The Dodunski-Schimanski Family

IT STARTED ON THE DANCE FLOOR

by Barbara Scrivens

Albert Schimanski arrived in Stratford in 1906 to visit his fiancée. Dance hall music made him pause as he walked from the railway station. He popped his head around a door, saw Martha Dodunska, and changed his plans.

Albert carried his “good suit” in his suitcase and was wearing his “second” clothes and “broken” shoes for his substantial journey from Christchurch. Martha saw him and asked, “Who is that man?”

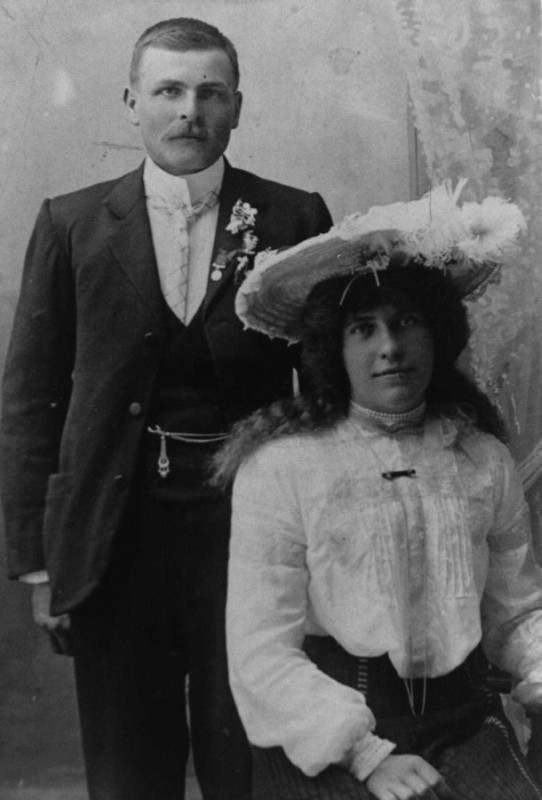

She did not have to wait long to find out. Fiancée forgotten, Albert abandoned his suitcase and spent the rest of the evening dancing with 18-year-old Martha. They married on 21 May 1907.

Martha told this story and many others to her daughter and ninth child, Thelma. That same evening Martha was herself betrothed to Anton Wiśniewski. Martha’s older sister Thelka was already married to the soon-to-be-rejected suitor’s older brother, Jack (John), and Martha’s brother Joseph was courting Anton’s sister Johanna. Martha could not face Anton herself and one Sunday after Mass gave his engagement ring to her youngest brother, Matt (Mathias), to return. Albert retrieved his own engagement ring and gave it to Martha.

“My mother said she was in town one day and met [Albert’s first fiancée] Martha Burkett. My mother was wearing gloves. She was wearing Albert’s ring and kept very quiet as Martha Burkett was talking about Albert’s promise to replace her ring to with a better one.

“I said to my mum when she was telling me this story, ‘Fancy wearing another girl’s ring.’ And she said, ‘Ah, but I got the man I wanted.’”

Martha kept her engagement photograph to Anton Wiśniewski, left.

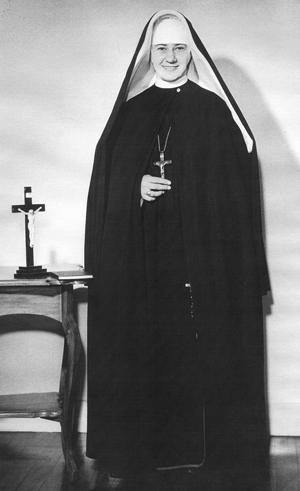

Thelma, now Sister Mary St Martha, recalls how when she was about 10 her father met Anton in Inglewood and invited him to their farm in Durham Road.

“He sat next to me on a wooden box, pointed to my mother, who was peeling potatoes for tea, and said, ‘I wanted to marry your mother once but instead she married that fool over there.’ And both my mother and father were chuckling away.”

If Albert had made no effort to dress for that particular dance Martha was the opposite. Her cousin Theophilus ran the dances in Stratford and for Martha, attending took three days’ preparation.

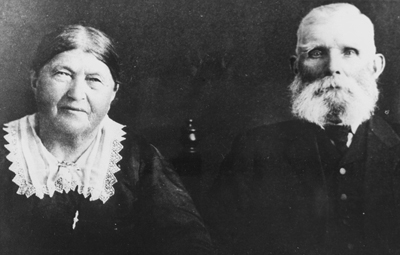

Martha Dodunska, the ninth of Apolonia and Mathias Dodunski’s 11 children.

“My mother lived on Durham Road. Her father would give her the horse and trap and she would travel down to Stratford, by herself as far as I know, and stay with uncle Theophilus and his wife Mary in Stratford. She’d travel one day, stay the night, prepare her dress and her hair for the dance the next day, and then the third day she would travel home in the horse and trap. That was her outing.”

Sister St Martha revised her opinion of her father when she gave a eulogy at a Schimanski family reunion in 1984 for what would have been his 100th birthday.

“As a child I’d often be ashamed of my father. His shoes were never shiny, unless I polished them. He always looked as if he was coming from work or going to work. He would go to town and he’d have a mismatching pair of trousers and a coat, and hardly ever wore a tie.

“I realised he was a good man, despite wearing mismatched coats and trousers.

“We were never hungry. We always had plenty to eat and he never wasted money. Some years later, I was collecting in Inglewood for the building of the convent and told people that I’m Albert Schimanski’s daughter. One man said, ‘Oh, I remember your father. He was a hard businessman but a good man.’ That was good to hear.

“Mum wouldn’t argue or query anything my father did. And I don’t think I ever heard him query anything my mother did.”

Sister St Martha’s earliest memories are of being surrounded by children, usually her nephews and nieces. Her older siblings grew up on farms in Marshland and, briefly, Darfield in Christchurch. The family derived their income through market gardening and ventures such as selling milk and stock.

When Martha’s mother, Apolonia, became ill Albert told his wife that if he could sell the farm they would move to Taranaki. The farm sold, the family moved, and Martha was able to support her mother before she died in May 1928. Mathias died 10 years later, aged 93.

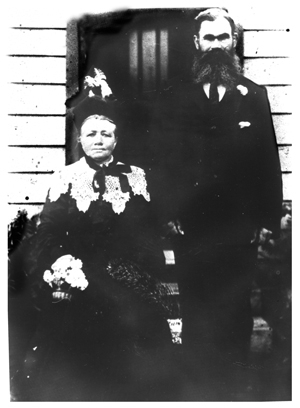

This photograph was taken shortly before Apolonia's death in 1928. She was 77.

_______________

Born Thelma Mary Schimanski in August 1929, Sister St Martha was 10 and walking with her mother in “town” when she discovered the existence of her oldest brother, Les, 21 years her senior.

“This smiling, good-looking man came up to my mother and I learnt that this was my big brother. He had children my age. My father came along and didn’t acknowledge the man my mother was speaking to. My father eventually said in a quiet voice, ‘Aren’t you going to introduce me?’ My mother laughed and said, ‘This is Les, this is your son!’

“Les had words with father and had left home when he was 15 or 16—gone off into the bush somewhere… and here he was a married man with children. His first job was in the Kaimanawa ranges spreading bait for rabbits. He had been working up at Karangahake gorge building a tunnel for the train. My sister Gertrude and her husband also worked there.”

Sister St Martha remembers her mother telling her father, “Sons follow their fathers. You had a row with your father and you ran away and now your eldest son has had a row with you and he ran away from home.” Fathers and sons reconciled in both instances. (Albert apparently left home at 14 to cut trees in the bush—then a common occupation for young men.)

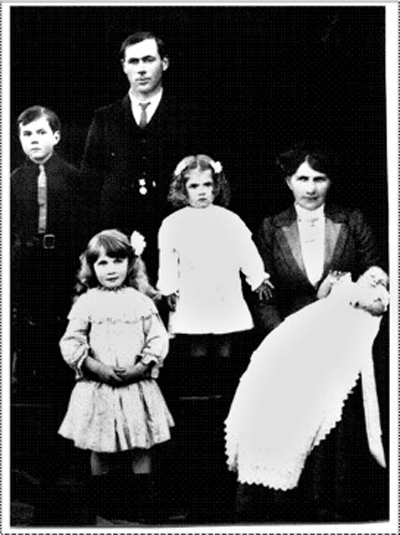

Albert and Martha’s second child, Gertrude, born in 1909, married Leonard Fischer the year before Thelma was born and lived “just up the road” from the Schimanski farm on Durham Road, Inglewood. They had three children Thelma's age.

“Because her children were my playmates, they called her ‘Mummy’ and I called her ‘Mummy’ and my mother was called ‘Grandma’ so I called her ‘Grandma.’” Neither Gertrude nor Martha corrected Thelma.

“I don’t think my mother ever complained about anything. She was a professional nurturer. There were always lots of children and she loved to play games with us. When I was quite grown up, she was still nurturing children who came to us in the school holidays. There were always lots of people around. Gertrude was more often in our house than in her own.”

After Gertrude came Theresa Pauline (1911), Victa Nicholas (1913), Philip (1915), Reginald (1916), Douglas (1920) and Ngaira (1922), all born in Marshland. Thelma and her brother Clifford were born at the Durham Road property, Clifford in 1933.

Albert and Martha Schimanski with their eldest children, from left, Leslie (Les), Gertrude, Theresa and Victa.

Thelma at three or four years.

“I was the official baby sitter at our house when there were little wee ones about. I was about five when Gertrude came home with a little baby girl and I had to sit down on the back step, put my knees together, hold my arms out as the baby was put in my arms. After a little while I just about threw her off and yelled, ‘She wet me!’ so they grabbed the baby. I have a deformed hip because I carried so many little ones on my hip from when I was only 10 or 11.”

Martha’s Sunday dinners had two sittings: The children had theirs in the kitchen at the three-metre-long table and then played outside, leaving the adults eating undisturbed in the sitting room.

_______________

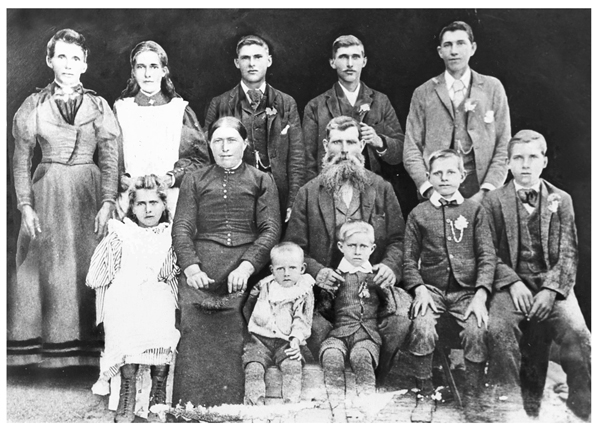

Martha, born in Inglewood in 1888, was the ninth of 11 Dodunski children who grew past infancy. Mathias and Apolonia (née Drozdowska), arrived in Wellington on board the fritz reuter on 4 August 1876. Mislisted under the name Duschminski, Mathias (Matheus) was 31, Apolonia (Pauline) 26, Franciszka seven and Franciszek two. A note in the family tree showing two dead, unnamed infants born in 1871 and 1873 explains the five-year age gap between their children.

According to family story, a Dodunski infant died at sea but, as there is no mention of one on the passenger list. A Pomeranian births, marriages and deaths index records the death of six-month-old Pauline Doduńska registered in Subkowy in 1873, but has no birth record. It also records Augusta Paulina born to Mathias Doduński and Paulina Drozdowska in Tczew in 1876, but no death record under her name. That timing, and her absence on the passenger list, suggests she may have died on the way to Hamburg, or soon after.1

The Doduński families lost the Polish diacritic mark when they immigrated to New Zealand.

Their mis-spelt name on the fritz reuter, Duschienski, probably came about because fellow passenger Barbara Duschenski (Polish spelling is Duszyński) was Apolonia’s younger sister.

Mathias and Apolonia Dodunski with their family, about 1895. The children are: back, from left: Franciszka, Thelka, John, Franz and Albert and front: Martha, Mathias junior, Anton, Paul, and Joseph.

Mathias, was the eighth and youngest child of Mathias and Katharina (née Lipszczonka/Lipinska) Dodunski of the Gręblin area in north-western Prussian-occupied Poland, and fewer than five kilometres south of Subkowy.

Three years after the Dodunski family arrived in New Zealand, they were followed by Mathias’s sister Barbara (44), her husband, Martin Potroz (54) and children Maria (18), Thomas (16) and Barbara (9), who arrived in Wellington via the hudson. As “Colonial Nominated Emigrants” they did not have to suffer the ignominy of not being allowed to disembark, as happened to the fritz reuter passengers, which included Barbara and Martin’s eldest son, Anton Potroz (24), his wife Maria (née Zimmerman) and 18-month-old Jakub, and his sister, Apolonia Neustrowski (née Potroz, 26), her husband August (26) and surviving children, Marianna (5) and Johan (2).

The hudson sailed from Plymouth with 250 immigrants, the Portoz [sic] family the only Polish ones. By then, Mathias’s and Barbara’s older brother, Michael, was the only living member of their family left in Poland.

Mathias wrote to Michael, enthusing about life in his new country. In 1883 Michael followed his siblings with his own family (wife, Katarina, and children Barbara, Joseph, Francis, Theophilus, Agnes, and Johann) but the new colony did not match up to Mathias’s description and Michael apparently “never forgave” Mathias for encouraging him to leave his European roots.

Michael Dodunski’s family disembarked from the british king in Taranaki with his sister-in-law’s brother Franz Drozdowski, his wife, Marianne and children Julianna, Rosalie and Franz. Again, the Dodunski and Drozdowski families were the only Polish ones on board. Two other Drozdowski brothers, Anton and Józef, had brought their families over in the shakespeare in 1876 and settled in the Inglewood area.

_______________

Albert Schimanski’s parents, Christianus and Louisa née Nikel. Albert was their youngest child, and the only one born in New Zealand.

Albert Schimanski’s parents, Christianus and Louise (née Nikel) Schimanski, two step-brothers, and four siblings arrived in Lyttleton aboard the firth of forth in February 1883. The barque left London on 7 November 1882. Compared with other immigration vessels, which carried hundreds of immigrants, this one had few.

Louise’s sons Martin (16) and Michael (13) Szaluga/Sharlick, from her marriage with their late father, were counted among the adults. With them were Julia (9), Augusta (5), Mary (3), three-week-old John. Like Doduński, the Polish spelling of Szymański did not last the voyage.

John gained mention in the press on 6 February 1883:

The vessel contributes to the population of the colony 31 souls, equal to 25 adults. There was a birth on January 18th, Mrs Schimanski being delivered of a son, both doing well.2

Albert, born a year later, does not seem to appear on the New Zealand registry of births. A Christchurch post office fire had consumed his birth certificate, something he only discovered when he applied for his pension and was initially denied it. Albert argued that if he was not granted his pension, he should get his taxes refunded.

_______________

Les was not the only older sibling to appear suddenly into Thelma’s life.

“I was about five and was playing outside one day when this lady came in—Theresa. She said I was a grubby little girl. She was really grand. Her hair was done, her hands were nice and clean and she had on a lovely long ballerina dress. She had been working in Australia with her girlfriends and came home for a holiday. She was a career girl and didn’t get married until her early 30s. She worked in hotels all over Australia and New Zealand.

“Gert told me that the first thing she did when she came home from school in Marshland was make tea and some sandwiches and take them to Mum and Dad weeding the vegetables down in the paddocks, and collect Doug and Ngaira who weren’t school age yet. She would bring them home and start washing dishes. There were the breakfast dishes and the lunch dishes, so the bench and to be cleared before she could start getting something ready for tea. Vic used to help—but not Theresa.

“… the Polish children often missed school because they were needed at home to milk cows or look after calves or children who were ill.”

“I remember Gert telling me that Theresa always had to get her homework done. That was her priority—seeing to her homework and mending anything that needed mending, like stockings. She always had mended stockings whereas Gert never had time to mend hers. If there was a hole in the toe, she had to turn them down so that nobody could see. Ngaira was just a toddler and Gert was only 14 or 15, but she made sure her baby sister had everything she wanted and the boys weren’t teasing her or anything.”

Thelma Schimanski went to the same school as her mother, in Durham Road, where the roll peaked at 36. As a child Martha lived on Norfolk Road, and got to school by cutting across the paddocks and the Maketawa River. She was absent for the 1898 photograph below.

From left to right, back row: Beatrice Bridgman, Anne Cheevers, Anne Soul, Ada Bridgman,

Ivy Mischefski, Gladys Simpson, Anne Kemp, Mary Christensen.

Middle row: Fred Mischefski, Andrew Dodunski, Felix Mischefski, Albert Laurence, Mathias Dodunski junior, Dick Richards,

Norman Bridgman.

Front row: Agnes Mischefski, Gladys Bridgman, Martha Christensen, Anne Richards, Dorothy Simpson, Evelyn Laurence, Gladys

Langly, Lil Dombroski.3

“My mother went to school until Standard Three or Four. My father was the same. They were probably slow at learning because their first language was Polish. You were in a Primer class until you had been at school for two years, and then you would go into Standard One—if you knew your reading and your numbers. Years later the mother of one of my friends told me that the Polish children often missed school because they were needed at home to milk cows or look after calves or children who were ill. They would get into trouble at school and one of the teachers called them ‘dumb polly-wollys’ because they found the English language difficult. By missing school they would get even further behind.

The same surnames appeared in the 1910 Durham Road School photograph:

From left to right, back row: Monica Dodunski, Eileen Corney, Percy Dodunski, unnamed

child, Joe Mischefski, Fred Marsom, unnamed child, unnamed child, unnamed McParkland, Andrew Mischefski.

Second row: Ellie Brooking, Phoebe Goldfinch, Mary Mischefski, Fred Mischefski, unnamed McParkland, Norman Bridgeman, Frank

Buckthought, Roy Marsom.

Third row: Myrtle Marsom, Kathleen Corney, Neta Langley, Ethel Dombroski, Madge Simpsom, Dolly Mischefski, Katie Mehrtens,

Doris Mehrtens, Gladys Rickard, Ethel Corney, Ella Dombroski.

Front row: Paul Mischefski, Stan Wisnewski, Leo Dodunski, unnamed Goldfinch, Ernie Dodunski, Francis

Dodunski.4

“My grandfather Christianus Schmanski couldn’t read or write, and any application papers, he would sign with a cross, and the same for great-uncle Matt Schimanski. My father’s step-brother, Uncle Michael, was going to school one morning in Marshland and another market gardener called out to him to come and help him do some weeding so he put his schoolbag down and didn’t go to school—but the Marshland headmaster and his wife held night-classes, so they learned to speak English by going to those.”

Years later “Uncle Michael” [Sharlick] called on his nephew Victa, on his way home from school, to help him plant cabbages. (See Sister St Martha’s story, early childhood in the 1990s under marshland–family stories.)

“I’ve got some official papers of Michael’s where he signed his name so I know he learnt to read and write. My father used to read the newspapers. I never saw him reading books, but he’d read the newspaper, and when I came home from school with school journals, he would read those. We had about two shelves of books that my brother Reg won at school.

“I loved reading. The teacher used to sit at her table and the primers would come up with their reading books while she was marking written work that the standards were doing. I was reading the book and she turned around, gave me a hard look, then she closed the book. ‘Now read it,’ she said. So I kept on reading it. I knew it off by heart so she wasn’t giving me any challenges. A Miss Thomas, her name was. She should have given me a harder book.”

_______________

Sister St Martha fondly remembers the farm where she grew up, picking peas in its large vegetable garden, and her father giving her a tennis racket, saying he would give her a penny for every white butterfly she caught or killed.

“My father had sheep on the farm. They used to follow the cows, kept the paddocks very clean and we often had sheep meat to eat. I think one of the nicest things I’ve ever eaten is new potatoes and green peas out of the garden, and mutton chops.”

“My father would say, ‘Go and get a big dish from your mother.’ This was when they hung the sheep from the rafters of the implement shed after they killed it. It was strung up, skinned, then cut up on the kitchen table. Nothing has ever tasted like the sheep meat killed on our farm—so tender.

“There was a big tub of saltpetre brine where they would soak a pig and hang it up to dry in our sitting room on hooks above the open fire. We always had legs of pork hanging.

“We had lots of goats on the farm. They ate all the rubbish, ferns, and blackberries. We often ate goat. They’d kill a goat, skin it and nail the skin on the cowshed doors so there was always a skin hanging, drying out and every bedroom had a goatskin mat by the bed and one by the window or the dressing table. They were very, very thin. We’d have lino on the floor and then we’d have the goatskin. We had lino in the kitchen and there was lino in the sitting room until my mother had carpet put down.”

After the family moved from Christchurch, Albert passed the major farm responsibilities to his sons, but kept the vegetable garden and two acres under potatoes. He travelled around the area delivering potatoes and other vegetables and had a regular customer who had a shop in Manaia on the southern Taranaki coast. Albert always came home with apple boxes filled with fruit unsuitable for sale.

“It was called ‘speckled fruit’ because there was either a bruise or a rotten speck on it. Gert would cut up the oranges and apples. We used to buy lots of apples but we didn’t get many oranges or bananas or more exotic fruit… and I can remember standing on one foot, then the other, and enjoying this juicy orange.”

Victa eventually married and left home. Douglas was still at school, so Philip and Reginald shouldered most of the responsibility for the day-to-day running of the farm, milking the 60 cows, ploughing, hay-making, and stumping.

_______________

In about 1932 or 1933, Reg carried young Thelma on his shoulders as he inspected damage on the farm after a flood. She still remembers the Ngatoronui river “high and angry looking” as it raced through their property and washed away their bridge.

“His leg could have been cut off with a pocket-knife but nobody had even a pocket knife…”

One Sunday afternoon years later, Albert and his sons joined other farmers in the area inspecting the first new bridge built farther along the same river on the neighbouring Dombrowski farm. The bridge spanned a section with high banks. As Albert scrambled underneath to take a closer look at the design and engineering, the structure gave way.

“The bulldozer or tractor that was on the bridge pinned him to the bank. His leg could have been cut off with a pocket-knife but nobody had even a pocket knife. He was carried to the top and taken by ambulance to the New Plymouth Hospital. The leg was taken off above the knee and after that Dad had a wooden leg.”

(The three rivers between Durham Road and Dudley Road Upper do not appear on general maps, but Sister St Martha drove to the markers to confirm they are the Ngatoronui, the most southerly and closest to Durham Road; the Ngatoro, south of Dudley Road Upper; and the Ngatoroiti in the middle. All flow into the Waitara river and the Tasman Sea.)

“On the farm, the boys learnt by their mistakes and Dad kept an eye on them. Dad took more notice of Doug… always a nuisance to the older boys, always getting in their way.”

“I rode my bike to and from school in Inglewood. In winter, I often took the same train that the Norfolk Road children used. It made me late for school, but Dad would be in town to take me home.

“One day, he fetched me in his ‘breaking in turnout.’ He had a young horse and a small, low dray with extra-long shafts for the horse. I took a school friend to show her, and was patting the horse when my father came into the parking lot and very quietly called to me to ‘get away from the horse.’ I had forgotten that this one was in the process of being broken in.

“Nothing went wrong, and Dad and I went home, the horse obedient to Dad’s training. He was well-known for the horses he trained and sold, his hobby after he moved to Taranaki. Years later, I was told: ‘If your dad said the horse was a leader [of a six-horse team], it was a leader.’”

Douglas Schimanski inherited his father’s knack, and made his living from horses. At 19, he bought a paddock with his own house—two rooms and a lean-to—in Inglewood through earnings from ploughing and breaking-in horses. Housework was not a priority and occasionally, Doug asked Thelma to wash the floors as he swept cobwebs from the ceilings.

_______________

Thelma hated going barefoot on the farm and wore boots or gumboots to protect her feet from mud. She avoided the swampy areas farther away from the farmhouse and discovered a particular path where she could “jump from one log to the next.”

“It didn’t occur to me then, but they were railway sleepers, part of a railway track that used to take the logs down to Brown’s Mill in town. When the land was first cleared the logs were taken down by temporary railway lines, like the one on our farm, made before we arrived.”

Thelma loved animals. One day her mother returned from one of her visits to her sister-in-law Mary Rogal (née Schimanski) and her family in Christchurch with a Pomeranian stray.

“The dog hopped around on three legs and the Rogal boys used to shoo it away. My mother brought it up with her on the train and on the ferry and she said it was quite quiet in a little box. Nobody knew it was there and she gave it a little bread or a sandwich or something on the train and brought it home as a present for me.”

“The Inglewood parishioners didn’t like the idea of their convent being sold so they bought it again—they built it to start off with and then they paid for it again.”

Thelma and Clifford also had a pony each, her brother’s smaller but with “good hooves.” Thelma’s pony did not impress her, its foundered hooves a result of pulling carts.

“We went to the Stratford agricultural show once, and why my pony was taken I don’t know. My brother rode it because I wouldn’t. They came last because it couldn’t race. I asked my mother to sell my pony so that I could buy a piano.”

Thelma was saving for the instrument by sweeping the Durham Road School every afternoon before she went home, a job she inherited from Ngaira, who was six years older. The Shimanski family was considered the school’s caretakers.

“At the end of term my mother would get down on her hands and knees and scrub the schoolroom floor… a big job. I took over the sweeping when I was about 10 or 11. The pay was £12 a year. My mother took half the money and gave me the other half. I never saw the money, my mother held it.

“I found out that somebody was moving down to the South Island and they had an old piano they were willing to sell. Then I dragged my mother along to the convent to ask Sister if I could have music lessons. Mum nodded her head.”

The convent’s original wooden structure in Inglewood needed rebuilding and became known as Forrestal House, named after the parish priest who collected money for the project. After the sisters vacated it they gave the property to the bishop, whose financial advisers apparently decided they didn’t need the building and put it up for sale.

“The Inglewood parishioners didn’t like the idea of their convent being sold so they bought it again—they built it to start off with and then they paid for it again. That building is now known as Forrestal Lodge.”

_______________

In Marshland, the family went to Mass in a horse and gig but in Taranaki, they drove to church in style—an Essex with canvas sides and celluloid windows. Martha and several of her older children were involved in various parish activities and associations connected to the Catholic church in Inglewood, and only an infectious disease such as measles prevented a Schimanski from missing Mass on Sunday.

“… my mother and I sat down by the fireside… and she’d tell me stories about her mother and what she did when she was a child… and how the family lived while she was growing up.”

“Once, somebody had the measles. The men went off to church and all the children were in bed in the front bedroom. My mother and Gert had us all saying the rosary. We always said the rosary at night-time. We would have our tea and, if someone was going out to the pictures or to a dance, we would leave the dishes and say the rosary in the sitting room, so they were praying before they went out.

“I kept her company while she waited for her children to to come home. We sat down by the fireside—I can’t remember a time when there wasn’t a fire in the sitting room—and she’d tell me stories about her mother and what she did when she was a child. Mum would tell me about her mother and how the family lived while she was growing up. I loved listening to her.

“When I was in the convent, we had an elderly Polish lady who used to work in our laundry and when my mother visited me, I took her around to meet this Polish lady so they could talk in Polish because this lady didn’t speak English. When the Polish children came to the Pahiatua camp [in 1944] (See the pahiatua refuge pages under the war immigrants section.) my father went down with a number of other Polish men to visit them, and their elders came up to talk to the Inglewood parishioners. They were speaking in Polish and I said to my mother, ‘Do you understand everything he’s saying?’ She said, ‘Yes, but I think that we’ve been in New Zealand so long now, we speak a pidgin Polish.’

Sister St Martha believes her mother was doing herself a disservice and was merely using a different Polish dialect. Like the hundreds of other Polish settlers who arrived in New Zealand in the 1870s and 1880s from Prussian-occupied northwestern Poland, the Schimanski family spoke the Kaszubian dialect. The 838 Poles who arrived in 1944 were from eastern Poland. The Schimanski family was one of many that hosted children from Pahiatua during school holidays, the two Polish boys receiving Schimanski hospitality the same age as Thelma’s younger brother, Clifford.

The shun had nothing to do with bloodlines but everything to do with speaking a common language.

“A trainload of children arrived with notices around their necks with the names of who they were allotted to. They couldn’t speak English and they just got off the train and stood on the platform.

“It was night-time and we had to recognise the names of these children who were coming to us. They had great big trousers on that went half-way down their calves, and their coats were too big.

“One evening my father had a map of the world out and he was talking to them about where they had been and they were showing him and I remember him looking up at my mother in surprise and saying, ‘It’s not the Germans the Poles hate, it’s the Russians,’ who were very cruel to the Polish people and the Polish children in Siberia.”

Several of the elderly settler Poles living in Inglewood never learnt English. Sister St Martha believes they became ‘old’ quickly because they worked so hard. Her mother visited them regularly, one an aunt from the Drozdowski side of the family and another, one of the older Pahiatua refugees who made her home in Fitzroy, New Plymouth. A doctor once asked Sister Mary St Martha to visit a particular Polish woman, mistakenly thinking that being of Polish origin, the nun would be accepted. She was not. The shun had nothing to do with bloodlines but everything to do with speaking a common language.

_______________

Once the immigrants were allowed to disembark the fritz reuter in August 1876, Mathias and Apolonia Dodunski and their two children transferred to the ss taupo, and sailed north to New Plymouth with 48 other Poles. They were housed in the former soldiers’ barracks on Marsland Hill and given rations while they looked for jobs. The group was mentioned in the 19 August 1876 issue of the taranaki herald:

THE GERMAN [sic] IMMIGRANTS landed on August 16, for whom the immigration Agent (Mr. W. K. Hulke), immediately interested himself in procuring employment. Of the number who arrived, all the single girls have been hired, as also two or three married people with families. Some of the single men have been offered engagements, and others are still open to offers. Several of them also tendered to clear the 106 acres of land at Omata, advertised by Mr. Courtney, but were not successful, although tendering to do it at £1 per acre, which is considered to be a very fair price. This at all events shows that the men are willing to work if work is to be obtained, and to do it at a low figure. The Germans [sic], we hear, are delighted with the quality of the soil.5

The work was all done manually and after every bridge they finished they had their photo taken.

“The Poles who came in 1876 built bridges for the railway line in Taranaki. My mother had photos of her brothers Bert, Joe and Paul with other workers standing with their hats on, their waistcoats on and shovels in their hands. The work was all done manually and after every bridge they finished they had their photo taken. They always seemed to wear waistcoats. They bought a suit and wore it for best and wore the old suit trousers and waistcoat to work.

“When grandfather [Mathias Dodunski] bought his first piece of land in New Zealand, 10 acres on Norfolk Road, he had to cut the bush down in order to put up a house. The family story was that they lived in a ponga house in Inglewood for 10 years while he did contract work building bridges and the first ponga house he built on their own land had a canvas roof instead of a ponga one.

“That first ponga house was on James Street. When the Poles came over, the English called it German Street. Some Poles objected to that and they changed the name. Grandmother and grandfather Dodunski lived there with two children and a baby.”

Mathias Gabriel Dodunski’s name appears on the deed papers of 11 properties. The first two, a town property in Standish Street, Inglewood, and 53 acres in rural Durham Road, were bought in 1878, two years after he arrived in New Zealand. As well as the 10 acres in Inglewood, the return of the freeholders of new zealand, published in 1882, shows Mathias Dodunski had 67 acres in the “county” of Taranaki. Between 1884 and 1900 he bought nine more properties in the area, another house in Standish Street, another rural holding in Norfolk Road, and six in Durham Road.

“To come to New Zealand and find they could actually buy their own land… they were in a frenzy to purchase land for themselves and their children.”

_______________

Polish weddings in Taranaki were well-attended social outings where guests contributed by bringing plates of food. Mathias and Apolonia Dodunski hosted their son Albert's wedding in 1905 when he married Frances Schrider (spelt Schreder in the marriage records but also Schrieder, Schroder, Schieber and Schrader ).

Guests at the Dodunski-Schrider wedding gathered for the record on the veranda of the Dodunski's Durham Road farmhouse. Then, 17-year-old Martha, the bridesmaid on the left, had not yet met Albert Schimanski, and is standing next to Anton Wiśniewski.

The main wedding party:

From left, Apolonia and Mathias Dodunski, bridesmaid Barbara Schrider sits in front of Joseph Dodunski, the groom Albert

Dodunski and bride Frances Schrider, second bridesmaid Martha Dodunski seated in front of Reverend Father Long, and the

bride's parents, Bertha and Robert Schrider.

Photographs such as these became helpful to Sister St Martha when she started delving into her family history after her mother died in 1973.

“I used to visit the Kuklinskis in Inglewood and always came in the back door. One time I entered through the front so saw the back door closed. Hanging behind that door was a photograph nearly three feet high of this old man with a beard and I said, ‘Who’s that?’ They said, ‘Oh, that’s grandfather Kuklinski.’ And I said, ‘He’s in Uncle Bert’s wedding photo.’” [Jakub Kuklinski arrived on the fritz reuter in 1876 with his wife Barbara. He was 28 and she 33.6]

Sister St Martha’s record book of notes and mementos included a photograph her Uncle Bert’s wedding guests, taken at her grandfather’s Durham Road farm. As thrilling as it was to put another name to a face, even more satisfying was the Kuklinskis’ ability to identify several others in the photograph—their entire family attended the wedding.

“He was one of the few Poles… who could read and write and was a self-made lawyer. He could talk the legs off an iron pot and if any of the Poles were lost in the English system… they would go to him… ”

“The Poles kept to themselves in those days and they got to know other Poles. They arrived speaking a funny language, didn’t learn very well at school, and didn’t dress very well because they didn’t have much money. They were different from the English. When I went through school records, I saw few Polish names, and those would only be there for a few years. Their families needed the children to work on the farms.

“Sister Frances (née Lehrke) told me that when she wanted to join the Sisters of Our Lady of the Missions her father asked her to come home because she worked like another man on the farm. He told her he would have to sell the farm if she didn’t return because his sons were too young, and he couldn’t manage on his own.”

“Mr Lehrke was an educated man. His father was schooled by a parish priest who had found this orphan boy wandering the streets [in Prussian-occupied northwestern Poland] and took him in. He was one of the few Poles who came to New Zealand who could read and write and was a self-made lawyer. He could talk the legs off an iron pot, and if any of the Poles were lost in the English system of exploitation, or taken to court, or needed a lawyer, they would go to him, and if he went to court, he never lost a case—he’d talk himself out of it. I often went with my mother and father to visit old Mr and Mrs Lehrke when they lived in Eltham.”

The old Lehrke house in Eltham, the frontage unchanged in 2015.

_______________

The first in her family to go to high school, Thelma attended the Sacred Heart Convent in New Plymouth. Although she had specifically asked to board, she soon missed home and left in 1943. Again cocooned on the farm, the war raging in Europe and the Pacific remained distant to her. New Zealanders had ration books, but she does not remember hardship.

“We had a vegetable garden and we had meat in the paddocks. Petrol was hard to get but my father was very good at finding an alternative. By then he had his wooden leg and already had his mechanic friend fix up the car so that he could use one leg to drive. When petrol was rationed, Dad got the mechanic to put a gas burner on the side of the car so it needed only a little petrol to start and then the gas burner took over.

“Dad could go to town whenever he felt like it. He would buy and sell horses or dogs. He used to train dogs. We had a lovely Border Collie called Nell and she had lots of pups. I was watching them once—she was training the puppies herself. She would see the cows, and ran out after them. All the puppies would run after her. They knew they had to chase cows.

“Once, a dog was returned. The man said the dog was no good. Dad knew it was a good dog. I knew it was a good dog and I was only a child.

“One afternoon the boys were doing something on the farm, and they were late. Dad said to me, ‘You go down and bring the cows in and have them up in the shed.’ He called out after me, ‘Take the dog with you.’ So I took the dog and I was standing by the gate counting the cows and I picked up a stick, just a short stick, to help me count the cows. The dog took one look at me, put its head down, tail down and went home. When I got home, I said to Dad, ‘The dog went home.’ And straight away Dad said, ‘Did you have a stick in your hand?’ And I said, ‘Oh yes, I did, counting the cows.’ And he said, ‘That dog’s been beaten.’”

Thelma’s first job after leaving school was helping her brother Reginald milk cows on a farm farther down the Durham Road where he was a sharemilker.

“One milker with 60 cows wasn’t enough. You need somebody to help bring the cows in, tie them up, change the cups… so I went down to help him and that was all right but then it was hay-making time, and I was expected to help with that too.

“It was dark when I finished the milking and Reg was still cutting hay. I still had to feed the pigs. The pigsty was up on the hill away from the cowshed and I couldn’t walk up that hill—I was so tired… Cows, hay, I'd had enough.”

“In those days, half a dozen farmers would arrive to help tedder the hay, put it in rows, sweep it up and make a haystack. You needed two people on the haystack, one on the grab, one on the horse that pulled the grab, one on the ropes that activated the grab. The grab came down, you had to put the grab into the hay and close it, then the horse pulled the grab to the stack and the person on the ropes guided the grab so it would go where the men wanted it to drop. You pulled the rope, the hay fell out and then the (usually) two men on the haystack would spread the hay out in a tidy way, and so they would build up the haystack.

“I was usually on the horse, leading it forward and backwards. Once I was on a tedder, but something went wrong, and I was yelling. I couldn’t work out what I had to do, and the horse wasn’t taking any notice of me, so one brother came around to see what was going on because I was making such a lot of noise and he said, ‘That’s right, yell your head off and somebody will come to your rescue!’ I could manage the tedder until something went wrong but usually, I was around the stack, either on the rope or on the grab or on the horse. The horse was more my ability.

“When that paddock was done, the workers would move to the next farm or whoever had hay cut ready, so the farmers helped one another.

“One particular day I had milked the cows in the morning, then went down to help in the hay paddock, and then had to milk on my own in the evening because Reg had to cut the hay so it would dry out for the next day. It was dark when I finished the milking and Reg was still cutting hay. I still had to feed the pigs. The pigsty was up on the hill away from the cowshed and I couldn’t walk up that hill—I was so tired. I went back to the house and Reg’s wife, Cleata, had my tea ready. I said I didn’t want any tea and I went to bed. It got to the stage that I couldn’t sleep because I was overtired. Cows, hay, I’d had enough. The next day I went home, and Reg got the boy from across the road, Neil Gable, to milk for him.”

Thelma helped Reginald again a few years later when he had a farm in Rahotu on the coastal side of Mount Taranaki. By then he had two children and promised Thelma there would be no hay-making. She helped him on the farm and milked the cows until again she decided to leave.

…taking guests a cup of tea and a piece of bread and butter at 7 o’clock in the morning was a pleasure compared to being in the milking shed at five.

“Reg was paying me so I could afford a taxi. I went to the hotel in Rahotu and stayed there the night. He didn’t know where I was. He would have been upset. I didn’t care and I took a bus in the morning to New Plymouth and got a job in a hotel. There were lots of jobs about in those days because there was a shortage of workers in the war so it was as if I had the world at my feet.

“I arrived home and Reg was there. I suppose he was telling my mother I was missing.”

Working hours at the White Heart Hotel in New Plymouth suited Thelma much better than those on a farm. As a housemaid, taking guests a cup of tea and a piece of bread and butter at 7 o’clock in the morning was a pleasure compared to being in the milking shed at five. She helped serve breakfast and then cleaned the rooms.

“You were in charge of a certain a number of rooms. You made the beds, swept the floor, vacuumed, dusted, put out clean towels, served in the dining room for the lunch and you had the afternoon off from half past one to half past five. You came back and got ready for dinner, served the dinner and you were free at 7 o’clock. You had proper hours and time off. You even had whole days off and could go visiting.”

Thelma appreciated the hotel providing lodging, and its kitchen providing meals. She moved from one job to another, never staying longer than 10 months. By then, she would be longing for the comfort of the Durham Road farm. She worked at two accommodation venues on Mount Taranaki, the second at the Dawson Falls Mountain House. She declined a job at a Waikaremoana holiday resort after Gertrude convinced her to move to Napier, where Gertrude and her family were then living. Thelma worked at the Grand Hotel in Napier and one opposite the post office that she remembers as being the Colonial.

Gertrude later referred her youngest sister for a job as a home aide. The work involved helping families with young children while the mother was recuperating after a stay in hospital, but housekeeping for a retired solicitor and his wife, a Mr and Mrs Humphrey, in the up-market suburb of Bluff Hill in Napier suited Thelma better.

_______________

“My mother didn’t take me to a shop to buy a dress for me. She’d say there were dresses hanging up in the wardrobe, see if they fit.”

Previously, whenever her three sisters visited the farm, Thelma asked them to sew for her. During one of Gertrude’s visits Thelma, aged about nine, was wearing a striped pinafore:

“She told me to turn around. She put her fingers in at the top and split it down the back. I was in tears but Gertrude knew the fabric was perished and said, ‘I wore that when I was your age.’”

Because she did not always have her sisters visiting the farm a growing Thelma faced the sewing machine herself.

“My mother didn’t take me to a shop to buy a dress for me. She’d say there were dresses hanging up in the wardrobe, see if they fit. She had shown me how to use the sewing machine—a treadle—by mending sheets. I’d made a pair of pyjamas for my teddy bear, so I thought I knew how to use the machine.

“My first major alteration was on a particular dress I was getting too big for. The material was a soft blue flannel. I cut off the collar and put it around the waist and I cut off the sleeves and made a pinafore. I think I might have put the sleeves down the side to make it bigger. My mother was quite cross when I started cutting up that dress. She said, ‘What are you going to wear now? If you ruin that, what are you going to wear?’ But once I finished and put it on my mother smiled and said, ‘Oh, that looks all right.’”

In Napier, when Thelma asked Gertrude to sew for her, Gertrude said, “Make it yourself. All you need is a sewing machine, some pins and material.” Thelma said she had a complicated costume in mind. Gertrude suggested sewing lessons.

“I went to a dressmaking class and when I showed the tutor what I wanted to make she said, ‘Oh you can’t make that first, the first thing you have to do is make something simple like a petticoat or a nightdress.’ I didn’t want to make a nightdress or a petticoat.”

When Thelma told Gertrude that the sewing tutor had agreed to draft a pattern for the costume she wanted to make, Gertrude said, “That’ll cost you something.” Thelma cancelled the pattern order, went back to her rooms at the Humphrey's and started making her own pattern.

“Oh, dear, get a taxi. Don’t make a fool of yourself on the bus.”

“I pinned paper around a coat I had and cut out my own pattern. When I had sewn it together, I asked Mrs Humphrey if she would mind fitting it on me. I put it on inside out, she put the pins in, and I sewed it up. I went to a shop in town and asked them to do the buttonholes and then I sewed the buttons on. I rang up my sister and said, ‘I’ve finished my costume. I’m coming out on the bus wearing my costume.’ And she said ‘Oh, dear, get a taxi. Don’t make a fool of yourself on the bus.’ I went on the bus and I walked into my sister’s. She was at her sewing machine and said, ‘Turn around.’ I turned around and she said, ‘Don’t you ever come to me and ask me to make you anything again, ever!’ The only fault was that I had put two of the buttons too close together.”

The last secular job Thelma had was at a boys’ collegiate school in Whanganui where she worked in the dining hall. A tradition she found odd was that for the evening meal, the masters, who came into the dining hall half an hour after the 300 boys, had to be summoned by ringing a bell in the middle of the hall.

“I went in to ring the bell for the masters and there was dead silence in the dining room—all the boys turned around to look at me. I never rang that bell after that. I went and told the colonel in charge of the kitchen that I was not going to ring that bell anymore.”

By then Thelma had a more long-term career in mind.

_______________

The thought to investigate a permanent career in the convent came unexpectedly and indirectly through Rosie Kuklinski. The notion gnawed at Thelma, who by then had had six boyfriends “and the same number of proposals.” She discovered a letter Rosie (as Sister Jane Frances) had written home about her happiness at the convent and her regret at not making the commitment to join earlier.

Martha was pleased at her daughter’s decision to enter a religious order. Two of her brothers, Joe and Matt, had daughters in the convent. Joe’s daughter Mary became Sister Mary Alexis and Matt’s daughter Kathleen became Sister Mary Cesarie. (All members of the religious order Sisters of Our Lady of the Missions use Mary as their first name.)

On her mother’s suggestion, Thelma went to see a local Catholic priest while she was still working in Whanganui.

“The first question he asked me was, ‘Does your mother know you are here?’ I said that she was the one who sent me. I went up to the convent on the hill and visited the sisters. I didn’t know anybody in Whanganui so during my time off, I went visiting and talked to the sisters, one from a Polish family.

The superior of that convent, Sister Edna, encouraged Thelma to join their order and the priest suggested the Brigidine Sisters but for Thelma there was only one choice—the same order as that in Inglewood, Stratford and New Plymouth. She knew the Sisters of Our Lady of the Missions (RNDMs).

The future Sister Mary St Martha moved down to Christchurch to start her novitiate training. Doing what she wanted did not stop the inevitable homesickness but for once, she did not return home.

“I shut myself in the bathroom and I cried. I know there were lots of young nuns from the novitiate running around looking for me. I heard them whispering outside but no one knocked on the door… I was just so homesick. I was in that bathroom all afternoon crying, or trying to get my face back into a sociable look.”

“Head office” hit a nerve with Sister St Martha when, 36 years later, it sent out forms for the nuns to list their qualifications and credentials. Her appreciation of her Polish pioneer background and her regard for her family were behind her unorthodox response, based on a quote from Canadian Catholic philosopher Jean Vanier that she had kept for years:

Ask an amateur to do a job and using all he has, he will be eager to succeed. I find that the less academically qualified a person is, the more committed is that person to finding a solution to a particular problem.

Sister St Martha’s love and respect for her ‘unqualified’ parents brothers and sisters came to the fore, especially her father and Gertrude.

“Gert could always find a solution, or make one up. She could turn her hand to anything. Pioneers are like that. My dad didn’t have an engineering degree, but he was quick thinking, could sort out anything on the farm, and could always make a quick buck. The settlers had no qualifications, but they made a living, and they brought up their families.”

This photograph was taken to commemorate Martha and Albert Schimanski’s 50th wedding anniversary.

Sister St Martha’s written response to her superiors was: “I am apprehensive of the highly qualified professional person. In my 36 years of living in close proximity with academically qualified and professional people it is now my firm opinion that the more qualified a person is, the more impersonal is their response to human situations.

“I base my qualifications on 56 years of my personal experience and the wisdom I have acquired from my own personal observations. Therefore with this in mind, I am delighted to present my immediate qualifications as:

- PE–Personal Experience

- LSI–Experience in personal Low Self-Image 1956 to 1969

- PED–Personal experience in depression 1969—1974

- PD–I am qualified in Personal Depression 1974-1975

- QSR–I am qualified in Self Rehabilitation 1977

- SMot–Self-motivated to design and create a programme for women promoting self-esteem and self-worth.

“I was pretty bold sending this down to head office.”

The “SMot” above was a result of an extension course in communication that she took at the University of Waikato. She remembers a seminar she later attended at the same university.

“I loved every minute of it. The tutor was a radical feminist. I wore my habit, black veil and I don’t know how many women came up to me and asked, ‘What are you doing here?’ I said, ‘I’m interested in women and how women live.’ They left me alone. I don’t remember learning anything new there, but it was a great experience. It was a time in religious life when we were allowed to go out on our own.”

Sister St Martha used that freedom to create a course for women with low self-esteem, the spirit of confidence and taught it wherever she was stationed—in Christchurch, Papakura in Auckland, Opunake and Inglewood.

_______________

In the convent, new placements for the sisters were called “puddings.”

“After Christmas everyone anxiously waited for the ‘puddings’ to be given out for the following year. Where were we being moved?”

Sister St Martha had barely finished her novitiate training before she was asked to teach primers in Auckland.

“I was in the sewing room, looking after the linen and making new clothes, new linen and sorting out anything that needed mending. The provincial came to me and said, ‘We’ve got Sister Mary Clotilde up in Ellerslie [Auckland]. She’s got 100 pupils in a new classroom and it’s got a folding door. We need another teacher up there. You can go up and help her teach the primers.’

“I knew nothing about teaching except that I was the babysitter at home looking after all the little ones when they were sent outside.

“I arrived on Sunday and on Monday morning I was sent to the classroom and the concertina doors were closed. I was told to teach this class. The first lesson was Religious Instruction and that would last about an hour. That was easy but what would I do after that?

“I put my ear to the concertina door to hear what Sister was doing on the other side and I thought, ‘Oh yes, I can do that.’ The convent didn’t worry too much about educating their sisters because there was always somebody to help out.”

“… he did start to do something and one day I heard him in the playground telling someone, ‘Sister Martha loves me.’

Twenty years later Sister St Martha asked to enrol at the Catholic teacher’s college at Loretto Hall, Auckland.

“I wasn’t one of their ‘prize’ sisters, but they happened to have a space so the RMDMs could send somebody. I was still doing assignments by correspondence and wanted something more formal.” After two years, she was sent to Hamilton to teach one of two classes of Primmer Fours:

“When I sorted out my class, I found I had children who were very slow, children who were average and children who were very bright, so I had to prepare lessons for three different groups. The teacher next door told me she had one particular boy who she said, ‘could not learn.’ She had him right down the back of the room. She said she taught his sister, who ‘couldn’t learn’ either, and they had another brother at the school, and they were all ‘bad news.’

“I thought, ‘What a terrible way to treat a little child coming to school.’ I said to her, ‘If I give you my very bright children would you give me your very slow ones? Then I’d have just two groups. ‘Oh yes, you can send the bright ones to me,’ she said, so we changed pupils. I had the average, who I didn’t have to worry about very much, and I concentrated on the slow ones.

“I got the boy who was stuck down the back of the room. His name was Gregory. I sat him right at the front and every time I went past him, I poked him in the back and said, ‘I don’t care what you do, but you put something on your page. You’re not giving that book to me without anything on it.’ He used to bring toys to school, and he’d play with these cars, roll them down the desk.

“I said, ‘You—it’s not playtime, it’s worktime. If you’re going to play with that car, I shall pick it up and I shall throw it out of the window—we were in a two-storey building—and I don’t care what happens to it when it gets down on the ground, whether you find it after playtime or somebody else finds it.’

“And he looked at me and I looked at him… He was always in trouble… ‘Sister, Gregory did this,’ and ‘Gregory did that.’

“One day I went up to him and said, ‘Gregory, I love you but I don’t like what you’re doing and I won’t put up with it.’

“I don’t know what happened to that toy. I did throw it out of the window, and he did start to do something and one day I heard him in the playground telling someone, ‘Sister Martha loves me.’ It was just good luck, not good management that I said that.”

Sister St Martha stopped teaching in 1974. She moved to Christchurch in 1979 and on the way there she changed her name by deed poll to Szymanski. She now uses the grammatically correct Polish feminine version, Szymanska. The New Plymouth convent became a Rest Home in 1991, Sister St Martha among the remaining nuns housed in units scattered over several suburbs.

This photograph was taken in 1981 during the 75th Jubilee of St Patrick’s School,

Inglewood.

Back row from left: Sisters Mary St Martha Szymanski, Mary Marcelle Walsh, Mary Bernadine, Patricia Hogan, Mary Eunice, Mary

Helen and Bernadette Fletcher, all teachers.

Front row from left: Sisters Mary Jane Kuklinski, Mary Flora Dwyer, Mary Mercia, also teachers and Catherine Currie, then

Provincial of New Zealand. Next to her are Sisters of Calvery, Mary Alexius (Mary St Martha’s cousin) and Bernadette

O’Neill.

Sister St Martha’s family story shows how quickly the Poles became inter-twined through marriage. Just on her mother’s Drozdowski/Dodunski side, they were already married to married into to the Polish Burkett, Dombrowski, Fabish, Lehrke, Mischewski, Neustrowski, Potroz, Stachurski, Wisniewski and Zimmerman families.

Add a few more family wheels and friendships and it is it is a solid bet that the bonds of those early Polish settlers are not likely to untangle any time soon.

© Barbara Scrivens, 2015

Updated May 2021

ALL PHOTOGRAPHS FROM THE DODUNSKI-SZYMANSKI FAMILY COLLECTION.

THANKS TO THE NORTH AUCKLAND RESEARCH CENTRE IN THE TAKAPUNA LIBRARY FOR THE LOAN OF AUDIO RECORDING EQUIPMENT.

ENDNOTES:

- 1 The christenings index of the Pomeranian Genealogical Association is:

http://www.ptg.gda.pl/index.php/certificate/action/searchB/ - 2 Press, 6 February 1883, page 2, column 1, THE FIRTH OF FORTH, Papers Past, through the National

Library of New Zealand, through a Creative Commons New Zealand BY-NC-SA licence.

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/CHP18830206.2.3.2 - 3 Names and the school photographs gathered by Joyce Cornwall for a 1969 School Jubilee.

- 4 Ibid.

- 5 The Taranaki Herald, 23 August 1876, THE SUNDAY TRAIN QUESTION, page 5, Papers Past,

through the National Library of New Zealand, Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa.

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/TH18760823.2.31

For more on the Fritz Reuter, see:

https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/fritz-reuter/

For more on the first eight Polish families to Taranaki, see:

https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/under-the-mountain/ - 6 For more on the Kuklinski Family story, see:

https://polishhistorynewzealand.org/the-kuklinski-family/