grokowska, Gronfsky, Gronkosski, Gronkouski, Gronkovsky, Gronkowski, Groschkowski, Grosenosky, Grosewski, Groshinski, Groskwsky, Grosrkowski, Groszkowski, Groufsky, Groukowski, Growchowski, Growszk, and Grojeski.16

In 1872, the natural confusion resulting from English-speaking officials and French or Irish priests transcribing Polish names, was not helped by the Groskowski family also on the friedeburg and who settled in the same area. To English ears in New Zealand, the two different surnames seemed the same.

By 1874, with the Lyttelton rail tunnel having eased Christchurch’s access to its port and therefore markets, speculators eyed the swamp north of the city. They bought the then-useless-for-farming blocks at bargain rates, and looked for people to lease and drain the sections. One of those speculators, Edward Reece, happened to find out about the Poles at Holmes Bay, and pursued their labour.17

Exactly how soon after 1874 the first Poles moved north and took up leases in the Marshland area is unclear. Those with cocksfoot seed collecting contracts on the Banks Peninsula would probably not have left their lucrative jobs before the harvest was over in autumn, around Eastertime in New Zealand.

Although the Poles off the friedeburg did first settle on the Banks Peninsula, it would be a stretch to assume that they lived and moved as a homogeneous unit. The Grochowskis were one of the few early Polish settlers who had no familial ties with other Poles in the new colony, and no potential for relatives from Prussian-partitioned Poland joining them after Franciszka’s father and four of her siblings moved to the USA in May 1874. The Grochowskis were not among the Poles who first moved north of Christchurch city. Perhaps when Reece’s offer came, Franciszka was still waiting for news from the family she had left behind, and was hoping they would join her?

_______________

Birth, marriage, and death certificates, and church records, in New Zealand trace the family’s movements, and show that they did move north for a time, but it was to Papanui, west of Marshland.

Franz Grochowski’s first sibling was Joseph Alfonsus. His death record at the Tūranga library, Christchurch, states that he was born in Akaroa in 1873. It is not clear under what surname his birth was registered.

Luigi was born on 10 October 1874. He was baptised at the Akaroa Roman Catholic church that Christmas Day, and recorded as Luigi Crocowsky.

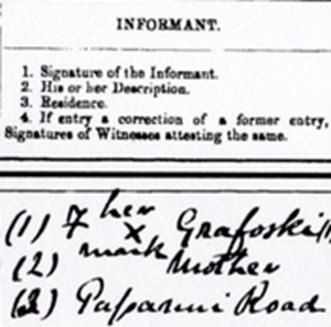

Mary Ann was born on 14 December 1875 while the family was living in Papanui Road, Christchurch.

According to family story, Bernard Joseph was born in Tai Tapu, on 21 October 1877, and baptised the following month as Bernard Growszk.

Alexander Robert was born in Tai Tapu on 15 February 1881 and baptised as Michael Alexander Grofskey.

Annie Paulina, who was born in Tai Tapu on 26 October 1882, was baptised with her older brother on 16 January 1883.

_______________

The lack of Poles as the children’s baptismal sponsors seems odd. Rebecca Mary Sweeny, Johanna Hofmaster, Catherine Pitt, and Mary O’Reilly were not obviously Polish, and neither were a Mr Cosgrove and Julia Ford, Bernard’s godparents. It suggests at face-value that the family did not often encounter the other Poles, or that there were no Poles at Mass on those particular baptismal Sundays.

Except that the Cathedral baptisms for the younger Grochowski children did not happen on Sundays, which perhaps explains why records use the word “sponsor” rather than “godmother” or “godfather.”

The reason why Bernard was the only sibling to have two godparents recorded may have been simply because the event happened on a Saturday, and there may have been more men around.

Alexander and Annie were baptised together on a Tuesday, which further indicates that the trip into the city was one not taken often, nor lightly. For families living far from the city, it seemed to be incumbent on the mothers to ensure that they were formally initiated into the wider Catholic community in Christchurch.

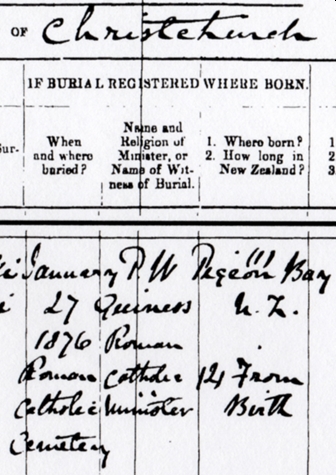

Franciszka registered her daughter Mary’s birth on the same day she registered the death of her 15-month-old son Luigi—26 January 1876—who had died the day before. The date happens to match that of Mary’s baptism, and was a Wednesday, which indicates her father’s absence was because he had either taken up work that caused him to lodge away from his family, or could not afford to take time off work. It was not unusual for early Polish settler families to have fathers work away from home for weeks at a time, and points to Simon then not being in a financial position to pay for a lease of land.

Luigi’s death certificate (as Simon Grafoski) shows that he was born in Pigeon Bay, that he died from diarrhoea and convulsions, that he had been suffering for seven days, and that a doctor JH Townend had seen him four days earlier. Franciszka put her mark on both certificates, but her illiteracy meant that she would not have realised that her just-dead son was mis-named Simon.

The certificate shows that Luigi was scheduled to be buried the next day by a Roman Catholic minister, PW Quiners, in a Roman Catholic cemetery whose name is illegible, or might be a generic “Roman” because the registrar could not have been sure of the place of something that had not yet happened. Papanui did not have its own parish until 1924, and in 1876 was serviced by what was to become the Cathedral Parish, which at that time had no priests whose names matched Quiners.18

The section of Luigi’s death registration showing that he was due to be buried the day after his death, but the place and minister remain a mystery.

Like her signature on any document, Franciszka signed her son Luigi’s death registration with her “mark.”

One explanation for Mary’s baptism occurring on the same day as her brother’s death registration may be linked to what caused Luigi’s death, the time of year, and the probably German sponsor on Mary’s baptism certificate: Fransiczka would have known that besides her five-week-old baby, her other two children, seven-year-old Franz, and three-year-old Joseph, might catch Luigi’s diarrhoea. There was also the reality that in a hot summer month, keeping a dead baby would not have been hygienic for anyone.

There was only one option for Franciszka on 26 January 1876. Staunch Catholic, sensible farmer’s daughter, practical wife, and loving mother, she would have arranged for someone to look after the older boys, wrapped up her dead infant, and taken him and Mary with her to the then Pro-Cathedral.19 The priest attending would have taken the infant to bury and baptised the baby. The name of Mary’s baptism sponsor, Johanna Hofmaster, seems German, but the priest may have known she could interpret for Franciszka, and give her instructions to then go to the Christchurch registry office at the Post Office building in Market Square (now Victoria Square), about a 30-minute walk away.20

If the registrar and Franciszka did not know the local priest well—Fr John Chareyre SM was posted to the Cathedral in 1875—and if Franciszka could not properly repeat his difficult name, the registrar, then a JW Parkerson, may have misinterpreted it. We know he saw baby Mary because he noted her presence.

All manner of computations of Luigi’s name and date of death in the Christchurch cemeteries database offer no clue as to where he may have been buried. His record may be one of those missing from Barbadoes Street cemetery.

Like his son, Simon Grochowski’s place of burial seven years later also remains a mystery. The mistakes on Luigi’s death certificate were compounded on his father’s. Despite acting as informant on Franciszka’s behalf, the agent James Weatherley clearly did not know the family.

Unless there were two men of the same name in the area, this one was probably the Constable James Weatherley who had been working for the Lincoln police for at least two years. His name appeared in the new zealand police gazette in April 1881 after he arrested a man for neglecting to support his wife. Franciszka would have met him when she went to the police station to report her husband’s death—or perhaps, with no medical attendant available, the constable was called to confirm the death.

In May 1883, a possible scenario at the registrar’s office:

“Name?”

“Tadajewska.” (Polish women expect to give their maiden names.)

The official wrote ‘Fadeifska.’

“First name?”

“Franciszka.”

Perhaps here, Weatherley intervened, and explained that the official was asking for her husband’s name.

“Simon.”

In death, after 11 years in New Zealand, Simon Grochowski died under the misspelling of his widow’s maiden name. The official and the agent clearly assumed that Franciszka had given her married surname, because it is repeated four times on the death certificate—as the surname of Simon’s father, the maiden name of his mother, and the name of the person he married. The certificate accurately listed the ages and genders of Simon’s six children, which shows that when Franciszka understood the questions being asked of her, she was able to answer. It is not clear who decided on cancer as the cause of death. Without a medical attendant, that assumption was “uncertified.”

The Roman Catholic Reverend JC Chervier (another spelling for “Chareyre”?) apparently witnessed Simon’s burial on 11 May 1883 at the Lincoln cemetery, but the whereabouts of his gravesite is unsolved.

_______________

Luigi’s death seemed to be the catalyst for the family’s return south of the city. The birth certificates of children born after Mary, and their father’s death certificate, put them in Tai Tapu.

Like Marshland, Tai Tapu, at the foot of the Port Hills, had its own share of flax- and raupō-covered swamp, but later became known for its fertility and fabulous dairy farms.21 The colonial farmers there bought hundreds of acres at a time, at prices way beyond what a labouring Polish immigrant could afford.

The Tai Tapu entry in the cyclopedia of new zealand22 lists 13 farms in the area. Descriptions of the land bought before 1881 repeat the words “heavy swamp” so often that there is no doubt about the state of the land where Simon Grochowski worked. The family story that he died from drinking contaminated water seems a viable hypothesis: There was enough boggy ground in the area at that time that any labourer would have struggled not to ingest the water while removing flaxes or raupō.

_______________

“Fanny Graskie”23 was again living in Papanui when she married Heinrich Behren at the registrar’s office in Christchurch on 17 July 1885.

According to their marriage certificate, Franciszka was a widow aged 31—she was 38—and Heinrich was a bachelor-labourer from Tai Tapu aged 32. JM Parkerson was still the registrar. His handwriting had deteriorated to such an extent that it is impossible to make out “Fanny’s” maiden name. The witnesses were William Brown, a farmer from Tai Tapu and what seems to have been a Julia Rodey of Rhodes Swamp. (She was Julia Roda, who was seven in 1874, when she arrived in Christchurch with her parents Albert and Marianna and younger brothers.)

Franciszka had no children with Heinrich, who seemed to embrace hers as his own. Judging from records, he made little effort to ensure they kept their father’s surname. Heinrich was also loose with the other information he gave to the schools, especially regarding birthdates, which were random and fluctuated by years, and addresses, which were vague.

School records show that after the marriage, the family gravitated towards Marshland.

By October 1886, they had moved from Papanui to New Brighton. That was when a Mr Behrens enrolled Bernard Behrens at the Burwood School.

In March 1887 Henry Behrens enrolled Alexander Behrens at the same school, and in August 1887, he enrolled Anne Behrens. Her last day at Burwood was in July 1881. She left apparently because the family moved to “Christchurch.” A year later and within days, Henry Behrens enrolled Annie Behrens, then Alex Behrens at Marshlands School. The family then lived in Marshland.

Alex apparently left the school in July 1893, when he would have been 12. Annie was taken off the books when she died three months prior.

Just six months after Mary died, 10-year-old Annie was admitted to Christchurch Hospital with diphtheria. She was dead within two days. On her death certificate, her father was recorded as Groffolski Behrtens. This name, the fact that the death registration was done through an agent, and the funeral notice (below) that appeared in the lyttelton times on 8 March 1893, points towards Heinrich Behren’s having left Franciszka and her family between Mary’s marriage on 26 November 1891 and Annie’s death on 6 March 1893.

In the funeral notice, “Mr and Mrs S.F. Grofski” could only refer to Simon and Franciszka.24 Annette was the family’s name for Annie. Her brother Francis, then 22, was the likely liaison between the family and the undertaker. He used the same surname spelling for his naturalisation as a farmer from Marshland a few months later.

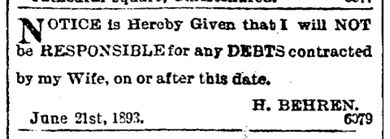

After all the apparent involvement with Franceszka’s children, it seems strange that Heinrich/Henry Behren/Behrens/Behrtens would desert Franciszka so soon after she had lost both her daughters and her first grandchild. But that is exactly what he did, and just months after Annie’s death, he took out an advertisement in the press:

An appearance at the Christchurch magisterial court in 1895 gave away his bolt-hole. The newspaper article on the event described Henry Behren as a “respectable farmer” from Tai Tapu, and made out that the fact that he stole “a jar and two gallons of sherry” was only because he had had a bit too much to drink one day.26

It is not clear exactly when Frances moved to Marshland, but she reverted to the name Grofski when she moved into the “primitive two-roomed house” near McSaveny’s Road that had been built by the loner Richard Boshen. Wilfred John Walter, who grew up in Marshland, wrote in his memoirs that “she and her family worked very hard on the place.”27

_______________

In July 1897, Franciszka began to mark family celebrations rather than sorrows: Francis Cyril Grofski married Mary Margaret Piekarska, the daughter of another of the friedeburg families who first sought work on the Banks Peninsula. She was born in Lincoln in September 1877. Baptism records show that the Piekarski family moved from Pigeon Bay to Springston, Rolleston, and Horseshoe Lake, New Brighton, before settling in Marshland around 1891.

Franciszka with her sons, from left: Frank (Francis), Bernard, Joseph, and Alexander.

Francis and Mary’s first child, Eva Mary Anne, lived for only 30 hours in 1898, but they had five more children: David Laurence, Eileen Mary, Eric James, Doris Maud, and Ethel Jane.

David was born in March 1900, just a month before his uncles Joseph and Alexander left Christchurch to serve as volunteers with the British Imperial troops still fighting in the South African [Boer] War. The brothers had consecutive regimental numbers in the 14 Canterbury Company of New Zealand’s Fifth Contingent. On their enlistment papers, both were described as farmers from Marshland. In its list of troops, the press gave Joseph’s address as Hills Road.28

Queen Victoria decided to reward her soldiers in South Africa with a box of chocolates each. The 123,000 rectangular tin lids had curved edges so that they would fit easily into the soldier’s packs. The lids showed her embossed portrait on a red background, her royal cypher VRI, the inscription “South Africa 1900” and her hand-written message, “I wish you a happy New Year.“ They became collectable items.

Newspapers filled column inches with news of the war and in October 1900, one mentioned that Joseph had been taken to Mafeking hospital.29 Although Franciszka was illiterate, she received news second-hand. When a “friend of a returned New Zealander” told her that Joseph had died of his wounds, and she had not heard from him nor Alexander, she feared the worst.

Francis was spurred to write to William Tanner, MP for Heathcote, to ask him to investigate on behalf of a “woman already in very poor health.”

“Imagine, Dear Sir, the poor old Mother’s feelings almost alone in the world already.”

The news about Joseph proved to be false. Both the brothers returned aboard the tagus in early July 1901. More than 200 Marshland residents gathered at a public reception for them, and another pair of Marshland brothers, the Langes.

Mr A Malcolm… on behalf of the public of the district, presented each of the troopers with a gold Maltese cross, suitably engraved. Trooper J Grofski, on behalf of himself and his comrades, responded. Trooper Tubman, one of the visiting troopers, recounted some of his experiences in South Africa, after which several patriotic songs were sung, and cheers given for the returned troopers. Dancing, games and other amusements were then kept up until a late hour.30

The Canterbury branch of the “Fighting Fifth“ continued to hold reunions to remember their time in South Africa, and voted for Joseph as chairman several times.31 The Veterans’ Association was still active in 1913, but was no doubt superseded by WWI.32

Troopers Joseph and Alexander Grofski both received the Queen’s South African War medal with clasps for the Transvaal, Orange Free State, Rhodesia, and the Cape Colony campaigns. Both also applied to keep their rifles “in good order” and promised to return them if called on to do so by the Defence Secretary in Wellington.33

In 1902, aged 28 and then living in Doyleston, Selwyn, Joseph filled out a form for another military commission where he described himself as being “a fair shot” and having “an imagination.” In answer to whether he was in “sound health,” he wrote, “Do not know what it is to be ill myself.”

_______________

Franciszka must have been satisfied in 1903 that her sons, then aged between 22 and 34, were well catered for, because she put up for auction all her stock, farming implements, crops still on the land, seed, and “a large quantity” of farming sundries as well as household furniture “and effects.”34

As Fanny Behren, she petitioned for a divorce from Heinrich Behren on the grounds that in 1892 he had “without just cause wilfully deserted” her.35 In her affidavit, dated 21 October 1902, she told the court that she had “from time to time” made inquiries as to his whereabouts, and had last seen him in Christchurch in January 1899. That meeting led to a stipendiary magistrate ordering Heinrich to pay maintenance, which he did for fewer than six months.36

Franciszka believed that rather than pay her, her deserter husband had left the colony.

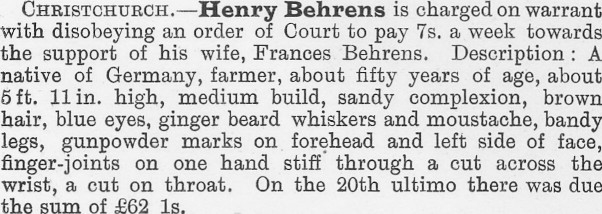

Henry Behrens’ description appeared in the new zealand police gazette in December 1902, under the section Deserting Wives and Families &c:37 (By then Constable James Weatherley of Lincoln, the agent who helped her to register Simon Grochowski’s death, was the Police Gaoler for Nelson.)38

An inconspicuous man may have been able to slip through various societies in New Zealand at the time, but “Henry Behrens” had some definite characteristics and blemishes. The police gazette’s many lists and mentions of rewards for officers of the law who apprehended felons and secured convictions suggests that they would almost certainly have been able to find someone with Henry Behrens’ ginger beard, bandy legs, and scars if he was still in New Zealand.

Francizka’s upcoming marriage to Deidrich Arps must have spurred her into action, because four days after she received her decree absolute on 25 July 1903, she married the 60-year-old widower farmer from Hallswell.

According to her marriage certificate, she was 54. One of the witnesses at the Christchurch registrar’s office was Mary “Sharlock” of Marshland, who signed with her mark. It is likely that she was Mary née Gearschewski Sharlick, the niece of friedeburg passengers Jan and Rozalia Gearschewski.39 Mary’s husband, Michael Sharlick, arrived in Lyttelton in 1883 with his brother, Michael, mother, Louisa, her second husband, Christopher Schimanski, and their children.

There is no doubt that Franciszka and her third husband would have known each other for many years: The Marshland memoir writer WJ Walter recalled that Deidrich Arps, one of the first settlers to the area, lived on the corner of Preston’s Road and Canal Reserve, less than a kilometre away from McSaveney’s Road. The eldest of the surviving 13 Arps children were the same age as the Grofski brothers. Several other early Polish settlers lived on or around Canal Reserve, which later became Marshlands Road.40

Deidrich Arps, too, had had his share of misfortune and deaths of children that culminated with the death of his wife, Elizabeth, in 1899. When he and Franciszka married, his youngest four children were aged between eight and 16 years. Judging from the 1905–1906 electoral roll, at least for their first years of marriage, Franciszka and Diedrich lived in Quifes Road, Halswell.

By the time Franciszka died on 3 April 1912, they had moved to Hills Road, Heathcote Valley. Her death notice described her as the “dearly beloved wife of Deidrich Arps.”41 A year later, her “loving husband and step-daughter” inserted the same memorial message in the press, the lyttelton times and the star: “Gone but not forgotten. May the Lord have mercy on her soul.”42

Franciszka was buried at the Linwood cemetery as Frances Arps, but her family has made sure her headstone bears the name she was known as within the Christchurch community, with an additional middle name: Frances Gabrielle Grofski. Deidrich lived to be 95, and is buried with his first wife and their three children who died young, at the St Paul’s Anglican graveyard in Papanui.

Her descendants have made sure that Franciszka née Tadajewska Grochowska Behren Arps now rests in the Linwood cemetery under the name she was best known: Frances Grofski. Her grave is at the end of a row in block 44, sheltered by a marcrocarpa, and is less than 20 metres away from her eldest child, Francis.

Francis Grofski outlived his mother by only three years. His widow, Mary née Piekarska Grofski, died in 1925, and lies with him in the Linwood cemetery.

_______________

Joseph Alfonso Grofski married Mary Anne Byrne in 1905. They had four children, Santella Claudia, Marianne Frances, Bryan Joseph, and Noelle Frances. According to school records, they lived in Gresford Street, St Albans, and the siblings attended St Mary’s School in Colombo Street.

Bryan followed his father into military service. He was a flight sergeant in the Royal New Zealand Air Force, and died in Palestine in 1942, aged 29. Joseph died aged 85 in 1958, and is buried at the Ruru Lawn cemetery with his wife, who died in 1951.

Bernard Joseph Grofski left Christchurch to become a warder at the Hokitika Mental Hospital. While there, he met Martha Elizabeth Jamison, who came from Arahura, a few kilometres north of the town. He took up a position at the Mount View Mental hospital in Wellington in 1909, and returned to Hokitika the same year to marry Martha. According to the west coast times, the couple took the evening train to Christchurch on their way back to Wellington.43

It is not clear where their first child, Martha Bernice, was born in 1910, but Bernard and his wife were in Christchurch for the birth of their second, Ida Frances, in 1913. When Martha started school, the family lived in Highsted Street, Harewood. The other four children were Bernard Terence, Annette Joyce, Adrian, who lived for only a few hours, and Kevin Alexander.

Bernard took up fruit farming in Papanui. He died in September 1944, and is buried at the Waimairi cemetery with his wife, who died in 1956.

Alexander Robert Grofski married another Byrne sister—Katherine—in 1910. Katherine’s sister Elizabeth was living with them in Lyttelton Street, Spreydon, when she drowned in 1912.44 Alexander and Katherine had two children, Denzel Alexander, and Muriel Katherine.

The family moved to Taranaki and lived in Inglewood. Alexander died in 1953, and is buried at the Inglewood cemetery with his wife, who died in 1962. Denzel died in 1977, and is buried at the Waitara cemetery. Muriel married twice and last lived in New Plymouth. She is buried under the name Muriel Eriksson at the Awanui cemetery.

_______________

As Simon and Franciszka’s direct descendants continued to grow in number, one of their in-laws wanted to make sure her Grofski daughters and granddaughter knew from whom they came. Daphne-Anne Freeke compiled franciszka’s story; 1847–1912 in 2012:

For my girls… This is your Polish heritage. Being Polish is not being born in a particular place at a particular time. It is belonging to a race of people from a country whose boundaries have changed as the countryside has been decimated by wars, and who despite this, have remained Polish.

Polish people have bravely journeyed to far flung ends of the earth to start a new life and continue their proud heritage. Franciszka’s story is but a glimpse through a small window in time. She did not make history, not will she be remembered by anyone other than her family, but her story is still inspirational.

Be proud that she is your ancestor and of the heritage that she has left you.

_______________

© Barbara Scrivens, June 2022

ENDNOTES:

All newspaper references from Papers Past, through the National Library of New Zealand, Creative Commons licence New Zealand BY-NC-SA

- 1 - Lynwood cemetery plan, block 37, map 2, thanks to Christchurch City Libraries/ Ngā

Kete Wānanga-o-Ōtutahi,

https://canterburystories.nz/collections/maps-plans/cemeteries/linwoodcemetery/ccl-cs-17332 - 2 - Thanks to permission from Daphne-Anne Freeke, who wrote Franciszka’s Story 1847-1912.

- 3 - Thanks to Triona Doocey, Archivist at the Catholic Diocese of Christchurch.

- 4 - Intentions to Marry 1891, Line 7259,

https://assets.ctfassets.net › Intentions_to_Marry_1891 - 5 - 2018 article by Alexandra Gilbert on behalf of the Friends of Linwood Cemetery for the website Kete

Christchurch:

http://ketechristchurch.peoplesnetworknz.info/site/topics/show/2070-still-born-children-in-linwood-cemetery - 6 - The Star, 2 September 1872, page 3, IMMIGRANTS BY THE FRIEDEBURG

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/TS18720902.2.9 - 7 - From the NZ Electronic Text Collection, NZETC, The Cyclopedia of NZ (Canterbury Provincial District), https://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-Cyc03Cycl-t1-body1-d5-d12.html#:~:text=Pigeon%20Bay%20is%20one%20of,inland%20from%20Pigeon%20Bay%20heads.

- 8 - More on the tunnel from Engineering New Zealand, Te Ao Rangahau,

https://www.engineeringnz.org/programmes/heritage/heritage-records/lyttelton-railway-tunnel/ - 9 - Chevalier, Nicholas, 1828-1902. [Chevalier, Nicholas] 1828-1902 :Pigeon Point, Banks' Peninsular, New Zealand / from a sketch by N Chevalier [1866?]. Ref: B-051-002. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/22347782

- 10 - Pigeon Bay, Banks Peninsula, New Zealand. Parliamentary Library: Photograph albums. Ref: PA1-f-186-19-2. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/23187116

- 11 - Article from the New Zealand Grain & Seed Trade Association (NZGSTA). The article does not have an author

nor a heading:

https://www.nzgsta.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/history/History-of-Cocksfoot-Banks-Peninsula.pdf - 12 - The Press, 30 January 1895, page 3, BRIEF HISTORY OF THE COCKSFOOT,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/CHP18950130.2.9.6 - 13 - Ibid NZGSTA

- 14 - Portal Rodziny Tadajewskich

https://www.tadajewskifamily.com - 15 - Ibid, Linia 13.

- 16 - Name spellings from Daphne-Anne Freeke, and list of baptisms in the Christchurch Catholic Diocese before 30 June 1908.

- 17 - For more on the first Poles who settled in Marshland from 1874, see Marshland: The Place Where Flax Grows

Profusely,

https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/marshland/ - 18 - Ibid, Triona Doocey.

- 19 - Thanks to Library Enquiries Tuakiri for the link to the old Cathedral being removed in 1900:

Removal of the Roman Catholic Pro-Cathedral, Christchurch: [1900] - Christchurch City Libraries Heritage Photograph Collection. - 20 - Information from Library Enquiries Tuakiri.

- 21 - The New Zealand Electronic Text Collection, Tai Tapu,

https://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-Cyc03Cycl-t1-body1-d6-d8.html - 22 - Ibid.

- 23 - The name on her 1885 marriage certificate.

- 24 - The Lyttelton Times, 8 March 1883, page 1, Advertisements Column 1,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/LT18930308.2.3.1 - 25 - The Press, 22 June 1893, page 1, Advertisements Column 4,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/CHP18930622.2.3.4 - 26 - The Star (Christchurch), 3 December 1895, page 3, MAGISTERIAL,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/TS18951203.2.39 - 27 - WJ Walter collection held at the Christchurch Archives, Archive no. 196, pages 15&16.

- 28 - The Press, 24 March 1900, page 8, THE FIFTH CONTINGENT,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/CHP19000324.2.47 - 29 - The Press, 13 October 1900. Page 8, WITH THE FIFTH CONTINGENT,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/CHP19001013.2.39.29 - 30 - The Lyttelton Times, 30 July 1901, page 5, THE WAR IN SOUTH AFRICA,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/LT19010730.2.67 - 31 - The Lyttelton Times, 7 May 1906, page 6, TOWN AND COUNTRY,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/LT19060507.2.35 - 32 - The Lyttelton Times, 25 January 1913, page 9, VETERANS’ ASSOCIATION,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/LT19130125.2.43 - 33 - Joseph: https://ndhadeliver.natlib.govt.nz/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=IE24475317

Alexander: https://ndhadeliver.natlib.govt.nz/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=IE24474943 - 34 - The Press, 27 May 1903, page 12, Advertisements column 1,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/CHP19030527.2.72.1 - 35 - The Lyttelton Times 21 February 1903, Page 11, Advertisements Column 7,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/LT19030221.2.106.7 - 36 - Thanks to Anna Gruczyńska for viewing Franciszka’s divorce papers at the Christchurch archives.

- 37 - New Zealand Police Gazette, Volume XXVI, Issue 26, 17 December 1902, page 291, Deserting Wives and

Families &c.

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/periodicals/NZPG19021217.2.6 - 38 - New Zealand Police Gazette, Volume XXVI, Issue 13, 18 June 1902, page 159, Extracts from New Zealand Gazette, https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/periodicals/NZPG19020618.2.10

- 39 - This family also had several versions of their Polish name, Gierszewski, in New Zealand.

- 40 - For more on Marshland, WJ Walter’s memoirs, and where the Grofski family fits in with the other Marshland Poles

see:

https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/marshland/ - 41 - The Lyttelton Times, 4 April 1912, page 1, DEATHS,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/LT19120404.2.2.3 - 42 - All the messages appeared on 3 April 1913, IN MEMORIAM,

The Press, page 1: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/CHP19130403.2.2.2

The Lyttelton Times, page 1: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/LT19130403.2.2.3

The Star (Christchurch) , page 3: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/TS19130403.2.35

- 43 - The West Coast Times, 15 March 1909, page 3, A PRETTY WEDDING,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/WCT19090315.2.8 - 44 - The Star (Christchurch), 19 June 1912, page 3, ACCIDENTS AND FATALITIES,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/TS19120619.2.53