The Palenski Family

by Ron Palenski, great-grandson of Henry and Annie Palenski.

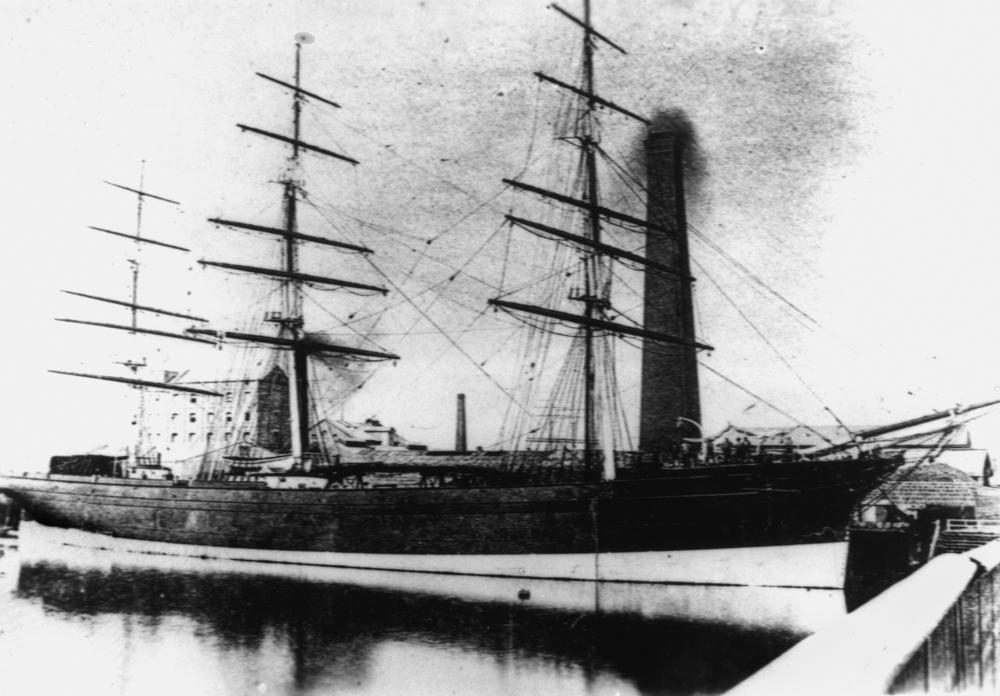

More than 400 would-be immigrants waited and waited on the Scottish-built three-masted sailing ship, the fritz reuter, tied up in Hamburg in the late European winter of 1875-76. They had been promised a better life in far-off New Zealand—a fledgling country they’d probably never previously heard of—by William Kirchner, an immigration agent.

Sixty per cent of the immigrants were ethnically Polish from Pomerania on the shores of the Baltic. The north of Poland had been annexed in 1864 by Prussia, which was ruled by Otto von Bismarck, who was on his way to creating a unified German state. Bismarck didn’t like the Poles, who were not German or Prussian. In some areas, including Pomerania, the teaching of Polish in schools was forbidden, some names were “Germanised” and some Polish names had to forcibly remove the suffix “ski.” The Poles still had their uses though, because military service for Prussia became compulsory.

Kirchner’s promise of freedom in a new land would have come like a siren’s call to the people of Pomerania, even if it meant leaving everything they knew for something they knew not at all.

The reason the ship and the immigrants on board waited and waited in Hamburg was that the New Zealand government, which had begun the mass immigration programme, decided it had enough people for the time being and assisted passages had to stop. Kirchner protested to his immediate boss, the New Zealand agent-general (forerunner of high commissioner) in London, Isaac Featherston, that he could not stop because he had a shipload of immigrants waiting to sail. Featherston died before the impasse was resolved but his replacement, William Tyrone Power, was of the same view.

Undeterred, Kirchner dispatched the ship southwards anyway, figuring that by the time it arrived in Wellington, the government would have to pay for the passage of the people on board. Kirchner’s resolve was aided by the Prussian government, which told him the ship had to go.1 While the fritz reuter was waiting at the Hamburg wharf, some of its would-be passengers tired of the stalemate and moved to another ship, the humboldt, and went to Brazil instead.

Among the emigrants who stayed on the fritz reuter were Henryk Palenski, 32, his wife, Auguste, 31, and their two sons, three-year-old Theodore Henryk and Arnold Karl Herman, 18 months. Henryk (also Heinrich in the Bismarckian way and Henry or Harry in the New Zealand way) and Auguste (nee Meissen; sometimes given as Augusta, who was known as Annie) had been married on September 27, 1868 and they came from the rural town of Sassin.

The ship left Hamburg on April 12, 1876 and arrived in Wellington on August 4. Of the 425 emigrants on board, 259 were Polish. The general health of all the passengers during the voyage was said to be excellent; “only” 11 deaths occurred—one adult, four children and six infants under 12 months old.2

The fritz reuter was anchored in Wellington harbour while government officials decided what to do, since the immigrants on board were not official. After about a week, when food and water on board was running out, the government on humanitarian grounds allowed the passengers to land. They were initially processed on Somes Island and the Poles were recorded as being Germans, which would not have pleased them. Once they were landed, the Poles rushed the office of the shipping agent, Messrs Krull and Co, to exchange their German money for English (no New Zealand currency then). According to the post, the Poles had “a weighty mass of coin” and received about 19 shillings for gold 20-mark pieces.3

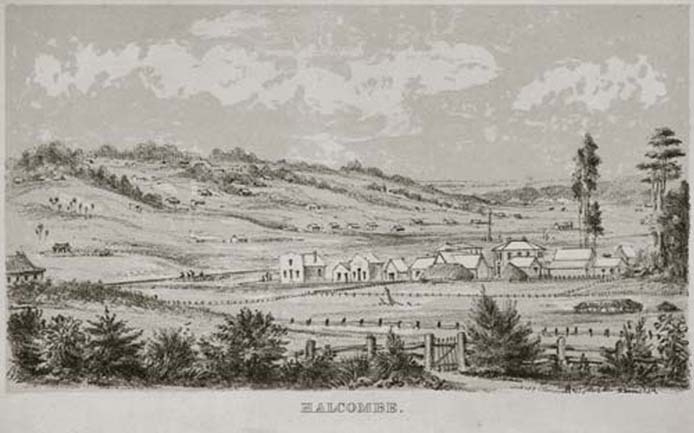

Most of the Poles were allocated settlement at Jackson’s Bay and Hokitika or Taranaki. Eight days after the arrival of the fritz reuter, Arthur Halcombe, who acted for owners and developers of land in Manawatu, arrived in Wellington. He selected about 60 of the immigrants to take with him by steamer to Foxton and thereafter inland by the newly laid railway line to the area of what became known as Halcombe.4 Among those selected for Halcombe was the Palenski family. They were taken first to a depot in Palmerston North and then a day or so later by horse and wagon to Halcombe. As one later report said: “Ready and waiting for the settlers were new one-bedroom houses each built on an acre of land. Settlers were entitled to ownership of the property, provided that they met their rental payment for the first three years of occupancy.” 5

The Palenskis thus settled in and around Halcombe and its bigger neighbours, Feilding and Palmerston North, strangers in a strange land. Henryk Palenski became a naturalised New Zealander (and, therefore, according to the practice at the time, a British subject) on September 27, 1890, just over 14 years after arriving in New Zealand. He did not long remain after that, however. By this time they had three more children: August (Albert or Angus) Edward Robert, born in 1877; Agnes Ada Malida (Molita), born in 1879; and Eda Mary Florence, born in 1887. There also appears to have been an infant who died when a year old. In Annie’s burial plot at the cemetery in Halcombe there is also a T G Palensky, aged one, interred on November 20, 1884. Both birth and death records have proved elusive.

Henryk and a friend from the fritz reuter days, Martin Bielski, were offered land at a new development at Rangiwahia, in the Ruahine ranges about 60km north of Feilding. Both paid deposits but the treasurer for the developing company absconded with the money to San Francisco. The remaining developers told the settlers they would need to forfeit the land or pay again. Bielski did, but Palenski couldn’t afford to. When time came to survey the new land, Palenski moved up from Halcombe to help peg out the area. There was another dispute with the developer, one Daniel Ritzman, a German settler, over whether the survey had been accurate. Bielski took Ritzman to court but his old friend, Henryk Palenski, apparently testified on Ritzman’s behalf, saying the work was not done well. Bielski had to move back to Halcombe.6

In October of 1892, Annie applied to the Magistrate’s Court in Feilding for a protection and prohibition order against her husband and also sought the custody of their two youngest children, 12-year-old Agnes and five-year-old Eda, and an allowance for Eda. Annie told the court that her husband “had frequently ill used her and beaten her when in drink.” Henryk had not lived with his wife since the last time he struck her a fortnight before.7 A woman identified only as “Mrs Clare” told the court she had seen “discolourations” on Annie’s face. She had not seen Henryk “in drink, but his actions are very often those of a drunken man.”

There was no objection to an order being made so it was granted and Annie was allowed 7s 6d a week toward the support of Eda. The court also heard that Annie owned property in Halcombe consisting of one acre and a house worth about £20, but she was not aware “there are 20 acres of land in Halcombe standing in her name.”

The Ritzman case resurfaced in 1896 when Ritzman sued Annie and her first son, Theodore Henry, over an unresolved land issue. It was during this hearing, in the Supreme Court in Wanganui, that it was stated Henryk had left New Zealand “in or about the year 1892.” It was said he left for America “and the plaintiff believes he is still and likely to remain out of the colony…” 8

Three years later, Annie was dead. At about 7.30 on the night of Thursday, December 21, 1899, her house in Halcombe was seen to be in flames. Annie had left her home, according to a newspaper report, to go to the railway station to meet a daughter returning from Marton. She arrived home to see the house on fire and a neighbour, Alex Williamson, tried to prevent her from entering but she broke away from him and ran into the burning building. A Mr Fromont followed her into the house and found her overcome by smoke and flames. He too was badly burned and he told another neighbour, Carl Wapp, where she was and he dragged her out. “Mrs Palensky was found to be very badly burned about the hands, arms, head and shoulders,” the wanganui herald reported. She died the next day.

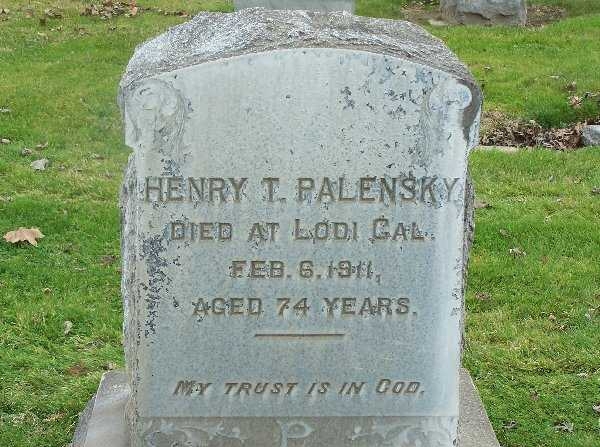

Her estranged husband had made his way to the grape-growing town of Lodi in California, where he died on February 6, 1911.9 It is not known why he went there, but perhaps he had an idea that rural workers from Pomerania were in the area. It’s only in recent years that the descendants learned what happened to their New Zealand patriarch. A newspaper report of his death described him as a Lodi pioneer, spoke fondly of him and said he was known as “Dutch Henry.”

© Ron Palenski, 2016

ENDNOTES:

- 1 - The saga of the Fritz Reuter is dealt with in EMIGRATION TO NEW ZEALAND (LETTERS FROM THE AGENT-GENERAL), Appendix to the Journals of the House of Representatives, D2, 1877.

- 2 - Evening Post, August 5, 1876, page 2. Papers Past, through the National Library of New Zealand.

- 3 - Ibid, August 9, 1876, page 2.

- 4 - Ibid, August 12, 1876, page 2.

- 5 - Fay Bagnato, The Promise of Work and a New Life—The Story of the Bielskis of Rangiwahia, Manawatu Journal of History, issue 2, 2006, page 69. (Fay's story reproduced on this page.)

- 6 - Ibid.

- 7 - Feilding Star, October 8, 1892, page 8. Papers Past, through the National Library of New Zealand.

- 8 - Wanganui Herald, October 8, 1896, page 2. Papers Past, through the National Library of New Zealand.

- 9 - Photograph by Denise Steinert Gordon, at the Lodi Memorial Cemetery, San Joaquin County, California.