Carol Bungard Meikle

THE CROSS OF HOPE

by Barbara Scrivens

If Carol Bungard Meikle, QSM, had not been wondering about how to celebrate her Baumgardt family’s 140 years in New Zealand, a piece of gnarled wood originating in Poland may have rotted away quietly on the other side of the world.

Instead that piece of robinia (Sorbus aucuparia or in Polish, jarzębina), found on the old family farm in Waihola, was fashioned into mementoes for the 140th anniversary celebrations of Polish settlers to Otago.

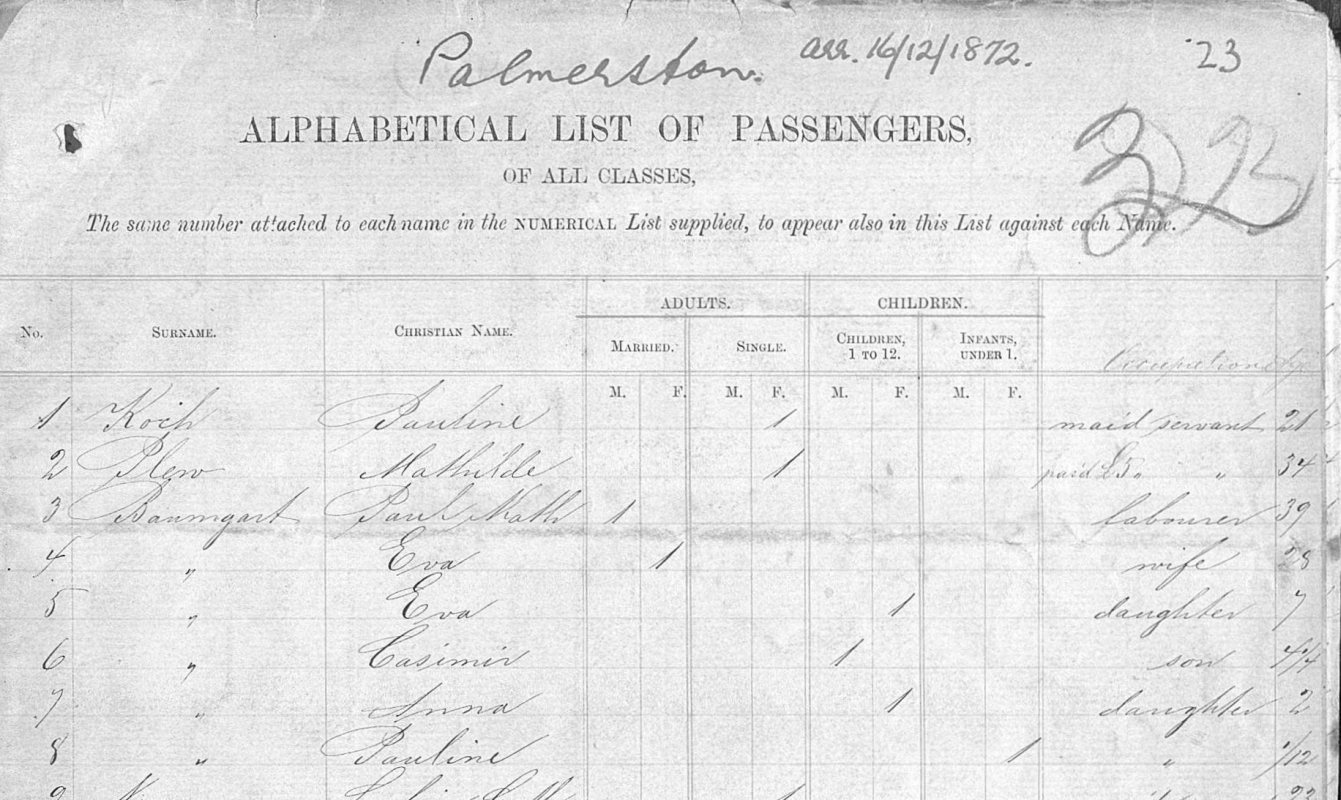

Paul (39) and Eva (28) Baumgardt, with Eva (7), Casimir (4), Anna (2) and baby Pauline, arrived in Port Chalmers with those settlers in December 1872. Casimir was Carol’s grandfather.

Their luggage on the palmerston included some saplings and a few curly bantams, whose offspring apparently still roam Otago paddocks.

Some family stories say those saplings included a cherry; others a robinia. Both were popular in Poland then and are now, the latter as inspiration for romantic songs.1 Other family stories say Paul and Eva carried seeds, easier to protect during a four-month sea voyage to an untested destination.

The Baumgardts’ plan was to buy land and to farm. Within seven months of landing, Paul had bought three three-quarter-acre sections in Waihola for ₤3 each. By 1874, he had added another seven and in 1881 bought a 21-acre farm block on the outskirts of Waihola.2

The family land had fallen out of family hands by the time Carol was inspired to return a piece of the wood to Poland. Familiar with the trees on the property, Carol phoned the new owner to ask whether there was any wood on the farm that could have been planted by her great-grandparents.

“As soon as I asked her whether there was any old wood lying around that could be traced back to the original [relatives], she said, ‘I’ll give you a call back. I know exactly where I’m going to go.’

“She went with her four-wheeler over the hill and dragged out these pieces of wood that had been used for fencing. There was a piece not solid but well grooved with age, beautifully weathered. I had it inspected. It was robinia and that was good enough for me.

Carol designed a cross as a gift for Poland and named it The Cross of Hope. The robinia cross stands on a kauri (Agathis australis ) base, a piece of pounamu (New Zealand greenstone) and Baltic amber was set at its foot. Both the stones and the wood were significant to the joining of the two nations. Shell from paua (an abalone unique to New Zealand’s coastal waters) was set in the cross to represent the 130-day sea voyage made by the Baumgardts and others aboard the palmerston. Carol was satisfied that a circle had been completed.

For the family reunion in Waihola, Paul and Ewa Baumgardt’s descendants launched a family book, wrote a song called The Land We Now Call Home, and made the intricate wreath they laid on Paul and Eva Baumgardt’s graveside, and the red posies they laid on all of Paul’s and Eva’s descendants’ graves in the Waihola cemetery.

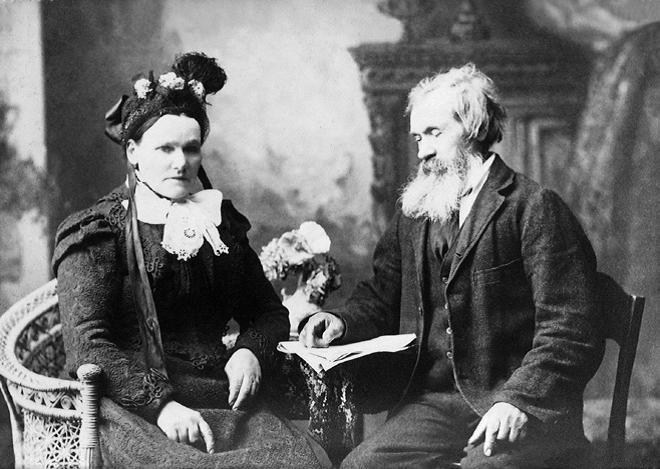

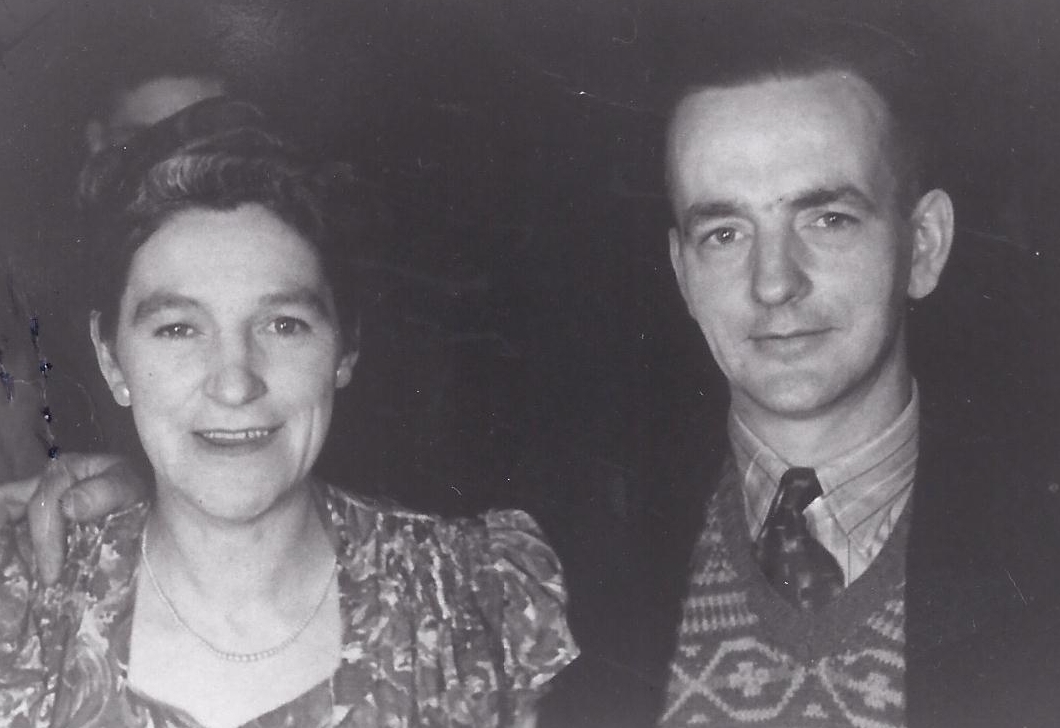

Paul and Eva (née Flis) Baumgardt. This is the image on the front cover of the family book.3

The family book would not have been possible without the curiosity of Carol’s cousin, the late Pauline Morris, and her decades of research. After she died her daughter, Elizabeth Cowie, collated her mother’s work and the photographs and snippets from other family members and had the book ready by 2012.

The Polish Heritage Trust of Otago & Southland (POHOS) hosted a 140th anniversary dinner at the Port Chalmers Town Hall. Guests included the then Polish Ambassador to New Zealand Beata Stoczyńska, who became the first Polish Ambassador to visit Port Chalmers. Ambassador Stoczyńska was accompanied by her husband, the then Polish Consul Sławomir Stoczyński, and the Honorary Consul for the South Island Winsome Dormer.

_______________

“I’m very proud of our historic township and current Port Otago. It’s a very clean, tidy and busy port, conscientious about its balance between growth and the historic precinct. Port Chalmers is a quaint little town, with many historic buildings dating back to those early settlers.”

This and the two photographs below form part of a collection, Old Port Chalmers, by photographer and four-time Port Chalmers mayor between 1899 and 1913, David Alexander De Maus (1847–1925). This is Railway Wharf in 1873, later re-named Bowen Pier after Governor Sir George Bowen.4

The view down George Street, Port Chalmers, to Koputai Bay and the Otago Peninsula, around 1869.5

Port Chalmers’ re-named Bowen Pier 15 months after the Polish settlers arrived in December 1872.6

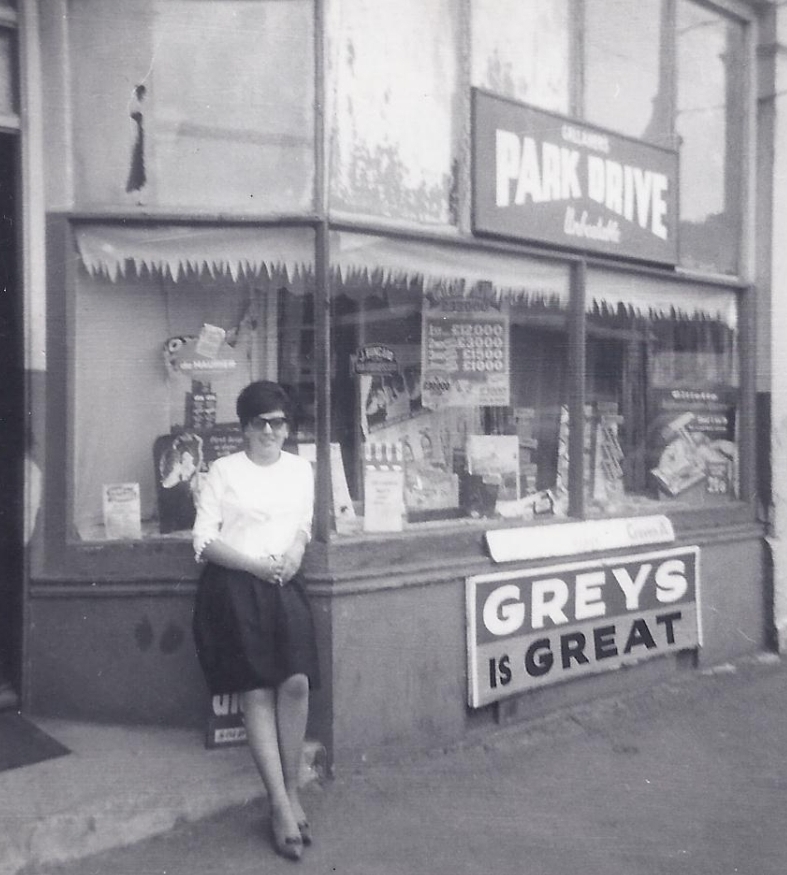

“I’m very passionate about the people of Port Chalmers. I live and breathe for family and the community. My dad, James Bungard, came to Port from Waihola when he was around 20, started up a hairdressing and tobacconist business, married mum and I’ve lived here all my life.”

By the time Carol's grandfather Casimir married Lena Gutschlag in 1892, he had anglicised his name to Joseph Bungard.

James Bungard in his Port Chalmers tobacconist and barber shop circa 1950.

Carol outside her father's shop circa 1964.

“Mum’s grandfather, Henry Flynn, arrived in Port Chalmers in the early 1860s. We think he arrived ahead of his wife, Mary Cowan, whom he married in 1858.”

Jesse William Flynn and Kate Walsh married in 1896. Norah had been their eighth child, the only daughter in a sea-faring family. The responsibility fell on her to look after her aging parents and she lived all her life in the family home that her father bought in Constitution Street the year Norah was born, 1911. Jesse died in 1931, five years before Norah married James Bungard.

James and Norah Bungard on their wedding day. James’ older brother Adam is best man and Edna Reeves is bridesmaid. The girl seated on the left is Kathleen Flynn and the pageboy is Bobby Flynn. If anyone can identify the girl on the right, we would appreciate it.

Left: Faye and Carol circa 1949. Right: Yvonne and Roy Bungard circa 1948. Both photographs were taken at the family home in Constitution Street, Port Chalmers.

Norah and James Bungard, circa 1948.

A Bungard family picnic at Evansdale Glen in January 1949. Norah is holding Carol.

Norah Cecylia Bundard died in childbirth in July 1950. Yvonne, had just turned 13, Roy was 10, Faye had just turned five and Carol was three and a half.

“They buried mum with her baby in her arms. I don’t remember seeing that but Yvonne does.

“My dad never really recovered from mum’s death. He put an ad in the paper for a housekeeper to help with his four children. He got one offer from someone wanting to take one child but Dad didn’t want to split us up. He became so desperate he got on a train and went to see his older sister, Christina (Teanie) Wilson, in Herbert and asked her to let her daughter Chrissie live with us until Yvonne was old enough to take over.

“Chrissie was 17, and she stayed with us for about three years. My grandmother, Kate (Katherine) Flynn, was 82 and struggled to accept that her daughter had died before her. She told me she would see me to school, and she did. I didn’t realise quite how frail she became but she died about six months afterwards.

James Bungard died after a heart attack on 20 March 1978 and is buried at the Port Chalmers cemetery with his wife and their baby. He was still active in his business at the time of his death.

Roy Bungard recently returned to live in Port Chalmers and bought the family home. Carol found out that their old phone number was still available, so arranged to have it transferred to the property.

_______________

Although aware of her Polish roots, growing up and into adulthood Carol felt no reason to pursue that side of her heritage. Until 1989 she led a contented and quiet life caring for her three children, Jamie, Craig and Georgina.

“This was when changes came in throughout New Zealand. Small communities amalgamated into greater cities. I was lying in bed and heard this person saying on the radio, ‘If you’ve got something you can offer your community, put your hand up.’

“I didn’t have a clue about politics but I thought, ‘I love my community, I’ve got a lot to offer.’

“When I went to put my name forward at our then local Borough Council’s office, they said, ‘Oh, no, you’ve got to be nominated.’ I said, ‘I’ll find someone to nominate me.’ That’s how naïve I was at the time.”

In 1989 the Port Chalmers–West Harbour Community electorate voted Carol onto the Dunedin City Council Chalmers Community Board. She quickly absorbed the intricacies involved with local government and “did it all” for the next 12 years.

In 1990 Carol established and successfully operated children’s holiday programmes in the Port Chalmers-West Harbour community and continued to do so for 15 years.

“My partner [Graham Bain] and I opened a shop in Port Chalmers in 1985. One day a young mother was chatting to me in the shop and said, ‘Carol, you should start a foodbank up in Port Chalmers, because when I need to go into Dunedin for help, it costs me $2.50 each way. That is a loaf of bread for me and my family.’

“As I was planning to set up the foodbank at the back of our business premises, a staff member from the Dunedin City Council said to me, ‘Carol, are you sure this will work—jewellery, crafts and a foodbank?’ I said, ‘And why not? I can give somebody a food parcel just as well as I can take a request for having a customer’s jewellery fixed, no trouble.’

“One thing I did learn was that those people were genuine. They didn’t see the jewellery; they weren’t even tempted. They were just naïve and grateful for getting what was needed for the day.

“Back then I could look after the shop and run the foodbank and a support and information centre. I was just an advocate of the people— that Polish thing that makes you fight for the rights of others—but after 15 years I needed to make changes. I was worn out. I’d run myself down to the ground and I struggled. The holiday programme wasn’t an issue, but I struggled to divorce myself from the hurts and the suffering.”

A conversation with a fellow Community Board member changed Carol’s direction in life. He questioned why Carol, who represented her community in so many things, did not represent her own culture.

“I knew there was a Polish group established in Dunedin but up to then, I didn’t have the time to join. After my friend’s challenge, I thought I had better go and show an interest in a Polish function at the Otago Settlers Museum. POHOS had put together a display.

“I saw a beautiful painting of the ship otago by Margaret Anne Howard. I recognized the landscape in the painting. I said to the artist, ‘That looks like Otago Harbour.’ Then I looked around and saw photos of my family and thought to myself, ‘Carol you should be very proud of your family.’

“One thing led to another and with pride I went on to become a Trust Member of the Polish society. The timing was good—at the time I was Vice Chair for the Dunedin City Council Chalmers Community Board. After 12 years I decided to stand down from politics.”

Carol, second from left, after receiving her QSM from New Zealand Governor-General, the Right Honourable Sir Anand Satyanand, GNZM, QSO. His wife, Lady Susan Satyanand, is to the right of him. Carol’s partner, Graham Bain, is on the far left and her daughter, Georgina Smith (née Meikle), on the far right.

_______________

Paul and Eva Baumgardt were both born in Gołczewo (near Bytów) in then Prussian-occupied north-western Poland, Paul in 1833 and Eva (née Flis) in 1844. Their eldest son, Johann, died in 1868 aged two.

Parish records show Paul’s father’s name was originally Bongarda,7 and his own Christian name originally Paweł Maciej.8 His changed name confirms the forced germanisation of Poles living under Bismarck. Eva would be spelt in Polish as Ewa. (For a more in-depth explanation, see polish anchors 1872–1876.)

There seems to be no specific catalyst for the family’s immigration to New Zealand but the timing coincides with mass emigration out of the region at the time. Carol believes her great-grandparents were following their dreams. The palmerston left Hamburg five days after the may queen left Gravesend, yet the may queen arrived in Port Chalmers on 24 October while the passengers of the palmerston endured a further 38 days at sea.

Dane Christen Christensen’s diary of the voyage explains why the journey took so long. The ship, with 287 listed passengers, entered the North Sea on 1 August “in heavy storm nearly everybody seasick…” 9 On 4 August a strong head wind “drove the ship backwards for a good number of miles, which nearly brought the ship on the Cliffs of Heligoland.” It finally left the English Channel “in fine weather and fair wind from the North.”10

By 16 September the palmerston languished in the “middle center [sic] between the North and South Poles.” Mr Christensen, father of four, had documented 10 deaths, including his own daughter (20-month-old Annabel), a stillbirth, seven children and a Norwegian widower who was accidentally poisoned during the weekly fumigation of the quarters below deck.

“… our passage across that Godforsaken part of our travel lasted almost for three weeks… scarcely a breath of wind and in consequence thereof did the rigging of ropes and tackle stretch and constantly slack and therewith make an intolerable noise to such an extent that it seemed that the whole rigmarole would break down, and so did the topyard on the main mast. It was brought on deck in two pieces in the awful rolling of the ship on account of the heavy seas. But the worst of all was that our water tanks were almost empty at these times and the little which was left got rotten of the abominable heat and was churned backward and forward in the tanks. Then there was the rust from the old iron chains, so a good dose of vinegar was put down in the few buckets of water so as to take the bad taste of rust, for all that it was a horrible drink. It made even coffee or tea smell and tasted rotten. A lot of people could be seen after drinking to spit and cough for to cleanse their mouth…

“… it started with a down pour of rain like it came from a sluice gate. Men and boys undressed themselves and laid down on the deck for a warm bath and drank rain water till they were nearly bursting. Canvas was spread in the lower rigging so as to catch the rain water for the tanks.”

By 2 October, as the palmerston rounded the Cape of Good Hope, gales smashed heavy waves against, and into, the vessel and snow forced the Christensen family to “take to our woollen garments and underwear.”

Mr Christensen wrote one of his longest entries on 13 November, after an 18-month-old Polish boy’s death, the 15th of the journey, coincided with the captain’s birthday. Men received brandy, women wine and each child a packet of currants and prunes. “And afterwards dancing and some sing song” at one end of the married passengers’ quarters while the “corpse of a boy was laying ready to be sent to the bottom of the Pacific Ocean.”

“Our Quarter… is midship about 130 feet long and the full width of the ship, 40 ft. …the interior of that Compartment… serves for bedrooms, dining room, sitting room, tea room… dressing room also and in bad weather as laundry… The seats along the tables, for we have no chairs, are top heavy and cannot stand by themselves when they are not lashed by weight of occupation when heavy seas are running and that is almost every day and night.

“… worst of all in extra bad weather the Gangway from below on to the deck is always blocked by fastening the hatches over the sternway to prevent the seawater and heavy rain to come down… We are all as one in our unhappiness and painful surrounds.

“… It cannot be wondered that so many unlucky children have to go overboard…”

The captain, German Peter Köhn, “in a dense dark spell,” steered the fully rigged ship “within a few feet of a towering cliff.” The next morning Köhn apparently blamed the sea chart for not marking the land. It is not clear where that incident happened but the diary marked the date as 29 November.

Six days later, “Great joy on board as we can see New Zealand… no wind to bring the ship forward.

“Here is beautiful forest on both sides of the Harbour where the birds are singing and cattle on grass amongst the trees. We have received provisions from Dunedin consisting of fresh white bread, milk, bacon, vegetables also… good fresh water.”11

Official records use 16 December as the arrival date. Mr Christensen said on 6 December that they had seen a steamer that would take them into Port Chalmers harbour. On 16 December two families with a sick child left the ship for a quarantine island. As much as the 18-day wait for quarantine clearance would have been frustrating, Paul Baumgardt, whose family reported him as being extremely seasick on the journey, must have been relieved to be in the harbour’s shelter.

Because of the number of deaths from scarlatina and typhoid fever, the ship was quarantined until Christmas Eve, when the passengers left for the Dunedin immigration barracks.

_______________

The palmerston’s single men and women were “easily disposed of” but Dunedin immigration officer Colin Allan reported to the Under Secretary for the Immigration Office in Wellington that the new colony’s “farmers and runholders are generally disinclined to employ men with a family of children… and much more so [when] they were entirely ignorant of the English language.”

The Clutha railway proved a blessing for those without English: Messrs Brogen and Co. employed “some sixty of the German [sic] immigrants by the Palmerston,” The evening star announced in Dunedin on 13 January 1873.

Officer Allan brokered the agreement, arranged for the families’ transport 25 kilometres south of Dunedin and bought timber to make tents for them:

“In incurring these expenses without authority, I hope the Government will give me credit for doing what I thought to be for the best in the circumstances, and more advantageous than having a number of men, women and children maintained in barracks at the public expense.”12

The railway work gave the Poles the start they needed. As soon as they were able, they started buying land in nearby Greytown (re-named Allanton) and Waihola. Newspapers regularly reported on those who bought sections, including Paul Baumgardt and other palmerston Poles.

According to family story, Paul built the first family house of timber and canvas near where the St Hyacinth church once stood on Nore Street. An early map in the Baumgardt book shows the family owned the five sections immediately adjacent to the church and eight others in the town basin.

Paul later moved his family up the hill to Beacon Street where he established an orchard, kept cows, pigs and goats, and enjoyed eggs from the hens he brought from Poland.

Eva, “a kind person,” apparently enjoyed milking the cows on the roadside outside their home.13

Paul and Eva had six more children in New Zealand: August Michael (1874-1951), Mary Maud (1876-1946), Franz (1877-1950), Rosa (1880-1952), Julia (1882-1962) and Eva Martha (1886-1896).

Eva Baumgardt died in 1908. Joseph and Lena Bungard looked after Paul until his death in 1923.

Baumgardt/Bungard families occupy much of the top of the Waihola cemetery, overlooking the township and lake and on the same road where Paul and Eva farmed. Their grave is in the foreground. They share it with their youngest child, Eva, who died aged nine in 1896.

_______________

Joseph and Lena Bungard married in Milton. As well as Joseph’s changed name, their marriage certificate records Lena’s as Domen, an incorrect spelling of her mother’s maiden name, Dauman.

Lena Bungard told Carol’s brother, Roy, why she used her mother’s name instead of her father’s:

Lena’s full name was Caroline Wilhelmina. (Carol was named after her.) She was born on Christmas Day 1873, a day before the scimitar left London with her parents, Wilhelm Gutschlag (27) and Caroline Dauman (20). Their baby does not seem to appear on the scimitar passenger list.

In New Zealand Lena’s father found work on the railway line through the Taieri valley south of Dunedin. The new family lived in one of the tents erected for them in the scrub behind Mr McKegg’s White Horse Hotel. Three other married German couples and two single German men lived in the same camp.

One night, when Lena was eight months old, a can of lit charcoal—used to heat the tent—exploded. Wilhelm escaped with “his hair in absolute flames” but Caroline “suffered injuries of a terrible nature” and baby Lena was “badly burned about the head.”14 The new mother Caroline died of her injuries. The family book says that a childless German couple, Carl and Louisa Hagen, cared for Lena.

Wilhelm, who became known as William, continued to work for the railways and married Mary “Dovolosky” in 1881.15 They had 12 children.

At some stage Lena returned to live with her father and his second family in Gore but left again after William found out about her plans to marry and refused to speak to her. This was when Lena started to use her mother’s maiden name.

Lena Bungard, born Caroline Wilhelmina Gutschlag.

Lena told Roy that William Gutschlag did soften and resumed contact after her first child was born.

The Joseph Bungards lived out their lives in Waihola. They had 12 children: Julius, Lily, Andrew, Peter, Eva, Eric, William, Adam (Pauline Morris’s father), Christina, David, James (Carol’s father) and Ellen.

Joseph Bungard on his Lake View Road, Waihola, property circa 1898. His second son, Andrew, born in 1896, sits on top of the haystack. Joseph named his oxen Roly and Poly.

An unnamed passing photographer from the otago daily times around 1910 captured several shots of Joseph ploughing his land. The photographs were included in a Christmas edition and are now held at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa.

The Bungard's first home was a modest cottage near Lake Waihola. They later bought another property where Joseph farmed with his father. The growing family moved in with Paul and Eva in 1900, the same year their fifth child, Eva junior, was born. After Eva senior died in 1908 Joseph took over the running of his parents’ farm and acquired adjacent land from Bernard Wisnesky. By 1932 Joseph had 88 acres. He also worked as a labourer and at one stage was sexton for the Waihola cemetery.

Lena, a keen rabbiter, ran the farm. Her family said she enjoyed tatting by candlelight in front of the fire and played host to many visiting relations during the holidays. Joseph died on 6 May 1938, aged 70, and Lena on 26 November 1962, aged 88.

Lena and her children at Joseph’s funeral. Back from left: Julius, Andrew, Peter, Eric, Bill and Adam. Front row from left: David, Lily, Lena, Teanie and James. The family’s youngest child, Ellen, was absent.

_______________

These days, Carol takes pleasure in watching the cruise ships coming up the Otago Harbour—she has a perfect view from her home overlooking Deborah Bay—and the new advocacy role she had created for herself, greeting Polish visitors.

“I often think how excited the Polish settlers must have been sailing up the Otago harbour that first time.

“Our shop is just a few hundred metres from the dock. I can’t speak one word of Polish but I can pick it out when a Polish person comes into the shop.

“I say to them that I am a descendant of the first Polish people to Otago and tell them, ‘Where your ship is berthed is where the first Polish people arrived here in 1872.’ I show them the baumgardt family history book that I keep on hand, where there are maps and Polish words that they recognise.

“It’s personal, and immediately there’s a bond between us. Those Poles might see and buy lots of beautiful things here, but to give them something personal and point out a name, well, it may be their only experience of other Poles in this country.

“They have no problems following me and they depart Port Chalmers richer for the Polish connections they experienced here.”

_______________

Paul and Eva’s immediate family:

- Eva Augustina (8 March 1864–31 August 1890): Also known as Effie or Christina. She worked as a housemaid in Waihola. Christiana “Bunguart” married John “Clucoeski” (John Thomas Klukowski), labourer of Waikaka. She died aged 25 and is buried at the Gore cemetery under the name Christina Klukosky.

- Casimir Joseph (4 March 1868–6 May 1938): His name in Polish would have been Kazimierz Józef Bongarda. His New Zealand nickname, Midnight Joe, apparently came about because, although he disliked the mornings, he worked late into the night.

- Anna Katharina (2 May 1870–10 June 1917): Known as Annie. She moved to Melbourne in 1892 and married Antonio Francisco there.

- Paulina Julianna (16 June 1872–14 March 1912): Known as Fanny. Fanny “Baugat” (also spelt Bangat) married John Wells in 1896. The Wells had 10 children, David, Frances, Frederica, Annie, Mary, Ivy, Margaret, James, Winnie and Ada, who was three months old when her mother died. Fanny is buried at Kaitangata cemetery, Otago.

- August Michael (4 September 1874–4 May 1951: First Baumgardt birth in New Zealand, in Waihola. He married Maggie Hynes in 1896. They share a burial plot in Andersons Bay cemetery under the names Augustus and Margaret Baumgardt.

- Mary Maud (24 June 1876–18 February 1946): Born in Waihola, she married Alexander Morrison in 1895. She had David from an earlier relationship, and together they had Annie, Herbert, Olive, Gladys and Oswald. Mary died in Kaitangata and is buried there with her husband.

- Franz (13 July 1878–1950): Known as Frank. As Frank Baumgardt, he married Lillias Porteous Macdonald Mason in 1904. Frank was an engine driver, mechanical engineer, flax cutter, trapper and shearer. He and Lillias share a burial plot at the Southern cemetery in Dunedin.

- Rosa (1 August 1880–1 April 1952): She was born in Waihola and followed her sister Annie to Australia. She married George Dickson Vardy and died in Adelaide.

- Julia (12 October 1882–11 August 1962): Sometimes known as Bridget, she married David Wilson in 1900 as “Bangat.” They had 15 children, Olive, David, James, Leslie, Mary, Emily, Vera, Mona, Olga, Laura, John, Gladys, Herbert, Olive and Maida. Julia and David are buried together at Andersons Bay cemetery.

- Eva Martha (1886–27 October 1896): She died in Waihola aged nine and is buried with her parents.

© Barbara Scrivens, 2018.

FAMILY PHOTOGRAPHS COURTESY ELIZABETH COWIE AND THE BAUMGARDT FAMILY HISTORY COLLECTION, THE CROSS OF HOPE MONTAGE FROM CAROL MEIKLE, THE POSTCARD IMAGES FROM THE PORT CHALMERS MUSEUM AND OTHER IMAGES BY BARBARA SCRIVENS.

THANKS TO:

THE POLISH EMBASSY IN NEW ZEALAND FOR TRAVEL AND ACCOMMODATION EXPENSES IN DUNEDIN.

THE NORTH AUCKLAND RESEARCH CENTRE IN THE TAKAPUNA LIBRARY FOR THE LOAN OF AUDIO RECORDING EQUIPMENT.

ENDNOTES:

- 1 - An internet search with the words “jarzebina,” “czerwona” (red) and “piosenka” (song) yields many musical results.

- 2 - Return of the Freeholders of New Zealand, October 1872… giving the names,

addresses and occupations of owners of land, compiled from assessment rolls of the Property Tax department. The roll

mis-spelt Paul’s name as Bungardt.

A CD of the roll is available from the New Zealand Society of Genealogists,

https://www.genealogy.org.nz/ - 3 - Baumgardt Family History, complied by Elizabeth Cowie, AM Publishing, New

Zealand,

ISBN: 978-0-473-20799-1. - 4 - Postcards bought from the Regional Museum, Beach Street, Port Chalmers.

www.pcmuseum.co.nz - 5 - Ibid.

- 6 - Ibid.

- 7 - From the Poles Down South website:

https://polesdownsouth.wordpress.com/in-new-zealand/early-polish-settlers/annis-family/a-d/baumgardt-family/ - 8 - https://www.geni.com/people/Paul-Baumgardt/6000000021595136364

- 9 - Several copies of the Christen Christensen’s translated diary appear on the internet. This

one from:

http://quarantineisland.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/The-Voyage-of-The-Palmerston-1872.pdf - 10 - Ibid.

- 11 - This and all the quotes above from Christen Christensen’s diary.

- 12 - Appendix to the Journals of the House of Representatives (AJHR), 1873 Session I, D-01, IMMIGRATION TO NEW ZEALAND. MEMORANDA TO THE AGENT-GENERAL, page 49, enclosure 1, no. 52.

- 13 - Ibid Poles Down South website.

- 14 - Bruce Herald, 28 August 1874, page 5, Papers Past through the

National Library of New Zealand,

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/BH18740828.2.20 - 15 - From New Zealand Internal Affairs Department's on-line births, deaths and marriage

records

https://www.bdmhistoricalrecords.dia.govt.nz