Marshland

For thousands of years, it inhaled a forest and covered the evidence with flax, reeds, and grasses lightweight enough to survive among its boggy pools.

Early Māori respected the swamp’s hunger. They harvested the flora and fauna, but avoided crossing it directly. When they needed to travel along this stretch of Canterbury’s coastal lowlands, they took higher paths.

The Marshland swamp emerged from its specific geographical position within that coastline: The Banks Peninsula to the south of Christchurch trapped the fine sand and siltstone that the Waimakariri river, about 20 kilometres north of the city, brought down from the eroding Southern Alps.

Floods, currents, and tides rearranged the mountainous sediment with the detritus it encountered. Tidal flats emerged, then peat-rich bogs resting on clay “stretch[ed] out as tongues into the swamp and sandhill complex.”1

By the time the first four ships carrying British settlers arrived in Canterbury in 1850, the sand dunes parallel to the Christchurch coast ran higher than the peat-swamps they contained.

The newcomers who disembarked at Christchurch’s port, Lyttelton, on the northern edge of the Banks Peninsula, had little interest in the swamp—but once the city grew, speculators saw potential in an area close to a ready and growing market.

The swamp resisted being tamed.

Descriptions of Marshland in the 1870s and 1880s paint similar versions of the same story: People pitched against an unknown and unrelenting environment.

The first large group of Polish settlers to New Zealand sailed on the friedeburg and arrived in Lyttelton on 30 August 1872. They did not get to Marshland until 1874, when Poles off ships such as the cartvale joined them.

Official spellings of early Polish names were often inventive, but English street names in this suburb sometimes changed completely, and more than once. I have used the Christchurch City Libraries’ list of current street names, and their histories.2 Nowadays most have lost the possessive punctuation.

I wrote the first version of this story in 2017. Several new family stories have since joined those in the menu on the left. Those involved with Marshland include WJ Boloski, the Dodunski-Schimanski family, Rosalia Gierszewski, the Grofski (Grochowski) family, the Neustrowski-Watemburg family, Mary Watembach la Vavaseur, Martin Sharlik, and the three extra pieces on the Schimanski family.

A list of the Poles aboard the friedeburg is included in the story polish anchors 1872–1876 and they appear in more detail in the list of early polish settlers under that ship’s name.

Pinning down credible histories from so long ago is tough, and I am grateful for the collaboration of family genealogists. If anyone would like to contribute a family story, or discuss something I have written, please get in touch with me through our home page.

—Barbara Scrivens

THE PLACE WHERE FLAX GROWS PROFUSELY

by Barbara Scrivens

Although Marshland be a swampy place,

And in it stumpy ground,

Men of understanding good,

Are therein to be found.3

“Men of understanding good” understates the mettle of Marshland’s pioneers who, when they first took on leases for the boggy land in the 1870s, did not know about its power to engulf horses, cattle, and sheep—or the occasional unwary human.

The flax and reeds growing through the pools of water hid an underground secret: The drained land exposed buried kahikatea (Dacrycarpus dacrydioides), mataī (Prumnopitys taxifolia), ribbonwood (Plagianthus regius) and an occasional totara (Podocarpus totara). Semi-petrified mānuka (Leptospermum scoparium) lay a metre below the surface.

A Christchurch Teachers Training College student, Hywel Wynn Hughes, wrote in his 1939 thesis, marshland: a social survey of a new zealand rural community, that long before Māori arrival, the area had already become so swampy, “even trees like the white pine [kahikatea] could not maintain themselves in the presence of so much water.”4

Hughes postulated that the first European settlers in Canterbury in 1850 would have looked on the “extensive low lying swamp area broken only by an occasional marine dune… [as] an abode fit only for the bittern…5

Compared with the fertility of the rolling plains which stretched westwards to the lofty foot hills of the Southern Alps a waste of impenetrable swamp and shifting dunes could have held little attraction… as far as the possibilities of settlement were concerned. The only means of crossing the swamp would be to follow one of the higher sand dunes which lie parallel with the sea and the very nature of those would make transport and in fact any movement at all, laborious if not difficult.6

Wilfred John Walter, whose family moved to Marshland in 1882, when he was four, devoted his life to local politics and wrote a memoir of Marshland’s beginnings:

The early settlers who blazed the trail were men and women of stout heart and great willpower… people of grit and ambition… They endured hardships, lived humble, simple lives… they kept plodding on until the land produced some crop, and as the years passed by, they kept progressing and improving their positions… what a transformation… in the appearance of the district after ten and twenty years of pioneering work.7

Walter named 112 families who settled, worked, and moved around the area as they first leased, then bought, land as it became available freehold. His memoir does not seem to be dated but from 1937 to when he died in 1946, he interviewed at least 10 children of the first settlers.

His papers are held at the Christchurch City Archives. They include parts of Hughes’ study, which Walter acknowledged as the work of a “young teacher who started this thesis in the 1930s… killed in World War II.” It is not clear whether the two ever met or collaborated, or whether Hughes’ work encouraged Walter to put a human face to the teacher’s descriptions.

The new zealand gazette April 1940 supplement listed Hughes as holding a primary school teacher’s certificate, A-grade, meaning that he qualified 31 December 1939. He had been assigned to teach at a “Native” school.8

Hughes never got the chance to follow-up on his work in Marshland. He joined the New Zealand Division of the Royal Navy on 18 December 1940 and, aged 22, was shipped out on the ss rimutaka as part of New Zealand’s Scheme B for tertiary-educated men to be trained as officers. Temporary Sub-Lieutenant Hywel Wynn Hughes was declared missing presumed dead after his torpedo boat, mtb308, was sunk in the Mediterranean by Italians on 14 September 1942.9

_______________

When Walter spoke of the “early settlers” he was not referring to the speculators who first laid claim to the swamp in the 1850s and 1860s, but to the families like his own, many of whom had arrived in New Zealand as farm labourers, carpenters, blacksmiths, and domestic servants:

The land was really the remains of a dead forest. So dense were the stumps that it was impossible to plough the soil without first stumping the land, and it was a sight to see the big stacks of timber… used as firewood and for fencing posts. Some logs lying on the surface measured as long as 40 feet.10

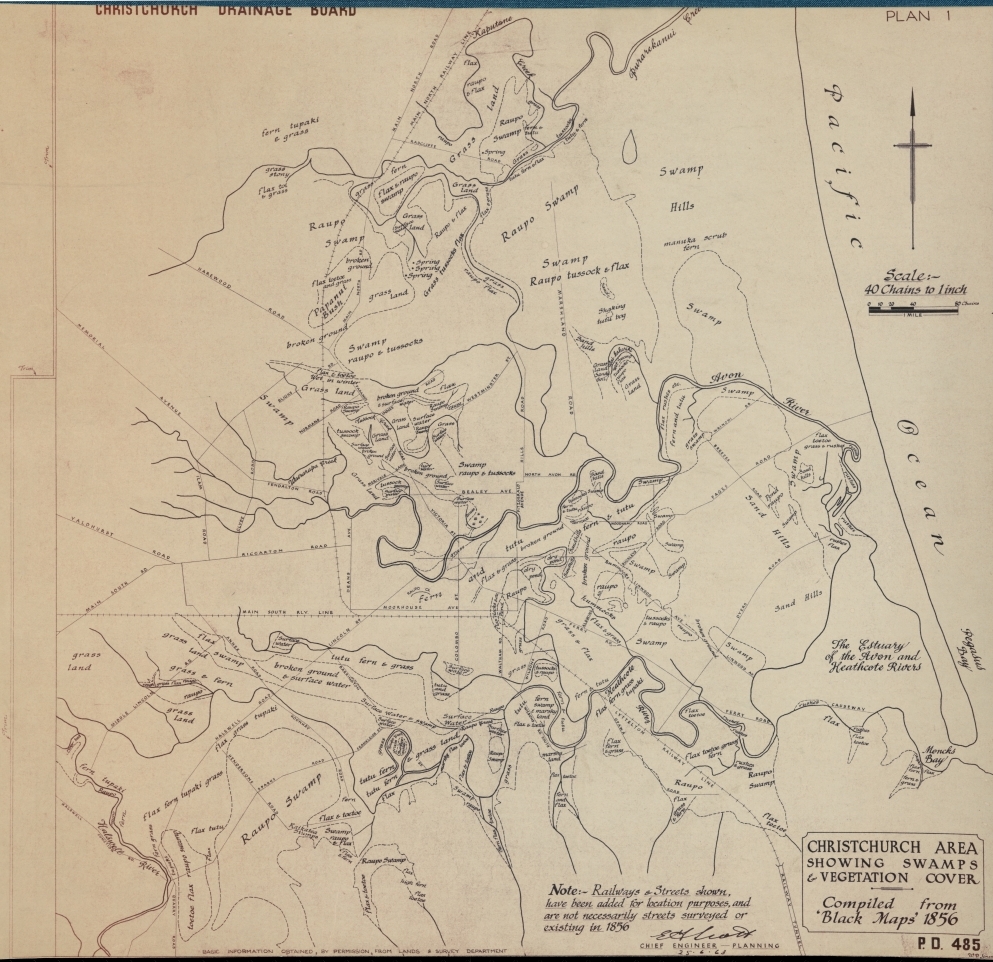

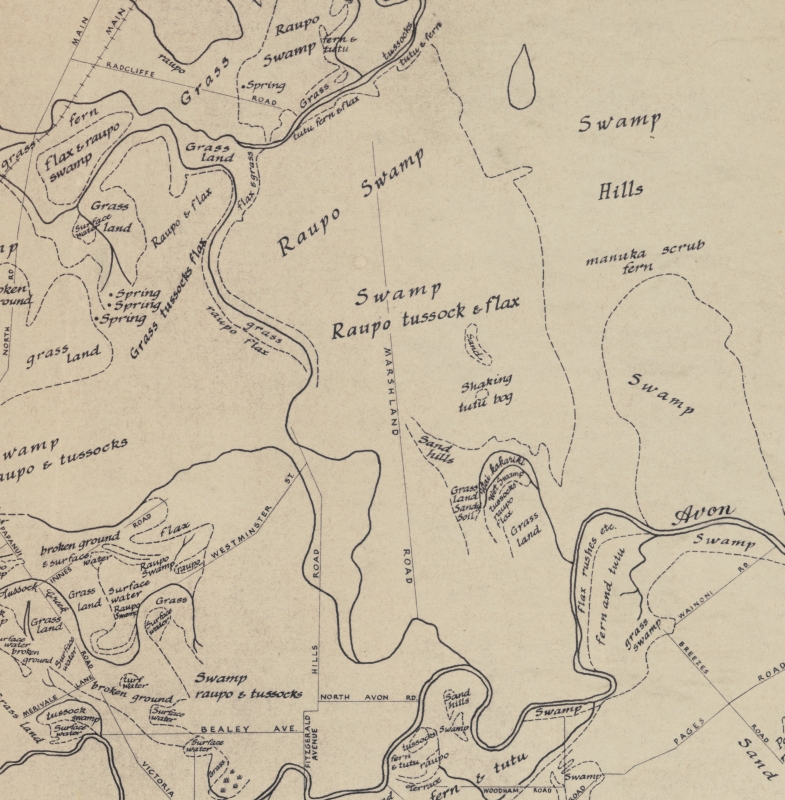

Christchurch’s Chief Engineer, Planning, noted in 1863 that railways and streets had been added to this 1856 map, showing Christchurch’s swamps and vegetation, and originally compiled by Ken Silby for the Christchurch Drainage Board.11

A close-up of the large raupō swamp that became Marshland. Marshland Road runs straight through the middle, from an Avon river tributary in Shirley, south, towards the “Purarekanui [Puharakekenui] Creek” (Styx River), north. The beginning of the dog-leg on Hill’s Road, then south-west of Marshland Road, eventually extended to form the western boundary of the swamp.

GNS Science, commissioned by Environment Canterbury in 2007, used this 1856 map in their analysis of Christchurch’s surface features before urbanisation. Then, the future city’s “wet features” covered slightly more than its “dry features,” 130 compared with 127 square kilometres. Swamp land contributed 54 square kilometres of the “wet.”12

Māori appreciated the Marshland swamp’s flax, wild fowl, eels, and, near the sea, its whitebait.13 They used the swamp as a source of food, medication, and useful household items such as bandages, fishing nets, traps, and baskets, but did not settle there, so what made Christchurch’s British forebears decide that colonial settlers could tame the land?

The first Europeans saw Māori camping on the corner of Canal Reserve (Marshland Road) and Hawken’s (now Hawkins) Road and catching “large hauls of eels” in the Styx river. The Māori left via the old terraced inland track that evolved into the first Hawken’s and Hill’s roads, and avoided the Canal Reserve, then “impossible” to negotiate thanks to bogs, springs, and flax.14

That inland track followed Marshland’s highest contours and its highest point, 17 metres above sea level, was on the corner of Hill’s and Preston’s roads.

Marshland lay just 10 kilometres from an expanding central Christchurch. As the families from the 1850s’ first four ships15 grew, and other immigrants followed, so did the market for food. Ten years later, speculators explored the possibility of draining the swamp and making use of it as agricultural land.

What was that land worth? Who would buy a swamp?

_______________

The 1850 settlers had been specially recruited by the Canterbury Association to establish an Anglican Church in New Zealand. Hughes described their settlement as the “best example of an existing expression of the Wakefield doctrine,” which New Zealand coloniser Edward Gibbon Wakefield crafted for the moneyed elite in Britain. Wakefield did not want the lower classes to buy land and pushed to prevent what he called a “squatting system which permitted the renting of large areas cheaply for grazing stock on native pastures.”16

Wakefield had been ‘buying’ land from Māori and selling it to colonial settlers since 1840. He developed a notion that immigrants without capital should not become “instant” landowners. “Sufficient price” became the standard he used to decide the value of colonial “waste” land, and restrict its sale. The strategy was meant to restrict the sale of land, prevent mere labourers from becoming “proprietors” and encourage more of those labourers to immigrate to the colony by giving them passage “free of charge.”17

The Canterbury Association, under its leader and founder, John Robert Godley, followed Wakefield’s doctrine and its regulations on the sale of land. Godley believed Canterbury’s 1850 immigrants “ensured” that “men of capital” would “form an aristocracy.” The policy left labourers to work for those “men of capital” and to save for years to buy “small parcels” of their own land.18

Wakefield’s “men of capital,” however, were reluctant to part with their money. After a year, they had contributed only ₤50,000 of the ₤500,000 Godley expected them to invest, which led directly to a lack of funding for the “most necessary public works.”19

At first, land cost ₤3 an acre, whether it was in Lyttelton, the Banks Peninsula, the Canterbury foothills—or the coastal swamp.

The sale of swampland inevitably lagged behind land more easily developed, although Canal Reserve (now Marshland Road) between the Avon and Styx rivers became part of the water-logged city’s early plans to develop a canal transport system based on England’s. The idea evaporated with the water.

Before he left New Zealand in December 1853, Godley trieded to boost growth in Canterbury by enticing the “men of capital” with an amended land policy—one that allowed Christchurch’s “waste” lands to be taken up in “Class III runs” in lots of between 5,000 and 50,000 acres.20

Under the new scheme, a “man of capital” applied for a so-called run at the Land Office. If there was no prior claim, the Land Waste Board allowed him the use of the land for a farthing an acre for two years, a half–penny for the next two years, and three farthings an acre thereafter. That person had six months to stock the property, meet the conditions, and retain a pre-emptive right to buy it.21

Although Marshland’s swamp discouraged potential freeholders willing to pay the ₤3 an acre, the new policy tempted speculators with a clause that permitted the leasehold of five acres of pastoral land for every acre of freehold. And so Marshland—too labour-hungry to remain in large estates—managed to frustrate some of Wakefield’s and Godley’s capitalistic aspirations.22

In 1852, a “dairy station” was established on two runs between the southern Canal Reserve and Avon river, and started supplying Christchurch with milk. Immediately north of the dairy startion, Marshland’s first two runs on either side of Canal Reserve Road were bought in 1853 by a Doctor Moore, who took up Sand Hills on the eastern seaward side, and in January 1854, by Charles Fooks, who took up the western inland side.23

By 1863, the 600 acres of Fooks’ run contained in the swamp remained in leasehold. Hughes had the impression that although Sand Hills was also at first worked as a dairy station, neither Moore nor Fooks had interest in the runs themselves. It took the swamp’s sub-division years later, for “men who knew how to work the land” to see the possibilities and potential benefits of drainage.24

Robert Heaton Rhodes bought much of Fooks’ run in 1869, seven years after Edward Reece bought up the swampiest ground in the Sand Hills. The two areas became known as Rhodes’ Swamp and Reece’s Swamp, which took until 1879 to be fully sold.25

Reece intended to farm the land he bought in 1862 from a John McLean, who had bought it from Wakefield’s New Zealand Company in 1860. It is not clear under what conditions the land sold, but Reece built a house on high ground overlooking Bottle Lake and expected to profit from fattening cattle on the rest. He became a well-known businessman and city councillor, but his farming venture failed. His cattle could not cope with the bog. He looked to other ways of making the land pay, and subdivided his road frontage into 10- and 20-acre lots.

The Drainage Board’s No. 1 Drain in 1939, along what had by then become Marshland Road. The water ran south into Horseshoe Lake. Hughes noted the lack of fencing in the area and that shelter belts, usually poplars, were trimmed for maximum sunlight.26 Could the young man with his back turned to the camera be Hughes’ way of leaving something of himself within his thesis?

Open drains along roads are still very much a part of the Marshland landscape, this one along Mairehau Road (formerly named Cemetery, then Reeves roads).

_______________

For years, the Avon Road Board had been hearing grievances about the lack of proper drainage of the land and roads north of the city.27 By 1874, Reese “discovered the whereabouts of a number of immigrants” at Holmes Bay on the Banks Peninsula, where several Polish families were “engaged in seasonal labour.”28 Most of these families arrived in Lyttelton via the friedeburg in August 1872, but families with children had struggled to find jobs.

The “balance of the immigrants” from the friedeburg had been “moving somewhat slowly,” reported the star on 18 September 1872.29 They seem to have been left to fend for themselves. The new zealand herald reported on 4 November 1875:

Some of the foreign immigrants by the Friedeburg have not met with much success in finding employment (says the Hawke's Bay Telegraph). Two men have travelled from Napier to Wairarapa and back again, and failed to get work. If the men were in earnest in their endeavour to get a living we can only attribute their want of success to their ignorance of the English language.30

The Pigeon Bay settlement at Banks Peninsula overlooks Holmes Bay (the two bays share an inlet) and the sea journey from Lyttelton harbour was then relatively short. One of the Pigeon Bay pioneers, Ebenezer Hay, introduced cocksfoot grass in 1852. Its seed harvest became almost as lucrative an industry for the area as wool, frozen meat, and wheat. Fourteen of the Polish men were employed to remove stumps from land at Pigeon Bay, but some collected cocksfoot grass seed, and received £30 for just two months’ work, so this may have been the “seasonal labour” to which Hughes was referring.31 These wages allowed the Poles to repay the colonial loans they took out for their passages.

Whatever the Poles understood of Reece’s offer, it led to several Polish families moving to Reece’s Swamp, and staying. Despite the challenges the land presented, and its austerity, leasing the 10- and 20-acre sections gave them control over their own lives. Some of the families made further informal subdivisions between themselves, and settled on adjoining five-acre lots.

The irony was not lost on them later that, after they had paid off the leases and drained the land, they had to pay substantially more to own outright the very land they had improved. Reports range between £10, £20, and £30 per acre for deals with both Reece and Rhodes.

This image has been touted as that of the friedeburg, but its provenance is not clear. The friedeburg was a three-masted 784-ton barque that sailed from Hamburg on 19 May 1872 and docked at Lyttelton with 241 statute adults on 30 Auggust 1872. (Children younger than 12 were classified as half an adult and babies as “souls.”)

Hughes mentions Schimanski (Szymański), Boloski, Rogal and Gearshearski (Gierszewski) as among the first Poles in Marshland; Gottermeyer and Lange among the first Germans; and Morton, Dunlop and Walter as among the first English. Other Poles had by then joined the friedeburg ones, often through family sponsorship.

Four Polish families that settled in Marshland, Borkowski, Roda, Rogal, and Suchomski, arrived in Wellington harbour aboard the cartvale early on a balmy Sunday, 11 October 1874. That day, another passenger, George Smith senior wrote in his diary:

Nothing more beautiful after a long sea journey than to wake up and find yourself anchored in one of the prettiest bays in the world. Surrounded by rugged hills with as pretty a little town as ever it was my good fortune to see.32

The 38-year-old’s fifth child was the first of 10 births during the 108-day voyage from London. Two of his other children had caught and survived the measles and whooping cough that was rife throughout the journey, and he declared that the sight of the yellow quarantine flag was “not as bad as you may think for there is a little island in the bay with a depot for the purposes of emigrants.”33

Carl Rogal (31) and his wife, Anna, née Domachowska (25), would not have been feeling as positive. Their 17-month-old son, Józef, died of diphtheritic croup on 17 July, the second of 19 infants and children younger than five to die aboard the cartvale. Five more died at Matiu/Somes Island’s quarantine barracks, the youngest, 12-day-old Clara Lee.

Smith wrote of a family “with measles… sent ashore” the day the ship sailed on 25 June 1874. The extent of their interaction with other passengers is unclear, but those still aboard were left to cope with the ship’s wretched living quarters and insalubrious rations.

The high number of deaths led to immigration officials personally inspecting the cartvale after the passengers disembarked, and before the “fittings” were removed. The inspectors did not have to look far before they realised their “worst anticipations… She was indeed in a filthy condition and the stench was abominable.” Bunks had been erected so tightly that effluent, slops, and pig muck had no way of escaping overboard; the sand that was supposed to help mop it up, ran out within three weeks at sea; and “scrapers” had broken on their first use.34

It became clear to the immigration officials in Wellington that the the ship’s captain and surgeon-superintendent had no experience in transporting and feeding large numbers of immigrants. Bread was sour and the food and fresh water soon ran out. George Smith refused the bread and was allocated flour in its place, so made a “large plum pudding,” which suggests that his family did not travel steerage. The damning reports on the cartvale and the douglas, which arrived in Wellington a few days later, led to led to future immigration ships being forced to provide better sleeping arrangements, better hygiene, more water, and more nutritional food. They received a direct order to feed children with preserved rather than salted meat, and to provide infants with milk, special food, and extra rations of water.35

Thomas and Marianna Borkowski embarked in London with five children. Albert, their youngest, was not quite 18 months’ when he died of measles on 9 October, two days before the ship arrived in Wellington harbour. Separate records show that Albert’s four-year-old brother, Stanisław, died of “pneumonia, congestion of the lungs” either on 12 or 20 October 1874.36 The older Borkowski daughters, Elizabeth (14), Franciszka (10), and Annie (8) survived.

The Roda (Rhode-Rohda-Rhock-Rhoda) family consisted of Albert (40) and Marianna, née Szmaglińska (33), their three children, Julianna (7), Johann (3) and the infant Józef, who died of impetigo and blood poisoning on 23 July 1874—the sixth cartvale death. The unpractised surgeon superintendent, Robert Robinson, wrote that “Jos. Rhock” had been “generally neglected by parents,” a ludicrous and insensitive remark considering that the “great deal of sickness” aboard the ship was later directly attributed to the fact that it was “teeming with filth” and that the “dietary scale” for the children especially was so woefully inadequate.37

On the ship’s manifesto, the family name was misspelt Rhock, and included Albert’s widowed mother, Magdalena, née Gierszewska, who was listed aged 45 rather than 55, his brother Johann (17), and his married sister Marianna Suchomska (27). According to her death certificate, Magdalena died in Papanui on 30 November 1876, aged 57, and was buried as Margaret Rode at an unnamed Christchurch cemetery.38

The cartvalemanifesto misspelt the family name Suchomski as Soukonesky. Marianna née Roda and her husband, Johann Suchomski (33), settled in Marshland with three-year-old Carl. Later versions of their name included Suhomski—which they adopted—Sokonieski, Schomski, Schowski and Swamski.

The friedeburg passenger list correctly spelt Albert Watembach’s surname, but used the germanised version of his and his wife’s first names, Albrecht and Catharina. Among Polish friends and family, they were known as Wojciech and Katarzyna, and in New Zealand, Katarzyna was also recorded as Katrina and Catherine. Her maiden name was Roda, and she was Marianna Suhomska’s and Albert Roda’s older sister. They came from Czersk in Prussian-partitioned north-western Poland.

There is no doubt that the Albert Watembachs encouraged the Roda and Suchomski families to join them in New Zealand.

Johann and Marianna Suchomski became known as John and Mary. Carl was 22 and known as Charles when he and his father were naturalised as farmers of Marshland on the same day in August 1893. The same year, Mary Suhomski’s name appeared in the Avon electorate on the world’s first-ever electoral roll for women. She died in 1908, aged 63, which spared her from being placed on New Zealand’s 1917 Enemy Aliens register, where John Suhomski senior appeared twice, as Schomaski and Schomski. Both entries noted that he was 76, that he had lived in New Zealand for 42 years, and that he resided in Waimari. He died in 1923, aged 81, and was buried with his wife at the Linwood cemetery.

According to the Christchurch diocese records, the Suhomskis had at least four more children, all baptised at the Church of the Blessed Sacrament in Barbadoes Street under different surnames: Anna Swamski in March 1876; Joseph Sohaomski in September 1879; Mary Schomski in August 1881; and John Suchomski in September 1885.

Anna’s records show that her father was John Swamski, her mother was Mary née Rody, that her godmother was Catherine Wattemburg. On her official birth record, she is Annie Suchemoki, and when she married John Falska in 1898, she was recorded as Annie Suchowski.

This is believed to be one of the Suhomski houses. The undated photograph comes from the collection of the late Martha Watemburg and shows a wooden addition to an early concrete and sod house. If you recognise the women, girl or house, please contact us through the get in touch option on our home page.

John and Mary Suhomski are among the many Poles interred at the Linwood cemetery in Christchurch. H-1

_______________

Mateusz (Maciej) Szymański arrived in New Zealand aboard the friedeburg as Mathias Schimansky, a single man aged 22. The ship’s manifesto showed that he had signed a £5 promissory note for his passage.

A Valentin Trymansky, aged 28, arrived in Port Chalmers on the palmersto in December 1872 but then seemed to disappear. The Schimanski variation of his name led the family’s descendants to speculate for years whether this was an older brother, Walentyn, but without recorded proof, have decided he was not.

Mathias settled in Marshland and wrote letters to encourage his family to join him, but when his brother Christoper arrived in 1883, the latter was furious that he had been duped about what to expect. Like several of the first Poles, Mathias glossed over the hardships of life in a new colony.

Mathias was born in Słupcina in 1851, in the Warmian-Masurian voivodeship of northern Poland. In New Zealand, his name was anglicised to Matthew Schimanski. As a single man, he quickly found a job, but his first was in Darfield, about 35 kilometres inland from Christchurch and therefore also 35 kilometres from the Polish families he had been with on the friedeburg—specifically the Burchards, whose eldest daughter was 17-year-old Julia.

Julianna (Julia) Burchard arrived with her parents Anna (née Kamieńska) and Adam Burchard and her three younger brothers, Johann (11), Theofil (4), and six-month-old Tomasz. It is not clear exactly where the family lived at first but, whenever he had the chance, Matthew Schimanski made the round trip to visit Julia. They married in August 1874, and had nine children before Julia died in childbirth, aged 40, a few months before their 20th wedding anniversary.

According to family story, Matthew arrived with his pockets full of onion seeds. If he did, it is not clear how he stored them until he was able to use them, but some of the Poles must have brought over vegetable seeds, including garlic, which Poles had learnt to use as a preservative during their frugal times in Prussian-partitioned Poland.

Schimanski family story tells that when Mathias arrived in Marshland, Canal Road did not reach Preston’s Road, there was no bridge over the Styx river, and the swamp already had a reputation: A Mr Blackburn, contracted to build the approach to the Styx, decided to use a team of six horses. The bog trapped, then swallowed them.

The youngest Schimanski daughters, Rose and Augusta, married Blackburn brothers Charles and John, so no doubt the Schimanski and Blackburn families had shared their stories of the early battles with the swamp, as there is a good chance that the Mr Blackburn who lost his team of horses was the brothers’ father.

Matthew and Julia Schimanski outside their Marshland home shortly before Julia died. Standing to the right are their eldest daughters, Johanna (Anna), Mary, and Martha. The trio on the left are Frank, Margaret (Magdalena), and John. Seated in front of their mother are Rose, Augusta, and Lil.

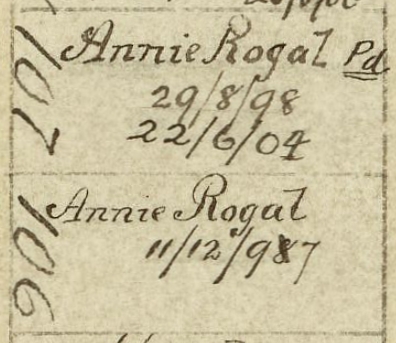

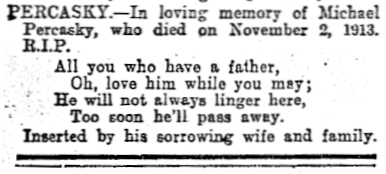

The widower Matthew Schimanski married widow Anna Rogal in 1899, a year after Charles Rogal died. The Rogals had had at least eight children in New Zealand: John in 1874, Frank in 1880, Mary in 1883, Leonard in 1886, Thomas in 1887, Theodore, who died aged four months in 1888, Helen in 1891, and Anthony in 1893.

The two families were already close, and Matthew Schimanski was helping the Rogals before and after Charles Rogal died. He enrolled Helen and Anthony Rogal as five-year-olds into Marshlands school in 1896 and 1898.

Anna Rogal Schimanski died aged 76 on 3 May 1925. She is buried at the Linwood cemetery next to her first husband and with two of their children, Mary, who died aged 21 in 1904, and Anthony, who died aged 29 in 1923.

The Christchurch City Council has digitised layout plans of the Linwood cemetery. This snip suggests that the widow Annie Rogal organised her own last resting place next to Charles eight months after he died, and that their daughter Mary was buried on 22 June 1904.

The Rogal headstone at Linwood cemetery in 2022, the lead lettering faded and torn, but still informative.H-2

Matthew died in 1933, and was buried with Julia a few metres from where the Rogals lie. The intact top piece of their headstone, like so many others at the Linwood cemetery, now lies on the ground. The section remaining does not mention their baby, who died the day before Julia.

Much of the leadwork has disappeared from Julia Schimanski’s much-earlier inscription. Pinholes and indentations show that she died aged 40, on 26 April 1894. Below her details were the words, “Thy will be done” and below that, “Mathew Schimanski, beloved husband of the above” who died aged 84, on 17 March 1933.H-3

_______________

Christopher (Christian) Szymański, two years older than Matthew, followed his brother to New Zealand in 1883. By then, the colonial government had long-stopped direct immigration from continental Europe, so Christopher and his family embarked the firth of forth in London.

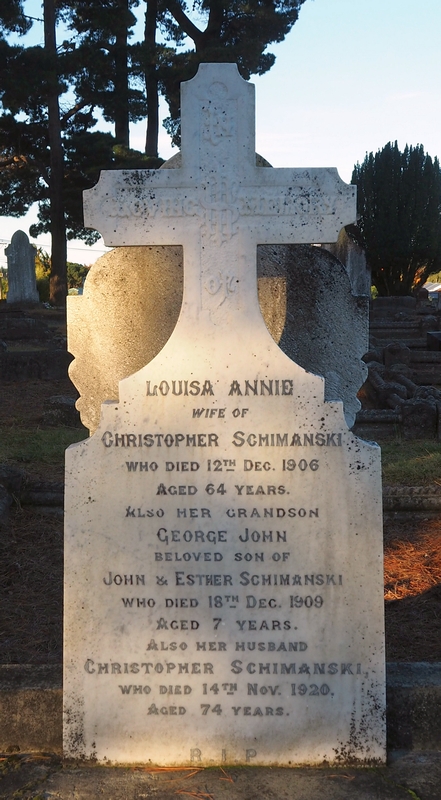

By then, the journey to Lyttelton was a mere 88 days. The Christchurch press noted on 6 February 1883 that the barque had arrived into port “in admirable order, creditable to its master and worthy chief officer.”39 Compared with the 418 hapless souls on the cartvale nine years earlier, the firth of forth carried 19 crew and only 31 passengers, including Christopher’s wife, Louisa, née Nikiel (40), their children Julia (9), Augusta (5), and Mary (3), and Louisa’s sons from her marriage to the late Julian Szaluga, Martin (16) and Michael (13).

The captain knew “Mrs Schimanski” well enough to note in his logbook that she had “been confirmed of a boy” (John) at 5.30pm on 17 January 1883, a Wednesday of wind, rain squalls, and seas that tossed the ship’s human cargo around “like a lot of pieces of soap.”40 The press mentioned the birth in its 6 February story.

However annoyed Christopher Schimanski had been with his brother for glossing over his living conditions, he accepted the situation and settled into the life of a New Zealand market gardener. He and his family lived next door to Marshland School on Marshland Road, and Matthew lived opposite with his own growing family On 30 August 1887, the Schimanski brothers were naturalised together—as farmers—at Bottle Lake. A 1915 map reveals that their extended families lived near one another on the four blocks crossed by Marshland and Preston’s roads, and near other Polish families such as Boloski, Gorinski, Kiesanowski, Rogal, and Rogatski, through which they became linked by marriages. Both brothers named a son John and a daughter Augusta, which would have complicated matters for outsiders.

Christopher Schimanski, left, outside his house on Marshland Road with his wife, Louisa, in the apron on the veranda, and some of their family. Next to Christopher are Mary and John. Almost hidden behind the shrubs near his mother is Albert, their only child born in New Zealand. With her mother on the veranda is Julia, holding her sister Augusta’s baby. Augusta is on the far right, and her husband, Jack Boloski, is the man in the middle.

The last rays of a May afternoon catch Christopher and Louisa Schimanski's headstone in the Linwood cemetery, Christchurch. Louisa died in 1906, and Christopher in 1920. They share their grave with their grandson George John, who died in 1909 aged seven.H-4

_______________

Any of the men who were aged between 20 and 39 when they arrived in New Zealand from Prussian-partitioned Poland were either supposed to be serving in the Prussian army, or be available as reservists.

The conscription system responsible for the Prussian victory in the 1871–1872 Prussian-Franco war allowed few men to escape its strict rules—rules borne from a decades-long Prussian strategy of building an army of well-trained and war-ready reservists. At 20, men spent three years in military service, then another two in the reserve force, and a further 14 in a stand-by force.

Brothers Jan and Michał Gierszewski were technically still indentured as reservists when they left Prussian-partitioned Poland, separately. They had the added motivation of protecting their sons: in 1872, both had sons aged seven, and Michał also had five-year-old Leo. Polish birth records spelt their surnames Górczewski and Gerszewski.

The overwhelming triumph against the French encouraged German chancellor Otto von Bismarck to pursue his quest to build a great German Empire out of its many states, and to create a population of “good Lutheran Germans.” Life had been harsh for Poles in Prussian-partitioned Poland before that war, but became wretched as Bismarck outlawed their rights, their language, their Catholicism, and stripped them of their livelihoods to the extent that they often existed on the edge of starvation.

The friedeburg manifesto, spelt Jan Gierzewski’s name Johann Georgewski. It had his correct age, 34. With him were his wife, Rosalia née Pyszka (36), their son Simon (7) and their daughter Anna (18 months). Jan became known in New Zealand as John, and was soon encouraging Michał, five years his junior, to join him.

The Michał Gierszewskis left their home in Czersk in 1873 with Katarzyna’s brother, Walentyn Cieszanowski (34), and his wife, Anna, née Ebertowska (24). Both men were tailors, trained by the sibling’s father, also Walentyn. The Prussians spelt Michał as Michael, Walentyn as Valentin, and Katarzyna as Catharina.

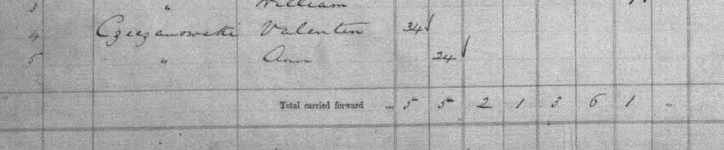

According to the humboldt passenger list, the families left “Hamburgh” on 30 June 1873 and arrived in Maryborough, Queensland, on 29 October 1873. The ship’s manifesto shows Cieszanowski as Czrezanowski, and Gierszewski as Gerschefske. Michał and his family received “free” passage; Walentyn and Anna “assisted.” It is not clear why they travelled to Australia, or how they arrived in New Zealand.

The Gierszewski and Cieszanowski entries in the humboldt passenger list.

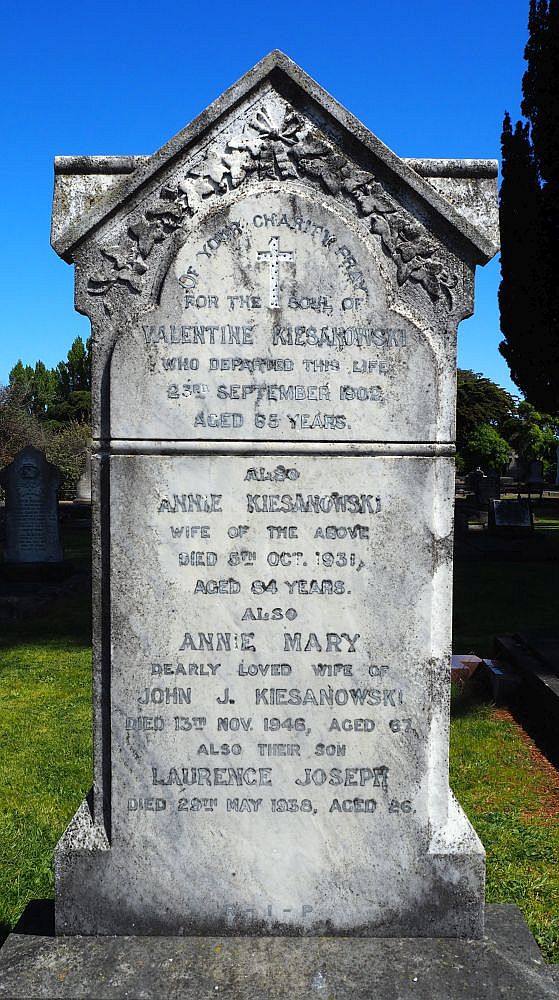

Instead of being saved, the little boys Jan and Leonhard died at sea. Gierszewski descendant, Margaret Copland: “The boat was crowded and dirty. As the ship neared the tropics one family of children became sick with a high fever… The fever passed from child to child. Every few days a child would recover, or a child would die…”41

Officially, one 25-year-old woman, 15 children aged between two and nine, and six babies died. The records show those 22 as 8½ “statute adults.”42 The shared death record of a Valentin (34) and an Ann (24) Czsezanowaki held by the Australian archives remains a mystery. Both apparently ‘died’ aboard the humboldt. The lack of all but their misspelt names and ages suggests they may have wanted to disappear.

By 1876, Michał Gierszewski and Walentyn Cieszanowski had brought their families to Marshland, but Walentyn (as Valentine Kiesanowski) quickly decided to follow his trade in the then more prosperous Thames.

Wilfred Walter remembered that John “Gearschowski” built a “two-roomed dwelling with thatched roof. There was nothing stylish about it. He sank an artesian close to the house and I believe it is still to be found there. Some years later he left for America.” Walter recalled that before the Pole left, he had owned a block on the corner of Hill’s and Lange’s roads, “just past Mr Lange’s” and had erected “a substantial house.”43

Michael Gearschawski lived farther along on the opposite side of the road. He “built a modest house and after demolishing it, he erected a two-storey house to meet the demands of his growing family. This house is still to be seen on the property… he farmed a fairly large block of land.”44

According to baptism records, Michael and Catherine Gierszewski had at least four more children: Mary, who was baptised at the Catholic Catholic Church of the Blessed Sacrament in Barbadoes Street in 1876; Frances, who was baptised in 1878; Annie, who was baptised in 1880 and whose godmother was Catherine Watemburg; and Joanna, who was baptised in 1881 and whose godparents were Matthew and Julianna Schimanski.

John Gierchwski advertised his land in the lyttelton times on 10 April 1884:

LEASE FOR SALE. —20 Acres of rich Land at Rhodes’ Swamp; House, and other buildings, 3 miles from Christchurch. Splendid land for Root Crop or Grass, with 3 acres carrots. Present owner can give good reasons for selling. Stock and Plant can be taken at valuation.45

John and his family seemed to have moved for a short time to Carterton, then by 1886 to the United States. Their son Simon seems to have disappeared. Some stories say that he died aboard the friedeburg, but that ship recorded only one death, an 11-month-old boy.

Michael’s naturalisation stated that he lived in Bottle Lake. In 1904 he advertised his 10-acre property on Preston’s Road for rent with “immediate possession.”46 He appeared on the 1917 New Zealand Enemy Alien record as M Gearschawski, aged 74 and born in Germany [sic]. He died at Hill’s Road, Marshland, aged 86.

Catherine Gearschawski appeared on the first electoral roll for women, in 1893. Her address was Canal Reserve and her occupation “domestic duties.” Like her husband, the New Zealand 1917 Enemy Alien record says she was born in Germany. She died in 1925, also aged 86.

Catharina Cierzanowska and Michael Gierszewski married in the Czersk parish of Prussian-partitioned northwest Poland on 9 May 1864. She was 25 and he was 23. They both lived to 86. Their headstone in the Linwood cemetery fell in the 2011 earthquakes.H-5

_______________

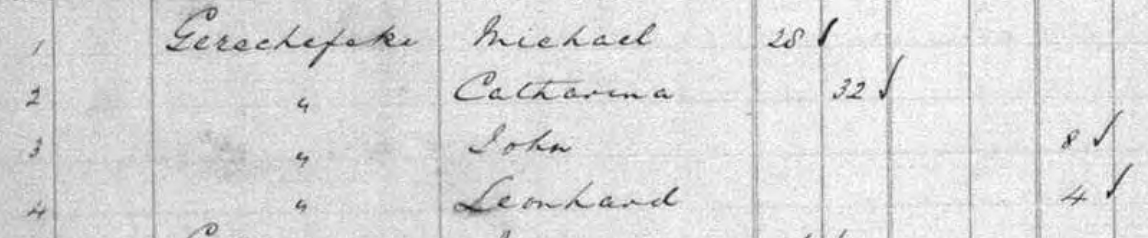

From October 1876 to December 1878, Valentine Kiesanowski placed more than 300 large advertisements in the thames advertiser and the thames star:47

They were replaced by one-line lower-case advertisements under “Tailors,” then tailed off and completely disappeared for a few years before they returned in block form in December 1884: “V KIESANOWSKI, TAILOR… ALL KINDS OF WORK executed on the shortest notice, on the most reasonable terms.” His last public message on 31 August 1886 reminded Thames residents that his prices were as “moderate as ever” and that he guaranteed “the best of Workmanship.”48

Valentine did turn to farming in Marshland, according to his letter of naturalisation dated 24 August 1893. His brother-in-law, Michael “Gearschawiski” received his the same day and a week later, his son John, born in Australia, received his, with father and son John and Charles Suhomski.

Valentine and Annie Kiesanowski had at least four more children in New Zealand: Cissy in 1879; Joseph Francis in 1881; Annie in 1884; and Edward in 1888.

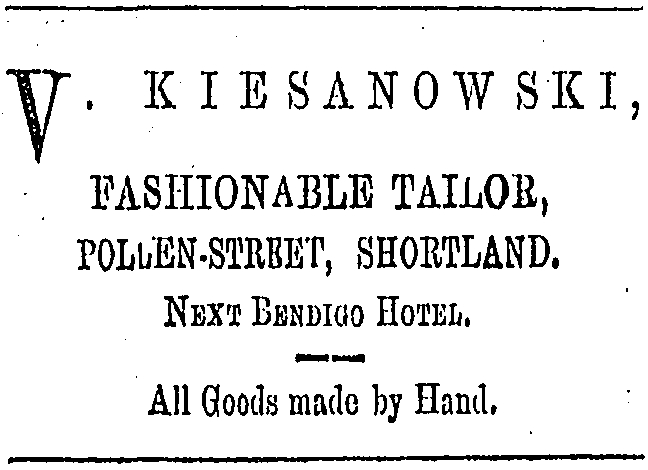

The Kiesanowski headstone is among the few unscathed by the 2011 Christchurch earthquake. Valentine Kiesanowski died on 23 September 1902, aged 65. Annie survived him by nearly 30 years. They share their grave with their daughter-in-law, John’s wife, Annie Mary (née Rogatski), and their grandson, Laurence Joseph, who died aged 26.H-6

_______________

In February 1884, an RH Rhodes advertised for surveyors “for Land Transfer Act purposes” on 1,000 acres of his Marshland estate.49 Robert Heaton Rhodes died three and a half months’ later, aged 69. His eldest son, also Robert Heaton, but who became Sir Heaton Rhodes, was then 23. The senior Rhodes’ full-column obituary in the lyttelton times mentioned that:

At Papanui he devoted himself to increasing the value of what was then known as Rhodes’ Swamp, but is now the Marshland estate on the Canal Reserve, near Horseshoe Lake. In draining this land, he expended, it is believed, something like ₤5,000, besides giving his time, and frequently personal labour, to the work.50

The obituary said that the inhabitants of Christchurch owed the Cathedral tower and eight of its 10 bells to Rhodes’ “munificence.” The other two bells were donated by a Mr Miles of the conveyancing firm Miles & Co, which handled Rhodes’ land affairs. The Miles name continued to appear in transactions involving the Rhodes estate and other Marshland residents.

Three weeks after Rhodes’ death, Miles & Co ran a series of advertisements in both the press and the lyttelton times that called for five-year leases on two of the Rhodes blocks. Two of the crops “may be taken off,” they said, ready for the land to be “laid down with English grass to the satisfaction of the landlords.”51

Wakefield’s and Godley’s “men of capital” had indeed been able to acquire the original land cheaply: a farthing is a quarter of a penny, so 5,000 acres—one of the smallest original Waste Board blocks—would have cost little more than £5 to secure in 1860, the equivalent of one sea passage in 1872. Speculators such as Edward Reece and Robert Rhodes may not have followed Godley’s “men of capital” rule-book in that they did not keep their massive estates intact, but their subdivisions, and land sales to men without capital increased their wealth exponentially.

Judging by the long and hard hours that the first settlers put into their 5-, 10-, and 20-acre leased sections, one wonders what Rhodes’ obituary writer meant by the “frequently personal labour” that his subject put into land multiple times the size. By draining the leased land, the labourer-settlers certainly improved its value.

By the time Reece met the Poles in Banks Peninsula, he had divided the swampiest part of his land farthest from his homestead into 10- and 20-acre blocks, and offered them as 10-year leases at 30 shillings a year. Hughes remarked in his thesis that “in many cases the Poles bought their sections before the time was up.” Rather than raise a loan during a time when interest rates were high, they paid off their land year by year, at ₤30 an acre—10 times the cost 10 years earlier. Hughes called it “a very high price” considering the state of the land.52

It is not clear what exactly those interest rates were. Canterbury newspapers in 1884 show advertisements offering a rate of six percent for lenders, but several firms offering “lowest” rates for borrowers did not state the terms.

Any of the Marshland settlers who had taken up the leases would soon have realised that the longer they worked on draining the land, the more viable and expensive it became, so no wonder they tried to speed up the process.

_______________

Wilfred John Walter’s father, Charles Henry Walter arrived in Canterbury via the zambia in 1863 and farmed 22 acres alongside a track adjacent to the Rhodes Main Drain, and then on Hill’s and McSaveney’s roads.

On the first page of his memoirs, Wilfred Walter described the family’s first thatched-roofed, three-roomed sod house, built by John McSaveney. The main room was “roughly boarded,” but the others had bare, clay floors. Candles “sufficed as lighting and afterwards kerosene lamps were used.”

The house may have been basic, but it was solidly built, as the family discovered in 1888 when a “terrific earthquake almost tossed us out… we thought the house was collapsing. The top of the Christchurch Cathedral Spire fell to the footpath below…”53

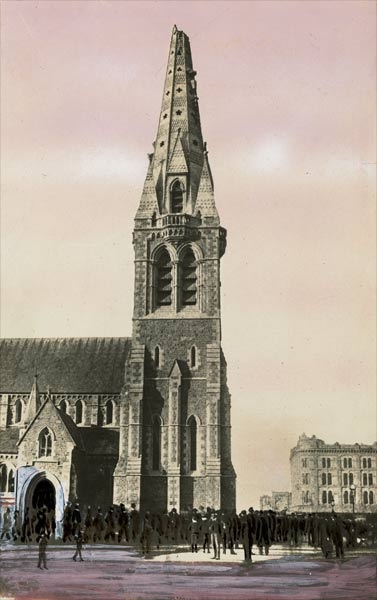

This image of of the Christchurch cathedral, missing its top 7.8 metres of stone spire after the 1 September 1888 earthquake, comes from te ara the encyclopedia of new zealand. According to the accompanying caption, the spire was repaired, but 1.5 metres fell again in an 1901 earthquake, and was later remodelled in hardwood sheathed in copper.54

The drama of the earthquakes faded as the settlers continued to deal with living on the swamp.

Walter: “The half-chain road [in front of the Walter property], now named Walters Road, was well-known in the early days… It was not really a public road then, being meant as a right-of-way for the residents… seven gateways had to be opened and closed before getting to the end of it. This roadway was at best a rough and tumble journey, and in the winter months it was nothing better than a quagmire. Loads of gorse were strewn over it to make it safe and negotiable, but even then, it often had to be abandoned, and resort made to travelling through the adjoining paddocks.”55

In 1882, the less than a kilometre length of McSaveney’s Road from Hill’s Road to Marshland Road was “a beaten track—sledges being used to bring produce by the settlers living along the road to Hill’s Road, for loading on to carts for the market.”56

“A rightaway, a grass track, extended from McSaveney’s Road along the west side to Mr Albert Rhoda’s place, this being a convenience to all the settlers getting in and out of their respective properties. Being soft soil, it easily cut up with traffic, and many were the tough and boggy trips taking produce out to McSaveney’s Road. In the winter time horses would bog down pulling loads up to their bellies… at this time of the year was like a river of mud.”57

A Marshland team harrowing after autumn ploughing. Most farmers used two horses.58 John Blackburn, recalled his father-in-law Matthew Schimanski using bullocks rather than horses to plough.59

The poor state of the roads in Marshland became a long-standing grievance among its residents. In May 1871, “Swampy” complained to the editor of the press about Marshland’s higher council rates being used for the upkeep of roads in south Christchurch, while theirs farther north were being ignored. He had found out that, after the upgrade of their own roads, a “wealthy and educated” group in south Christchurch had petitioned the council to allow them to be separated from the Marshland area’s roads. “Swampy” said this would:

… leave out all the roads that are costly to keep, those not yet made, the river, the frightfully expensive main drains—about eight miles of the North road—the Sandhills, the Swamps, where the flax still grows on the roads…60

Environment Canterbury: “The northern end of Hill’s Rd follows the edge of the old swamp… the only safe route through the area at the time. The construction of roads required extensive and continuous work due to sand and metal fill being swallowed by the bog. By the early 1900s the roads in Marshland were stable enough to become popular travelling routes.”61

To take their produce to the Papanui Railway Station, residents from eastern Marshland used Winter’s Road, which then extended from Hill’s Road to Canal Reserve. For many years, Winter’s Road was “just a grass track” but increased demand led to authorities pouring metal from the Styx River shingle pit onto the east end of the road. Even so, “the road was full of deep ruts, and it was heavy and slow pulling for even a good horse to pull a dray with a ton on it.”62

A “number of creeks” crossed the track on the Walter farm and Wilfred Walter recalled his family’s surprise that the settlers using the bridges “not safe for traffic” did so continually and without incident. Any travel within the swamp area was precarious. The Maffey holding near to the Walter farm, for example, was “a wilderness… full of deep springs, one being considered so deep it was said to have no bottom to it. It was called ‘Balley’s Hole.’”63

One cattle drive, by a man called Holmes, made a lasting impression on a young Walter:

“They arrived on a Saturday and on Sunday about twenty head were in the drains, several being drowned. Sheep were also tried for grazing on this place but they too fared no better than the cattle, quite a number being drowned in the drains… The job then was to pull the carcasses out and skin them.”64

A Mr R Gibb reminded Walter during his interview in October 1937 about Old Joe, “a remarkable bullock” owned by the Hawken family, “a champion puller, especially pulling cattle out of the drains, a very common occurrence in those days. He became cunning in objecting… but this was overcome by blindfolding him and then attaching him to the bullock in the drain.”65

The Walter farm was later divided and taken over by a Thomas Wilson, who arrived as an infant off one of the first four ships in 1850, the charlotte jane,66 and Frank Rogatski (Rogacki) senior, who arrived in Port Chalmers off the palmerston in 1872, aged 26, with his wife, Paulina, aged 21.

Just a few kilometres north of Marshland, the 13-hectacre freshwater wetland, Ōtukaikino, is being restored. Visitors are reminded not to venture off the tracks and boardwalk.

_______________

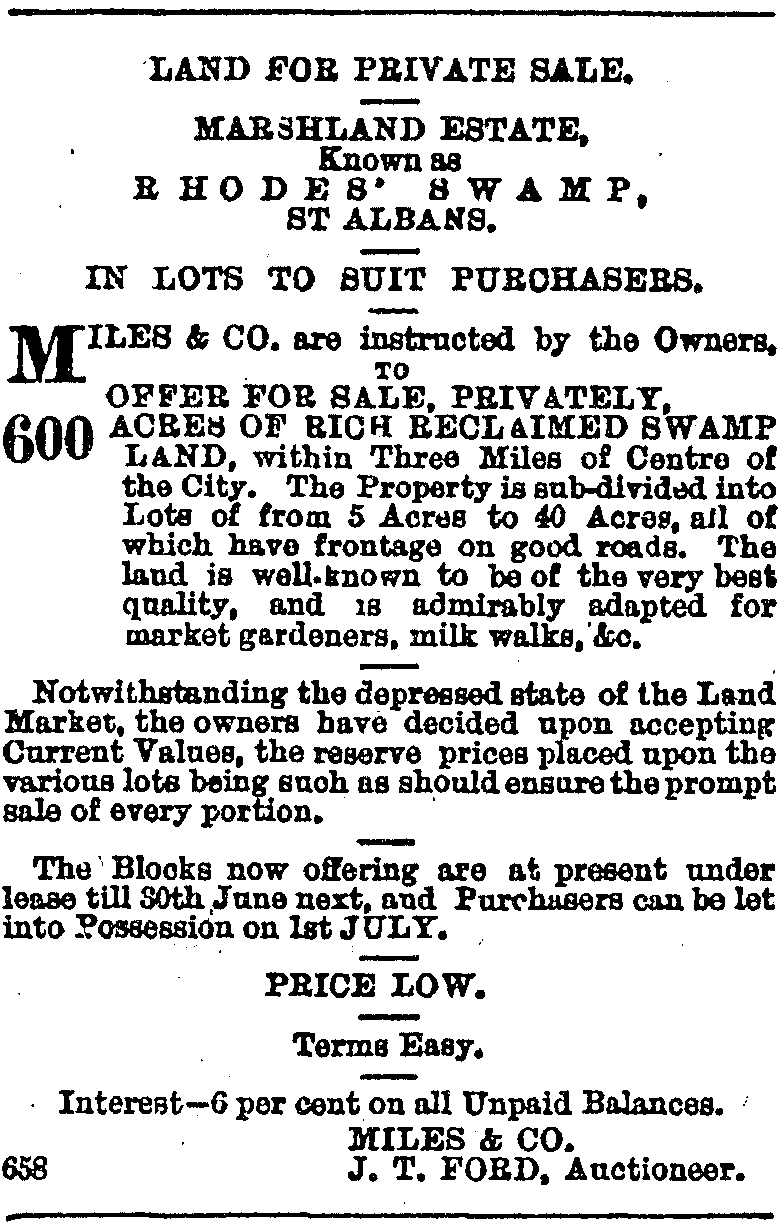

By May 1886, the executors of the Rhodes estate started to sell its leased, reclaimed land. Advertisements tended to appear in tandem in the press and the lyttelton times, this one on 8 May.67

The advertisement does not name the “good roads,” nor the price of the lots, but acknowledged the “depressed state of the Land Market” and confirmed the six percent interest rate.

A week later, in its auctioneer’s report, Miles & Co. disclosed “eager enquiries” that bought nearly 78 acres at an average of £87 7s 64d per acre.68

Not all property buyers considered the land as valuable as that. The following week, Miles & Co squeezed in a sentence at the end of their report: “Privately during the week we have sold further portions of the Marshland Estate, amounting to eighty-nine acres, at prices varying £35 to £40 per acre.”69

On 27 August 1887, under the heading “Commercial,” the lyttelton times told of another private sale: “Part lot 19, part of the Marshland Estate, 18 acres at £31 an acre.”

On 22 October 1887, the press reported that it was “a pleasing feature in the face of the general cry of depression and scarcity of money, to be able to record a satisfactory sale of land, and we have much pleasure in announcing the sale of two small farms, part of the Marshland Estate, one at £38, and the other at £37 per acre, a very considerable portion of the purchase money being paid in cash.”

The road along the north-west boundary of Marshland, now Hawkins Road, is named after Henry Hawken. According to the Christchurch City Libraries, he arrived with his wife and four children in Lyttelton via the accrington in 1863, leased the first block on Rhodes Swamp—on the corner of now Hawkins and Prestons roads—and built one of the first two sod huts in the district.70 Some sections of the road are today divided into quarter-acres; elsewhere huge paddocks predominate.

From December 1887, the Rhodes estate began a concerted newspaper advertising campaign for 240 acres “lately occupied by Messrs A and EJ Hawken,” which it said was the “finest portion of the Marshland estate.” In the same column, the estate offered weekly grazing for cattle.71

That December, Hawken’s 240 acres were offered for sale at least 16 times in the two local newspapers. The advertisements tailed off by the end of February but by June, the estate was again offering 200 acres of the Hawken land, calling it “a further portion.” The same wording continued to appear until late December 1888.72

Wilfred Walter believed the land represented most of the Rhodes estate north of McSaveney’s Road, some immediately south, and that nearly all the settlers bought the places they held under lease at prices that ranged from ₤30 to ₤37 10s an acre:

“This changeover from leasehold tenure to freehold led to a great progressive movement in the district. Old shacks gave way to better habitations, the land was given better attention, and treatment and production of crops considerably increased…”73

Hughes captured this image of the only remaining specimen of an old sod house on Reeves Road, made either of sod or cob and wood and bearing “silent witness to the endeavours of the early settlers to utilise those materials already existing in the district.” Made entirely of sun-dried sod plastered with clay, it stood high on a sandhill, had two rooms—each with a small window—a front door, and a back door. Hughes found a “diminutive rusty stove” in the chimney stack at the eastern end of house, a shattered lamp on its “rude wooden mantel piece,” and “rough floral wallpaper peel[ing] off walls shaking in the wind.”74 Reeves Road had previously been named Cemetery Road and is now Mairehau Road.75

_______________

Hughes described Marshland Poles as “energetic, enduring, patient… Marshland owes its status as a prosperous and thriving community… to the nature of its Polish settlers, their triumph in the face of adversity, and their victory over natural odds perhaps greater than those of any other district in New Zealand.”76

What drove Hughes to come to this conclusion? He admits that “time at our disposal [for interviews and research] was extremely limited, and our knowledge of the district at the outset nil.”77

Hughes focussed on 15 families “whose names show them to be of Polish extraction” and seven German ones—but named few. He wondered what brought them to New Zealand and spoke to an unnamed “old settler.” Hughes wrote about Matthew Schimanski, who “slipped out of his village one night and made his way to London,”78 but could not have spoken to him, as he died in 1933 and would have told the student-teacher that he had boarded the friedeburg in Hamburg. One could surmise that Hughes mixed up the Schimanski brothers, because it was Christopher Schimanski’s family that arrived from London in 1883, and they would have slipped away from their Prussian-partitioned Polish village without fuss.

Hughes: “Strange irony of fate that the ‘blood and iron’ of Bismarck should lead to the establishment of a progressive, hard-working community in New Zealand.”79

Hughes analysed the adult Marshland community through the “most recent” Kaiapoi electoral roll (1938). He found approximately 500 people in Marshland, 275 eligible to vote. The 142 men were made up of 87 farmers, 36 farm labourers, and 19 “trades and professionals.” The 133 women voters had two categories, married women, and widows (114) and spinsters (19).80

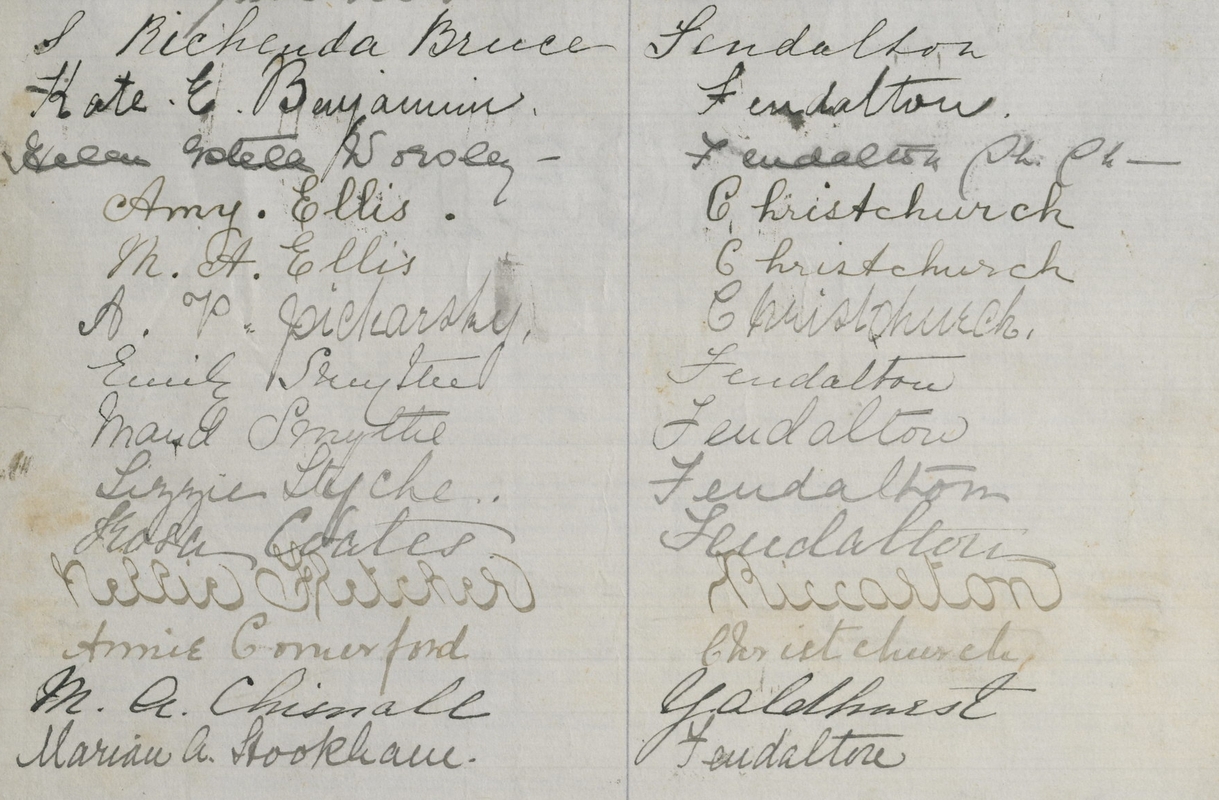

Within the Kaiapoi electorate in 1938, 76 people shared 21 Polish names. Polish Marshland families included Boloski, Borcoskie, Gdanitz, Gearschawski, Rogal, Schimanski, and Sharlick. An Anthony Gorinski, who attended Yaldhurst School in 1917, lived with his family on Preston’s Road. The Dunicks lived in Ohoka, the Grofskis and Percaskys in Papanui and the Rogatskis in Hornby.81

Hughes felt that Marshland residents held a “distinct apathy” towards its local government, but their apparent lack of community consciousness did not surprise him, as it reflected New Zealand at the time.

He blamed the proliferation of counties and local bodies: Originally Canterbury had five counties, but a pound-for-pound government subsidy of up to ₤25,000 per county resulted in districts dividing into smaller and smaller entities—129 counties and 700 local bodies soon overwhelmed New Zealand with “an unnecessary superstructure… a drag on the country’s political and social progress and evolution” that permitted “large control by single families.”82

Hughes may have thought he had found in the Marshland Poles a unique community to dissect, because he clearly did not know about other Polish communities of comparable size in Otago or Taranaki. He noted: “There may have been further isolated occurrences of Polish immigration up to 1900, but if such was the case there is no record of it in the NZ Year Book for those years.”

To supplement the “short time” he had to “move among the people,” he asked 55 pupils of the Marshland school to fill out a questionnaire.83

Marshland school, on the corner of Preston’s and Marshland roads, in 1939.

The school opened in June 1888 with 34 children who had previously travelled to classes in Papanui and whose families had petitioned the Education Board for a local school. The Rhodes trustees donated the land. The board called for tenders for the school’s buildings and a master’s house and by May 1888, was advertising for a “Rhodes Swamp—Master. New School. Salary according to scale, probably ₤150.”84

According to the school register on 25 June 1888, Mary Rogal, living in Styx, was the first Polish child to be admitted. A day later, Christopher Schimanski, who lived a few hundred metres from the school, enrolled his children Mary and John. On 9 July he did the same for his nieces Margaret, Martha, and Minnie Schimanski.

It is not clear who the pupil Annie Dechjeski was, but her father, recorded as “N Dechjeski” of Canal Road, enrolled her on 23 July. Albert Watemburg enrolled his children John and Annie on 25 and 26 September. On 12 November 1888, John Suchomski enrolled his daughter Mary, the last Polish child at the school that first year.85

A year later, the roll had grown to 110 pupils with two teachers. David Dunlop told Wilfred Walter about the success of the night language classes that the headmaster, a Mr A Malcolm, conducted during the winters of 1889 and 1890, and of the dinner service that the attendees gave him as a mark of their appreciation.

David Dunlop arrived with his parents in Lyttelton on the brothers pride in 1863. The family settled in Marshland after David Dunlop senior, described on the passsenger list as a “ploughman,” bought 94 acres on Canal Reserve in “about” 1876. David junior’s mother, Jeanie, planted most of the gorse fences on their property and travellers along the grass road in front had to open and close a gate to get through. David junior recalled the sand formations, already as high as their land, and “growing even higher.”86

The school soon became the core of the community, which in 1939 included a hall, a general store, a service station, and Anglican, Methodist, and Roman Catholic churches.

The Marshland store in 1939, opposite the school. The service station on the left of the photograph is farther along Marshland Road.87

Mr Reece offered his Bottle Lake grounds to the school for some of its first annual picnics, always well-attended by pupils and adults. In 1893, “about 500” attendees used “every vehicle in the district… for their conveyance.” Teacher Miss F Dick was praised for organising the children in concerts and was “sorely missed” when she moved to a headmistress position elsewhere. Mr Malcolm and his staff were credited for the nearly 100 percent attendance and the 74 percent average class mark, although only half the children “passed” in any year.88

In 1895, after schooling stopped for 10 days to allow pupils to help with the local potato harvest, the school board adopted the practice every October for “weeding” holidays.89

Hughes’ school survey revealed that in 1939:

—The average household consisted of six people.

—53 of the houses had electricity but only two had exchanged exchanged their wood and coal ranges for an electric

stove.

—49 had bathrooms but only 23 had both hot and cold running water.

—There was no sewerage system, but some modern homes had septic tanks. Outhouses, “in common with many farms in

NZ [were] temporary structures constructed of any waste material… rusty sheet metal and rough timber.”

—Despite houses having an “ample number of rooms” the kitchen tended to “serve the purpose of a

living room [and] regarded as the centre of family life.”

—10 homes had telephones.

—52 families took one of the daily newspapers, the press, or the

sun, and five took both.

—18 families had pianos, four had accordions, six had ukuleles, three had organs, one had a guitar, and one had a

banjo. Hughes did not say whether some families had multiple instruments.

—11 of the music teacher’s 14 pupils came from the Rhodes Swamp School, the children taught “for social

purposes.” Prior to a music teacher, the accordion was the chief musical instrument.90

In his thesis, Hughes included the views of an unnamed wife of a “professional man.” She described the Marshland people as “the kitchen type,” a judgement that may have clouded Hughes’ own assessment of the homes he visited.91 He pronounced the more prosperous dwellings as “bright and cheerful,” whereas most of the Polish homes had “monotonous floral wallpaper. This dreary aspect relieved by an occasional picture.” He wrote of “little artistic appreciation” in the homes, where many mantelpieces had cards bearing religious inscriptions, which Hughes called “symbolic of good intentions” and an “indication of the family’s good Faith… rarely taken notice of.”92

The Marshland Poles would have been mortified by the young man’s conclusions, especially those regarding their faith. Polish families prayed together daily, went to Mass on Sundays, and celebrated feast days as a community. Like other Poles who settled in New Zealand in the 1870s and 1880s, they were staunchly Catholic and had learnt religious resilience: One of their reasons for leaving Prussian-partitioned Poland in the 1870s and 1880s was exactly Bismarck’s ban on their religious freedom. Polish priests in Prussian- and Russian-partitioned Poland—if not deported, murdered, or banished to Siberia—practised covertly, so the Poles were used to praying without fanfare.

In New Zealand, Catholic Bishop Redwood, once he realised in 1876 that increased Catholic immigration included a growing number of Poles—more than 1,30093—invited a French colleague, Father Anthony Halbwachs, to join two other priests and “four Christian brothers”94 in the new colony.

They arrived on 15 May 1876 on the ss easby. Father Halbwachs and the Poles shared a common understanding of German but the priest also “gave eloquent sermons” in English. Bishop Redwood sent him to the Wairarapa in the south-central North Island, where within three months he had started advertising for builders for a presbytery in Carterton. On 5 May 1878, as Bishop Redwood consecrated the new Catholic church “of architectural beauty” in Carterton, Father Halbwachs was already planning to build churches in Masterton, Greytown and Featherston95 and later, Tinui.96

A newly arrived Father Grunholz, who “solemnised High Mass” at the consecration of Halbwachs’ Masterton church in June 1879, had been sent to New Zealand on a mission with “special reference to the many Polish families now scattered through the colony.”97

The Church transferred Father Halbwachs to Reefton in 1884 after he became unable to repay personal loans he had secured for the building projects. Before the introduction of Parish Councils and Finance Committees, money for building churches had to be registered as personal loans to the parish priests. Father Halbwachs took on such personal loans but was unable to repay ₤1,000.98

By September that year, Father Halbwachs had moved to Christchurch, where he spent six years before another transfer, to his last assignment in New Zealand, the Shand’s Track Catholic Mission, near Lincoln.99

Rosalia Gierszewska walked from Pigeon Bay on the Banks Peninsula to the Station of the Assumption on Shand’s Track when she found out there was a priest available to baptise her child, Carl, registered in Akaroa in 1873. Today the shortest route to that first Lincoln church is a 63-kilometre trip over the Banks Peninsula.

Margaret Copland: “It was part of the Christchurch parish, which covered the whole of Canterbury. There were two, possibly three, priests, generally French Marist, who did a lot of travelling by boat and on foot.

“When the Poles arrived in Marshland, the only Catholic church in Christchurch was the Church of the Blessed Sacrament. The Polish people went to Mass there whenever they could. There were regular Masses in Papanui, and the Sisters of the Good Shepherd had a house in Manchester Street, which was later taken over by the North Christchurch Parish of St Mary’s.”

The Church of the Blessed Sacrament in Barbadoes Street was opened in 1865, enlarged in 1876 and 1877 and replaced by the Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament, which was badly damaged in the 2010 and 2011 Christchurch earthquakes, and which is now being demolished.100

Construction for the new Catholic Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament began in 1901, and took four years.101

Before the Marshland school opened, Polish children, including Margaret Copland’s grandfather, John Thomas Borcoskie, attended the one attached to the Catholic chapel in Papanui. His parents, Thomas and Marianna née Kowalewska Borkowski, arrived on the ss cartvale in 1874 with his three sisters, and settled in Marshland, where he was born in 1875 and his younger brother, Ignatius Joseph (Joe), born in 1877, who was the last of Thomas and Marianna’s children.

Sundays at St Mary’s Church became the main social event of the week. Drays full of children raced one another to get there, and after Mass, the Polish congregation lingered. A Sr Anglela told Margaret Copland that their conversations often lasted an hour or more:

“Their horses and carts were all lined up together, the men would be in one group, the women in another. Everyone would be talking in Polish.

“The Marshland Catholic Church was built in 1927 and closed in 1974. It never had its own priest and was managed from St Mary’s. The priests tended to be Irish, and one called all the women by the same fake name, something like Mrs Wiskenski.”

The Borkowski name changed to Borkoski, then Borcoski and Borcoskie. Thomas was naturalised at Bottle Lake in 1887 as Borkoski, his occupation, farmer. He appears on the 1896 Avon electoral roll as Thomas Bokosky. Marianna Borkoski died of influenza in 1911, aged 77, and is buried at the Linwood cemetery as Mary Ann Borkoski.

Although Thomas Borkoski died only five years later, the two are buried a few metres apart. Marianna shares her grave with her son-in-law George Fuller, who died of broncho pneumonia two years after her, and and George’s wife, her third daughter Annie Fuller, who died aged 80 in 1948.

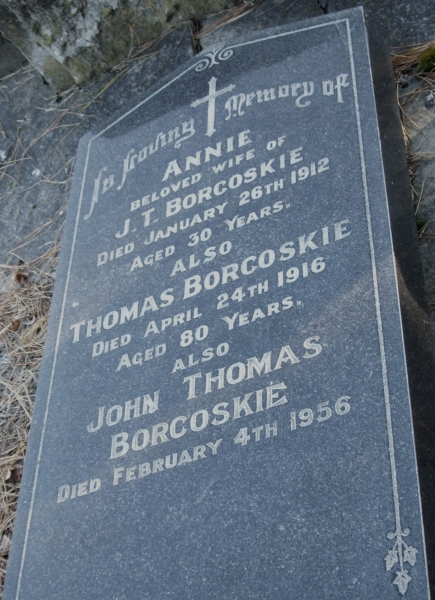

Thomas died aged 81, and is buried with his daughter-in-law, Annie née Gierszawski Borcoskie, who died as a mother of five aged 30 in 1912, and Annie’s husband, his son, John Thomas, who died aged 81 in 1956.102

Thomas and Marianna’s eldest daughter, Elizabeth Borkoski, married William Forsyth in 1886. Their marriage certificate shows that she was 25 and worked as a servant and that he was 26 and a baker. They had 10 children. Elizabeth Forsyth died in 1920, and is buried at the Bromley cemetery with her husband, who died in 1950.

Their second daughter, Frances Borkowski, married Henry Kerrison in Christchurch in 1881. They had at least 10 children. School records show that they went to at least five schools and Canterbury, and six in the Manawatū, as the family moved from Colombo Street in Christchurch to the North Island around 1892. Henry gave the school authorities addresses in Carnarvon, Sanson, Fielding, Bunnythorpe, Woodville and Palmerston North, where school records seem to stop in 1900. Te Tari Taiwhenua/ Internal Affairs does not seem to have a death record for a Frances Kerrison.

Thomas Borcoskie is buried in the Linwood cemetery with his son, John Thomas, born in New Zealand in 1875, the year after his elder brothers, Stanisław and Alfred, perished on the ss cartvale. With them is John Thomas’s wife, Annie née Gierszawski Borcoskie, who died aged 30.H-7

_______________

In 1939, Polish wives and mothers in Marshland would have been perplexed if not mortified if they had read Hughes’ conclusions regarding the “state of confusion which presides in many kitchens.”103 These farmers may not have had the pressures of the first settlers—draining the land, removing stumps, improving the soil, and getting the first crops in and to the market—but they were working farms, and Hughes admitted that the “wife, when finished with household chores, goes into the field if the season demands it to do her share of manual labour [and] the children are also kept busy in their spare time, weeding the crops.”104

Hughes seemed to struggle with his discovery that the “overwhelming majority” of boys did not progress to secondary school, but provided labour for the family farms, and took on their elders’ “deeply ingrained” work habits.105

“The general attitude of parents seems [to be] that the child is of more use to them at home. His chances of personal advance into a different sphere have been sacrificed to extract more and more from the soil and increase the production of wealth, to the detriment of culture.”106

The school’s teachers, however, embraced the fact that boys followed their fathers, and encouraged them to experiment with a view to what would be of use on their farms. An elementary agriculture course included experiments on onion cultivation and local soil samples, and encouraged the pupils to assess the best types of manure and the best variety of onion seed. Boys in pairs were given an area on the school grounds where they conducted their own experiments and calculated their own results, which resulted in lime, for instance, being “widely adopted throughout the district.”107

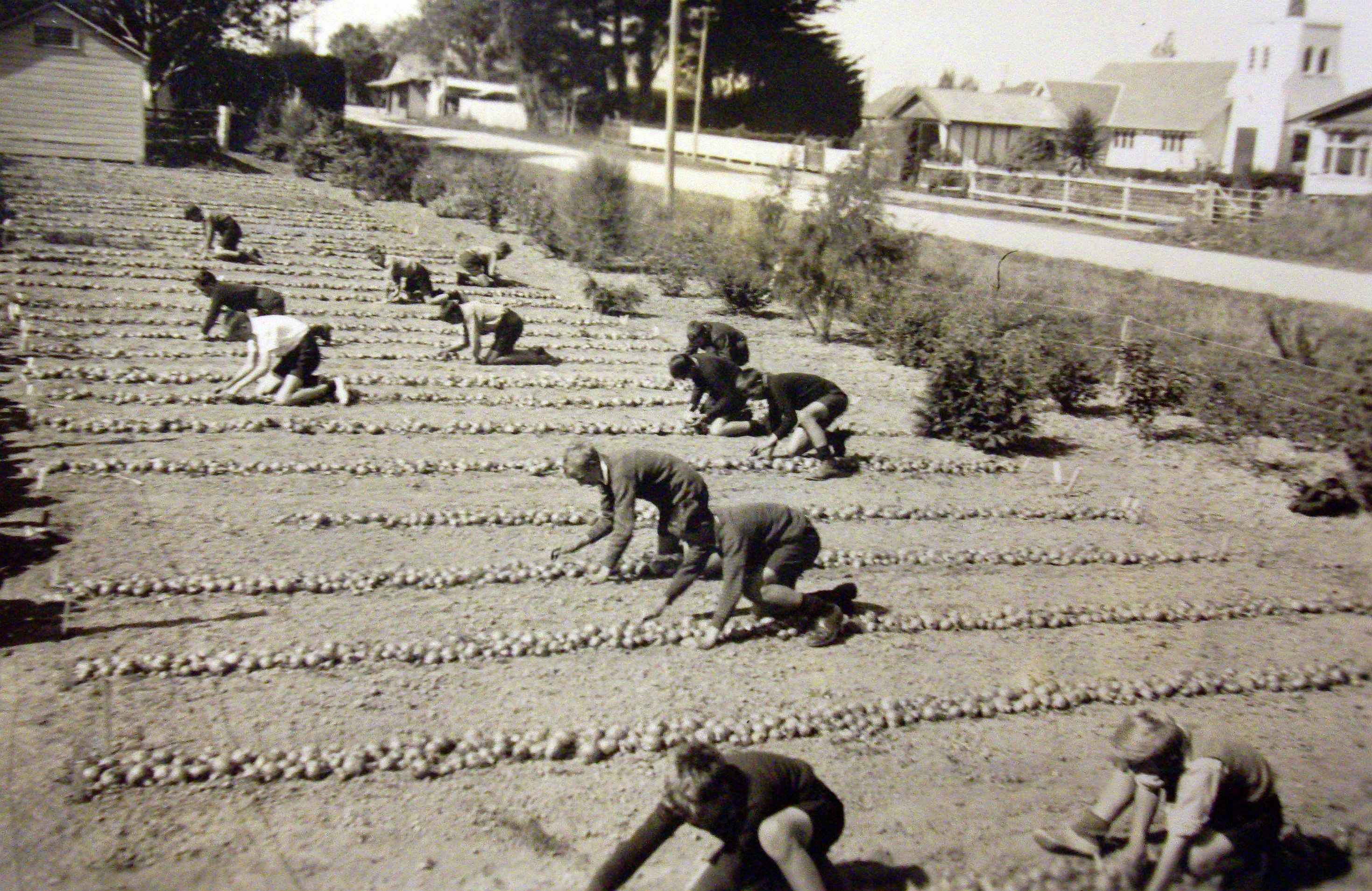

Hughes captioned this photograph of boys tending the school’s onion crop: “Education is Living.”108 They are mimicking what happened on their family farms from mid-February, pulling the ready onions by hand and laying them in rows to dry their tops.

Hughes interviewed the wife of the head teacher, but again did not name her, possibly because of her less than complimentary descriptions of people in the community. She said that their speech was “slack,” none having had the “benefits or the opportunities of secondary school education,” that their homes were “rather stodgy,” and that they had become “very conservative in their ways.” She conceded that many “hard-working” women still helped in the fields, and that they were “great supporters of the school,” but saw no leaders among them—although she held hope for the girls, whom she described as “a fine type considering their opportunity and background.”109

Hughes’ describing Marshland’s Polish settlers as “German Poles,”110 suggests he did not speak to any. If he had, he would have been under no illusion that the Poles left their homeland to escape its Prussian-partitioning and its German language, and were vehemently Polish.

_______________

The swamp’s early speculators correctly predicted that the land held agricultural potential. As it drained, the hidden forest remains emerged, and exposed peat that promised high yields—if it were not for the stumps.

Few farmers could afford the ₤40 to ₤50 an acre expense of removing the rising timber, and the surrounding peat prohibited burning the wood.111 Some of those on the boundaries of the swamp, such as the on the higher sections adjoining Hill’s Road and those with paddocks closer to the sea, decided to turn their land into dairy production rather than the intensive hand-labour involved with onioning, especially at harvest-time.

An extension of the St Albans-Papanui milk-runs developed in Marshland, was buoyed by the “… steady and growing demand for milk in the city… compared with the constantly fluctuating demand for onions…”112

Hand-milking prevailed on the Marshland milk runs (sometimes called milk walks), which relied on co-operation between farmers. During the off-season farmers sold their milk to those who needed to supplement their supplies.113

The rich peat soil in central Marshland, however, promised so much that farmers there persevered with the timber and stump removal, turned to market gardening, and developed the first premier onion growing region in New Zealand.114

Before they planted the onions, Marshland farmers “broke the land into cropping” with carrots, which had a supplementary market at the city’s tramway stables and the adjoining racecourse at Riccarton, 12 kilometres away. The farmers used bullock teams to plough the cleared land, and enriched it with stable manure that they collected and carried back after delivering their loads on a “tip dray along whatever roads that existed.” Carrots then sold for 10 to 15 shillings a ton.115

Onions demanded that fields received three ploughings, and then “grubbed with a tine cultivator.” If they did not spread artificial fertiliser, farmers ploughed in green crops such as lupins, black barley, or oats, and the stable manure. Before they had a chance to seed, weeds such as Shepherd’s Purse and sorrel were carried off the fields and burnt.116

Even with shelter belts, the north-westerly winds destroyed onions and other seedlings. Joseph Watemburg’s son William, born in 1906, remembered how the winds toyed with his father’s onion crops. They blew away seeds, pulled young onions out of the ground, and banked the soil against the farm fences.117

The earliest onion harvests were dried off, strung, and sold to local hotels and boarding houses. Demand increased through the local city markets. Stringing made way for “bagging and organised marketing,” which expanded the onion trade throughout New Zealand.

Onion growers in 1939 surround an onion grading machine in Marshland. Growth of an export trade made men like these “Onion Kings” but when “substantial quantities” still had to be imported, the government introduced regulations and a Marketing Provisory Committee for each island.118 Onions were usually bagged in the paddock in 100lb bags such as the one to the left of this photograph.

Farmers grew onions in the same ground for several seasons, and interplanted them with carrots, potatoes, cabbages, and parsnips.

After the Great Depression, from 1929, many of the farm labourers took seasonal jobs between November and June at the Canterbury Frozen Meat Works in neighbouring Belfast.119

Besides the neglected roads, the winds, the stumps, and the ongoing drainage issues, two diseases emerged in the market gardens: onion smut and yellow dwarf. In 1939, these diseases led to exports from Marshland being forbidden. Farmers co-operated in eradicating the scourges, and many gave parts of their land to the Department of Agriculture for experiments. The introduction of mesh bags preserved the onions and displayed them better.120

Export onions being loaded onto a truck ready for transporting to the Belfast Railway Station.121

By 1939, Marshland supported three types of farming—onion growing, market gardening and dairying—and one type of family, where all members helped get their product to market.

_______________

Wilfred Walter remembered several of the Poles in his neighbourhood living in a “close settlement” arrangement on a 20-acre property divided into four blocks:122

“Mr J Schomski [sic] lived on the paddock next to [McSaveney’s] road. His dwelling consisted partly of sod and timber… He reared a family of four, two boys and two daughters.” Walter remembered that the family later moved to Marshland Road. A fifth child, John Suchomski junior, was born in 1886.

“The next paddock was held by Mr C Rogal. He reared a big family, and it is still a wonder to me how he made both ends meet, to feed and clothe so many on only five acres of land. He was a wonderful worker and made the most and best of the place. He afterwards returned to a place on the Marshland Road now owned by Mr J Blackburn.

“The third paddock was occupied by Mr Albert Watemburg, a quiet and unassuming man. He was a most industrious person, and was a noted hand at ‘stumping the land.’ He left here to take a place on Lake Terrace Road… Subsequently he took over thirteen acres of land at the corner of Marshland Road and McSaveney’s Road. He lived in a small house, and he grew crops of onions and carrots… When the place with all the other properties in the district was offered for sale, Mr Watemburg became the owner of it. He then built a very nice house…”

Albert Rhoda took the “far paddock” in the block and shared a section of that with Jack Rock until the latter moved to Preston’s Road. Albert Watemburg’s daughter, Mary, then Mrs le Vavaseur, spoke to Wilfred Walter of Albert and Jack being brothers, and said that Jach had changed his name to avoid confusion with his nephew, John Rhoda.

Mary le Vavaseur’s recollections demonstrate the complexity of Polish inter-relationships in Marshland: In 1874, the cartvale carried seven members of the “Rhock” family—but their name was not Rhock. In Rytel, Pomerania, before the germanisation of Polish names in Prussian-partitioned Poland, their surname was Roda. According to parish records in Czersk, Albert Roda (33) and Marianna Szmaglińska (25) married on 27 August 1866. By the time their first children, Julianna, and Johann, were born in nearby Rytel in 1867 and 1870, Prussian authorities had changed their family name. Johann was the germanised spelling of the Polish Jan (the English John).

Ray Watembach, Albert Watemburg’s grandson and Mary le Vavaseur’s nephew, is an authority on the origins of Polish names in New Zealand: “Germans introduced an ‘h’ and changed it to Rohda, then Rhode. In New Zealand, officials followed an English girl’s name fashionable in 1874—a logical mistake for officials interpreting a Polish-accented ‘Roda’—and made it Rhoda.”

Albert accepted the misspelling, although the first two Rhoda births in New Zealand were recorded as Rhode: Anna in 1875; and Frank in 1877. Albert and Marianna’s next two children were officially recorded as Marie Rhoda in 1879, and Rosalyia [sic] Rhoda in 1881.

Wilfred Walter watched the Rhoda family move from the five-acre paddock to Walter’s Road, where Albert erected the first buildings. They later moved to a property on the corner of Hill’s and Kelly’s roads. Mrs Rhoda made an impression on the young Wilfred, but his assessment of her happiness at toiling may have been misinterpreted:

“Mrs Rhoda helped her husband in working the land, cleaning and harvesting the crops, and she was a wonderful worker in every other way. Everybody who knew her… spoke in high praise of what a great worker and settler of the district she was. She was never happier than when she was out in the paddocks working, and it could… be safely said it would be difficult to find another woman in New Zealand to equal her in this kind of work. Almost to her last days she was to be found toiling on the paddocks. She was equally as good as any man in tilling the soil and at harvesting the crops, which were nearly all root crops in those days.”123